Life's daily challenges rarely arrive clearly labeled or neatly packaged. Instead, they immerse us in a murky, turbulent, and unrelenting flood. The art of reframing uses knowledge and intuition to make sense of the current and to find sensible and effective ways to channel the flow.

In this chapter, we illustrate the process by following a new principal through his first week in a deeply troubled urban high school.[13] Had this been a corporation in crisis, a struggling hospital, or an embattled public agency, the basic leadership issues would be much the same. We assume that our protagonist is familiar with the frames and with reframing and is committed to the view of leadership and ethics described in Chapter Nineteen. How might he use what he knows to figure out what's going on? What strategies can he mull over? What will he do?

Read the case thoughtfully. Ask yourself what you think is going on and what options you would consider. Then compare your reflections with his.

David King inherited a job that had broken his predecessor and could easily destroy him as well. His new staff greeted him with a jumble of problems, demands, maneuvers, and threats. His first staff meeting began with an undercurrent of tension and ended in outright hostility. Sooner or later, almost every manager will encounter situations this bad—or worse. The results are often devastating, leaving the manager feeling confused, overwhelmed, and helpless. Nothing makes any sense, and nothing seems to work. No good options are apparent. Can King escape such a dismal fate?

There is one potential bright spot. As the case ends, King is talking to Eleanor Debbs on a Saturday morning. She is a supportive colleague. He also has some slack—the rest of the weekend—to regroup. Where should he begin? We suggest that he might start by actively reflecting and reframing. A straightforward way to do that is to examine the situation one frame at a time asking two simple questions: From this perspective, what's going on? And what options does this angle suggest? This reflective process deserves ample time and careful thought. It requires "going to the balcony" (see Heifetz, 1994) to get a panoramic view of the scene below. Ideally, King would include one or more other people—a valued mentor, principals in other schools, close friends, his spouse—for alternative perceptions in pinpointing the problem and developing a course of action. We present a streamlined version of the kind of thinking that David King might entertain.

King sits down at his kitchen table with a cup of coffee, a pen, and a fresh yellow pad. He starts to review structural issues at Kennedy High. He recalls the "people-blaming" approach (Chapter Two), in which individuals are blamed for everything that goes wrong. He smiles and nods his head. That's it! Everyone at Kennedy High School is blaming everyone else. He recalls the lesson of the structural frame: we blame individuals when the real problems are systemic.

So what structural problems does Kennedy High have? King thinks about the two cornerstones of structure, differentiation and integration. In a flash of insight, he sees that Kennedy High School has an ample division of labor but weak overall coordination. He scribbles on his pad, trying to sketch the school's organization chart. He gradually realizes that the school has a matrix structure—teachers have an ill-defined dual reporting relationship to both department chairs and housemasters. He remembers the downside of the matrix structure: it's built for conflict (teachers wonder which authority they're supposed to answer to, and administrators bicker about who's in charge). The school has no integrating devices to link the approaches of housemasters like Chauncey Carver (who wants a coherent, effective program for his house) with those of department chairs like Betsy Dula (who is concerned about the schoolwide English curriculum and adherence to district guidelines). It's not just personalities; the structure is pushing Carver and Dula toward each other's throats. Goals, roles, and responsibilities are all vaguely defined. Nor is there a workable structural protocol (say, a task force or a standing committee) to diagnose and resolve such problems. If King had been in the job longer, he might have been able to rely more heavily on the authority of the principal's office. It helps that he's been authorized by the superintendent to fix the school. But so far, he's seen little evidence that the Kennedy High staff is endorsing his say-so with much enthusiasm.

King's musings are making sense, but it isn't clear what to do about the structural gaps. Is there any way to get the school back under control based on reason when it is teetering on the edge of irrational chaos? It doesn't help that his authority is shaky. He is having trouble controlling the staff, and they are having the same problem with the students. The school is an underbounded system screaming for structure and boundaries.

King notes, ruefully, that he made things worse in the Friday meeting. "I knew how these people felt about one another," he thinks. "Why did I push them to talk about something they were trying to avoid? We hadn't done any homework. I didn't give them a clear purpose for the conversation. I didn't set any ground rules for how to talk about the issue. When it started to heat up, I just watched. Why didn't I step in before it exploded?" He stops and shakes his head. "Live and learn, I guess. But I learned these lessons a long time ago—they served me well in turning the middle school around. In all the confusion, I forgot that even good people can't function very well without some structure. What did I do the last time around?"

King begins to brainstorm options. One possibility is responsibility charting (Chapter Five): bring people together to define tasks and responsibilities. It has worked before. Would it work here? He reviews the language of responsibility charting. The acronym CAIRO helps him remember. Who's responsible? Who has to approve? Who needs to be consulted? Who should be informed? Who doesn't need to be in the loop? As he applies these questions to Kennedy High, the overlap between the housemasters and the department chairs is an obvious problem. Without a clear definition of roles and relationships, conflict and confusion are inevitable. He wonders about a total overhaul of the structure: "Is the house system viable in its current form? If not, is it fixable? Maybe we need a process to look at the structure: What if I chaired a small task force to examine it and develop recommendations? I could put Dula and Carver on it—let them see firsthand what's causing their conflict. Get them involved in working out a new design. Give each authority over specific areas. Develop some policies and procedures."

It is clear even from a few minutes' reflection that Kennedy High School has major structural problems that have to be addressed. But what to do about the immediate crisis between Dula and Carver? The structure helped create the problem in the first place, and fixing it might prevent stuff like this in the future. But Dula's demand for an immediate apology didn't sound like something a rational approach would easily fix. King is ready to try another angle. He turns to the human resource frame for counsel.

"How ironic," King muses. "The original idea behind the school was to respond better to students. Break down the big, bureaucratic high school. Make the house a community, a family even, where people know and care about each other. But it's drifted off course. Everyone's marooned on the bottom of Maslow's needs hierarchy: no one even feels safe. Until they do, they'll never focus on caring. The problem isn't personalities. Everyone's frustrated because no one is getting needs met. Not me, not Carver, not Dula. We're all so needy, we don't realize everyone else is in the same boat."

King shifts his thoughts from individual needs to interpersonal relationships. It's hard not to turn that way, with the Dula-Carver mess staring him in the face. Tense relationships everywhere. People talking only to people who agree with them. Why? How to get a handle on it? He remembers reading, "Lurking in Model I is the core assumption that an organization is a dangerous place where you have to look out for yourself or someone else will do you in" (Chapter Eight). "That's it!" he says. "That's us. Too bad they don't give a prize for the most Model I school in America. We'd win hands down. Everything here is win-lose. Nothing is discussed openly, and if it is, people just attack each other. If anything goes wrong, we blame others and try to straighten them out. They get defensive, which proves we were right. But we never test our assumptions. We don't ask questions. We just harbor suspicions and wait for people to prove us right. Then we hit them over the head. We've got to find better ways to deal with one another.

"How do you get better people management?" King wonders. "Successful organizations start with a clear human resource philosophy. We don't have one, but it might help. Invest in people? We've got good people. They're paid pretty well. They've got job security. We're probably OK there. Job enrichment? Jobs here are plenty challenging. Empowerment? That's a big problem. Everyone claims to be powerless, yet somehow everyone expects me to fix everything. Is there something we could do to get people's participation? Get them to own more of the problem? Convince them we've got to work together to make things better? The trouble is, if we go that way, people probably don't have the group skills they'd need. Staff development? With all the conflict, mediation skills might be a place to start." Conflict. Politics. Politics is normal in an organization. He's read it, and he knows it's true. "But we don't seem to have a midpoint between getting along and getting even."

King reluctantly shifts to a political lens. It isn't easy for him. He knows it's relevant; but he doesn't like to play the political game. Still, he's never seen a school with more intense political strife. His old school is beginning to seem tame by comparison; he tackled some things head-on there. Kennedy is a lot more volatile, with a history of explosions. Coercive force seems to be the power tactic of choice. But that's not an option he's comfortable with.

Things might get even more vicious if he tackles the conflict openly. He mulls over the basic elements of the political frame: enduring differences, scarce resources, conflict, and power. "Bingo! We've got 'em all—in spades. We've got factions for and against the house concept. Housemasters want to run their houses and guard their turf. Department chairs want to run the faculty and expand their territory. One group wants to close the doors and bring in guards to keep outsiders away. Another wants to keep out the guards and throw open the doors. We've got race issues simmering under the surface. No Latino administrators. This Carver-Dula thing could blow up the school. Black male says he'll break white female's neck. A recipe for disaster. We need some damage control.

"Then we've got all those outside folks looking over our shoulder. Parents worry about safety. The school board doesn't trust us. All they care about is test scores. The media are looking for a story. Accreditation is coming in the spring. Maybe there's some way to get people thinking about the enemies outside instead of inside. A common devil might pull people together—for a little while anyway.

"Scarce resources? They're getting scarcer. We lost 10 percent of our teachers—that got us into the flexible staffing mess. Housemasters and department chairs are fighting over turf. Bill Smith wants my job. It's a war zone. We need some kind of peace settlement. But who's going to take the diplomatic lead? We don't seem to have any neutral parties. Eleanor Debbs would respond to the call. People respect her. But she's not an administrator."

King's attention turns to the two faces of power. "Power can be used to do people in. That's what we're doing right now. But you can also use power to get things done. That's the constructive side of politics. Too bad no one here seems to have a clue about it. If I'm going to be a constructive politician, what can I do? First, I need an agenda. Without that, I'm dead in the water. Basically, I want everyone working in tandem to make the school better for kids. Most people could rally behind that. I also need a strategy. Networking—I need good relationships with key folks like Smith, Carver, and Dula. The interviews were a good place to start. I learned a lot about who wants what. The Friday meeting was a mistake, a collision of special interests with no common ground. It's going to take some horse trading. We need a deal the housemasters and the department chairs can both buy into. And I need some allies—badly."

He smiles as he remembers all the times he's railed against analysis paralysis. But he feels he's getting somewhere. He turns to a clean sheet on his pad. "Let's lay this thing out," he says to the quiet, empty kitchen. Across the top he labels three columns: allies, fence-sitters, and opponents. At the top left, he writes" High power. "At the bottom left," Low power. "Over the next half-hour, he creates a political map of Kennedy High School, arranging individuals and groups in terms of their interests and their power. When he finishes, he winces. Too many powerful opponents. Too few supportive allies. A bunch of people waiting to choose sides. He begins to think about how to build a coalition and reshape the school's political map.

"No doubt about it," King says, "I have to get on top of the political mess. Otherwise they'll carry me out the same way they did Weis. But it's a little depressing. Where's the ray of hope?" He smiles. He's ready to think about symbols and culture. "Where's Dr. King when I need him?" He recalls the famous words from 1963: "For even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream." What happened to Kennedy High's dream?

He decides to take a break, get some fresh air. He takes stock of his surroundings. Moonlit night. Crowded sidewalks. Young and old, poor and affluent, black, white, and Latino. Merchandise pours out of stores into sidewalk bins: clothes, toys, electronic gear, fruit, vegetables—you name it. It makes him feel better. King runs into some students from his old school. They're at Kennedy now. "We're tellin' our friends we got a good principal now," they say. He thanks them, hoping they' re right.

Back to the kitchen and the yellow pad. Buoyed by the walk and another cup of coffee, he reviews the school' s history. "Interesting," he observes. "That's one of the problems: the school's too new to have many roots or traditions. What we have is mostly bad. We've got a hodgepodge of individual histories people brought from someplace else. Deep down, everyone is telling a different story. Maybe that's why Carver is so attached to his house and Dula to her English department. There's nothing schoolwide for people to bond to. Just little pockets of meaning."

He starts to think about symbols that might create common ground. Robert Kennedy, the school's namesake. He has only vague recollection of Bobby Kennedy's speeches. Anything there? He remembers the man. What was he like? What did he stand for? What were the founders thinking when they chose his name for the school? What signals were they trying to send? Any unifying theme? Then it comes to him—words from Bobby Kennedy's eulogy for his brother: "Some people see things as they are, and say why? I dream things that never were, and say why not?"

"That's the kind of thinking we need here," King realizes. "We need to get above all the factions and divisions. We need a banner or icon that we all can rally around. Celebrate Kennedy's legacy now? Can we have a ceremony in the midst of warring chaos? It could backfire, make things worse. But it seems the school never had any special occasions—even at the start. No rituals, no traditions. The only stories are downbeat ones. The high road might work. We've got to get back to the values that launched the school in the first place. Rekindle the spark. What if I pull some people together? Start from scratch—this time paying more attention to symbols and ceremony? We need some glue to weld this thing together."

Meaning. Faith. He rolls the words around in his mind. Haunting images. Ideas start to tumble out. "We're supposed to be pioneers, but somehow we got lost. A lighthouse where the bulb burned out. Not a beacon anymore. We're on the rocks ourselves. A dream became a nightmare. People's faith is pretty shaky. There's a schism—folks splitting into two different faiths. Like a holy war between the church of the one true house system and the temple of academic excellence. We need something to pull both sides together. Why did people join up in the first place? How can we get them to sign up again—renew their vows? "He smiles at the religious overtones in his thoughts. His mother and father would be proud.

He catches himself. "We're not a church; we're a school, in a country that separates religion and state. But maybe the symbolic concept bridges the gap. Organization as temple. A lot of it is about meaning. What's Kennedy High School really about? Who are we? What happened to our spirit? What's our soul, our values? That's what folks are fighting over! Deep down, we're split over two versions of what we stand for. Department chairs promoting excellence. Housemasters pushing for caring. We need both. That was the original dream. Bring excellence and caring together. We'll never get either if we're always at war with one another."

He thinks about why he got into public education in the first place. It was his calling. Why? Growing up in a racist society was tough, but his father had it a lot tougher—he was a principal when it was something black men didn't do. King had always admired his dad's courage and discipline. More than anything, he remembered his father's passion about education. The man was a real champion for kids—high standards, deep compassion. Growing up with this man as a role model, there was never much question in King's mind. As far back as he could remember, he'd wanted to be a principal too. It was a way to give to the community and to help young people who really needed it. To give everyone a chance. In the midst of a firefight, it was easy to forget his mission. It felt good to remember.

Before going further, King senses that it is a good time for a review. Over yet another cup of coffee, he goes back over his notes. They strike him as stream of consciousness, with some good stuff and a little whining and self-pity. He smiles as he remembers himself in graduate school, fighting against all that theory. "Don't think; do! Be a leader!" Now, here he is, thinking, reflecting, struggling to pull things together. In a strange way, it feels natural.

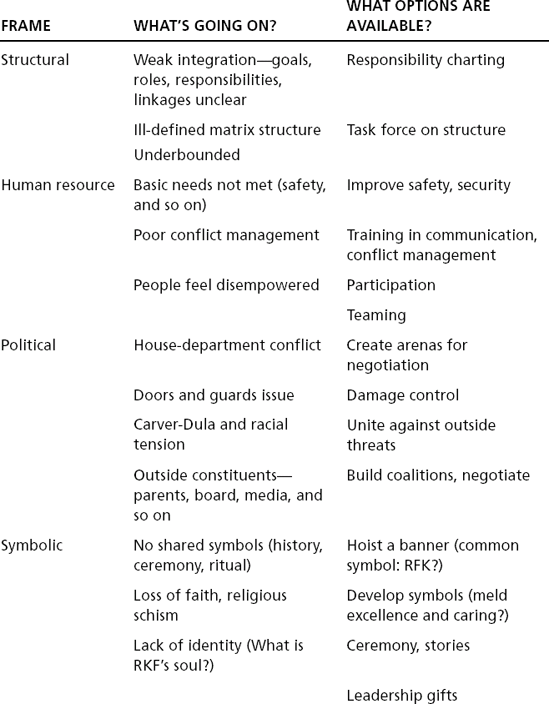

He organizes his ideas into a chart (see Exhibit 20.1). He's starting to feel better now. The picture is coming into focus. He feels he has a better sense of what he's up against. It's reassuring to see he has options. There are plenty of pitfalls, but some real possibilities. He knows he can't do everything at once; he needs to set priorities. He needs a plan of action, an agenda anchored in basic values. Where to begin? Soul? Values? He has to find a rallying point somewhere.

He has already embraced two values: excellence and caring. He turns his attention to leadership as gift giving. "I've mostly been waiting for others to initiate. What about me? What are my gifts? If I want excellence, the gift I have to offer is authorship. That's what people want. They don't want to be told what to do. They want to put their signature on this place. Make a contribution. They're fighting so hard because they care so much. That's what brought them to Kennedy in the first place. They wanted to be a part of something better. Create something special. They all want to do a good job. How can I help them do it without tripping over or maiming each other?

"What about caring? The leadership gift is love. No one's getting much of that around here." (He smiles as a song fragment comes to mind: "Looking for love in all the wrong places.") "I've been waiting for someone else to show caring and compassion, "he realizes." I've been holding back."

The thought leads him to pick up the phone. He calls Betsy Dula. She is out, but he leaves a message on the machine: "Betsy, Dave King. I've been thinking a lot about our conversation. One thing I want you to know is that I'm glad you're part of the Kennedy High team. You bring a lot, and I sure hope I can count on your help. We can't do it without you. We need to finish what we started out to do. I care. I know you do, too. I'll see you Monday."

He senses he's on a roll. But it's one thing to leave a message on someone's machine and another to deliver it in person—particularly if you don't know how receptive the other person will be. She may think I'm just shining on, faking it.

On his next call, to Chauncey Carver, King takes a deep breath. He gets through immediately. "Chauncey? Dave King. Sorry to bother you at home, but Betsy Dula called me this morning. She's upset about what you said yesterday. Particularly the part about breaking her neck."

King listens patiently as Carver makes it clear that he was only defending himself against Dula's unprovoked and inappropriate public attack. "Chauncey, I hear you.... Yeah, I know you're mad. So is she." King listens patiently through another one-sided tirade. "Yes, Chauncey, I understand. But look, you're a key to making this school work. I know how much you care about your house and the school. The word on the street is clear—you're a terrific housemaster. You know it, too. I need your help, man. If this thing with Betsy blows up and goes public, what's it going to do to the school? ... You're right, we don't need it. Think about it. Betsy's pushing hard for an apology."

He feared that the word apology might set Carver off again, and it does. This is getting tough. He reminds himself why he made the call. He shifts back into listening mode. After several minutes of venting, Chauncey pauses. Softly, King tries to make his point. "Chauncey, I'm not telling you what to do. I'm just asking you to think about it. I don't know the answer. Two heads might be better than one. Let me know what you come up with. Can we meet first thing Monday? ... Thanks for your time. Have a good weekend."

King puts down the phone. Things are still tense, but he hopes he's made a start. Carver is a loose cannon with a short fuse. But he's also smart, and he cares about the school. Get him thinking, King figures, and he'll see the risks in his comment to Dula. Push him too hard, and he'll fight like a cornered badger. With some space; he might just figure out something on his own. The gift of authorship. Would Chauncey bite? Or would the problem wind up back on the principal's doorstep—with prejudice?

After the conversation with Chauncey, King needs another breather. He goes back to his yellow pad, which has become something of a security blanket. More than that, it's helping him find his way to the balcony. It has given him a better view of the situation. He's made notes about excellence and caring. Is he making progress or just musing? It doesn't matter. He feels better; the situation seems to be getting clearer and his options more promising.

King's thoughts move on to justice. "Do people feel the school is fair?" he asks. "I'm not hearing a lot of complaints about injustice. But it wouldn't take much to set off another war. The Chauncey-Betsy thing is scary. A man physically threatening a woman could send a terrible message. There's too much male violence in the community already. Make it a black man and a white woman, and it gets worse. The fact that Chauncey and I are black men is good and bad: it makes for a better chance of getting Chauncey's help—brothers united and all that. But it could be devastating if people think I'm siding with Chauncey against Betsy—sisters in defiance. It's like being on a tightrope: one false step and I'm history. And the school too. All the more reason to encourage Chauncey and Betsy to work this out. If I could get the two together, what a symbol of unity that would be! Maybe just what we need. A positive step at least."

Finally, King thinks about the ethic of faith and the gift of significance. Symbols again, revisited in a deeper way. "How did Kennedy High go from high hopes to no hope in two years? How do we rekindle the original faith? How do we recapture the dream that launched the school? Well," he sighs, "I've been around this track before. My last school was a snake pit when I got there. Not as bad as Kennedy, but still pretty awful. We turned that one around, and I learned some things in the process—including being patient, while hanging tough. It's gonna be hard. But maybe fun, too. And it will happen. That's why I took this job in the first place. So what am I moaning about? I knew what I was getting into. It's just that knowing it in my head is one thing. Feeling it in my gut is another."

By Sunday night, King has twenty-five pages of notes. They help—but not as much as his conversation with himself in an empty kitchen. Going to the gallery, getting a fresh look, reflecting instead of just fretting. The inner dialogue has led to new conversations with others, on a deeper level. He's made a lot of phone calls, talked to almost every administrator in the building. A lot of them have been surprised—a principal who calls on the weekend is unusual.

He is making headway. He needs to hear from Betsy but has some volunteers for a task force on structural issues. He's done some relationship building. A second call to Chauncey to commend him for devotion to the mission. A deeper connection. Crediting Frank Czepak for excellent counsel, even if the principal isn't smart enough to pay attention—a frank admission.

Some has been pure politics. Negotiating a deal with Bill Smith: "I could help you, Bill, next time the district needs a principal, but only if you help me. You scratch my back, I'll scratch yours." Gently persuading Burt Perkins that his calling was scheduling, not running a house, and that moving to assistant principal would be a step up. A call to Dave Crimmins to tell him Perkins has decided to make a change. An encouraging conversation with Luz Hernandez, a stalwart in his previous school. She is at least willing to think about coming to Kennedy High as a housemaster. Planting seeds with everyone about ways to resolve the door problem.

Above all, King has worked on creating symbolic glue, renewing the hopes and dreams people felt at the time the school was founded. A cohesive group pulling together for a common purpose, a school everyone can feel proud of. His to-do list is ambitious. But at least he has one. A month and a half until the first day of school and a lot to accomplish. He isn't sure what the future will bring, but he feels a little more hope in the air. The knot in his stomach is mostly gone. So are the images of being carried off like his predecessor, a broken man with a shattered career.

The phone rings. It's Betsy Dula. She's been away for the weekend but wants to thank King for his message. It was important to know he cared, she told him. "By the way," she says, "Chauncey Carver called me. Said he felt bad about Friday. Told me he'd lost his temper and said some things he didn't really mean. He invited me to breakfast tomorrow."

"Are you going?" King asks, as nonchalantly as possible. He holds his breath, thinking, If she declines, we could be back to square one.

"Yes," she says. "Even a phone call is a big step for Chauncey. He's a proud and stubborn man. But we're both professionals. It's worth a try."

A sigh of relief. "One more question," King says. "When you came to the school, you knew it wouldn't be easy. Why did you sign up for this in the first place?"

She is silent for a long time. He can almost hear her thinking. "I love English and I love kids," she says. "And I want kids to love English."

"And now?" he asks.

"Can't we get past all the bickering and fighting? That's not why we launched this noble experiment. Let's get back to why we're here. Work together to make this a good school for our kids. They really need us."

"How about a great school we can all be proud of?" he asks.

"Sounds even better," she says. Maybe she doesn't grasp what he means. But they are beginning to read from the same page. It will take time, but they can work it out.

At the end of a very busy weekend, David King is still a long way from solving all the problems of Kennedy High. "But," he tells himself, "I made it through the valley of confusion and I'm feeling more like my old self. The picture of what I'm up against is a lot clearer. I'm seeing a lot more possibilities than I was seeing on Friday. In fact, I've got some exciting things to try. Some may work; some may not. But deep down, I think I know what's going on. And I know which way is west. We're now moving roughly in that direction."

He can't wait for Monday morning.

A different David King would probably raise other questions and see other options. Reframing, like management and leadership, is more art than science. Every artist brings a distinctive vision and produces unique works. King's reframing process necessarily builds on a lifetime of skill, knowledge, intuition, and wisdom. Reframing guides him in accessing what he already knows. It helps him feel less confused and overwhelmed by the doubt and disorder around him. A cluttered jumble of impressions and experiences gradually evolves into a manageable image. His reflections help him see that he is far from helpless—he has a rich array of actions to choose from. He has also rediscovered a very old truth: reflection is a spiritual discipline, much like meditation or prayer. A path to faith and heart. He knows the road ahead is still long and difficult. There is no guarantee of success. But he feels more confident and more energized than when he started. He is starting to dream things that never were and say, "Why not?"

[13] The case in this chapter was adapted from case no. 9-474-183, Robert F. Kennedy High School, ©1974 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission of the Harvard Business School. The case was prepared by John J. Gabarro as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate the effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.