Testing or Examining— What’s the Difference?

Chapter highlights: |

|

We begin this chapter by teaching you a trick called “Lightning Squares.” Although limited in mathematical range, it is an impressive stunt you can show off to wow your friends and family. What’s great about it is that you don’t have to be proficient at math to do it. The only prerequisite is to be reasonably competent at doing the multiplication tables you learned in primary school.

By the end of this small, fun lesson you will be able to square any two-digit number ending in “5” very swiftly. In other words, in less than 10 seconds, you will be able to give the answer to: 152 or 15 × 15; 252 or 25 × 25; 352 or 35 × 35 … right up to 952 or 95 × 95. Do you have any doubts? Let’s try it out.

What is 352? The answer is 1225.

We got the answer in three seconds. Impressed? Try multiplying 35 3 35. You’ll get the same answer, but it will probably take you from 15 to 45 seconds. How did we do it so fast? Watch this:

Take 352 and break it into 3 and 52. The 52 at the end equals 25 (5 × 5). We now have 3 and 25.

Multiply 3 by (3 + 1) or 4, so multiply 3 × 4. The answer is 12. The answer to 352 is 1225.

Here’s a second example:

652

Break it into 6 and 52.

52 becomes 25, so you’re left with 6 and 25.

Multiply 6 × (6 + 1) or 6 × 7 to get 42.

The answer is 4225. Check by multiplying 65 3 65.

Now it’s your turn. The challenge is 452. Fill in the blanks.

| 452 Break it into ______ and ______. ______ becomes ______, so you’re left with ______ and ______. Multiply 4 3 (4 1 ______ ) or 4 3 ______ to get ______. The answer is ______. |

Turn the page upside-down to check your calculation.

| Answer: Break it into 4 and 52. 52 becomes 25, so you’re left with 4 and 25. Multiply 4 × (4 + 1) or 4 × 5 to get 20. The answer is 2025. |

The key is to take the first digit (for example, 4) and always add 1 to it (for example, 4 + 1 or 5); then multiply by the first digit (for example, 4 × 5 = 20). Then join with 25 (for example, 2025).

At this point, would you like to check to see if you’ve got it? Try 152 as fast as you can and write your answer in this box:

Check yourself by turning around the page.

| 1× (1 + 1) or 1 × 2 = 2 Answer: 225 |

Would you like to test yourself before we move along with this chapter? Try the following: 252, 752, 952. Time yourself for solving all three. You have 30 seconds. Go!

252 =_______ 752 =________ 952 =________

Here are the answers:

| 252 = 625 752 = 5625 952 = 9025 |

If you got all three right in less than 30 seconds, bravo! If you got all three right but it took a bit longer than 30 seconds, you’re on the right track. Just practice and try again. When you do each of them in less than 10 seconds, good for you! If you made errors, review the steps and try again. You’ll get it. We’ve never had a learner who didn’t eventually succeed.

If you got all three right in less than 30 seconds, bravo! If you got all three right but it took a bit longer than 30 seconds, you’re on the right track. Just practice and try again. When you do each of them in less than 10 seconds, good for you! If you made errors, review the steps and try again. You’ll get it. We’ve never had a learner who didn’t eventually succeed.

What Was That All About?

In case you haven’t figured it out yet, that was our introduction to the testing chapter. First we taught you something (starting with a rationale and performance objective). Then, after a little practice in which we faded out cues (we prompted you), we gave you a “test” (we released you). Did you feel threatened by the test? Did you feel that it was natural to see if you could do it? Did you feel good about yourself and your accomplishment when you succeeded?

When we provide instruction to learner groups, either live or via some other mode, such as a book, e-learning, or video, we always build in testing. Reflect on the “Lightning Squares” lesson you just experienced. Check off the items below with which you agree:

- 1. I felt stressed by the three test questions.

- 2. I felt at ease with the three test questions.

- 3. The test helped me check to see if I got it right.

- 4. The test helped me practice and remember.

- 5. The test helped me find what I had missed in the lesson.

- 6. The test and feedback were useful.

- 7. Thirty seconds? I did it in a lot less time!

- 8. I felt great about my success. I could do it!

When we present similar exercises and then check with adult learners, here are our typical findings:

- About 20 percent of the learners feel stressed. With some groups, it ranges up to 30 and 40 percent. They tell us, however, that the stress isn’t necessarily related to this test. It’s the word “test” that affects them and often makes them freeze up.

- About 60 to 70 percent of the learners are totally at ease with this form of testing. Many don’t even perceive it as a test. They read it as “check yourself.”

- Almost all our learners feel that this type of testing is helpful, stressful or otherwise. It seems like more practice but is presented in a more challenging—even stimulating—manner.

- Almost all the adults find that this type of test-practice helps them remember longer.

- If learners make an error on the “test,” they are happy to receive feedback and try again. In fact, in some cases the learners say they finally figured out the process through the testing and feedback.

- This reiterates what we just said: The testing and feedback can reinforce or add value to the lesson.

- We set a 30-second time limit knowing full well that most learners can do it in less time. That added sense of “I beat the test!” reinforces the learning and increases motivation. Caution: This has to be done carefully. The challenge has to be realistic and allow for satisfaction in meeting and, for those who can, beating the standard. It’s a delicate balance.

- Achieving success leads to pleasurable feelings in most learners. They overcame what they may have perceived as a difficult challenge. The effort that results in success provides an intrinsic reward. Learners who feel competent and confident about what they learned have a higher probability of reusing it back on the job. This may not be as a result of any training per se, but of the sense of accomplishment generated by confirmation of a valued achievement.1

Using the brief “Lightning Squares” lesson and debriefing, we can state the following key points about testing:

Using the brief “Lightning Squares” lesson and debriefing, we can state the following key points about testing:

- Testing is a natural part of learning. It helps both learners and trainers confirm performance objective attainment or identify where something is missing and requires corrective feedback.

- Testing doesn’t need to be threatening, but sometimes it is. (We will deal with this more in the next section on testing and examining.)

- Testing is an excellent way to teach. It lets the learner try out her or his learning with a bit of a challenge. The trainer or instructional component of a self-study lesson is pushed to the side. The learner, in a test situation, does all the work. Remember, the more meaningful work the learner does, the more the learner learns.

- Testing requires that feedback be given following the test. It either confirms objective attainment or offers corrective information specific to how the learner performed on the test, guiding her or him back on track.2

- Because testing requires active learner engagement, it should be used frequently. Meaningful engagement enhances comprehension and retention.

There is a “however” to all of this. Testing sometimes frightens adult learners, particularly those who may not have had great success with it in school. Anything that vaguely resembles a test (even a simple practice exercise with scoring or timing) can bring on anxiety and accompanying emotional push-back. This is a learned reaction to unpleasant past experiences. We’ll probe this further in the next section.3

Testing Versus Exams

At school you may have had weekly tests and then a final exam. In a courtroom, we are familiar with the lawyers “examining” and “cross-examining” the witnesses, probing for weaknesses in their stories. In fact, the whole concept of exams has become quite terrifying. No wonder so many people experience stress if they feel they are going to participate in an exam. (Medical personnel frequently note higher blood pressure levels in patients undergoing a medical “exam.”) Often those who take the exam feel as if it is not their skill and knowledge that is being examined, but they themselves. It is as if their own worth is being examined and brought into question. There’s not much difference for some people between the statements “You failed the exam” and “You’re a failure!” Incidentally, that perception is not restricted to low performers. Many high performers feel tremendous anxiety as well.4

We don’t want to overdramatize the point. We also are not therapists. What we do observe is that many people confuse testing in a natural, positive, educational manner with bad exam experiences and, therefore, erect barriers to an important learning activity. We define testing as an opportunity to verify whether or not the learner has attained the pre-specified objective. If yes, the learner must receive information either naturally by succeeding with the task or from the trainer/training in the form of a message, such as, “Correct,” “You’ve done it,” or “Perfect score.” If the learner has not met the performance objective, then this is an opportunity to identify where the difficulty lies and provide supportive, useful feedback with the possibility of retesting until the learner has succeeded in achieving the performance objective requirements.

One way of decreasing fear of testing is to employ terms such as “learning check” or “practice exercise.” Although this may sound like a euphemism, elimination of the word “test” can lower anxiety. This discussion brings us to a fundamental perspective on training. We train adult workers so that they will be able to perform in ways both they and the organization value. Training is by no means an end. It is a way to achieve organizationally desirable work performance outcomes by building required skills and knowledge. Our training should be designed to lead the adult learners simply, naturally, and directly from where they are to where they and the organization believe they should be.

To accomplish this, we analyze our learners to determine the current levels of their skill and knowledge. We specify the desired state. Then we build our training to create a path that leads them from “here” to “there.” Our performance objectives are the milestones. Our tests are checkpoints that perfectly match the objectives. This whole approach is often called criterion-referenced instruction—that is, instruction solidly anchored to the criteria for successful job accomplishment.5 The testing part is called criterion-referenced testing. It is the natural means for ensuring that the learner has met the objective at the appropriate standard of performance.6

If the training were for delicatessen counter workers to be able to slice a bagel into equal halves with smooth surfaces, then the test would be for them to demonstrate this performance. If they missed something (unequal halves or rough surfaces), then they would receive feedback and be tested (or given a new practice exercise) again until they succeeded.

Imagine that the following are objectives your adult learners have to attain. How would you test them in a criterion-referenced environment? Reflect on each one. Create a test item that is a perfect match for the objective and write it in the answer block following each objective.

- Given the ABC system, display the customer file in 30 seconds and on

the first try.

- Faced with a fire, select the appropriate procedure for combating it.

- Name the capitals of all the provinces of Canada, matching each capital to its province with no errors.

- From a collection of bones, identify the femur.

Table 9-1 presents our testing suggestions. Read them to learn how your ideas compare with our suggestions. Indicate your reactions to our ideas in the third column of the table.

Those four examples are intended to reinforce the idea of criterion-referenced testing. It means testing that perfectly verifies what the performance objective specifies. We will examine criterion-referenced tests in more detail soon.

Please note that the tests (or if you are getting comfortable with learning check, start using this term) to verify objective attainment are not necessarily exams. They could take the form of practice exercises, self-checks, team challenges, or en route checkpoints. In a formal setting they could become exams. What is key is that testing verifies performance objective success. In the learning environment, it should be done as naturally as possible to decrease stress that may inhibit performance. If exams are required, we recommend that you engage learners in sufficient test practice to replace their anxiety with confidence. Unless test-taking is somehow part of the job, focus on what learners are supposed to be able to do and not on the “test.”

What follows is an example from our experience that illustrates the point.

Sample Scenario: I’ve Been Working on the Railroad

All railway personnel who operate trains must go through a certification ritual every three years. Their work requires them to take exams on nine different subjects related to every aspect of handling a train. It includes a variety of content from inspecting airbrakes to marshalling trains to reading signals to applying specific regulations for different weather and track conditions. If they don’t pass all exams with a minimum of 85 percent, they don’t get their cards renewed. No card, no work.

Obviously, this can be a stressful time for railway personnel as they approach their exams. For the railway, it’s important to keep the locomotive engineers and conductors on the job. When we became involved at one railway, we found that the exams were mostly content centered rather than performance based and were more a set of reading tests than true verification of competency. Working with management, unions, and government examiners, we revised the exams so that they more closely matched what the engineers and conductors actually did on the job. We broke all the subjects down into major job tasks. We created lots of practice that tied closely to the tasks using clearly defined performance objectives. The practice exercises matched the objectives, and the practice tests matched the exercises. So closely was it all interwoven that training time radically decreased, and the exam success ratio shot way up. Best of all, the operational personnel found the testing easier although it was more job-application focused and contained 30 percent more test questions.

Table 9-1. Testing Suggestions Correlated to Performance Objectives |

| Performance Objective | Our Test Suggestion | Your Reactions |

| Given the ABC system, display the customer file in 30 seconds and on the first try. | Performance test: Give the learner a customer name. Have the learner interact with the ABC system to display the file. Check for accuracy, time, and number of attempts. | (Check all that apply.) |

| Faced with a fire, select the appropriate procedure for combating it. | Recall test: Show different types of fires (e.g., electrical, gas, flammable liquid). Have learner select the procedure from memory. (We have not asked her or him to combat the fire, only to select the procedure.) Verify accuracy of match. | (Check all that apply.)

I thought. |

| Name the capitals of all the provinces of Canada, matching each capital to its province with no errors. | Recall test: Have learners recite the provinces and their capitals from memory. Verify accuracy. | (Check all that apply.) I thought. |

| From a collection of bones, identify the femur. | Recognition test: Display bones. Name femur. Have learner point to it. | (Check all that apply.) I thought. |

When we used the old exam to test the engineers and conductors three months after they were recertified, many of them couldn’t attain the overall 85 percent passing grade. With the new approach, more than 90 percent scored 85 percent and higher three months and even six months after recertification. As one longtime railroader put it: “Before, I hated the exams and couldn’t sleep for days. With the new approach, my exam felt like all the practice tests I did on my own and in the class. No sweat!”

How Do I Go About Creating Tests?

This part of the chapter focuses on the nitty-gritty details of creating useful tests. We highly recommend you spend time on this section for three solid reasons:

- It will help you select and create valid tests.

- It has a lot of job aids that help cut down your time for test construction and guidelines for doing it well.

- We reviewed and condensed a great deal of material to prepare the few pages that follow. If you go through it, you will save all the time we had to spend.

Where to Start With Tests

Begin with your objectives. In the five-step model training session plan, you specify your overall and specific objectives. For each specific objective, you create a test item. Let’s imagine that you are going to train distribution center workers on how to operate a specific forklift vehicle. There are two prerequisites: They must have a valid driver’s license, and they must have written and passed the safety regulations test. Imagine that the first objective is to inspect the vehicle: “Given an XYZ-model forklift vehicle, you will be able to inspect it to determine mechanical soundness, safety status, and readiness for use, with no errors or omissions.”

Going back to what you learned in chapter 4, decide if this essentially requires declarative knowledge (talk about, name, explain) or procedural knowledge (activity, do, perform). Check your choice:

- Declarative

- Procedural.

The correct answer is procedural. Learners actually have to do something: conduct the inspection and determine status.

Examine the information in figure 9-1. It will help you decide what type of test you should construct for the forklift training. Because this is procedural knowledge, you turn right on the chart. That takes you to the question, “Covert procedure?” In other words, is this a procedure you cannot observe, such as doing a mental calculation? If it is, you are guided to provide the learners with a written or oral test and then ask them to recount to you orally or on paper what they did. You check off each step and/or decision they made as they tell you what they have done. This is the only way to determine if the right answer was the result of the right procedure. The forklift vehicle inspection is not a covert procedure, so you can create a performance test. To verify performance, we use one of the verification tools listed in figure 9-1.

Performance Tests and Verification Instruments

A performance test is an exercise you create to verify if the learner can do what is specified in the performance objective. Suppose the objective was, “Slice a bagel so that you get two equal halves and smooth surfaces. Do not injure yourself or anyone else.” Which of the following options would be an appropriate performance test?

- Here is a bagel, a knife, and a cutting board. Slice the bagel so that you end up with two equal halves and smooth surfaces, and do not injure yourself or anyone else.

- Explain to me the correct procedure for slicing a bagel so that you get two equal halves, smooth surfaces, and there are no injuries.

- Here’s a bagel that has been sliced. Tell me if it conforms to standards and justify your response.

The correct selection is 1, which matches the objective and calls for actual performance. If for safety, cost, resource, or other practical reasons you can’t have the learner do the real thing, then you can simulate it (use a mockup or a simulator).

If that’s not practical, test again but with objects that look like or represent the real thing and context. Reality is a credible way to verify (test) whether or not a person has met the performance objective. The problem: If there is any danger (that is, drive a forklift truck when you are not yet really competent or land an aircraft), then testing in a real-live manner could be disastrous. In most instances this is not a problem (that is, pull up a file from a database or slice a bagel). However, when danger exists or it is impractical to have the real thing present (for example, a locomotive airbrake in the training-testing setting), then a simulation of the real thing is the next best thing.

What is a simulation? Basically, it is a dynamic and simplified representation of a real or hypothetical system. It is based on a model of the actual system. The dynamic portion allows for manipulation of the system’s elements. As an example,

suppose you are training workers on how to troubleshoot the hydraulic system in the undercarriage of an aircraft. It would be impractical to bring in or immobilize a real airplane. So, we create a simulator that works like the real thing, but doesn’t have all of the other irrelevant parts of the aircraft. The simulator (a dynamic, simplified representation of the real undercarriage) allows for manipulation. Different problems are simulated on the simulator. Trainees learn to troubleshoot and get tested. Transfer of learning to the actual hydraulic system on the real aircraft is generally pretty strong. Some additional learning activities or support may be required when confronted with reality. Obviously, more testing will be required to certify that the trainees have mastered the job tasks.

What we’ve described here is a “high-fidelity” simulation system. It looks and feels like the real thing. Such simulators (the equipment) allow for a wide variety of simulations (realistic events, scenarios, and actions) to be played out. High-fidelity simulators and simulations, while effective, can be costly. Therefore, we may have to back off a bit and create lower fidelity simulations. These are not quite like reality, but they are still better than just talking about objects and situations. Backing further off from this type of simulation, we turn to scenario-based learning exercises. Notice that we are getting further away from the real world. Nevertheless, scenario-based instruction is still better than dealing with only words and abstractions. Scenario-based tests are more valid than essay writing for procedural tasks.

We always want to get as close to the real job situation as possible. We back away to high-fidelity, then low-fidelity, and then to scenario-based forms of instruction and testing because of danger, cost, resource constraints, time, and other practical factors that influence what is doable in the learning-testing context.

Two other issues to bear in mind with simulation are “psychological fidelity” and transfer to the job. In nearly all cases, simulations and scenarios are far more psychologically realistic than a discourse on some topic. However, sometimes a lower-fidelity simulation may create a stronger psychological sense of reality than a physically accurate representation of the “real world.” We have seen a hand-manipulated, three-dimensional cardboard pop-up visual aid displaying the organs of the body and how infection spreads affect villagers learning about reproductive health and sanitation more strongly than plastic, near-perfect representations that could be touched and handled.

With respect to transfer of learning to real life, again, simulation is more powerful than lecture or other forms of nonparticipative instruction. However, the more realistic the simulation has been, the easier it is to transfer the learning to a live situation. In all cases, guidance, practice, and support are necessary. Even with the most “authentic” physical and psychological simulations, some form of transition assistance is required. Learning checks that increasingly approximate reality and then real-world exercises and tests help cement learning and increase the probability of successful on-job performance.7

Creating Tests

There is no true way to measure procedural knowledge unless the learner performs for real, via simulation or through a scenario. Talking about it is not enough. Coaches can talk about successful sports plays but they cannot necessarily perform them.

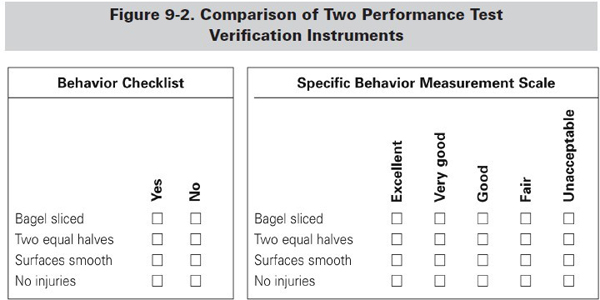

The performance test is half of what you create to test the learners on the objective. The other half is the verification instrument. This helps record how well each learner has performed. It is also useful for providing feedback. Table 9-2 is a list of performance test verification instruments. Browse through them to see the variety, advantages, and drawbacks of each. Choose your instrument based on which one best fits the situation.

Let’s return to the forklift example and the performance objective: “Given an XYZ-model forklift vehicle, you will be able to inspect it to determine mechanical soundness, safety status, and readiness for use, with no errors or omissions.” Here is a suitable performance test: “Conduct a complete inspection of forklift vehicle 23 (model XYZ). Check it for mechanical soundness, safety status, and readiness for use. Make no errors and leave nothing out.”

Which performance test verification instrument would you select? Review table 9-2 if necessary. Write your response in this box:

We selected the behavior checklist because we feel that the inspection largely consists of a series of actions or behaviors the learner either does or does not do (for example, verify for missing parts and check tire pressure). This selection does not eliminate additional notes made for feedback purposes.

In about 75 percent of all cases, the behavior checklist is the favored choice. It’s simple and easy to use. The second most common choice is the specific behavior measurement scale. The behavior checklist elicits “yes” or “no” answers for each item, and the scale measures the observation.

Table 9-2. Variety, Advantages, and Drawbacks of Performance Test Verification Instruments |

| Type of Instrument | Advantages | Drawbacks |

| Behavior checklist: Provides an observer with a list of behaviors the learner must demonstrate during a test. | • Is easy to develop. • Is easy to train observers. • Checklist items are simple and clear . • Provides concrete feedback to the learner. |

• Limits qualitative evaluation, especially for higherlevel competencies. • Does not lend itself readily to situations in which there is a wide range of acceptable behaviors. • If poorly designed, results in a high degree of observer subjectivity. |

| Specific behavior measurement scale: Provides an observer with a set of specific behaviors and a measurement scale for each. The scale is graded by level of competence. | • Provides a means for displaying different competency levels for different learner behaviors. • Decreases observer subjectivity. • Is relatively easy to train observers to use this type of instrument. • Provides learners with feedback during the learning process. |

• Takes longer to create than a checklist. • Is not useful if learner demonstrates behaviors not on the scale. • Is a bit awkward to use. • Is somewhat subjective. |

| Behavior frequency observation checklist: Provides an observer with a checklist that helps monitor frequency of a behavior or frequency of relevant and irrelevant behaviors. | • Produces a lot of data. • Demonstrates concretely the presence or absence of specific behaviors. • Can be used even if the learner deviates from targeted behaviors. • Can provide learners with feedback during the learning process. |

• Does not measure the degree of improvement of a behavior. • Requires considerable training of observers. |

| Behavior observation scale: Allows an observer to judge the appropriateness of using a behavior. When a variety of behaviors have been learned, each suited to a specific situation, this permits verification of the match between situation and behavior. | • Is easy to create. |

• The result depends on the ability of the observer to judge the appropriateness of a behavior. |

| Effectiveness checklist: Allows an observer to determine the effectiveness of a learner’s behavior. Focuses on results or outcomes. What is verified is the effect of the behavior, not the behavior itself. | • Effectiveness criteria have a high degree of credibility because they focus on results. • Is easy to train observers. • Provides learners with feedback on accomplishment rather than behavior during the learning process. |

• No attention to actual learner behavior. • Does not measure how the result was achieved. • Does not measure the costs of achieving the result. |

| Best responses: Allows for identification of several acceptable responses or solutions as best choices. | • Recognizes there are good, better, and best responses or solutions. • Recognizes that responses or solutions can be ranked in order of acceptability. |

• Does not allow for different ability levels for explaining how a response or solution emerged. • An excellent response or solution can be obtained without use of a targeted behavior. |

Figure 9-2 contrasts a behavior checklist for bagel slicing with a specific behavior measurement scale for that task. For bagel slicing, the behavior checklist definitely is adequate. For customer service, diagnosis, sales, conducting a sales meeting, and other less clear-cut behaviors where level of performance may be quantified along a continuum, the measurement scale may be a more appropriate model. In all cases, space for observations and comments can always be added to your instrument.

Written and Oral Tests

Continuing with our forklift example, imagine that one of the performance objectives is to name each of the gauges on the vehicle dashboard and explain its use. Turn back to figure 9-1. Examine the objective. Does it require procedural knowledge?

![]() Yes

Yes ![]() No

No

Naming and explaining require declarative (talk about) knowledge. The answer, therefore, is no. (On the chart, you turn left at the decision point.) To test for this performance objective we would employ some form of oral or written test with an appropriate answer key that contains the right answer. As you can see, there are several different oral and written tests. Binary or true/false items, matching tests (match the items in column A with those in column B), and multiple-choice test items are appropriate for recognizing the right answer. Here’s an example:

The “C” in a European temperature reading stands for

a. Centigrade or Celsius scale.

b. Color temperature scale.

c. Central European scale.

d. Centrifugal scale.

In this case, the learner need only recognize the answer, which is much easier than having to recall it. As the chart shows, for a recall-type performance objective, you could create a completion item (for example, “The ‘C’ in a European temperature reading stands for ________ or ________”) or a short-answer closed question (for example, “What does the ‘C’ in a European temperature reading stand for?”). Pushing it somewhat, you might even use an open-ended essay question (“Explain from where the ‘C’ in a European temperature reading is derived. What are the key benefits of this scale compared with that of the Fahrenheit scale?”). In table 9-3, we present brief descriptions of each of the types of oral and written test items and some key advantages and drawbacks.

We already have decided that for a performance objective that asks learners to name the gauges on the dashboard of a forklift vehicle and explain the uses of each one, an oral (or perhaps written) test would be appropriate. Check off the specific type of test you would select from the list below. You may check off more than one.

Table 9-3. Variety, Advantages, and Drawbacks of Oral and Written Test Items |

| Type of Test Item | Advantages | Drawbacks |

| Binary test: Offers learner two choices to select from, only one of which is correct. True/false and yes/no are the most common types. | • Is easy to correct and compile results manually, optically, or by computer. • Test instructions are easy to understand. |

• Range of responses is limited to two choices. • The test creator must possess strong mastery of the learning material. • There is a 50 percent chance of getting a right answer without knowing the learning material. |

| Matching test: Requires learner to match an item in one column with an item in a second column. Items in the second column are generally in random order. To increase challenge, the second column usually contains more items than the first. | • Is easy to create. • Is easy to correct. • Allows for many items to be tested simultaneously. • Is especially applicable for content that lends itself to pairing items. |

• Is restricted in application to objectives/content that lend themselves to pairing items. • Only tests low-level objectives. • Through process of elimination, allows for some guesswork. |

| Multiple-choice test: Requires learner to select the correct answer to a question from an array of three or four alternatives. | • Is easy to correct manually or mechanically. • Can include distracters that force discrimination between correct and almost-correct responses. • Permits testing of a large body of material fairly rapidly. |

• Generally is limited to factbased questions. • Does not allow for elaboration or explanation. • Takes a lot of skill and time to create excellent test items. • Requires good reading skills. |

| Completion test: Requires a one-word or several-words completion to a statement. Range of acceptable completion responses is limited. | • Limits the range of possible correct responses. • Is easy to correct manually using a correction guide or by computer. • Eliminates subjectivity. • Appropriate for problems with a limited number of possible correct responses. |

• Not appropriate for “why” and “how” questions. • The question itself may provide clues to the correct response. • Handwritten responses are difficult to correct mechanically. |

| Short-answer closed question test: Requires a brief, limited response from the learner. | • Is easy to create. • Is easy to check. • Is easy to insert during instruction. |

• Is limited in richness of response. • Takes longer to correct (written form) than do multiple-choice, binary, or matching items. • Can result in response variability. |

| Open-ended essay test: Requires an extended response that can also include learner’s opinion, interpretation, and vision. | • Is easy to create. • Allows for freedom of response by learner. • Appropriate for “why” and “how” types of objectives. |

• Requires strong subject matter knowledge to verify and give feedback. • Correction is labor intensive. • Allows highly diverse responses. |

Because the performance objective requires recall instead of recognition, we selected the short-answer closed question test. Our question would be “Name all the gauges on the XYZ forklift vehicle dashboard. Explain the uses of each one as you name it.” Our answer key would contain the name of each gauge with its position on the dashboard and a list of uses for each gauge.

As a final note on written tests of a formal nature, here are some useful guidelines to follow, regardless of the type of test items you create:

As a final note on written tests of a formal nature, here are some useful guidelines to follow, regardless of the type of test items you create:

- Keep course objectives clearly in mind. The test item must match the objective perfectly.

- Start with a few easy-to-answer questions to help relieve test anxiety among trainees.

- Write the test items at the language and reading level of the learners.

- Avoid negatives and double negatives in the questions.

- Construct questions and answers that are precise and non-ambiguous. Questions should have only one correct answer.

- Do not replicate statements from the participant manual. When you do so, you test memorization of the material and not comprehension.

- Make sure that the test items do not include clues about other test items.

- If this is a test following a unit of instruction, make sure that the answer to one test item is not dependent on the answer to another test item.

- Avoid trick questions that test the learner’s ability to guess, not his or her comprehension of the material.

- In a test covering a large body of material or a series of objectives, group same-type questions together—binary, multiple-choice, and so forth—to reduce the number of instructions and facilitate the learner’s task.

- Provide examples for complex question types.

- Provide clear instructions to the instructor about the length of the test and the material required. Provide him or her with answer sheets and correction guidelines.

- Try out the test and revise as needed before implementation.8

Checking for Test Validity

You have created a test item to verify whether the learner is able to meet the objective. You may have even prepared several test items for each objective for practice, at the end of some part of the training, and to include in an overall test at the end. How do you ensure that your test items, even for practice purposes, are valid (that is, they truly test what the objective requires)? We have included a job aid to help you make this final check. Take a look at checklist 9-1.

Checklist 9-1. Test Item Verification Job Aid |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Remember This

Given the nature of this book, we have often resorted to binary and matching end-of-chapter “tests.” As you have noticed, we do this to help refresh some key chapter points, not to verify against objectives. This book is not a course; it is a sharing of our experience and research along with some exercises to illustrate and help you retain key points.9 So, as usual, we conclude this chapter with your final exercise. Cross out the incorrect word or phrase in the parentheses below:

- The word “test” (often/rarely) creates tension and stress for learners who have not had successful school experiences.

- Generally speaking, (low / high / both low and high) performers suffer from test anxiety.

- Testing (is / is not) a natural part of learning.

- Testing is (an excellent / a poor) way to teach.

- Key to successful testing is providing learners with (a score/feedback).

- Testing should occur (throughout / only at the end of) training.

- Criterion-referenced instruction is closely tied to (the content of the course / the requirements for successful job accomplishment).

- The starting place for a test item is the (performance objective / the course content).

- In simulation testing, the learner faces (dynamic representations of real or hypothetical systems / abstract notions not resembling real or hypothetical systems).

- For procedural knowledge, use (written or oral / performance) tests.

- For declarative knowledge, use (written or oral / performance) tests.

- The answer to 852 is (7225/4225).

Now here’s our feedback for you:

- The word “test” often creates tension and stress for learners who have not had successful school experiences. This can also be true of high performers who are perfectionists lacking confidence. Use “test,” “exam,” “evaluate,” and “measure” sparingly. Use “practice,” “check yourself,” or “game” more frequently with adult learners.

- Generally speaking, both low and high performers suffer from test anxiety. Those who suffer from strong test anxiety usually do more poorly than those who are not as anxious. However, high-performing learners suffer almost as much as poor performers and thus lower their scores on tests.

- Testing is a natural part of learning. A test is a trial. You learn. You want to see if you can do it and if you know it. When the test becomes a means for judging the person, however, there are dangers of inhibiting performance and diminishing motivation to learn.

- Testing is an excellent way to teach. The key is to make it fun and challenging, not stressful. It mentally engages the learner and enhances retention.

- Key to successful testing is providing learners with feedback. If the learner has made a response, the probability that she or he will actively attend to the feedback information is increased. Increased attention to meaningful feedback, whether corrective or confirming, helps learning.

- Testing should occur throughout training. Frequent verification of performance objective attainment and feedback decrease the chance of learning gaps that can grow ever wider as training progresses. Testing also helps consolidate learning.

- Criterion-referenced instruction is closely tied to the requirements for successful job accomplishment. The whole learner-centered and performance-based approach is to prepare the adult learner for the job. The ideal of criterion-referenced instruction is that 100 percent of the learners will achieve 100 percent of the performance objectives that are derived directly from the job.

- The starting place for a test item is the performance objective. All through this chapter and right to the last job aid, the emphasis has been on perfectly matching test items to performance objectives.

- In simulation testing, the learner faces dynamic representations of real or hypothetical systems. Simulation is a dynamic and simplified representation of a real or hypothetical system. Either a system exists such as the solar system or is made up such as Wonderland in Alice in Wonderland. The simulation mirrors the system, and the learner deals with its elements to try things out or solve problems.

- For procedural knowledge, use performance tests along with performance verification instruments. For covert procedural knowledge, use correction checklists to verify what the learner did mentally.

- For declarative knowledge, use written or oral tests. Include answer keys. These give learners the opportunity to display their talk-about knowledge.

- The answer to 852 is 7225. We just wanted you to practice. Did you answer in less than 10 seconds?

You have come a long way since chapter 1. You’ve been inside your learners’ minds; structured their training; developed strategies to strengthen learning; and developed activities to engage them and enhance their motivation, skills, and knowledge. And you’ve tested them to ensure that they can meet the learning objectives and perform well on the job.

We now introduce a new dimension to continue building your expertise as a training professional. The next section offers you two extensive chapters on technology and training-learning. About one third of workplace organizations in the United States employ some form of computer-driven technology to deliver online training. Technology has always been part of the training-learning world. In 1913, Thomas Edison predicted the disappearance of the classroom as a result of the introduction of the moving picture.

The next section presents a balanced approach to technology in the training world. Its purpose is to arm you with information to consider; suggestions on how best to employ the array of technological marvels available to help meet learner needs; and precautions to retain as you explore new, enticing, electronic possibilities.