3

Three Pillars to Support a Balanced Society

IN JAMES CLAVELL’S NOVEL Shogun, the Japanese woman tells her British lover, confused by the strange world into which he has been shipwrecked, “It’s all so simple, Anjinsan. Just change your concept of the world.” To regain balance, we, too, just have to change our concept of the world. A good place to start is by reframing the political dichotomy that for two centuries has narrowed our thinking along one straight line.

The Consequences of Left and Right

Since the late eighteenth century, when the commoners sat to the left of the speakers in the French legislatures and the ancien régime to the right, we have been mired in great debates over left versus right, states versus markets, nationalization versus privatization, communism versus capitalism, and on and on. A pox on both of these houses. We have had more than enough sliding back and forth between two unacceptable extremes.

Capitalism is not good because communism proved bad. Carried to their dogmatic limits, both are fatally flawed. “So long as the only choice is between a voracious market and a regulatory state, we will be stuck in a demoralizing downward spiral” (Bollier and Rowe 2011:3). To put it in terms of contemporary politics, too many countries now swing fruitlessly between left and right, while others sit paralyzed in the political center.

Pendulum and Paralyzed Politics

It is surprising how many voters now line up obediently on one side or the other of the political spectrum. Left or right, most voters see everything as black and white. Discussion has given way to dismissal and trust to suspicion, while nastiness takes center stage.

It is even more surprising how many countries are split so evenly between such voters. “Between 1996 and 2004 [Americans] lived in a 50–50 nation in which the overall party vote totals barely budged five elections in a row” (Brooks 2011d).

In such elections, a few voters in the center determine the winner. They may want moderation, but by having to cast their votes one way or the other, they often get domination: the elected party carries the country far beyond what its vote justifies, to serve its minority while ignoring the majority, including some of the people who helped get it elected. Egyptians in 2012 got the Muslim Brotherhood, while Americans in 2000 who voted for George W. Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” got his tragic war in Iraq.

These center voters eventually get fed up and switch—if they still have the choice—so the country ends up in pendulum politics: up goes the right and down goes the left, until up goes the left and down goes the right, as each side seeks to cancel the accomplishments of the other. Or else the country stays up on one side as the elected leader becomes a dictator.

Countries with larger numbers of moderate voters tend to get more moderate politics, with governments closer to the center. This may be a better place, with its penchant for compromise. But as Mary Parker Follett pointed out (see the box in Chapter 2), that place has its own problems. Coalitions of compromise, de facto or de jure, have to negotiate everything, left and right. The country can end up with micro solutions for its macro problems or, worse, fall into political gridlock.

Power to the Entitled

While politics gets gridlocked, or swings back and forth fruitlessly, society itself is not disabled: private power proliferates. As the politicians debate marginal changes in their parochial legislatures at home and offer lofty pronouncements at their grand conferences abroad, powerful corporations so inclined bolster their entitlements, by busting unions, reinforcing cartels, manipulating governments,11 and escaping whatever taxes and regulations remain. All of this behavior is cheered on by economists who revel in such freedom of the marketplace, while the world tumbles into imbalance.

Protesting What Is While Confusing What Should Be

In recent years, protests have erupted in various parts of the world—for example, in the Middle East over dictatorships and in Brazil over corruption. The United States has experienced occupations from the left and Tea Parties from the right, both clearer about what they oppose than what to propose. For example, included in the “Non-negotiable Core Beliefs” on the Tea Party website are the following tenets: “Gun ownership is sacred” and “Special interests must be eliminated.” The gun lobby is apparently not a special interest!

The protestors in the streets of the Middle East have not been confused. Beside jobs and dignity, they were out for liberty and democracy—the freedom to elect their leaders. Yet this is what the occupiers of the streets of America were rejecting: the liberty of the 1 percent, a democracy of legal corruption, the freedom of free enterprises. The protestors of Egypt got to elect their leaders, all right: in came the Muslim Brotherhood. Welcome to twenty-first-century democracy!

So back they went into the streets, this time clearer on what they didn’t want than what they did. The army removed the Brotherhood, with consequences that now appear to be dire. I hope that well-meaning Egyptians will figure out how to resolve this mess, because many of us in Canada right now have the same concern: how to get a government that integrates our legitimate needs instead of favoring narrow interests.

Some pundits in the West who were quick to understand the early protests in the Middle East pronounced themselves confused by the protests closer to home. “Got a gripe? Welcome to the cause” headlined the International Herald Tribune (Lacey 2011). Yes, the gripes have varied—unemployment, income disparities, banker bonuses, global warming. But what has been behind most of these protests—east and west, north and south, left and right—should be obvious to anyone who cares to get the point: people have had it with social imbalance.

So no, thank you, to a compromised center as well as to the pendulum politics of left and right, both of which buttress imbalance. We need to change our concept of the political world.

Public, Private, and Plural Sectors

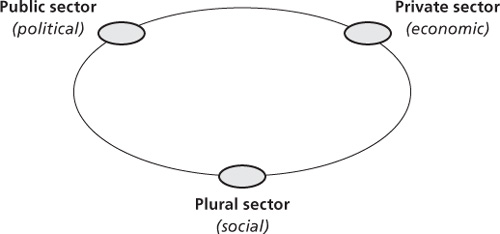

Centuries of debate over left versus right have given the impression that society has only two consequential sectors: the public and the private. In fact, there are three, and the other one may be the most consequential today, because it can be key to restoring balance in society.

Fold down the ends of the political line into the circle shown in the accompanying figure. This perspective can take us past two-sided politics, to a three-sector society, representing governments, businesses, and communities. Strength in all three sectors is necessary for a society to be balanced. Imagine them as the sturdy legs of a stool—or pillars, if you wish—on which a healthy society has to be supported: a public sector of political forces rooted in respected governments, a private sector of economic forces based on responsible businesses, and a plural sector of social forces manifested in robust communities (Korten 1995; Marshall 2011: Chapter 20). The public and private sectors are shown to the left and right of the upper part of the circle because their institutions function mostly in hierarchies of authority, off the ground. The plural sector is shown at the bottom because its associations tend to be rooted on the ground; we may all get services from public and private sector intuitions, but all of us are the plural sector.

To put this in another way, a democratic society balances individual, collective, and communal needs, attending to each adequately but none excessively. As individuals in our economies, we require responsible businesses for much of our employment and most of our consumption of goods and services. As citizens of our nations and the world, we require respected governments for many of our protections, physical and institutional (such as policing and regulating). And as members of our groups, we require robust communities for many of our social affiliations, whether practicing a religion or engaging in a community cooperative.

The societies called communist and capitalist have each tried to balance themselves on one leg. It doesn’t work. The former has failed to satisfy many of its people’s needs for consumption; the latter is failing to satisfy some of its citizens’ most basic needs for protection. Trying to balance society on two legs, one public, the other private—as many countries now do—may work better, but it is not working well, because of those politics of compromise. The key to renewal is thus the third leg: by taking its place alongside the public and private sectors, the plural sector can not only help to maintain balance in society, but also lead the process of rebalancing society that we so desperately require.

Welcome to the Plural Sector

“If men are to remain civilized or to become so, the art of associating together must grow and improve” (de Tocqueville 1840/2003: 10). Accordingly, let’s take a good look at the sector that best encourages this activity.

What’s in the Plural Sector?

The answer is suggested in the word itself: a great number of activities. All of them are associations (as de Tocqueville used the term), but only some of them are formal institutions, in the sense of being legally incorporated. The latter include cooperatives, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), unions, religious orders, and many hospitals and universities. Less formal associations include social movements, whereby people mass together to protest some practice they find unacceptable; and social initiatives, usually started by small groups in communities, to bring about needed changes. Metaphorically speaking, social movements materialize in the streets while social initiatives function on the ground. Both are found in the plural sector because it offers the autonomy needed to challenge the status quo, with relative freedom from the controls of public sector governments and the expectations of private sector investors.

What can such a variety of activities have in common, to distinguish them from what goes on in the public and private sectors? The answer is ownership: the plural sector comprises all associations of people that are owned neither by the state nor by private investors. Some are owned by their members; others are owned by no one.

Cooperatives are owned by their members—for example, the customers of a retail co-op and the workers of an industrial co-op. Each member has a single share that cannot be sold to any other member. Similar ownership can be found in professional associations and kibbutzim.

Few people realize the extent of the cooperative movement. Amul, a dairy cooperative in India, has 3 million members. Mondragon, in the Basque region of Spain, is the world’s largest worker cooperative, with 80,000 employees, in businesses that range from supermarkets to machine tool manufacturing. The United States is home to about 30,000 cooperatives, with memberships totaling 350 million, more than the country’s entire population.

Owned by no one are many more associations: foundations, clubs, religious orders, think tanks, activist NGOs such as Greenpeace, and service NGOs such as the Red Cross. Almost all the hospitals in Canada fall into this category: they may be funded by government but they are not owned by government. In the United States, the figure is about 70 percent. Called “voluntary,” these hospitals may be supported by donors but are not owned by them, or anybody else. Included here are most of the country’s renowned hospitals; the majority of the country’s most renowned universities are likewise owned by no one. (By the way, one of them, the University of Chicago, has been the plural sector home of many of the economists who have promoted the supremacy of the private sector most aggressively. If capitalism is so good for everyone else, how come it has not been good enough for these economists?)

Gaining attention these days is the social economy, comprising plural sector associations that engage in trade. Cooperatives are obvious examples—they are businesses, even if member owned—but so, too, are many non-owned associations, such as Red Cross chapters that sell swimming lessons.

By virtue of being owned by their members or by no one, plural sector associations can be more egalitarian and flexible, and so typically less formally structured, than comparable businesses and government departments. Indeed, many of the activities in this sector are hardly structured at all. Think of a community that self-organizes to deal with a natural disaster or a group of friends who get together to stop some environmental threat. In fact, this is how Greenpeace got its start. A couple of people sitting in a living room in Vancouver got a call from a newspaper reporter asking about the environment movement, and one of them blurted out that they were going to challenge a weapons test off the Alaska coast. They raised some money at a concert, bought an old fishing boat, named it Greenpeace, and headed out. The photo of this little boat in front of the gigantic hull of that carrier became iconic in this renowned institution.

The Obscurity of the Plural Sector

Despite this variety of activities, with so many of us involved in them and many of them so prominent, it is remarkable how obscure the plural sector itself is. Having been ignored in those great debates over left versus right has obviously not helped.12 Activities in the plural sector range across that whole political spectrum; it is no middle ground between left and right, but as different from the public and private sectors as they are from each other.

Over many years, we have seen a good deal of nationalization and privatization, as institutions have been shifted back and forth between the public and private sectors. Where has the plural been in all this, which can sometimes be a better fit for organizations that don’t quite suit the other two? Likewise, there is much talk these days about PPPs, meaning partnerships between public and private institutions. How about the institutions of the plural sector? Great debates have also raged over the provision of health care services in markets, for the sake of choice, or else by governments, for the sake of equality. How about the plural sector, for the sake of quality?13 Think of the hospitals you admire most. Are they public? Or private?

Why Call It “Plural”?

Labels matter. Another reason for the obscurity of this sector is the set of unfortunate labels by which it has been identified. These include (1) the “third sector,” as if it is third-rate, an afterthought; (2) the home of “not-for-profit” organizations, even though governments are not-for-profit, too, and of NGOs, even though businesses are also nongovernmental; (3) the “voluntary sector,” as if this were a place of casual employment; and (4) “civil society,” the oldest yet most confusing label, hardly descriptive in and of itself (in contrast to uncivil society?).14 Recently I attended a meeting of scholars dedicated to this sector and heard most of these labels mentioned in the course of an hour. If the experts can’t get their vocabulary straight, how are the rest of us to take this sector seriously?

I propose the word plural because of the variety of associations in this sector as well as the plurality of their membership and ownership.15 Not incidental is that the word starts with a p: when I have introduced it in discussion groups, plural has entered the conversations naturally alongside public and private.16

Common Property in the Plural Sector

The plural sector is distinguished not only by its unique forms of ownership but also by a form of property particular to itself.

For centuries, property has been seen as absolute, based on some sort of natural law, even God-given—whether it was obtained by hard work, purchase, manipulation, or inheritance. Today the business corporation is seen as the property of shareholders, even those who are day traders, while employees who devote their working lives to the company are excluded. Marjorie Kelly (2001) has likened this to the ownership of land in feudal times.17

The fact is that property “rights” have always been established by human actions, whether according to the law of the jungle or the laws of the state, these usually written by people with considerable property of their own.18 Communism taught us that a society with hardly any private property cannot function effectively. Capitalism is teaching us that a society with hardly anything but private property is not much better.

Now we hear a great deal about “intellectual property”: if you have an idea, patent it, in order to “monetize” it, even if your claim is dubious. Some pharmaceutical companies, for example, have been able to patent herbal medicines that had been serving people in traditional cultures for centuries.

Benjamin Franklin had another idea: he refused to patent what became his famous stove, commenting, “We should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any innovation of ours.” Jonas Salk concurred: “Who owns my polio vaccine? The people. Can you patent the sun?”19 Think of all the children who have benefitted from not having to bear the burden of that market.

Franklin and Salk engaged in a role we call “social entrepreneur.” Were they foolish to forego all that money? Maybe the foolish ones are those who have to accumulate money relentlessly in order to keep score. “The determination to do something because it is the right thing to do, not because we are told to do it by governments or enticed to do it by the market, is what makes associational life a force for good, [and] provides fuel for change” (Edwards 2004: 111).

If this stove and vaccine were not registered as private property, and if they were not public property owned by the state, what were they? The answer is common property. It used to be quite common before it disappeared from public perception.20 The Boston Common, for example, now a prominent park, was once the place where the landless could graze their cows. A sign at its entrance makes no mention of that origin.

Common property is associated with the plural sector in that it is communal and shared but not owned: it is held by people “jointly and together rather than separately and apart” (Rowe 2008: 2; see also Ostrom 1990 and Ostrom et al. 1999). Think of the air we breathe—try to own that—or the water that some farmers share for irrigation. Now we are seeing a resurgence of common property in interesting ways, most evidently in open-source systems such as Linux and Wikipedia, non-owned associations whose users create and share the contents.

Today [the common property] model is reappearing in many precincts of the economy at large—from the revival of traditional main streets, public spaces, and community gardens to the resistance to the corporate enclosure of university research and the genetic substrate of material life. (Rowe 2008: 139)

So the commons is making a comeback. Good thing, because it can allow common knowledge to replace the patent nonsense associated with much of that “intellectual property.” Believe in common property—replace the market lens of economics with the community lens of anthropology—and you will see it all over the place.21

Communityship Alongside Ownership, Leadership, and Citizenship

We need a new word to take its place alongside the collective citizenship of the public sector and the individual ownership in the private sector as well as the personal leadership that is emphasized in both these sectors. Communityship designates how people pull together to function in collaborative relationships. Between each of us as individuals and all of us in society is the communal nature of our groups: we are social beings who need to identify, to belong. Think of our clubs and so many of our other informal affiliations in the plural sector.

On the formal side, organizations, in all the sectors, function best as communities of human beings, not collections of human resources. But the associations of the plural sector have a special advantage in this regard. With their people free of pressures to maximize “value” for shareholders they never met or to submit to the controls so prevalent in government departments, they can function like members with a purpose more than employees in a job. And with the egalitarian nature of many plural sector organizations as well as associations, these people are inclined to be naturally engaged—they don’t have to be formally “empowered.” Think here of volunteer firefighters and hospital nurses as well as protesters in mass movements. “At its best, civil society is the story of ordinary people living extraordinary lives through their relationships with each other” (Edwards 2004: 112). Imagine a society made up of such organizations, across all the sectors.

Losing Their Way

Of course, there are those plural sector organizations that fail to take advantage of this potential. Forced by their board or “CEO” to adopt unsuitable business practices, or driven by their funders to apply overly centralized controls, they lose their way.22

These days the fashionable practices of big business are considered to be the “one best way” to manage everything: grow relentlessly, measure obsessively, plan strategically, and call the boss “CEO” so that he or she can lead heroically, while being paid obscenely. So much for communityship. Many of these practices have become dysfunctional for business itself, let alone for the plural and public sector organizations that imitate them.23

The problem with leadership is that it’s all about the individual. Use the word and you are singling out one person from the rest, no matter how determined he or she may be to engage them all. Sure, an individual can make a difference. But how often these days is that for the worse? The more we obsess about leadership, the less of it we seem to be getting, alongside more narcissism.24 So let’s make room for collaborative communityship in the space between individual leadership and collective citizenship.

The Fall (and Rise?) of the Plural Sector

Two centuries ago Alexis de Tocqueville characterized the United States as replete with community associations.25 Intent on limiting the power of government, the people of America preferred to organize for themselves, in plural sector associations alongside private sector businesses.

More recently, however, Robert Putnam (1995, 2000) has written about the demise of the former, under the metaphor “bowling alone”—the isolation of the individual Why has there been a steady “erosion of the community institutions that we all depend on,” such as schools, libraries, and parks? (Collins 2012: 8). One explanation has certainly been the increasing dominance of the private sector. But no less significant have been forces of both a political and a technological nature.

Besieged from Left and Right

It is evident that the domination of communism in some countries debilitated their private sectors while the domination of capitalism in some others has been overwhelming their public sectors. Less evident is that both systems have relentlessly undermined the plural sector. To achieve balance in society, we need to understand why.

Communist governments have never been great fans of community associations (as remains evident in China), for good reason: the independence of these associations is a threat to their omnipotence.26 “A despot easily forgives his subjects for not loving him, provided they do not love one another” (de Tocqueville 1840/2003: 102).

But despots are not alone in this marginalization of the plural sector: many elected governments have also been hard on community associations, sometimes for no other reason than the convenience of their administrations—for example, by forcing mergers of community hospitals into regional ones and amalgamations of small towns into bigger cities. Community figures hardly at all in a prevailing dogma that favors economic scale, no matter what the social consequences.

For much the same reason, many big corporations are not great fans of local community associations. Consider how Walmart has blocked efforts to unionize its stores, likewise that global fast-food chains have hardly been promoters of local cuisines, or global clothing retailers of local dress. There is a homogenizing imperative in globalization that is antithetical to the distinctiveness of communities. As a consequence, while private sectors have been expanding globally, plural sectors have been withering locally.27

Undermined by New Technologies

Perhaps even more detrimental to the plural sector is that a succession of new technologies—from the automobile and the telephone to the computer and the Internet—have reinforced the isolation of the individual to the detriment of social engagement.

Consider the automobile: wrap its sheets of metal around many of us and out comes road rage. Have you ever experienced sidewalk rage, let alone been tailgated by someone walking behind you on a sidewalk (unless, of course, that person was texting on a mobile phone)?

Thanks to automobile technology, many local communities have become urban agglomerations where people hardly know each other. “Market” used to designate the place where people congregated to talk as well as to shop—it was the heart and soul of the community. Today the word market mostly designates the opposite: places that are coldly impersonal, whether the stock market or the shopping mall.

Electronic devices, the new technologies of our age, are hardy better: they put our fingers in touch, at least with a keyboard or a screen, while the rest of us sits there, often for hours, typing and shopping alone. No time even for bowling.

The social media—Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter—certainly connect us to whoever is on the other end. But don’t confuse networks with communities. (If you do, try to get your Facebook “friends” to help paint your house, let alone rebuild your barn.)28 These technologies are extending our social networks in amazing ways, but often at the expense of our personal relationships. Many people are so busy texting and tweeting that they barely have time for meeting and reading. Where is the technology for meaning?29

In his New York Times column, Thomas Friedman (2012) reported asking an Egyptian friend about the protest movements in that country: “Facebook really helped people to communicate, but not to collaborate,” he replied. Friedman added that “at their worst, [social media] can become addictive substitutes for real action.” That is why, although the larger social movements, by facilitating communication, may raise consciousness about the need for renewal, it is usually smaller social initiatives, developed in collaborative community groups, that figure out how to do the actual renewing.

Is the plural sector making a comeback? A New York Times article indicated that American “nonprofits have been growing at a breakneck pace” (Bernasek 2014), perhaps partly because governments have not been able to accommodate the full measure of our social needs. Likewise, as just noted, the new social media are proliferating. By facilitating connections among people, they help those

with common cause to find each other, even in the same city, let alone across the globe. By so connecting with each other, community groups can carry their initiatives into broader movements.

Will these developments compensate for the debilitating effects that the new technologies have had on traditional forms of associating? We can’t tell yet, but let’s hope so. Hence, once again, please welcome the plural sector. But be careful.

Beyond Crude, Crass, and Closed

The benefits of the plural sector should now be evident—I hope as evident as those of the private and public sectors. But this sector is no more a holy grail than are the other two. We have had more than enough dogma from communism and capitalism, thank you. The plural sector is not a “third way” between the other two sectors but, to repeat what needs repeating, one of three ways required in a balanced society.

Each sector suffers from a potentially fatal flaw. Governments can be crude. Markets can be crass. And communities can be closed—at the limit, xenophobic. Concerning “crude,” I heard the story about a sixty-year-old having to show proof of age in order to buy a bottle of liquor at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. After all, when it comes to the laws of the state, doesn’t everyone have to be treated equally? At airport security, every time a terrorist gets a new idea, governments impose some new humiliation. As for “crass,” in 2012 Air Canada advertised a seat sale: Montreal to London, return, for $274. What a bargain—leaving aside the “taxes, fees, charges, and surcharges,” which raised the total to $916. (A CNN.com report [Macguire 2012] referred to this as “common industry practice.” That’s the point.) And “closed” can be experienced by attending a sermon of some priest, pastor, imam, or rabbi who exhorts people to remain loyal to the faith without explaining why.

These examples may be mundane. Far worse things happen when one sector dominates a society. Under Eastern European communism, the crudeness of the public sector was overwhelming. And with so much predatory capitalism about, we live in societies that are increasingly crass. “Caveat emptor”—let the buyer beware—even if that be a child watching advertisements on television. “Charge what the market will bear,” even if sick people have to die for want of available medicines. What kind of a society tolerates such things?

In the plural sector, populism seems to be its most evident political manifestation, since its roots usually lie in mass movements outside the established institutions of government and business. A populist government can apply its power inclusively, to serve much of the population, or else exclusively, for the benefit of its own adherents (as we shall discuss later). When the latter becomes oppressive, populism can turn into fascism, as it did in Nazi Germany.

Crudeness, crassness, and closed-ness are countered when each sector takes its appropriate place in society, cooperating with the other two while helping to keep both—and their institutions—in check. I am delighted to get many of my goods and services from the private sector and much of my protection and infrastructure (law enforcement, highways, and so on) from the public sector. And I generally look to the plural sector for the best of my professional services—higher education, hospital care—even when they are funded by the public sector and supplied by the private sector.

We just have to be careful not to mix these sectors up, by allowing the dogma of the day to carry activities away from the sector where they function most appropriately. I no more want a private company patrolling my streets than I want a government department growing my cucumbers. And please keep the politicians and the businesspeople at arm’s length from the education of our children, without allowing some people of the plural sector to restrict its use for their own narrow advantage.

Is a Balanced Society Even Possible?

Are we hardwired to favor privilege, where power has to concentrate in a few hands—some inevitable 1 percent? History bears witness to a steady parade of this: lords and peasants, commissars and proletarians, shareholders and workers. On and on it has gone, unstoppable for millennia, to our own day. “Stockholders claim wealth they do little to create, much as nobles claimed privilege they did not earn” (Kelly 2001: 29).

Perfect balance is unattainable: some people will always end up on top. Why not, if they have earned it, by protecting people from threats, inventing a new practice, or creating substantial employment? But what if they have come to power through underhanded manipulation, or retained their power for too long, or inherited it for no better reason than birth? Too many people in powerful positions have engaged in reckless wars, built themselves extravagant monuments at the expense of others, or bullied their employees.

In government, there used to be no way to throw the scoundrels out, short of assassination, coup d’état, or civil war. Then along came democracy, circa 1776. With the sovereigns and the aristocrats gone came a new way to throw the scoundrels out, or at least restrain their shenanigans. All men created equal had a say in who led them. Democracy hardly ended privilege, however—that begins with how we are nourished in the womb and never stops. But at least all those men, and later women, gained a shot at getting to the top themselves. This became the great American dream, known as “social mobility.”

Of course, things were never totally like that in America. But they came close enough to sustain the myth. And this democracy circa 1776 helped produce the most remarkable period of growth in human history, socially and politically as well as economically—two hundred years’ worth, from 1789 to 1989.

Fast-forward to today and have another look at that social mobility. A 2010 report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development put the Nordic countries plus Australia, Canada, Germany, and Spain ahead of the United States. For example, a son’s advantage in having a higher-earning father was 47 percent in the United States, 19 percent in Canada. “Your [American] parents’ income correlates more closely with your chance of finishing college than your SAT scores do—class matters more than how you do in class” (Freeland 2012; see also the discussion at the end of the appendix of “Democracy in America—Twenty-five Years Later”).

So the expectations raised high by the American dream now go increasingly unmet, although the myth of social mobility carries on. Success stories do appear; it’s just that the odds have changed, and the losers are the prime casualties of the escalating exploitation.

Much of the world has rid itself of insane emperors, bloodthirsty conquerors, and voracious colonizers (although shades of all three are appearing again). But not greedy acquirers—quite the contrary. Every country has its scoundrels, but now many of them are outside government, albeit manipulating within it. Short of catching them engaging in criminal activity—and sometimes even then—there is no way to get rid of these scoundrels.

Of course, competitive markets are supposed to take care of such behavior: fail to serve your customers properly, and you will be replaced by whoever does. This sounds good, were it not for those markets of entitlement that favor the already privileged. Elected officials, who should be putting the scoundrels in jail, instead cater to them, to keep those political donations coming.

Nearly two hundred years ago, de Tocqueville asked, “Can it be believed that the democracy which has overthrown the feudal system and vanquished kings will retreat before tradesmen and capitalists?” (1840/2003: 6). Now he has his answer: yes.

Must this remain the answer? Let’s hope not. In fact, the U.S. Constitution offers us a way to think about this. Its famous checks and balances, as noted, have applied thus far only within government. So maybe it’s time to apply them beyond government. Why not complete the American Revolution, in nations and the globe, by establishing renewed checks on dysfunctional activities in the private sector, for the sake of balance across the sectors?

Of course, such balance does not mean some perfectly stable equilibrium. That would just constitute a new dogma, incapable of renewing itself as society evolves. Healthy development—social, political, and economic—allows power to shift among the sectors according to need, in a dynamic equilibrium that encourages responsiveness without domination. And that brings us to the question of radical renewal.