Chapter 9: The Ranges Library

The previous chapter was dedicated to understanding the three main pillars of the standard library: containers, iterators, and algorithms. Throughout that chapter, we used the abstract concept of range to represent a sequence of elements delimited by two iterators. The C++20 standard makes it easier to work with ranges by providing a ranges library, consisting of two main parts: on one hand, types that define non-owning ranges and adaptations of ranges, and on the other hand, algorithms that work with these range types and do not require iterators to define a range of elements.

In this final chapter, we will address the following topics:

- Moving from abstract ranges to the ranges library

- Understanding range concepts and views

- Understanding the constrained algorithms

- Writing your own range adaptor

By the end of this chapter, you will have a good understanding of the content of the ranges library and you will be able to write your own range adaptor.

Let’s begin the chapter with a transition from the abstract concept of a range to the C++20 ranges library.

Advancing from abstract ranges to the ranges library

We have used the term range many times in the previous chapter. A range is an abstraction of a sequence of elements, delimited by two iterators (one to the first element of the sequence, and one to the one-past-the-last element). Containers such as std::vector, std::list, and std::map are concrete implementations of the range abstraction. They have ownership of the elements and they are implemented using various data structures, such as arrays, linked-lists, or trees. The standard algorithms are generic. They are container-agnostic. They know nothing about std::vector, std::list, or std::map. They handle range abstractions with the help of iterators. However, this has a shortcoming: we always need to retrieve a beginning and end iterator from a container. Here are some examples:

// sorts a vector

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 4 };

std::sort(v.begin(), v.end());

// counts even numbers in an array

std::array<int, 5> a{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 4 };

auto even = std::count_if(

a.begin(), a.end(),

[](int const n) {return n % 2 == 0; });There are few cases when you need to process only a part of the container’s elements. In the vast majority of cases, you just have to write v.begin() and v.end() over and over again. This includes variations such as calls to cbegin()/cend(), rbegin()/rend(), or the stand-alone functions std::begin()/std::end(), and so on. Ideally, we would prefer to shorten all this and be able to write the following:

// sorts a vector

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 4 };

sort(v);

// counts even numbers in an array

std::array<int, 5> a{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 4 };

auto even = std::count_if(

a,

[](int const n) {return n % 2 == 0; });On the other hand, we often need to compose operations. Most of the time that involves many operations and code that is too verbose even when using standard algorithms. Let’s consider the following example: given a sequence of integers, we want to print to the console the square of all even numbers, except the first two, in descending order of their value (not their position in the sequence). There are multiple ways to solve the problem. The following is a possible solution:

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 8, 7, 6, 4 };

// copy only the even elements

std::vector<int> temp;

std::copy_if(v.begin(), v.end(),

std::back_inserter(temp),

[](int const n) {return n % 2 == 0; });

// sort the sequence

std::sort(temp.begin(), temp.end(),

[](int const a, int const b) {return a > b; });

// remove the first two

temp.erase(temp.begin() + temp.size() - 2, temp.end());

// transform the elements

std::transform(temp.begin(), temp.end(),

temp.begin(),

[](int const n) {return n * n; });

// print each element

std::for_each(temp.begin(), temp.end(),

[](int const n) {std::cout << n << '

'; });I believe most people would agree that, although anyone familiar with the standard algorithms can easily read this code, it’s still a lot to write. It also requires a temporary container and repetitive calls to begin/end. Therefore, I also expect most people would more easily understand the following version of the previous code, and probably prefer to write it as such:

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 8, 7, 6, 4 };

sort(v);

auto r = v

| filter([](int const n) {return n % 2 == 0; })

| drop(2)

| reverse

| transform([](int const n) {return n * n; });

for_each(r, [](int const n) {std::cout << n << '

'; });This is what the C++20 standard provides with the help of the ranges library. This has two main components:

- Views or range adaptors, which represent non-owning iterable sequences. They enable us to compose operations more easily such as in the last example.

- Constrained algorithms, which enable us to operate on concrete ranges (standard containers or ranges) and not on abstract ranges delimited with a pair of iterators (although that’s possible too).

We will explore these two offerings of the ranges library in the next sections, and we will begin with ranges.

Understanding range concepts and views

The term range refers to an abstraction that defines a sequence of elements bounded by start and end iterators. A range, therefore, represents an iterable sequence of elements. However, such a sequence can be defined in several ways:

- With a begin iterator and an end sentinel. Such a sequence is iterated from the beginning to the end. A sentinel is an object that indicates the end of the sequence. It can have the same type as the iterator type or it can be of a different type.

- With a start object and a size (number of elements), representing a so-called counted sequence. Such a sequence is iterated N times (where N represents the size) from the start.

- With a start and a predicate, representing a so-called conditionally terminated sequence. Such a sequence is iterated from the start until the predicate returns false.

- With only a start value, representing a so-called unbounded sequence. Such a sequence can be iterated indefinitely.

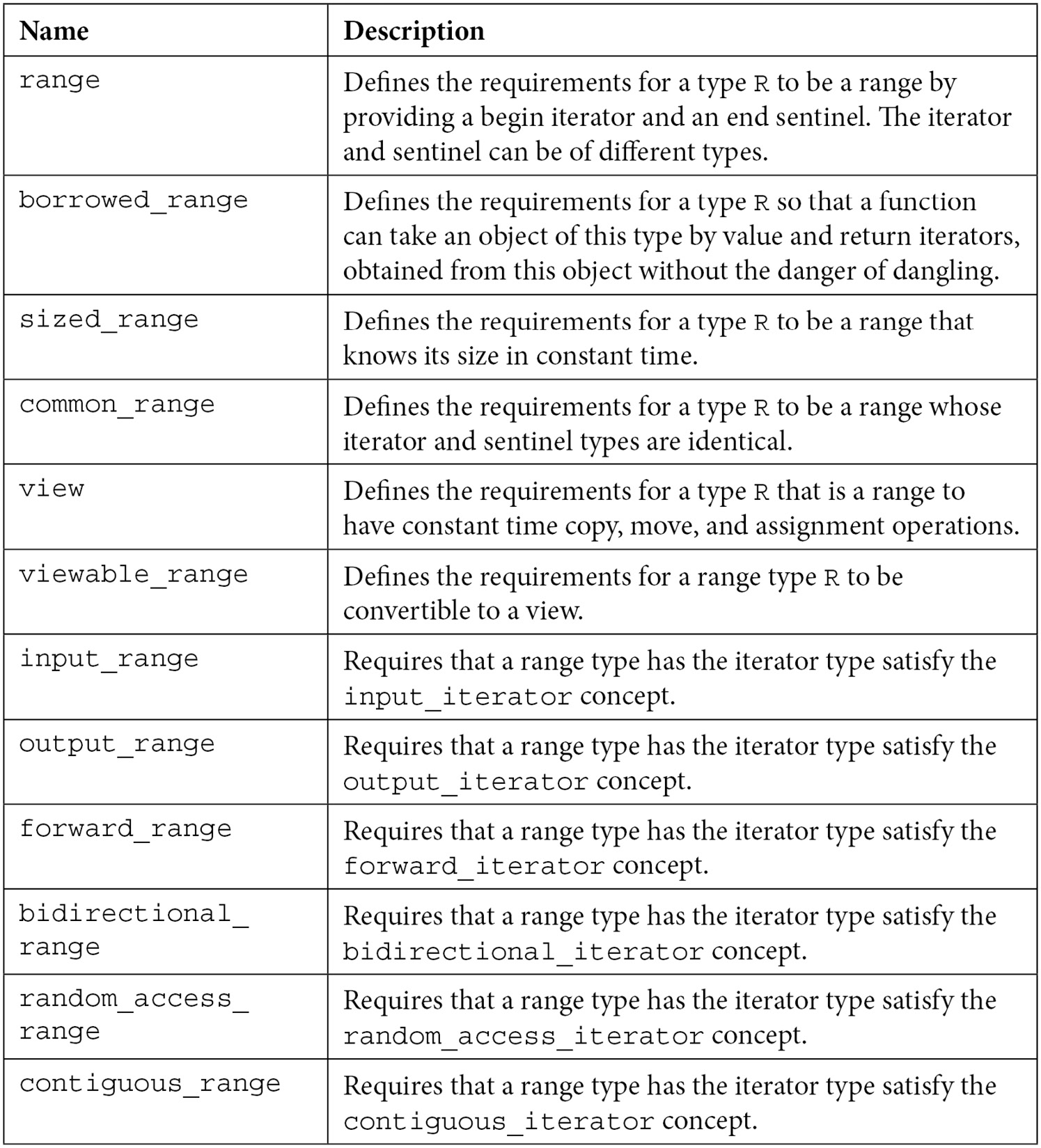

All these kinds of iterable sequences are considered ranges. Because a range is an abstraction, the C++20 library defines a series of concepts to describe requirements for range types. These are available in the <ranges> header and the std::ranges namespace. The following table presents the list of range concepts:

Table 9.1

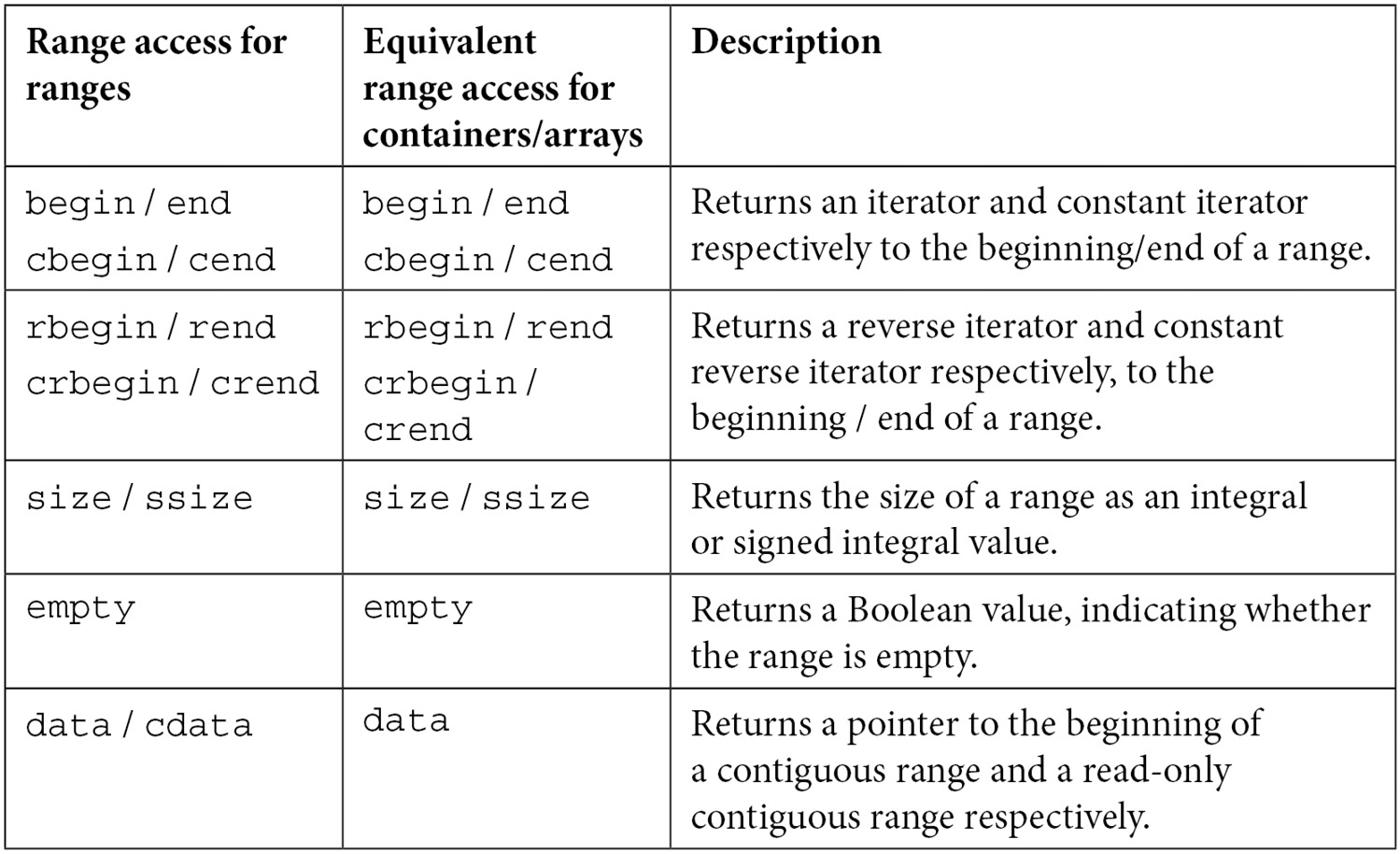

The standard library defines a series of access functions for containers and arrays. These include std::begin and std::end instead of member functions begin and end, std::size instead of member function size, and so on. These are called range access functions. Similarly, the ranges library defines a set of range access functions. These are designed for ranges and are available in the <ranges> and <iterator> headers and the std::ranges namespace. They are listed in the next table:

Table 9.2

The use of some of these functions is demonstrated in the following snippet:

std::vector<int> v{ 8, 5, 3, 2, 4, 7, 6, 1 };

auto r = std::views::iota(1, 10);

std::cout << "size(v)=" << std::ranges::size(v) << '

';

std::cout << "size(r)=" << std::ranges::size(r) << '

';

std::cout << "empty(v)=" << std::ranges::empty(v) << '

';

std::cout << "empty(r)=" << std::ranges::empty(r) << '

';

std::cout << "first(v)=" << *std::ranges::begin(v) << '

';

std::cout << "first(r)=" << *std::ranges::begin(r) << '

';

std::cout << "rbegin(v)=" << *std::ranges::rbegin(v)

<< '

';

std::cout << "rbegin(r)=" << *std::ranges::rbegin(r)

<< '

';

std::cout << "data(v)=" << *std::ranges::data(v) << '

'; In this snippet, we used a type called std::views::iota. As the namespace implies, this is a view. A view is a range with additional restrictions. Views are lightweight objects with non-owning semantics. They present a view of an underlying sequence of elements (a range) in a way that does not require copying or mutating the sequence. The key feature is lazy evaluation. That means that regardless of the transformation they apply, they perform it only when an element is requested (iterated) and not when the view is created.

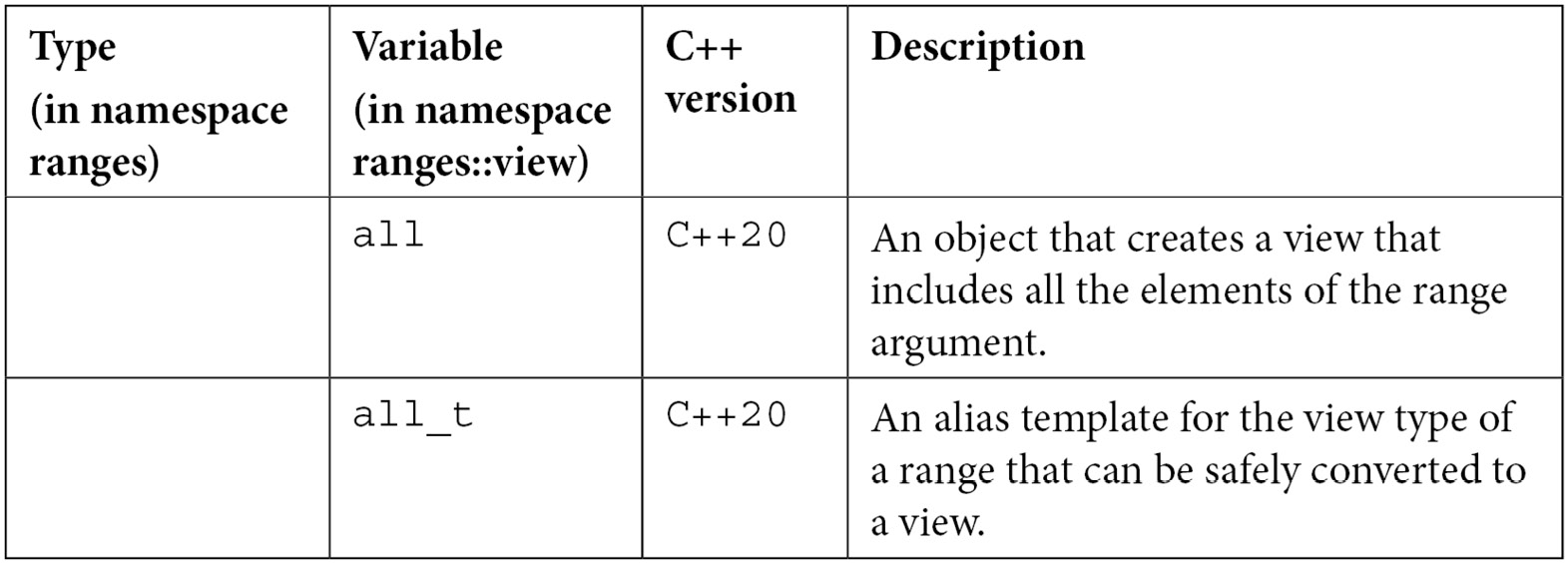

There is a series of views provided with C++20, and new views have been also included in C++23. Views are available in the <ranges> header and std::ranges namespace in the form, std::ranges::abc_view, such as std::ranges::iota_view. However, for convenience of use, in the std::views namespace, a variable template of the form, std::views::abc, such as std::views::iota, also exists. This is what we saw in the previous example. Here are two equivalent examples for using iota:

// using the iota_view type for (auto i : std::ranges::iota_view(1, 10)) std::cout << i << ' '; // using the iota variable template for (auto i : std::views::iota(1, 10)) std::cout << i << ' ';

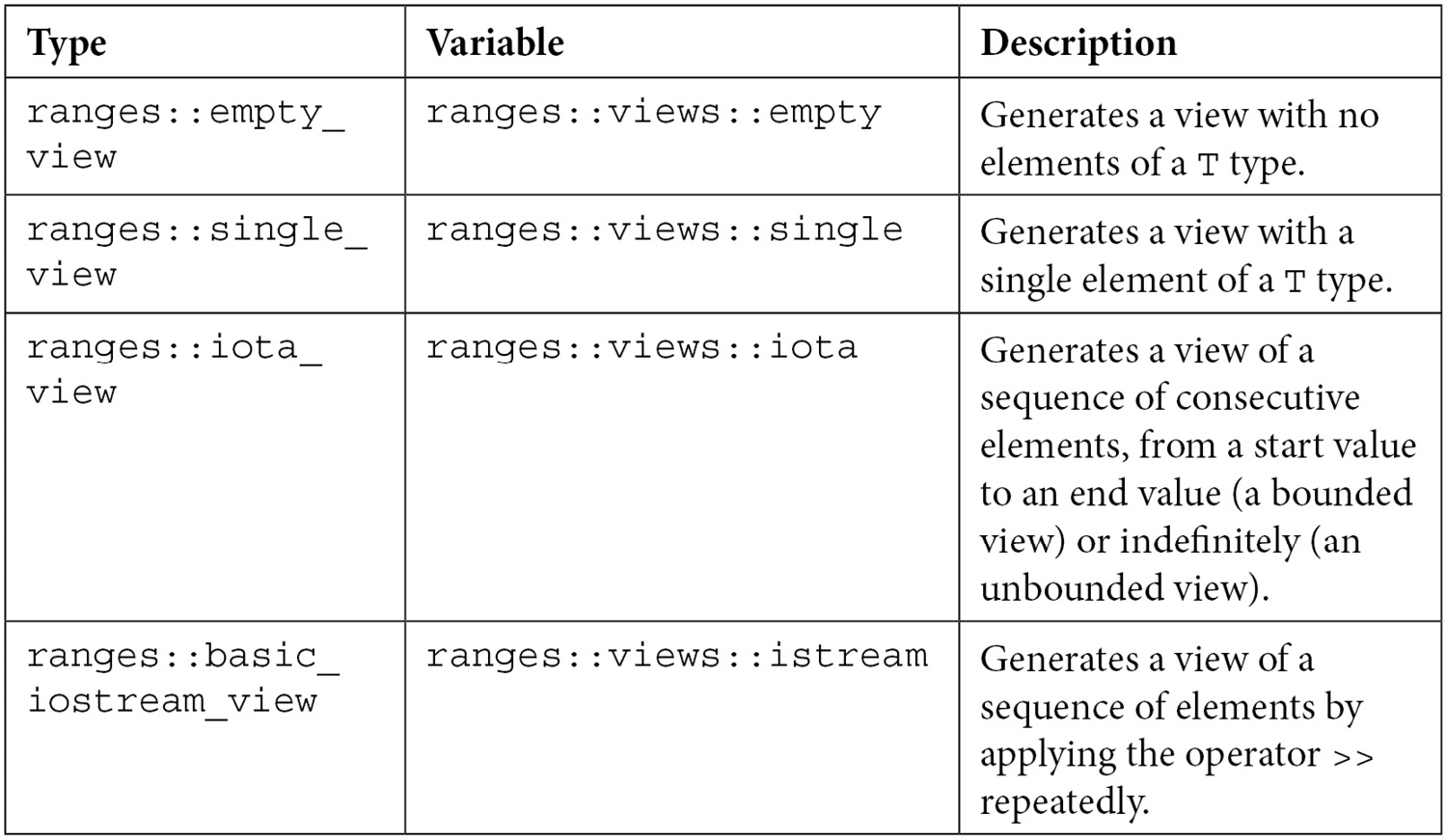

The iota view is part of a special category of views called factories. These factories are views over newly generated ranges. The following factories are available in the ranges library:

Table 9.3

If you are wondering why empty_view and single_view are useful, the answer should not be hard to find. These are useful in template code that handles ranges where empty ranges or ranges with one element are valid inputs. You don’t want multiple overloads of a function template for handling these special cases; instead, you can pass an empty_view or single_view range. The following snippets show several examples of using these factories. These snippets should be self-explanatory:

constexpr std::ranges::empty_view<int> ev;

static_assert(std::ranges::empty(ev));

static_assert(std::ranges::size(ev) == 0);

static_assert(std::ranges::data(ev) == nullptr);

constexpr std::ranges::single_view<int> sv{42};

static_assert(!std::ranges::empty(sv));

static_assert(std::ranges::size(sv) == 1);

static_assert(*std::ranges::data(sv) == 42);For iota_view, we have already seen a couple of examples with a bounded view. The next snippet shows again an example not only using a bounded view generated with iota but also an unbounded view, also generated with iota:

auto v1 = std::ranges::views::iota(1, 10);

std::ranges::for_each(

v1,

[](int const n) {std::cout << n << '

'; });

auto v2 = std::ranges::views::iota(1) |

std::ranges::views::take(9);

std::ranges::for_each(

v2,

[](int const n) {std::cout << n << '

'; });This last example utilizes another view called take_view. This produces a view of the first N elements (in our example, 9) of another view (in our case, the unbounded view produced with iota). We will discuss more about this shortly. But first, let’s take an example using the fourth view factory, basic_iostream_view. Let’s consider we have a list of article prices in a text, separated by a space. We need to print the total sum of these prices. There are different ways to solve it, but a possible solution is given here:

auto text = "19.99 7.50 49.19 20 12.34";

auto stream = std::istringstream{ text };

std::vector<double> prices;

double price;

while (stream >> price)

{

prices.push_back(price);

}

auto total = std::accumulate(prices.begin(), prices.end(),

0.0);

std::cout << std::format("total: {}

", total);The highlighted part can be replaced with the following two lines of code that use basic_iostream_view or, more precisely, the istream_view alias template:

for (double const price :

std::ranges::istream_view<double>(stream))

{

prices.push_back(price);

}What the istream_view range factory is doing is applying the operator >> repeatedly on the istringstream object and producing a value each time it is applied. You cannot specify a delimiter; it only works with whitespaces. If you prefer to use standard algorithms rather than handcrafted loops, you can use the ranges::for_each constrained algorithm to produce the same result, as follows:

std::ranges::for_each(

std::ranges::istream_view<double>(stream),

[&prices](double const price) {

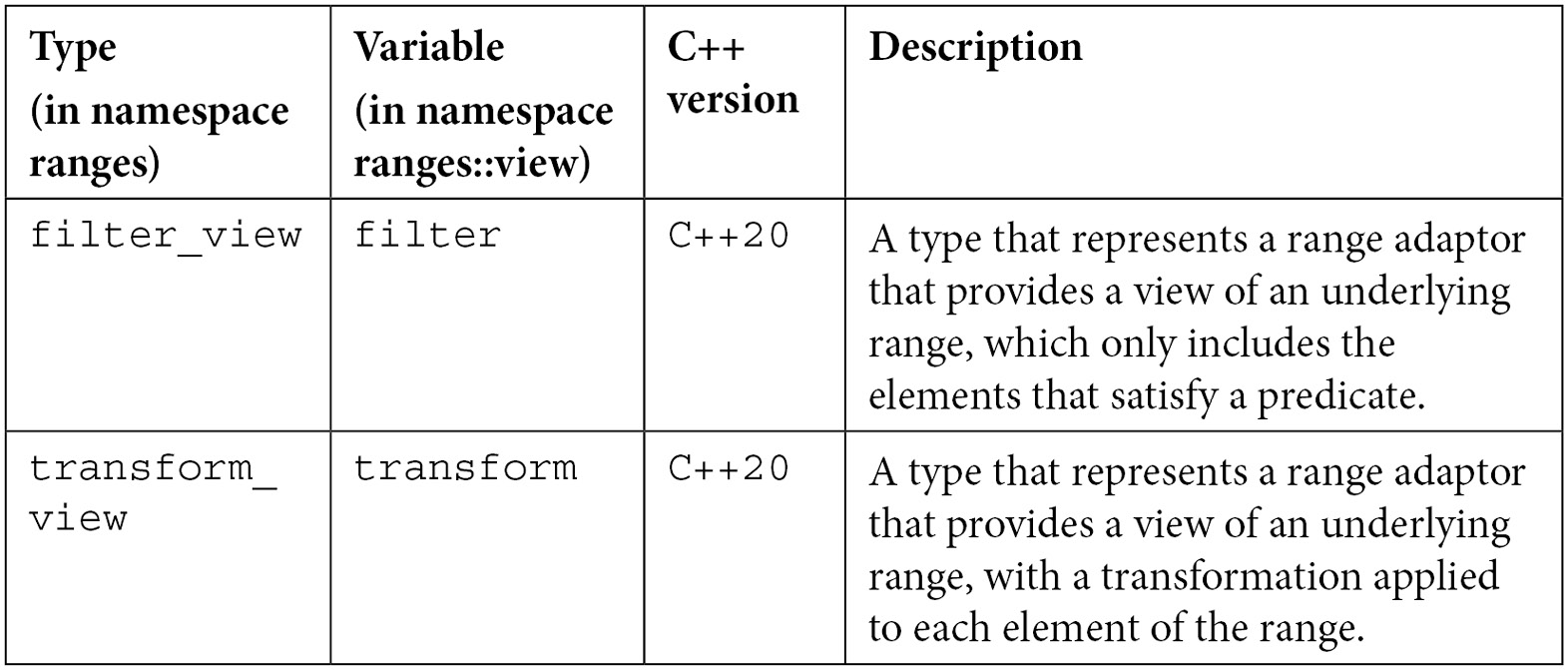

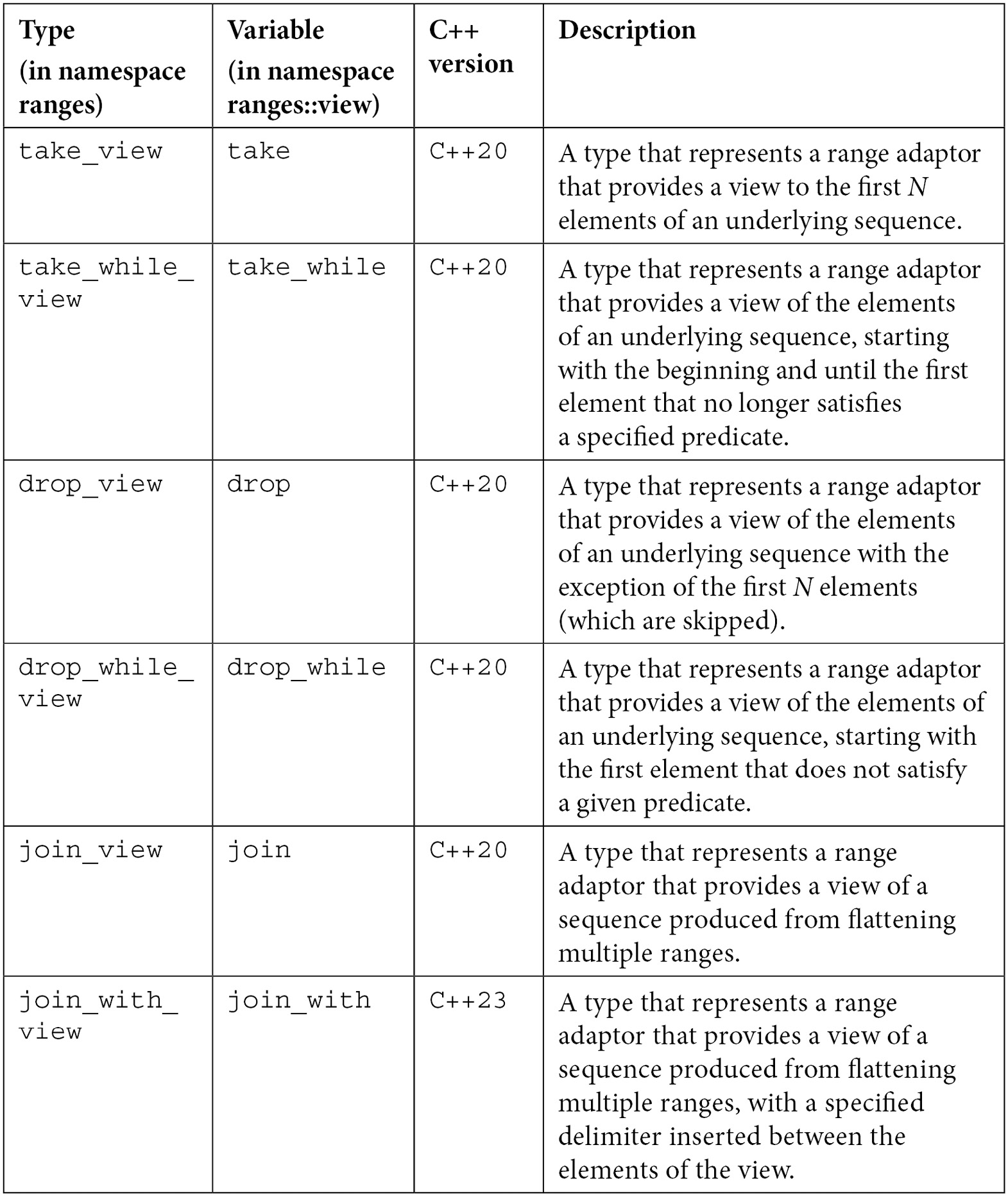

prices.push_back(price); });The examples given so far in this chapter included views such as filter, take, drop, and reverse. These are just a few of the standard views available in C++20. More are being added to C++23, and probably even more to future standard versions. The entire set of standard views is listed in the following table:

Table 9.4

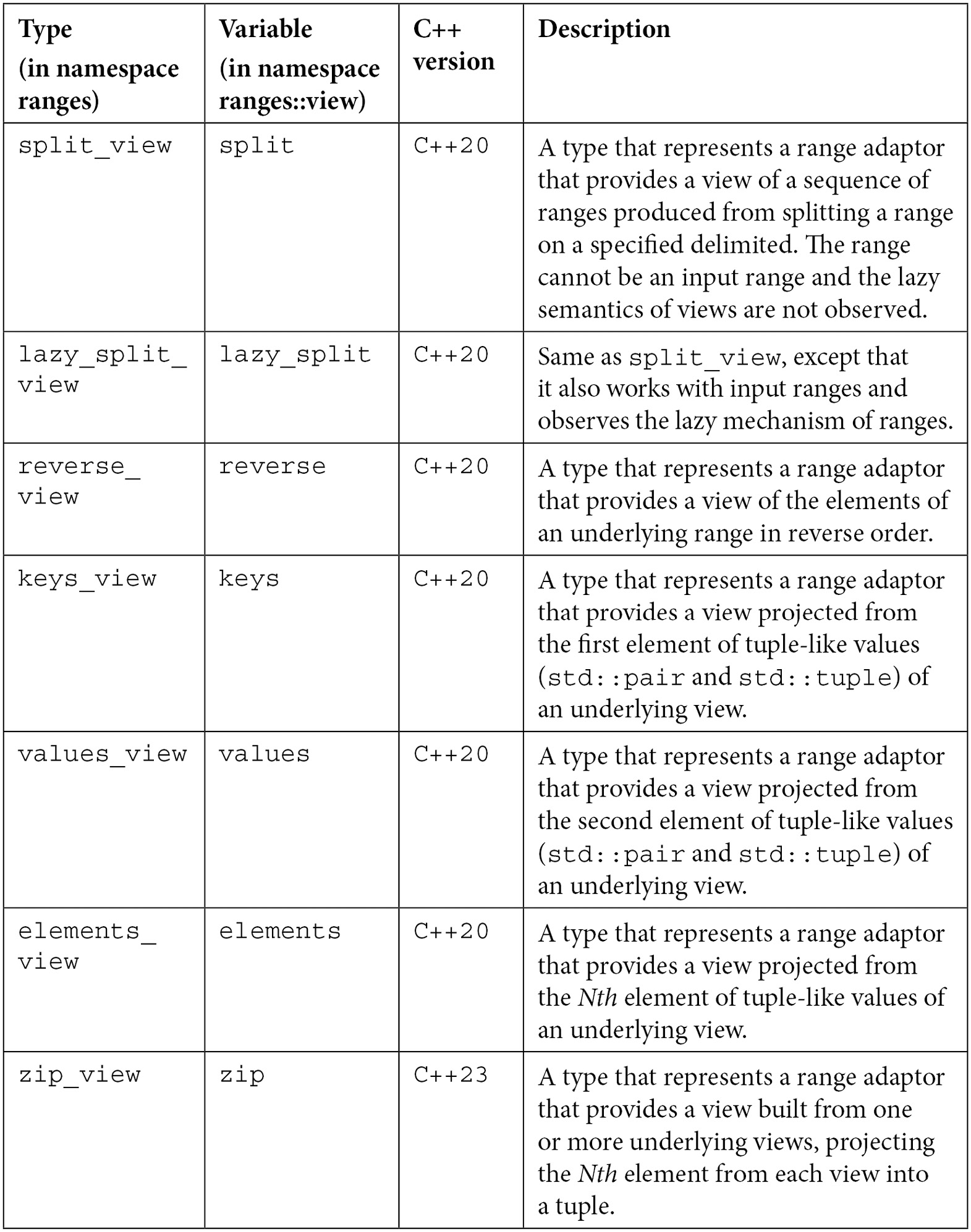

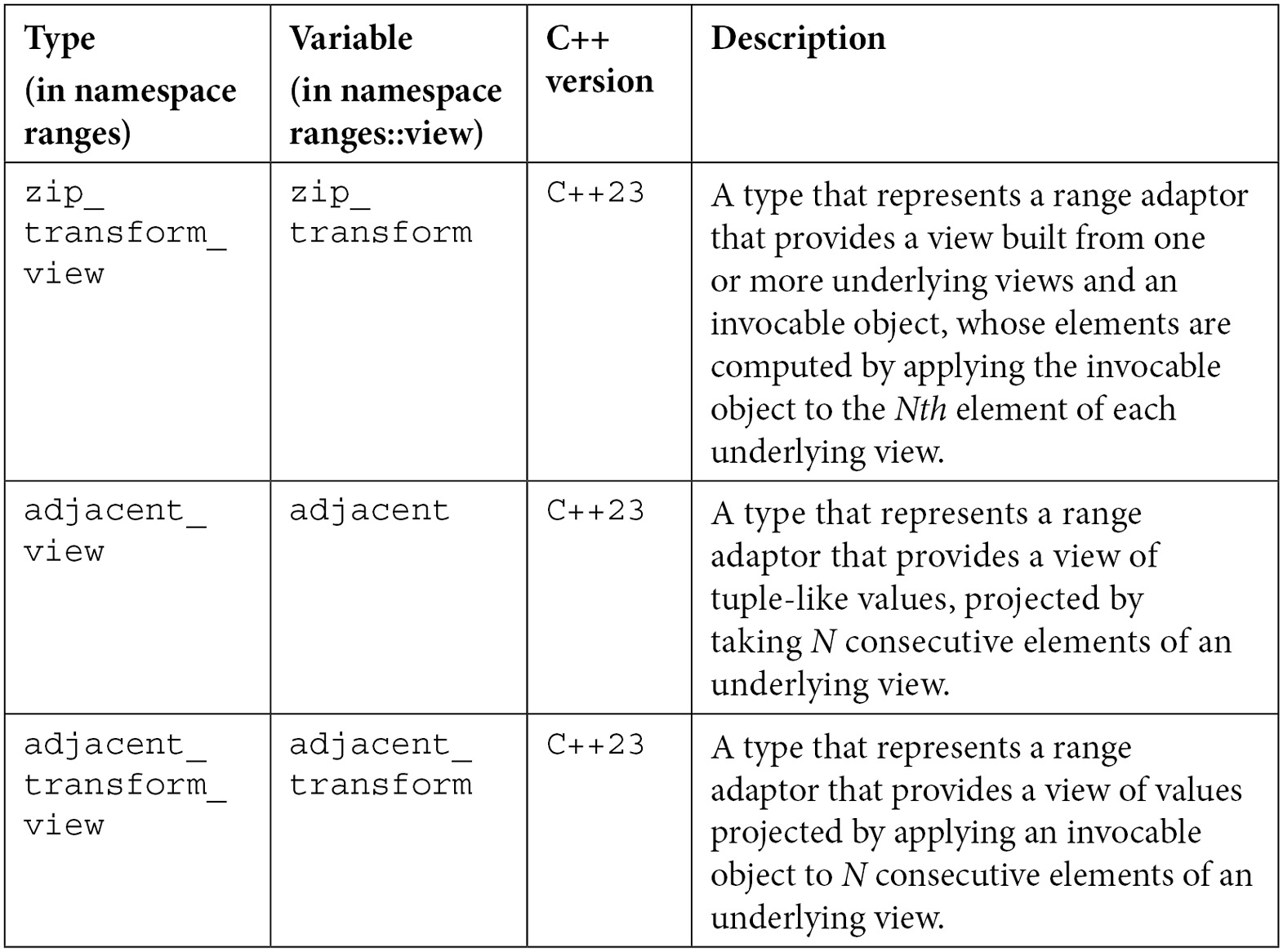

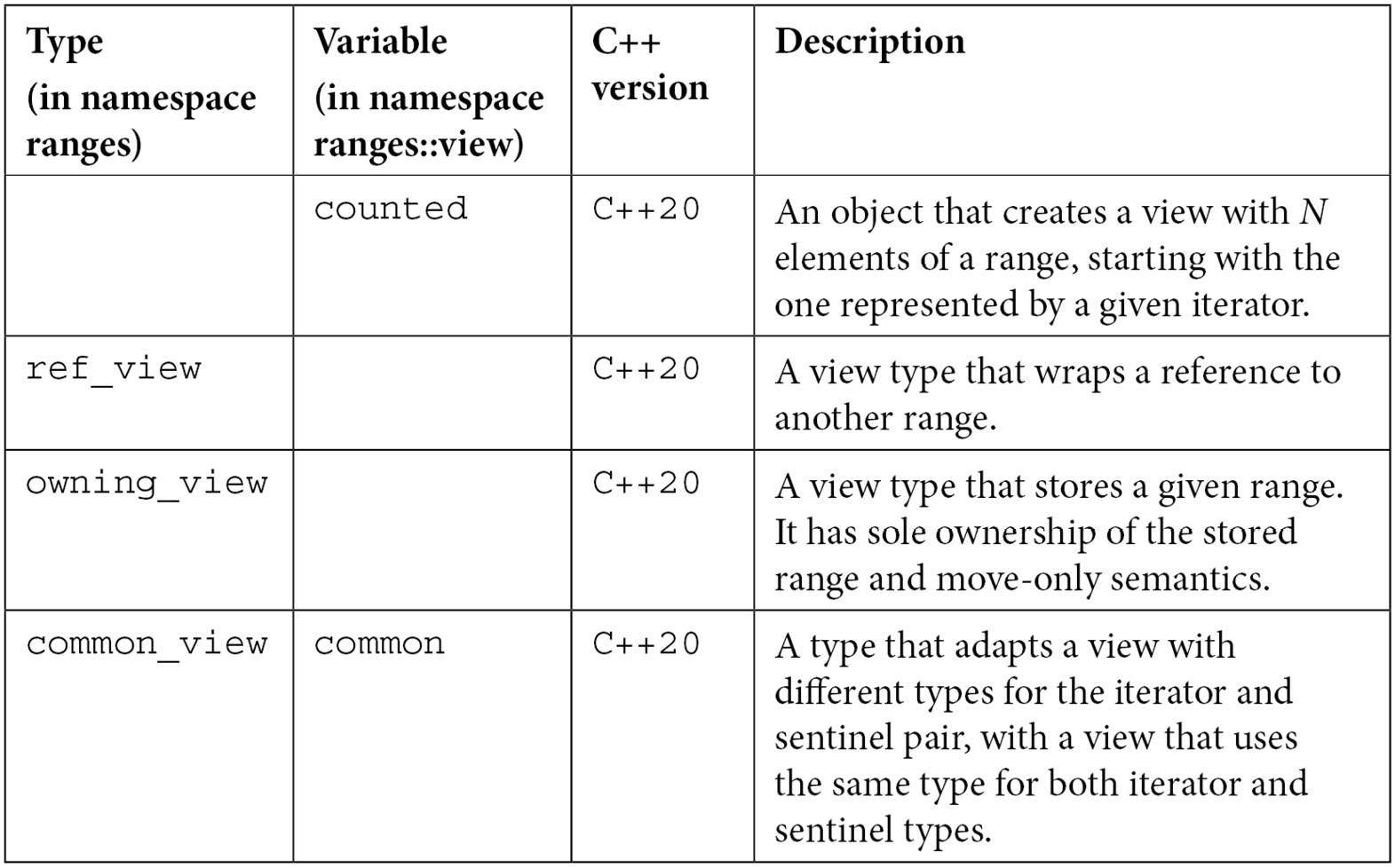

Apart from the views (range adaptors) listed in the previous table, there are a few more that can be useful in some particular scenarios. For completeness, these are listed in the next table:

Table 9.5

Now that we have enumerated all the standard range adaptors, let’s take a look at more examples using some of them.

Exploring more examples

Previously, in this section, we saw the following example (this time with explicit namespaces):

namespace rv = std::ranges::views;

std::ranges::sort(v);

auto r = v

| rv::filter([](int const n) {return n % 2 == 0; })

| rv::drop(2)

| rv::reverse

| rv::transform([](int const n) {return n * n; });This is actually the shorter and more readable version of the following:

std::ranges::sort(v);auto r =

rv::transform(

rv::reverse(

rv::drop(

rv::filter(

v,

[](int const n) {return n % 2 == 0; }),

2)),

[](int const n) {return n * n; });The first version is possible because the pipe operator (|) is overloaded to simplify the composition of views in a more human-readable form. Some range adaptors take one argument, and some may take multiple arguments. The following rules apply:

- If a range adaptor A takes one argument, a view V, then A(V) and V|A are equivalent. Such a range adaptor is reverse_view, and an example is shown here:

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 8, 7, 6, 4 };

namespace rv = std::ranges::views;

auto r1 = rv::reverse(v);

auto r2 = v | rv::reverse;

- If a range adaptor A takes multiple arguments, a view V and args…, then A(V, args…), A(args…)(V), and V|A(args…) are equivalent. Such a range adaptor is take_view, and an example is shown here:

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 8, 7, 6, 4 };

namespace rv = std::ranges::views;

auto r1 = rv::take(v, 2);

auto r2 = rv::take(2)(v);

auto r3 = v | rv::take(2);

So far, we have seen the likes of filter, transform, reverse, and drop put to use. To complete this part of the chapter, let’s take a series of examples to demonstrate the use of the views from Table 8.7. In all the following examples, we will consider rv as an alias for the std::ranges::views namespace:

- Print the last two odd numbers from a sequence, in reverse order:

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 4, 7, 6, 8 };

for (auto i : v |

rv::reverse |

rv::filter([](int const n) {return n % 2 == 1; }) |

rv::take(2))

{

std::cout << i << ' '; // prints 7 and 3

}

- Print the subsequence of consecutive numbers smaller than 10 from a range that does not include the first consecutive odd numbers:

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 5, 3, 2, 4, 7, 16, 8 };

for (auto i : v |

rv::take_while([](int const n){return n < 10; }) |

rv::drop_while([](int const n){return n % 2 == 1; })

)

{

std::cout << i << ' '; // prints 2 4 7

}

- Print the first elements, the second elements, and, respectively, the third elements from a sequence of tuples:

std::vector<std::tuple<int,double,std::string>> v =

{

{1, 1.1, "one"},

{2, 2.2, "two"},

{3, 3.3, "three"}

};

for (auto i : v | rv::keys)

std::cout << i << ' '; // prints 1 2 3

for (auto i : v | rv::values)

std::cout << i << ' '; // prints 1.1 2.2 3.3

for (auto i : v | rv::elements<2>)

std::cout << i << ' '; // prints one two three

- Print all the elements from a vector of vectors of integers:

std::vector<std::vector<int>> v {

{1,2,3}, {4}, {5, 6}

};

for (int const i : v | rv::join)

std::cout << i << ' '; // prints 1 2 3 4 5 6

- Print all the elements from a vector of vectors of integers but insert a 0 between the elements of each vector. The range adaptor join_with is new to C++23 and may not be supported yet by compilers:

std::vector<std::vector<int>> v{

{1,2,3}, {4}, {5, 6}

};

for(int const i : v | rv::join_with(0))

std::cout << i << ' '; // print 1 2 3 0 4 0 5 6

- Print the individual words from a sentence, where the delimited is a space:

std::string text{ "this is a demo!" };

constexpr std::string_view delim{ " " };

for (auto const word : text | rv::split(delim))

{

std::cout << std::string_view(word.begin(),

word.end())

<< ' ';

}

- Create a view of tuples from the elements of an array of integers and a vector of doubles:

std::array<int, 4> a {1, 2, 3, 4};

std::vector<double> v {10.0, 20.0, 30.0};

auto z = rv::zip(a, v)

// { {1, 10.0}, {2, 20.0}, {3, 30.0} }

- Create a view with the multiplied elements of an array of integers and a vector of doubles:

std::array<int, 4> a {1, 2, 3, 4};

std::vector<double> v {10.0, 20.0, 30.0};

auto z = rv::zip_transform(

std::multiplies<double>(), a, v)

// { {1, 10.0}, {2, 20.0}, {3, 30.0} }

- Print the pairs of adjacent elements of a sequence of integers:

std::vector<int> v {1, 2, 3, 4};

for (auto i : v | rv::adjacent<2>)

{

// prints: (1, 2) (2, 3) (3, 4)

std::cout << std::format("({},{})",

i.first, i.second)";

}

- Print the values obtained from multiplying each three consecutive values from a sequence of integers:

std::vector<int> v {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

for (auto i : v | rv::adjacent_transform<3>(

std::multiplies()))

{

std::cout << i << ' '; // prints: 3 24 60

}

These examples will hopefully help you understand the possible use cases for each of the available views. You can find more examples in the source code accompanying the book, as well as in the articles mentioned in the Further reading section. In the next section, we will discuss the other part of the ranges library, the constrained algorithms.

Understanding the constrained algorithms

The standard library provides over one hundred general-purpose algorithms. As we discussed in the introductory section for the ranges library earlier, these have one thing in common: they work with abstract ranges with the help of iterators. They take iterators as arguments and they sometimes return iterators. That makes it cumbersome to repeatedly use with standard containers or arrays. Here is an example:

auto l_odd = [](int const n) {return n % 2 == 1; };

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 };

std::vector<int> o;

auto e1 = std::copy_if(v.begin(), v.end(),

std::back_inserter(o),

l_odd);

int arr[] = { 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 };

auto e2 = std::copy_if(std::begin(arr), std::end(arr),

std::back_inserter(o),

l_odd);In this snippet, we have a vector v and an array arr, and we copy the odd elements from each of these two to a second vector, o. For this, the std::copy_if algorithm is used. This takes begin and end input iterators (defining the input range), an output iterator to a second range, where the copied elements will be inserted, and a unary predicate (in this example, a lambda expression). What it returns is an iterator to the destination range past the last copied element.

If we look at the declaration of the std::copy_if algorithm, we will find the following two overloads:

template <typename InputIt, typename OutputIt, typename UnaryPredicate> constexpr OutputIt copy_if(InputIt first, InputIt last, OutputIt d_first, UnaryPredicate pred); template <typename ExecutionPolicy, typename ForwardIt1, typename ForwardIt2, typename UnaryPredicate> ForwardIt2 copy_if(ExecutionPolicy&& policy, ForwardIt1 first, ForwardIt1 last, ForwardIt2 d_first, UnaryPredicate pred);

The first overload is the one used and described here. The second overload was introduced in C++17. This allows you to specify an execution policy such as parallel or sequential. This basically enables the parallel execution of the standard algorithms. However, this is not relevant to the topic of this chapter, and we will not explore it further.

Most of the standard algorithms have a new constrained version in the std::ranges namespace. These algorithms are found in the <algorithm>, <numeric>, and <memory> headers and have the following traits:

- They have the same name as the existing algorithms.

- They have overloads that allow you to specify a range, either with a begin iterator and an end sentinel, or as a single range argument.

- They have modified return types that provide more information about the execution.

- They support projections to apply to the processed elements. A projection is an entity that can be invoked. It can be a pointer to a member, a lambda expression, or a function pointer. Such a projection is applied to the range element before the algorithm logic uses the element.

Here is how the overloads of the std::ranges::copy_if algorithm are declared:

template <std::input_iterator I,

std::sentinel_for<I> S,

std::weakly_incrementable O,

class Proj = std::identity,

std::indirect_unary_predicate<

std::projected<I, Proj>> Pred>

requires std::indirectly_copyable<I, O>

constexpr copy_if_result<I, O> copy_if(I first, S last,

O result,

Pred pred,

Proj proj = {} );

template <ranges::input_range R,

std::weakly_incrementable O,

class Proj = std::identity,

std::indirect_unary_predicate<

std::projected<ranges::iterator_t<R>, Proj>> Pred>

requires std::indirectly_copyable<ranges::iterator_t<R>, O>

constexpr copy_if_result<ranges::borrowed_iterator_t<R>, O>

copy_if(R&& r,

O result,

Pred pred,

Proj proj = {});If these seem more difficult to read, it is because they have more arguments, constraints, and longer type names. The good part, however, is that they make the code easier to write. Here is the previous snippet rewritten to use std::ranges::copy_if:

std::vector<int> v{ 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 };

std::vector<int> o;

auto e1 = std::ranges::copy_if(v, std::back_inserter(o),

l_odd);

int arr[] = { 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 };

auto e2 = std::ranges::copy_if(arr, std::back_inserter(o),

l_odd);

auto r = std::ranges::views::iota(1, 10);

auto e3 = std::ranges::copy_if(r, std::back_inserter(o),

l_odd);These examples show two things: how to copy elements from a std::vector object and an array and how to copy elements from a view (a range adaptor). What they don’t show is projections. This was briefly mentioned earlier. We’ll discuss it with more details and examples here.

A projection is an invocable entity. It’s basically a function adaptor. It affects the predicate, providing a way to perform function composition. It does not provide a way to change the algorithm. For instance, let’s say we have the following type:

struct Item

{

int id;

std::string name;

double price;

};Also, for the purpose of the explanation, let’s also consider the following sequence of elements:

std::vector<Item> items{

{1, "pen", 5.49},

{2, "ruler", 3.99},

{3, "pensil case", 12.50}

};Projections allow you to perform composition on the predicate. For instance, let’s say we want to copy to a second vector all the items whose names begin with the letter p. We can write the following:

std::vector<Item> copies;

std::ranges::copy_if(

items,

std::back_inserter(copies),

[](Item const& i) {return i.name[0] == 'p'; });However, we can also write the following equivalent example:

std::vector<Item> copies;

std::ranges::copy_if(

items,

std::back_inserter(copies),

[](std::string const& name) {return name[0] == 'p'; },

&Item::name);The projection, in this example, is the pointer-to-member expression &Item::name that is applied to each Item element before executing the predicate (which is a lambda expression here). This can be useful when you already have reusable function objects or lambda expressions and you don’t want to write another one for passing different types of arguments.

What projects cannot be used for, in this manner, is transforming a range from one type into another. For instance, you cannot just copy the names of the items from std::vector<Item> to std::vector<std::string>. This requires the use of the std::ranges::transform range adaptor, as shown in the following snippet:

std::vector<std::string> names;

std::ranges::copy_if(

items | rv::transform(&Item::name),

std::back_inserter(names),

[](std::string const& name) {return name[0] == 'p'; });There are many constrained algorithms, but we will not list them here. Instead, you can check them all either directly in the standard, or on the https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/algorithm/ranges page.

The last topic that we’ll address in this chapter is writing a custom range adaptor.

Writing your own range adaptor

The standard library contains a series of range adaptors that can be used for solving many different tasks. More are being added in newer versions of the standard. However, there can be situations when you’d like to create your own range adaptor to use with others from the range library. This is not actually a trivial task. For this reason, in this final section of the chapter, we will explore the steps you need to follow to write such a range adaptor.

For this purpose, we will consider a range adaptor that takes every Nth element of a range and skips the others. We will call this adaptor step_view. We can use it to write code as follows:

for (auto i : std::views::iota(1, 10) | views::step(1)) std::cout << i << ' '; for (auto i : std::views::iota(1, 10) | views::step(2)) std::cout << i << ' '; for (auto i : std::views::iota(1, 10) | views::step(3)) std::cout << i << ' '; for (auto i : std::views::iota(1, 10) | views::step(2) | std::views::take(3)) std::cout << i << ' ';

The first loop will print all the numbers from one to nine. The second loop will print all the odd numbers, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9. The third loop will print 1, 4, 7. Lastly, the fourth loop will print 1, 3, 5.

To make this possible, we need to implement the following entities:

- A class template that defines the range adaptor

- A deduction guide to help with class template argument deduction for the range adaptor

- A class template that defines the iterator type for the range adaptor

- A class template that defines the sentinel type for the range adaptor

- An overloaded pipe operator (|) and helper functors, required for its implementation

- A compile-time constant global object to simplify the use of the range adaptor

Let’s take them one by one and learn how to define them. We’ll start with the sentinel class. A sentinel is an abstraction of a past-the-end iterator. It allows us to check whether an iteration reached the end of a range. A sentinel makes it possible for the end iterator to have a different type than the range iterators. Sentinels cannot be dereferenced or incremented. Here is how it can be defined:

template <typename R>

struct step_iterator;

template <typename R>

struct step_sentinel

{

using base = std::ranges::iterator_t<R>;

using size_type = std::ranges::range_difference_t<R>;

step_sentinel() = default;

constexpr step_sentinel(base end) : end_{ end } {}

constexpr bool is_at_end(step_iterator<R> it) const;

private:

base end_;

};

// definition of the step_iterator type

template <typename R>

constexpr bool step_sentinel<R>::is_at_end(

step_iterator<R> it) const

{

return end_ == it.value();

}The sentinel is constructed from an iterator and contains a member function called is_at_end that checks whether the stored range iterator is equal to the range iterator stored in a step_iterator object. This type, step_iterator, is a class template that defines the iterator type for our range adaptor, which we call step_view. Here is an implementation of this iterator type:

template <typename R>

struct step_iterator : std::ranges::iterator_t<R>

{

using base

= std::ranges::iterator_t<R>;

using value_type

= typename std::ranges::range_value_t<R>;

using reference_type

= typename std::ranges::range_reference_t<R>;

constexpr step_iterator(

base start, base end,

std::ranges::range_difference_t<R> step) :

pos_{ start }, end_{ end }, step_{ step }

{

}

constexpr step_iterator operator++(int)

{

auto ret = *this;

pos_ = std::ranges::next(pos_, step_, end_);

return ret;

}

constexpr step_iterator& operator++()

{

pos_ = std::ranges::next(pos_, step_, end_);

return *this;

}

constexpr reference_type operator*() const

{

return *pos_;

}

constexpr bool operator==(step_sentinel<R> s) const

{

return s.is_at_end(*this);

}

constexpr base const value() const { return pos_; }

private:

base pos_;

base end_;

std::ranges::range_difference_t<R> step_;

};This type must have several members:

- The alias template called base that represents the type of the underlying range iterator.

- The alias template called value_type that represents the type of elements of an underlying range.

- The overloaded operators ++ and *.

- The overloaded operator == compares this object with a sentinel.

The implementation of the ++ operator uses the std::ranges::next constrained algorithm to increment an iterator with N positions, but not past the end of the range.

In order to use the step_iterator and step_sentinel pair for the step_view range adaptor, you must make sure this pair is actually well-formed. For this, we must ensure that the step_iterator type is an input iterator, and that the step_sentinel type is indeed a sentinel type for the step_iterator type. This can be done with the help of the following static_assert statements:

namespace details

{

using test_range_t =

std::ranges::views::all_t<std::vector<int>>;

static_assert(

std::input_iterator<step_iterator<test_range_t>>);

static_assert(

std::sentinel_for<step_sentinel<test_range_t>,

step_iterator<test_range_t>>);

}The step_iterator type is used in the implementation of the step_view range adaptor. At a minimum, this could look as follows:

template<std::ranges::view R>

struct step_view :

public std::ranges::view_interface<step_view<R>>

{

private:

R base_;

std::ranges::range_difference_t<R> step_;

public:

step_view() = default;

constexpr step_view(

R base,

std::ranges::range_difference_t<R> step)

: base_(std::move(base))

, step_(step)

{

}

constexpr R base() const&

requires std::copy_constructible<R>

{ return base_; }

constexpr R base()&& { return std::move(base_); }

constexpr std::ranges::range_difference_t<R> const& increment() const

{ return step_; }

constexpr auto begin()

{

return step_iterator<R const>(

std::ranges::begin(base_),

std::ranges::end(base_), step_);

}

constexpr auto begin() const

requires std::ranges::range<R const>

{

return step_iterator<R const>(

std::ranges::begin(base_),

std::ranges::end(base_), step_);

}

constexpr auto end()

{

return step_sentinel<R const>{

std::ranges::end(base_) };

}

constexpr auto end() const

requires std::ranges::range<R const>

{

return step_sentinel<R const>{

std::ranges::end(base_) };

}

constexpr auto size() const

requires std::ranges::sized_range<R const>

{

auto d = std::ranges::size(base_);

return step_ == 1 ? d :

static_cast<int>((d + 1)/step_); }

constexpr auto size()

requires std::ranges::sized_range<R>

{

auto d = std::ranges::size(base_);

return step_ == 1 ? d :

static_cast<int>((d + 1)/step_);

}

};There is a pattern that must be followed when defining a range adaptor. This pattern is represented by the following aspects:

- The class template must have a template argument that meets the std::ranges::view concept.

- The class template should be derived from std::ranges:view_interface. This takes a template argument itself and that should be the range adaptor class. This is basically an implementation of the CRTP that we learned about in Chapter 7, Patterns and Idioms.

- The class must have a default constructor.

- The class must have a base member function that returns the underlying range.

- The class must have a begin member function that returns an iterator to the first element in the range.

- The class must have an end member function that returns either an iterator to the one-past-the-last element of the range or a sentinel.

- For ranges that meet the requirements of the std::ranges::sized_range concept, this class must also contain a member function called size that returns the number of elements in the range.

In order to make it possible to use class template argument deduction for the step_view class, a user-defined deduction guide should be defined. These were discussed in Chapter 4, Advanced Template Concepts. Such a guide should look as follows:

template<class R> step_view(R&& base, std::ranges::range_difference_t<R> step) -> step_view<std::ranges::views::all_t<R>>;

In order to make it possible to compose this range adaptor with others using the pipe iterator (|), this operator must be overloaded. However, we need some helper function object, which is shown in the next listing:

namespace details

{

struct step_view_fn_closure

{

std::size_t step_;

constexpr step_view_fn_closure(std::size_t step)

: step_(step)

{

}

template <std::ranges::range R>

constexpr auto operator()(R&& r) const

{

return step_view(std::forward<R>(r), step_);

}

};

template <std::ranges::range R>

constexpr auto operator | (R&& r,

step_view_fn_closure&& a)

{

return std::forward<step_view_fn_closure>(a)(

std::forward<R>(r));

}

}The step_view_fn_closure class is a function object that stores a value representing the number of elements to skip for each iterator. Its overloaded call operator takes a range as an argument and returns a step_view object created from the range and the value for the number of steps to jump.

Finally, we want to make it possible to write code in a similar manner to what is available in the standard library, which provides a compile-time global object in the std::views namespace for each range adaptor that exists. For instance, instead of std::ranges::transform_view, you could use std::views::transform. Similarly, instead of step_view (in some namespace), we want to have an object, views::step. To do so, we need yet another function object, as shown next:

namespace details

{

struct step_view_fn

{

template<std::ranges::range R>

constexpr auto operator () (R&& r,

std::size_t step) const

{

return step_view(std::forward<R>(r), step);

}

constexpr auto operator () (std::size_t step) const

{

return step_view_fn_closure(step);

}

};

}

namespace views

{

inline constexpr details::step_view_fn step;

}The step_view_fn type is a function object that has two overloads for the call operator: one takes a range and an integer and returns a step_view object, and the other takes an integer and returns a closure for this value, or, more precisely, an instance of step_view_fn_closure that we saw earlier.

Having all these implemented, we can successfully run the code shown at the beginning of this section. We have completed the implementation of a simple range adaptor. Hopefully, this should give you a sense of what writing range adaptors takes. The ranges library is significantly complex when you look at the details. In this chapter, you have learned some basics about the content of the library, how it can simplify your code, and how you can extend it with custom features. This knowledge should be a starting point for you should you want to learn more using other resources.

Summary

In this final chapter of the book, we explored the C++20 ranges library. We started the discussion with a transition from the abstract concept of a range to the new ranges library. We learned about the content of this library and how it can help us write simpler code. We focused the discussion on range adapters but also looked at constrained algorithms. At the end of the chapter, we learned how to write a custom range adaptor that can be used in combination with standard adapters.

Questions

- What is a range?

- What is a view in the range library?

- What are constrained algorithms?

- What is a sentinel?

- How can you check that a sentinel type corresponds to an iterator type?

Further reading

- A beginner’s guide to C++ Ranges and Views, Hannes Hauswedell, https://hannes.hauswedell.net/post/2019/11/30/range_intro/

- Tutorial: Writing your first view from scratch (C++20/P0789), Hannes Hauswedell, https://hannes.hauswedell.net/post/2018/04/11/view1/

- C++20 Range Adaptors and Range Factories, Barry Revzin, https://brevzin.github.io/c++/2021/02/28/ranges-reference/

- Implementing a better views::split, Barry Revzin, https://brevzin.github.io/c++/2020/07/06/split-view/

- Projections are Function Adaptors, Barry Revzin, https://brevzin.github.io/c++/2022/02/13/projections-function-adaptors/

- Tutorial: C++20’s Iterator Sentinels, Jonathan Müller, https://www.foonathan.net/2020/03/iterator-sentinel/

- Standard Ranges, Eric Niebrel, https://ericniebler.com/2018/12/05/standard-ranges/

- Zip, Tim Song, http://www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg21/docs/papers/2021/p2321r2.html

- From range projections to projected ranges, Oleksandr Koval, https://oleksandrkvl.github.io/2021/10/11/projected-ranges.html

- Item 30 - Create custom composable views, Wesley Shillingford, https://cppuniverse.com/EverydayCpp20/RangesCustomViews

- A custom C++20 range view, Marius Bancila, https://mariusbancila.ro/blog/2020/06/06/a-custom-cpp20-range-view/

- New C++23 Range Adaptors, Marius Bancila, https://mariusbancila.ro/blog/2022/03/16/new-cpp23-range-adaptors/

- C++ Code Samples Before and After Ranges, Marius Bancila, https://mariusbancila.ro/blog/2019/01/20/cpp-code-samples-before-and-after-ranges/