Policy Roles, Responsibilities, and Accountability

It’s important to note that change is inevitable. The implementation of security policies is just one of a vast array of changes employees must absorb. Understanding this is important when creating security policy roles, responsibilities, and accountability. The closer you can align employees’ current roles with their current job responsibilities, the easier it will be to implement. For example, assume a security policy requires a certified security trainer for a specific team. Now assume that team already has a trainer for a nonsecurity purpose such as office safety. Combining these roles and responsibilities could create the opportunity to combine training requirements and make it easier for the business to accept the security policy.

Many players are involved in the process of security policy implementation. The roles and responsibilities are different depending on where you are in the life cycle of a security policy. The term life cycle in this chapter refers to the creation, implementation, awareness, and enforcement of security policies. These different tasks require different roles and responsibilities.

There are many theories on how to approach change and an individual’s role in the change process. The key point is to understand everyone’s role from the perspective of a change model. You need to clearly define everyone’s role when developing and changing policies. You also need to recognize different roles when it comes to enforcing policies after they have been implemented.

TIP

TIP

When you implement security policies, you are implementing change. This can include implementing business perspectives and organizational values. This means sometimes you are implementing culture change as much as security controls. Be sure to select a change management model that speaks to the need to influence leaders as much as to technical implementation of controls.

Change Model

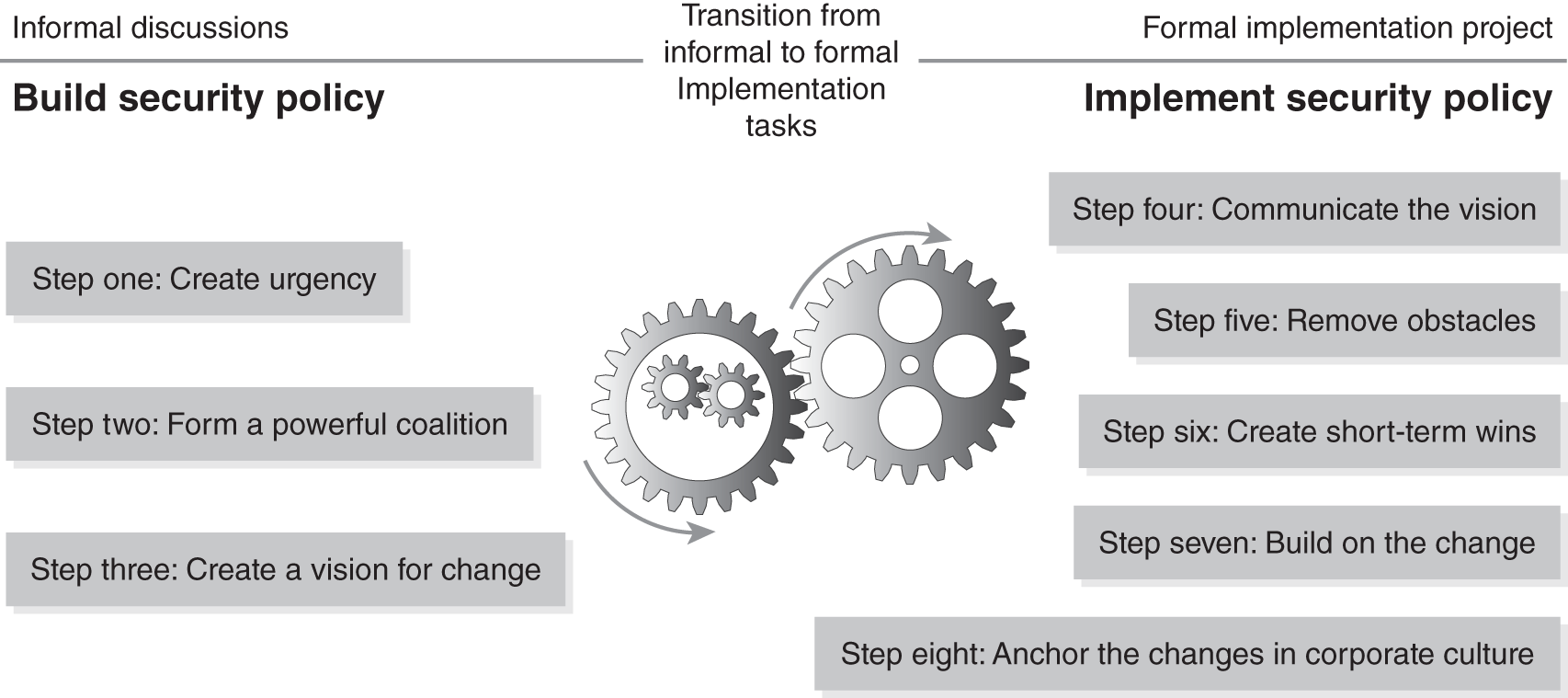

There are many change models to choose from. You may be able to adapt some when implementing security policies. This section focuses on Kotter’s Eight-Step Change Model. John Kotter, a professor at Harvard Business School, developed the model and introduced it in 1995 in a book titled Leading Change. The model has been widely adapted for a number of purposes. It addresses the need to create executive support for implementing change. This is a critical success factor in implementing security policies.

Professor Kotter states that to be successful in implementing change in a company, at least 75 percent of management needs to “buy into” it. The early stages of creating vision and urgency around the need for security policies will be critical later to build the coalition of executives needed to make change happen.

Let’s examine the model in relation to implementing security policies. The model divides an effective change process into eight steps:

- Create urgency—For change to happen, there must be an urgent need. Helping people understand information security threats and risk to the business can help build this sense of urgency.

- Form a powerful coalition—For change to happen, leadership must back you. Establish early a tone at the top for the need for the security policy.

- Create a vision for change—Change needs to be understandable. It must be clear what you are asking of people and what measurable benefit the security policy will bring.

- Communicate the vision—Once you have support, you need to communicate your intent widely. Communicate the security message through as many channels as possible.

- Remove obstacles—There will be barriers to your success. Empower individuals to be change agents. A change agent is someone tasked with challenging current thinking.

- Create short-term wins—Success, no matter how small, breeds more success. Focus on small, well-defined goals that collectively build toward larger long-term goals.

- Build on the change—Real change takes time and continued effort. Build a process of continuous improvement of the security policies.

- Anchor the changes in corporate culture—To make anything stick, it must become habit and part of the culture. Find opportunities to integrate security controls into day-to-day routines.

FIGURE 5-6 shows how this model can be adapted to implementing security policies. You would cycle through this model each time you add a new security policy or make a major change to an existing policy. This model ensures that before you start a formal implementation, you have the leadership support needed to succeed. It also highlights the separation between informal and formal tasks. When we adapted Kotter’s model for the purposes of this chapter, we created a separation between informal and formal implementation tasks. This is to emphasize the importance of preparing for policy implementation through informal discussions versus starting a formal project approach right away. There are two major benefits to having these informal tasks. First, you gain executive support. Having a formal project before you have executive support is presumptuous and will create unnecessary resistance. Second, it establishes a collaborative setup that allows you to change and modify your approach. It also builds ownership into the process for the executive giving you advice.

FIGURE 5-6 Basic policy implementation approach.

Responsibilities During Change

Implementing security policies is easier if you manage it from a change model perspective. It helps you establish a collaborative style that allows business leaders to understand and buy into what you are trying to accomplish. The process starts with an informal set of steps that builds awareness and understanding. With a clear purpose beyond your security policies, you can build the executive support needed to succeed.

Using the steps in Kotter’s Eight-Step Change Model, the following sections explain the roles and responsibilities involved in the change process.

WARNING

WARNING

Be candid and transparent with leaders. Explain clearly what information security policies can and cannot achieve. Equally important, be upfront about the impact on the business; otherwise, you risk losing credibility.

Step 1: Create Urgency

It is the responsibility of the CISO, who may simply be called the information security officer (ISO), to convey urgency to business leaders. This is selling the need for information security. An effective way of doing this is to understand the business risk the security policy addresses and convey the need in business terms. The greater the business risk reduction, the greater the urgency perceived by the business.

Step 2: Create a Powerful Coalition

It’s important to get executive support. Leaders are responsible for reducing risk to their organization. It’s the responsibility of the ISO to know who the key stakeholders are. It’s also the responsibility of the ISO to reach out to stakeholders, explain the policy change, and listen to concerns. Many organizations have what are called control partners. It’s the responsibility of a control partner to offer an opinion on the soundness and impact of the security policy. Many organizations require control partners’ input before a policy change can be made. The following are examples of control partners found in many large organizations:

- Internal auditors

- Operational risk managers

- Compliance officers

- Legal professionals

The size of the stakeholder group varies depending on the scope of the policy change and the size of the organization. When the number of stakeholders in any group is too large, the ISO can take a sampling approach. For example, assume a policy change affects the entire organization, which is composed of more than 1000 managers. It’s not practical to ask each manager how the policy would affect every team. Therefore, the ISO would sample a population of managers. The ISO can target those types of managers who would be more affected than others.

Step 3: Create a Vision for Change

The security policy must be understandable. It is the ISO’s responsibility to write the policy in terms the business understands. The ISO can tune the message so the value of implementing the policy makes sense. After compiling everyone’s input, the ISO creates a coherent security message and policy. The message should include high-level explanations of the policy to sell the vision. It is the responsibility of the stakeholder to validate the ISO’s assumptions and raise objections.

It’s not appropriate for a stakeholder to wait until just before a security policy is implemented to object. The ISO is responsible for ensuring all objections are transparent and either resolved or escalated. The ISO must make every effort to resolve an objection. The objection could be pointing out a legitimate problem that requires a change to the security policy or control.

It might not be possible to make everyone happy; however, everyone needs to have a say. Remember, success depends on a genuine effort to implement the spirit of the policies. Everyone reports to someone in an organization. It is the ISO’s role to escalate conflicts to some authority who can resolve them. In the end, you are trying to get the majority of leaders on your side.

TIP

TIP

Find a leader in your organization who can be an agent of change. These are leaders who don’t always follow the pack and can think outside of the box. They can guide you through the organizational politics involved in implementing change.

Step 4: Communicate the Vision

The policy change must be widely communicated. It is the ISO’s responsibility to create the message. The ISO must also formally lay out communication plans. A communication plan outlines the messages to be conveyed, how they will be conveyed, and to whom they are conveyed. Communication starts before the policy is published. For example, establishing a comment period for a new or changed policy can generate awareness. The ISO also needs to transition the implementation of security policies from informal discussions to a formal project plan. The project plan needs to outline dates, timelines, resources, and organizational support needed to be successful.

Stakeholders, particularly executive leaders, are responsible for communicating the change with their endorsement. Whether a leader raised an objection or not, leaders have an obligation to communicate and endorse any approved policy. This tone at the top is an important responsibility for an executive to perform. Executives are also responsible for setting team priorities to implement security policies.

TIP

TIP

The collateral created to sell the policy vision should be used in security awareness training. It will express the business need for the policy as well as the technical security components.

Step 5: Remove Obstacles

Obstacles to implementation must be identified and removed. It is the ISO’s responsibility to be the central point of contact and to track implementation problems. It is the stakeholder’s responsibility to collect and report problems with the implementation. It is everyone’s responsibility to report problems with security policies to their leadership. Many information security teams set up intranet sites so security issues can be reported directly to the security team.

Step 6: Create Short-Term Wins

It’s important to demonstrate value as early as possible. The ISO is responsible for identifying how success is measured. The ISO works with line management to collect metrics for assessing the policies’ effectiveness. It is usually the responsibility of these line managers to make sure such metrics are captured and are meaningful.

Step 7: Build on the Change

It takes time to change an organization’s culture. The ISO must continually monitor security policy compliance. The ISO reports to leadership on the current effectiveness of the security policies. The ISO will also have to ask the business to accept any residual risk or come up with a way to reduce it. Residual risk is the amount of risk that remains after you implement security controls. For example, let’s assume a virus scanner can catch 99 percent of all known viruses. That leaves 1 percent of the viruses undetected. The business needs to know about this risk. The business leaders are then responsible for accepting this risk or paying for more technology to stop the remaining 1 percent.

Step 8: Anchor the Changes in Corporate Culture

Make the values in the security policies part of the culture. This takes time and is achieved by changing employees’ attitudes. The ISO needs to be a strong communicator. It is his or her responsibility to come up with ways to reinforce the security message without creating a distraction for the business.

Roles and Accountabilities

The organization is ultimately accountable for information security. When something catastrophic occurs, with lawyers and regulators engaged, the organization’s leaders have to explain what happened. In fact, officers of the organization may be held personally liable. They may pull the top technology executive (the CIO) along for the ride. But executives are the ones who fund technology and determine how much risk they are willing to pay to reduce.

Setting expectations for leaders quickly becomes a matter of budget. If there aren’t dollars to spend to implement controls, then it’s hard to hold executives accountable. IT spending varies greatly by industry. Deloitte found that on average, companies spend 3.28 percent of their revenue on IT. This percentage changes if you focus on specific industries. Banks tend to spend around 7.16 percent and construction 1.51 percent. Of those companies that consistently outperform the S&P 500, 57 percent increased their IT budget from 2016 to 2017.1 Companies that spend more on IT have more resources to deploy for information security. Thus, the expectations for information security in a financial services company may be different from those in a manufacturing company.

Although business leaders may be ultimately responsible, they rely on key technology roles to keep them out of trouble. These roles are accountable for implementing security policies, monitoring their adherence, and managing day-to-day activities. Although their titles may vary within an organization, typically you find different individuals accountable for each of the following roles:

- Information security officer (ISO)—The individual accountable for identifying, developing, and implementing security policies. The ISO is also accountable for ensuring that corresponding security controls are designed and implemented.

- Executive—A senior business leader accountable for approving security policy implementation. An executive is also responsible for driving the security message within an organization and ensuring the security policy implementation is given appropriate priority.

- Compliance officer—An individual accountable for monitoring adherence to laws and regulations. A compliance officer often uses adherence to security policies as a measure of regulatory compliance.

- Data owner—Typically someone in the business who approves access rights to information. Data owners are accountable for ensuring only the access that is needed to perform day-to-day operations is granted. They would also be responsible for ensuring there is a separation of duties to reduce risk of errors or fraud.

- Data manager—An individual typically responsible for establishing procedures on how data should be handled. Data managers also ensure data is properly classified.

- Data custodian—An individual responsible for the day-to-day maintenance of data. Data custodians back up and recover data as needed. They grant access based on approval from the data owner. You can view their accountability as generally maintaining the data center and keeping applications running.

- Data user—The end user of an application. Data users are accountable for handling data appropriately. They are accountable for understanding security policies and following approved processes and procedures. Data users have an obligation to understand their security responsibilities and not to violate policies.

- Auditor—An individual accountable for assessing the design and effectiveness of security policies. An auditor can be internal or external to the organization. They offer formal opinions in writing. These opinions review the completeness of the policy design and how well it conforms to leading industry practices. Auditors also offer opinions on how well the policies are followed and how effective they are. Auditors do not report to the leaders they are auditing. This allows them to provide a valuable independent second opinion. For example, internal auditors in publicly traded companies typically report findings to the audit committee and line management. External auditors may issue findings to executive management and the audit committee. The audit committee is a subcommittee of the board of directors.

ISOs need to make sure they build security policies collaboratively. The key is to create an open and candid conversation on risk. If the discussions on risk are perceived as valuable, executives are more willing to commit their time. This means the ISO needs to hold stakeholders accountable to participate. No one should be able to opt out. Accountability changes once the security policies are implemented. End users are accountable for following policies. The ISO’s central role is to coordinate these activities.