Introduction

The need to be safe, which in practice means the need to be able to operate or function with as many wanted and as few unwanted outcomes as possible, is paramount in every industry and indeed essential to all human activity (Hollnagel, 2014). It is obviously of particular concern in the many safety critical industries, where losing control of the process can lead to severe negative consequences. The examples of nuclear power generation and aviation immediately come to mind. But the need to be safe is present in all other industries as well, including healthcare and mining.

The pursuit of safety must obviously correspond to the nature of the systems and processes that are characteristic of an industry, in particular the ways in which things work and the ways in which they can fail. In the dawn of industrial safety – in the last half of the 18th century, when widespread use of steam engines heralded the second industrial revolution – the main problem was the technology itself (Hale and Hovden, 1998). The purpose of safety efforts was at first to avoid explosions and prevent structures from collapsing, and later to ensure that materials and constructions were reliable enough to provide the required functionality. After the end of the Second World War (1939–45), safety concerns were enlarged to include also the human factor. At first, human factors were about how people could be matched to technology and later about how technology could be matched to people. In both cases the main concern was productivity rather than safety. The full impact of the human factor on safety only became clear in 1979 following the accident at the nuclear power plant at Three Mile Island, which demonstrated how human activities and misunderstandings themselves could be safety critical. Following that, the notion of human error became so entrenched in both accident investigations and risk assessments that it often overshadowed other perspectives (Senders and Moray, 1991; Reason, 1990). In the late 1980s, safety concerns got a new focus when it was realised that organisational factors also were important. The triggering cases were the loss of the space shuttle Challenger and the accident at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl, both in 1986. The latter also made safety culture an indispensable part of safety efforts (INSAG-1, 1986).

Looking back at these developments, the bottom line is that safety thinking must correspond to actual work in actual working conditions, that is, to what we can call the industrial reality. Simple methods, and simple models, may be appropriate for simple types of work and working environments, but cannot adequately account for what happens in more complicated work situations. The industrial reality is unfortunately not stable but seems forever to become more difficult to comprehend. So while safety efforts in the beginning of the 20th century only needed to concern themselves with technical systems, it is today necessary to address the set of mutually dependent socio-technical systems that is necessary to sustain a range of individual and collective human activities. Another important lesson is that the development of safety methods always lags behind the development of industrial systems and that progress usually takes place in jumps that are triggered by a major disaster. It would, however, clearly be an advantage if safety thinking could stay ahead of actual developments and if safety management could be proactive. Resilience engineering shows how to do that.

Safety Culture

At the present time, industrial safety comprises different types of effort with different aims. Some focus on making the technology as reliable as possible. Others look to the human factor, both in the sense of the basic ergonomics of the workplace, and in the sense of creating suitable work processes and routines. Yet others focus on the organisational factor, in particular the safety culture. Indeed, safety culture has in many ways replaced ‘human error’ as the most critical challenge for safety management. This has created a widespread need to be able to do something about safety culture, which has not gone unheeded – despite the fact that safety culture as such remains an ill-defined concept.

The commonly used way of describing safety culture relies on a distinction between different levels, usually five (Parker, Lawrie and Hudson, 2006). The levels are treated as if they represent distinct expressions of safety culture although in practice they stand for representative positions on a continuum. A characterisation of the five levels is provided in Table 12.1. In recent writing, the generative level has been renamed the resilient level (Joy and Morrell, 2012), although the justification for that is not completely clear.

Table 12.1 The five levels of safety culture

Level of safety culture |

Characteristic |

Typical response to incidents/accidents |

Generative (resilient) |

Safe behaviour is fully integrated in everything the organisation does. |

Thorough reappraisal of safety management policies and practices. |

Proactive |

We work on the problems that we still find. |

Joint incident investigation. |

Calculative |

All necessary steps are followed blindly. |

Regular incident follow-up. |

Reactive |

Safety is important, we do a lot every time we have an accident. |

Limited investigation. |

Pathological |

The organisation cares more about not being caught than about safety. |

No incident investigation. |

An important assumption underlying the idea of safety culture is that it always is in the organisation’s interest to move to a higher level of safety culture. The motivation for wanting to improve the safety culture is, of course, that a degraded safety culture is assumed to be a major reason for the occurrence of accidents and incidents. But if we, for the sake of discussion, accept that assumption – noting in passing that it by no means has been independently proven – then it is only fair to acknowledge that there also are a number of arguments against making the journey. One is that it incurs a cost, and that it indeed may be rather expensive. A second is that moving from the reactive or calculative to the proactive or generative levels means that the organisation in addition to dealing with the certain, that which actually happens, also has to deal with the potential, that which could happen. This introduces a risk and requires that the organisation looks beyond the short term to the long term. That, however, does not fit the agenda of all organisations (Amalberti, 2013). In some cases it may be justified to remain calculative for a while, for instance to build up the resources that are necessary to survive in the long run. In that sense, the different levels of safety culture can be seen as corresponding to different priorities in the organisation’s safety-related efficiency-thoroughness trade-off (Hollnagel, 2009).

About Safety Culture

The first definition of safety culture was the result of the workshop at the International Atomic Energy Agency in 1986, in the wake of the accident at Chernobyl. Here safety culture was defined as ‘(t)hat assembly of characteristics and attitudes in organizations and individuals which establishes that, as an overriding priority, nuclear plant safety issues receive the attention warranted by their significance’ (INSAG-1, 1986). This is quite similar to the definition of organisational culture as ‘a pattern of shared basic assumptions invented, discovered, or developed by a given group as it learns to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration’ proposed by Edgar Schein in the 1980s (for example, Schein, 1992).

Since then a number of surveys of safety culture have tried to define the concept more precisely as well as to account for its role in safety, but with a rather disappointing outcome. Guldenmund (2000) began a review of theories and research on safety culture in a special issue of Safety Science as follows:

In the last two decades empirical research on safety climate and safety culture has developed considerably but, unfortunately, theory has not been through a similar progression.… Most efforts have not progressed beyond the stage of face validity. Basically, this means that the concept still has not advanced beyond its first developmental stages.

Other surveys reach similar conclusions, for instance Hopkins (2006) and Choudhry, Fang and Mohamed (2007). Given this state of affairs, one could do worse than adopt the above mentioned IAEA definition of safety culture.

Becoming Safe

The description of the five levels of safety culture almost forces people to think of safety culture development as a transition from one level or from one step of the ladder to the next (Parker, Lawrie and Hudson, 2006). The very description of the levels implies two things. First, that progress means moving up the levels, while deterioration means moving down. Second, that any change has to be done level-by-level (leaving out the possibility of a complete drop from one level to the bottom, of course).

In order to use safety culture developments to improve safety, we should be able to answer the following practical questions:

• First, how can we determine an organisation’s current level of safety culture? This is important both to find out what the starting point is and when the goal or ‘destination’ has been reached. Otherwise a change might simply be completed when all the available resources – or the allotted time – have been spent. An answer to the first question must be unambiguous and operational. It must also refer to some kind of articulated theory rather than simply rely on established practice or social consensus. The answer is finally a prerequisite for being able to maintain a level, since maintenance requires that a change can be detected.

• Second, what is the goal in the sense of how good should the safety culture of the organisation be? Is the final goal that the organisation has a generative/resilient safety culture or could something less ambitious be acceptable? And what is a generative/resilient safety culture anyway, that is, how can it be determined that an organisation has reached that level?

• Finally, what kind of effort does it take to change or move from one level to the next? Since the differences between the levels clearly are qualitative rather than quantitative, it is unlikely that a repetition of the same type of effort cumulatively will be sufficient to move an organisation from the lowest to the highest level. Related questions are how much effort is needed, how long time a change will take, whether the effects are immediate or delayed, how much effort it takes to remain at a given level, and what the ‘distances’ between the levels are – since it would be unreasonable to assume that the levels are equidistant.

A straightforward solution for how to improve safety would be to use a common development approach where change was guided or managed by an external agent (management). Change would in this way be the result of an active personal desire rather than a need to comply with management goals or requirements. In this way safety culture could be changed by ‘winning hearts and minds’ (Hudson, 2007).

While focusing on changes to individual behaviour may be consonant with the notion of organisational culture, it also means that individual performance and safety culture become entangled. It is therefore not really the organisation that moves from one level to the next, but rather the individuals that change their attitudes to their work in terms of personal responsibility, individual consequences and proactive interventions. Strictly speaking this means that a measure of the level of safety culture refers to some composite expression of the attitudes of the individuals rather than to an organisational characteristic. It also assumes that the organisation is homogeneous and that all its members share the same attitudes or the same culture. This clashes with the fact that all organisations are heterogeneous, which means that some parts (divisions, departments, special functions) may work in one way while others may work in another.

The final goal, that an organisation functions so that most things go right and few things go wrong, can also be achieved in other ways than by changing the safety culture. Instead of explaining performance as determined by the level of safety culture, we may look at the characteristics of organisational performance as such. This approach is used both by the High Reliability Organisation (HRO) school of thinking (Roberts, 1990; Weick, 1987) and resilience engineering (Hollnagel, Woods and Leveson, 2006; Hollnagel et al., 2011). In the following, we shall consider the implications of resilience engineering for understanding how safe performance can be brought about.

Engineering a Culture of Resilience

The most important difference between resilience engineering and the common safety approaches is the focus on everyday successful performance. This is captured by the distinction between two safety concepts, called Safety-I and Safety-II (Hollnagel, 2014; ANSI, 2011). Safety-I defines safety as the absence of accidents and incidents, or as the ‘freedom from unacceptable risk’. Safety-II defines safety as the ability to succeed under varying conditions. This is, of course, consistent with the hypothesis that a better safety culture leads to a reduction in incidents and accidents. But rather than propose an explanation based on a single factor or dimension, resilience engineering looks to the nature of individual and organisational performance. It is more precisely proposed that a resilient organisation – or system – must be able:

• to respond to regular and irregular variability, disturbances and opportunities;

• to monitor that which happens and recognise if something changes so much that it may affect the organisation’s ability to carry out its current operations;

• to learn the right lessons from the right experience; and

• to anticipate developments that lie further into the future, beyond the range of current operations.

For any given organisation the proper mix or combination depends on the nature of its operations and the specific operating environment (business, regulatory, environmental, social and so on). The four abilities are furthermore mutually dependent. For instance, the effectiveness of an organisation’s response to something depends on whether it is prepared (that is, able to monitor) and whether it has been able to learn from past experience.

The four abilities can clearly be developed to different degrees for a given organisation. And since each ability can be further specified by means of underlying or constituent functions, this can be used both to find how well an organisation currently is doing and to define how well it should be doing. A concrete approach to that is the Resilience Analysis Grid (RAG, cf., Hollnagel, 2010; ARPANSA, 2012), which can be used to assess how well an organisation performs on each of the four abilities at a given time. The same assessment can be used to propose concrete ways to develop specific sub-functions of an ability – without forgetting for a moment that the abilities are mutually dependent. The potential to develop the four abilities therefore offers a useful alternative to the safety journey, which in the following will be called the road to resilience.

In contrast to the development of safety culture, resilience engineering is not about reaching a certain level but about how well the organisation performs as such. Resilience does not characterise a state or a condition – what a system is – but how processes or performance are carried out – what an organisation does. Becoming resilient thus differs from becoming safe by being continuous rather than discrete. It is more precisely about maintaining a balance among the four abilities that is appropriate for a certain type of activity and a certain type of situation. If, for instance, an organisation focuses primarily on responding, as in handling unforeseen or difficult situations, and therefore neglects monitoring, then it is not considered to be resilient. The reason is simply that neglecting monitoring will increase the likelihood that performance is disturbed by unforeseen events, which will lead to reduced productivity and/or jeopardising safety.

The Road to Resilience

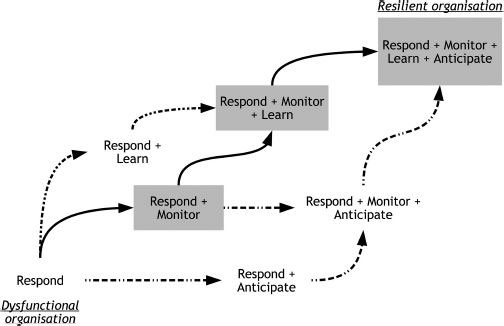

In order to describe the road to resilience it is convenient to consider two extremes. One is a dysfunctional or pathological organisation that functions rather badly and the other a resilient organisation that functions well.

1. A dysfunctional organisation responds to what happens in a stereotypical or scrambled manner, and cares neither about monitoring, learning or anticipating. The ability to respond is fundamental since an organisation (or a system or an organism) that is unable to do so with reasonable effectiveness sooner or later will become extinct or ‘die’ – in some cases literally. An organisation that only is able to respond is reactive, and the absence of learning means that it constantly is taken by surprise.

2. A resilient organisation is able to respond, monitor, learn and anticipate. It is furthermore able to do all of these acceptably well, and to manage the required efforts and resources appropriately. But unlike the levels of safety culture, there is no ceiling for the abilities. It is always possible to respond more effectively or quickly, to improve the monitoring, to learn more and to anticipate better.

The practical question is how an organisation can change from being dysfunctional to become resilient. Since the four abilities all need to be improved, it would immediately seem as if there were at least four possible roads to resilience. The four ‘roads’ could be found by considering various combinations of the four resilience capabilities, and the transitions between them. By thinking a little more about the four abilities, it can be argued that one road to resilience is more sensible – and thereby also more effective – than the others.

The Dysfunctional Organisation

The road to resilience in principle starts from the dysfunctional organisation, that is, an organisation that basically only is able to respond. While such an organisation is imaginable (such as a financial institution that is ‘too large to fail’ or a software company that does not recognise changes in the use of computing machinery), it cannot survive for long unless almost nothing happens around it. While a respond-only organisation is possible, the same does not go for the other three resilience abilities, for example, a monitoring-only, a learning-only or an anticipation-only organisation. The reason is simply that an organisation or a system cannot survive without the ability to respond, even if it only is opportunistically.

This leaves three possible ways forward, namely to enhance either the ability to monitor, to learn or to anticipate. While there are arguments for and against each of them, the overriding criterion for how to proceed should be that it enhances the organisation’s ability to respond.

Organisations that Can Respond and Monitor

The best way to enhance the ability to respond is to develop the ability to monitor. Monitoring allows an organisation to detect developments and disturbances before they become so large that a response is necessary. This will on the one hand enable the organisation to prepare itself for a response, for instance by reallocating internal resources or by changing its mode of operation, and on the other allow early responses to weak signals. A trivial example of that is proactive maintenance – which is better than scheduled maintenance and far better than emergency repairs. Responding at an early stage in the development of an event will generally require fewer resources and take less time, although it also incurs the risk that the response may be inappropriate or even unnecessary. Yet even that is preferable to operating in a reactive mode only.

As an example, consider an organisation where the conditions for everyday operation and production are unstable, and where there may be significant fluctuations in the supply of parts, of resources, in the quality of raw materials, in the environment and so on. In such cases it is important to keep an eye on the conditions that are necessary for safe and effective performance, hence to improve monitoring as the first step on the road to resilience.

Organisations that Can Respond, Monitor and Learn

For an organisation that is able to respond and to monitor, the next logical step is to develop the ability to learn. Learning is necessary for several reasons. The most obvious is that the environment is changing, which means that there always will be new and unexpected situations or conditions. It is important to learn from these and to look for patterns and regularities that can improve the abilities to respond and to monitor. Another important reason is that the ability to respond always will be limited. It is simply not affordable to prepare a response for every event or for every possible set of conditions (Westrum, 2006). This means that the organisation every now and then will not know how to respond. It is clearly important to learn from these, to evaluate whether they are unique or likely to occur again, and to use that to improve both responding and monitoring. Similarly, the organisation should also learn from responses that went well, since it always is possible to make improvements. The organisation can use this experience to improve the precision of responses, the response time, the set of cues or indicators that are monitored and so on.

The Resilient Organisation

At the point when an organisation can respond, monitor and learn sufficiently well, the ability to anticipate should be developed. Anticipation can more precisely be used to enhance the abilities to monitor (suggesting which indicators to look for), to respond (outlining possible future scenarios) and to learn (prioritising different lessons). Learning can be used to improve the ability to respond, to select appropriate indicators and cues and also to hone the imagination that provides the basis of anticipation. Monitoring can primarily be used to improve the ability to respond (increased readiness, preventive responses). And responding can provide the experience that is necessary to improve learning as well as anticipation.

This altogether means that an organisation that wants to improve, to become more resilient, must carefully choose how and when to develop each of the four abilities. It is not recommended to make a wholesale change or improvement, in the same way that the safety journey envisions a step change in the level of safety culture. An organisation must instead first determine how well it does with regard to each of the four abilities – by carefully assessing the functions that contribute to each ability – and then plan how to go about developing them. Such plans must take the mutual dependencies into account and look for the most efficient means rather than rely on ready-made solutions. In some cases an ability or its constituent functions may be developed by means of technical improvements, for example, better sensors or more powerful ways of analysing measurements. In others it may be the human factor or organisational relations that need working on. In yet other cases it may be organisational functions such as planning, event analysis and training. And there may finally be cases where attitudes, or even safety culture, are of instrumental value.

Conclusions

The above considerations are summarised in Figure 12.1, which shows the main road to resilience. The road does not necessarily start by the dysfunctional organisation. Although such an organisation theoretically represents an extreme, it would not be able to survive for long in practice, and is therefore not a reasonable point of departure. The road rather starts from an organisation that is able to respond and monitor, that is, able to maintain an existence even if it is not the ideal.

Figure 12.1 The road to resilience

The road ends by the resilient organisation, and the main path is shown by the dark lines in Figure 12.1. The progress is made by first developing the ability to learn followed by the ability to anticipate. But the organisation should also reinforce and improving already working abilities at the same time as it develops new ones. Progress is, however, neither simple or ‘mechanical’. It requires an overall strategy as well as a ‘constant sense of unease’ (Nemeth et al., 2009) that can be used to make the best of the available means. The organisation’s progress should be followed continuously so that any unanticipated development – or lack of development – can be caught early on and addressed operationally.

The Three Questions and The Road to Resilience

The consequences of the road to resilience can be summarised by looking at how the three questions were answered.

In terms of how can we determine the quality of the current performance of an organisation, resilience engineering proposes that this is done by looking at the four abilities and their underlying or constituent functions. There is already one practical technique for doing that, namely the Resilience Analysis Grid, which is derived from an articulated description of what resilience is.

In terms of setting the goal, resilience engineering does not prescribe a final solution. Instead, each organisation must decide how resilient its performance needs to be, expressed as differential levels of the four abilities. This is a pragmatic rather than a normative choice that depends heavily on what the organisation does and in which context it must work. Unlike the notion of safety culture as expressed by the five level model, there is no ceiling for resilience. An organisation can always improve and become better at what it does – in terms of productivity, safety, quality and so on.

Finally, with regard to how much effort it takes to improve resilience, the specification of the four abilities in terms of their constituent functions enables a high degree of realism. For each constituent function the possible means to make the desired change can be developed and evaluated in terms of cost, risk and so on. Since the constituent functions of the four abilities may differ significantly among functions, there is no standard or generic solution. But once the functions have been analysed and the goals defined, a variety of well-known and proven approaches will be available.