Phase 3—Combining the Customer Value with That Expressed in the Offer

The Objectives of This Step

• To move beyond ring 4 of the circle of trust

• To place customers at the center of the negotiation experience, permitting them to be receptive to your arguments

• To present the offer system as ethical and effective as possible and to argue your differential value

• To fuse your idea of value and that expressed by your offer with that of the customer

• To present the price linked to the overall value of the offer

Renato finally has a clear idea of the customer’s needs and he must now present his offer. The company is pushing hard to sell the sports models, so our seller feels “obliged” to steer the deal this way, regardless of the customer’s requirements. Renato hopes the person in front of him will not be the insecure and uncertain type who looks bewildered when you confidently reel off the technical data to show you know your stuff. Worse still, the customer may just interrupt by immediately asking, “How much is it?” forcing you to face the uncomfortable topic of price. Renato’s proposed car has a considerably higher price than that of some competitors, but he is ready to rip his rivals’ offer to pieces and if he must, he’ll cut his price! How can Renato find a point of contact between his objectives and those of the customer so that everyone is satisfied with the negotiation? We will see how Sales Ethics can help … .

Each time a customer meets a salesperson they ask themselves, more or less consciously, “Why should I buy from you?” Phase 3 of Sales Ethics aims to find a convincing answer to this question.

When meeting a potential customer, we are dealing with a human being who shares the following characteristics:

• One or more needs, or specific requirements, which have not yet been satisfied and the desire to achieve a specific objective related to them; and

• One or more motivations for purchase that drive and guide his decisions.

When we talked about customer value in Chapter 1, we were defining the result of the fulfillment of these needs in line with the motivations that drive them. The investigation phase served to reveal these two important elements. Now is the time to use them to guide the way you present your product, by arguing and setting out your offer system so that it maximizes the customer value. We remind you that you are part of this offer system, so your role is to not only present it in the best way possible, but also actively contribute to its creation by adapting your behavior and relationship style to ensure the customer can satisfy those needs thanks to a rewarding human exchange. A customer’s perception of esteem, gratification, pleasure, and confidence will depend more on you, than on your products or services!

Satisfying Needs and Motivations for Purchase

To set up an effective and ethical negotiation, it is necessary to remember that each customer buys depending on his or her own reasons, not on the basis of yours! You have probably come across at least one salesperson yourself who was a very smooth talker but failed to interest you in any way. It is highly likely that this person was presenting a potentially interesting offer that would have suited your needs, but they forgot to tune in to your needs and instead described what they themselves would have liked.

If you want to help your potential buyers, you must accurately identify their needs and motivations, and utilize this knowledge to adapt your presentation of the product or service to that specific person.

When customers are ready to satisfy a need, they have three options: they can decide to buy from you, from another seller, or not to purchase anything from either (at least for the moment). When you have recognized their needs, your responsibility lies in helping the customer to satisfy them.

A few paragraphs earlier, in Phase 2, we illustrated the investigation of needs and motivations by comparing it to an iceberg. We want to emphasize once again that we can only identify the motivations underlying the needs and hence what drives a customer to desire a particular purchase, through a skillful use of questions and active listening.

We would add something to the definition given earlier, by distinguishing two main categories of motivations:

• Escaping from pain: These are motivations that drive people who tell us what they want to avoid, the situation from which they wish to escape or what scares them: “our staff turnover is too high,” “I want to avoid a downtime of production,” “I’m tired of being unfit.” To help customers who feel themselves in difficulty, you should underline the time wasted if they fail to resolve the issue. You will have to highlight the negative aspects of their failure to tackle the problem: “A high staff turnover does actually cause you to lose information and waste a lot of time and resources training new staff.” “Certainly, downtime involves considerable costs for a company because it blocks production and slows deliveries.” “Being unfit also leads to health risks.”20

• Toward pleasure: You can recognize that these are the motivations when customers tell you what they want, what positive outcome they expect, and what is their desired solution: “I would like loyal employees who remain in my business for a long time,” “I want continuous production,” “I want to get fit.” These people need to know how much better they will feel when they have fulfilled their desire or resolved their need. They want to be guided to make their purchase by someone who knows how to highlight the benefits they will get: “You’ll finally have employees who stay with you,” “Repairs and maintenance are quick so you can be sure your production line remains active,” “You’ll soon notice the difference with this fitness training program.”

The motive why the customer wishes or needs to buy your service or product can be divided into 10 categories that can be triggered by either of the two forces that propel us to act as explained above. The following list illustrates these categories when the driving force is toward pleasure, but they could be just as easily be illustrated as away from pain:

1. Usefulness and convenience (ease of use, simplicity, desire for comfort)

2. Saving or earning of money (bargain, special offer, cost-effectiveness)

3. Speed (use, response, delivery, procurement)

4. Safety (reliability, tranquility)

5. Health (wellness and fitness)

6. Innovation (being up-to-date, get the latest buzz)

7. Status and prestige conferred by the purchase (exclusive, pride, recognition, visibility)

8. Esteem (belonging to a group, to be accepted and respected, praise)

9. Sociability and friendship (affection, bonding with the seller, special relationship)

10. Personal growth (increase in knowledge, self-fulfillment, development of performance, or personal standing)

Your conversation with customers will enlighten you regarding their needs and motivations for a purchase. Bearing in mind the list of questions that we gave at the end of the section on “Practical Tips for Asking Ethical and Effective Questions” let us once again imagine a conversation between Renato and his hypothetical customer:

Customer: “I want to buy a new car.” (need )

Renato: “How many miles do you drive a year?” “Where do you generally use your car, on the highway or in town?” (investigating need )

Customer: “I do about 30,000 miles a year, mainly on the highway.” (specifying need )

Renato: “What’s the most important thing you look for in a car?” (researching motivation)

Customer: “The main thing is to be comfortable when I’m driving so I don’t arrive with backache.”(motivation)

In this short dialogue, the motivation expressed by the customer indicated the desire of escaping from pain (in this case specifically back pain). Renato would now be equipped to describe the best automobile for this customer in a manner suited to the customer’s values and understanding. For example, he could say, “I understand how annoying it can be to arrive at your destination with bad back pain that stops you from concentrating on your work, so my proposal for you is a model equipped with ergo-nomic seats and smart suspension.”

An effective way of moving from the investigation phase (Phase 2) to the presentation of your proposal is to summarize the needs expressed by the customer: “As I understand it, you need a car that ensures comfort so you can avoid that annoying back pain, is that correct?” When customers give us explicit confirmation of their motivation or need, they also focus on the situation and fully realize what they are really looking for.

Exercise

• Do you know how to help customers to choose by using their purchase motivations? Think of a product or service that you sell and choose one of the 10 motivations listed earlier. Imagine that a customer expressed this motivation during the analysis stage in the form of escaping from pain and prepare a proposal line for your product that uses that particular purchase motivation as a lever. Now do the same for a customer wishing to move toward pleasure. Repeat the exercise with each of the 10 categories of motivations.

Adopt Your customer’s Point of View: Benefits and Features

We are now at the long awaited stage that all our preparation has so far be leading up to: proposing your offer.

The customer has been waiting for this moment too, to see if you can resolve the need that brought them here.

This is the moment that defines an ethical salesperson. The salesperson will once again remember that the customer is the protagonist in the relationship experience that they are sharing and will talk about the aspects that will be of interest and significance for that customer.

All products and services have a series of specific features or technical qualities and distinctive characteristics that can be demonstrated “this shirt is 100 percent cotton,” “this car is equipped with ABS,” “this website is in HTML5,” “our company has been on the market for 30 years,” and so on.

Imagine, if you will, the classic scene where the proud seller spouts on about himself or herself and the company he or she works for as well as the product or service being sold by providing an endless list of features that have been diligently memorized. Now imagine how the customer, who may be initially interested, will progressively sink deeper into boredom as they watch a show starring the seller alone. A number of questions are now forming themselves in the customer’s mind: “Why should that interest me?” “Why are you telling me all this?” “How is that going to make my life better?”

It is actually easy to stop customers becoming bored, you just have to present your offer system by highlighting what benefits they will derive from any specific feature, and underline how they will resolve their needs or fulfill their desires thanks to you. When you talk about the benefits, you must state what your offer does and what it will do for them. This is infinitely more interesting than describing what the product is and who you are.

“This shirt is 100 percent cotton and ideally suited to your sensitive skin.” “This automobile is equipped with ABS so if you have to brake suddenly on a wet surface it will hold the road better.” “I’ve been working in this sector for 10 years so I can give you sound advice based on my experience.”

If the market in which you operate is business-to-business you will need to highlight two distinct levels of benefits:

• Those aimed at your customer: For example, if you work for a company that manufactures furnaces and you introduce yourself to a local dealer to convince him to distribute your products, you can highlight the speed and reliability of delivery that will ensure his service to his customers is punctual and that there is no risk of losing sales opportunities because the goods are unavailable

• Those aimed at your customer’s customer: Provide him with arguments to promote his sales. If the dealer’s potential customers are plumbers and house owners, then highlight advantages such as ease of installation, warranty services, and any other arguments that may be of use when he is dealing with his customers.

In this central and crucial stage of the negotiation, we cannot overestimate the importance of coupling both the technical competence and human skills that all Ethical Salespeople must possess.

Competence is essential to put together the best deal; you must have a thorough knowledge of the specific characteristics of your offer and the benefits associated with them so that you know which features to emphasize each time.

Yet if a seller who has a broad technical knowledge is unable to create a rapport, he will tend to end up showing off the breadth of his knowledge, perhaps with a thorough description of the product or service he is so passionate about, while forgetting the object of the exercise.

Also, if a salesperson who is attentive to human relations and can create empathy in customers lacks technical competence, he will be not credible and risks losing the customer’s trust.

How do you avoid the temptation to make it all about you as you gush on about the object of your sale in technical jargon? Here are some practical tips:

• Explain the benefits: Many of the sellers we meet start out by assuming that their customers will know in advance the benefits of their product and its features, and that it is superfluous to specifically state them. Not so! In fact, customers may know very little (indeed, they come to us because we are the experts!) and they certainly cannot read our minds. If you want to be sure that your customers know something (and you will most definitely want this because it’s the lever to inspire their interest and involvement) you must be the one to tell them! “This drying rack is made of aluminum (feature) so it is very light and easy to move (benefit).” If you want to be more succinct, omit the feature and highlight the benefit directly, “This drying rack is very light and easy to move.” You should never tell them, however, the characteristic alone, “This drying rack is made of aluminum,” because this will leave the customer puzzled, “So what?”

• Focus on the other person: Customers need to feel that they are at the center of the deal. They want to know that we are there to help them solve their needs and respond to their wishes. Our behavior will prove to potential buyers that we are willing to look after them, to listen carefully in order to understand their priorities, and satisfy them. Sometimes the details that we consider unimportant may be very important for other people. Your objective is to see your products through the customer’s eyes, and blend your idea of value (and that expressed by the entire offer system) with theirs. For example, if you wish to highlight your professionalism and your technical knowledge, you should remember that this might respond to the customer’s need to have a knowledgeable and professional partner. In this case, both of you are wanting to maximize this particular aspect of the offer because it is associated with your shared idea of value. However, you must draw attention to this in a way that is compatible with the customers’ point of view; otherwise, you may bore or even scare them away. Enable them to appreciate how your knowledge and professionalism can benefit them by, maybe, saying, “You can count on my many years of experience to help you make the right choice—ask me everything you need to know.”

• Tailor your presentation: Different customers buy the same items for completely different reasons. For example, you and I may both have chosen the same car, but while I bought it because it is comfortable and has a spacious trunk, you wanted it for its powerful engine. Another person may have made the same choice on the advice of a friend, another again because of the prestige of the brand, and so on. We cannot script, therefore, the perfect sales line—there is no one-size-fits-all, rather each presentation must be as special and unique as the person with whom we are dealing. Since we do not know whom we may meet and what their differences may be, it is crucial to prepare beforehand so you can connect each feature with as many benefits as possible and be ready to use them on the basis of what emerges from your conversation with each customer. Let us take as an example of a restaurant that uses all homegrown organic ingredients and list some of the benefits for the end user: safety of eating fresh foods, genuineness of organic crops, intense flavor of freshly picked ingredients, enhancement of the territory, reduced pollution from pesticides, customized dishes due to direct sourcing, and so on. Overall, to effectively tailor your presentations, you will need to have a detailed knowledge of what you are selling and the values of your offer system (expertise) and of the customers and their idea of value (ability to relate to others), so that you can match the various characteristics of your offer with the needs expressed by your customer.

• Sell to your customers and not to yourself: Many sellers persist (despite their failures) in presenting the product as they would like it, by highlighting what they would choose as benefits, based on their own motivations for buying. They will only manage to make a sale if they have the good fortune to meet someone just like themselves! It requires considerable flexibility to consider our offer through our customers’ eyes and identify with them, thus building an empathetic relationship. As we have repeatedly stressed, customers each have their own concept of value (and their objective is to maximize this value through our exchange) and it will differ from that of the seller. Your professional duty is to find the methods and language that will permit your different worlds to come to a mutual understanding.

• Be useful to the customer: Customers do not buy things but solutions to their needs. More than the technical details of your products, they are interested in learning how your solution will be useful and enhance their work and their life. When you explain the details and specific features of your offer, we suggest you always make it quite clear how they will directly affect the customer. A few years ago, in his book The Marketing Imagination, Harvard Business School’s legendary marketing scholar Theodore Levitt famously quoted a phrase from Leo McGinneva: “People don’t want quarter-inch bits. They want quarter-inch holes.”21 If you really want to be helpful when dealing with your prospect, you will have a wealth of suggestions, provide expert assistance and consultancy, and be careful to ensure that your nonverbal language reinforces trust during the exchange.

• Transmit confidence and reliability: If you explain in clear, neutral, and simple language the connection between the features of your offer system and the benefits for customers, they will pick up on your confidence and have greater confidence in you. For example, “Bearing in mind your needs, this policy has feature A which will provide you with benefit B.” If necessary, you can back up your proposal with technical features, demos, articles, and references as this will help to give substance to your presentation. When we build a relationship based on honesty and reliability, our customer relationship becomes a true partnership that will last through time.

• Choose the right number of words: If you start describing your offer before understanding precisely what your customers need, you risk making a proposal that fails to match their expectations and you risk saying too much, or too little, or highlighting aspects that are not of interest to them. Many of our colleagues are convinced that if you exaggerate the merits of a product you cannot go wrong, but it is not so. If you overdo the description of the features and performance of your offer, adding details that customers have not requested you will confuse them and create suspicion, or perhaps lead them to conclude that your product is too sophisticated. You must learn then to calibrate your descriptions, so you use neither one word less nor one more than is strictly necessary to inform your customers of the benefits and characteristics related to their real needs.

• Observe the reactions: While you are describing your product and stressing its benefits, tune in to your customers’ reactions without concentrating solely on their words. They may show interest in what you are saying with a smile or a nod, making a positive comment or picking up the product or drawing closer to it. Any of these signs indicate that you are on the right track, so keep it up! However, if you notice they are distracted (they look away, move away from the product, play with other objects) or maybe even annoyed by what you are saying (shaking their head, frowning, grunting, or nervously tapping a foot) change tack as smoothly as possible. You may have misconstrued their reasons for purchase and you need to probe further before continuing with your presentation. Take time to ask further questions to avoid getting deeper into trouble.

• Underline the uniqueness of your offer: As W. Brian Arthur taught us a few chapters ago, it is not always necessary to elbow rivals out of the market to close a deal. It may not be useful or it might indeed be counterproductive to compare your proposal continuously with the competition. Emphasize instead how unique your offer is. Remember that your long-term goal is not to wrest a slice of the market from the hands of your competitors, but to expand the pie so you will no longer feel besieged. Do not forget to transmit the intangible elements you are offering such as values, style of relationship, and yourself. These elements render your proposal unique and unrepeatable.

• Winning together: We have already said that customers, while listening to your presentations, ask themselves, “Why should this product interest me? Does it resolve my needs?” These are, however, not the only questions they ask themselves. A much more insidious question emerges just as you are about to present your solution to their needs, “Why did you choose this particular model for me? What do you gain from selling this one to me?” You have already obtained the customers’ interest (ring 4 of the circle of trust), but they are still far from fully trusting you! Of course, your use of concrete data and straight talking will convince them that you are not bluffing, but we urge you to go even further and tell your customers what you are aiming at! “I recommend this product because I hope you will be fully satisfied and come back to me next time” or “This service will allow you to see how we operate and how our we can benefit your business” are both statements that openly declare your goal. This will enable you, once and for all, to underline the idea that your customers’ benefit can be compatible with your own and highlight the fact that there need be no contrast between your idea of value and theirs. Complete, clear mutual satisfaction is the most valuable result to which you can aspire and will permit you to base your relationships on a solid foundation.

We will conclude this section by stressing that many of the suggestions we made here are equally valid when you are on the phone with a potential customer, and your aim is secure an appointment. Again, you must remember to put forward a proposal that highlights the benefits. The person listening is, in fact, wondering, “Why should I devote time to meet this vendor?” The more explicit you manage to be, by providing a clear reason, and concretely explaining what the other person has to gain, the closer you will be to achieving your goal. For instance, use phrases such as “I will be happy to find out more about your business from you so I may suggest the best way to collaborate,” “I will bring a prototype so you can appreciate first-hand the quality of our products.”

• Let’s prepare the arguments most suited to selling your particular products. Choose one of the products or services you offer and prepare a list, as comprehensive as possible, of its features and distinctive characteristics. Now match each feature with all the needs it meets, the benefits it brings, how it is useful, and the motivations for purchase with which it is linked. For example:

Service: training course in “sales techniques”

Features: 16-hour course divided into four weekly meetings of four hours each

Benefits (in brackets the motivations associated with this purchase):

1. It does not take away too much time from work each week (comfort, savings)

2. The contents are spread over time (gradual growth, ease of learning)

3. You can practice what you learn during the week (immediate use)

4. Office work does not fall behind (tranquility, serenity)

5. Regular meetings can strengthen relationships (socialization).

The Proper Use of the Price as Indicator of the Value of Your Offer System

Price is one of many features of the product system, neither the most important nor the only one, but a feature like any other. It will only play a leading role in your negotiations if, and only if, you have not sufficiently argued the rest of the elements that make up your offer. The reason many people give an exaggerated weight to the price is very simple: It is an easily comparable and measurable feature and thus clearly intelligible even for customers who are either inexperienced or unable, for whatever reason, to evaluate and appreciate all the other elements. The price will dominate when customers have information asymmetries and have no other way to determine the benefits of your proposal other than to assess it according to economic criteria.

Information asymmetries can be generated in two ways: your customers think they know everything about you and your offer or you have not managed to focus their attention on the entire product system. Actually, asymmetries of this kind depend on a combination of the two situations described earlier. In both cases, however, the seller can intervene to resolve the situation.

A key aspect regarding the price, and we cannot repeat this often enough, is that in the customer’s mind it is inextricably linked to the value.

Value and price are two sides of the same coin and if one is devalued, sooner or later the other will suffer the same fate. Never forget that the value of the offer system includes you and your professional expertise!

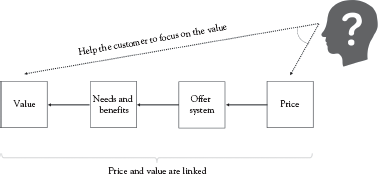

It is hence extremely important to support the price with a correct idea of value. As Figure 5.3 illustrates, to strengthen this connection you must guide the customer’s attention, initially focused only on price, along a path that permits you to argue all the features of your offer system. You will match each feature to real benefits, and thus to the concept of value that brought the customer to negotiate with you in the first place.

Knowing how to argue the price effectively is one of the fundamental aspects of Sales Ethics, because it helps to strengthen the relationship, overcome the conflict of interest, and satisfy your customers by instilling in them the certainty that they have made a successful purchase. In our personal and professional experience, we have often noticed how negotiations break down as soon as the price is stated, or more precisely, when the price is not properly stated.

Figure 5.3 Price–value diagram

In fact, many sellers do everything in their power to avoid stating the price, despite its importance. They happily present other information and emphasize all the characteristics of their product or service, but never say how much it will cost until the customers themselves—who have been thinking about this detail from the outset and have been vainly trying to get a glimpse of the price tag or price list—pluck up the courage to ask.

Beware: The seller must be the one to lead the negotiation and accompany his or her customers carefully and respectfully along the path that will enable them to find a solution to all their needs at the price agreed.

In Sales Ethics, the exchange between the dollar-product or dollar-service is transparent, fair, and satisfying for both parties; the customer and seller are not competing to gain divergent goals as suggested by the traditional economic theories.22

The ethical salesperson exchanges value with her customers, not just money in exchange for objects or professional services. There is much more at stake in commercial relations seen in this way, and the price will not detract from such an exchange.

Very often, in fact, it is the seller and not the customer who is anxious about the price! Salespeople frequently fear the reaction they will get when they name the price and are afraid of finding themselves with their back against the wall, forced to fight a humiliating and destructive battle. This negative approach may lead sellers to behave perhaps unconsciously in such a way that this is what actually occurs. With sweaty palms and trembling voice the salesperson whispers the price while staring blankly into the distance.

Informing the customers about the price should actually be a natural part of the negotiation and must be managed with ease. We provide below a number of practical tips to deal with this phase effectively.

• Give the information in a neutral way: In response to the simple question, “How much does it cost?” most of us will have at least once received a reply like “Eh, um, so, actually ... (sigh) this is rather expensive.” A seller who presents the price in this way should not be surprised if they then have to spend the rest of the time defending the value of their proposal! Give the precise price in a neutral way, speaking clearly, politely, and confidently. If you whisper, you give the impression that you are afraid of upsetting your customer. If you say, “It should be somewhere between $50 and $60” the customer will fix on the lower figure and it will be very difficult later to get anything higher. The price is a feature of your product or service; it is not a state secret or an embarrassing detail unless you are unconvinced of the value of what you are selling.23

• Choose the right moment to give the price: If the price is presented at the wrong time you may jeopardize the sale. If you start your presentation by stating the price, customers are unlikely to listen to the rest of your presentation, and not knowing what it refers to exactly, they will be unable to evaluate it correctly.24 On the other hand, if you leave the price until last, this will be the information that sticks in the customer’s mind. The ideal solution is to present the price embedded within your description of the offer’s benefits. If you find it useful, you can follow this model: present one or two features of your offer and the relative advantages, then give the price and then go on to present other benefits, along with a sample of the product or with an experience that leaves a positive impression in your customer’s mind. We saw this method applied successfully by a team of street acrobats performing near our house in Boston: In the middle of their show, when the audience’s emotional tension was at its peak, the leader of the group passed the hat round while exalting the commitment and courage needed to prepare such a demanding act. At that point, we all felt involved in what was happening and happily handed over some well-deserved dollars, secure in the knowledge that there was a real exchange of value. The artists traded their fearless expertise in exchange for our emotion and awe. The performance ended with a double somersault over four spectators squatting in the front row, amid riotous applause. If your approach to communicating the price is professional, customers will decide clearly and calmly to pay the money required in exchange for the value that you are able to create for them.

• Present alternative prices in the proper order: It is better to avoid the question “How much were you thinking of spending?” especially at the beginning of the negotiation as it will focus customers only on the economic aspects of the negotiation and not on the true value of your offer. If you have a range of offers that would meet the customers’ needs, or you need to know what their budget is, there are two possible approaches: Present a mid-range price so you can go up or down depending on the customer’s reaction. Alternatively, you could present the most expensive solution and come down until you agree on an acceptable price.25

• Connect the price to the intangible components of your offer: Frequently, a seller’s lack of confidence in what they are offering emerges when they present the price. Many of our colleagues have difficulty in presenting their quote because they are not convinced that their offer is worth that price. In our experience, this generally happens because the salesperson is considering only the material aspects of the offer system, and is unable to quantify in economic terms the rest of the elements that comprise the whole. This is especially true for those who work in areas related to creativity, communication, art, or entertainment. Bear in mind that in this case the price–value relationship is closer and if we only take into consideration the material output we might risk finding ourselves with a dearth of arguments when bargaining. Remember that in this sector, especially, the price is based overwhelmingly on the intangible elements of the offer. Any price calculated purely on the basis of the (few) material elements risks devaluating our proposal.26 For example, the material output of a one-hour counseling session would amount to a brief chat with the client. If we were to evaluate the time only, then the many years of training and the experience condensed in that short meeting would be neither recognized nor rewarded and neither would the benefits accruing to the client.

Manage Requests for Discount in an Ethical Way

Given that the marketing strategies of most companies include discount policies based on various parameters, such as quantities purchased, customer types, or seasonal demand, it felt right to dedicate an entire section to this topic.

Discount is sometimes important enough to take on a central role in an offer, as though it were not actually our products and our services being offered to customers but the discount itself. Discount is also often the most effective (and swiftest) weapon in the battle against competitors!

“I’ll give you a further 5 percent discount on my competitor’s price if you buy from me” is a phrase that many sellers use more or less directly. However, you should ask yourself what you gain from this method in the medium to long term. Does the market in which we operate really require such an approach or are we, as W. Brian Arthur argues, merely impoverishing our relationships and causing the sector to shrink?

The preceding pages will have provided you with the knowledge to answer these questions, so we now wish to propose a valid approach to those times when you find yourself faced with customers who are set on obtaining discount and only intend to make a purchase if they obtain it. There are at least three pitfalls involved in ceding discount lightly, some of which have already been mentioned, but it is useful to summarize them here:

• Generally, the price embodies the value of the entire offer system. If you lower the price for no reason then the whole system is devalued, yourself included;

• If you lower your initial price you give the impression of having purposely inflated it beforehand, and hence of having deceived your customer;

• From the moment you give discount, you are basing the whole trade relationship on purely economic terms. The more purchases your customer makes the more discounts you will be obliged to concede and you will soon find yourself in the situation that W. Brian Arthur would describe as that of decreasing returns.

Of course, discount can sometimes be a problem solver: When we have failed to establish a good relationship with the customer or something goes wrong during the bargaining, it can kick-start a stalled negotiation. The result will probably be good that one time, but Ethical Salespeople know that selling is a process that unfolds over a longer period and that relationships, like success, should be measured in the medium to long term. They know that customers who are forced to buy through discount are unlikely to be loyal.

We also want to warn you against thoughts like “I’ll sell myself down a little today, then I can push the price up tomorrow” or likewise, “I can give a discount to convince the customer to make the first purchase, but then I will make it up in subsequent sales.” Trust us; once your worth has been linked to a particular quote it will be very difficult, if not impossible, to persuade someone to accept a higher price. “Why should I pay more for the same thing now?” the customer will rightly ask. Once you have adopted a competitive strategy based on decreasing returns, it will be difficult to chart a different course.

If you are faced with customers who want to strike a deal based on the price at all costs, or whose pride would suffer if they were to close the deal without securing any discount, choose to throw in a gift or add an additional service, but do not change the price! This approach will leave the perceived value intact while satisfying your hard-bargaining customer.

Stay focused on the value you are offering, underline the benefits for the customer and stick fearlessly to your price. We will give you some further tips on this topic in the next phase, and help you find out how to tackle customers who exclaim, “It’s too expensive!”

Exercises

• Do you know how to present the price? Using the benefits of the product or service that you identified in the last exercise, prepare a presentation of the price using the following pattern:

1. One or two benefits

2. Price

3. Further benefits

• Can you manage requests for discount? Now consider what extra you might offer to a customer demanding discount (free samples, quantity, services) instead of discount itself.