A Framework for Learning from Adaptive Performance

There is often a difference between the way work is expected to be carried out (work as imagined) and the way it is actually carried out (work as done) in order to cope with complexity in high-risk work (for example, Hoffman and Woods, 2011; Hollnagel, 2012; Loukopoulos, Dismukes and Barshi, 2009). Events and demands do not always fit the preconceived plans and textbook examples, leaving nurses, air traffic controllers, fire chiefs and control room operators to ‘fill in the gaps’. Examining practitioners’ work shows a story of people coping with complexities by continuously adapting their performance, often dealing successfully with disturbances and unexpected events. Such stories can provide important information for organisations to identify system resilience and brittleness.

The literature on studies of people at work is replete with examples of sharp-end personnel adapting their performance to complete tasks in an efficient and safe way (Cook and Woods, 1996; Cook, Render and Woods, 2000; Koopman and Hoffman, 2003; Nemeth et al., 2007; Woods and Dekker, 2000). However, compensating for the system design flaws through minor adaptations come at a cost of increased vulnerability as systems are not fully tractable and outcomes are difficult to predict (Cook et al., 2000; Hollnagel, 2008; Woods, 1993). The terms sharp end and blunt end are often used to describe the difference between the context of a particular activity where work is carried out and factors that shape the context (Reason, 1997; Woods et al., 1994). The values and goals affecting sharp-end and blunt-end adaptive performance can be understood in terms of trade-offs such as optimality-brittleness, efficiency-thoroughness and acute-chronic (Hoffman and Woods, 2011; Hollnagel, 2009). Based on a number of overarching values and goals set by the blunt-end concerning effectiveness, efficiency, economy and safety, the sharp-end adapts its work accordingly. Effects of managerial level decisions, such as updating or replacing technical systems and procedures, are not always easy to predict and may lead to unintended complexity that affect the sharp-end performance negatively (Cook et al., 2000; Cook and Woods, 1996; Woods and Dekker, 2000; Woods, 1993).

Adaptations at the sharp-end have also been described as representing strategies (Furniss et al., 2011; Kontogiannis, 1999; Mumaw et al., 2000; Mumaw, Sarter and Wickens, 2001; Patterson et al., 2004). Strategies are adaptations used by individuals to detect, interpret or respond to variation and may include, for example, informal solutions to minimise loss of information during hand-offs or compensating for limitations in the existing human-machine interface (Mumaw et al., 2000; Patterson et al., 2004). Adaptations have also been characterised in terms of resilience characteristics, based on analyses of activities in terms of sense-making and control loops (Lundberg, Törnqvist and Nadjm-Tehrani, 2012).

Over time adaptations can have a significant effect on the overall organisation (for example, Cook and Rasmussen, 2005; Hollnagel, 2012; Kontogiannis 2009). Each individual decision to adapt may be locally rational, but the effects on the greater system may not have been predicted and far from what was intended. Although vulnerabilities may have been exposed they may not have been recognised as such when organisations do not know what to look for. Rasmussen (1996) describes this migrating effect in terms of forces, such as cost and effectiveness, which systematically push work performance toward and possibly over the boundaries of what is considered to be acceptable performance from a safety perspective.

In this chapter a framework to analyse sharp-end adaptations in complex work settings is presented. We argue that systematic identification and analysis of adaptations in work situations can be a critical tool to unravel important elements of system resilience and brittleness. The framework should be seen as a tool to be integrated into safety management and other managerial processes as it fills a terminology gap. The framework has been developed based on an analysis of a collection of situations where sharp-end practitioners have adapted (resulting in both successes and incidents), across domains that include healthcare, transportation, power plants and emergency services (Rankin, Lundberg, Woltjer, Rollenhagen and Hollnagel, 2013). The framework supports retrospective, real-time and proactive safety management activities. Retrospective analysis is done by using the method for analysis in the aftermath of events where an incident can be seen as a by-product of otherwise successful adaptive performance. The framework can further be used protectively to collect examples and identify patterns to monitor system abilities, predict future trends and appreciate ‘weak signals’ indicating potential system brittleness. In this chapter the framework is extended with a model of the interplay between framework categories using a control loop, which is demonstrated using two examples, one in crisis management and one in a health care setting. The illustration of the examples show how analysis of adaptations provides a means to improve system monitoring and thereby increase system learning. The framework has been applied as a learning tool but could in the future provide structure for teams and managers to ‘take a step back’ during real-time performance and examine if their strategies are having the desired effect, similar to what Watts-Perotti and Woods (2007) describe as broadening opportunities by blending fresh perspectives, revising assessments and replanning approaches.

A Framework to Analyse Adaptations in a Complex Work Setting

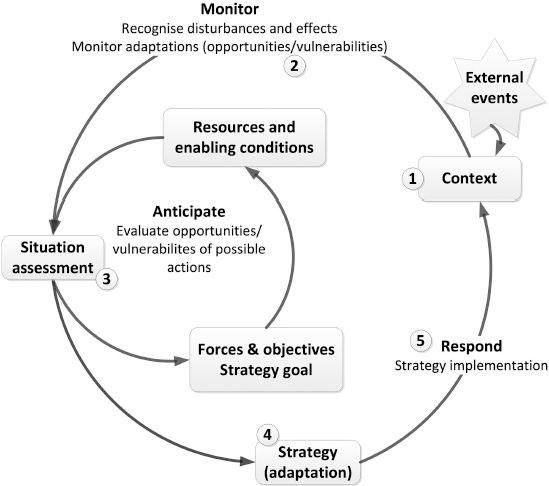

The strategies framework describes the context in which an adaptation takes place, enablers for the adaptation and the potential adaptation reverberations in the system. An adaptation is in this framework referred to as a strategy. The context is described through identification of the current system conditions, the individual and team goals, as well as the overarching organisational objectives and forces which may play a role in the response. Resources and other enabling factors define the conditions necessary for implementation of the strategy. The potential reverberations of the strategy on the system are captured through an analysis of system resilience abilities (Hollnagel, 2009) and the sharp and blunt end interactions. Table 6.1 provides an overview of these framework categories and Figure 6.1 demonstrates how the categories relate in a dynamic environment. The overview is followed by two examples of how the framework can be used to analyse adaptations in everyday operations.

Table 6.1 Framework categories and description

Category |

Description |

Strategy |

Adaptations to cope with a dynamic environment. Strategies may be developed and implemented locally (sharp-end) or as part of an instruction or procedure enforced by the organisation (blunt-end), or both. To examine the adaptation effect on the system, strategy opportunities and vulnerabilities are identified. |

Context |

The factors that influence the system’s need to adapt, e.g., events (disturbances), current demands. Feedback from the context provides input for the controller to assess the situation and prepare responses. Feedback may be selective or incomplete depending on system design and context. |

Forces and objectives |

Information on the manifestation of organisational pressures in a particular context. Forces are pressures from the organisation (e.g., profit, production) that may affect intentions and performance of the adaptation. Objectives are the organisation’s overarching goals. |

Resources and enabling conditions |

Enablers for implementation of a particular strategy. Conditions may be ‘hard’ (e.g., availability of a tool) and ‘soft’ (e.g., availability of knowledge). This category extends the analysis of context in that it focuses on what allows (or hinders) the strategy to be carried out. This analysis can be further used to investigate information on the systems flexibility. |

Strategy goal |

The identification of what the strategy is aimed at achieving. This can also be viewed as an outcome that the behaviour is aimed at avoiding. |

Resilience abilities |

Includes the four cornerstones; anticipating, monitoring, responding and learning, as described by Hollnagel (2009). The categories help identify a pattern of system abilities (and inabilities) with reference to the type of disturbances faced. |

Sharp and blunt-end interactions |

Recognition and acknowledgement of the strategy in different parts of the distributed system. A system must monitor how changes affect work at all levels of an organization, i.e., a learning system will have well-functioning sharp-end-blunt-end interactions. |

In Figure 6.1 a model is presented, demonstrating the interplay between the categories that constitute the framework. Building on the principle of a basic control loop (Hollnagel and Woods, 2005; Lundberg et al., 2012) we aim to recognise the dynamics of a socio-technical environment. The loop can be used to illustrate processes at different layers, such as the sharp- and blunt-end, of the system. Sharp- and blunt-end relations should be seen as relative rather than absolute as every blunt-‘end’ is the sharp-‘end’ of something else.

System variability may originate in external events such as changes or disturbances in the working environment or in natural variations in human and technical system performance. The context is shaped by the forces, objectives and demands on the system and may be affected by disturbances (no. 1, Figure 6.1). Monitoring of system feedback is required to assess what actions to take, and if there is a need to adapt (no. 2, Figure 6.1). A situation assessment is made based on the feedback provided by the system, organisational forces and objectives, strategy goals, identification of an appropriate strategy and resources available to implement the strategy (no. 3, Figure 6.1). The inner loop illustrates how the combined factors play a role in determining an appropriate action and that several options may be assessed prior to taking action. The trade-offs made can be described in terms of anticipating the opportunities and vulnerabilities that the adaptation may create. The process of recognising and preparing for challenges ahead has previously been described as the future-oriented aspect of sensemaking, or anticipatory thinking (Klein, Snowden and Pin, 2010). Attention is directed at monitoring certain cues, and responses are based on what is possible within the given context. Situation assessment and identification of possible responses is thus part of the same process and based on the current understanding (Klein, Snowden, Pin, 2010) (no. 3, Figure 6.1). The adaptation (no. 4, Figure 6.1) leads to changes in the environment which will affect the context. (no. 5, Figure 6.1).

The inner loop process is not necessarily explicit or available for full evaluation, particularly not in hindsight – a difficulty commonly referred to as hindsight bias (Fischoff, 1975; Woods et al., 2010). The analyst should therefore be cautious and avoid such biases when identifying and analysing the input in the inner loop to examine what shapes the situation and the selection of response (retrospective analysis). Trends and patterns of these factors can provide important information on what conditions and factors should be monitored to assess system changes in future events (proactive analysis). Balancing opportunities and vulnerabilities is not done on complete information at the sharp-end or the blunt-end and for sharp-end adaptations the time for interpretation is often restricted. Decisions and actions taken are based on the limited knowledge and resources available in a specific situation, that is, they are ‘locally rational’ (Simon, 1969; Woods et al., 2010).

Figure 6.1 A model to describe the interplay between the framework categories

Demonstrating the Framework – Two Cases

Two cases are used to demonstrate how the framework can be applied to analyse situations where the system has to adapt outside formal procedure to cope with current demands. The cases are further visualised using the control loop model. The analysis focus is on how systems may learn from the analysis of adaptive performance and why monitoring everyday adaptations is important. In the first case a crisis command team adapts to a disturbance by re-organising the team, but fails to monitor the effects of the adaptation which subsequently contributes to several system vulnerabilities. The second case describes a situation where a team at a maternity ward successfully adapt to cope with high workload. The adaptation is acknowledged at managerial levels demonstrating how a system can learn from a sharp-end adaptation. A summary of the framework analysis can be found in Table 6.2 following the case descriptions and analysis.

Case 1 Reduced Crisis Command Team

In this example a crisis management team is forced to adapt to the loss of important functions. The example comes from a Swedish Response Team simulation (Lundberg and Rankin, 2014; Rankin, Dahlbäck and Lundberg, 2013) based on a real event: the 2007 California Wildfires. The team’s overall aim is to support the Swedish population of 20,000 in the affected area by providing information and managing evacuations. One of the team’s main tasks is to collect and distribute information regarding hazardous smoke in the area. This includes information on the severity of the smoke, required protection and where to get help if required.

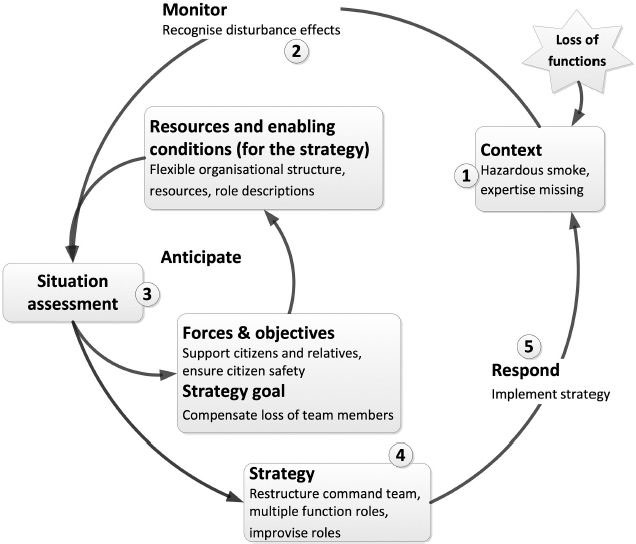

Following a weather disturbance the command team is unexpectedly reduced from 18 to 11 members. The team responds rapidly by restructuring the team’s functions and roles (no. 1, Figure 6.2). The disturbance and its effects were assessed by the team, led by the chief commander (no. 2, Figure 6.2). Adaptation to the new situation was enabled by the team’s flexibility, which is part of the organisation design. To manage all key functions several people took on multiple roles. To assist the team in taking on roles outside their field of competence they used role descriptions found in the organisation’s procedures (no. 3, Figure 6.2). The team was subsequently restructured, with several team members taking on multiple roles as well as roles outside their field of competence (no. 4, Figure 6.2).

The reverberations of the adaptation in this situation are depicted in Figure 6.3. Initially, the system responded efficiently to the initial disturbance and adapted by re-organising the command team structure to cover all necessary functions (no. 1, Figure 6.3). However, the organisation was now functioning in a fundamentally different way, creating new system vulnerabilities through an inefficient organisational structure with unclear responsibilities. The example demonstrates that adapting the team according to procedure does not necessarily mean that procedures are resources for action and that applying procedures successfully requires expertise and of how to adapt it to local circumstances (Dekker, 2003). The example demonstrates that adapting the team according to procedure does not necessarily mean that procedures are resources for action and that applying procedures successfully requires expertise and of how to adapt it to local circumstances (Dekker, 2003). The vulnerabilities of this situation were not detected by the team, or at least not explicitly acknowledged, and critical information was lost, i.e., as the system adapts there is a failure to monitor how re-organisation affected the ability to adequately carry out tasks (no. 2, Figure 6.3). The difficulties in successfully fulfilling tasks are not completely undetected as joint briefings are held and incoming information is questioned (no.’s 3 and 4, Figure 6.3). However, strategies aimed at ensuring that tasks are carried out adequately are not sufficient to compensate for and unravel misinterpretations. Several critical aspects such as unclear responsibilities are overlooked and conflicting information within the team goes undetected (no. 5, Figure 6.3) (Lundberg and Rankin, 2014, Rankin, Dahlbäck and Lundberg, 2013). Although a procedure was in place, the team lacked the ability to adapt it to the local circumstances.

Figure 6.2 Case 1 – Initial disturbance forcing the command team adapt

Figure 6.3 Failure to fully adapt and cope with the new situation

Case 2 High Workload at the Maternity Ward

A remarkably large number of births one evening led to chaos at the maternity ward. The ward was understaffed and no beds were available for more patients arriving. Also, patients from the emergency room with gynaecological needs were being directed to the maternity ward as the emergency room was overloaded. To cope with the situation one of the doctors decided to send all fathers home of the newborn babies home. Although not a popular decision among the patients this reorganisation freed up beds, allowing the staff to increase their capacity and successfully manage all the patients and births. After this incident an analysis of the situation was performed that resulted in a new procedure for ‘extreme load at maternity hospital’.

The system demonstrated several important abilities contributing to system resilience as it uses its adaptive capacity to respond to and learn from the event, which has been illustrated in Figures 6.4 and 6.5. Initially a large amount of patients are streaming into the ward, changing the contextual factors (no. 1, Figure 6.4). Based on an assessment of the current system status, the objectives and goals and the resources available, the doctor in charge decides to reorganise the resources to increase the capabilities necessary (no.’s 2, 3 and 4, Figure 6.4).

The strategy is realised and as a result the system has enough resources to cope with the high workload (no. 3, Figure 6.4, no. 1 Figure 6.5). Following the incident the managerial levels of the organisation detect and assess the occurrence, identifying system brittleness during high workload (no. 2, Figure 6.5). Based on the success of the sharp-end adaptation the blunt-end introduces a new procedure for managing similar situations (no. 3, Figure 6.5). The system thus demonstrates the ability to learn through well-functioning sharp- and blunt-end interactions (no. 4, Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.4 Case 2 – High workload at maternity hospital requires reorganisation

Figure 6.5 Case 2 – System learning through system monitoring and introduction of new procedure

Summary

The table overleaf summarises the framework analysis of the two cases described previously (Table 6.2).

Adaptations may change the system’s basic conditions in unexpected and undetected ways, as shown in the first case. This phenomenon has previously been identified in studies of sharp-end adaptation as new technology is introduced leading to unforeseen changes in the work environment (Cook et al. 2000, Koopman and Hoffman 2003, Nemeth, Cook and Woods 2004). Hence, adaptations must be analysed not only in terms of their effects on the system, but also in terms of the new system conditions and the vulnerabilities (and opportunities) the changes may have generated. Although sharp-end adaptations are necessary to cope with changing demands in complex systems, they may also ‘hide’ system vulnerabilities by successfully adapting their work to increase efficiency and safety of the system. Recognising these shifts in work and what creates them provides necessary information to understand the operational environment and manage safety in a proactive way. An example of this is given in the second case where a sharp-end adaptation is acknowledged, recognised at managerial levels and used as a guide to improve the overall organisation.

Table 6.2 Summary of framework analysis

Category |

Case 1 Reduced Crisis Command Team |

Case 2 High Workload at the Maternity Ward |

Strategy |

Restructure command team by taking on roles outside one’s field of competence. Multiple function roles. Vulnerabilities include critical tasks not carried out, lack of domain knowledge, and lessened clarity of organisation structure. |

Prioritise beds for patients and mothers and send fathers home (sharp end). Create new ‘high workload’ procedure (blunt end). |

Context |

Forest fires causing hazardous smoke. Citizens in need of support. Loss of important functions. |

Inadequate resources due to many births. Patient sent from emergency room because overloaded. |

Forces and objectives |

Ensure citizen safety. Provide information to worried relatives. |

Provide care and ensure patient safety. Efficient resource management. |

Resources and enabling conditions |

Flexible organisational structure. Resources. Role descriptions. |

System structure to support reorganisation. Enough resources. |

Strategy goal |

Compensate loss of team members. |

Manage workload with current resources’ |

Resilience abilities |

Anticipating/Responding. |

Responding/Learning. |

Sharp- and bluntend interactions |

Blunt-end strategy enforced at sharp-end. |

Sharp-end strategy turns into blunt-end procedure. |

Monitoring Adaptations and their Enabling Factors

It is not only when adaptations critically fail (for example, incidents and accidents) that they are of interest to examine. All adaptations outside expected performance provide information about the system’s current state, its adaptive capacity and potential brittleness. Successful adaptations, failures to adapt or adapting to failure (Dekker, 2003) all provide key pieces of information to unravel the complexities of everyday work in dynamic environments.

By capturing everyday work and learning from adaptations it is possible to recognise what combinations of contextual factors, forces and goals create system brittleness as the system is forced to adapt. Similarly, the identification of adaptations allows insights into the individuals, teams and organisation’s adaptive capacities (resilience), and provides important information for system design. It also enables successful work methods to be incorporated into the system through design and procedures, ensuring the enabling conditions are available.

The cases described above demonstrate the importance of monitoring the effects of adaptations over time. As systems are modified to cope with current demands the system may change in ways not foreseen or understood. Previous examples of adaptations using the framework demonstrate how reverberations of adaptations in one part of the system may cause brittleness in other system parts (Rankin et al., 2011; Rankin et al., 2014). An example of this is a hospital ward where the sharp-end strategy of ordering medication with different potency from different pharmaceutical companies was developed. The reason for this was that medicine packages of different potency from the same company looked almost exactly the same, creating an increased risk of using the wrong medication in stressful situations. Ordering different potencies from different companies resulted in packaging with different colouring, allowing the nurses to use colour codes to organise the medication. However, one time the medication at one company was out of stock and the order was automatically placed at a different company. The nurses were not informed of this, creating a situation where expectations regarding colour codes could lead serious incidents or even fatal accidents.

Integrating Resilience Analysis with Accident and Risk Analysis Methods

The framework is intended be used to enhance current methods for learning from adverse events (accident and incident investigation) that build on defence-in-depth (Reason, 1997). Accidents are traditionally analysed through identification of events, contextual factors and failed barriers at the sharp-end and the go upwards through the organisation toward blunt managerial ends, analysing failed barriers through organisational layers (defence-in-depth). The method presented in this chapter could add to this by incorporating forces and contextual factors that enable success through adaptation. The framework has previously been applied in several industries (Rankin et al., 2011, 2014) demonstrating the possibility of an applied tool for identifying system resilience and brittleness across industries.

The examples described in this chapter show the importance of monitoring and subsequently learning from adaptations. This requires monitoring in the immediate, short and long term. Assessments using the framework can identify how adaptations may affect other parts of the system and change the system conditions, creating new opportunities and vulnerabilities.

Immediate monitoring requires ‘taking a step back’ during realtime performance to observe the effect of the strategy and to make adjustments as required, i.e. broadening (Watts-Perotti and Woods, 2007). This would have been valuable in case 1 where the command team fell short as they did not identify vulnerabilities resulting from the re-organisation. Further development together with practitioners can allow the framework to be tested as a tool for ‘broadening opportunities’ real time (immediate) or as short term monitoring by practitioners in their work environment.

Short term monitoring requires well-functioning sharp-end – blunt-end interaction to identify and report adaptations for further investigation, as demonstrated in case 2. Learning how unplanned and undocumented adaptations have prevented a negative event and what enabled it may allow fast-track learning. Whereas the investigator by a traditional incident report only is provided with information on what went wrong (and perhaps an indication of why), the investigator after a report including otherwise successful adaptations may be provided with information on what has worked to prevent a negative situation, together with perceived factors of what enables the success. To put the framework to practical and short term use, incident reporting schemes can be adapted to include the analysis categories and perspective of the framework (such as the cases described in this chapter). Further directions for framework development is to us it as a guide for after action review following events where adaptations outside formal procedure are necessary. For incident reporting and after action review sessions, practitioners must be trained to identify not only incidents or situations with a negative outcome, but also report situations of resilience such as where they have invented or relied on an un-planned or undocumented strategy.

Long term monitoring to identify patterns and reverberations of every-day adaptations can be supported by the framework, and relies on short term monitoring to gather relevant data for analysis. Long term monitoring and analysis of situation in the aftermath of the event allows the identification of trends in adaptive performance and their reverberations over time which can serve as a guide to assess system resilience and prediction of how future changes may affect the overall system’s abilities. However, the analyst must be cautious of hindsight bias, i.e. be careful not to assess the adaptation based on outcome, but examine what the circumstances, forces and enabling conditions are telling us about the system operations, its resilience and its brittleness. Similar to incident reporting, accident investigation can be enhanced and complemented by a resilience perspective using the framework as support. When an accident has occurred, information on how similar situations previously were successfully dealt with allows for better insight into ‘work as done’ rather than relying on ‘work as imagined’. Furthermore, the framework can be used to enhance risk analyses by recognising strategies as part of ‘work as done’ and including an analysis of identified adaptation reverberations. Thus, vulnerabilities created as part of adaptations can potentially be foreseen and conditions to minimise the vulnerabilities can be strengthened.

The integration of resilience terminology into current safety management can provide insights into essential enablers for successful adaptive performance that may not surface through traditional reporting mechanisms. Analysing sharp-end work not only as it goes wrong but also what enables it to go right offers new perspectives on how to improve safety and the ability to deal with unexpected and unforeseen events.

Commentary

In addition to the distinction between work-as-imagined and work-as-done, another important dichotomy is the difference between the sharp-end and the blunt-end. The two are furthermore not unrelated, since it often is the people at the blunt-end who prescribe how work should be done – but based on generalised knowledge rather than actual experience. Following the plea of Le Coze et al., this chapter presents a framework to analyse sharp-end adaptations in complex work settings. The analyses focus not only at what went wrong, but also looked at what actually happened: this focus on work-as-done brought forward experiences that would have been missed by traditional reporting approaches. By describing these using the four abilities (to respond, to monitor, to learn and to anticipate), the framework provides a window on how people deal successfully with unexpected and unforeseen events.