Federal and State Energy Policies

The United States is far behind its competitors in national-level solar policy, which is expected given that it has never had a comprehensive energy policy. While the federal consumer tax credit of 30% for solar systems is one of the strongest drivers of the industry, the incentive structure from the US government is more of a patchwork quilt than a comprehensively and cohesively developed plan. Unlike its rivals, it has no national feed-in-tariff legislation and no renewable portfolio standard.

Many states are filling in the gaps, with consumer incentives, state targets, and other programs. The federal response is currently limited to tax credits and deductions, federal installations, and supporting R&D and innovation for early stage concept development.

Keywords

United States solar policy; feed-in-tariff; renewable portfolio standard; consumer incentives; solar tax credit; solar tax deduction

The United States is far behind its competitors in national-level solar policy, which is expected given that it has never had a comprehensive energy policy. While the federal consumer tax credit of 30% for solar systems is one of the strongest drivers of the industry, the incentive structure from the US government is more of a patchwork quilt than a comprehensively and cohesively developed plan. Unlike its rivals, it has no national feed-in-tariff (FIT) legislation and no renewable portfolio standard.

This chapter is a summary of policies at the state and federal level which are subject to consistent change. While the information represents the author’s best attempt to organize existing information, solar professionals should not rely on the information for decision-making, and should consult tax and legal professionals regarding the application of specific provisions.

Federal Policies

The United States does have a number of important policies and incentives, however, though many are set to expire in the near term and most function to reduce costs rather than to support markets for the energy (see the contrast with Germany in Chapter 5).

Tax Credits

Personal Tax Credit

Perhaps the most important federal solar policy in the United States—and certainly the most important to the residential market—is the personal tax credit for renewable energy systems. This credit, initially enacted in 2005, allows taxpayers to take a credit of up to 30% of the installed cost of a solar-electric or hot water system. The bill, which initially included a cap of $2000 and was not applicable to Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) payers, was amended and extended as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA, or “the stimulus bill”).

The ARRA revision removed the $2000 cap, allowed AMT payers to claim the credit, and extended its provisions through 2016. This last piece has been important to provide stability, however, if it is not reenacted, expect 2016 to be a bumper year for residential solar (to maximize the credit) followed by a substantial downturn in 2017. Despite price declines, the 30% tax credit is an integral piece to the affordability of solar systems. Its extension is crucial to the continued success of the residential market.

Investment Tax Credit

Similar to the personal tax credit, the corporate Business Energy Investment Tax Credit (ITC) allows for a 30% credit with no limit for most solar technologies. Approved applications include solar-electric systems and water heating, though pool heating and passive solar systems are excluded (similar to the personal credit). It is similarly set to expire on December 31, 2016, after being extended and amended several times since its enactment; however, the ITC will not disappear but the credit for solar-electric systems will drop from 30% to 10%.1

Advanced Energy Manufacturing ITC

Rounding out the tax credits is the Advanced Energy Manufacturing ITC. This incentive allows a tax credit of up to 30% of qualified investments in creating, retooling, or expanding manufacturing facilities that produce clean energy products. The $2.3 billion program has a cap of $30,000, with $150 million allotted for 2013.

The credit applies to tangible property only (excluding buildings and other structures) and is typically used for investments in equipment. To receive funds, manufacturers apply for the credit. The US Department of Energy makes recommendations to the US Treasury Department, which issues the certifications. Recipients have 1 year to meet all requirements and must have the equipment in service within 3 years from issuance. Importantly, business that claim this credit may not also take the ITC.2

Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System

One of the key federal incentives—particularly for larger scale systems and third-party financed leases—is the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). This provision allows corporations to accelerate the depreciation of property (in this case, solar systems) over a 5-year period. This depreciation can be a significant difference maker in third-party leases because companies receive significant depreciation of the property over the short term and pass the savings on to consumers.

While this system has been in place since 1986, recent years have had a series of bonus appreciation amendments. These amendments, beginning in 2008 and running through 2013 (so far), allow companies to deduct 50% of the property’s depreciation in the first year. This provision significantly reduces the up-front cost to consumers and allows for more rapid payback of solar systems.3

North Carolina State University’s Database of State Incentives for Renewable Energy (DSIRE) program notes this important caution: “The bonus depreciation rules do not override the depreciation limit applicable to projects qualifying for the federal business energy tax credit. Before calculating depreciation for such a project, including any bonus depreciation, the adjusted basis of the project must be reduced by one-half of the amount of the energy credit for which the project qualifies.”4

Grants

While the most prolific and widely applicable US federal solar incentives are tax credits and deductions, there are several targeted grant programs that offer direct cash payments to solar energy producers.

Rural Energy for America Program Grants

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) administers a direct grant program called the Rural Energy for America Program (REAP). The grants, ranging from $2500 to $500,000, can cover up to 25% of total project costs, and are designed to help agricultural producers and rural small businesses to reduce the cost of their energy by defraying system costs. Of specific importance to this grant, land grant and other universities may be eligible for funding (which typically cannot participate in tax credit schemes due to their nonprofit status), though K-12 schools are not eligible.5

USDA also has offered a High Energy Cost Grant Program since 2000. According to DSIRE, “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) offers an ongoing grant program for the improvement of energy generation, transmission, and distribution facilities in rural communities. This program began in 2000. Eligibility is limited to projects in communities that have average home energy costs at least 275% above the national average. Individuals, non-profits, commercial entities, state and local governments (including any agency or instrumentality thereof), and tribal governments are eligible for this grant. Individuals must work on a project that will benefit the community in order to qualify. Under the most recent solicitation for projects, a total of $7 million was available for qualifying projects.”6 While the most recent grant application closed on 2012, with a grant range of $20,000 to $3 million, USDA is likely to continue the program in the future. A loan guarantee fund is also part of the program.

Tribal Energy Program Grant

The United States Department of Energy offers several different grants to subsidize the cost of solar heating and cooling and solar-electric production on federal tribal lands. These measures vary frequently over time and solicitations can be tracked at: http://apps1.eere.energy.gov/tribalenergy/financial_opportunities.cfm.

Loans and Loan Guarantees

Another popular federal solar incentive program involved direct loans and loan guarantees. They are also controversial, after Solyndra filed for bankruptcy and failed to repay its loan.

Department of Energy Loan Guarantee Program

The Department of Energy developed a loan guarantee program in 2005, called the 1703 program. As part of ARRA, this program was expanded by adding a section 1705. The 1705 program expired in 2011, but the original authority to provide up to $10 billion in energy-related projects under 1703 remains.

The program specifically focuses on manufacturing facilities, renewable energy projects, and integrated projects. Repayment terms are quite favorable, with a maximum period of 30 years or 90% of the assets’ expected useful life.7

Clean Renewable Energy Bonds

Clean Renewable Energy Bonds (CREBs) were a popular funding mechanism that were similar to other forms of bond financing, though the credits are subject to income tax unlike many public bonds. The federal CREB program is no longer accepting applications (administered by the Department of the Treasury) but many states do.

Qualified Energy Conservation Bonds

According to the Center for Sustainable Energy, “Qualified Energy Conservation Bonds (QECBs) can be used by local and state government agencies on a wide range of activities; nationwide the QECB program is funded at $2.4B; each state has received an allocation based on population, and each state must develop its own mechanism for how allocations are awarded to individual projects. The ARRA authorized local communities to use some or all of their QECB allotment for funding municipal solar and energy efficiency projects, including capital expenditures that reduce energy consumption on publicly-owned buildings by at least 20%, and implementing green community programs. Such ‘green community programs’ could include many opportunities for cities, which could issue QECBs to fund loan, rebate and/or grant programs….”8

QCEBs function by providing a tax credit to the bondholder in lieu of the issuer paying interest to the bondholder. This is therefore equivalent of interest-free financing. Of current and specific use for solar activities, many municipalities and states are issuing QCEBs for community-based solar.

QCEBs are different from CREBs because they are not subject to the Department of Treasury approval process. Rather, they are based on each state’s population as of July 1, 2001, and then states allocate to local governments based on their size as well.9

State Policies

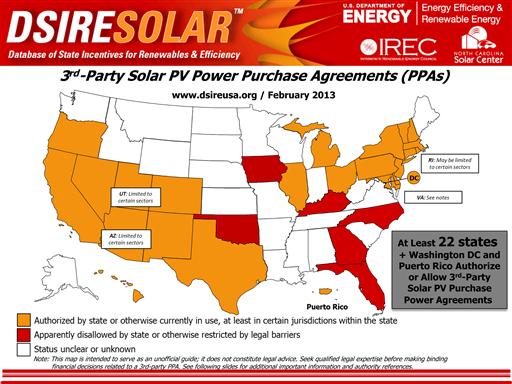

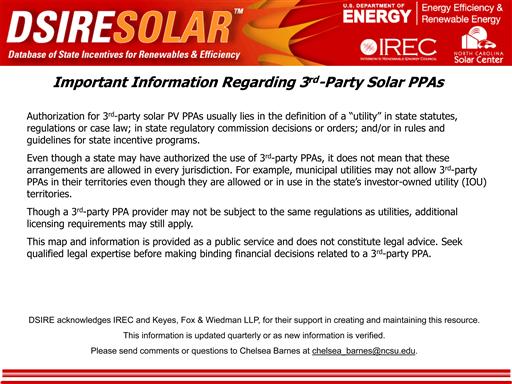

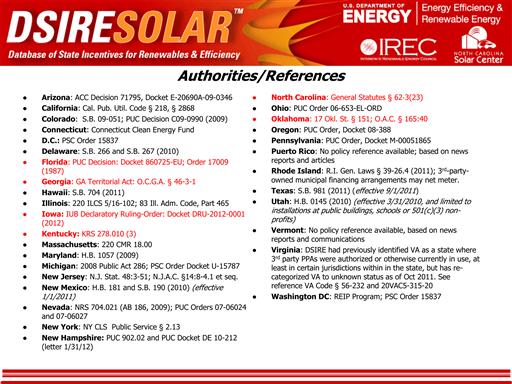

The lack of a national renewable energy policy has led many states to act on their own. According to The Solar Foundation’s Solar Jobs Census, state legislation, including renewable portfolio standards and third-party ownership allowance, was the second most important factor for their growth.

This section identifies and explains various state-level incentives, while providing examples of activity from around the country. The DSIRE10 is the most comprehensive source of up-to-date state-level incentives, available on the Internet at http://dsireusa.org.

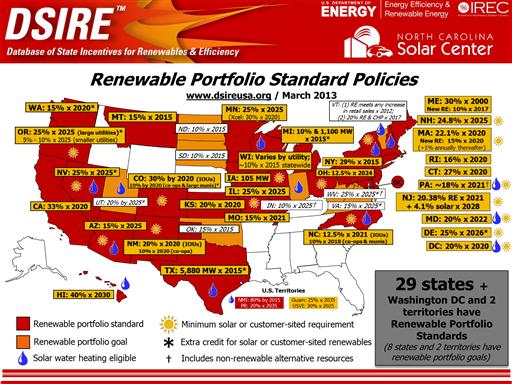

Renewable Portfolio Standards

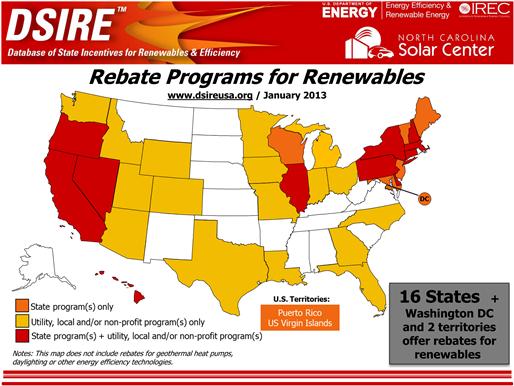

As cited previously in this text, a renewable portfolio standard is an important forcing tool used by states to spur the deployment of clean energy, and most frequently, solar power. The United States is far behind its competitors with its lack of a national standard, but many states have filled the gap. The below map illustrates the states with an adoptedrenewable portfolio standard, and is followed by another map, which shows those with a specific solar requirement.

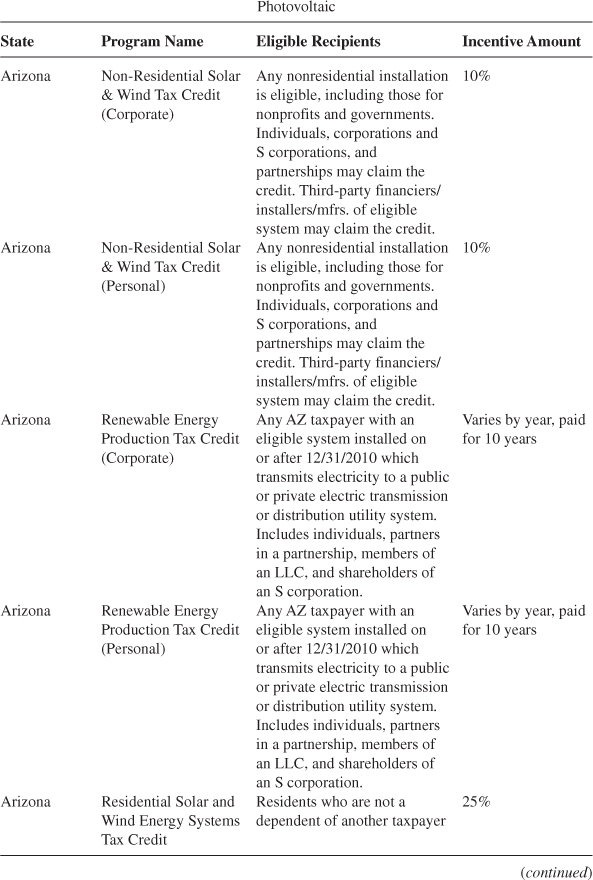

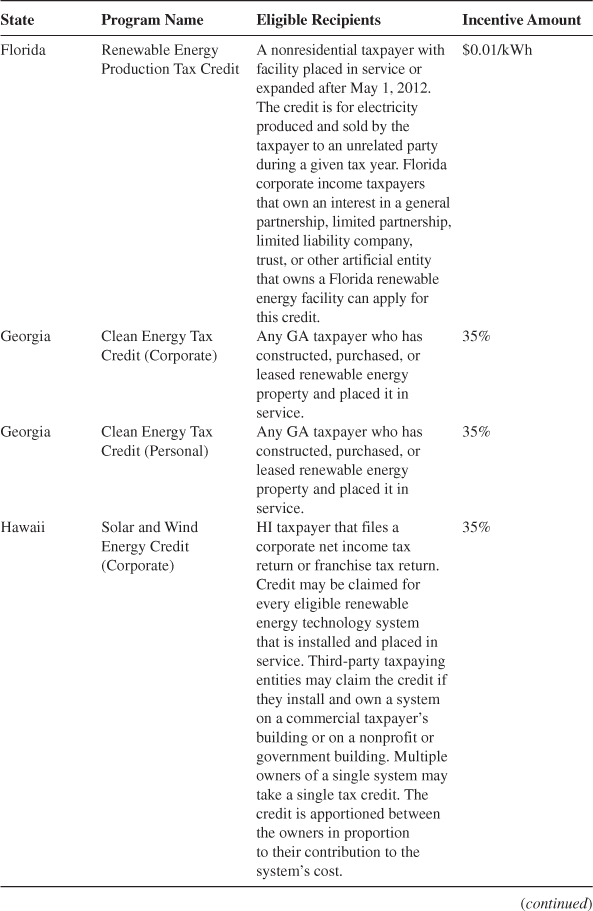

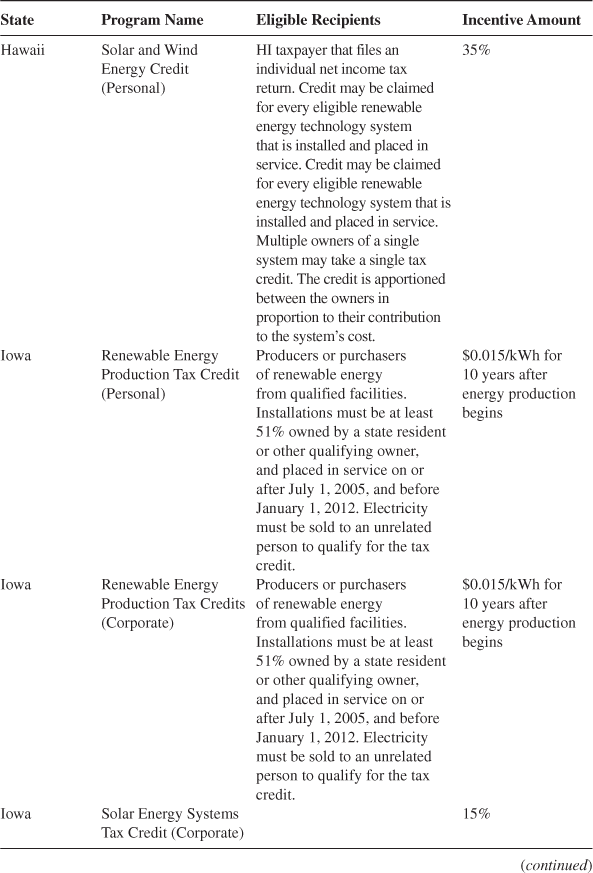

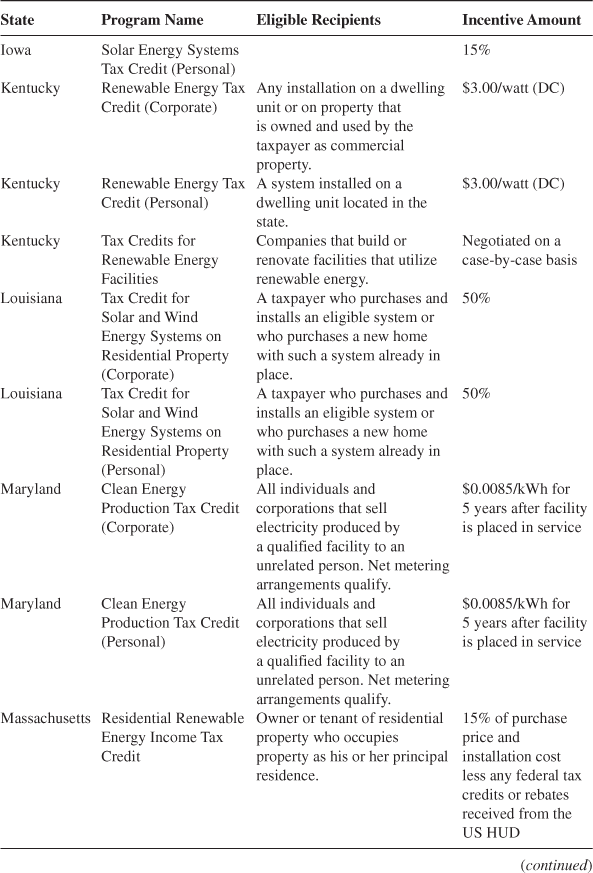

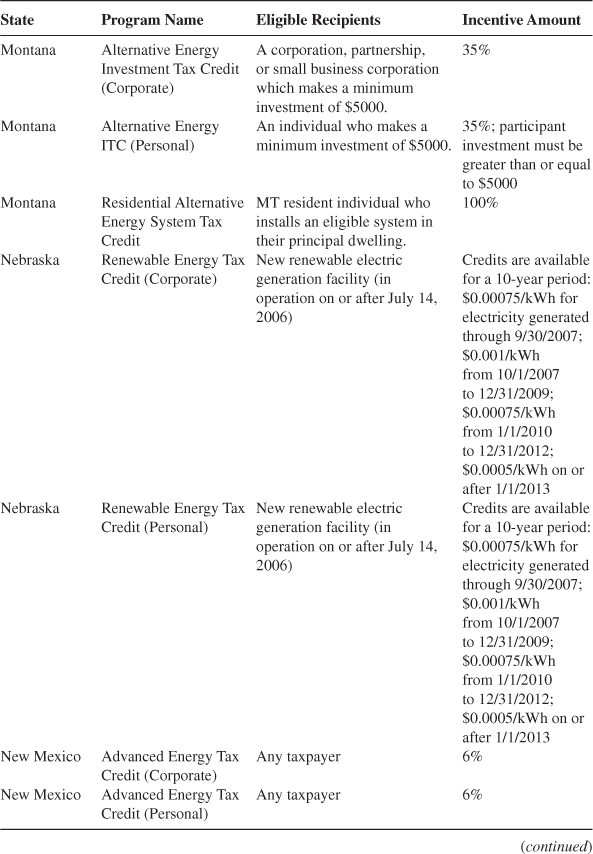

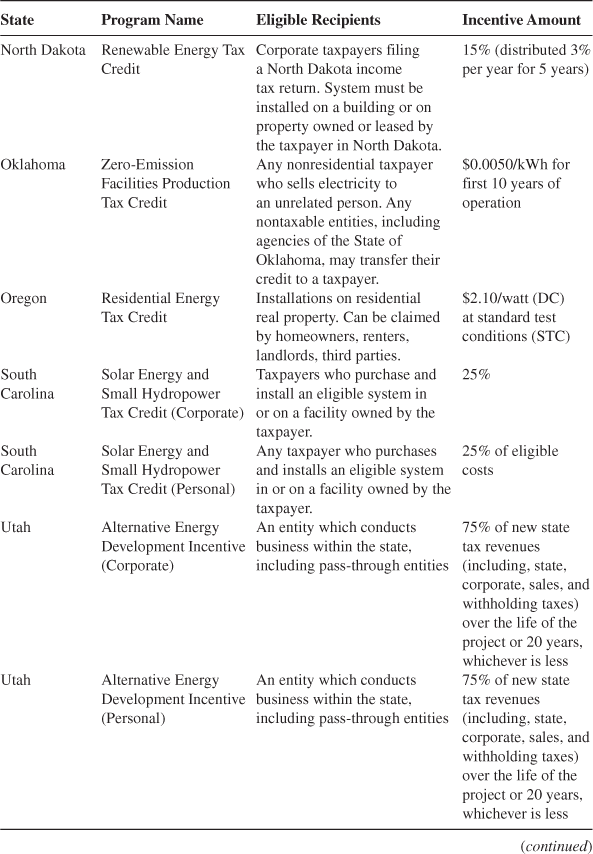

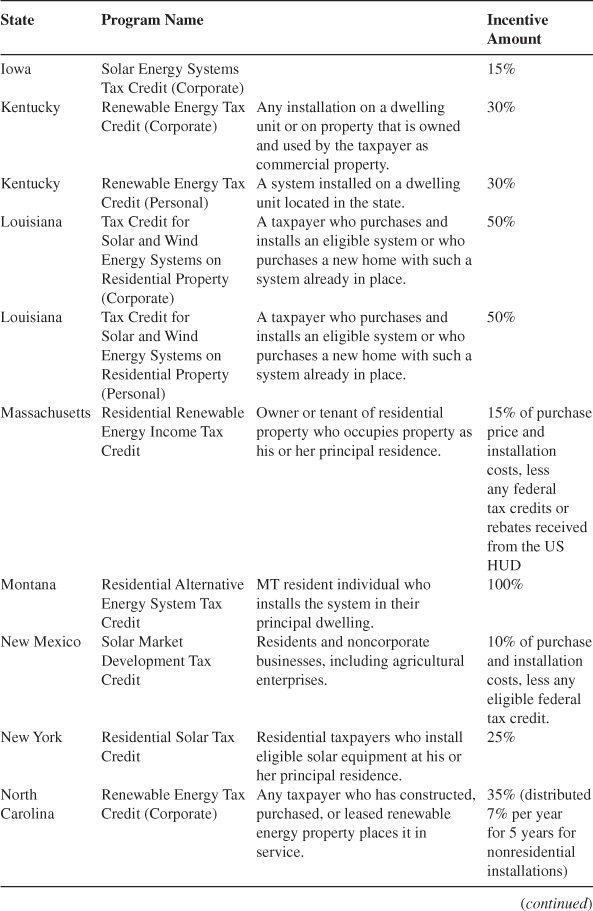

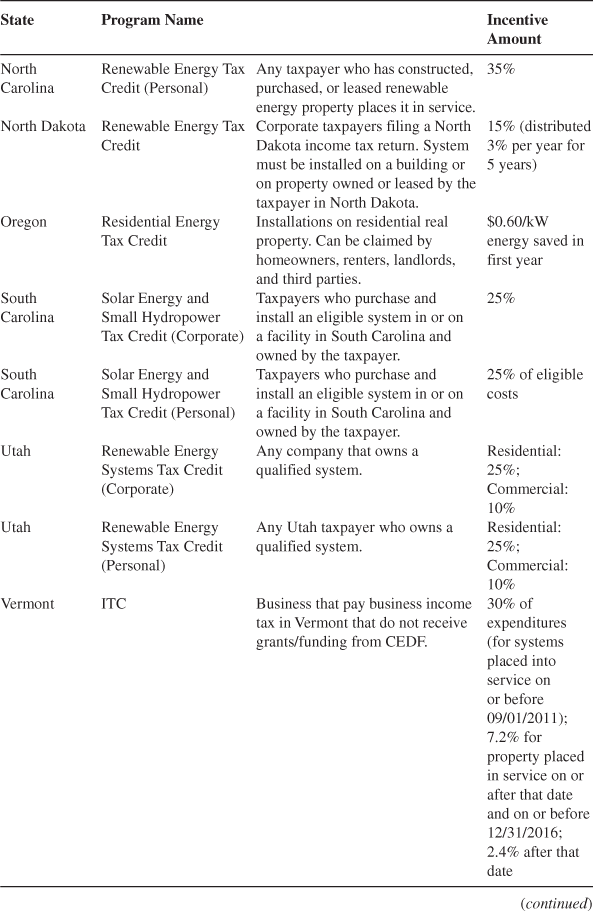

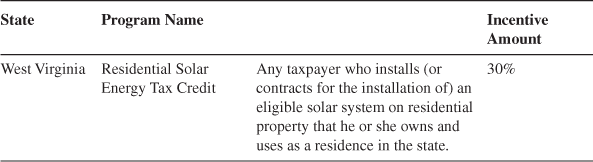

Tax Credits

Tax credits are the most popular US solar incentive. A tax credit simply refers to a reduction in tax liability, typically at the state or local level (though some municipalities and counties that tax income also offer credits). The primary benefit of a tax credit for consumers are reduced overall pricing (and though delayed until tax filing) and lower up-front costs. While the state and municipal tax credits are generally not enough to have dramatic impacts on the cost of the systems, it is often enough to push potential buyers who are on the fence.

States often prefer tax credits because they reduce receipts rather than increase expenditures. While this has the same end result on the treasury, they differ in at least three important ways. First, tax credits do not require the same administration. System costs can often be simply included on a tax return. Second, funding does not need to be allocated. It is a hit on revenue, not a new expense. Third, it is more politically palatable. It is much easier for a politician to vote in a tax cut as opposed to approving new spending. Especially in this time of state and federal budget austerity, many states do not have the ability to directly fund cash or other incentives, so a tax credit is a more viable option to promote the industry.11

There is another, equally important aspect to tax credits, particular to larger projects and focused on investments. These commercial tax credits allow developers and third-party financiers to take advantage of reducing tax liability to defray project costs. According to North Carolina State University’s analysis, “tax credits generally range from 10% to 50% of project costs [and the] maximum credit generally ranges from $500 to $35,000 for residential systems and from $25,000 to $60 million for commercial systems.”12

While tax credits often cover solar-electric and solar thermal systems, they do have some important drawbacks, primarily in that they only function for entities with tax liabilities. As a result, many nonprofits, educational institutions, churches, and government agencies cannot benefit from them. Third-party financing and power purchase agreements (so-called “solar leases”) have mitigated some of these concerns because the developer/installer can take the credit, but the reliance on tax credits has slowed the installation of solar systems in some segments of the market.

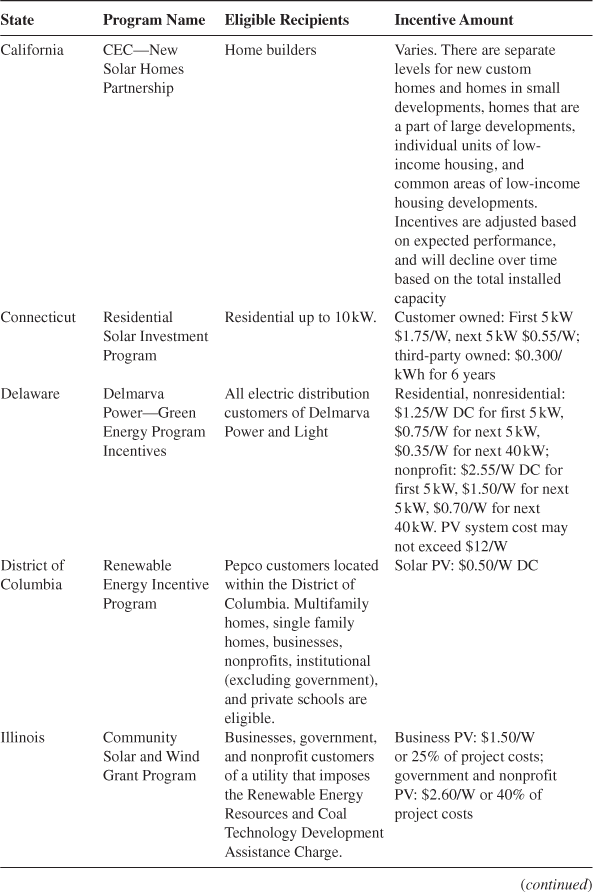

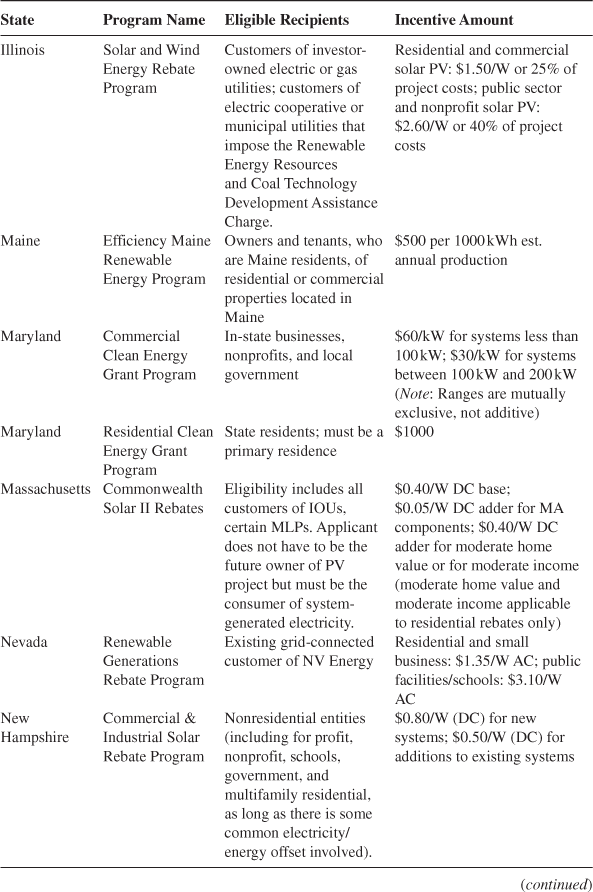

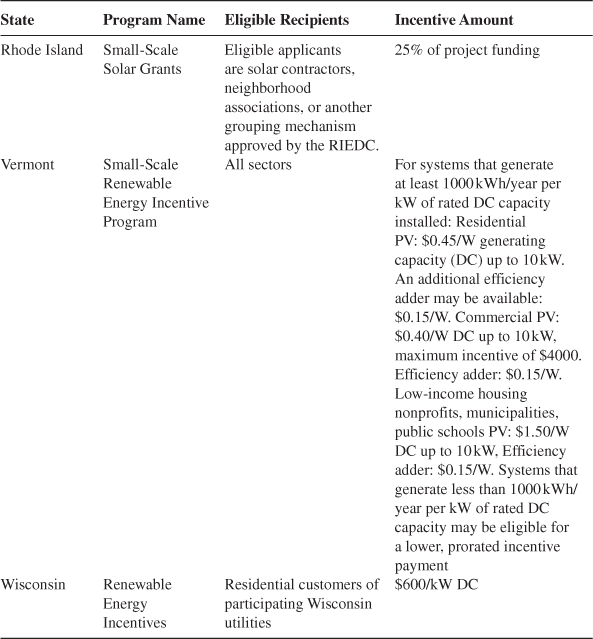

As of June 2013, about 20 states are represented in DSIRE’s database for tax incentives, included below:

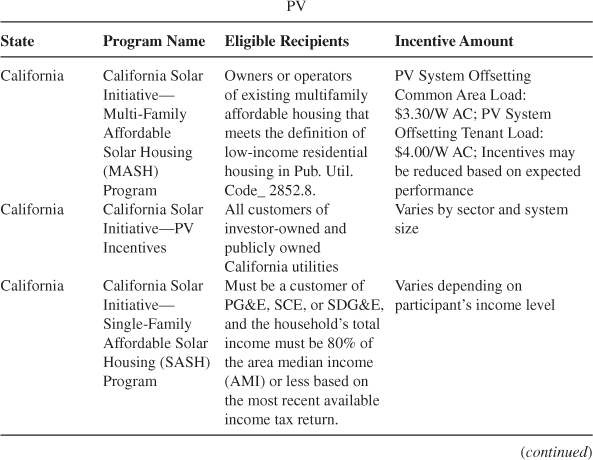

Direct Cash Financing

This broad category of incentives includes rebates, grants, and performance-based incentives. The most simple form of direct cash financing is a rebate, which is simply a payment made to the purchaser after installation. This is similar to typical consumer rebates; however, because of the complexity and safety requirements for solar systems, several inspections are often required prior to installation. Rebates range in value. Massachusetts is an example of a very strong solar rebate, offering up to $2500 to purchasers of residential solar systems.

Similar to rebates, a buydown is a reduction in the bottom-line cost of a system to a buyer, where the funder makes a direct payment to the seller or installer as opposed to the consumer. This can be beneficial to consumers as it tends to reduce the potential for lag between going out of pocket and receiving the rebate.

Grants are generally not as common for residential installations and usually involve competitive applications. Solar program administrators and consumer often use rebates, buydowns, and grants interchangeably, as all three are typically based on system size, capital costs, or system performance.13

While some incentives, such as the Massachusetts solar rebate program, use expected system output as their basis for payment, but performance-based incentives, however, are paid by “actual energy output of a solar energy system (to encourage optimal system design and installation) and are disbursed over several years. FITs and renewable energy credit (REC) purchase programs are examples of performance-based incentives. Direct cash incentives may be offered by states, local governments and/or utilities.”14

Direct cash incentives are Keynesian in nature, in that they serve to stimulate the market to encourage efficiency and investment throughout the value chain, ultimately dropping the price of solar products and services. Specifically, direct cash incentives offer the following benefits:

1. Reduced up-front costs (rebates, buydowns, and some grants, etc.);

2. Continued and supported revenue stream (performance-based incentives);

3. Reduced return on investment and lower overall costs to consumers;

4. Offered immediately (or nearly so) rather than at tax year-end and are provided regardless of tax liability.

In essence, these programs distribute some of the costs not over time as Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) does, but across the populace. The cash to support these programs comes from taxpayers or rate payers, on the premise that cost distribution should accompany benefit distribution, as the climate, security, and peak production of solar benefits all electric customers and not just the end-purchaser.

As of mid-2013, over 20 states and 200 utilities offer some form of direct cash financing. Generally, these programs defray 10–30% of the cost of the system and are seen as being one of the most important components to competitive pricing and a burgeoning solar installation market in the United States.15 According to the 2012 Solar Jobs Census, a lack of consumer incentives was the second most reported obstacle to growth, suggesting that even more can be done with direct cash incentives.16

Despite the popularity of these incentives, they have many detractors. In addition to legislators who do not generally believe in Keynesian Economic Theory or externalized cost distribution, direct cash incentives require direct funding mechanisms. These mechanisms are generally more difficult to develop, can be more costly to administer, and are often subject to raid when budgets become tight.17

International comparisons show the promise of a mechanism that is gaining popularity among US states called a FIT. This mechanism works by requiring utilities to purchase excess power from solar systems at a fixed rate for a specific number of years. Many programs also require the utilities to pay the renewable energy credits, if applicable. The FIT system is the basis of the European model, addressed later in this chapter, because it provides a stable, ongoing revenue stream and market for the renewable energy.

Recently, the North Carolina Solar Center, at NC State University, conducted an analysis of direct cash incentives that is a valuable summary of the benefits. An excerpt of that analysis follows (which has been republished with their permission):

Most state programs have since adopted more complex incentive structures to incorporate and address four primary issues that have emerged as solar markets have evolved:

• The different tax treatment of residential, commercial and non-profit sectors. About one-third of state PV programs and several state solar water heating programs provide larger incentives to the government/non-profit sector because these entities cannot easily take advantage of state and federal tax credits.

• The desire to reward system performance rather than system capacity. Performance-based incentives, which provide project owners with long-term payments based on electricity production on a dollar-per-kilowatt-hour basis, have gained increasing attention. So, too, have hybrid approaches, which sometimes involve upfront rebates based on a system’s expected performance. Such incentives are based on system capacity but may be adjusted after taking into consideration certain other factors, including system rating, location, tilt, and orientation and shading. Payments based on performance or expected performance rather than capital investment have gained prominence as a means of incentivizing proper system design and installation.

• Other mechanisms to protect consumers and guarantee adequate performance. Ensuring that solar energy systems will perform as expected solidifies consumer confidence and helps guarantee that a state is making prudent investments. Beyond tying incentive payments to actual system performance, states have developed quality-assurance mechanisms that include one or more of the following provisions: equipment and installation standards; warranty requirements; installer requirements, assessments, and voluntary training; design standards and administrative design review; post-installation site inspections and acceptance testing; performance monitoring and assessment; and maintenance requirements and services. The best approach will ultimately depend on the performance issues of greatest concern and will differ depending on each program’s objectives and constraints [3].

• Interest in rewarding high-value or emerging applications. Providing bonus incentives for desirable applications is becoming increasingly common among state programs. Current and past examples include higher incentives for affordable housing; for the use of in-state manufactured components; for the use of building-integrated PV; for the use of certified installers, and installations in certified green buildings; and for solar on Energy Star homes, new construction and public buildings.18

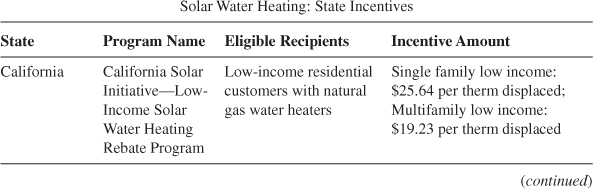

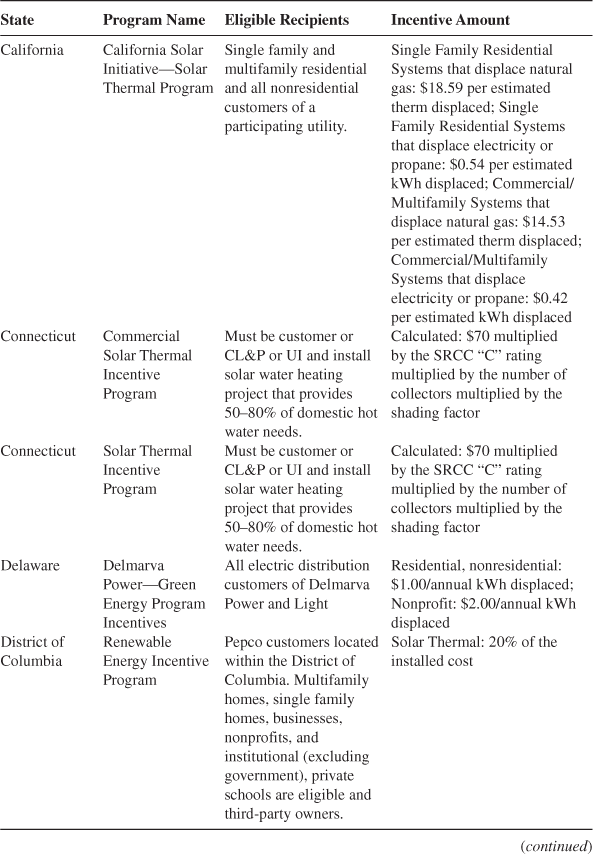

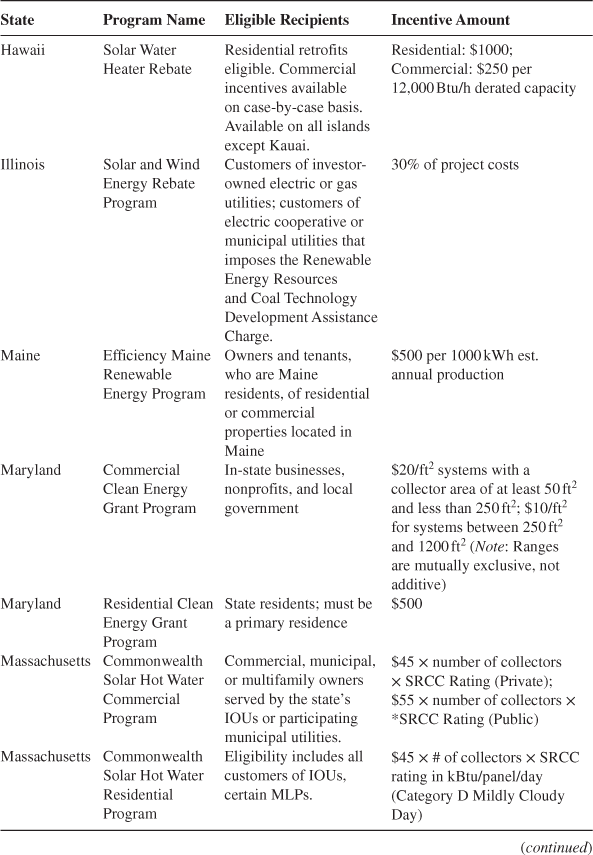

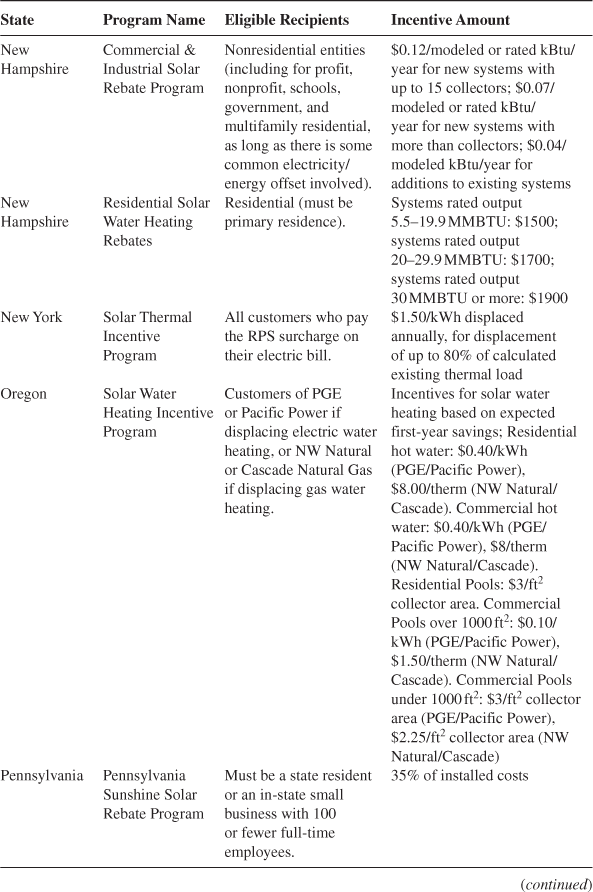

Below are the DSIRE tables of state solar cash incentives for PV and water heating as of mid-2013:

PACE

One of the most promising programs, PACE financing, has also been the most challenging to enact. PACE operates by providing financing that spreads out the cost of renewable energy and energy efficiency home and business upgrades over time, using the property as the collateral. Importantly, PACE programs follow the property rather than the owner. As a result, building owners need not consider the payback horizon in terms of when they might sell the property, but rather focus on the impact at sale (which is generally expected to be quite positive).

PACE operates differently from other financing related to property improvements. First, there is no personal liability outside of the property, similar to municipal property tax. Second, there are typically no up-front closing costs. PACE typically operates at the municipal level, whereby the local government provides the financing and adds the capital expense to existing property tax or a special assessment (sometimes through a municipally owned utility).

PACE financing offers many benefits. These include financing that is fixed in cost and spread out over a long period of time; interest rates based on the value and tax capacity of a home rather than the borrower’s credit history; attachment of the loan to the property rather than the individual, making it transferable at sale; and sometimes favorable tax status, similar to deductions for local property taxes.19

PACE programs must be approved by local government, and in some instances, by states (if those states do not have home rule). While many states and municipalities have acted over the last several years, the initial programs (favorably for consumers) placed the special assessments ahead of mortgages in priority. This put the assessments on equal footing with property taxes and behind mortgages, creating a stir in the banking industry.

According to the DSIRE20:

Local PACE programs are currently operating in at least nine states (California, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New York and Wisconsin) and the District of Columbia. In 2012, California launched a massive PACE program that, at its inception, allowed non-residential property owners in 126 cities and 14 counties to finance renewable energy, energy efficiency and water-efficiency projects. In other states, many residential PACE programs, especially those in states that have positioned PACE financing as the senior lien on a property, are currently on hold due to challenges created by the Federal Housing Finance Authority’s (FHFA) stance on these programs. The FHFA’s guidance directly impacts residential PACE programs (but not non-residential PACE programs) and effectively makes most residential PACE programs that assign the senior lien to PACE financing impossible to implement. However, some states, such as Florida and Hawaii, already had a structure in place to allow local governments to finance solar-energy systems through PACE programs. In response to the FHFA restrictions, a few states have enacted legislation that explicitly removes the senior lien provision in PACE programs, granting PACE financing a subordinate lien instead. The FHFA must issue a final rule by September 16, 2013.

PACE funding is perhaps the most important consumer-related driver to impact the future of the solar industry. Its primary benefits include:

1. Up-front financing. This is a major obstacle for a majority of would-be solar customers;

2. Transferability. People in the United States are mobile and have concerns about lingering financial liabilities in case of a move;

3. Low risk, low rates. Because the program is based on property values and tax capacity and not credit rating, the cost of financing is relatively low.

These benefits are increasingly important in the United States because the demographic most likely to install solar, and to have the capital and income to make the investments, tend to be closer to retirement and moving than average. PACE is a way for baby boomers, many of whom have strongly favorable views of solar energy, to partake in the market without leveraging their retirement savings.

Below is a summary of state-level PACE programs in place as of mid-2013:

• Local Option—Property Assessed Clean Energy Financing

• Local Option—Municipal Energy Districts

• California Enterprise Development Authority—Statewide PACE Program

• City of Palm Desert—Energy Independence Program

• City of San Francisco—GreenFinanceSF

• Los Angeles County—Commercial PACE

• Sonoma County—Energy Independence Program

• Western Riverside Council of Governments—Home Energy Renovation Opportunity (HERO) Financing Program

• Western Riverside Council of Governments—Large Commercial PACE

• Local Option—Improvement Districts for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Improvements

• Local Option—Commercial PACE Financing

• Local Option—Residential Sustainable Energy Program

• Property Assessed Clean Energy Financing

• Local Option—Special Districts

• Miami-Dade County—Voluntary Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Program

• Local Option—Special Improvement Districts

• Local Option—Special Improvement Districts

• Local Option—Contractual Assessments for Renewable Energy and/or Energy Efficiency

• Local Option—Sustainable Energy Financing Districts

• Local Option—Property Assessed Clean Energy

• Local Option—Clean Energy Loan Program

• Local Option—Energy Revolving Loan Fund

• City of Ann Arbor—PACE Financing

• Local Option—Property Assessed Clean Energy

• Local Option—Energy Improvement Financing Programs

• Jefferson City—Property Assessed Clean Energy

• Local Option—Clean Energy Development Boards

• Local Option—Special Improvement Districts

• Local Option—Energy Efficiency & Clean Energy Districts

• Local Option—Property Assessed Clean Energy Financing

• Local Option—Renewable Energy Financing District/Solar Energy Improvement Special Assessments

• Local Option—Municipal Sustainable Energy Programs

• Town of Babylon—Long Island Green Homes Program

• Local Option—Clean Energy Financing

• Local Option—Special Energy Improvement Districts

• Local Option—County Energy District Authority

• Local Option—Local Improvement Districts

• Local Option—Contractual Assessments for Energy Efficient Improvements

• Local Option—Commercial PACE Financing

• Local Option—Property Assessed Clean Energy

• Local Option—Clean Energy Financing

• Local Option—Energy-Efficiency Improvement Loans

• River Falls Municipal Utilities—Renewable Energy Finance Program

Property Tax Incentives

Property tax incentives are important for the long-term health of the solar industry, but are not generally stimulating activity. Such incentives essentially exclude the value of the system from the property assessment, so that homeowners do not have to pay additional property tax for the improvement. This puts solar systems in a different category from other improvements (such as swimming pools, sheds, and so on) but it is more of a removal of a potential negative rather than an affirmative addition.

This is not to minimize the importance of property tax incentives. With all of the potential barriers to homeowners (by now, it should be apparent that a much greater proportion of US incentive programs are focused on smaller-scale systems than in other parts of the world), increased property taxes would be another challenge. As a result, more than 30 states have enabling legislation regarding property tax incentives.21

As of June 2013, this is the DSIRE listing of property tax incentives by state:

• Local Option—Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy Systems

• Energy Equipment Property Tax Exemption

• Property Tax Assessment for Renewable Energy Equipment

• Property Tax Exclusion for Solar Energy Systems

• Local Option—Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy Systems

• Property Tax Exemption for Residential Renewable Energy Equipment

• Renewable Energy Property Tax Assessment

• Local Option—Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy Systems

• Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy Systems

• Solar Energy System and Cogeneration System Personal Property Tax Credit

• City and County of Honolulu—Real Property Tax Exemption for Alternative Energy Improvements

• Special Assessment for Solar Energy Systems

• Renewable Energy Property Tax Exemption

• Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy Systems

• Renewable Energy Property Tax Exemption

• Solar Energy System Exemption

• Anne Arundel County—High Performance Dwelling Property Tax Credit

• Anne Arundel County—Solar and Geothermal Equipment Property Tax Credits

• Baltimore County—Property Tax Credit for High Performance Buildings and Homes

• Baltimore County—Property Tax Credit for Solar and Geothermal Devices

• Carroll County—Green Building Property Tax Credit

• Harford County—Property Tax Credit for Solar and Geothermal Devices

• Howard County—High Performance and Green Building Property Tax Credit

• Local Option—Property Tax Credit for High Performance Buildings

• Local Option—Property Tax Credit for Renewables and Energy Conservation Devices

• Montgomery County—High Performance Building Property Tax Credit

• Prince George’s County—Solar and Geothermal Residential Property Tax Credit

• Property Tax Exemption for Solar and Wind Energy Systems

• Special Property Assessment for Renewable Heating & Cooling Systems

• Renewable Energy Property Tax Exemption

• Alternative Energy Personal Property Tax Exemption

• Wind and Solar-Electric (PV) Systems Exemption

• Renewable Energy Generation Zone Property Tax Abatement

• Corporate Property Tax Reduction for New/Expanded Generating Facilities

• Generation Facility Corporate Tax Exemption

• Renewable Energy Systems Exemption

• Large-Scale Renewable Energy Property Tax Abatement (Nevada State Office of Energy)

• Property Tax Abatement for Green Buildings

• Renewable Energy Systems Property Tax Exemption

• Local Option—Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy

• Assessment of Farmland Hosting Renewable Energy Systems

• Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy Systems

• Property Tax Exemption for Residential Solar Systems

• Energy Conservation Improvements Property Tax Exemption

• Local Option—Real Property Tax Exemption for Green Buildings

• Local Option—Solar, Wind & Biomass Energy Systems Exemption

• New York City—Property Tax Abatement for Photovoltaic (PV) Equipment Expenditures

• Active Solar Heating and Cooling Systems Exemption

• Property Tax Abatement for Solar Electric Systems

• Renewable Energy Property Tax Exemption

• City of Cincinnati—Property Tax Abatement for Green Buildings

• City of Cleveland—Residential Property Tax Abatement for Green Buildings

• Qualified Energy Property Tax Exemption for Projects 250 kW or Less

• Qualified Energy Property Tax Exemption for Projects over 250 kW (Payment in Lieu)

• Local Option—Rural Renewable Energy Development Zones

• Renewable Energy Systems Exemption

• Puerto Rico—Property Tax Exemption for Solar and Renewable Energy Equipment

• Local Option—Property Tax Exemption for Renewable Energy Systems

• Residential Solar Property Tax Exemption

• Renewable Energy System Exemption

• Green Energy Property Tax Assessment

• Renewable Energy Systems Property Tax Exemption

• Local Option—Property Tax Exemption

• Uniform Capacity Tax and Exemption for Solar

Economic Development Incentives

Economic developers use various strategies to entice businesses to their local communities. These programs, which are very popular in more managed economies such as in China, typically offer tax incentives, loans, or other enticements to build production facilities or locate R&D centers. They are the hallmark of traditional economic development policy and are typically measured by their ability to create local jobs.

Such programs do have a downside, as seen in the highly publicized Solyndra bankruptcy. Often, economic development incentives create a race to the bottom, with intense competition among regions. Also, the impacts can be short term. Perhaps, the most highly publicized case of an economic incentive backfire was in the City of New London, which took property from residents by eminent domain (an act it had to defend all the way to the US Supreme Court) and offered property tax abatements to pharmaceutical giant Pfizer. Eight short years later, Pfizer left, leaving an enormous empty campus, 1400 lost jobs, and virtually nothing for the city coffers.

However, economic development policies that are implemented correctly and thoughtfully can have an impact, though policy makers must be sure that they are not in a race to the bottom, and companies must ensure that they are deal sweeteners and not necessary for firm survival. Often, these programs will require a minimum level of leveraged investment, commitment of funders, or job creation. One useful example of a thoughtful economic development policy is to guarantee a certain amount of purchased product (for a manufacturing facility) or agreement to buy a certain amount of power (from a project developer), which works particularly well when the municipality runs the electric utility.22

Many of the same players offer economic development strategies among US states. The DSIRE database shows about 20 programs in 2013:

• Renewable Energy Business Tax Incentives

• Wind Energy Manufacturing Tax Incentive

• Sales and Use Tax Exclusion for Advanced Transportation and Alternative Energy Manufacturing Program

• Operational Demonstration Program

• Sales and Use Taxes for Items Used in Renewable Energy Industries

• Qualifying Advanced Energy Manufacturing Investment Tax Credit

• Miami-Dade County—Targeted Jobs Incentive Fund

• Solar and Wind Manufacturing Incentive

• Incentives for Energy Independence

• Alternative Energy and Energy Conservation Patent Exemption (Corporate)

• Alternative Energy and Energy Conservation Patent Exemption (Personal)

• Energy Revolving Loan Fund—Clean Energy Advanced Manufacturing

• Nonrefundable Business Activity Tax Credit

• Refundable Payroll Tax Credit

• Renewable Energy Renaissance Zones

• Mississippi Clean Energy Initiative

• Alternative Energy Investment Tax Credit

• Property Tax Abatement for Production and Manufacturing Facilities

• Edison Innovation Clean Energy Manufacturing Fund—Grants and Loans

• Edison Innovation Green Growth Fund Loans

• Wind Manufacturing Tax Credit

• Alternative Energy Product Manufacturers Tax Credit

• Renewable Energy Equipment Manufacturer Tax Credit

• Advanced Energy Job Stimulus Program

• Tax Credit for Manufacturers of Small Wind Turbines

• Tax Credit for Renewable Energy Equipment Manufacturers

• Alternative and Clean Energy Program

• Solar Energy Incentives Program

• Wind and Geothermal Incentives Program

• Puerto Rico—Economic Development Incentives for Renewables

• Renewable Energy Manufacturing Tax Credit

• Sales and Use Tax Credit for Emerging Clean Energy Industry

• Solar and Wind Energy Business Franchise Tax Exemption

• Alternative Energy Manufacturing Tax Credit

• Clean Energy Manufacturing Incentive Grant Program

Permitting

A common complaint of all businesses is the process for and cost of obtaining state and local permits. These permits for building, inspection, and design review are costly and can take a long time to complete. As a result, many jurisdictions have offered expedited and low- or no-fee permitting for solar projects.

North Carolina State University conducted a survey of various permitting plans across the country. They found that the cost of the permits ranged from $0 to $1200. Costs often rise as the system size increases.23

In addition to these hard costs, permits can cause substantial delays to solar deployment, typically because inspectors and other government agents do not understand solar systems. Expedited permitting, which literally puts the application to the “top of the stack,” is a critical component to illustrating commitment to solar.24

Interestingly, however, when asked to report the major obstacles facing the growth of their businesses, solar employers across the value chain did not mention permitting (nor labor costs or other typical economic development favorites). General economic conditions, lack of incentives, and low customer awareness were the most common responses.25

Because so many of these programs are offered at the local level, it is difficult to collect information on how many such programs exist. DSIRE includes the following programs on its list as of July 2013:

• Maricopa Assn. of Governments—PV and Solar Domestic Water Heating Permitting Standards

• Maricopa County—Renewable Energy Systems Zoning Ordinance

• Solar Construction Permitting Standards

• Solar Construction Permitting Standards

• City of San Jose—Photovoltaic Permit Requirements

• San Diego County—Solar Regulations

• Santa Clara County—Zoning Ordinance

• City and County of Denver—Solar Panel Permitting

• Solar Construction Permitting Standards

• Local Option—Building Permit Fee Waivers for Renewable Energy Projects

• Broward County Online Solar Permitting

• Statewide Renewable Energy Setback Standards

• Permits and Variances for Solar Panels, Calculation of Impervious Cover

• Model As-of Right Zoning Ordinance or Bylaw: Allowing Use of Large-Scale Solar Energy Facilities

• Clark County—Solar and Wind Building Permit Guides

• Solar and Wind Permitting Laws

• City of Portland—Streamlined Building Permits for Residential Solar Systems

• Model Ordinance for Renewable Energy Projects

• Expedited Permitting Process for Solar Photovoltaic Systems

Loan Programs

While loans have no impact on the overall cost of projects, they do dramatically reduce the up-front cost of any size solar project. At the residential level, the impact of this can be dramatic, because up-front costs can be significant; however, the payback is in reduced electrical bills over time. Even in some of the most competitive states in the US, this payback time can be too much for many consumers.

At the commercial level, loans allow for more projects and distributing fixed costs into the future, to align with cash flow. As with any investment, this allows capital to be used for expansion rather than being sunk into one project at a time.

States and municipalities can play a critical role in these loan programs by fully or partially guaranteeing the principal. Loan programs tend to be more politically palpable, and, if risks are managed properly, can result in revolving funds to spur more investment or actually produce a profit.26

These benefits seem compelling but are often not enough to encourage significant activity. As noted in Chapter 3, a relatively small percentage of consumers are willing to purchase “green” even if it costs more, and loans do nothing to reduce total costs. Despite this, DSIRE lists about 30 states that offer loan programs that include solar energy, summarized below:

• AlabamaSAVES Revolving Loan Program

• Local Government Energy Loan Program

• South Alabama Electric Cooperative—Residential Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• TVA Partner Utilities—Energy Right Heat Pump Program

• Small Building Material Loan

• Sulphur Springs Valley EC—SunWatts Loan Program

• First Electric Cooperative—Home Improvement Loans

• Energy Efficiency Financing for Public Sector Projects

• SMUD—Residential Solar Loan Program

• Boulder County—Elevations Energy Loans Program

• City and County of Denver—Elevations Energy Loans Program

• Direct Lending Revolving Loan Program

• Fort Collins Utilities—Residential On-Bill Financing Program

• Combined Heat and Power Pilot Loan Program

• Energy Efficiency Fund (Electric and Gas)—Residential Energy Efficiency Financing

• Low-Interest Loans for Customer-Side Distributed Resources

• Clean Renewable Energy Bonds (CREBs)

• Qualified Energy Conservation Bonds (QECBs)

• U.S. Department of Energy—Loan Guarantee Program

• USDA—Biorefinery Assistance Program

• USDA—Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) Loan Guarantees

• City of Lauderhill—Revolving Loan Program

• City of Tallahassee Utilities—Efficiency Loans

• City of Tallahassee Utilities—Solar Loans

• Clay Electric Cooperative, Inc—Energy Conservation Loans

• Clay Electric Cooperative, Inc—Solar Thermal Loans

• Gainesville Regional Utilities—Low-Interest Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Orlando Utilities Commission—Residential Solar Loan Program

• St. Lucie County—Solar and Energy Loan Fund (SELF)

• Athens-Clarke County—Green Business Revolving Loan Fund

• Flint Energies—Residential Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Georgia Cities Foundation—Green Communities Revolving Loan Fund

• TVA Partner Utilities—Energy Right Heat Pump Program

• City and County of Honolulu—Solar Loan Program

• Farm and Aquaculture Alternative Energy Loan

• KIUC—Solar Water Heating Loan Program

• Maui County—Solar Roofs Initiative Loan Program

• Idaho Falls Power—Energy Efficient Heat Pump Loan Program

• Low-Interest Energy Loan Programs

• South Central Indiana REMC—Residential Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Alliant Energy Interstate Power and Light (Gas and Electric)—Low Interest Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Alternate Energy Revolving Loan Program

• IADG Energy Bank Revolving Loan Program

• MidAmerican Energy (Gas and Electric)—Residential EnergyAdvantage Loan Program

• Energy Efficiency Loans for State Government Agencies

• Energy Efficient Home Improvements Loan Program

• Greater Cincinnati Energy Alliance—Residential Loan Program

• Inter-County Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Mountain Association for Community Economic Development—Energy Efficient Enterprise Loan Program

• Mountain Association for Community Economic Development—Solar Water Heater Loan Program

• TVA Partner Utilities—Energy Right Heat Pump Program

• City of Shreveport – Shreveport Energy Efficiency Program (SEED)

• Home Energy Loan Program (HELP)

• Seacoast Energy Initiative—Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Be SMART Multi-Family Efficiency Loan Program

• Jane E. Lawton Conservation Loan Program

• City of Detroit—SmartBuildings Detroit Green Fund Loan

• Energy Revolving Loan Fund—Farm Energy

• Energy Revolving Loan Fund—Passive Solar

• Energy Revolving Loan Fund—Public Entities

• Michigan Saves—Business Energy Financing

• Michigan Saves—Home Energy Loan Program

• Agricultural Improvement Loan Program

• Methane Digester Loan Program

• Minnesota Valley Electric Cooperative -Residential Energy Resource Conservation Loan Program

• Otter Tail Power Company—DollarSmart Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Sustainable Agriculture Loan Program

• Value-Added Stock Loan Participation Program

• Energy Investment Loan Program

• Mississippi Power (Electric)—EarthCents Financing Program

• TVA Partner Utilities—Energy Right Heat Pump Program

• Columbia Water & Light—Commercial Super Saver Loans

• Columbia Water & Light—Residential Super Saver Loans

• Alternative Energy Revolving Loan Program

• Dollar and Energy Savings Loans

• Valley Electric Association—Solar Water Heating Program

• Enterprise Energy Fund Loans

• Municipal Energy Reduction Fund

• Home Performance with Energy Star Program

• Drinking Water State Revolving Loan Fund

• Home Performance with Energy Star Financing

• Local Option—Financing Program for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency

• Lumbee River EMC—Solar Water Heating Loan Program

• Piedmont EMC—Residential Solar Loan Program

• Town of Carrboro—Worthwhile Investments Save Energy (WISE) Homes and Buildings Program

• TVA Partner Utilities—Energy Right Heat Pump Program

• Northern Plains EC—Residential and Commercial Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Otter Tail Power Company—Dollar Smart Financing Program

• Butler Rural Electric Cooperative—Energy Efficiency Improvement Loan Program

• Energy Conservation for Ohioans (ECO-Link) Program

• Greater Cincinnati Energy Alliance—Residential Loan Program

• Hamilton County—Home Improvement Program

• Community Energy Education Management Program

• Energy Loan Fund for Schools

• Higher Education Energy Loan Program

• Oklahoma Municipal Power Authority—WISE Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Red River Valley REA—Heat Pump Loan Program

• Ashland Electric Utility—Bright Way to Heat Water Loan

• Ashland Electric Utility—Residential Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• EWEB—Energy Management Services Loan

• EWEB—Residential Energy Efficiency Loan Programs

• EWEB—Residential Solar Water Heating Loan Program

• Lane Electric Cooperative—Residential Energy Efficiency Loan Programs

• Salem Electric—Low-Interest Loan Program

• Small-Scale Energy Loan Program

• Adams Electric Cooperative—Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Alternative and Clean Energy Program

• Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• High Performance Buildings Incentive Program

• Metropolitan Edison Company SEF Loans (FirstEnergy Territory)

• Penelec SEF of the Community Foundation for the Alleghenies Loan Program (FirstEnergy Territory)

• Small Business Pollution Prevention Assistance Account Loan Program

• Solar Energy Incentives Program

• Sustainable Development Fund Financing Program (PECO Territory)

• Sustainable Energy Fund (SEF) Loan Program (PPL Territory)

• West Penn Power SEF Commercial Loan Program

• Wind and Geothermal Incentives Program

• Berkeley Electric Cooperative—HomeAdvantage Efficiency Loan Program

• Blue Ridge Electric Cooperative—Heat Pump Loan Program

• Pee Dee Electric Cooperative—Energy Efficient Home Improvement Loan Program

• Santee Cooper—Renewable Energy Resource Loans

• Energy Efficiency Revolving Loan Program

• Otter Tail Power Company—Dollar Smart Financing Program

• Southeastern Electric—Electric Equipment Loan Program

• Commercial Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Energy Efficient Schools Initiative—Loans

• TVA Partner Utilities—Energy Right Heat Pump Program

• Austin Energy—Residential Solar Loan Program

• City of Plano—Smart Energy Loan Program

• LoanSTAR Revolving Loan Program

• Energy Project and Equipment Financing

• TVA Partner Utilities—Energy Right Heat Pump Program

• City of Seattle—Community Power Works Loan Program

• Clallam County PUD—Residential and Small Business Efficiency Loan Program

• Clallam County PUD—Residential and Small Business Solar Loan Program

• Clark Public Utilities—Residential Heat Pump Loan Program

• Clark Public Utilities—Solar Energy Equipment Loan

• Grays Harbor PUD—Residential Energy Efficiency Loan Program

• Grays Harbor PUD—Solar Water Heater Loan

• Port Angeles Public Works & Utilities—Solar Energy Loan Program

• Richland Energy Services—Residential Energy Conservation & Solar Loan Program

1http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=US02F&re=1&ee=1.

2http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=US52F&re=1&ee=1.

3id.

4id.

5http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=US05F&re=1&ee=1.

6http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=US56F&re=1&ee=1.

7http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=US48F&re=1&ee=1.

8http://energycenter.org/index.php/public-affairs/federal-legislation/1283-qualified-energy-conservation-bonds-qecbs.

9http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=US51F&re=1&ee=1.

10Established in 1995, DSIRE is currently operated and funded by the NC Solar Center at NC State University, with support from the Interstate Renewable Energy Council, Inc. DSIRE is funded in part by the US Department of Energy. DSIRE data provides the basis for this section.

11Gouchoe, S., Everette, V., Haynes, R., 2002. Case Studies on the Effectiveness of State Financial Incentives for Renewable Energy. North Carolina Solar Center and National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Raleigh, NC.

12http://www.dsireusa.org/solar/solarpolicyguide/?id=13.

13http://www.dsireusa.org/solar/solarpolicyguide/?id=10.

14id.

15id.

16http://thesolarfoundation.org/research/national-solar-jobs-census-2012.

17http://www.dsireusa.org/solar/solarpolicyguide/?id=10.

18id.

19Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Clean Energy States Alliance, 2008. Property Tax Assessments as a Finance Vehicle for Residential PV Installations. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Clean Energy States Alliance.

20http://www.dsireusa.org/solar/solarpolicyguide/?id=26.

21http://www.dsireusa.org/solar/solarpolicyguide/?id=11.

22http://www.dsireusa.org/solar/solarpolicyguide/?id=14.

23http://www.dsireusa.org/solar/solarpolicyguide/?id=16.

24id.

25The Solar Foundation 2012 Solar Jobs Census.