Chapter 9. Understanding E-mail and Internet Crimes

Introduction

A number of tools are used to access resources on the Internet, and each of them can be used to commit a crime or potentially become a victim. By accessing the Internet, e-mail clients and Internet browsers can expose computers to viruses and spam, and can expose the people using those computers to various forms of cybercrime.

The Internet is widely used as a source of information and enjoyment, but it is as susceptible to crime as any community. There are online predators who attempt to coerce or seduce children into having sex, and child pornography is rampantly downloaded and traded online. These images may be acquired using home computers or in the workplace. Just as hackers can access systems and cause damage, so can terrorists. Cyberterrorism can involve damaging key systems, accessing sensitive intelligence, or performing other acts that could cause harm on a widespread level.

In this chapter, we'll look at a wide range of tools that are used to access illegal materials and expose victims to cybercriminals and illegal materials. Obviously, the most common tools used on the Internet are e-mail clients and Internet browsers. E-mail clients are used to send and receive messages, and they can be used as a source of evidence to see who a person has contacted, what was said, and what files were sent and received by that person. Internet browsers allow people to access both legitimate and illegal materials, and can expose a machine to a wide range of threats. As such, we'll look at how poor security in Internet browsers can be exploited, and simple measures to secure the browser.

Understanding E-mail and E-mail Forensics

E-mail is short for “electronic mail,” and it is used to send messages to others on the Internet. According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project, in a February–March 2007 survey, 71 percent of American adults use the Internet and 91 percent of them send or read e-mail. Because sending an e-mail is more common today than writing a letter was a few decades ago, it should come as no surprise that e-mail is also used for illegal purposes.

Most people send and receive e-mails using e-mail client software such as Microsoft Outlook, Outlook Express, Thunderbird, Eudora, or others. These programs are installed on a computer, and they store the messages in files on the local hard disk. Online services, including free e-mail services, are also available, in which a person accesses his or her e-mail through a Web site. These messages are stored on the e-mail service's servers. Some of the most popular services include Hotmail (www.hotmail.com) and Gmail (http://mail.google.com). More secure services such as Hushmail (www.hushmail.com) are also available that will encrypt messages before they're sent.

E-mail Terminology

Before you can start to examine e-mail archives, you have to understand the special language that is used when talking about e-mail. Just like the police and other professions use acronyms in everyday jargon, e-mail technology has unique words that are used to describe the smaller-scale ingredients of an e-mail. These terms include the following:

▪ IMAP Internet Message Access Protocol is a method for accessing e-mail or bulletin board messages that are kept on a mail server, making them appear and act as though they were stored locally.

▪ SMTP Simple Mail Transfer Protocol receives outgoing mail from clients and validates source and destination addresses. It also sends and receives e-mail to and from other SMTP servers. The standard SMTP port is 25.

▪ HTTP Hypertext Transfer Protocol is typically used in Web mail and the message remains on the Web mail server.

▪ ESMTP Enhanced SMTP is a set of protocol extensions to the SMTP standard.

▪ POP3 Post Office Protocol 3 is a standard protocol for receiving e-mail that deletes mail on the server as soon as the user has downloaded the e-mail. The standard port for POP3 is 110.

▪ Cc Carbon Copy is a field in the e-mail header that directs a copy of the message to go to another recipient e-mail address.

▪ Bcc Blind Carbon Copy is a field that is hidden from the receiver but allows for a copy of the message to be sent to the e-mail address in this field.

▪ HELO This is a communication command from the client to the server in SMTP e-mail delivery.

▪ EHLO This is the HELO command in ESMTP clients.

▪ NNTP Network News Transfer Protocol is used for newsgroups similar to standard e-mail. Headers are usually downloaded first in groups. The bodies are downloaded when the message is opened.

Each of these items will help you to understand e-mail, and they provide an easy reference for some of the topics we'll discuss in the sections that follow.

Understanding E-mail Headers

There's more to managing information security than dealing with boundary devices and various types of logs. E-mail can open the doors for all kinds of attacks and infections in an organization. Besides making sure to install and use antivirus (AV) software that inspects all e-mail payloads (and hopefully blocks all potential sources of such attacks), it's also necessary for users and administrators to deal with unsolicited e-mail (also called spam) or with e-mail-based denial-of-service (DoS) attacks (so-called mail bombs). To deal properly with spam and e-mail-based DoS attacks, it's absolutely essential to understand how to read e-mail headers. Such knowledge will not only permit administrators and investigators to determine at least a putative (if not the actual) source for the attack or spam, but it will also help them to define a strategy for dealing with such behavior.

The ability to track e-mail messages is important in many different types of cybercrime cases. It is not unusual for criminals to use e-mail in the following ways:

▪ To harass victims (cyberstalking)

▪ To send extortion demands or threats

▪ To solicit “marks” for con games (Nigerian scam, pyramid schemes)

▪ To coax people to visit Web sites and provide personal information that can be used for identity theft and other purposes (phishing)

▪ To communicate with accomplices

In all of these situations and others, e-mail may be one (or the only) clue to the criminal's identity and may become evidence at trial. Unless the criminal is kind enough to sign the message with a full (and accurate) name, address, and phone number, the only way to determine where a message originated is to examine the message “headers.” E-mail generally goes through a number of different computers on the way from the sender to the intended recipient. Header information is added to the message at each machine along the way, until it reaches its destination. (The workstation on which the recipient reads the mail generally doesn't add header info.) It is important for investigators to know what information can—and can't—be discerned from e-mail headers and to understand that headers can be spoofed (forged).

Breaking down and understanding e-mail headers requires some knowledge of how to recognize and decode the fields in those headers. This level of structure is well documented and is primarily defined in Request for Comments (RFC) 822, which documents the layout and structure of SMTP message header fields. Although there are more fields than the ones we discuss here, Table 9.1 lists the most important fields as well as all the fields you'll need to check to try to trace messages back to their origins and to identify the route they took from their putative original sender to reach the recipient's e-mail server.

The fields of greatest interest when dealing with malicious e-mail or spam are those that identify the putative sender (From, Reply-to, Sender, Return-path, and so forth), as well as all the various received fields that indicate the mail servers involved in routing the message(s) from the sender to your server. Although those Received lines that don't include a From field do not actually identify a sender, users can report that spam is being routed through those servers to the Internet service providers (ISPs) or organizations that operate them. In many cases, the provider will be able to filter out the unwanted e-mail rather than forwarding it to the complaining user or some other hapless victim. In fact, it's best to concentrate on the Internet Protocol (IP) address reported on these lines, because clever e-mail attackers can forge much of this information. For more information on dealing with unwanted e-mail, including detailed instructions on creating and issuing spam complaints to forwarding server operators, see the excellent article “Reporting SPAM” at www.freelabs.com/~whitis/spam_reporting.html. (This site also contains a useful Links section with further pointers to spam investigation and reporting.)

Unfortunately, e-mail messages are far too easy to spoof, in the sense that knowledgeable individuals can either use software tools or construct entirely bogus RFC 822 e-mail headers by hand. Thus, not all reports of unwanted forwarding may produce the desired results of eliminating or reducing unwanted mail traffic. Some service providers operate special e-mail services known as anonymous or pseudo remailers. These so-called “anonymizer” services are deliberately designed to shield users from outright or personal identification; many operate outside the United States.

Dealing with Anonymizer Service Providers

In some cases, the companies or organizations that operate anonymizer services will respond favorably to requests for assistance from law enforcement professionals who seek to identify their customers who are using the service for criminal purposes. In other cases, a company may refuse to cooperate in any way at all; such lack of cooperation is more likely to occur when anonymizer service providers operate offshore. Nevertheless, some of the most notorious anonymizer services (for example, anon.penet.fi, originally based in Finland) have ceased operation, primarily in response to frequent repeated requests to identify their customers to law enforcement professionals all over the world. An old Internet saying applies when seeking cooperation from anonymous remailers: YMMV (“Your mileage may vary”). This is a polite euphemism for the very real situation in which things do not work exactly as described or advertised, or assistance with (or from) a service may simply not be available. It's worth a try (or a warrant, where one can be obtained), but seeking cooperation from these services may not always produce the desired results!

For more information about e-mail header fields and how to interpret them, consult the text for RFC 822 at www.faqs.org/rfcs/rfc822.html, or the article “Reading Email Headers” on the StopSpam Web site at www.stopspam.org/email/headers/headers.html. You'll also find valuable e-mail resources online at http://everythingemail.net and through the Internet Mail Consortium at www.imc.org.

Looking at E-mail Headers

Many e-mail programs don't show the full e-mail headers by default in the message, but you can view the headers if you drill down through the interface. In Outlook Express, you can view e-mail headers by right-clicking on a message in the message list, and then clicking on the Properties menu item in the context menu that appears. As shown in Figure 9.1, clicking on the Details tab allows you to view the e-mail headers associated with that message. In looking at the information in the header, please note that the e-mail addresses have been changed to fictious ones. To view the full HTML code in the e-mail message, you could then click on the Message Source button.

|

| Figure 9.1 A Microsoft Outlook Express E-mail Header |

If this message were part of a mail bomb attack or spam, you'd want to contact the operators of the various servers identified in the Return-path and From fields, and inside the various Received fields in the header. But first, it would also be useful to employ the whois command at your command line to check the domain names reported against the IP addresses used. Whois allows you find out to whom a domain name is registered.

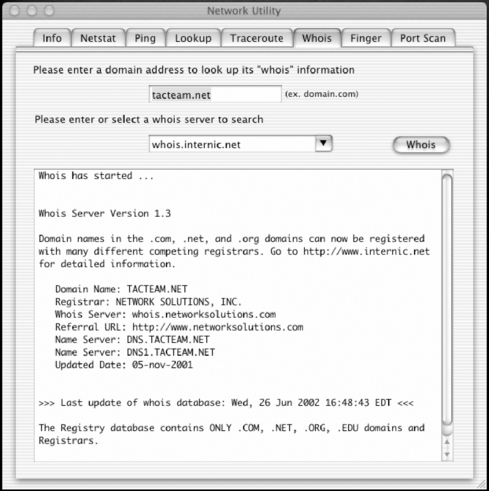

Windows does not typically include built-in whois capabilities, but numerous sources for Windows-compatible whois utilities are available, such as those at www.tatumweb.com/iptools.htm. Or you can use the services at www.samspade.org to perform the necessary lookups through its Web pages without using a whois tool on your Windows PC. Likewise, if you have access to a UNIX shell account, you should be able to use the whois command at the command line. Mac OS X has a useful graphical version of whois, as shown in Figure 9.2.

|

| Figure 9.2 The Mac OS X Graphical Whois Utility |

E-mail Forensics

Numerous e-mail recovery and e-mail forensic tools are available to view the files where e-mails are archived on a hard disk. For example, e-mail is stored in .dbx files, and those files are named after the folder in which the e-mails are stored (that is, Inbox.dbx, Deleted Items.dbx, and so on). Typically, you would create a traditional bitstream image of the entire drive and then extract these files from the drive image. Many good virtual mounting programs are available that allow you to mount the image file and extract a copy of the data from that drive. Some of the e-mail forensic and recovery tools available include the following:

▪ Paraben's E-mail Examiner Designed to process a wide variety of active and deleted e-mail archives. This includes Outlook Exchange, Outlook Express, Eudora, Pegasus Mail, EML message files, and many others.

▪ Paraben's Network E-mail Examiner (NEMX) Can be used to process Microsoft Exchange archives as well as Lotus Notes and GroupWise files. Built into the tool is a corruption repair utility that will also save some time in processing by attempting to bypass corruption and move on to read the rest of the archive, allowing you to keep the data in its original state.

▪ Ontrack PowerControls A tool for copying, searching, recovering, and analyzing e-mail and other mailbox items from Microsoft Exchange server backups, Information Store files, and unmounted databases (EDB).

Tracing a Domain Name or IP Address

The domain name system (DNS) is responsible for maintaining domain-name-to-IP-address mappings on the Internet. Numerous boundary devices, such as firewalls and screening routers, can perform reverse DNS lookups to make sure that reported domain names match actual IP destination addresses in inbound traffic. When these do not match up properly—that is, when looking up the domain name produces an IP address that is different from the one in the destination address—the sender may be attempting to spoof a domain name without making sure the IP address matches. This is a sign of a less-than-savvy hacker. Hackers who know what they're doing generally make an effort to match the IP addresses from which they claim to originate with the domain names they use.

Nevertheless, the “reverse DNS lookup” technique permits a device to query the DNS server for an IP address to go along with a domain name, as well as to perform the more standard name-to-address translations that DNS typically provides whenever a computer attempts to connect to another machine using a “friendly” DNS name instead of the IP address. You can configure most boundary equipment, and many IP servers, to perform a reverse DNS lookup before granting access even to anonymous users, and to deny access to users whose reported domain names and IP addresses don't match up. Although this is not an entirely foolproof technique for blocking spoofed traffic completely, it is highly recommended for networks that permit traffic to enter from outside their local networks (especially from the Internet).

In general, DNS queries that use reverse lookup work backward through the IP address to the domain name, using a special file on the DNS server called in-addr-arpa. For example, if a Web server has an Internet address of 206.224.64.194, the lookup proceeds in reverse order into a file named 64.224.206-in-addr-arpa on some DNS server where individual addresses on that subnet can be resolved (such as the Web server named www.lanw.com at 206.224.64.194). Most network boundary devices and servers perform such lookups automatically and write them to their log files. Nevertheless, investigators should also know how to get from domain names to IP addresses and from IP addresses to domain names manually, if only to confirm the results they find in firewall, router, or server log files.

Table 9.2 summarizes key commands you can use to obtain domain name and IP address-related information. Rather than providing complete syntax information, we provide pointers to Windows and UNIX/Linux commands, with help files where you can find such details and numerous examples. Please note also that www.tatumweb.com/iptools.htm offers access to numerous Web-based lookup tools with the same functionality. The benefit of this latter approach is that you can simply enter a domain name or IP address and other arguments as needed, and observe the results without mastering the underlying command syntax or details.

Note

A useful Web site for obtaining DNS information is at www.dnsreport.com. Administrators can use it to find out about problems and vulnerabilities with their DNS servers.

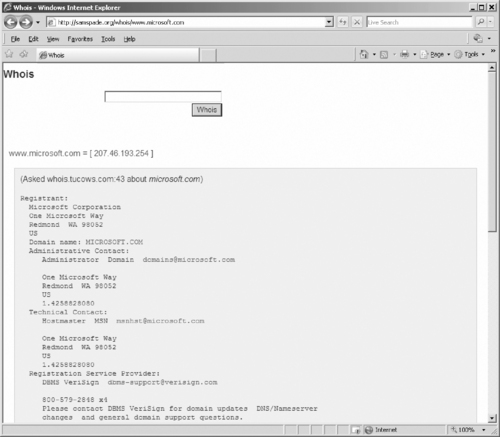

The tools listed in Table 9.2 are vital to properly investigating the source of an e-mail or the owner of a Web site. By using the whois tool at www.samspade.org, we could enter the URL of a Web site and get information that was provided when the domain name was registered. As shown in Figure 9.3, the results of entering the URL www.microsoft.com produce the name and address of the registrant, contact e-mail, and other information that can be useful in an investigation.

|

| Figure 9.3 Whois Output for www.microsoft.com |

Similarly, by performing a reverse lookup using Nslookup or using whois to identify the owner of a mail server (found in the header of an e-mail), an investigator could then request or serve the ISP with a warrant to provide account information on the person who sent the e-mail. For example, by viewing the e-mail header and seeing the IP address from which the e-mail was received, you can then use the Nslookup.exe tool in Windows or an online Nslookup tool such as the one at www.zoneedit.com/lookup.html to view the contact information for the ISP to which the IP address is registered. The ISP can then check its logs to see to whom the IP address was issued when the e-mail was sent.

Understanding Browser Security

No matter what type of Internet connection a company or individual uses, whether broadband, dial-up, or local area network (LAN), it is important to address the security vulnerabilities that Web browsers introduce to the systems and network. Many of the most commonly used Internet service client software programs, such as Web browsers and e-mail utilities, are vulnerable to an ever-expanding list of malicious attacks. Most of these attacks are made possible by the dynamic and automated capabilities that these tools have acquired over the years. The inclusion of scripting and programming languages in these utilities (for example, JavaScript, Java, and ActiveX) has introduced new and easily exploited security vulnerabilities to an already imperfect environment. In an effort to maintain browser market share by offering the widest range of capabilities and features, Microsoft's Web browser Internet Explorer and e-mail clients Outlook and Outlook Express have become immensely popular and consequently are the most commonly attacked Internet service clients.

It is important to remember that Microsoft is not the only vendor whose Internet service products are susceptible to attacks—it's merely because this company's products are the most popular that they have become the favorite target of attackers. Some users—including networking professionals who should know better—operate under a false sense of security because they use non-Microsoft products. Each time a security flaw in Internet Explorer, Outlook, or a Microsoft operating system is announced, they proudly boast that they would never use such an insecure product. Meanwhile, a Web search for UNIX or Linux security vulnerabilities turns up thousands of pages detailing security holes in various UNIX/Linux versions. It bears repeating that there is no truly secure network-connected computer.

When it comes to Web browsers, the truth is that any utility that supports the execution of scripts or programming code downloaded from a Web page or an e-mail message is vulnerable. This includes not only Internet Explorer, but also other browsers such as Firefox, Opera, Safari, and so on. The proliferation of these vulnerabilities is the result of pursuing functionality in hopes of obtaining market share instead of thoroughly investigating and dealing with the security implications.

Most vulnerabilities found in Web and e-mail clients relate to buffer overflow errors or arbitrary code execution. Both of these vulnerabilities enable a remote system, whether a Web site or a sender of an e-mail message, to execute malicious code on your computer. In most cases, the executed code is granted system-level privileges, meaning that there are literally no restrictions on what actions such code can take.

The same technologies that create vulnerabilities in Web browsers can also be used in HTML e-mail. Many popular e-mail clients, including Outlook and Outlook Express, allow active content to run, leaving a system open to malicious coders.

Securing E-mail Clients

The following Web resources give you more specific information about securing various e-mail clients:

▪ Outlook/Outlook Express: http://antivirus.about.com/library/bloutlook.htm

In the next sections, we look at the technologies that create security risks in Web browsers and e-mail, and then we discuss how to make each of the popular browser programs more secure.

Types of Dangerous Code

Several different types of code can be used to enhance Web pages and e-mail and to perform unwanted and even dangerous actions on a computer. The following sections provide an overview of the most popular of these types of code: JavaScript, ActiveX, and Java.

JavaScript

JavaScript is a scripting language developed by Netscape to allow executable code to be embedded in Web pages. All major Web browsers support JavaScript. JavaScript is used to manipulate browser window size, open and close windows, manage forms, and alter browser settings. JavaScript itself is relatively secure. However, improper implementations (such as vendor programming errors) have enabled numerous attacks. Each vendor has patched most of these vulnerabilities, but it is still possible to use JavaScript to perform a malicious activity if you can trick Web surfers into doing something they shouldn't. Unfortunately, it is usually easy for a malicious Web site to trick visitors into providing access or enabling code execution when they shouldn't.

ActiveX

ActiveX is a code-embedding technology developed by Microsoft. It employs a security control known as code signing. Each ActiveX program is called a control. When a control is downloaded to a Web browser, it is scanned for a digital signature using the Authenticode technology to verify the signature with a certificate authority (CA) and ensure that it hasn't been altered before downloading the control. A dialog box is displayed, indicating that the ActiveX control is signed by a specific company or individual and prompting the user to indicate whether to accept this control, always accept controls from this entity, or deny this control. Once an ActiveX control is on a system, it can do anything it is programmed to do, whether benign or malicious. Just because you know who are the authors of a control doesn't guarantee that the control is secure or that its interactions with other controls will not introduce new vulnerabilities to your system.

Java

Java is a programming language developed by Sun Microsystems. It is fundamentally different from JavaScript in that it uses a technique known as sandboxing to restrict its capabilities. Java programs that execute locally are called applets. Each applet is checked to make sure it is coded properly and is not corrupted before it is allowed to execute. Then a security monitor oversees the applet's activity to prevent it from performing actions that it should not be able to perform, such as reading data, opening network connections, or deleting files.

Unfortunately, some implementations of Java have been compromised using various exploits. Hostile applets can also crash browsers and systems, kill other applets, extract your e-mail address and send it to the applet's distributor, and perform other nasty acts.

Making Browsers and E-mail Clients More Secure

Network administrators and users can take several steps to make Web browsers and e-mail clients more secure and protect against malicious code or unauthorized use of information. These steps include restricting the use of programming languages, keeping security patches current, and becoming aware of the function of cookies.

Restricting Programming Languages

Most Web browsers have optional settings that allow users to restrict or deny the use of Web-based programming languages. For example, Internet Explorer can be set to always allow, always deny, or prompt for user input when a JavaScript, Java, or ActiveX element appears on a Web page. Restricting all executable code from Web sites, or at least forcing the user to make choices each time such code is downloaded, reduces security breaches caused by malicious downloaded components.

A side benefit of restricting these programming languages for a Web browser is that those restrictions often apply to the e-mail client as well. The same malicious code that can be downloaded from a Web site could just as easily be sent to a person's e-mail account. If you don't have such restrictions in place, your mail client could automatically execute downloaded code.

Keeping Security Patches Current

New exploits for Web browsers and e-mail clients seem to appear daily. Product vendors usually address significant threats promptly by releasing a patch for their products. To maintain a secure system, you must remain informed about your software and apply patches for vulnerabilities when they become available.

However, you must consider a few caveats when working with software patches:

▪ Patches are often released quickly, in response to an immediate problem, so they may not have been thoroughly tested. This can result in failed installations, crashed systems, inoperable programs, or additional security vulnerabilities.

▪ It is extremely important to test new patches on nonproduction systems before deploying them throughout your network.

▪ If a patch cannot be deemed safe for deployment, you should weigh the consequences of not deploying it and remaining vulnerable to the threat against the possibility that the patch might itself cause system damage. If the threat is minimal, it is often safer to wait until you experience the problem a patch is designed to address before deploying such a questionable patch.

Cookie Awareness

A cookie is a kind of token or message that a Web site hands off to a Web browser to help track a visitor between clicks. The browser stores the message on the visitor's local hard disk in a text file. The file contains information that identifies the user and his or her preferences or previous activities at that Web site. If the user revisits the same Web site, the user's browser sends the cookie back to the Web server. Cookies are extremely useful in allowing a Web site to provide a seemingly continuous communications session with a visitor, such as maintaining a shopping cart, remembering search keywords, or customizing displayed data based on the user's preferences. However, because cookies contain identifying information, they might be used for less noble purposes.

Cookies have been discussed extensively in the popular press. These stories sometimes grant cookies more power than they really have and assign them more regard than they deserve. Cookies raise questions about privacy, but they are unable to execute code or access files. Instead, cookies simply store data from Web browsing sessions and send that same data back to a Web server. Cookies can be delivered to a computer via Web pages or HTML-enabled e-mail. Malicious, or at least unscrupulous, use of cookies occurs when they are used to track a user's surfing habits from one system to another, to grab a user's logon information from one site and send it to another, or even to capture a user's e-mail address and add the user to mailing lists without the user's knowledge. Fortunately, cookies can be disabled in the same manner as programming languages.

Securing Web Browser Software

Although the same general principles apply, each of the popular Web browser programs has a slightly different method to configure its security options. Securing Web browser software involves applying the latest updates and patches, modifying a few settings, and practicing intelligent surfing. Microsoft seems to release an Internet Explorer-specific security patch just about every week. This constant flow of patches is due to both the oversights of the programmers who wrote the code and the focused attacks on Microsoft products by the malevolent cracker community. In spite of this negative attention, you can still employ Internet Explorer as a relatively secure Web browser—when it is configured correctly.

The first step in securing Internet Explorer is to install the latest patches and updates. Users can do this automatically through Windows Update, or they can do it manually. Either way, only through patch application will most of the known vulnerabilities of Internet Explorer programming be resolved.

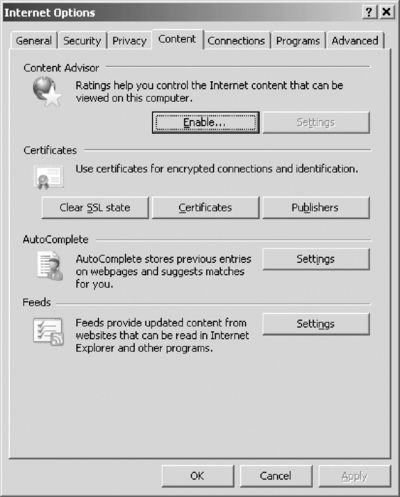

The second step is to configure Internet Explorer for secure surfing. Users can do this through the Internet Options applet. In Internet Explorer 7, you can access this applet through the Windows Control Panel or through the Tools menu of Internet Explorer. If the default settings are altered on the Security, Privacy, Content, and Advanced tabs, as shown in Figure 9.4, Internet Explorer security is improved significantly.

|

| Figure 9.4 Settings on the Security Tab in Internet Explorer's Internet Options, Used to Define Security Zones |

Zones are defined on the Security tab. A zone is nothing more than a named collection of Web sites (from the Internet or a local intranet) that can be assigned a specific security level. Internet Explorer uses zones to define the threat level a specific Web site poses to the system. Internet Explorer offers four security zone options:

▪ Internet Contains all sites not assigned to other zones.

▪ Local intranet Contains all sites within the local intranet or on the local system. The operating system maintains this zone automatically.

▪ Trusted sites Contains only sites manually added to this zone. Users should add only fully trusted sites to this zone.

▪ Restricted sites Contains only sites manually added to this zone. Users should add any sites that are specifically not trusted or that are known to be malicious to this zone.

Each zone is assigned a predefined security level, or a custom level can be created. The predefined security levels are offered on a slide controller with a description of the content that will be downloaded under particular conditions. You can also define custom security levels to exactly fit the security restrictions of your environment. There are security controls related to how ActiveX, downloads, Java, data management, data handling, scripting, and logon are handled. The most secure configuration is to set all zones to the High security level. However, keep in mind that increased security means less functionality and capability.

The Privacy tab, shown in Figure 9.5, defines how Internet Explorer manages personal information through cookies.

|

| Figure 9.5 The Privacy Tab in Internet Explorer's Internet Options, Where You Can Set Cookie Options |

The Privacy tab offers a slide controller with six settings ranging from full disclosure to complete isolation. You can also define a custom set of cookie controls by deciding whether first-party and third-party cookies are allowed, are denied, or initiate a prompt, and whether session cookies are allowed. You can define individual Web sites whose cookies are either always allowed or always blocked. Preventing all use of cookies is the most secure configuration, but it is also the least functional. Many Web sites will not function properly under this setting, and some will not even allow you to visit them when cookies are disabled.

The Content tab, shown in Figure 9.6, gives you access to the certificates that Internet Explorer trusts and accepts. If you've accepted a certificate that you no longer trust, you can peruse this storehouse and remove it.

|

| Figure 9.6 The Content Tab in Internet Explorer's Internet Options, Where You Can Configure Certificate Options |

The Content tab also gives you access to Internet Explorer's AutoComplete capability. This feature is useful in many circumstances, but when it is used to remember usernames and passwords to Internet sites, it becomes a security risk. The most secure configuration requires that AutoComplete be turned off for usernames and passwords, that prompting to save passwords is disabled, and that the current password cache is cleared.

On the Advanced tab, shown in Figure 9.7, several security-specific controls are included at the bottom of a lengthy list of functional controls. These security controls include checking for certificate revocation, not saving encrypted pages to disk, deleting temporary Internet files when the browser is closed, using Secure Shell/Transport Layer Security (SSL/TLS), and warning when forms are submitted insecurely. The most secure configuration has all of these settings enabled.

|

| Figure 9.7 The Advanced Tab in Internet Explorer's Internet Options, Where You Can Configure Security Settings |

Another option that is available through the Advanced tab is turning on the Phishing Filter. Phishing is a method of tricking computer users to reveal personal information to fraudulent Web sites that appear authentic. When the Phishing Filter is enabled, Internet Explorer will analyze the sites you visit to check for features that are common to phishing sites. It will compare the address of a Web site to a list of sites, reported to Microsoft, which is stored on your computer. If the site is on the list, a warning will appear, notifying you whether the site has characteristics of a phishing site.

A final step in maintaining a secure Internet Explorer deployment is to practice safe surfing habits. Common sense should determine what users do, both online and offline. Unfortunately, as many law enforcement officers have observed in the course of their duties, common sense isn't all that common. Most of us wouldn't walk down a dark alley in the middle of the city at 3:00 a.m., but people do it—and unfortunately, they sometimes learn a lesson the hard way. Visiting Web sites of questionable design is the virtual equivalent of putting oneself in harm's way in a dark alley, but Internet users do it all the time. Here are some guidelines that should be followed to ensure safe surfing:

▪ Download software only from original vendor Web sites.

▪ Always attempt to verify the origin or ownership of a Web site before downloading materials from it.

▪ Avoid visiting suspect Web sites—especially those that offer cracking tools, pirated programs, or pornography—from a system that needs to remain secure.

▪ Always reject certificates or other dialog box prompts by clicking No, Cancel, or Close when prompted by Web sites or vendors with which you are unfamiliar.

Investigating Child Pornography and Other Crimes That Victimize Children

Child pornography is the sexually explicit depiction of anyone under the age of legal consent. When most people think of child pornography, which is also called kiddie porn, they think it relates to photos of prepubescent children involved in sexual activity. Although this is an example of child pornography, it can also include stories and other written passages, drawings, digitally manipulated images, video, or any number of other media. Also, because the legal definitions of a child and laws related to consent vary, a picture may be legal in one region or country and illegal in another.

In addition to child pornography, numerous other crimes have gained worldwide notice due to the Internet, thereby creating new terms to describe the crimes. Internet luring is the act of using a computer and the Internet to lure a child for sexual purposes. The people who accost children online are referred to as online predators, and they may even travel to other states or countries to visit children for the purpose of having sex. As we'll see in the sections that follow, a number of laws in different countries have been developed to protect children from exploitation. Because the Internet allows distribution of these materials across jurisdictions, this often requires law enforcement to work together and may require joint operations that are coordinated by government agencies or special projects that focus on eliminating child pornography, prosecuting offenders, and rescuing children.

Defining a Child

The age that a person progresses from childhood to adulthood varies depending on culture, religion, and legal designations. For example, in Jewish law, the age of maturity is 13 for a boy and 12 for a girl. However, Israeli law dictates that children cannot have consensual sex until 16, marry until 17, or reach the age of majority until 18. In looking at these ages, you can see that the differential of a child and adult varies dramatically. In terms of determining an age of consent for sexual activities, it can be even more convoluted.

Many people believe that the age of consent for sex is the same age used to determine whether a person is of legal age to pose or perform sexual acts in pornography. However, separate ages are often set for exploitive situations, such as prostitution and pornography. For example, although the legal age for consensual sex in Canada is 14, it is illegal to be in pornography until age 18. Similarly, although 12 is the minimum age for consensual sex in Mexico, a prostitute is underage if he or she is younger than 16. As you can see by this, the age in which a child is considered to be mature enough to handle sex or participate in sexually exploitive situations is neither agreed upon nor internationally recognized.

Note

You can view the latest information on ages of sexual consent at the World Ages of Consent for Sex and Marriage Web site at http://aoc.puellula.com/, or by visiting the Interpol Web page on sexual offenses against children at www.interpol.int/Public/ Children/SexualAbuse/NationalLaws/.

The varying ages of sexual consent have also caused another problem: child sex tourism, in which pedophiles travel to countries with low ages of consent to have sex with children, who are under the age of 18. A pedophile is someone whose primary sexual interest is in children. Some professionals make the distinction that pedophiles are interested in children and hebophiles are interested in adolescents; however, for the purposes of this chapter, we will use the term pedophile to refer to a person whose sexual interest is with a minor (that is, below the age of legal consent). Because such individuals are fearful of being arrested in their own country, they will travel to countries such as Thailand, where the legal age of consent is 13 and child prostitutes are plentiful. Even if a person is arrested in that country, often he or she can avoid prosecution by bribing officials.

Over the past few years, reforms in child exploitation laws throughout the world have established higher ages of consent, or in some cases have helped to establish an age of consent where there was none before. However, an international standard age of consent for areas of sexual consent, pornography, and other sexual exploitive activities is needed.

Understanding Child Pornography

Although we provided a clear definition of child pornography earlier, many countries have found it difficult to create a clear legal definition … or create any kind of legislation at all. In a report developed by the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children in 2006 (www.icmec.org/ en_X1/pdf/ModelLegislationFINAL.pdf), a review of 184 countries that were members of Interpol found that 95 countries had no legislation specifically addressing child pornography. Of those that did:

▪ Fifty-four countries had no definition of child pornography in their legislation.

▪ Twenty-seven countries didn't provide for computer-facilitated offenses (that is, digital images and media, and downloading or distributing over the Internet).

▪ Forty-one countries didn't criminalize the possession of child pornography.

Of the countries that do have laws that address these issues, child pornography is generally defined as having sexually explicit content. This may include such acts as lascivious exhibition of genitals, masturbation, fellatio, and/or cunnilingus (oral sex), intercourse, anal sex, or other graphic content. In countries where child pornography laws exist, it is generally illegal to possess, distribute, or produce such images or depictions. However, exceptions may exist if it is for specific circumstances, such as artistic or medical purposes. For example, a photo in a medical book may show a child's genitals, but would not be considered child pornography.

Child Pornography without the Pornography

Because of wordings in the law, some photos and depictions of children don't meet the legal definitions of child pornography. These photos are widely available on the Internet, and in art books and other media. In some cases, they are even available in mainstream bookstores.

Child erotica is a term applied to photos or depictions of naked children, which may or may not be also categorized as art. The images don't fall under standard definitions of pornography, as the photos of the children are natural poses and are not sexually explicit. In other words, there is no lascivious exhibition of genitalia, such as a child spreading his or her legs or posing lewdly. In many cases, the distinction between whether it is deemed as art is in the way it's presented.

Also, many sites on the Internet operate under the thin guise of promoting nudism, even though the images predominantly show teenage or prepubescent children. Many sites operate by charging money for access to more revealing images of children or the bulk of their photos. The photos are often taken at nudist resorts or other locations where nudity is legal, allowing amateur photographers to take photos of naked boys and girls without worry of immediate repercussions. By skirting the line between what is legal and illegal, these sites are able to operate.

Another type of photography that skirts the issue of child pornography is Web sites featuring child models. These child model or glamour sites feature young girls posing in bikinis, miniskirts, sheer lingerie, and other outfits. The photos of girls on such sites may not contain any nudity, but they are provocative and show scantily clad girls in suggestive poses. For good reason, such sites have undergone serious scrutiny over the past few years, with many being shut down.

Determining Whether Something is Legally Child Pornography

In the 1996 case United States v. Dost, a federal judge suggested a six-step method of evaluating images to determine whether the nude image of a child could be considered legal or illegal. The criteria were as follows:

▪ If the focal point was the child's genitalia or pubic area

▪ If the setting of the visual depiction was sexually suggestive

▪ If the child was in inappropriate attire or an unnatural pose

▪ If the child was fully, partially, or completely nude

▪ If the visual depiction suggested coyness or a willingness to engage in sexual activity

▪ If the visual depiction was intended or designed to elicit a sexual response from the person viewing it

Although the list of factors isn't comprehensive, and other aspects of an image may be relevant, the Dost factors do provide a good measurement for determining whether an image is illegal. They address the fact that just because nudity is present, labeling it child pornography may not be applicable.

Child Modeling Sites

As with most child modeling sites, children appear with permission of the parent or legal guardian, because the child is too young to consent. The rationale for parents allowing the photographs has ranged from raising money for college (as in the case of the now defunct Lil' Amber site that featured a 9-year-old girl) to gaining exposure for legitimate modeling jobs—neither being a particularly good reason for creating sexualized images of a child. In 2002, Representative Mark Foley took on combating this type of exploitation and introduced a bill called the Child Modeling Exploitation Prevention Act, which would ban selling photographs of minors. Needless to say, doing so would impact legitimate modeling companies and other businesses, and due to opposition the bill never left committee. As for Rep. Mark Foley, he resigned in 2006 after ABC News reported on his inappropriate e-mails and sexually explicit instant messages (IMs) to teenaged pages.

Child Pornography without the Child

Laws against child pornography are based on the assumption that children are harmed in the making of the pictures. The pornography laws generally apply to visual depictions only, with the written word (stories about child sex) being protected by the First Amendment in the United States. However, even though no child is harmed in the generation of certain types of pornography, it is viewed by those who abuse children sexually or by those who are intrigued by the idea of having sex with a child. Many different types of child pornography don't involve actual children.

Virtual child pornography is a type of digital fakery in which the images appear to be of children having sex or posing nude, but they are actually digitally manipulated or morphed images. Such images can be created via simple cut and paste or via extensive digital editing. Superimposing a child's face onto a body of a minor, or showing someone with a body type similar to that of an underage child, gives the illusion that a child is actually posing nude or having sex.

Virtual Pornography Being Virtually Legal

In the United Kingdom, under the Protection of Children Act (1978) and Section 160 of the Criminal Justice Act of 1988, it is a criminal offense for a person to possess either a photograph or a “pseudophotograph” of a child that is considered indecent. The term pseudophotograph is defined as an image made by computer graphics or that otherwise appears to be a photograph. Typically, this is a photograph that is created using a graphics manipulation software program such as Adobe Photoshop to superimpose a child's head onto a different body.

The issue of “virtual child pornography” that uses high-quality, computer-generated images instead of real photographs is a matter of intense debate. It is illegal in some countries, such as Germany, where it is punishable by up to five years' imprisonment, but it is legal in other countries, such as the United States. In April 2002, the Supreme Court struck down the federal laws making this form of kiddie porn illegal. At the time of this writing, the Justice Department and members of Congress were intent on rewriting those laws more narrowly, in a way that would outlaw virtual child pornography which is indistinguishable from the real thing while still allowing the law to pass constitutional muster.

The Motives of Those Who View Child Pornography

People view child pornography with different intentions or purposes. Although some women do access or produce child pornography, most of those who create, access, and disseminate this type of material are men. Those who are sexually attracted to this type of pornography will often fall into one of these categories:

▪ Passive pedophiles, who use the Internet to access and download kiddie porn and use photos and stories of children engaging in sex (usually with adults) to feed their own fantasies. Even if they never act out those fantasies in real life, in the United States and many other countries, it is illegal to even possess child pornography in photographic form.

▪ Active pedophiles, who use the Internet to find their victims. These criminals usually also collect child pornography, but they don't stop at fantasies. They often hang out in chat rooms that are frequented by children and engage them in virtual conversations, attempting to gain their trust and lure them into an in-person meeting. They might then rape the children, or they could simply “court” them, preferring to gradually seduce them into sexual relationships. Because children under a certain age (which varies from one state to another) are not considered capable of consenting to sex, sexual conduct with a minor is still a crime, even if the child agrees to it. Usually the offense is defined as statutory rape or some category of sexual assault.

▪ Sexually curious, in which the person is accessing the images out of curiosity. For example, people under the age of 18 may access child pornography to view people within their own age range, whereas adults may visit a site because they are curious as to what kiddie porn is.

In some cases, people have viewed a considerable amount of pornography, and then they move on to forms of pornography by which they would have initially been offended. In other words, they have viewed so much porn that they have become desensitized to it. Such people will visit sites and possibly download images with little regard to its implications, because to them, porn is porn. When analyzing a computer, it is easy to identify such people because the computer contains a diverse range of different types of pornography. For example, images may include erotic images from men's magazines, amateur adult porn, images of older women or men (possibly even senior citizens) posing or engaged in sex, as well as a number of other genres. Regardless of whether the computer contains a prevalent amount of child pornography, it is important to remember that even a single image of child pornography can result in criminal charges.

The Victims of Child Pornography

According to the National Centre for Missing & Exploited Children's report mentioned previously, of those arrested for possession of child pornography:

▪ Eighty-three percent had images involving children between the ages of six and 12

▪ Thirty-nine percent had images involving children between the ages of three and five

▪ Nineteen percent had images of infants and toddlers under the age of three

As previously mentioned, most of the children used in child pornography are female victims, and although these figures do not account for adolescents, you can see that most of the children involved in child pornography are between the ages of six and 12. Although the gender is agreed upon by most studies, an article available from the Computer Crime Research Center (www.crime-research.org/ articles/536/) states that “Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) personnel estimate that over 50% of all child pornography seized in the United States depicts boys rather than girls. Canadian Customs puts that figure at 75% for Canada.” Regardless of gender, the children may be required to pose nude for softcore images, or they may be used for hardcore pictures and videos in which they perform various sex acts.

How they become victims of this crime varies, but sufficient information shows that it is an international problem. Children may be exploited in countries with low ages of consent, where there are no child pornography laws, or where existing laws aren't enforced. Poverty is also an issue, as children who are impoverished and/or living on the street are often targeted for prostitution or pornography.

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, countries with low ages of consent for exploitive activities such as prostitution, or where underage prostitution is not enforced, can be destinations for child sex tourism and child pornography. In a report from Save the Children, titled “Position paper on child pornography and Internet-related sexual exploitation of Children” (www.inhope.org/doc/stc-pp-cp.pdf), it was reported that up to 50 percent of child prostitutes were also subjects of child pornography. As such, child prostitution provides an avenue for pedophiles and pornographers to acquire children to abuse.

The areas of the world where the production of child pornography is most prevalent have changed over the years, ranging from Japan, Taiwan, Russia, and other countries. According to a 2004 report by the Russian National Consultation on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children (www.ecpat.net/eng/Russia.asp), child pornography makes up 25 percent of the pornography on Internet Web sites, and more than 50 percent of these contain child pornography from Russia. It is estimated that pornography from this country involves tens of thousands of children being exploited.

Child pornography created in Russia, the Ukraine, and other areas of the former Eastern Europe has also become a problem over the past number of years. Although not limited to these parts of the world, young women or girls may be offered modeling jobs that are actually child pornography. They may be required to pose nude or while engaged in sex acts. The images are then sold over the Internet or through various magazines in countries where the legal age is low enough to make publishing legal.

In some cases, the level at which children are procured is highly organized and insidious. In Russia, businesses involved in child pornography will pose as modeling and fitness schools, where children are actually groomed for participation in pornographic films. One such institution was the “Aphrodite School” that operated as a school for young models. It had an enrollment procedure that should have seemed odd to parents, whereby the girls had to show themselves naked before they were accepted. Although this may seem inconceivable to most people, in many cases the parents involved were living in destitution with no chance for a better life. Poverty mixed with opportunity can create an atmosphere in which children appear in pornography with their parents' permission or endorsement.

Regardless of the situation, a child is powerless and cannot give consent to appearing in pornography, and thereby doesn't have a choice. As stated in the Save the Children report mentioned previously, “German police estimate that 130.000 children in 1993 were forced by parents or other acquaintances to participate in the production of pornography.” Beyond commercial pornographers and child sex tourists, children may become victims of the very people they believe are there to protect them.

The Role of the Internet in Promoting Child Pornography

When the Internet began to become popular in the mid-1990s, child pornography began to appear on various sites. In these early years, most of the pornography came in the form of photographs or pictures from magazines that were converted into an electronic format using scanners. These were often photographs of children taken by child abusers, or magazines from the Netherlands featuring adolescent girls. Another common source was nudist magazines, showing naked minors playing sports or other activities. In some cases, these scanned images were more than a decade old, but the amateur production of child porn soon increased with newer photos. Once digital cameras become more affordable, higher-quality images began to appear more frequently on Web sites located in countries where child pornography laws were nonexistent or not enforced.

The Internet has created a new marketplace that makes the distribution of child pornography easier. According to the Save the Children report cited earlier, “Child pornography on the Internet has expanded dramatically in recent years and appears to have largely overtaken and absorbed previous production and distribution methods of child pornographic material.” As with any other kind of pornography, anything a pedophile wants is just a mouse-click away.

By being part of the global village, pedophiles have been able to establish international child pornography rings. The Internet can be used to make connections with others who possess child pornography, allowing them to trade and sell it with one another as well as learn the dos and don'ts to avoid getting caught. Not only is the Internet a resource for porn, but it is also an educational tool.

Driven from Back Alleys to the Information Superhighway

The Internet provided a relative safe haven for those who sought child pornography. Prior to the Internet, the availability of child porn was often limited to behind-the-counter purchases at adult bookstores or to ordering magazines and films from other countries and receiving them through the mail. In the 1970s, adult bookstores began to sell child porn openly, which incited new laws and police crackdowns, making the availability of these items more difficult to purchase. This lasted until the 1980s, when computers provided a new method of exchanging data. Bulletin board systems (BBSes) are programs that can be installed on a computer, allowing other computers to dial in and access e-mail, exchange messages, download files, and perform other functions that became commonplace on the Internet. During the 1980s, those who sought child pornography no longer had to travel to unsafe neighborhoods; they could now download child porn to a computer.

Because BBSes were privately run, what was allowed on the board depended on the person who owned the computer on which the BBS was installed. Individuals could start their own BBSes, and create private areas that limited access to anything they wanted, ranging from illegal software to child pornography. However, although BBSes did exist that provided access to folders filled with child pornography, many of those who ran these boards discouraged such activities and commonly banned people from their BBS. Another reason they were self-policed was that most of those in law enforcement were computer-illiterate—remember that computers were relatively new at this time. By the time the police took a serious interest in BBSes, many of them were shutting down from lack of use, because most people had discovered the Internet.

Whereas BBSes provided access to a local community of computer users, the Internet provided availability to international sources. In terms of child pornography, it opened up the market. It allowed pedophiles from around the world the chance to communicate with one another and share pictures and videos, with a greater degree of anonymity than they'd ever had before.

The ability to download more pornography and save it to a computer also stemmed from advances in connectivity and storage media. The sizes of hard disks on computers increased and their prices dropped during the early 1990s, allowing them to acquire more files in less time. A 500 KB file would have taken more than 35 minutes to download from a BBS using a 2400-baud modem, but when the Internet became popular, ISPs required people to have a modem that could connect at 28.8- or 33.6 Kbps. This same 500 KB file now took less than three minutes to download. Today, people commonly have high-speed connections to the Internet, meaning that it now takes a few seconds to download this same file. The advances in speed and storage made it possible for higher-quality images and full videos to be distributed over the Internet.

As we'll see in the next section, the Internet provided a number of features and areas where child porn could easily be obtained. In many cases, the pornography could be acquired at no additional cost, making it significantly cheaper than previous methods. Consider that in the 1970s, kiddie porn would have to be ordered through the mail. The postal service was the main distribution source for child pornography at that time. Whenever child porn was identified, the package would be delivered to the intended recipient, meaning that he or she would have to sign for it. Postal inspectors and police would execute a search warrant and arrest the person who signed. Using information associated with the order, the evidence in a single case could include the order form, the check or money order to pay for the porn, the signature provided by the person who accepted the order, and the porn itself. The paper trail was easy to follow, making the risks associated with manufacturing and possessing child pornography extreme. The risks were less so with the Internet, and because the costs of those risks weren't passed on to the consumer, it was cheap to pay for the porn when required to do so.

Tools of the Trade

A number of tools and services are used to acquire child pornography. Basically, any Internet tool that has the capability of sending and receiving a file can be used to exchange images, videos, and other files containing pornographic images. If these tools also have the capability of communicating with other people, online predators may use them to meet children online.

Because e-mail allows you to attach files to a message, any images, videos, audio, or other files can be sent with a message. E-mail is used to distribute child pornography in small quantities, attaching one or a few files to any message. A person may send child pornography to others who have an interest, or a pedophile may send messages to a child with these images attached to seduce or groom the child into having sex or sending back pictures of him- or herself. Because a message can be associated with the image, the predator can tell the child that this is what he'd like to do, and possibly pique the child's interest or desensitize him or her and loosen any inhibitions.

Mailing Lists

Mailing lists are lists of e-mail addresses that are subscribed to, allowing you to join a group that shares a common interest or a need to exchange information. When you send an e-mail to the group's e-mail address, everyone in the group receives it. Numerous mailing lists are available on the Internet, and you can subscribe to them by sending an e-mail to either an automated program or a moderator. The moderator's purpose is to ensure that any rules pertaining to the group are observed, and to facilitate adding new members to the list. Because mailing lists may consist of any type of group with a shared interest, it follows suit that there are those available for sharing child pornography, or information on how to obtain it (for example, lists of sites, and so on).

E-Groups

An e-group is a service that allows users to send e-mails to members, post messages, share pictures, and chat with other members, among other things. One popular site for e-groups is Yahoo! Groups (http://groups.yahoo.com). By searching such sites, you can find groups dealing with everything you can imagine, and a number of things you can't. Once you find a site, you subscribe to it much like a message list. Certain people can even have different access from others, controlling whether certain trusted users have access to specific photos or other items that the rest of the group can't see.

Newsgroups

Newsgroups or discussion groups are used to exchange messages and files through Usenet, which was established in 1980 and continues as one of the oldest computer networks. These groups allow people to post publicly accessible messages, which are distributed across news servers on the Internet. Each group may contain thousands of messages from people, and there are tens of thousands of newsgroups that you can view or subscribe to. You access newsgroups using a newsreader or features in e-mail programs such as Outlook Express, which connect to the news server to download groups and their messages.

There are newsgroups that address specific interests and topics, which may or may not be monitored by a moderator. By accessing a group, you can post text or binary files, including images, videos, audio, software, and other files. This makes newsgroups one of the largest possible sources of pornography on the Internet, with specific groups geared toward child porn. As shown in Figure 9.8, some newsreaders allow you to filter the listing of groups (which in this case exceeded 60,000) so that you can find ones with specific subject matter. The names of these groups reflect their content, with some of them providing free downloads of pornographic images and videos featuring adolescents and prepubescent children.

|

| Figure 9.8 A Listing of Available Newsgroups Using the Forte Agent Newsreader |

Peer-to-Peer Applications

Peer-to-peer (P2P) applications are used to network different computers together over the Internet so that people can share files on one another's hard drives. Examples of P2P networks include Kazaa, Morpheus, FreeNet, and Gnutella. Users access the distributed network of computers using P2P software, which allows them to share files and have a shared directory on their hard drive searched. These tools can be used to search the computers making up the network for specific types of files or files that match a certain criterion.

When you've heard of file sharing, you've probably heard it in the context of people sharing copies of music files with one another. However, more than simply music is available on these networks. Using them, you can download literature, programs, videos, images, and other items. However, although the music industry has made an issue of file sharing, a more important issue of P2P is that it is also used to exchange child pornography. In fact, according to the Internet Pornography Statistics Web page at Top Ten Reviews (http://internet-filter-review.toptenreviews.com/internet-pornography-statistics.html), in 2006 there were 116,000 Gnutella requests daily for child pornography.

Web Sites

Web sites are a popular method of providing access to child pornography. Web sites are collections of files called Web pages, which are documents written in HTML that may contain scripts, Java applets, or other programmed features which make the site automated or interactive. These pages may consist of text, pictures, audio, video, or other content that Internet users can access using Web browsers such as Internet Explorer, Opera, Safari, and Firefox. These browsers access the site and their pages using a unique address, called a Uniform Resource Locator (URL). As mentioned, many of the sites providing access to child pornography may also charge a fee. The owners of these sites may create their own porn to sell online, or collect it from other sources on the Internet.

A new twist to being able to find such sites is the image search features in search engines. Search engines are used to find specific sites via keywords or phrases that you enter. Sites such as Google also have features to look for images that are on sites, allowing you to find sites that have specific names or content. For example, by going to http://images.google.ca, you could type in “child porn” and preview images from sites around the world. By clicking on one of these images, you are then taken to the site. Not only is this useful to pedophiles interested in child pornography, but it can also be a useful tool for investigators trying to find these sites.

Chat Rooms and Instant Messaging

Chat rooms are Web sites or programs that allow people to send text messages to one another in real time. The chat room works as a virtual room, where groups of people send messages that others can read instantaneously. Often, people in chat rooms will use aliases or nicknames to provide some anonymity, and will use the chat room to meet others. If individual visitors to the chat room wish to talk privately, they can enter a private chat room, which allows two or more people to send messages privately to one another. Some examples of chat rooms are Internet Relay Chat (IRC) and Web sites such as Talk City (www.talkcity.com).

Among other groups, chat rooms appeal to adolescents and teenagers, who communicate with others and use features to send files to one another online. Because of this, online predators will use chat rooms to meet young people and attempt to engage in sex chat, where individuals in a private chat room will tell one another what they like to do sexually to one another. Basically, sex chat is the textual equivalent of a dirty phone call. In addition to this, features in chat programs allow people to send pictures to one another, enabling pedophiles to exchange child pornography, or groom potential victims with pictures.

Instant messaging is similar to the function of a private chat room. It is a service that allows two or more clients to send messages to one another in real time using IM software. Generally, each IM client ties into a service that transfers messages between other users with the same client software. However, there are programs such as Trillian that allow users to consolidate their accounts on different IM networks and connect to AIM, Yahoo! Messenger, Windows Live Messenger, ICQ (I Seek You), and IRC all within a single interface. In recent years, such features have also been folded into other IM software, such as Windows Live Messenger supporting messages exchanged with Yahoo! Messenger clients.

Because so many young people enjoy chat rooms and instant messaging, these features are also being incorporated into other tools. For example, a game used on an Xbox or PlayStation may provide features so that you can chat with people you're playing against online. Although this can be fun for those with a real interest in the game, it can also be used by pedophiles to connect with children and adolescents who are trying to connect with young people in new ways.

Challenges in Controlling Child Pornography

Cybercrime cases often have more challenges than other, more traditional types of crime. To effectively combat computer-related crimes, those directly involved in investigating these crimes need specialized training and equipment, which (as with anything dealing with computers) needs to be upgraded every few years, at least. This can be difficult for many police organizations, as the costs for implementing specialized units can be quite high. This can limit the ability to investigate computer crimes at its most basic level.

In many cases, a crime might originate in one country where legislation differs from that of your own country or where the act is not a crime at all. For example, although child pornography might be defined as pornographic images of persons younger than 18 years of age in North America, the legal age to pose for such images in other countries might be considerably younger. This difference can cause a dilemma for law enforcement officers, because it is legal for a Web site in one country to distribute the images but illegal for people in other countries to download them. Investigators can arrest people in possession of the pornographic files, but they might be powerless to shut down the Web site distributing the pornography.

In Cyprus, police face the obstacle of conflicting laws. As did most European countries, the Cypriot government signed the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime in 2001, and agreed to take action against such crimes as child pornography. However, existing laws protect privacy, and state that communication services are prohibited from disclosing personal information. Under Chapter 17 of the Cyprus Constitution, a person's right to privacy can't be infringed by listening in on private telephone conversations, which means that any data transmitted over the phone line (such as child pornography) also can't be used as evidence. Unless the material is found on the hard disk of a computer or other media, Cypriot authorities can't investigate incidents in which a person is downloading or distributing child porn.

Not all countries view a child in the same way, such as Norway which considers the sexual maturity of a child. Norway considers that child pornography is sexually explicit material with a child under the age of 16, but if the child's sexual maturity is obviously over, under paragraph 204 of the Penal Code he or she isn't considered a minor in terms of child pornography. Whether a child has reached a certain level of sexual maturity is determined on a case-by-case basis by the court. However, this doesn't mean that a person can't be punished in such situations, as charges against someone producing child pornography could still be filed under other laws dealing with assault or exploitation.

The ability to perform investigations that go outside jurisdictional boundaries almost always relies on cooperation with law enforcement entities in those areas. Police in one country generally have no official jurisdiction in other countries. However, when police in different countries work together their impact on crime can be significant. This impact is seen in a number of collaborative efforts between police and other law enforcement agencies in various countries.

As nations cooperate with one another in various endeavors, a global vision of what is considered right and wrong has been established on a variety of subjects. Because numerous countries don't have laws or adequate legislation dealing with child pornography, cyberterrorism, and other activities related to cybercrime, international consortiums saw a need to provide a legal framework for updating the laws of these countries. International organizations and political coalitions have influenced legal changes in many countries, pressuring some countries to create new laws or revise existing ones to deal with crimes that the majority of the world considers abhorrent or potentially devastating.

Anti-Child Pornography Initiatives and Organizations

Because a simple cybercrime case can quickly expand to involve law enforcement in other areas, there is a need for initiatives and organizations to aid in coordinating and assisting in these investigations. In the sections that follow, we'll look at a few of these initiatives and organizations, including:

▪ Innocent Images National Initiative

▪ Internet Crimes Against Children

▪ Project Safe Childhood

▪ Child Exploitation Tracking System

Innocent Images National Initiative

The FBI developed the Innocent Images National Initiative (IINI) as part of its Cyber Crimes Program for the purpose of identifying, investigating, and prosecuting those who use computers for child sexual exploitation and child pornography. In performing these tasks, the FBI also attempts to identify and rescue children being exploited or appearing in these images.

Originally, the IINI provided one of the few online presences of law enforcement, although this is no longer the case due to the volume of police and other agencies that pose undercover in chat rooms and other forums, attempt to identify online predators, or are involved in cybercrime investigations. Because of the involvement of local, state, and international law enforcement officials in these endeavors, the IINI provides training and assistance, as well as coordinating national or international investigations.

Over the years, the IINI has expanded its mission to include sexual tourism, in which American citizens or residents travel for the purpose of having sex with minors. Several federal statutes in the United States deal with sex tourism and trafficking (18 U.S.C. §§ 1591, 2421, 2422, and 2423), and make interstate and international sex tourism and sex trafficking within a state illegal. Although its focus now includes these types of illegal activities, this hasn't deterred the IINI from attempting to identify, investigate, and prosecute those who produce, distribute, or possess child pornography.

Additional information on the IINI is available on the FBI's Web site at www.fbi.gov/publications/innocent.htm. By visiting this Web page, you can view the latest statistics on the IINI, and also view information on individuals the IINI has added to the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives.

Internet Crimes Against Children

The Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) Program is a network of 46 regional task forces that are funded by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). It was created to provide federal assistance to state and local law enforcement so that they could better investigate computer and Internet-based crimes that sexually exploit children.

The program is funded through the United States Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and provides a variety of different resources that are useful to organizations and law enforcement officials dealing with crimes against children, including the following:

▪ The Training & Technical Assistance program provided by ICAC (www.icactraining.org) offers information and resources for training ICAC initiatives, as well as contact information for technical support. This trains law enforcement officials on how to perform undercover chats, investigative techniques, and a variety of other topics and technologies. It also provides presentation material to teach students ranging from kindergarten to high school, parents, and other interested parties.

▪ The ICAC Research Center (www.unh.edu/ccrc/) provides up-to-date statistics, publications, and other resources on sexual abuse, exploitation, and other crimes and issues dealing with children.

▪ The e-mail distribution list provided by ICAC allows individuals affiliated with ICAC to communicate with one another and share information.

Project Safe Childhood