The objectives of this article are: to inform the reader of the high need for creativity in our personal and professional lives; to increase the reader’s awareness of some of the behaviors and conditioning that affect the creativity in ourselves and others; to share with the reader a working definition of creativity and creative problem solving and how to put these skills of mind to practical use; to introduce some specific techniques that will enable the reader to improve his or her own creative thinking skills; and to show the reader how focusing our thought processes combined with a systematic approach to problem solving can help us make positive change in our lives.

Creativity is crucial for business today. Robert W. VanCamp, President and CEO of R. J. Reynolds Development Company, has said:

The survival skills of the nineties will be different. In a word, the most important skill is adaptability. The successful people, from now on—the leaders—will be the first to see change, and the earliest to adapt to it. The losers will be those who seek the old comfortable constancy…. And the successful manager will be one who can build an environment where creativity is encouraged—even demanded.1

When I use the word organization here, I am using it in its broadest sense, to include everything from an individual to any group of people that assemble, communicate, and work together for some common purpose. Therefore, it refers to both profit and nonprofit groups. Paul E. Mott wrote about adaptability in 1972 in his book The Characteristics of Effective Organizations. Mott found the following three characteristics common among what he considered effective organizations:

Efficiency. Efficiency is organizing for routine production. On a personal level, routine includes everything from how we get up in the morning, shower, dress, etc., to the set of patterns we use to communicate and relate to each other. Routines in our professional world include those series of steps to acquire, manufacture, distribute, market, and sell products. In the professional world, routines are in place to deliver a high quantity and a high quality of product or service.

Adaptability. Adaptability is organizing to change routines. In order to change routines, an organization must be aware of and in touch with their set of routines. Also, they must have a desire or motivation to change routines. This motivation can come from anticipating problems or changes and reacting to them. Adaptability in the professional world particularly requires that one stay abreast of new methods and technology applicable to the activities of that organization. Adaptability also requires that new methods or routines are sought out, accepted, and implemented once found.

Flexibility. Flexibility is organizing to cope with temporary, unpredictable overloads or emergencies. On a personal level, flexibility comes into play when we have a flat tire or must take care of the children when they are sick. On a professional level, flexibility comes into play when dealing with work stoppages, absenteeism, fuel shortages, raw material shortages, etc.

If one takes a hard look at organizations today it would seem that adaptability efforts tend to take a back seat to efficiency efforts. Costs, quality, quantity, and “the checkbook balance” are our measures of performance and the outcomes we typically focus upon. How we get these numbers or outcomes, i.e., our set of routines, rarely seems to be the focus of our attention. Our first question tends to be, “What is the number?” and not, “How did we get the number?” Most organizations track their efficiencies very closely and may not even know how to track their adaptability efforts. If an organization is to be effective, then the key question must be, “How might we get our adaptability efforts in line (or in balance) with our efficiency and flexibility efforts?”

To operate in the 1990s, organizations must become more adaptable so they can handle the rapid rate of change, the more complex systems, and the increasing demands of customers and other organizations.

Applied creativity is a necessary tool to help an organization balance its adaptability and efficiency efforts. The likely challenge for an old, established industry which has probably “ironed out efficiency problems” is to be more adaptable. Creative problem solving (CPS) can help. The most likely challenge for a new, emerging industry is to better establish its routines and be more efficient. Depending on the industry, the competitive environment, and all of the surrounding circumstances, applied creativity is necessary to get an organization what it needs to be successful. Growth and change are inevitable. The question is, “Are you proactive and creating what you want?” or “Are you reactive to what is happening around you?”

Figure 1 shows where an established, traditional organization might be: high in efficiency and low on adaptability. Applied CPS can help this organization find and solve problems to help it be more adaptable.

CPS, which can be defined as a set of tools or methods which an individual or organization can use to approach a problem or challenge and make effective changes, can help individuals and organizations to be more adaptable. This approach requires that the creativity of individuals be used.

Making use of the creativity of an individual is not necessarily an easy task. The average adult probably uses only a fraction of his or her creative ability. People tend to let things happen instead of making them happen because it is a more comfortable, risk-free way of doing things. But there is abundant research showing that everyone has the basic ability to be creative, and that everyone’s creativity can be enhanced. Given the rapidly changing environment of the 1990s, being adaptable will require individuals to be proactive versus comfortably reactive.

Let me offer the following definition of creativity:

Creativity = Knowledge × Imagination × Evaluation

Innovation = Creativity × Action

It is valid to argue that you cannot truly have creativity without taking action. In this case creativity and innovation are synonymous. Therefore:

Creativity = Knowledge × Imagination × Evaluation × Action

Just as with any equation, if knowledge, imagination, evaluation, or action is equal to zero, then creativity would equal zero.

To effectively use the concept that creativity is made up of some combination of knowledge, imagination, evaluation, and action, it is helpful to have a process. As Peter Drucker (1968, p. 35) says, “Entrepreneurs [must] … learn to practice systematic innovations.”

Let’s first address the imagination and evaluation parts of creativity (see Figure 2). Consider that the brain has four basic functions; it must: absorb, use the five senses to take in information; retain, log, hold, and recall information; diverge, use knowledge and imagination to generate facts, challenges, ideas, and action steps; and converge, use logic and judgment to evaluate alternatives.

Many people believe that creativity is our ability to do only divergent thinking. Creativity actually involves both divergent and convergent thinking. Unfortunately, our brains do not diverge and converge very well at the same time. Try finding one hundred different ways to improve a pencil while stopping after each new idea and evaluating it. After three hours and fifteen ideas have been discussed, the remaining eighty-five ideas will be hard to find. Said another way, trying to diverge and converge at the same time is like trying to drive with your brakes on. You will burn up lots of energy and go nowhere (see Figure 3).

Instead of diverging and converging at the same time, if we separate these activities or ways of thinking, we should end up with a better overall output. The best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas. Said another way, if we are good divergent thinkers and we can use our imagination to come up with many possibilities, then our chance of having better alternatives is improved.

One unfortunate thing about being an adult is that we have been highly conditioned to use our skills of logic and evaluation. As a result, we have lost much of our ability to use our imagination and therefore our ability to generate options. Our ideation-evaluation process looks more like that shown in Figure 4.

We are conditioned to think convergently for many reasons: We get rewarded for the decisions we make, i.e., the alternatives we select. We get rewarded for coming up with the answer the boss wants. We must make quick decisions and no time is allowed for looking for alternatives. Since we started our educational process, we were conditioned to look for that one correct answer versus finding many possible answers. (What percent of all questions that you had in school had one and only one answer? If you went to a technical school, the percentage must be above 95 percent.) To perform well in school, we learned to be good convergent thinkers.

To improve your ability to diverge or use your imagination, the following guidelines will help:

1. Do not use evaluation or logical thinking; defer judgment.

2. Strive to get a high quantity of ideas.

3. Strive to maintain an uninterrupted stream of ideas.

4. Dream up radical, impossible, or blue-sky ideas.

5. Build on existing ideas; change or improve ideas to create more.

6. Visualize or think in pictures and use your five senses to find more possibilities.

7. Relax and think that any idea is a good idea. Quantity, not quality, is the goal.

For individuals to improve their ability to think divergently, practice and patience are required. Many years of conditioning and thinking cannot be changed quickly. For many whose thinking ability has been out of balance for a long period of time, getting these skills of divergence and convergence in balance again will take a concentrated effort. An example may help. Pretend your right arm and left arm are equally strong and flexible. If you break your right arm and it is placed in a cast for eight weeks, it will no longer be equivalent in strength and flexibility to your left arm. Our skill or ability to use our imagination has been “put in a cast” as we have grown into adulthood. Please note that balancing thinking skills will not be easy if the environment and people continue to emphasize and reward only convergent thinking.

Particular importance should be placed on the fact that creativity takes both divergent and convergent thinking. If an individual has a highly divergent and imaginative mind but is not skilled at convergence or skillfully evaluating, the final results can still suffer (see Figure 5).

The key for helping most people balance their ability to do divergent and convergent thinking is improving one’s ability to defer judgment. Deferring judgment does not mean that judging or evaluation will not occur. It only means that during the ideation or divergent process your judgment and evaluation are suspended or withheld until many facts, challenges, or alternatives are generated. Once you have many possible options, then, and only then, is it time to evaluate.

Having the skills of divergent and convergent thinking is not enough to be creative and make change occur. As the definition of creativity offers, knowledge and action must be added to our skills of imagination and evaluation in order for creativity to unfold. Creative problem solving is one vehicle or tool which allows these necessary ingredients to come together to enable us to make change. Having only the skills of divergent and convergent thinking is like having a thousand gallons of gasoline. You can make a lot of smoke and fire but you cannot go anywhere. Creative problem solving as a tool is like having the vehicle in which to pour the gasoline.

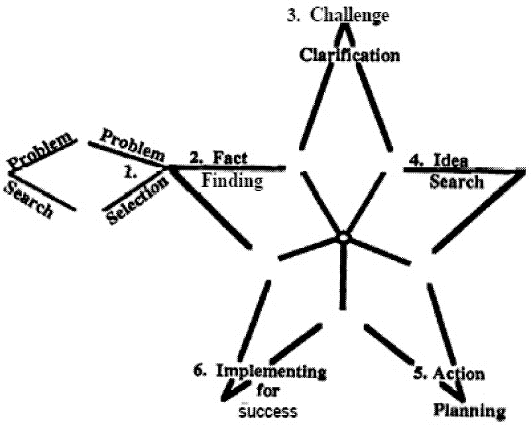

For making change and solving problems, the problem-solving model, which requires the use of knowledge and ends in implementation, in Figure 6 is offered.

Notice in the problem-solving model in Figure 6 that there is a divergent and convergent symbol (< >) that makes up each step of the model. By using the power of divergent and convergent thinking step, an individual or group can fully tap their thinking to its full potential—being creative and logical as they use a structured process to address any problem.

This creative problem-solving model works as follows:

STEP 1: Problem Finding

Diverge: Here an individual (or group) will generate a list of problems, situations, challenges, or goals that they might have.

Converge: Pick a problem that the individual (or group) wants to work on and has the skills, decision-making capability, power, energy, and ability to solve.

STEP 2: Fact Finding

Diverge: List facts that the individual (or group) knows about the situation. Consider facts about what you do not know but wish you did, or facts about what you have already tried. Try to generate facts drawing upon many different points of view. A CEO, hourly employee, husband, or wife may often see the same problem from different perspectives. Remember, quantity breeds quality.

Converge: Pick what you think are five to nine key facts about your situation. Again, remember to draw upon different points of view.

STEP 3: Challenge Clarification

Diverge: Look at your key facts and generate a list of challenge statements using “How might we …?” For example: Fact: Our labor cost is $8 per unit. Challenges: How might we reduce our labor cost below $8 per unit? How might we use fewer people? How might we increase our output per person?

Taking any challenge statement and asking “What’s stopping you from …?” or “Why do you want to …?” may yield alternative challenges that you had not considered. This questioning technique is another divergent thinking tool.

Converge: Pick a problem statement or challenge that most clearly states your problem. If you have asked the question, “What’s stopping you from …?”; gotten answers; and then created a new challenge statement, you have identified possible root causes or sub-problems. Identifying these root causes helps to clarify the real challenge. A problem well stated is half solved.

STEP 4: Idea Search

Diverge: List alternative ways to solve the problem you selected. Go for quantity, not quality, and use the guidelines for effective divergence.

Converge: Pick one, or as many as possible, of the best alternatives that will help solve your problem. The number of solutions you pick may vary for each problem you try to solve. If each solution is expensive, you may only pick one to implement. If solutions are not expensive and you have the resources to implement many, then pick the most feasible solutions.

STEP 5: Action Plan

Diverge: Generate a list of action steps necessary to put the idea(s) into use.

Converge: Determine the order in which the action steps must be carried out. Determine who should do each action step and when it will be completed.

STEP 6: Implementing for Success

Implementation may require the use of many diverse tools to push your solutions through the system to be successful. Some of the implementation tools to consider are: determining the project value (in dollars per year); conducting a shareholder analysis to determine who will gain or lose by the implementation of your solutions; developing a selling plan for your solutions—ideas are harder to sell than products or services; developing a tracking system to check and monitor progress; developing a plan on how to reward for success/failure; and anticipating any possible difficulty and proactively planning for any problems when implementing.

Diverge: The skill of divergent thinking can be used with any of the implementation tools listed above. For example: To determine project value, diverge a list of benefits to your solution(s). To determine positive/negative stakeholder, diverge a list of people who will be affected positively or negatively by the implementation of your solution(s).

Converge: The skill of convergence can be used with any of the implementation tools. To determine project value or put any plan together will require the use of logic and judgment.

Note

1These remarks were given as a part of a commencement address for the Babcock Graduate School of Management at Wake Forest University on May 20, 1984.

Drucker, P. (1986). Innovation and entrepreneurship: Practice and principles. New York: Harper & Row.

Mott, P. E. (1972). The characteristics of effective organizations. New York: Harper & Row.

~~~

Dave Morrison is a creativity practitioner. For many years he practiced inside Frito-Lay—an organization where he had a variety of rich experiences that would serve him well both as an internal and external consultant. He is an engineer by training who has invested time attending various creativity training programs provided by the Creative Education Foundation and the Center for Creative Leadership.

Dave had to live creativity within the company, and it was these experiences and his teaching ability that attracted us. We heard him present in other settings, and the message was such that we knew we had to have him for Creativity Week X in 1987. His real-world experience helped provide the balance to the academics who took part.

Eventually Dave served as an adjunct faculty member for the Center’s courses on implementing innovation and effecting change. Today, he is an independent consultant and partner in the consulting firm Involvement Systems, Inc., in Dallas, Texas. SSG and DAH.