No one could have forecast what New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani would face on September 11, 2001. During a breakfast meeting, he learned that a plane had hit one of the World Trade Center's twin towers. He went directly to the scene, arriving in time to see the devastating strike on the second tower. It was now clear that this was planned terrorism, an unprecedented human tragedy and a deep symbolic wound for the city.

In the aftermath, the American public observed what many assumed was a transformed Giuliani—a sensitive, emotional, and deeply caring leader whose ubiquitous presence was a source of inspiration to New Yorkers, as well as to all Americans. But His Honor disputes his supposed personal makeover: "The events of September 11 affected me more deeply than anything I have ever experienced; but the idea that I somehow became a different person on that day— that there was a pre—September 11 Rudy and a wholly other post-September Rudy—is not true. I was prepared to handle September 11 precisely because I was the same person who had been doing his best to take on challenges my whole career .... You can't be paralyzed by any situation. It's about balance" (Giuliani and Kurson, 2002, pp. x, xiii).

In an unprecedented crisis, Giuliani found himself drawing upon different aspects of his cognitive and behavioral repertoire—lessons learned from prior experience. Both the mayor and his constituents faced dramatically altered circumstances, which required new thinking and realignment of their perceptive lenses. Symbolism, for example, had always seemed prominent in Giuliani's leadership but became even more so after 9/11. Meanwhile, the political dynamics on which Giuliani had historically thrived receded in relative significance.

Harmonizing the frames, and crafting inventive responses to new circumstances, is essential to both management and leadership. This chapter considers the frames in combination. How do you choose a way to frame an event? How do you integrate multiple lenses in the same situation? We begin by revisiting the turbulent world of managers. We then explore what happens when people rely on different views of the same challenge. We offer questions and guidelines to stimulate thinking about which prisms are likely to apply in specific situations. Finally, we examine literature on effective managers and organizations to see which modes of thought dominate current theory.

Prevailing mythology depicts managers as rational men and women who plan, organize, coordinate, and control activities of subordinates. Periodicals, books, and business schools paint a pristine image of modern managers: unruffled and well organized, with clean desks, power suits, and sophisticated information systems. Such "super managers" develop and implement farsighted strategies, producing predictable and robust results. It is a reassuring picture of clarity and order. Unfortunately, it's wrong.

An entirely different picture appears if you watch managers at work (Carlson, 1951; Kotter, 1982; Mintzberg, 1973; Luthans, 1988). It's a hectic life, shifting rapidly from one situation to another. Decisions emerge from a fluid, swirling vortex of conversations, meetings, and memos. Information systems ensure an overload of detail about what happened last month or last year. Yet they fail to answer a far more important question: What to do next? In Afghanistan, sophisticated systems make information from battle zones readily available all the way up the command structure. But a faster flow of information has slowed rather than sped up tactical decision making because top officers can now ponder decisions better made on the spot. After identifying a high-value target, Special Forces may wait days before receiving permission to fire. By then the target is long gone.

In deciding what to do next, managers operate largely on the basis of intuition, drawing on firsthand observations, hunches, and judgment derived from experience. Too swamped to spend much time thinking, analyzing, or reading, they get most of their information in meetings, through e-mail, or over the phone. They are hassled priests, modern muddlers, and corporate wheeler-dealers.

How does one reconcile the actual work of managers with the heroic imagery? "Whenever I report this frenetic pattern to groups of executives," says Harold Leavitt, "regardless of hierarchical level or nationality, they always respond with a mix of discomfiture and recognition. Reluctantly, and somewhat sheepishly, they will admit that the description fits, but they don't like to be told about it. If they were really good managers, they seem to feel, they would be in control, their desks would be clean, and their shops would run as smoothly as a Mercedes engine" (1996, p. 294). Led to believe that they should be rational and on top of things, managers may instead become bewildered and demoralized. They are supposed to plan and organize, yet they find themselves muddling around and playing catch-up. They want to solve problems and make decisions. But when problems are ill defined and options murky, control is an illusion and rationality an afterthought.

Life in organizations is packed with happenings that can be interpreted in a number of ways. Exhibit 15.1 examines familiar processes through four lenses. As the chart shows, any event can be framed in several ways and serve multiple purposes. Planning, for example, produces specific objectives. But it also creates arenas for airing conflict and becomes a sacred occasion to renegotiate symbolic meanings.

Multiple realities produce confusion and conflict as individuals look at the same event through different lenses. A hospital administrator once called a meeting to make an important decision. The chief technician viewed it as a chance to express feelings and build relationships. The director of nursing hoped to gain power vis-à-vis physicians. The medical director saw it as an occasion for reaffirming the hospital's distinctive approach to medical care. The meeting became a cacophonous jumble, like a group of musicians each playing from a different score.

The confusion that can result when people view the world through different lenses is illustrated in this classic case:

In a given situation, one cognitive map may be more helpful than others. At a strategic crossroads, a rational process focused on gathering and analyzing information may be exactly what is needed. At other times, developing commitment or building a power base may be more critical. In times of great stress, decision processes may become a form of ritual that brings comfort and support. Choosing a frame to size things up, or understanding others' perspectives, involves a combination of analysis, intuition, and artistry. Exhibit 15.2 poses questions to facilitate analysis and stimulate intuition. It also suggests conditions under which each way of thinking is most likely to be effective.

Are commitment and motivation essential to success? The human resource and symbolic approaches need to be considered whenever issues of individual dedication, energy, and skill are vital to success. A new curriculum launched by a school district will fail without teacher support. Support might be strengthened by human resource approaches, such as participation and self-managing teams, or through symbolic approaches linking the innovation to values and symbols teachers cherish.

Is the technical quality important? When a good decision needs to be technically sound, the structural frame's emphasis on data and logic is essential. But if a decision must be acceptable to major constituents, then human resource, political, or symbolic issues loom larger. Could the technical quality of a decision ever be unimportant? A college found itself embroiled in a three-month battle over the choice of a commencement speaker. The faculty pushed for a great scholar, the students for a movie star. The president was more than willing to invite anyone acceptable to both groups; she saw no technical criterion proving that one choice was better than the other.

Are ambiguity and uncertainty high? If goals are clear, technology is well understood, and behavior is reasonably predictable, the structural and human resource approaches are likely to apply. As ambiguity increases, the political and symbolic perspectives become more relevant. The political frame expects that the pursuit of self-interest will often produce confused and chaotic contests that require political intervention. The symbolic lens sees symbols as a way of finding order, meaning, and "truth" in situations too complex, uncertain, or mysterious for rational or political analysis. In the R. J. Reynolds leveraged buyout (discussed in Chapter Eleven), the most critical unknown was what opposing bidders were doing and what it meant. Everyone scouted the competition intensely and tried to interpret and read meaning into even the weakest signals. At a key point in the endgame, Henry Kravis hinted that he might drop out. To make the hint credible, he went off for a long weekend in Colorado just before final bids were due. The opposition picked up the signals and concluded, "Henry's not bidding." It was, according to one member of the other team, "our fatal error."

Are conflict and scarce resources significant? Human resource logic fits best in situations favoring collaboration—as in profitable, growing firms or highly unified schools. But when conflict is high and resources are scarce, dynamics of conflict, power, and self-interest regularly come to the fore. In situations like the Reynolds bidding war, sophisticated political strategies are vital to success. In other cases, skilled leaders may find that an overarching symbol helps potential adversaries transcend their differences and work together. In the early 1980s, Yale University was paralyzed by a clerical and technical workers' strike. No one, including Yale's president, A. Bartlett Giamatti, knew how to settle the dispute. Then Phil Donahue invited the Yale community to appear on his television show. Union members energetically presented their side, and Giamatti represented the administration. The audience was active and vocal but polarized. Near the end of the program, Giamatti told a story about his father, an Italian immigrant, who was admitted to the neighborhood university, which happened to be Yale. His father couldn't pay the tuition, but Yale had a core value of "admission by ability, support by need." The story and the invocation of a shared value helped bridge the chasm dividing the parties.

Are you working from the bottom up? Restructuring is an option primarily for those in a position of authority. Human resource approaches to improvement— such as training, job enrichment, and participation—usually need support from the top to be successful. The political frame, in contrast, fits well for changes initiated from below. Because partisans—change agents lower in the pecking order—rarely can rely on formal clout, they must find other bases of power, such as symbolic acts to draw attention to their cause and embarrass opponents. The 9/11 terrorists could have picked from an almost unlimited array of targets, but the World Trade Towers and the Pentagon were deliberately selected for their symbolic value.

The questions in Exhibit 15.2 are no substitute for judgment and intuition in deciding how to size up or respond to a situation. But they can guide and augment the process of choosing the most promising course of action. Consider once again the Helen Demarco case (Chapter Two). Her boss, Paul Osborne, had a plan for major change. Demarco thought the plan was a mistake but did not feel she could directly oppose it. What should she do? The issue of commitment and motivation was important, both in terms of her lack of support for Osborne's plan and her concern about finding a solution he could accept. The table suggests that the human resource frame was worth considering, though Demarco never did. The quality of the plan was critical in her judgment, but she was convinced that Osborne was immune to technical arguments.

Ambiguity played a significant role in the case. Even if technical issues were reasonably clear, the key issue of how to influence Osborne was shrouded in haziness. Implicitly, Demarco acknowledged the importance of the symbolism in using a form of theater (research that wasn't really research, a technical report that was window dressing) as her key strategy. Above all, Exhibit 15.2 suggests that Demarco's plight aligns best with the political frame: resources were scarce, conflict was high, and she was trying to influence from the bottom up. The choice point pressed toward politics and symbols. She went with the flow.

The guidelines in Exhibit 15.2 cannot be followed mechanically. Arriving at an adequate response for every situation is a matter of playing probabilities. In some cases, your line of thinking might lead you to a familiar frame. If the tried-and-true approach shows signs of producing a shortfall, though, reframe again. You may discover an exciting and creative new lens for deciphering the situation. Then you face another problem: how to communicate your breakthrough to others who still champion the old reality.

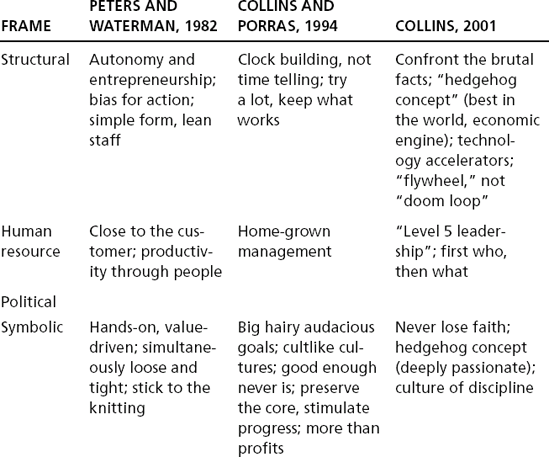

Does the ability to use multiple frames actually help managers decipher events and determine alternative ways to respond? If so, how are the frames embedded and integrated in everyday situations? We examine several strands of research to answer these questions. First, we look at three influential guides to organizational excellence: In Search of Excellence (Peters and Waterman, 1982), Built to Last (Collins and Porras, 1994), and From Good to Great (Collins, 2001). We then review three studies of managerial work, The General Managers (Kotter, 1982), Managing Public Policy (Lynn, 1987), and Real Managers (Luthans, Yodgetts, and Rosenkrantz, 1988). Finally, we look at recent studies of managers' frame orientations to see if current thinking is equal to present-day challenges.

Organizational Excellence

Peters and Waterman's spectacular best-seller In Search of Excellence (1982) explored the question, "What do high-performing corporations have in common?" Peters and Waterman studied more than sixty large companies in six major industries: high technology (Digital Equipment and IBM, for example), consumer products (Kodak, Procter & Gamble), manufacturing (3M, Caterpillar), service (McDonald's, Delta Airlines), project management (Boeing, Bechtel), and natural resources (Exxon, DuPont). The companies were chosen on the basis of both objective performance indicators (such as long-term growth and profitability) and the judgment of knowledgeable observers.

Collins and Porras (1994) attempted a similar study of what they termed "visionary" companies but tried to address two methodological limitations in the Peters and Waterman study. Collins and Porras included a comparison group (missing in Peters and Waterman) by matching each of their top performers with another firm in the same industry with a comparable history. Their pairings included Citibank with Chase Manhattan, General Electric with Westinghouse, Sony with Kenwood, Hewlett-Packard with Texas Instruments, and Merck with Pfizer. Collins and Porras emphasized long-term results by restricting their study to companies at least fifty years old with evidence of consistent success over many decades.

Collins (2001) used a comparative approach similar to that of Collins and Porras but focused on another criterion for success: instead of organizations that had excelled for many years, he identified a group of companies that had made a dramatic breakthrough from middling to superlative and compared them with similar companies that had remained ordinary.

Each of the three studies identified seven or eight critical characteristics of excellent companies, similar in some respects and distinct in others, as Exhibit 15.3 shows. All three suggest that excellent companies manage to embrace paradox. They are loose yet tight, highly disciplined yet entrepreneurial. Peters and Waterman's "bias for action" and Collins and Porras's "try a lot, keep what works" both point to risk taking and experimenting as ways to learn and avoid bogging down in analysis paralysis. All three studies emphasize a clear core identity that helps firms stay on track and be clear about what they will not do.

Two of the studies emphasized something they did not find: charismatic, larger-than-life leadership. Collins and Porras (1994) and Collins (2001) both highlighted leaders who were usually homegrown and focused on building their organization rather than their personal reputation. Collins's "level 5" leaders were driven but self-effacing, extremely disciplined and hardworking but consistent in attributing success to their colleagues rather than themselves.

As Exhibit 15.3 shows, all three studies produced three-frame models. Notice that none of the characteristics of excellence are political. Does an effective organization eliminate politics? Or did the authors miss something? By definition, their samples focused on companies with a strong record of growth and profitability. Infighting and backbiting tend to be less visible on a winning team than on a loser. When resources are relatively abundant, political dynamics are less prominent because slack assets can be used to buy off conflicting interests. Recall, too, that a strong culture tends to increase homogeneity—people think more alike. A unifying culture reduces conflict and political strife—or at least makes them easier to manage.

Even in successful companies, it is likely that power and conflict are more important than these studies suggest. Ask a few managers, "What makes your organization successful?" They rarely talk about coalitions, conflict, or jockeying for position. Even if it is a prominent issue, politics is typically kept in the closet—known to insiders but not on public display. But if we change our focus from effective organizations to effective managers, we find a different picture.

The Effective Senior Manager

Kotter (1982) conducted an intensive study of fifteen corporate general managers (GMs). His sample included "individuals who hold positions with some multifunctional responsibility for a business" (p. 2); each managed an organization with at least several hundred employees. Lynn (1987) analyzed five sub-cabinet-level executives in the U.S. government, political appointees with responsibility for a major federal agency. Luthans, Yodgetts, and Rosenkrantz (1988) studied a larger but less elite sample of managers than Kotter and Lynn. With a sample of about 450 managers at a variety of levels, they examined managers' day-to-day activities and reported how those activities related to success and effectiveness. Exhibit 15.4 shows the characteristics that these studies emphasize as being the keys to effectiveness.

Kotter and Lynn described jobs of enormous complexity and uncertainty, coupled with substantial dependence on networks of people whose support and energy were essential for the executives to do their job. Both focused on three basic challenges: setting an agenda, building a network, and using the network to get things done. Lynn's work is consistent with Kotter's observation: "As a result of these demands, the typical GM faced significant obstacles in both figuring out what to do and in getting things done" (Kotter, 1982, p. 122).

Kotter and Lynn both emphasized the political dimension in senior managers ' jobs. Lynn described the need for a significant dose of political skill and sophistication: "building legislative support, negotiating, and identifying changing positions and interests" (1987, p. 248). Kotter's model includes elements of all four frames; Lynn's includes all but the symbolic.

A somewhat different picture emerges from the study by Luthans, Yodgetts, and Rosenkrantz. In their sample, middle-and lower-level managers spent about three-fifths of their time on structural activities (routine communications and traditional management functions like planning and controlling), about one-fifth on "human resource management" (people-related activities like motivating, disciplining, training, staffing), and about one-fifth on "networking" (political activities like socializing, politicking, and relating to external constituents). The results suggest that, compared with the senior executives Kotter and Lynn studied, middle managers spend less time grappling with complexity and more time on routine.

Luthans, Yodgetts, and Rosenkrantz distinguished between "effectiveness" and "success." The criteria for effectiveness were the quantity and quality of the unit's performance and the level of subordinates' satisfaction with their boss. Success was defined in terms of promotions per year—how fast people got ahead. Effective managers and successful managers used time differently. The most "effective" managers spent much of their time on communications and human resource management and relatively little time on networking. But networking was the only activity that was strongly related to getting ahead. "Successful" managers spent almost half their time on networking and only about 10 percent on human resource management.

At first glance, this might seem to confirm the cynical suspicion that getting ahead in a career is more about politics than performance. More likely, though, the results confirm that performance is in the eye of the beholder. Subordinates rate their boss primarily on criteria internal to the unit—effective communications and treating people well. Bosses, on the other hand, focus on how well a manager handles relations to external constituents, including, of course, the bosses themselves. The researchers found that the 10 percent or so of their sample high on both success and effectiveness had a balanced approach emphasizing both internal and external issues. They were, in effect, multiframe managers.

Comparing all six studies—those focusing on organizations and those focusing on managers—reveals both similarities and differences. All give roughly equal emphasis to structural and human resource considerations. But political issues are invisible in the organizational excellence studies, whereas they are prominent in all the studies of individual managers. Politics was as important for Kotter's corporate executives as for Lynn's political appointees and was the key to getting ahead for middle managers. Conversely, symbols and culture were more prominent in the studies of organizational excellence. For various reasons, each study tended to neglect one frame or another. In assessing any prescription for improving organizations, ask if any frame is omitted. The overlooked perspective could be the one that derails the effort.

Yet another line of research has yielded additional data on how frame preference influences leadership effectiveness. Bolman and Deal (1991, 1992a, 1992b) and Bolman and Granell (1999) studied populations of managers and administrators in both business and education. They found that the ability to use multiple frames was a consistent correlate of effectiveness. Effectiveness as a manager was particularly associated with the structural frame, whereas the symbolic and political frames tended to be the primary determinants of effectiveness as a leader.

Bensimon (1989, 1990) studied college presidents and found that multiframe presidents were viewed as more effective than presidents wedded to a single frame. In her sample, more than a third of the presidents used only one frame, and only a quarter relied on more than two. Single-frame presidents tended to be less experienced, relying mainly on structural or human resource perspectives. Presidents who relied solely on the structural frame were particularly likely to be seen as ineffective leaders. Heimovics, Herman, and Jurkiewicz Coughlin (1993) found the same thing for chief executives in the nonprofit sector, and Wimpelberg (1987) found comparable results in a study of eighteen school principals. His study paired nine more effective and less effective schools. Principals of ineffective schools relied almost entirely on the structural frame, whereas principals in effective schools used multiple frames. When asked about hiring teachers, principals in less effective schools talked about standard procedures (how vacancies are posted, how the central office sends a candidate for an interview), while more effective principals emphasized "playing the system" to get the teachers they needed.

Bensimon found that presidents thought they used more frames than their colleagues observed. They were particularly likely to overrate themselves on the human resource and symbolic frames, a finding also reported by Bolman and Deal (1991). Only half of the presidents who saw themselves as symbolic leaders were perceived that way by others.

Despite the low image of organizational politics in the minds of many managers, political savvy appears to be a primary determinant of success in certain jobs. Heimovics, Herman, and Jurkiewicz Coughlin (1993, 1995) found this for chief executives of nonprofit organizations, and Doktor (1993) found the same thing for directors of family service organizations in Kentucky.

The image of firm control and crisp precision often attributed to managers has little relevance to the messy world of complexity, conflict, and uncertainty they inhabit. They need multiple frames to survive. They need to understand that any event or process can serve several purposes and that participants are often operating from different views of reality. Managers need a diagnostic map that helps them assess which lenses are likely to be salient and helpful in a given situation. Among the key variables are motivation, technical constraints, uncertainty, scarcity, conflict, and whether an individual is operating from the top down or from the bottom up.

Several lines of research have found that effective leaders and effective organizations rely on multiple frames. Studies of effective corporations, of individuals in senior management roles, and of public and nonprofit administrators all point to the need for multiple perspectives in developing a holistic picture of complex systems.