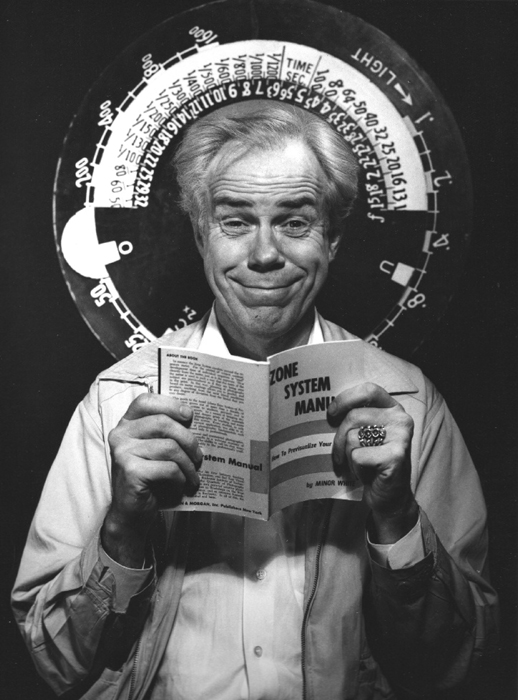

Minor White Teaching the Zone System; 1962, by David Spindel, Rochester Institute of Technology, NY, student of Richard Zakia

14

Teachers on Teaching

“As a teacher I am committed to providing an atmosphere in which people might be able to learn and experience by means of photography the whole spectrum of visual experience embodied in the two phrases, ‘things for what they are’ and ‘things for what else they are.’”

Minor White

While we have written about our approach, experiences, concepts, and concerns about teaching photography and imaging, we are using this chapter to share the insights and beliefs of many colleagues. The following contributions by these colleagues show some of the diversity of thought and concern in today's photographic education.

Roy R. Behrens

University of Northern Iowa, IA

For 35 years, I have taught at American art schools and universities. Much of what I teach, I may have obtained inadvertently through photography.

I recall that I learned some of this in the 1960s as an undergraduate art student, partly because one of my finest professors was an articulate photographer, who, whenever he was asked to teach a design course, used photographic examples in his lectures instead of paintings, prints, and sculpture, the so-called “fine arts.”

It took courage to teach photography then. It was not a welcome subject in American art departments, because almost everyone assumed that making images with a camera was not genuine Art. It was seen largely as “commercial,” and at best it was a mechanical feat, produced by causing light to make certain patterns on chemically treated surfaces. It was not a “self-expressive” art, since any person off the street, with or without any training, could make a photograph.

Now, some 40 years later I increasingly realize that I teach in ways that emphasize photography, both historic and contemporary. Like my former professor, when I talk to students, I tend to use photographic examples. When I invent new studio problems, I prefer to add provisions that require students to originate their own imagery, primarily through photography.

I have a vivid memory of the first time I assigned such a problem: It was the spring of 1968, and I was a 21-year-old college senior—not a teacher but a “student teacher”—in charge of a class of high school art students. A year or two before, the professor I mentioned earlier had urged me and my classmates to look closely at the books of Gyorgy Kepes, especially Language of Vision and The New Landscape in Science and Art.

The latter was to great extent an archive of scientific images, produced by such non-art techniques as aerial photography, high-powered microscopes, stroboscopic photography, x-ray, time lapse, infrared, and so on. The resulting images were “objective records” of reality, and yet they were no less exotic, and no more identifiable, than were the abstract paintings that Kepes purposely paired them against on the facing pages of each spread.

One day I asked my students to bring to class a simple snapshot camera. I then sent everyone outdoors for an entire class period, with instructions to make photographs of settings on the school playground in such a way that the objects in the photographs would be unrecognizable (because of framing, point of view, the patterns of shadows, and so on). I remember how astonished the students and I were by the eerie, new, and provocative forms that resulted…“making the familiar strange.”

Over the years, as technology has evolved, so have my classroom uses of photography. Today's students are likely to use digital cameras or flatbed scanners as if they were cameras, thereby producing breathtaking details by the direct scanning of real objects.

In teaching, I show my students how their work can have a stronger and far more enduring effect if they can anticipate how people see, in the sense of just generally being aware of perceptual biases that are not culture-laden, but hard-wired in the brain.

My own acquaintance with these “principles of visual organization” also took place while I was an undergraduate. I eventually determined that the effectiveness of camouflage is directly contingent on the same organizing principles that designers use in typesetting, in page layout, or in selecting, cropping, and placing an accompanying image. As everyone knows, sleight-of-hand magicians and pickpockets make constant and highly reliable use of these same tendencies, on a level that is not determined by cultural conditioning or by self-expressive drives.

I sometimes give out problems that deal explicitly with camouflage. But the same principles can just as easily be addressed by requiring students to produce what used to be commonly called “trick photography,” in which, typically, two physically separate entities are made to look connected in the photograph, or a normally continuous form appears to be two things instead. These same tendencies can also be taught by exercises in “metaphorical seeing,” in which one creates visual puns, surreal juxtapositions, and other varieties of visual ambiguity.

In publication design, it is often said that the major twin components are text and illustration, or type and image. By using photography when I teach, I am able to address both of these at once, since students not only become familiar with organizing principles, they also gain experience in the creation and inclusion of photographic images, in tandem with typography, within the context of a page.

Finally, and of particular value, I think, they also come to understand that typography (the choice and arrangement of type on a page) is governed by the same organizing principles (the unit-forming factors of similarity, proximity, continuity, and closure) that are the major syntactical tools in the design of photographs.

Corinne Rose

Museum of Contemporary Photography, IL

On Teaching Photography

As a college art museum, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia College Chicago's primary goal is education. On a daily basis we use our changing exhibitions and print study room, which houses a collection of close to 7,000 original photographs as a teaching resource to initiate dialogue on a variety of aesthetic, social, political, and cultural issues with students of all ages.

By Jaren Hillard, Providence St. Mel School, IL, student of Joel Wanek and Aoko Hope

The intensive teaching that we do at the museum is with teens. We run three after-school outreach programs that engage urban teens in using photography as a means to examine and explore their lives and communities. Taught by graduate students and adjunct faculty from Columbia College paired with classroom teachers, participating students gain a solid foundation in the fundamentals of analog and digital photography through assignments such as exploring vantage point, observing light and shadow, and using and controlling motion and depth of field. While learning these technical skills, students photograph a variety of subjects, including their families and friends and the urban landscape of Chicago, and are mentored by their teaching team, museum staff, and visiting artists. For inspiration, students periodically visit the museum to view and discuss master works from the museum's collection. Graduates of our programs have gone on to receive scholarships and study photography at institutions, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Pratt Institute, the London College of Art and Design, and Columbia College Chicago.

Two years ago, the museum held an exhibition titled Conversations: Text and Image that featured artists who combine words and pictures in the creation of their work, including Jim Goldberg, Lorna Simpson, and Walker Evans, among others. In conjunction with this exhibition, we sent writers drawn from the college's Fiction Writing Department to work with our teens to create writings to pair with the images they were creating in class. The classroom teachers were thrilled to see photography's power to inspire even the most reluctant writers—many of the students we serve write below grade level and are intimidated by writing. We were surprised and moved by the intensity of stories that the students were willing to share and by how much their writings added to the depth of their final compositions. This project was such a success that we continue to include creating works combining text and image in our photography curriculum and have partnered with other organizations, including Columbia College's Center for Community Arts Partnerships, Project AIM, to bring this curriculum to a wider group of students. For the past two years the museum has exhibited these works in a now annual exhibition titled Talkin' Back: Chicago Youth Respond.

The image accompanying this writing was created by Jaren Hillard in a program led by teaching artists Joel Wanek and Aoko Hope at Providence St. Mel School on Chicago's Southwest side. Wanek says, “Jaren was really interested in photographing architecture and the landscape. This image of his niece and nephew playing is one of the few ‘people pictures’ that Jaren made in our class—it wasn't an image that he was particularly excited about. I don't think he realized the tension and ambiguity inherent in this photograph.”

Wanek and Hope encouraged Jaren to expand upon this image in a workshop with visiting writer Jennifer Morea. Morea says, “I asked the students to ‘interview’ the character in their photograph and write down responses to questions I posed as if it were the response of the person in the photograph. I began by asking students to find something subtle, or what seemed maybe to be a minor thing, that was most interesting to them about their photograph. I asked them ‘what do you think the person in the photograph is saying or is trying to say just by how he or she looked in the image?’ In the voice of their subjects, students wrote notes in response to questions such as Who and what do you feel connected to? What is the most difficult thing in life for you? What is something kind someone once did for you that you'll never forget? and Where are you going, where have you been?”

Jaren's final piece demonstrates the eloquent force of the voice and vision of our youth, realized when they are empowered to express themselves creatively.

John Fergus-Jean

Columbus College of Art and Design, OH

Image and Afterimage

One of the most important aspects of teaching photography is its capacity to tell a “story.” In my teaching I focus on two aspects of story within student photographic images, the image proper, the tangible photograph, its form, content, and syntax, and what I call the afterimage, the intangible meanings within the photographic process that reveal the student's own personal story.

At the core of my teaching is connecting the personal narrative of both the maker and the observer to any photograph. This renegotiation of meaning results from creative and essential fictions, the tangible, the intangible, memory, and the linking of images to self. This applied search for meaning, the process I call afterimage, is the uncovering of fuller dimensions of meaning through extended internal and external dialogue, and by sharing one's own story.

Viewed in this light, it can be said that students bring their own personal meanings to the images they make. Indeed, it is the sharing and retelling of such story that encourages a renegotiation of image content, which can lead to growth and change. It is precisely because we bring our stories to images, that personal narrative is as important in the pursuit of art as any learned technique.

Afterimage is thus an ongoing process, the creation of stories we make up time after time, for the task of finding our current meanings in image. Thus, in afterimage is the transformative potential of image to elicit change and growth. The authenticity of such story flows from the makers' ability to imagine and reimagine their own lives in their own terms. This is the vital link that connects the image and the territory of lived experience.

In contrast, in many academic circles highly evolved and convincingly articulated art speak narratives often lead to mystifying dialectics that have come to shape the art school experience. In essence, such processes involve displacement, the displacement of one's own personal story into meta-stories that seem to just be there. I believe what students get from this approach is an affirmation of self-validation that their story is also their reservoir, their vital inner keel for navigating through the world.

By honoring personal story, the student image-makers become the nexus of image and afterimage, the extended function that posits image-makers as storytellers, who express setting, time and place, point of view, persona, the events of the story, and the story's worth to the now of their lives.

Metaphorically speaking, remembrance involves a familiar photographic pattern that has a less familiar inner correlation: exposure, development, and fixing.

Exposure — taking, making, showing of images, wherein each phase of exposure creates new opportunities to revisit and reencounter image content. Each aspect allows the discovery of content.

Development — the extended mental processes that guide one's relationship to image, the aspect of coming to understand; and the honoring of dialogue as a way to give additional form to content.

Fixing — the remembering, reimagining, and transforming of relationship through insight, comprehension, and growth. Simply put, the affirmative and healing power of retelling and creating story.

Remembrance leads to critical thinking and requires students to describe, analyze, interpret, and judge their created works within the context of their own meanings and the outer language used to express those meanings. Ultimately these meanings converge with ideas at the core of the humanities, and by extension they lead to the ways media observe and represent the world.

Thus in essence, my approach to teaching involves the means for personal growth, by transcending technical and analytic considerations, to find semantic depth through personal voice. As a teacher, I feel to engage such a fuller sense of connection is a healing function based on the power of honoring the student's personal voice by allowing them to proclaim, “This is what I think, see, and feel.”

Misun Hong

Sookmyung Women's University, Korea

An old Korean saying states, “Don't even step on a master's shadow.” In the Korean tradition, teachers are viewed as icons, both morally and spiritually, and thus are treated with utmost deference. Everyone, including students and their parents alike, maintains absolute respect for a teacher. Although these days the position of teachers has changed somewhat, they continue to be esteemed in Korean society. Reflecting on my experiences with the teachers and students I have met, I can summarize the most important points to observe in the classroom as the relationship between the teacher and students, the conveyance of praise and encouragement, and the exploration of students' talent.

The most important point in the classroom is the maintenance of good communication and response between the teacher and students. Teaching in a classroom is like performing on a stage. A well-prepared lecture elicits a good response. If the lecture is not adequately prepared, the result is a regretful performance. Yet even when presenting the same lecture, the outcome can vary depending on the response of students. In order to maintain good communication and response in the classroom, the relationship between teacher and students should be horizontal. This relationship is particularly important in an art class, which requires imagination and creativity. For this reason, any and all questions and ideas should be discussed in class. Teachers should help students to solve problems and to follow their thoughts through feedback in class.

The next important aspect of the teacher-student relationship is praise. I am deeply indebted to the teachers who recognized my talent and praised it, and as a result of their support I pursued my study of photography without giving up in the middle. Praise from teachers gives students confidence in the subject and encourages them to study more in that field. It is natural for a teacher to praise good students, but a true educator is the teacher who stimulates interest among students who, for whatever reason, are less responsive to the subject. In this regard, assignments, tests, and critiques are vitally important. Various methods should be explored in order to search for students' hidden potential. Critiques and grades should be given with sincerity. An inappropriate critique can lead students to think that they have no talent, and have the unfortunate result of their losing interest in the subject.

The final important point is to discover and highlight students' latent talent. The teacher's job is to motivate students so that they discover their own concerns. Teachers should continually and closely observe their students to discern their interests and strengths. Specifically, teachers help students to realize their own potential, their desires, their interests. In the class “Understanding Photography,” I ask students to show photographs that interest them, and then to explore their own attraction and feelings about the photograph. By the end of the semester, the students each have revealed an individual character as unique as their face. I have taught that class for more than 10 years, but it remains fresh.

Even if the primary aim of teaching is to convey knowledge and information, I think that care and love are important elements required for the realization of that goal. Students find their own path and get to know themselves through experiences with many classes and many teachers. I now realize that, like the sun, students give me new energy as time goes by.

Sean Perry

Austin Community College

A Chance to Be Lucky…of Game Theory and Good Photographs

I am surprised every semester at the volume of good photographs exhibited by the Fundamentals class in the student print show. The photographs are consistently better as a group than are those from any other section; I had always struggled to explain why…until I read an article on Game Theory. Game Theory is a mathematical construct that determines an optimal course of action based on the logical choice being selected from available options. It is a buzzword in many circles these days, being applied to everything from economics to evolutionary biology. A simple truth of this system is that the fewer options available, the higher the probability that success will be achieved.

Record Holder — 100 meter Butterfly; by Lance Holt, Austin Community College, TX, student of Sean Perry

The Fundamentals class illustrates this concept perfectly. The students have one camera, one lens, and a single type of black and white film. There are no flash units or tripods. Within these limitations a beautiful phenomenon occurs in which the distance between emotion and final image is reduced. Free from the fog of unnecessary choices, these students enjoy a more intimate relationship with their subject. A limited choice of tools increases the probability of making a successful image. They have given themselves a better chance to be lucky, to be in the moment.

Complex concepts can be stated in simple equations and metaphors. The medium of photography by its very nature is a simplification. Placing a frame around a scene, focusing on a particular point, exaggerating contrast and tonality. These are all tools to place heightened interest around a subject and reduce the peripheral. In one still frame, the power of life force and expanse of the human condition can be simplified and communicated across class, culture, and time. The making of this magic is frequently lost when the method or equipment clutters the attention of the moment. I have observed artisans who act with a determined will to master their toolbox in order to magnify expressive intent. I strive to instill a desire in my students to earn their tools, to grasp what will make plain the story of an image, not convolute it, to resist being seduced by the latest, greatest, shiniest widget.

Elite athletes will often say “I give myself the best chance to win.” They focus on what the moment requires and edit out the superfluous. It's a fundamental element of how to elevate and respond. Photography is about getting to the heart of an image—which is greater than its subject. Strong teachers transcend material, identify a path of focused attention, and illuminate a destination of expressive imagery. It is the difference between teaching and inspiring.

Mariah Doren

Central Michigan University, MI

Traditionally critiques are used as a forum to evaluate work with the goal of helping students improve their practice as artists. I have adopted a format for in-class critiques that is derived from the work of Edmond Burke Feldman. This method models behavior that promotes students' engagement of the world both interior and exterior to their art practice. It leads a student through a method of critique while promoting direct participation in discussion by all students. They are engaged in the democratic process of constructing meaning in our culture.

In the critique there are four levels of analysis: description, formal analysis, association, and reflection. The first level is description of the image. We go around the room, each student adding one item to our inventory of the image. The time it takes to create a list of observed facts also gives the class the space to really look at the image. The second level is a formal analysis that comes directly out of the description. Formal analysis describes the compositional choices, elements and principles of design, as well as things specific to photography like choice of lighting, depth of field, and contrast. The third level of analysis is when the students talk about their associations with the work. This is the heart of the critique. The questions posed are “What does the image remind you of, make you think about, and how does it make you feel?” During this section of the critique the impressions formed are a combination of the artist's choices and the viewer's experiences. There is a dialogue between the image and the viewer. The conversation sparked by the associations is the learning moment and the reason for having a critique in class. During the critique the artist is asked to be silent, take notes, and answer only technical questions. The last part of the critique is reflection. I ask the artist to reflect on what they have learned, the meaning the class/community perceived, and the relationship between their intention and the perception of the class. The artist is asked if there is anything they might change now that they have heard our discussion.

The process of critique can be inclusive rather than divisive— descriptive rather than prescriptive. Critical thought can help us get to creative thought, art. A postmodern model posits the use of imagination to explore and invent alternate existences. Dialogue can help us make connections to others—to learn through interaction, to develop meaning. Critique can be a way of learning and becoming for the group. Students construct meaning as a group, forming a community of peers, learning from the successes and failures of their peers rather than depending on the singular “truth” of an authority. Postmodern thinkers are skeptical that theory can model reality—they resist prescription. They stress that truth and knowledge are constructed by individuals and groups, that truth and knowledge are mediated by language and culture. They accept the limitations of multiple views and the indeterminacy on our interactions. They believe that language, culture, and society are arbitrary and conventionally agreed upon—not natural— and promote the use of historical strategies to show the interdependence of consciousness, signs, and society. The theorists seek to identify multiple forms of power and domination through advocating a form of radical democracy, giving voice to all, hearing each individual.

This critique format is not unusual; what is different is allowing the voices of peers to dominate the discussion. Interpretation is a communal endeavor and a community is ultimately self-corrective. The organization, the formal structure of this critique, can seem awkward at first but only if we are seduced by the controlling organization of conventional communication to believe in the “natural” lilt of the critic. Even though the professor has more experience critiquing art when his or her voice dominates the discussion, the students do not build confidence in their ability to construct meaning, interpret, or analyze the visual world. The use of formalized dialogue helps develop constructive interactions that promote critical and creative thinking as individuals and as groups. Once used and practiced it becomes as transparent as our seemingly neutral conventional interactions. This benefits society by modeling direct participation in engaging critical matters of culture.

When I feel my points or ideas have not been voiced during the critique, and because as a professor I must assign grades, I use individual critique sheets to convey information. The lesson for students during the critique is that their voice and experience in interpreting images are sound and valuable. The students work as a community of peers to construct meaning without the search for universal truth. They learn to be self-reliant and work without the guidance of authoritarian leadership. They engage the world of images as independent critical thinkers and trust that their community of peers will be a self-correcting group. This is a model for democratic behavior which is easily integrated with their development as artists and may be unique in their experience of education.

George DeWolfe

Rochester Institute of Technology, NY

It has been my belief and practice for some years to teach visual awareness as a skill. Visual awareness is the coupling of perceptual skills in the basic elements of seeing with the practice of awareness skills. Although highly involved in theory, the practice of visual awareness is reduced, in the end, to skill in practicing it. Learning about visual awareness through the information available on visual perception and awareness is easy. For a teacher, however, developing the skills for teaching these things is bought only with blood, wisdom, and extensive knowledge of human character. There are three aspects necessary for visual awareness: Wholeness, Authentic Response, and Presence.

Wholeness is the artist's desire to work from a place and expression that gives a feeling of “oneness” with the world and oneself. It is expulsion from oneself of the concept, context, content, and culture overlays that are the blocks to visual awareness. The skills are Acceptance and Mindfulness.

Authentic Response is seeing out of oneself. Authenticity is different from originality. Originality is simply seeing something that is different. Authenticity is seeing from oneself. Finding skills in this area, to bring out oneself, is the hardest exercise a teacher can perform. The skills take the form of riddles and exercises that have no rational answer. The answer to the riddles is only authentic response.

Presence is the capturing of the wholeness felt and is the authentic response made visible through an image and a print. Presence is taught by the craft, overlaid with feeling and emotion. It is the easiest aspect to develop skill for, because it remains largely technical in nature, in manipulating both the image and the print. The skills are the craft of the print, either traditional or digital.

David Page

Duke University, NC

Teaching is NOT about the teacher. It is about imparting knowledge, enthusiasm, and confidence to the student. It is all about the student. That is a lesson I learned from a cadre of abundantly caring photography teachers as a student in the early 1960s.

The common misconception, that knowledge of subject is the key to teaching, pervades the education field. Of equal if not more importance is enthusiasm for the subject and the ability and a strong desire to share knowledge. Many a fine photographer has been poorly skilled as a communicator, or worse yet demands that the student learn the only techniques and practices that have served the teacher well.

Most of my students at Duke were taking a Photography class as an arts adventure or to have a hands-on visual experience in the midst of their strenuous other academic challenges. They were often surprised that “Introduction to Photography” was not an “easy” course. Most broadened their education by learning a new visual language.

Teaching at a Community College was most challenging and rewarding. There is a broad mix of students with a varied life experiences, levels of commitment, and expectations. In a Community College setting diversity is the standard. The 40-year-old divorcee, the immature 18 year old, some who were only meeting their parents' expectations by “going to college” and keeping their health insurance options, and the 25 year old ready to start his adult career would all be in the same class. The older students were my more dedicated students, and most of my 18 year olds were not highly motivated academically. The older students were typically ready and eager to learn and progress. The key was to help them determine their interests and aptitude, which was often different from what they thought when came in the door. The next step was to encourage them and direct them towards their goal. Sometimes that meant sending them to another institution where their needs would be better met. Honest encouragement went a long way in helping them get the most out of their willingness to work hard, which was an attribute that most possessed.

Regardless of where you teach, find out about your students. Where does the student wish to go in life? Discover what motivates that student. Learn how to trigger the student's individual “GO” button. My most effective way to reach the undedicated student was to praise small accomplishments, to let them know that they were capable of more than they thought they could do.

It's ALL about the student…Each student, individually. The payoff is having changed each student for the better. As an educator, what better reward could there be?

Elaine O' Neil

Rochester Institute of Technology, NY

Why I Don't Give Grades

If there is any power in the combination of tenure, advanced academic rank, and age, it is the freedom to reflect on successful teaching experiences and use those highlights to inform one's teaching.

The most important influence on my teaching was my 15 years at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts—Boston. Class grades are not assigned by faculty…they teach. Rather, at the end of each semester, students make a formal presentation of all work, done in all classes, to a review board. This committee is composed of two faculty and two students who critique the presentation in an hour-and-a-half session. The quality of the work and its appropriateness as a representation of 13 weeks of effort are discussed. Before the meeting is completed, the committee decides if the student will be awarded full, partial, or no credit for the semester and a written report is submitted.

By Jodi Goldenberg, Rochester Institute of Technology, NY, student of Elaine O'Neil

Relinquishing the inherent power of grading has a profound effect on teaching. Foremost in my mind is that the teacher—student relationship is dramatically altered, and “getting an education” becomes an activity for which both teacher and student are responsible. Faculty must learn to motivate students utilizing non-punitive strategies.

Experiences in other schools have served to reinforce my belief that the Museum School model was the best way to educate artists. It is a system which fosters self-motivation, creativity, and curiosity— attributes critical for a successful career in Fine Arts, Advertising, or Photojournalism.

All students need to understand that on their first roll of film, they're capable of making images, which could add to the history of the medium. School is not a preparation for life—it is life. School is not marking time and class work is not merely practice; instead, images made for an assignment and discussed in critique become part of the visual data bank upon which new images are built.

Mastery of photographic technique is critical if a personal, powerful visual voice is to evolve, but technique can be learned through reading and practice. School provides a culture and a set of experiences through which students gain personal insight, connect to the core themes, which will inform their imagery over the course of their careers, and develop a respect for their work and the work of their peers. Further, they need critical skills and the ability to articulate the abstract ideas, which they hope to make manifest in their photographs.

Successful critiques demand a respectful atmosphere in which all ideas and opinions are seriously considered. Knowing that positional power makes my criticism perceived as definitive, I first act as the moderator of the students' discussions. Then after the students have discussed the work, I use my time to add to what has been said or to point out connections between the bodies of work on the wall.

During my eight years as an academic administrator, Deming's Total Quality Management was the style du jour. In a presentation at an AAHE (American Association for Higher Education) conference, the concept of students as managers of their education, as opposed to customers, was discussed. I present this idea to the class and point out that it is the students themselves who decide how much they will learn, what classes they need, and what of the experience is important to them on both the personal and career level. This perception of our roles makes the success of the educational experience the result of how much we all put into it. The students are surprised to be placed in a position of power, but most are ready to accept the responsibility.

Martin Spring borg

Minnesota State Colleges and Universities

Studio Arts Mentorship

As instructors, we know that we cannot be with every student all of the time. In fact, a great deal of learning takes place outside of class—during open labs, when we are not even in the building. Students learn from one another, and those students who instruct their peers, even in the most casual of ways, end up retaining techniques and concepts much better than do those students who simply “go through the motions” in the classroom.

While a faculty member at Inver Hills Community College, I wrote a grant that focused on enriching student learning through the introduction of guest lecturers and student mentorship. The desired outcome of the project was better prepared students, able to take their skill or knowledge to further levels upon graduation or transfer from Inver Hills Community College. The project took place in two main phases—with student mentorship/teaching opportunities following a visiting artist workshop series. Within the first five weeks of the first semester of the project, three visiting artists gave inspiring lectures and workshops. During lectures, they showed samples of their own work and taught some of their techniques to advanced photography students in workshops.

Once the visiting artist series was through, the advanced photography students began working with their newly acquired skills and preparing to conduct their own workshops. With my mentorship in the preparation process and under my supervision in the classroom, the advanced photography students taught the original visiting artists' techniques to beginning photography students the following semester.

These workshops along with the following mentoring and guidance went extremely well, as the advanced photography students proved to be good speakers and presented the core information. Since there is now a small overlap in my sections of beginning and advanced photography, they even get opportunities to teach new beginning photography students their craft. Beginning photography students who participated in these workshops are working with these techniques as advanced photography students today—more than a year post-project.

My aforementioned desired outcomes for this project were met, and I have been quite pleased with student teaching to date. However, to fully understand the impact that this mentorship project had on the original group of advanced photography students, one need only look at their actions post-project experience. Not wanting to stop helping each other with their work, they started a photography group that meets once a month. In this group, they discuss theoretical and technical problems within their photographic work, and they share newly acquired techniques. In forming this group, they help one another make better images and they have developed a photography community of their own.

Inga Belousa and Alnis Stakle

Daugavpils University, Latvia

Art and Spirituality

“Art is eternal; for it reveals the inner landscape, which is the soul of a human being.”

Martha Graham

Contemporary development of culture and science fosters re-evaluation of existing tendencies and introduction and development of new components in education. Photographic and art education, as branches of education, meets constitutive challenges of its conventional understanding. The main character of these challenges makes an impact not directly on form or on content of art education, but the scope of re-evaluation goes directly to mega-trends.

By Marta and Viktorija Valujeva, Daugavpils University, Latvia, students of Alnis Stakle

The issues define the interconnectedness of art and spirituality, the artistic and the spiritual aspects of contemporary photographic education, and guidelines for the emerging model of contemporary visual education.

Spirituality is a very broad and vague, general, and yet specific concept. Review of the attempts to define spirituality pictures a rather paradoxical and comprehensive reality—spirituality has been considered as a result and a process, as a form and content, as a characteristic and dimension, as an experience and expression, as practice and power, as a way and basis. These discussions are neither primarily cultural, sociological, or psychological, or epistemological, ontological, or axiological in nature. They are existential or experiential and imply a deep human quest for meaningful growth or development, a search for reconnection with an ultimate state of wholeness. We define spirit as the essential character, nature, and/or quality that constitutes the pervading or tempering principle of images.

The key aspect of spirituality within photography education is reconstruction and transformation of the understanding of being human from the Modernist to Postmodernist viewpoint that occurred in the second part of the 20th century. The understanding of spirituality now reflects postmodern thinking, rejecting supernatural dualistism and atheistic nihilism in favor of nondualistic spirituality. Such an understanding of spirituality suggests a unique perspective of education.

The relationship between art and spirituality is historical. It was nearly a century ago when Kandinsky (1912–1966) opened up a new dimension of thinking about art. He emphasized that “we have before us an age of conscious creation, and this new spirit in painting is going hand in hand with thought towards an epoch of great spirituality.” All kinds of art affect a human's spirituality. And spirituality of a human being affects the expression of one's inner landscape in art.

Guidelines for the Emerging Model of Contemporary Visual Arts Education

We propose philosophical guidelines that characterize the emerging transformative model of photography education in the current postmodern period of time. Postmodernity has introduced significant challenges to conventional understanding of visual education. The main character of these challenges makes an impact not directly on form or on content of art education, but the scope of re-evaluation goes directly to mega-trends. The recent discussion about postmodernistic tendencies emphasizes philosophical investigations in education, including art education as an essential dimension. There are some of the most significant postmodernistic tendencies that give a renewed character to contemporary art education, including its function, content, and other categories.

We argue that all art education should acknowledge the communicative function of art. This represents reaching beyond the surface level, beyond the rational discourse of objectified values that are reflected in society. Art's function here is to reach the level of personal depths, to tell our human stories and to help us to know who we are and how and what we believe. This function opens up inter-cultural and cross-cultural views, and enriches each person and the whole community of learners.

Photography education should acknowledge art as a search for meaning. When art is interrelated with spirituality, human significance, and values, it has a potential of reconstruction of experiences of the intellect, the body, and spirit to coordinate the time, place, and meaning. Its active and dialogical nature, of meaning-making process, introduces art as a form of ritual.

As a significant guideline the integrated, theme-based content and procedure of art education should be recognized. It means that the keys of visual/artistic education merge and are human concerns.

The last guideline suggests recentering of art in the community, in educators' and students' lives and experiences. Photography should be about something beyond itself, beyond being decorative and beautiful for its own sake. Art reflects the deepest insights, longings, passions, losses, and victories and is spiritually alive. These suppositions highlight that art education is not just nice but necessary; it is for the sake of our well-being and survival.

Recognition of the interconnection of the artistic and the spiritual categories is the main constitutive aspect of contemporary imaging education. As a new model of contemporary art education emerges, it reflects the values of postmodernity. Communicative function of art, art as a search for meaning, integrated content and procedure, recentering of art in the community—all are the suggested guidelines of a transformative model of contemporary art education. Visual artistic education in the current epoch meets the tendencies of postmodernity by celebrating the self-conscious individual; merging form and content with their effect on time remains an experienced phenomenon.

Ralph Masullo

Briarcliffe College, NY

Learning to Teach

If you told me twenty years ago that I would be teaching today I would have had a good laugh and would have said that you were crazy, but after spending twenty-one years in a career as a commercial photographer, I did in fact become a teacher, to the surprise of many. So my story is about making the transition from photographer to photography instructor, which has become a truly enriching experience for me.

I have always had a passion for photography. It started as a hobby at a young age, followed by a formal education at The School of Visual Arts and then a successful career as a commercial still life photographer in New York City. After the events of 9/11, for both personal and business reasons, a need was felt to take my photographic passion in new directions. Looking for other opportunities, an ad was answered in the Photo District News. It was for faculty and a studio manager for a new photography program. Neither position seemed appropriate for my level of experience and background but I decide to apply by stating my desire to explore something new.

Brooks Institute of Photography had partnered with Briarcliffe College to set up a new digital photography program. Part of the position was training at Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara, California, and with much excitement I decided to accept the challenge. The arrangement was for a full eight-week session to train, sitting in on classes to learn their methods of delivery to become familiar with the curriculum. My experience there was absolutely wonderful; it proved to be enlightening both intellectually and spiritually, and taught me much more than I could have imagined. Attending various classes enabled me to view various teaching methods and course content, and it stressed the importance of technical skills as well as the creative. It was also quite rigorous and demanding—a good preparation for working in the industry. These are principles that are very important for students to learn and I incorporate them into every class I teach.

Being there also afforded me a unique lesson; I was given a very valuable opportunity to see through the eyes of a student. Attending class with the students allowed for a glimpse of their perspective, what they struggled with, and what excited them. This was the most valuable lesson for anyone preparing to teach photography; you must excite students about photography to inspire them and the rest will follow. After this experience I returned excited and confident about starting to teach my own classes, because the Provost and faculty members who served as my mentors unselfishly answered all my questions while sharing their knowledge and experience about teaching.

It would be easy for anyone reading this to wonder how a self-employed photographer with no teaching experience could be transformed into a teacher in eight short weeks, but my experience as a studio photographer was very similar to teaching. I was accustomed to being a mentor, establishing guidelines and rules, training new up-and-coming talent, and of course listening to myself speak. But more importantly, my desire to continue to improve my skills was extremely important. Being a good teacher means always being a good student. Teaching digital photography requires keeping abreast of the rapidly changing technology; but it goes beyond that.

For me, keeping an attitude of always looking to learn from my peers and my students themselves is vital. I have found that every group of students can be different. This requires flexibility on my part, with both the content and methods I use, to keep that level of excitement present in class. The best lesson learned is that students' excitement is my excitement and their inspiration is my inspiration; both as a teacher and a photographer, this is what makes for a successful learning experience. I have found teaching extremely fulfilling, but more importantly, that being able to share my skills and knowledge with others and being able to see a successful result is most rewarding.

Peter Glendinning

Michigan State University, MI

When learning sculpture in the form of bronze casting, students come to the class with very few preconceived notions about what the breadth and depth of the technical, compositional, and conceptual aspects of the medium are. The “rules” for good bronze castings have not been a part of the everyday experience of their lives, something witnessed since early childhood. They have undoubtedly never seen a news report illustrated by a bronze casting, or a liquor advertisement. They certainly have not tried to prove their identity to a state police officer by offering them a bronze casting bust of their own head as their proof.

Of course, in the real world that photography students occupy and come from, it is the photograph that is used to illustrate news, advertise liquor, and prove identity, along with so many other pedestrian, commercial, and even artistic purposes. As a teacher of photography, I find that one of my first jobs is to help my students understand the “rules” for good photography that they have already learned throughout their lifetimes.

Hold the camera steady. Move in close to your subject. Grass, trees, sky, and water make good backgrounds for your pictures. Such rules for composition, camerawork, and content are already firmly implanted when the students in a first course in photography walk through the classroom door. While they know many rules for good photography, they must also learn that the rules define the ultimate result and will either expand or contract their ability to create personal and unique expressions.

Unlike his or her peer in Bronze Casting 101, the new photography student must not only learn the chosen medium, but also unlearn it as well. Whether the initial technical challenges relate to the traditional black and white film/print darkroom experience, or color slide, or digital imaging, the problem is the same for the student: learning how to think and create like a photographer, untrammeled by the years of learning the “rules” of photography through the thousands upon thousands of photographs they have seen every day of their lives. This is a very difficult task for the student, and the teacher.

Just as law students attend law school to learn to think like a lawyer, then spend their remaining years in the world of lawyering learning what it actually means to BE a lawyer, so too do photography students learn to think like a photographer…then spend the rest of their career in the medium learning what it actually means to BE a photographer. When new photographers learn that the rules they choose to follow will inevitably determine the content of their pictures, and learn to imagine new rules appropriate for use if they have unique perspectives to share, they start on the path to a personal vision and expression through photography. They learn to think like photographers.

If, as a teacher, I can create assignments and responses to assignments which help students overcome their preconceived notion of the scope of the medium of photography, and help them learn that there are both ways to think about imaging that are uniquely photographic and opportunities to define rules to achieve personal expressive goals that are different from those ever seen before, then I may have been successful. Whether the students will take the lessons learned about how to think like a photographer and then apply themselves after graduation to the hard work of actually being a photographer is always an open question. For some, like some who attend law school, the intellectual exercise of learning to think like a photographer, or a lawyer, is in itself the reward…and they make their careers in other ways. For others, the real work of defining new ways of seeing, and imaging that vision, is what begins after graduation and continues throughout their lives—a constant reworking, redefining, and renewing of “rules.”

M.K. Foltz

Ringling School of Art and Design, FL

The Importance of a Global World-View for Educators in Photography

Many people in the U.S. today, after 9/11, have reservations about international travel. This is unfortunate, since travel to other countries and continents can offer a remarkable degree of personal and professional enrichment. This became especially clear to me during three residencies in Eastern and Central Europe and the Baltics under the sponsorship of the U.S. Fulbright Commission, in Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Lithuania.

As the world becomes increasingly hardwired, our visual community can no longer be defined as local or national. Living abroad or extended travel overseas is an important asset in helping us realize both the possibilities and limits of the new global village. For example, recently in Vilnius, Lithuania, I participated in the annual graduate student reviews. While there were many similarities and differences with the way we do things in America, I was especially struck by how the Vilnius Academy of Art maintained the tradition of inviting department heads from each department to participate in formal reviews across all fifteen disciplines. In addition, each faculty member submitted written evaluations that were then given to the student. A number of Lithuanian photography and media students had studied for a semester in England and Western Europe, and they all remarked how this kind of comprehensive and interdisciplinary feedback was nonexistent there, and that VAA's interdisciplinary model of instruction seemed to them far more instructive and growth-prompting. In addition, I found that it was the norm not just at VAA, but also in higher education throughout Lithuania. I was reminded of my own graduate school critiques at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where a communitarian model had long ago been integrated, but this model is becoming rare indeed in the United States.

Britten, Texas; by Beau Blackburn, Ringling School of Art and Design, FL, student of M.K. Foltz

I asked myself why. Is the answer connected with the American expectation of increased leisure time? Can “glasnost” (the opening of a formerly closed society) and recent geopolitical events give us the opportunity to assimilate new ideas into higher ed at home? Isn't integration of once-foreign ideas what has allowed our culture to renew itself? Heightened nationalism since post-9/11 has threatened to greatly reduce this possibility of internationalizing our colleges and universities. The communitarian model is rather time intensive: it can take days and require several weeks to complete the reviews, depending on the number of departments involved, but the experience can be richly rewarding for all who participate. The Lithuanian photography and media students received valuable feedback on how to strengthen their cross-disciplinary concepts—actually, a preview of what will be expected in the workplace—reaching across one's own familiar, disciplinary mindset and customs to others that may be quite different, in order to effectively and powerfully communicate using images. In the United States, departments are often self-contained towers or “silos” forcing the more mature student to negotiate the prerequisites or enrollment caps for courses outside of their major. As a result, a good deal of effort is required to gain the thoughtful response of highly qualified faculty from outside one's own discipline.

I'd like to suggest, then, that educators consider adapting the communitarian model: invite faculty from other departments, not just department heads, and rotate invitations within the department each year, so that every faculty member at some point participates in contributing their expertise. Moving to a more time-intensive review session could be built into the semester calendar, so that the traditional finals-portfolio week could begin a week earlier and be reserved for reflecting on the conceptual development of each student and on valuable feedback contributed by a broader audience of experienced professionals.

We are familiar with the coarser kinds of ethnocentrism and national chauvinism and reject them instinctively and easily. But there are subtler forms of cultural arrogance that are perhaps just as dangerous. One of those is the belief, or rather the prejudice, that because the arts are felt to be somehow more advanced or modern or sophisticated at home, the arts in other parts of the world are therefore in some way “backward” or “behind the times.” This one example, my experience in Lithuania, which I have chosen out of many possible instances, was alone sufficient to teach me that we have much to learn from other cultural and educational ractices.

Elizabeth Fergus-Jean

Columbus College of Art and Design, OH

My focus is within the emerging field of interdisciplinary studies, primarily combining the visual idiom as experienced in media and the fine arts, and cultural studies, including theory, narrative, and mythology. I believe that such collaboration across disciplines uniquely addresses the learning needs and requirements of students today. By extension, this necessitates developing curricula that speak to content integration with a cross-cultural perspective, and the application of such material within the context of our increasingly pluralistic and global community. Thus, my pedagogical approach underscores such dynamic interrelationships rather than focusing on discrete academic disciplines.

Cross-referential methodologies provide students with skills to apply their knowledge and talents in a multitude of ways. In addition, when students communicate their integrated intellectual understanding of course content in written, oral, and artistic form, it provides them with different ways to engage with the material, and helps to create connections within a variety of disciplines.

An important aspect of my curriculum design and teaching style begins with the development of critical thinking skills, coupled with the application of these skills to the subject at hand. This includes providing students with an understanding of the multivalent aspects of visuality and the language of image, and of the layers of bias projected onto images by the viewer. Each encounter with an image, whether it is seen as word/text, object, or sensate entity, can be understood through multiple layers of acquired and inherited biases by the viewer. These accretions form a perceptual distortion or lens that mediates relationships to the archetypal, cultural, ancestral, and personal perspectives. Therefore, understanding any form of image must include recognition of the lens through which we perceive such images. This process of understanding involves reflective analysis of the student's own personal and cultural bias. It further reveals the effect such perspectives have on the work students make, ways in which they perceive others, and the culture in which they live.

For example, in the Media Studies department I teach a course for photographers titled “Personal Mythology.” In this course I use an archetypal and depth psychological approach to explain how artists can understand the work they create and their place within contemporary culture. Included is an examination of narrative within a variety of media, including advertising, films, music videos, reality TV, and sit-coms. An essential aspect of this course is the relationship between the students' personal narratives and these various cultural narratives.

I focus on the students' personal stories and artistic development, and also examine their use of narrative through the study of myths, fairy tales, archetypal imagery, and the aesthetic traditions of the fine arts. Through a variety of assignments students learn ways to recognize the archetypal roots of their own stories, as well as those occurring in culture today.

To help the students begin to learn about their own personal story, I have created a worksheet and accompanying diagram that helps them recognize their filters of perception. The diagram I have created maps four layers of perceptual bias within each individual. This diagram is based on a concept of psychoanalyst Carl Jung. To paraphrase Jung, “What we consciously believe to be our personal mythology, is our interpretation and assimilation of family, cultural, and archetypal stories transmitted in mythic patterns and deeply embedded rituals stored in the body and mind.”

Through retrospection, students fill in the diagram, resulting in the perceived recognition of their lens. Important to this discussion are the levels of conscious and unconscious recognition, and possible schemata in which to pierce the veil separating the two. Once the students begin to recognize their perceptual lens, I encourage them to start trying to detect the lens of others, such as the authorial voice of text and media images from advertising, film, and TV. Beginning to understand their own lens in relationship to experiences with others helps them understand the dynamics between their inner and outer environments.

To help the students find some of the predominant cultural stories, I use an assignment that requires them to pay particular attention to concepts or images that they find everywhere within media. These concepts and images reflect the current cultural narratives that are alive within our psyches. Important to our discussion of these images is how the cultural stories impact one's personal story. I would like to add that in class I stress the importance of intuitive and poetic knowing. Being elusive to tests and measurements, this form of knowing is often not valued in our technologically focused schools or work environments.

Ralph Hattersley

Rochester Institute of Photography, NY

Notes for the Faculty of the Department of Photography

- I am quite fascinated with students, as individuals and in groups.

- I am aware of the fact that whatever it is I teach students derives very directly from the kind of person I am rather than from what I happen to know about photography.

- Most of my class sessions are student-centered rather than subject-centered.

- I measure my teaching effectiveness intuitively. When I feel strong cross-stimulational currents among the students and between students and myself, I believe that mental and emotional growth is happening.

- One must be very careful in what he teaches a student. The strongest barriers between a student and new learning are all too often the things he has already learned.

- The relationship between seeing and believing is not as simple as one might think.

- Some of the most important things a teacher does for a student are asking him good questions, stimulating his curiosity, and showing him a wide world.

- Listening is a difficult art, and there are many rewards for those who learn it.

- All pictures make some kind of sense or other, including those which seem to make no sense at all.

- To interest people in pictures we must employ the unique; to communicate to them through pictures we must employ the familiar.