11

Spiral Dynamics PLUS Supplementary Technologies

Introduction

In this chapter, various technologies that are complementary to humanity's Master Code are presented. YELLOW and TURQUOISE codes are both “being” systems. Where the YELLOW code is a chaotic organism forged by differences and change, TURQUOISE is an elegant, balanced system of interlocking forces.

New codes are formed as new life conditions emerge. We cannot deny that the life conditions that confront humanity today are more challenging and dangerous than those of any previous moment in time. We are faced with mind-blowing choices, Beck explains, and in a 2002 interview with Jessica Roemischer of What is Enlightenment? magazine, he continues: “… everything from shaping natural habitats to gene splicing to using science in various ways to alter the human experience. I don't think any of us realize yet what that's going to mean. As a species, we never had this capacity before.” He further reasons that power in the form of nuclear weaponry developed in a more complex ORANGE code, which has the stabilizing influence of the previous BLUE code in it, is now under control of a RED code that has no BLUE influence, discipline and accountability, no sense of the potential for mutual destruction that emerged in ORANGE along with that particular technological development. RED has a short time frame and power, and that poses a real threat to global peace. The North Korean situation presents us with a risk like this.

It is one of the primary risks that we face as a species.

In this chapter, an array of supporting, complementary technologies that, due to underlying congruence in philosophy, can be applied by PLUS Spiral Dynamics in the intervention phase of a transformational process, are presented. It should be noted that the links between supplementary technologies that are made here describe the unique approach that Beck crafted out over the years. In the various cases presented in this book the reader can find evidence of the practical application of, and integral approach to, transformational attempts, through the interweaving of the different technologies described here.

Adizes

Adizes and Spiral

The Adizes methodology and the body of knowledge are closely aligned with the views of Dr Don Beck on natural design. Over the years, integration increased between Spiral Dynamics and the work of Ichak Adizes. A very symbiotic relationship was formed, that led to the co-facilitation of various PhD programs at the Adizes Business School, and the integration of SD into the PhD curriculum of the institute.

Adizes Components

The body of knowledge called Adizes is composed of four parts: a model, a method, an ethic and a language. Further to this is an Adizes Professional Practice. Conceptually these parts are different, but, in reality, they form a unified and highly-integrated body of knowledge and practice.

The intent at this stage is not to describe the Adizes components in detail, but to present a synthetic view that complements the functional Spiral Dynamic YELLOW decision-makers.

Organizations as Organicism

The root metaphor of organicism is a living organism. It is synthetic because it sees entities as a whole, and it is integrative because it takes a gestalt vision of events. For Adizes, organizations are living systems with conscience and consciousness; as such, Adizes's model comprised the following:

- A human-inspired model of organizations

- A method to treat organizations as one would treat a person

- A humanistic ethics (Selznick 2008)

- A language.

Of the four world hypotheses, organicism is the one that presents the highest level of integration. It is critical to remember that the most important message from a metaphor relates to the behavior, not the entity (Morgan 1997).

Adizes Corporate Life Cycle

Organizations are born, grow, mature, age and eventually die. In other words, organizations have a life cycle with predicted characteristics. These cycles can be divided into two categories: growing and ageing. As people, organizations hold values, and as living, cultural beings, organizations have a language. In Figure 11.1 the Adizes life cycle is displayed.

Figure 11.1 Adizes' corporate life cycles. Adizes (2000)

It is clear from Figure 11.1 that, over time, as an organization ages, control increases to the detriment of flexibility, resulting in an internal focus that is crucial. Very much like the Sigmund Curve, and the Leadership Equation of Beck, the graph warns leaders to be aware of the life conditions in their social spaces both externally and internally.

For Adizes, the world has a Heraclitean nature, as an ever-changing reality. He views change as a source of both opportunities and threats. Organizations, like other living organisms, are in a continuous autopoietic (self-creative) process of perceiving and adapting to world changes for survival and development (Varela et al. 1974).

Bearing in mind change, when the sub-systems do not change in synchronicity, it generates disintegration. The challenge for organizations and for all living organisms is to be able to change while remaining integrated. For that reason, integration is the key value and leitmotiv of the Adizes Method.

The method views organizations as people-like entities, living at a higher level of being. In order to function in the short and long term, they need energy and must perform four basic functions: produce, administer, innovate and integrate (Adizes 1970).

In order to adapt to external change, organizations need to decide on internal changes and implement them. For Adizes, the process and factors required for decision-making are different and opposed to those required for implementation.

Four Sources of Internal Conflict

Adizes sees four sources of internal conflict (three original ones and one suggested by Valdesuso, based on Beck and Cowan (1996)):

- Different Managerial Styles – PAEI

- Different Interests – CAPI

- Different Perceptions – Is, Should, Want

- Different Values – Spiral Dynamics.

Each of the above-mentioned is briefly discussed below.

PAEI

The success of an organization can be predicted by the “Success Formula.” For Adizes, success is a function of the amount of energy an organization spends on internal issues as opposed to external change. Since the availability of energy is limited, the larger the amount of energy spent internally, the less energy is left to deal with external opportunities and threats.

Internal conflicts consume organizational energy. As with all organic systems, organizational energy is first focused on keeping integrity instead of dealing with external challenges, the homeostatic principle. Therefore, because of the energy drain, it is an issue of survival to avoid destructive internal conflicts. The PAEI shifts over the organizational life cycle.

CAPI

For decision-making, one needs a complementary team. For implementation, one needs to coalesce what Adizes calls CAPI, the Cooperation of people with Authority, Power and Influence. John Anderson (cited in MacIntyre 1991) said that “it is through conflict and sometimes only through conflict that we learn what our ends and purposes are.” CAPI is presented in Figure 11.2.

Figure 11.2 Coalesced Authority Power and Influence – CAPI.

Different Perceptions

Notice that the conflicts arise from different styles, different interests, different perceptions and different values, thus raising a central Divergent Problem (Schumacher 1977) between the need for differences in dealing with change and the internal cost of having differences in terms of energy-consuming conflicts. In summary, every organism and organization faces a central divergent problem between Change × Integration.

Spiral Dynamics

Although Spiral Dynamics forms an integral part of the Adizes methodology, it is not described here as the topic is dealt with in detail later. Adizes (1999) assumes that we are all “mismanagers” and thus, for an organization to be well managed, there is a need for complementary teams. Therefore, it requires and adopts a participative management style which, by itself, requires a common “language.” Participative management requires those responsible for the execution to participate in the decision-making (Aubrey and Cohen 1995). Understanding how to deal with workers, and people with different SD is crucial.

The Adizes Method

Rather than focusing on content, the Adizes Method focuses on form. Consensus on procedures creates an environment in which conflicts are more easily resolved (Selznick 2008). A structured process provides the form for developing knowledge and wisdom (Aubrey and Cohen 1995). Underpinning the Adizes Method is an Adizes Basic Equation (ABE) which reads: “Mission should be reflected in the Structure; both should be reflected in the Information Systems, and all three should be reflected in the Rewards System.”

In other words, the four sub-systems should be integrated through alignment. Since there is continuous change, Adizes explains that the ABE components rarely change in synchrony, causing disintegration, and disintegration is the source of all problems

The Adizes Method Ethics

The Adizes Method adopts the position that ethics involves working for an organization's present and future welfare, and not for the individuals, even if they are the owners. Since the model sees organizations as living organisms, and since living is being integrated and dying being disintegrated, integration, not elimination, of diversity becomes the number one value. All problems are manifestations of the lack of integration; if there is a problem, one should immediately seek the point of disintegration. This is where the insights provided by Spiral Dynamics can prove beneficial.

All other Adizes values and virtues, namely Respect, Trust, Tolerance and Patience, support integration. Integration is so important to organic entities that the energy is first directed to maintaining internal and physical integrity.

Each Spiral Dynamic value system holds different views on respect, trust, tolerance and patience. In order to create organizational integration or inclusivity, as Viljoen (2015) describes it, all the different worlds should come together in an integral tapestry.

Adizes highlighted that when facing conflict between personal convictions and the ethics of a profession or office, one must favour the ethics of one's role. The issue is not only whose ethics should prevail, but the true ethics for the organization or profession involved.

New ways to look at the world require new languages (Seely and Duguid 2000). According to Rorty (cited in Tsoukas 2005), a new vocabulary is a tool for constructing a new vision that has not been seen before. A language permits collective forms of action. One must be aware of the role of both our own vocabulary and that of others. Language not only describes, but also interprets, the world (Tsoukas 2005).

A common language facilitates communication and understanding that in turn facilitate the achievement of change. The language of Spiral Dynamics has different value systems holding different body language positions (Laubscher 2013). Silence, physical space and mannerisms are often used consciously or unconsciously; and are impacted by diversity of thought.

Conclusion

The key conclusion is that the four Adizes components arise from the root metaphor of organizations as living beings; the organicism root metaphor (Pepper 1942) is synthetic and integrative, thus privileging, like no other metaphor, the wholeness of the entities (organizations) and events (gestalt). To really understand Adizes, one must understand that all the components are based on the humanism root metaphor and that integration is its key value, that is, the state of being that allows an organization to survive and flourish.

Simple Vital Signs and Vital Signs Monitors (VSMs)

Your organization, social movement or government needs feedback to understand where its culture is, as Thomas Q. Johns explains in this section that he authored on Vital Signs Monitors (VSMs). This feedback is necessary because if you are going to move forward you must understand where you are. Every organization becomes an organism as a whole, but unlike natural organisms, the organization must build the systems for it to hear itself. The systems serve to help it see where it is in terms of the environment or superordinate goal. This is a system that lets the head know where the feet are. This often results in reflexive feedback loops where the subject becomes the object and the object becomes the subject.

The creation of Vital Signs Monitors to monitor the health of your organization or constituency is recommended. One needs to understand the phase of change in which the community is, as well as the prevailing life conditions. This isn't necessarily a complex system, but you need a way to quantify and observe the flow of world views in your constituency. This can be as basic as a survey or as advanced as a neural network scanning system. The important thing is to have data that help you understand the kind of message to which your group is receptive. Helping you in creating a policy that aligns with the way in which a value system feels safe, but without stoking the dark sides of that value system. Essentially this means looking at the needs of that value system.

Vital signs of an organization capture the culture where it is, and allow predictive inferences about where it is going. These vital signs can be captured manually through the use of polls, or they can be automated. Vital signs may be Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that help you meet strategic goals, or they may be systems that measure where your culture is. Regardless, they should inform you of what your life conditions are and the response of cultures to them. They should cut through the noise. There is a deluge of information now, but much of it is not conducive to making decisions.

- Understand your superordinate goal, and then understand how you or your organization relate to it. This should not necessarily be a top-down process, but must include the whole organization.

- Find statistics that directly influence your superordinate goal, and that can be influenced by you or the team. Many companies have KPIs for the sake of having KPIs but, as Deming (1994) said, “Management by results is like driving a car by looking in the rearview mirror.” The organization may begin to look to just meeting those KPIs. For example, a company has a directive that salesmen must have three meetings per month. This may become a problem as salesmen may start focusing on meetings instead of making sales.

- Make these statistics easily available. Almost to the point of being present at all times, similar to a Vital Signs Monitor in a hospital.

- Act on them.

Figure 11.3 shows the Vital Signs Monitor (VSM) that is in the process of being built, which aims to automatically capture the value systems of people as they use social media. The goal is to give an idea to the organization on how they should motivate a population and alert leadership of early warning signs in the system.

Figure 11.3 Vital Signs Monitor. (Johns 2017)

Assimilation Contrast Effect (VACE)

Introduction

It is widely accepted in psychology that as soon as the human mind has adopted a view or opinion it will integrate all other things to support and agree with it. This constructivist nature of the psyche results in the assimilation contrast effect that will be described in this section.

Lisa Rosenbaum (2017) highlighted the power of narratives in the cementing of a certain belief. When the context stimulus and target stimulus have similar or close characteristics, assimilation is more likely. However, depending on how we categorize information, contrast effects can also occur. The more extreme the context stimuli are in comparison with the target simulation, the higher the propensity of contrast effects.

Leon Festinger already in 1954 explained that individuals would value their own opinions and abilities by comparing them to others in order to define self. This argument forms the basis of social comparison theory. Muzafer Sherif was a founder of modern social psychology. He especially focused on understanding social processes, social norms and social conflict. Beck was largely impacted by the work of Sherif, and ultimately completed his PhD in social psychology.

The Experiment

Sherif developed realistic conflict theory that describes inner group conflict and negative stereotypes as groups which compete for desired resources. He validated this theory with the Robbers Cave experiment. This experiment involved 22 white, eleven-year-old boys with above average intelligence and school performance in the fifth grade. Further, they came from two-parent protestant backgrounds and were sent to a special remote summer camp in Oklahoma, Robbers Cave State Park, far away from home to reduce the influence of external factors. They were assessed to be psychologically normal, and did not know each other before the camp.

Researchers also adopted the role of counsellors and divided the participants into two groups. They were assigned cabins far from one another. Initially the groups did not know about each other, and group cohesion formed through involvement in various outdoor activities. They even had to create group identity by choosing a group name and similar shirts and flags. Group norms developed, and a leadership structure emerged in both groups. Prejudice started to develop between the groups – initially it manifested only verbally in the form of taunting and name-calling, but as the competition deepened, the prejudice became more direct. One group, for example, burned the other group's flag.

The tension built up to a level of aggression that was so strong that the researchers had to physically intervene. A two-day cooling-off period was allowed, and team members were asked to list characteristics of the two teams. One group of boys presented themselves as highly favorable and the other group as extremely negative. Attempts after this by the researchers to reduce the prejudice between the groups of boys simply made matters worse.

Only forcing groups together to reach common goals eased the tension among them. Sherif described the goals that can reduce prejudice significantly during the integration phase of conflicting groups as superordinate goals. He defined superordinate goals as goals that require the cooperation of two or more people or groups to achieve, which usually results in rewards to all the opposing groups.

Application

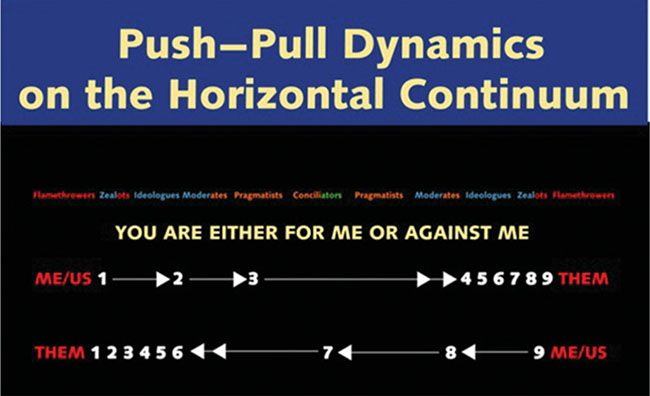

Beck applied the VACE effect three times in South Africa to directly impact the racial dynamics at play during Apartheid. It was also used in Palestine/Israel. The South African Case and the Palestine/Israel case are presented in Chapter 5 and Chapter 6 respectively. Beck and Cowan (1996) explain the assimilation contrast effect in detail in the article on terrorism. This article is available at https://goo.gl/L1nYa2. In Figure 11.4, various permutations of how we assimilate and then contrast the Me/Us versus the Them are visually displayed.

Figure 11.4 Push–pull dynamics on the horizontal continuum.

In the first continuum of Figure 11.4, due to different horizontal windows, not everyone will be able to separate the different shades, grades or degrees of diversity of thought. Two kinds of distortions happen. First, if a position on the scale is close to a person's own position, then the individual may deny differences, and assimilate the position as equivalent to his or her own.

Under other conditions, a person will push the other position away from his or her own, thus shoving it further into the camp of the “enemy”. You may then think we are similar, but I conclude that you are one of them. This is known as the contrast effect as can be seen in the second continuum. From the other pole, the direction of the contrast change, a parcel of extreme thinking is created on the opposite pole.

There is also a vertical continuum to apply as part of complex thinking systems. This continuum can be seen in the assimilation-contrast effect where value system codes are applied, as described in Figure 11.5. A spectrum of beliefs and actions result in six degrees of intensity, as shown in the Figure.

Figure 11.5 Spectrums of beliefs and actions – six degrees of intensity.

In Figure 11.5 a lens of Spiral Dynamics is superimposed on the spectrum of intensity of beliefs to display the impact and complexity of the various horizontal and vertical lenses in a society.

In the VACE:

In assimilation, a person will deny or ignore differences between their own preferred position and pull other positions into an acceptance zone. This is a form of distortion that leads to agreement.

OR

In contrast, a person will displace other contrasting positions, and push them further away than they actually are. Both extreme ranges will contrast the middle views into a camp of the enemy. This causes the middle to vanish as polarization into only two camps begins to form. Us versus Them sets in and serious conflict is generated.

In Figure 11.6 different VMEME Codes for different spectrums are presented.

Figure 11.6 VMEME Codes for different spectrums.

It is clear from Figure 11.6 that, without a superordinate goal that binds together the different VMEMEtic Codes, a social system like this will forever be troubled by fundamentalism, polarization and conflict. A new goal that can provide social cohesion is essential if any country wants to meet the needs of its people. Further, all the different parts and sections should be integrated, aligned so that a synergy of multiple elements, entities, interest and motives are all woven together in a healthy functional environment. We call this MeshWORKS.

MeshWORKS

A MeshWORKS is a specific project and process where differences are woven into the tapestry of a company, culture, community or society-at-large. Second-Tier leadership or MeshWEAVERS are those who see the cohesion in fragmentation; the simplicity in complexity; the order in chaos. They function more as Integral Design Engineers (IDE) rather than relying exclusively on conflict management or dialogue facilitation.

A MeshWORKS is a way of uncovering the most basic value system codes that exist between different cultures, and impact the surface level manifestations if such should be found. Various assessments are available to assess these codes on an individual level, such as the Psychological Map. On the collective level, the importance of a Vital Signs Monitor (VSM)1 becomes critical.

To create a MESH requires an understanding of the unique dynamics of each entity, as well as a synergistic impact when multiple entities are brought into some type of relationship. The term WORKS conveys the notion of practicality, coal-face, grass-roots, bottom line, where the rubber meets the road and where the talk is translated in the walk.

To be MESHED means that the following are integrated, aligned and synthesized:

an entity with its market, clients, customers, stakeholders, patrons, patients and supporters

+

an entity with various functions such as R&D, sales and marketing, accounting, production, people relationships, leadership patterns, time-lines, technology and business systems

+

an entity with diverse codes, life conditions, developmental gaps, and mixed levels of complexity.

If not MESHED it can create a MESS!

Value Engineering Applied – a Spiral Dynamics Approach

Dr Rica Viljoen

“The only thing that guarantees an open-ended collaboration among human beings is a willingness to have our beliefs and behaviors modified by the power of conversation.”

Sam Harris (n.d.)

The content of this document constitutes a chapter from the authors’ book titled Organizational Change and Development, published by Knowledge Resources, 2015.

Introduction

Value management became an essential part of operational processes in organizations in the 1980s as part of Continuous Improvement or Kaizen (![]() ).2 This is an ongoing effort to improve products, services or processes. In Japan, W. Edwards Deming (1950) taught top management representatives how to improve design, and therefore service delivery. Quality circles formed an integral part of these processes, David Hutchins (2008) postulates. Various versions of this process are still found today in manufacturing businesses such as Green Circles in Interstate Bus Lines, Quality Circles in Toyota South Africa and PDSA test cycles in health care.

).2 This is an ongoing effort to improve products, services or processes. In Japan, W. Edwards Deming (1950) taught top management representatives how to improve design, and therefore service delivery. Quality circles formed an integral part of these processes, David Hutchins (2008) postulates. Various versions of this process are still found today in manufacturing businesses such as Green Circles in Interstate Bus Lines, Quality Circles in Toyota South Africa and PDSA test cycles in health care.

Beck and van Heerden (1982) write that Japanese high-quality products have resulted in an increase in exports with subsequent friction with other countries. They describe the basic philosophy of quality-circle activities as follows:

- Contributing to the improvement of the organic structure of the company, as well as to company growth.

- Making the job site an enjoyable, and yet challenging place by paying respect to human personality.

- Demonstrating the full capacity of human beings so that potential human capability can be used unlimitedly.

In the 1980s, companies in South Africa tried desperately to implement these Japanese philosophies. For many of these companies this initiative was like most other fads: it soon faded. One of the reasons identified by Beck and van Heerden (1982) was that, unlike in Japan, 50% of South Africa's adult labor force in any given factory was illiterate. The statistical methods followed in the Japanese quality circles thus presented problems.

Loraine Laubscher (2013), who worked very closely with Keith van Heerden and Don Beck, realized that codes in Japan are very different from those in South Africa. BLUE optimization initiatives did not impact on PURPLE systems.3 A different approach was needed to ensure that different thinking systems would connect across the boundaries of diversity of thought. Value management deliberately leads a group of people through a structured, shared decision-making process where groups interplay analogue and digital thinking in achieving common understanding and inclusivity. This became known as human mandalas – Value Circles for inclusivity.

In this part of the chapter, the value engineering applied through the integration of Spiral Dynamics is presented. Various cases of where this approach was applied are shared in the form of short cases.

Value Engineering

The first time the term “value engineering” was heard, according to Beck and van Heerden (1982), was when he was employed at the Virginia Gold Mine, in 1963, in South Africa. A work study group was set up that integrated thinking from Edward de Bono and Edwards Deming. Van Heerden was also influenced by Larry Miles and the work done in the General Electric Corporation after the Second World War. Van Heerden later received various accolades from the Society of American Value Engineers – in 1974, that of Certified Value Specialist, later in January 1988, the Value Specialist Life Award, and the Value Engineering Merit certificate in May 1988.

The extensive differences in religion, race, language, culture and thinking systems in South Africa made it imperative that new, effective ways of bridging diversity be developed as a matter of urgency in the early 1980s. South Africa is generally recognized as a microcosm of the world in one country. The key to a golden future for this country and its people was seen to lie in total commitment and dedication to action plans and policies to achieve mutually agreed and understood goals and objectives, van Heerden (n.d., p. 2) argues.

Van Heerden heard Beck speak at a conference in America in the early 1980s. It became clear to him that Don had to visit South Africa. Later, they did a lot of work together in the unstable mining sector during social uprisings in this diverse yet troubled country. The National Value Centre in South Africa was established in 1986 and Beck, van Heerden and Laubscher became the principals of this progressive, value-adding entity. The case studies in this chapter were all conducted under this entity.

Value Engineering and Value Circles

Edward Deming (2000) asserts that the blame for 85% of all faults in production procedures can be laid at the feet of management. Van Heerden (1974), continues to say that, in South Africa, the blame is invariably attributed to workers, whose opinions and feelings are not considered. The long-term sustainability of an organization, through the implementation of a culture of inclusivity, is often not the concern of management. The human energy in systems to perform is a critical element for leaders to consider. People that do not feel respected or appreciated, feel less engaged (Viljoen 2015). Engagement has direct correlations to success, as measured by business indicators (Viljoen 2014). A way of unleashing this human energy in systems is through quality circles, a method of value engineering.

A quality circle, Hutchins (1995) explains, is a volunteer group composed of workers, together with their supervisor (or team leader), who are trained to identify, analyze and solve work-related problems. The solutions on how to improve the performance of the organization are shared with management. During the process, employees are motivated. Hutchins continues (1995, p. 23): “… quality circles are an alternative to the dehumanising concept of the division of labour, where workers or individuals are treated like robots.” Different problem-solving techniques are taught to team members. These include fishbone diagrams, Pareto charts, process-mapping, graphic tools such as histograms and the pie chart, run charts, control charts, scatter plots and correlation analysis flowcharts.

Spiral Dynamics philosophy can enrich value engineering and management significantly. The workers at Litemaster developed the name Value Circles and created a logo. After being part of a circle, and experiencing its value, they were asked: “What should we call this circle?” They then drew three intersecting circles and explained that one circle was for Quality, another circle was Quantity and the last was Cost. According to them, the three together would give you Value. The concept “Value Circles” was born. In facilitating a Value Circle, the emphasis is on finding a balance between quality, quantity and cost through the inclusivity of all. In this chapter, the approach of Value Circles is positioned, a typical process is discussed and five case studies are shared.

The Process of Value Circles

Stakeholders such as customers, shareholders, unions and management have specific expectations from systems. Through a systemic process of input, transformation and output, a final output is delivered that can lead to stakeholder satisfaction. During the transformation phase of the process, support is provided by service functions such as Human Resources and Finance. The process improvements are co-created through a process of inclusivity as conceptualized in the doctoral study of Viljoen-Terblanche (2008).

Beck and van Heerden (1982) described Value Circles as a program that allowed participation and stimulated implementation of solutions. Laubscher adapted this concept to integrate different thinking systems in a holistic whole, a people mandala. Basically, Value Circles stimulate personal growth in individuals. They also facilitate an enabling shift from right-brained people to using their left brains and vice versa. In that way, it is good at harvesting latent brainpower.

During this process, the consultant alternates analogue and digital thinking activities. In such a process the consultant draws heavily on Spiral Dynamics understanding, especially PURPLE and RED. Mostly, consultants ignore how these thinking systems differ from BLUE and ORANGE world views. This results in confusion when carefully planned strategies seemingly have no impact whatsoever.

Employees appointed to solve the dilemma must be those who noticed the difficulty or who complained about it. This may be referred to as “fitness for purpose.” Observations about the attitude and behavior of people are integrated with the study of various psychological theories, management theories, the writings on thinking and an understanding of industry.

A leader, facilitator or organizational development practitioner should act as a catalyst. A catalyst maintains its own dimensions although it is inserted into and removed from the system in which it enables change.

A Typical Value Circle Process

In Table 11.1 a typical process flow of a value is discussed. The outcome of this process becomes the input for report-back meetings.

Table 11.1 People mandala process. (Laubscher 2015a)

| METHOD | QUESTIONS |

| Objective | What is your problem? What do we need to discuss? |

| Information/Function | What is happening at the moment? |

| Evaluate | Which function is the most important? |

| PARETO principle | Concentrate on the top 20% |

| Creativity | What else can we do? |

| (No judgment must be allowed at this point) | |

| Evaluation/Development | Which of these ideas can we join together to make a good plan? What will it cost? |

| Five-star rating | Which of these ideas can receive a 5-star rating? Which ideas receive 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 stars? |

| Report/Plan | Star ratings |

| Feedback/Adjustment | Solution proposed

|

Different Value Management Cases

Health Care Issues

This section was written by Ansie Prinsloo, an expert in quality in health care.

South Africa's health care industry faces the same global challenges of increased complexity of care, antimicrobial resistant organisms and budget constraints (Flott et al. 2017) and the call for concerted and effective ways to improve health care outcomes (Porter 2006).

The hospitals in which patient care is delivered are complicated, highly dynamic environments where systems failure causes patient harm and erodes value (Vincent, 2006). In South Africa, this complexity is amplified by nurse shortages, specifically in the higher skill categories, and a seemingly insatiable demand or waiting list volumes. Compensatory tactics deployed include supplementing nursing teams with lower-level health care workers or bridging lower skill categories to higher levels, adding to the multiplicity of skill and experience in an already diverse group (Gray, Vawda and Jack 2017).

Nurse management, charged with improving care within this complexity, tends to follow hierarchical, strong BLUE-driven policy and top-down governance of these diverse, multicultural and often Code PURPLE or Code RED teams. Large case volume and outcomes measures add more pressure on front-line nursing and management staff, increasingly unable to relate to one another. Overwhelmed front-line staff can be seen as apathetic by management, who, in a desperate attempt to improve engagement, turn to BLUE approaches such as audit activity, which further erodes team cohesion. To introduce change into this environment may not result in improvement and actually may make things worse for both patients and staff (Deming 1994).

Coupling improvement cycles, as explained by Deming (Langley 2009), with an appreciation and respect for different thinking patterns within the group has, however, been seen to achieve breakthroughs in these teams. Focusing on inclusive engagement, the nursing teams and management collectively analyze problems and design solutions, which facilitates a dialogue around their shared purpose.

Problems are analyzed using generic tools such as process and systems analysis as a team, with a non-punitive focus. Each learning about where or why the care system failed can be used to form a change idea by the team, based on what they predict will cause the desired improvement. The team subsequently test these changes on a small scale in their actual work environment, shifting to become co-creators of their world of work. Collectively, the outcome of the test is studied and discussed before the next test idea is chosen by the group, constantly referencing the stated aim and measures. Management adopt a facilitative role as explained in the Value Circles with a focus on consultation and communication with the team. The entire team oscillate between the scientific, left-brain aspects of improvement, such as problem analysis and measurement, to the right-brain art of improvement in generating ideas to test that will lead to the improvement. Using run charts, performance is tracked and displayed in nursing units, serving as a powerful tool to stimulate conversation about progress and celebrate successes within the team.

Where errors in patient care do creep in, teams themselves consider the numerous contributing factors that lead to the system's breakdown and generate improvement to prevent recurrence (Prinsloo 2017). Respectful consideration for the multiple cultures within the system allows the evolution of a new collective “Just Culture” (Vincent 2006), which is fundamental to patient safety improvement. This culture is not seeking punitively to blame the individual, but appreciates the entire system and the humans within it. Second-Tier thinking allows for the gifts from the different codes to be unleashed in the form of human energy in the system to perform. This will result in an increase in patient care indices and productivity (Viljoen in Martins, Martins and Viljoen 2017).

Taxi Violence in the Greater Pretoria Metropolitan Council (GPMC)

At the beginning of the new millennium, there was a huge problem with taxi conflict in Pretoria. The taxi drivers began killing each other, and setting one another's vehicles on fire. Andrew Barker was approached to facilitate a meeting between the taxi associations, the public and the authorities of the provincial government. He requested the assistance of Loraine Laubscher. The objective of the workshop was to develop an implementable plan that would result in a transformed, violence-free taxi industry within one year.

After talking to stakeholders the conclusion was reached that the business phrases that were being used were foreign to the thinking of the people in the taxi industry. A mechanism had to be identified to catalyze their understanding of the sophisticated English terminology of business.

It was well known that the people were soccer addicts. Barker and Laubscher collected as many balls as he could from different kinds of sports like soccer, rugby, tennis and so on. The next day the consultants started to toss the balls to the consultants in the GPMC boardroom where the workshop was being held. They tossed the balls back. This method was used to defuse the threatening conflict situation.

The consultants explained to the stakeholders that the balls represented games that had rules and regulations, as well as punishment for non-compliance. However, ball games were not only all about discipline, and could still be exciting and pleasurable. Laubscher proposed that the group should look at the conflict situation through the framework of a soccer game. In soccer there are also strict rules and all participants, including spectators, must understand the rules. People are in control, and every participant has a part to play in the game. Every participant also has a specific function to perform in the game. If the taxi industry could be restructured into a first-class soccer team, the violence could be eliminated. The metaphor of soccer was used to create an understanding of the complexity of the taxi industry, since soccer was something to which they could relate.

All stakeholders in the taxi industry were knowledgeable regarding the rules of the soccer game. Everyone knew what the goalkeeper was supposed to do, and the consultants were able to translate the rules of the taxi industry into an understanding of the soccer game. For instance, the goalkeeper could be the safety officer. The taxi was the playing field and the referee was the taxi inspector.

The atmosphere in the room changed dramatically when those present realized that, because they understood the game of soccer, they also could understand what to them appeared to be the complexity of business. This was magic!

After working strategically through all the identified aspects, and applying these in the proper ratio, the functions needed were identified. Parallels with soccer were drawn, and a structure for the taxi industry was built. Table 11.2 is an extract from the original report to illustrate how the roles and rules of soccer were equated to the taxi industry. The Table describes the concepts and ideas of the game of soccer, and then aligns them with the concepts and ideas of business within the taxi industry. From these, recommendations could be made on the actions and activities that were needed to achieve the goal. With the cooperation of the stakeholders the role that everyone should fulfill, and the date by which it should be implemented, could be determined.

Table 11.2 Roles and rules in the taxi industry form a Value Circle.

| Function: No Function and Recommendations Identified | |||

| Game – Soccer | Life – Taxi Industry | Recommendations | |

| Questions & Statements | Concepts & Ideas | Concepts & Ideas | Actions & Activities |

| 1 Identify the ball | Focus | Vehicles are the focus | None |

| 2 What is the game? | To win | The game is survival | None |

| 3 Who are the players? | Teams | Players are taxi owners | None |

| 4 How do you learn the game? | By playing where you want to play | By having a vehicle and using it | None |

The workshop turned out to be very successful, and the consultant submitted a report to the GPMC. Later the Department of Transport requested a copy of the report, and the entire structure of the taxi industry in Pretoria was structured according to the outcomes of this workshop.

Hostel Beds at Western Deep Levels Gold Mine

Another example of the implementation of Value Circles happened under the sponsorship of Richard (Dick) Solms, the manager of Western Deep Levels Gold Mine. Fourteen mineworkers were selected to attend the workshop to make it as inclusive as possible, with a further understanding that more participants could be chosen from the 3 000 to 4 000 low-level employees at the mine.

This group was granted the opportunity to choose anything in the miners’ hostel they would like to improve. There was agreement that all of them would like to improve the beds.

In the hostel, all beds were of the double-decker type, and the space underneath the beds had to be shared by the two occupants of the beds. The beds were studied, and it was found that three things were problematic to the users. There was no place to put a Bible (or any other book) when you went to bed. If you were a smoker, there was no place to put an ashtray. The third major difficulty was the space under the bed, because all kinds of things such as wet boots, odds and ends and even left-over food were stuffed into that space. There was also the difficulty of other people touching and interfering with personal belongings under the bed.

This revealed another difficulty. When the miners came up from underground, their boots had to be washed, and they remained wet for a long time. The hostel manager tried to solve this problem by erecting a structure of wooden poles higher than 75 cm. Miners could put their boots upside-down on these poles to dry. This worked well, except at night, because if you had new boots, chances were great that someone would steal them. Therefore the wet boots ended up under the bed. Naturally this practice was totally unacceptable.

The members of the value management group were required to come up with constructive answers to address these identified difficulties. They suggested that by welding a metal ring to the head of the bed into which an ashtray could be inserted as well as a Bible or book holder, this problem could be solved. The first two problems were therefore attended to.

The third one remained. Here the most innovative plan was to enclose the space under the bed. Alterations were made to the beds so that wet boots and jackets could be accommodated in a safe and dry space where the draught of air could dry them out.

It was clear that that PURPLE was at play with the people and that the BLUE code of management that was previously followed was unsuccessful and not sustainable.

A PURPLE approach had to be followed. A proposal was presented to the mine manager who offered to put a boilermaker at the team's disposal for the purpose of creating their own beds. However, the boilermaker was not allowed to give them any advice. So they had to build a prototype without the assistance of the boilermaker. Eventually the participants ended up with a prototype bed, and a group of very proud men who had designed a plan, rebuilt the bed and solved the problem.

This was placed on display outside the hostel manager's office where the representative of a company that supplied the mines with various types of equipment saw it. This company asked whether they could borrow the prototype, and make a bed that would be acceptable to the mine. The plan for this bed was based on the one the miners had made. So away went the prototype, and back came a painted bed that looked very smart. Management decided to place an order for these “new-type” beds to replace beds when they became obsolete.

Normally all orders are delivered to the mine stores, but these new beds were delivered direct to the hostel at 18:00. The sun was just about to set. All the senior management had already gone home. The hostel police were contacted, and were told that the new beds would be stacked on the veranda. The alternative was to send the beds back to Johannesburg, and have them returned the next day. The beds were left on the veranda, and the watchmen were requested to guard them. The hostel manager would distribute them fairly the next morning.

On arrival the next morning only the dilapidated old beds were visible on the veranda. On investigating it was found that during the night senior personnel had claimed the new beds for themselves. Juniors were ordered to take out their old beds and put them on the veranda. The group who was responsible for the newly-designed beds was not resentful, because even though senior personnel had claimed the beds, this was an approval of their design skills and an accolade to these skills.

From then on when a Value Circle was announced no one resisted. In fact they were all very keen to be considered to take part in the session that co-created real solutions and meaning.

Benefits of Value Circles

The benefits that typically manifest from a Value Circle include:

- The creation of an open environment within the company for unrestricted communication at all levels.

- By the participation of workers at all levels the company is able to fully utilize the abilities and skills of all of its human resources, and owing to their involvement, the staff are far more motivated towards effecting improvement within their areas of responsibility.

- The voice of the employees in the organization is heard and inclusivity is strengthened.

- Decision-making becomes more structured and sustainable. Creative, cost-effective decisions can now be made at all levels.

Tangible benefits to the various companies materialized in the form of increased production, staff involvement and engagement and ultimately monetary turnover. Simultaneously staff turnover decreased. Participants of these sessions reported a permanent shift of consciousness. This did not only change the way in which they functioned and worked, but also how they fulfilled their roles in their families, communities and society at large.

Carkhuff's Seven Skills

The Theory

The core of Carkhuff's work is concerned with helping people through counselling. His major contribution is the provision of a means by which one can learn how to help people who are in need of counselling. The cornerstone of his work is that one need not necessarily be a professional; a lay person may also be able to help, provided that such a person is well-versed in Carkhuff's seven dimensions for effective interpersonal facilitation. The Seven Skills of Carkhuff (1969) are described in Table 11.3.

Table 11.3 Carkhuff's Seven Skills. (Carkhuff 1969)

| Initiative Dimensions | Empathy |

Understanding The ability to understand another person's state, condition, frame of reference or point-of-view The Helpee believes “you are in my skin.” The Helper strives for an accurate sense of the other's experience “joining”. Note: before empathizing with the assumed reality on the other side; check first, then provide honest “moccasin'” feeling (moccasins = this is what I think/feel it's like to be in your shoes) |

| Respect |

Caring for Someone Responding in a way that conveys caring for the other Responding in a way that conveys a belief in their capacity to do something about their situation |

|

| Genuineness |

Being Real The Helper is being at home with themselves, here and now The Helper comes into direct personal encounter with the Helpee and responds authentically The Helper reports out their internal states (similar to “openness vs. personalness”, relates to the context of the exchange, not content) |

|

| Responsive Dimensions | Self-Disclosure |

Volunteering personal information Helper communicates an openness to volunteering personal information in accord with the Helpee's interest and concerns |

| Concreteness |

Being Specific Moving from abstractions to specifics The more concrete one is the more likely they are to connect with their experience |

|

| Confrontation |

Telling it like it is Pointing out the incongruent; discrepancy between worlds, feelings and actions An invitation to examine the behavior and change it if necessary |

|

| Immediacy |

What's happening now? Helper's ability to discuss with the Helpee what's going on between them Helper's ability to discuss with the Helpee where s/he stands in relationship to Helpee |

The Application

Carkhuff adopts a broad approach to interpersonal interactions in order to encompass all interpersonal engagements, and not only those intended as a helping interaction (see Table 11.3). The model includes three critical helping stages: exploration, understanding and action.

Skill 1

The seven-dimensional model begins with Empathy, viewed by Carkhuff as the most vital of all helping dimensions. He defines Empathy as functional, where the activities of helper and helped cannot be separated. The level at which one operates in terms of Empathy includes “sensitivity” measures ranging from Level 1, the empathic understanding of the listener or helper listener is not indicative of sensitivity to the other's feelings, to Level 5 where it is clearly visible or even tangible that the listener comprehends and acknowledges the feelings of the helped. The middle levels serve as a measure of moderate awareness, but not fully comprehending the helped. This is not for lack of sensitivity, the key element being experience or togetherness, that is, having experienced the same depths of need, or even experiencing them together, and as a result, empathizing at an advanced sensitive level. Further differentiation in Empathy levels relates to the art of listening, the level which one adopts for enabling an empathetic reaction. These dimensions are derived from, and are consistently validated against, a Scale for the Measurement of Accurate Empathy, designed by Charles Truax, in 1961.

Skill 2

The second aspect, Respect, relates to the verbal and non-verbal aspects of communication where the listener or helper exudes a positive composure towards the helped, and expresses concern for the helper's emotions, feelings and experiences. Respect also has levels, both verbal and non-verbal. The first level is indicative of little or no respect for the helped, but grows to Levels 4 and 5, which show deep concern and feeling for the plight of the helped.

Skill 3

The third dimension, Genuineness, refers to a person being “real” during an encounter, not hiding behind a façade and thereby avoiding meaningful connection between the helper and helped. Genuineness requires self-awareness, allowing the helped access to the feelings experienced by the helper. It is a direct personal encounter between people, being oneself and allowing one another to see that person. Level 1 of this dimension relates to defensiveness on the helper's part, not allowing access to the inner mechanisms, feelings and emotions experienced during the encounters. To a degree, this interaction is destructive and even hurtful. As the levels increase, so does the ease of communication between the parties, and becomes one of mutual communication and non-exploitative sharing. Negative and positive feelings are constructively expressed by both parties, increasing the depth of meaningful interaction.

The first three of Carkhuff's dimensions, Empathy, Respect and Genuineness, are necessary for effective communication during an interpersonal relationship to help people. These were initially positioned by Rogers and later expanded on by Carkhuff by providing a further four dimensions that described the skills required for responding appropriately during the interactions (Rogers 1967). In essence, the first three dimensions establish the basis of an open and honest dialogue between people, while the latter dimensions guide the helper's responses towards the helped.

Skill 4

Self-disclosure is also described by Carkhuff as spontaneous honesty between the parties involved. As more is shared, so a deeper level of understanding is reached. The initial measurement levels of Self-disclosure indicate that the helper shares little or nothing of self; interactions are at superficial levels of honesty and nothing is volunteered. The highest level, Level 5, requires trust so that one may feel at ease and share deep-rooted experiences, shame or embarrassment.

Skill 5

Concreteness is a level where all vague or ambiguous commentary is eliminated; it is about specifics and correctness, and, as a result, enhanced understanding. The first level of Concreteness involves the helper making no effort to guide the interaction toward relevant or specific communication. By its highest level, Level 5, the helper proactively facilitates direct expression of all feelings and information that are relevant in concrete terms.

Skill 6

The dimension Confrontation encourages the exploration of seemingly incongruent elements. It involves the ideation of concepts that relate to self, behaviors, insights, resources and even perception. During the initial stages these themes seem disconnected from the interaction; it is helpful to take a step backwards in order to evaluate the behavior of all the parties involved. The initial levels of this dimension involve the helper being disengaged from the helped. They include judgment, even stereotyping, and, although negative, the important point is that this dimensional level is activated. At the highest levels, the discrepancies and incongruences are identified in each other, and are immediately discussed to a point where the people involved are in tune with one another, and discussing or even confronting the tensions takes place calmly and without prejudice.

Skill 7

Immediacy is the dimension that deals with the real-time nuances sensed during an interaction, and dealing with them in the “here and now.” It describes sensing subtle changes in the communication line and internally questioning why they are occurring. It involves asking why the helped is changing the line of communication, and asking why the helped has had to do so. At Level 1, the helper disregards or even dismisses these nuances. The intermediate levels describe a tentative approach to discussing the changes, but not necessarily getting into specifics or pushing for a response. At its highest levels, any changes in the nuances of the interaction are discussed openly and honestly.

Carkhuff's model was designed to maintain the integrity of interpersonal interactions. It describes the interactions in two phases, namely, the initial engagement and the responses appropriate for facilitating the interaction. The dimensions of the model are based on Empathy, and more specifically empathic understanding. The dimensional model represents a practical and theoretically sound perspective that can be combined with other theories that involve interpersonal interaction with people in a different state of being that are influenced by their state.

Beck integrated the Carkhuff Seven Skills into his Spiral Dynamics practice. Some cases are described here.

In the Police

During an interview with Rica Viljoen in May 2017 in his office in Denton, Dallas, Don remembered:

We had a contract from the Ford Foundation to deal with conflicts between Dallas Police and various elements in the city, from both South Dallas “projects” as well as urban settings. We designed a unique approach that equipped officers in the field to go far beyond the cultural awareness programs of that day since they needed skills beyond simply walking away from a conflict or sending troublemakers to jail. I was working with Dr Robert Berg in the counselor education program at UNT. We used the Systemic Humans Relations Training from Robert Carkhuff; the Seven Dimensions.

We taught officers the Empathy, Warmth and Genuineness skill packages and even the most traditional thinking “Red Necks” were able to produce amazing results. We drove with the officers in deep-night shifts. Since we had “Black” citizens but “White” officers it did not matter. Race-based charges ended. We had a similar result with South African police and radical agitators in the townships in Middelburg.

In Sports

Don continued with his reflection:

In sports, I was working with Fred Akers and the UT football coaches (don't tell my rapid Boomer Sooner OU fans). I wrote about a player in a training exercise who exclaimed: “Hey coach, I'm going to start at linebacker. I am so excited. I can't wait to tell my dad and my girlfriend, I am so excited. My family and friends would be so proud of me. I'm starting at linebacker with the ‘Horns’ in the Cotton Bowl!”

I asked each of the eight coaches to react. They all responded: “That's nice, but you need to keep working hard to keep your position.” They all laughed eventually at their failure to demonstrate the basic Empathy, Warmth and Genuineness skills, but became judgmental, gave “fatherly” advice, and talked about themselves. In each case the player stopped talking and communication ceased.

This is an extremely powerful concept and skill to use in law enforcement, education and as conflict management.

The Seven Steps of Functional Design

The decision-making formulas that we use today are arguably inadequate for solving wicked complex systemic problems. Typically, we stop at dialogue and deliberation when trying to solve our conflicts (FS or GREEN codes of creating equality). Deliberation is not enough, we must design systems to make real the solutions on which we deliberate. In the following section the Seven Steps of Functional Design, as formulated by Beck and Johns (2017), are described.

Debate – Competitive, to Convince Others

People hold one view and then push strongly by finding flaws in other arguments. This adversarial argument polarizes the thesis and antithesis of the argument. The goal of the debate is to beat the opponent. This tactic is helpful in finding flaws in an argument, and in learning whether the weakness can be strengthened in an argument, or whether the logic is fatally flawed. During debate disagreement is discovered.

Dialogue – Talking Together Using Anecdotes and Personal Life Experiences

Dialogue is the process of generating collective learning, shared meaning and commitment for implementation. People talk with each other, and not necessarily against one another, and seek shared understanding. Bohm (1998) explained that it is aimed at understanding consciousness per se, as well as at exploring the problematic nature of day-to-day relationships and communications. The process of dialoging can be very time-consuming and should move through the Seven Steps in a well-planned facilitated manner.

Deliberation – Trying to Understand and Beginning to Create a Solution

Typically, dialogue leads to the identification of areas of agreement, and probes in depth for some discoveries. It also facilitates the holding of various viewpoints on a topic. During deliberation the group explores the various points raised to seek a deep, meaningful understanding. At times, people stop at deliberation, but in order to effect systemic change, solutions often have to be designed.

Diagnosis – Different Hypotheses Are Posed

After the first three steps we begin to have the history of a problem from multiple different points of view, which allows a group to create a hypothesis about the problem. Different attempts are made to understand the dynamics at play in the system. Analysis of the critical thought structures which generate the possibilities for progress is possible.

Design

In this step a plan is co-designed for addressing the hypotheses that take all of the varied viewpoints and problems into account. During this phase, the group searches for the dynamics that will continue the problem and make it worse. The impetus is to try it out. There could be bias towards action and field testing. Joint action planning can be facilitated.

Dismissing – Forms of Dismissing the Status Quo by Off-loading

The Sixth Step of Functional Design asks groups to dismiss the status quo. Senge, et al. (2004) described this stage as letting go in order to let be. Three methods of dismissing the status quo are:

Disengage – Keeping what is useful.

With this method, an organization gets rid of what they no longer need, and keeps only what is necessary.

Destroy – Getting rid of total systems that are in place.

Decommission – Preserving, to honor and celebrate the progress of systems. Here we celebrate the establishment of new systems.

Deployment

Deployment of the new system consists of implementing and laying out the proposed solutions, co-designed in Step 5. Here the new systems are embraced and constructed. During this step glitches that were not anticipated may be uncovered.

The Impact of Language

In an interview with Beck (2017) on the use of language, he reminds us of the following:

Take the insanity out of semantics. For example, whenever Trump would say that he is opposing Muslims, he should rather say “some Muslims.” He should have said SOME Muslims. Otherwise he is accused of stereotyping all Muslims, that was not his position. The same applies to the statement “Mexicans.” By saying “some Mexicans,” his stance is correctly transferred. He gets himself in serious trouble as he was not indexing. We must all watch our language else we can convey hurtful stereotypes that may be damaging and hurtful, permanently destroying relationships. Indexing means that we use SOME in front of categories of people in an effort not to use a stereotype for entire classes of people which is 1) not true and 2) leads to misunderstanding for which you have to pay a price later on.

For Trump, Beck (2017) reasons, it was almost fatal.

Dating means that we recognize that words have meaning in a certain date context. Sometimes we project what we thought years ago, and it is not applicable in the here and the now. It was applicable then. In order to build relationships and also enhance self-awareness, we need to find out if the opinion is recent, or dated. The whole matter of dating forces us to put ideas in time context and define them based on today. People do indeed change. Dating is what makes it essential that we look at the time frame in which a word has a meaning – because it is trapped in that time frame.

Abbreviated commas or quotes are our way to signal that this word has a particular meaning which I may or may not ascribe to it; but as it is used by others, I put quotes on it to separate it from other meanings of that term. All of us do this in order to separate ourselves from particular concepts of this meaning or terms. This is in fact a danger sign to say “watch out, I am using it as some people are using it this way; but not me necessarily.” This way I am denying that this word has any particular meaning.

Hyphenation is when our language lacks a single word to explain our reality. We often fuse two words together in order to convey the meaning of it today. The hyphen is a way to make a new word out of two things; neither one of these carries the full meaning of the new word. We create a hybrid word. The hyphen means partly this word and partly that word together because you cannot define what I am meaning with just one word. It is an attempt to construct a better meaning through the combination of words.

The next is IS-illness. This problem stems from the fantasy that I can tell you all about something. You cannot. This is a naïve statement. Ideas and words have richer and more complex meanings than you can convey. The idea here is to recognize that reality.

In the context of Spiral Dynamics, these aspects become very important as different codes use language differently. Laubscher (2013) explains that the brain is programmed in the lingo of the mother tongue. Sharon Underwood (1984) developed the BrainScan instrument for her PhD, which differentiates between digital and analogue thinking.

In this chapter, Spiral Dynamics PLUS, supplementary technologies were introduced that have a philosophical, theoretical and practical interface with Spiral Dynamics. Topics incorporated were Adizes, the use of Vital Signs Monitors, the assimilation contrast effect, value engineering, Carkhuff's Seven Skills, Seven Steps of Functional Design and the importance of integrating the nuances of the use of language. In the next chapter, some practical application of Spiral Dynamics is provided, and additional source material is made available to the reader.