Bob Nardelli expected to win the three-way competition to succeed management legend Jack Welch as CEO of General Electric. He was stunned when Welch told him late in 2000 that he'd never run GE. The next day, though, he found out that he'd won the consolation prize. A director of Home Depot called to tell him, "You probably could not feel worse right now, but you've just been hit in the ass with a golden horseshoe" (Sellers, 2002, p. 1).

Within a week, Nardelli hired on as Home Depot's new CEO. He was a big change from the free-spirited founders, who had built the wildly successful retailer on the foundation of an uninhibited, entrepreneurial "orange" culture. Managers ran their stores using "tribal knowledge," and customers counted on friendly, knowledgeable staff for helpful advice. Nardelli revamped Home Depot with a heavy dose of command-and-control management, discipline, and metrics. Almost all the top executives and many of the frontline managers were replaced, often by ex-military hires. At first, it seemed to work—profits improved, and management experts hailed the "remarkable set of tools" Nardelli used to produce "deep, lasting culture change" (Charan, 2006, p. 1). But the lasting change included a steady decline in employee morale and customer service. Where the founders had successfully promoted "make love to the customers," Nardelli's toe-the-line stance pummeled Home Depot to last place in its industry for customer satisfaction.

A growing chorus of critics harped about everything from the declining stock price to Nardelli's extraordinary $245 million in compensation. At Home Depot's 2006 shareholders' meeting, Nardelli hoped to keep naysayers at bay by giving them little time to say anything and refusing to respond to anything they did say: "It was, as even Home Depot executives will concede, a 37-minute fiasco. In a basement hotel ballroom in Delaware, with the board nowhere in sight and huge time displays on stage to cut off angry investors, Home Depot held a hasty annual meeting last year that attendees alternately described as 'appalling' and 'arrogant' " (Barbaro, 2007, p. C1). The outcry from shareholders and the business press was scathing. Nardelli countered with metrics to show that all was well. He seemed unaware or unconcerned that he had embarrassed his board, enraged his shareholders, turned off his customers, and reinforced his reputation for arrogance and a tin ear. Nardelli abruptly left Home Depot at the beginning of 2007 (Grow, 2007).

Nardelli's old boss, Jack Welch, called him the best operations manager he'd ever seen. Yet, as talented and successful as he was, Nardelli flamed out at Home Depot because he was only seeing part of the picture. He was a victim of one of the most common afflictions of leaders: seeing an incomplete or distorted picture as a result of overlooking or misinterpreting important signals. An extensive literature on business blunders attests to the pervasiveness of this lost-at-sea state (see, for example, Adler and Houghton, 1997; Feinberg and Tarrant, 1995; Ricks, 1999; Sobel, 1999).

Enron's demise provides another example of floundering in a fog. In its heyday, Enron proclaimed itself the "World's Leading Company"—with some justification. Enron had been a perennial honoree on Fortune's list of "America's Most Admired Companies" and was ranked as the "most innovative" six years in a row (McLean, 2001, p. 60). Small wonder that CEO Kenneth W. Lay was among the nation's most admired and powerful business leaders. Lay and Enron were on a roll. What could be wrong with such a big, profitable, innovative, fast-growing company?

The trouble was that the books had been cooked, and the outside auditors were asleep at the switch. In December 2001, Enron collapsed in history's then-largest corporate bankruptcy. In the space of a year, its stock plunged from eighty dollars to eighty cents a share. Tens of billions of dollars in shareholder wealth evaporated. More than four thousand people lost their jobs and, in many cases, their savings and retirement funds.[1] The auditors also paid a steep price. Andersen Worldwide, a hundred-year-old firm with a once-sterling reputation, folded along with Enron.

What went wrong? After the cave-in, critics offered a profusion of plausible explanations. Yet Enron's leaders seemed shocked and baffled by the abrupt free fall. Former CEO Jeffrey K. Skilling, regarded as the primary architect of Enron's high-flying culture, was described by associates as "the ultimate control freak. The sort of hands-on corporate leader who kept his fingers on all the pieces of the puzzle" (Schwartz, 2002, p. C1). Skilling resigned for unexplained "personal reasons" only three months before Enron imploded. Many wondered if he had jumped ship because he foresaw the iceberg looming dead ahead. But after Enron's crash, he claimed, "I had no idea the company was in anything but excellent shape" (p. C1). Ultimately, in October 2006, both he and Lay were convicted of multiple counts of fraud for their role in Enron's disintegration. During their trials both steadfastly contended that they had done nothing wrong. Enron, they insisted, had been a sound and successful company brought down by forces they either weren't aware of or couldn't control. Despite public opinion to the contrary, both seemed to genuinely believe that they were victims rather than villains.

Skilling and Lay were both viewed as brilliant men, yet both sought refuge in cluelessness. It is easy to argue they claimed ignorance only because they had no better defense. Even so, they were out of touch at a deeper level. Lay and Skilling were passionate about building Enron into the "World' s Leading Company." They staunchly believed that they had created a mold-breaking company with a revolutionary business model. They knew risks were involved, but you have to bend or break old rules when you're exploring uncharted territory. Investors bought the stock, and business professors wrote articles about the management lessons behind Enron's success. The snare was that Lay and Skilling had misread their world and had no clue that they were destroying the company they loved.

The curse of cluelessness is not limited to corporations—government provides its share of examples. In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans. Levees failed, and much of the city was underwater. Tens of thousands of people, many poor and black, found themselves stranded for days in desperate circumstances. Government agencies bumbled aimlessly, and help was slow to arrive. As Americans watched television footage of the chaos, they were stunned to hear the nation's top disaster official, the secretary of Homeland Security, tell reporters that he "had no reports" of things viewers had seen with their own eyes. It seemed he might have been better informed if he had relied on CNN rather than his own agency.

Homeland Security, Enron, and Home Depot represent only a few examples of an endemic challenge: how to know if you're getting the right picture or tuning in to the wrong channel. Managers often fail this test. Cluelessness is a fact of life, even for very smart people. Sometimes, the information they need is fuzzy or hard to get. Other times, they ignore or misinterpret information at hand. Decision makers too often lock themselves into flawed ways of making sense of their circumstances. For Lay and Skilling, it was a mistaken view that "we're different from everyone else—we're smarter." For Nardelli, it was his conviction that his metrics gave him the full picture.

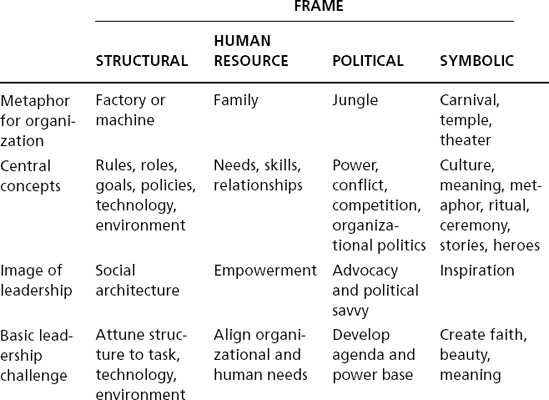

In the discussion that follows, we explore the origins and symptoms of cluelessness. We introduce reframing—the conceptual core of the book and our basic prescription for sizing things up. Reframing requires an ability to think about situations in more than one way. We then introduce four distinct frames— structural, human resource, political, and symbolic—each logical and powerful in its own right. Together, they help us decipher the full array of significant clues, capturing a more comprehensive picture of what's going on and what to do.

Before the emergence of the railroad and the telegraph in the mid-nineteenth century, individuals managed their own affairs—America had no multiunit businesses and no need for professional managers (Chandler, 1977). Explosive technological and social changes have produced a world that is far more interconnected, frantic, and complicated than it was in those days. Humans struggle to catch up, at continual risk of drowning in complexity that puts us "in over our heads" (Kegan, 1998). Forms of management and organization effective a few years ago are now obsolete. Sérieyx (1993) calls it the organizational big bang: "The information revolution, the globalization of economies, the proliferation of events that undermine all our certainties, the collapse of the grand ideologies, the arrival of the CNN society which transforms us into an immense, planetary village—all these shocks have overturned the rules of the game and suddenly turned yesterday' s organizations into antiques" (pp. 14–15).

The proliferation of complex organizations has made most human activities collective endeavors. We grow up in families and then start our own families. We work for business or government. We learn in schools and universities. We worship in synagogues, churches, and mosques. We play sports in teams, franchises, and leagues. We join clubs and associations. Many of us will grow old and die in hospitals or nursing homes. We build these human enterprises because of what they can do for us. They offer goods, entertainment, social services, health care, and almost everything else that we use, consume, or enjoy.

All too often, however, we experience a darker side. Organizations can frustrate and exploit people. Too often, products are flawed, families are dysfunctional, students fail to learn, patients get worse, and policies backfire. Work often has so little meaning that jobs offer nothing beyond a paycheck. If we can believe mission statements and public pronouncements, every company these days aims to nurture its employees and delight its customers. But many miss the mark. Schools are blamed for social ills, universities are said to close more minds than they open, and government is criticized for red tape and rigidity. The private sector has its own problems. Automakers drag their feet about recalling faulty cars. Producers of food and pharmaceuticals make people sick with tainted products. Software companies deliver bugs and "vaporware." Industrial accidents dump chemicals, oil, toxic gas, and radioactive materials into the air and water. Too often, corporate greed and insensitivity create havoc for individual lives and communities. The bottom line: we seem hard-pressed to manage organizations so that their virtues exceed their vices. The big question: Why?

The Curse of Cluelessness

Year after year, the best and brightest managers maneuver or meander their way to the apex of enterprises great and small. Then they do really dumb things. How do bright people turn out so dim? One theory is that they're too smart for their own good. Feinberg and Tarrant (1995) label it the "self-destructive intelligence syndrome." They argue that smart people act stupid because of personality flaws—things like pride, arrogance, and unconscious desires to fail. It's true that psychological flaws have been apparent in such brilliant, self-destructive individuals as Adolph Hitler, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton. But on the whole, intellectually challenged people have as many psychological problems as the best and brightest. The primary source of cluelessness is not personality or IQ. We're at sea whenever our sense-making efforts fail us. If our image of a situation is wrong, our actions will be wide of the mark as well. But if we don't realize our image is incorrect, we won't understand why we don't get what we hoped for. So, like Bob Nardelli, we insist we're right even when we're off track.

Vaughan (1995), in trying to unravel the causes of the 1986 disaster that destroyed the Challenger space shuttle and killed its crew, underscored how hard it is for people to surrender their entrenched mental models: "They puzzle over contradictory evidence, but usually succeed in pushing it aside—until they come across a piece of evidence too fascinating to ignore, too clear to misperceive, too painful to deny, which makes vivid still other signals they do not want to see, forcing them to alter and surrender the world-view they have so meticulously constructed" (p. 235).

All of us sometimes construct our own psychic prisons, and then lock ourselves in. When we don't know what to do, we do more of what we know. This helps explain a number of unsettling reports from the managerial front lines:

Hogan, Curphy, and Hogan (1994) estimate that the skills of one-half to three-quarters of American managers are inadequate for the demands of their jobs. But most probably don't realize it: Kruger and Dunning (1999) found that the more incompetent people are, the more they overestimate their performance, partly because they don't know what good performance looks like.

About half of the high-profile senior executives companies hire fail within two years, according to a 2006 study (Burns and Kiley, 2007).

In 2003, the United States was again the world's strongest economy, yet corporate America set a new record for failure with two of history's top three bankruptcies—WorldCom at $104 billion and Conseco at $61 billion. Charan and Useem (2002) trace such failures to a single source: "managerial error" (p. 52).

Small wonder that so many organizational veterans nod assent to Scott Adams's admittedly unscientific "Dilbert principle": "the most ineffective workers are systematically moved to the place where they can do the least damage— management" (1996, p. 14).

Strategies for Improving Organizations: The Track Record

We have certainly made an effort to improve organizations. Legions of managers report to work each day with that hope in mind. Authors and consultants spin out a flood of new answers and promising solutions. Policymakers develop laws and regulations to guide organizations on the right path.

The most common improvement strategy is upgrading management. Modern mythology promises that organizations will work splendidly if well managed. Managers are supposed to have the big picture and look out for their organization's overall health and productivity. Unfortunately, they have not always been equal to the task, even when armed with computers, information systems, flowcharts, quality programs, and a panoply of other tools and techniques. They go forth with this rational arsenal to try to tame our wild and primitive workplaces. Yet in the end, irrational forces too often prevail.

When managers cannot solve problems, they hire consultants. Today, the number and variety of advice givers is overwhelming. Most have a specialty: strategy, technology, quality, finance, marketing, mergers, human resource management, executive search, outplacement, coaching, organization development, and many more. For every managerial challenge, there is a consultant willing to offer assistance—at a price.

For all their sage advice and remarkable fees, consultants have yet to make a significant dent in problems plaguing organizations—businesses, public agencies, military services, hospitals, and schools. Sometimes the consultants are more hindrance than help, though they often lament clients' failure to implement their profound insights. McKinsey & Co., "the high priest of high-level consulting" (Byrne, 2002a, p. 66), worked so closely with Enron that managing partner Rajat Gupta sent his chief lawyer to Houston after Enron's collapse to see if his firm might be in legal trouble. The lawyer reported that McKinsey was safe, and a relieved Gupta insisted bravely, "We stand by all the work we did. Beyond that, we can only empathize with the trouble they are going through. It's a sad thing to see" (p. 68).

When managers and consultants fail, government frequently responds with legislation, policies, and regulations. Constituents badger elected officials to "do something" about a variety of ills: pollution, dangerous products, hazardous working conditions, and chaotic schools, to name a few. Governing bodies respond by making "policy." A sizable body of research records a continuing saga of perverse ways in which the implementation process distorts policymakers ' intentions (Bardach, 1977; Elmore, 1978; Freudenberg and Gramling, 1994; Peters, 1999; Pressman and Wildavsky, 1973). Policymakers, for example, have been trying for decades to reform U.S. public schools. Billions of taxpayer dollars have been spent. The result? About the same as America's switch to the metric system. In the 1950s Congress passed legislation mandating adoption of the metric standards and measures. To date, progress has been minimal (see Chapter Eighteen). If you know what a hectare is, or can visualize the size of a three-hundred-gram package of crackers, you're ahead of most Americans. Legislators did not factor into their solution what it would take to get their decision implemented.

In short, difficulties surrounding improvement strategies are well documented. Exemplary intentions produce more costs than benefits. Problems outlast solutions. It is as if tens of thousands of hard-working, highly motivated pioneers keep hacking at a swamp that persistently produces new growth faster than the old can be cleared. To be sure, there are reasons for optimism. Organizations have changed about as much in the past few decades as in the preceding century. To survive, they had to. Revolutionary changes in technology, the rise of the global economy, and shortened product life cycles have spawned a flurry of activity to design faster, more flexible organizational forms. New organizational models flourish in companies such as Pret à Manger (the socially conscious U.K. sandwich shops), Google (a hot American company), and Novo-Nordisk (a Danish pharmaceutical company that includes environmental and social metrics in its bottom line). The dispersed collection of enthusiasts and volunteers who provide content for Wikipedia and the far-flung network of software engineers who have developed the Linux operating system provide dramatic examples of possibilities in the digital world. But despite such successes, failures are still too common. The nagging key question: How can leaders and managers improve the odds for themselves as well for their organizations?

Goran Carstedt, the talented executive who led the turnaround of Volvo's French division in the 1980s, got to the heart of a challenge managers face every day: "The world simply can't be made sense of, facts can't be organized, unless you have a mental model to begin with. That theory does not have to be the right one, because you can alter it along the way as information comes in. But you can't begin to learn without some concept that gives you expectations or hypotheses" (Hampden-Turner, 1992, p. 167). Such mental models have many labels—maps, mind-sets, schema, and cognitive lenses, to name a few.[2] Following the work of Goffman, Dewey, and others, we have chosen the label frames. In describing frames, we deliberately mix metaphors, referring to them as windows, maps, tools, lenses, orientations, filters, prisms, and perspectives, because all these images capture part of the idea we want to convey.

A frame is a mental model—a set of ideas and assumptions—that you carry in your head to help you understand and negotiate a particular "territory." A good frame makes it easier to know what you are up against and, ultimately, what you can do about it. Frames are vital because organizations don't come with computerized navigation systems to guide you turn-by-turn to your destination. Instead, managers need to develop and carry accurate maps in their heads.

Such maps make it possible to register and assemble key bits of perceptual data into a coherent pattern—a picture of what's happening. When it works fluidly, the process takes the form of "rapid cognition," the process that Gladwell (2005) examines in his best-seller Blink. He describes it as a gift that makes it possible to read "deeply into the narrowest slivers of experience. In basketball, the player who can take in and comprehend all that is happening around him or her is said to have 'court sense' " (p. 44).

Dane and Pratt (2007) describe four key characteristics of this intuitive "blink" process:

It is nonconscious—you can do it without thinking about it and without knowing how you did it.

It is very fast—the process often occurs almost instantly.

It is holistic—you see a coherent, meaningful pattern.

It results in "affective judgments"—thought and feeling work together so you feel confident that you know what is going on and what needs to be done.

The essence of this process is matching situational clues with a well-learned mental framework—a "deeply-held, nonconscious category or pattern" (Dane and Pratt, 2007, p. 37). This is the key skill that Simon and Chase (1973) found in chess masters—they could instantly recognize more than fifty thousand configurations of a chessboard. This ability enables grand masters to play twenty-five lesser opponents simultaneously, beating all of them while spending only seconds on each move.

The same process of rapid cognition is at work in the diagnostic categories physicians rely on to evaluate patients' symptoms. The Hippocratic Oath— "Above all else, do no harm"—requires physicians to be confident that they know what they're up against before prescribing a remedy. Their skilled judgment draws on a repertoire of categories and clues, honed by training and experience. But sometimes they get it wrong. One source of error is anchoring: doctors, like leaders, sometimes lock on to the first answer that seems right, even if a few messy facts don't quite fit. "Your mind plays tricks on you because you see only the landmarks you expect to see and neglect those that should tell you that in fact you're still at sea" (Groopman, 2007, p. 65).

Treating individual patients is hard, but managers have an even tougher challenge because organizations are more complex and the diagnostic categories less well defined. That means that the quality of your judgments depends on the information you have at hand, your mental maps, and how well you have learned to use them. Good maps align with the terrain and provide enough detail to keep you on course. If you're trying to find your way around downtown San Francisco, a map of Chicago won't help, nor one of California's freeways. In the same way, different circumstances require different approaches.

Even with the right map, getting around will be slow and awkward if you have to stop and study at every intersection. The ultimate goal is fluid expertise, the sort of know-how that lets you think on the fly and navigate organizations as easily as you drive home on a familiar route. You can make decisions quickly and automatically because you know at a glance where you are and what you need to do next.

There is no shortcut to developing this kind of expertise. It takes effort, time, practice, and feedback. Some of the effort has to go into learning frames and the ideas behind them. Equally important is putting the ideas to use. Experience, one often hears, is the best teacher, but that is only true if you reflect on it and extract its lessons. McCall, Lombardo, and Morrison (1988, p. 122) found that a key quality among successful executives was an "extraordinary tenacity in extracting something worthwhile from their experience and in seeking experiences rich in opportunities for growth."

Frame Breaking

Framing involves matching mental maps to circumstances. Reframing requires another skill—the ability to break frames. Why do that? A news story from the summer of 2007 illustrates. Imagine yourself among a group of friends enjoying dinner on the patio of a Washington, D.C., home. An armed, hooded intruder suddenly appears and points a gun at the head of a fourteen-year-old guest. "Give me your money," he says, "or I'll start shooting." If you're at that table, what do you do? You could try to break frame. That's exactly what Cristina "Cha Cha" Rowan did.

"We were just finishing dinner," [she] told the man. "Why don't you have a glass of wine with us?"

The intruder had a sip of their Chateau Malescot St-Exupéry and said, "Damn, that's good wine."

The girl's father ... told the intruder to take the whole glass, and Rowan offered him the bottle.

The robber, with his hood down, took another sip and a bite of Camembert cheese. He put the gun in his sweatpants....

"I think I may have come to the wrong house," the intruder said before apologizing. "Can I get a hug?"

Rowan ... stood up and wrapped her arms around the would-be robber. The other guests followed.

"Can we have a group hug?" the man asked. The five adults complied.

The man walked away a few moments later with a filled crystal wine glass, but nothing was stolen, and no one was hurt. Police were called to the scene and found the empty wine glass unbroken on the ground in an alley behind the house [Associated Press, 2007].

In one stroke, Cha Cha Rowan redefined the situation from "we might all be killed" to "let's offer our guest some wine." Like her, artistic managers frame and reframe experience fluidly, sometimes with extraordinary results. A critic once commented to Cézanne, "That doesn't look anything like a sunset." Pondering his painting, Cézanne responded, "Then you don't see sunsets the way I do." Like Cézanne and Rowan, leaders have to find new ways to shift points of view when needed.

Like maps, frames are both windows on a territory and tools for navigation. Every tool has distinctive strengths and limitations. The right tool makes a job easier, but the wrong one gets in the way. Tools thus become useful only when a situation is sized up accurately. Furthermore, one or two tools may suffice for simple jobs, but not for more complex undertakings. Managers who master the hammer and expect all problems to behave like nails find life at work confusing and frustrating. The wise manager, like a skilled carpenter, wants at hand a diverse collection of high-quality implements. Experienced managers also understand the difference between possessing a tool and knowing when and how to use it. Only experience and practice bring the skill and wisdom to take stock of a situation and use suitable tools with confidence and skill.

The Four Frames

Only in the last half century have social scientists devoted much time or attention to developing ideas about how organizations work, how they should work, or why they often fail. In the social sciences, several major schools of thought have evolved. Each has its own concepts and assumptions, espousing a particular view of how to bring social collectives under control. Each tradition claims a scientific foundation. But a theory can easily become a theology that preaches a single, parochial scripture. Modern managers must sort through a cacophony of voices and visions for help.

Sifting through competing voices is one of our goals in writing this book. We are not searching for the one best way. Rather, we consolidate major schools of organizational thought into a comprehensive framework encompassing four perspectives. Our goal is usable knowledge. We have sought ideas powerful enough to capture the subtlety and complexity of life in organizations yet simple enough to be useful. Our distillation has drawn much from the social sciences—particularly sociology, psychology, political science, and anthropology. Thousands of managers and scores of organizations have helped us sift through social science research to identify ideas that work in practice. We have sorted insights from both research and practice into four major frames—structural, human resource, political, and symbolic (Bolman and Deal, 1984). Each is used by academics and practitioners alike and found on the shelves of libraries and bookstores.

Four Frames: As Near as Your Local Bookstore Imagine a harried executive browsing in the management section of her local bookseller on a brisk winter day in 2008. She worries about her company's flagging performance and fears that her job might soon disappear. She spots the black-on-white spine of The Last Link: Closing the Gap That Is Sabotaging Your Business (Crawford, 2007). Flipping through the pages, she notices chapter titles like "Data," "Discipline," and "Linking It Together." She is drawn to phrases such as "It all comes down to one thing, doesn't it. Are you making your numbers?" and "a new formula for 21st-century business success." "This stuff may be good," the executive tells herself, "but it seems a little stiff."

Next, she finds The SPEED of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything (Covey and Merrill, 2006). Glancing inside, she reads, "Take communication. In a high-trust relationship, you can say the wrong thing and people will still get your meaning. In a low-trust relationship, you can be very measured, even precise, and they'll still misinterpret you." "Sounds nice," she mumbles, "but a little touchy-feely. Let's look for something more down to earth."

Continuing her search, she picks up Secrets to Winning at Office Politics: How to Achieve Your Goals and Increase Your Influence at Work (McIntyre, 2005). She scans chapter titles: "Forget Fairness, Look for Leverage," "Political Games: Moves and Countermoves," "Power, Power, Who Has the Power?" She chews over the book's key message—that we all engage in politics every day at work, even though we don't like to admit it. "Does it really all come down to politics?" she wonders. "It seems too cynical. Isn't there something more uplifting?"

She spots The Starbucks Experience: 5 Principles for Turning Ordinary into Extraordinary (Michelli, 2006). She ponders the five basic principles the book credits for the success of Starbucks: Make it your own. Everything matters. Surprise and delight. Embrace resistance. Leave your mark. She reads that these principles "remind all of us—you, me, the janitor, and the CEO—that we are responsible for unleashing a passion that ripples outward from behind the scenes, through the customer experience, and ultimately out into our communities" (p. 1). She wonders if such fervor can be sustained for long.

In her local bookstore, our worried executive has rediscovered the four perspectives at the heart of this book. Four distinct metaphors capture the essence of each of the books she examined: organizations as factories, families, jungles, and temples or carnivals.

Factories The first book she stumbled on, The Last Link, provides counsel on how to think clearly and get organized, extending a long tradition that treats an organization as a factory. Drawing from sociology, economics, and management science, the structural frame depicts a rational world and emphasizes organizational architecture, including goals, structure, technology, specialized roles, coordination, and formal relationships. Structures—commonly depicted by organization charts—are designed to fit an organization's environment and technology. Organizations allocate responsibilities ("division of labor"). They then create rules, policies, procedures, systems, and hierarchies to coordinate diverse activities into a unified effort. Problems arise when structure doesn't line up well with current circumstances. At that point, some form of reorganization or redesign is needed to remedy the mismatch.

Families Our executive next encountered The SPEED of Trust, with its focus on interpersonal relationships. The human resource perspective, rooted in psychology, sees an organization as an extended family, made up of individuals with needs, feelings, prejudices, skills, and limitations. From a human resource view, the key challenge is to tailor organizations to individuals—finding ways for people to get the job done while feeling good about themselves and their work.

Jungles Secrets to Winning at Office Politics is a contemporary application of the political frame, rooted in the work of political scientists. It sees organizations as arenas, contests, or jungles. Parochial interests compete for power and scarce resources. Conflict is rampant because of enduring differences in needs, perspectives, and lifestyles among contending individuals and groups. Bargaining, negotiation, coercion, and compromise are a normal part of everyday life. Coalitions form around specific interests and change as issues come and go. Problems arise when power is concentrated in the wrong places or is so broadly dispersed that nothing gets done. Solutions arise from political skill and acumen—as Machiavelli suggested centuries ago in The Prince ([1514] 1961).

Temples and Carnivals Finally, our executive encountered The Starbucks Experience, with its emphasis on culture, symbols, and spirit as keys to organizational success. The symbolic lens, drawing on social and cultural anthropology, treats organizations as temples, tribes, theaters, or carnivals. It abandons assumptions of rationality prominent in other frames and depicts organizations as cultures, propelled by rituals, ceremonies, stories, heroes, and myths rather than rules, policies, and managerial authority. Organization is also theater: actors play their roles in the drama while audiences form impressions from what they see on stage. Problems arise when actors don't play their parts appropriately, symbols lose their meaning, or ceremonies and rituals lose their potency. We rekindle the expressive or spiritual side of organizations through the use of symbol, myth, and magic.

The FBI and the CIA: A Four-Frame Story

A saga of two squabbling agencies illustrates how the four frames provide different views of the same situation. Riebling (2002) documents the long history of head-butting between America's two intelligence agencies, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Central Intelligence Agency. Both are charged with combating espionage and terrorism, but the FBI's authority is valid within the United States, while the CIA's mandate covers everywhere else. Structurally, the FBI is housed in the Department of Justice and reports to the attorney general. The CIA reported through the director of central intelligence to the president until 2004, when a reorganization put it under a new director of national intelligence.

At a number of major junctures in American history (including the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the Iran-Contra scandal, and the 9/11 terrorist attacks), each agency held pieces of a larger puzzle, but coordination snafus made it hard for anyone to see all the pieces, much less put them together. After 9/11, both agencies came under heavy criticism, and each blamed the other for lapses. The FBI complained that the CIA had known, but had failed to inform the FBI, that two of the terrorists had entered the United States and had been living in California since 2000 (Seper, 2005). But an internal Justice Department investigation also concluded that the FBI didn't do very well with the information it did get. Key signals were never "documented by the bureau or placed in any system from which they could be retrieved by agents investigating terrorist threats" (Seper, 2005, p. 1).

Structural barriers between the FBI and the CIA were exacerbated by the enmity between the two agencies' patron saints, J. Edgar Hoover and "Wild Bill" Donovan. When he first became FBI director in the 1920s, Hoover reported to Donovan, who didn't trust him and tried to get him fired. When World War II broke out, Hoover lobbied to get the FBI identified as the nation's worldwide intelligence agency. He fumed when President Franklin D. Roosevelt instead created a new agency and made Donovan its director. As often happens, cooperation between two units was chronically hampered by a rocky personal relationship between two top dogs who never liked one another.

Politically, the relationship between the FBI and CIA was born in turf conflict because of Roosevelt's decision to give responsibility for foreign intelligence to Donovan instead of Hoover. The friction persisted over the decades as both agencies vied for turf and funding from Congress and the White House.

Symbolically, different histories and missions led to very distinct cultures. The FBI, which built its image with the dramatic capture or killing of notorious gang leaders, bank robbers, and foreign agents, liked to pounce on suspects quickly and publicly. The CIA preferred to work in the shadows, believing that patience and secrecy were vital to its task of collecting intelligence and rooting out foreign spies.

Senior U.S. officials have recognized for many years that the conflict between the FBI and CIA damages U.S. security. But most initiatives to improve the relationship have been partial and ephemeral, falling well short of addressing the full range of issues.

Multiframe Thinking

The overview of the four-frame model in Exhibit 1.1. shows that each of the frames has its own image of reality. You may be drawn to some and repelled by others. Some perspectives may seem clear and straightforward, while others seem puzzling. But learning to apply all four deepens your appreciation and understanding of organizations. Galileo discovered this when he devised the first telescope. Each lens he added contributed to a more accurate image of the heavens.

Successful managers take advantage of the same truth. Like physicians, they reframe, consciously or intuitively, until they understand the situation at hand. They use more than one lens to develop a diagnosis of what they are up against and how to move forward.

This claim about the advantages of multiple perspectives has stimulated a growing body of research. Dunford and Palmer (1995) found that management courses teaching multiple frames had significant positive effects over both the short and long term—in fact, 98 percent of their respondents rated reframing as helpful or very helpful, and about 90 percent felt it gave them a competitive advantage. Other studies have shown that the ability to use multiple frames is associated with greater effectiveness for managers and leaders (Bensimon, 1989, 1990; Birnbaum, 1992; Bolman and Deal, 1991, 1992a, 1992b; Heimovics, Herman, and Jurkiewicz Coughlin, 1993, 1995; Wimpelberg, 1987).

Multiframe thinking requires moving beyond narrow, mechanical approaches for understanding organizations. We cannot count the number of times managers have told us that they handled some problem the "only way" it could be done. Such statements betray a failure of both imagination and courage and reveal a paralyzing fear of uncertainty. It may be comforting to think that failure was unavoidable and we did all we could. But it can be liberating to realize there is always more than one way to respond to any problem or dilemma. Those who master reframing report a sense of choice and power. Managers are imprisoned only to the extent that their palette of ideas is impoverished.

Akira Kurosawa's classic film Rashomon recounts the same event through the eyes of several witnesses. Each tells a different story. Similarly, organizations are filled with people who have their own interpretations of what is and should be happening. Each version contains a glimmer of truth, but each is a product of the prejudices and blind spots of its maker. No single story is comprehensive enough to make an organization truly understandable or manageable. Effective managers need multiple tools, the skill to use each, and the wisdom to match frames to situations.[3]

Lack of imagination—Langer (1989) calls it "mindlessness"—is a major cause of the shortfall between the reach and the grasp of so many organizations—the empty chasm between noble aspirations and disappointing results. The gap is painfully acute in a world where organizations dominate so much of our lives. The commission appointed by President George W. Bush to investigate the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, concluded that the strikes "should not have come as a surprise" but did because the "most important failure was one of imagination." Taleb (2007) depicts events like the 9/11 attacks as "black swans"— novel events that are unexpected because we have never seen them before. If every swan we've observed is white, we expect the same in the future. But fateful, make-or-break events are more likely to be situations we've never experienced before. Imagination is our best chance for being ready when a black swan sails into view, and multiframe thinking is a powerful stimulus to the broad, creative mind-set imagination requires.

Engineering and Art

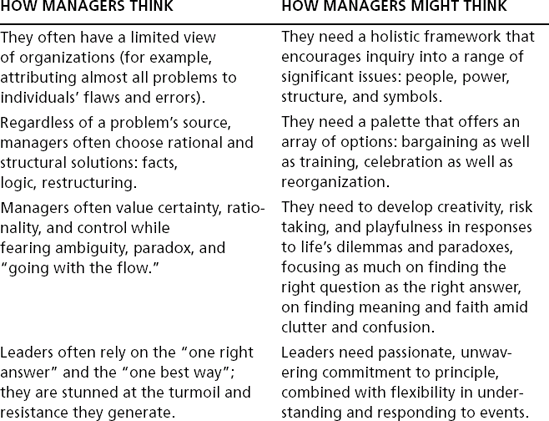

Exhibit 1.2 presents two contrasting approaches to management and leadership. One is a rational-technical mind-set emphasizing certainty and control. The other is an expressive, artistic conception encouraging flexibility, creativity, and interpretation. The first portrays managers as technicians; the second sees them as artists.

Artists interpret experience and express it in forms that can be felt, understood, and appreciated by others. Art embraces emotion, subtlety, ambiguity. An artist reframes the world so others can see new possibilities. Modern organizations often rely too much on engineering and too little on art in searching for quality, commitment, and creativity. Art is not a replacement for engineering but an enhancement. Artistic leaders and managers help us look beyond today's reality to new forms that release untapped individual energies and improve collective performance. The leader as artist relies on images as well as memos, poetry as well as policy, reflection as well as command, and reframing as well as refitting.

As organizations have become pervasive and dominant, they have also become harder to understand and manage. The result is that managers are often nearly as clueless as the Dilberts of the world think they are. The consequences of myopic management and leadership show up every day, sometimes in small and subtle ways, sometimes in organizational catastrophes. Our basic premise is that a primary cause of managerial failure is faulty thinking rooted in inadequate ideas. Managers and those who try to help them too often rely on constricted models that capture only part of organizational life.

Learning multiple perspectives, or frames, is a defense against thrashing around without a clue about what you are doing or why. Frames serve multiple functions. They are filters for sorting essence from trivia, maps that aid navigation, and tools for solving problems and getting things done. This book is organized around four frames rooted in both managerial wisdom and social science knowledge. The structural approach focuses on the architecture of organization— the design of units and subunits, rules and roles, goals and policies. The human resource lens emphasizes understanding people, their strengths and foibles, reason and emotion, desires and fears. The political view sees organizations as competitive arenas of scarce resources, competing interests, and struggles for power and advantage. Finally, the symbolic frame focuses on issues of meaning and faith. It puts ritual, ceremony, story, play, and culture at the heart of organizational life.

Each of the frames is both powerful and coherent. Collectively, they make it possible to reframe, looking at the same thing from multiple lenses or points of view. When the world seems hopelessly confusing and nothing is working, reframing is a powerful tool for gaining clarity, regaining balance, generating new options, and finding strategies that make a difference.

[1] Enron's reign as history's greatest corporate catastrophe was brief. An even bigger behemoth, WorldCom, with assets of more than $100 billion, thundered into Chapter 11 seven months later, in July 2002. Stock worth more than $45 a share two years earlier fell to nine cents.

[2] Among the possible ways of talking about frames are schemata or schema theory (Fiedler, 1982; Fiske and Dyer, 1985; Lord and Foti, 1986), representations (Frensch and Sternberg, 1991; Lesgold and Lajoie, 1991; Voss, Wolfe, Lawrence, and Engle, 1991), cognitive maps (Weick and Bougon, 1986), paradigms (Gregory, 1983; Kuhn, 1970), social categorizations (Cronshaw, 1987), implicit theories (Brief and Downey, 1983), mental models (Senge, 1990), definitions of the situation, and root metaphors.

[3] A number of scholars (including Allison, 1971; Bergquist, 1992; Birnbaum, 1988; Elmore, 1978; Morgan, 1986; Perrow, 1986; Quinn, 1988; Quinn, Faerman, Thompson, and McGrath, 1996; and Scott, 1981) have made similar arguments for multiframe approaches to groups and social collectives.