5

What You See Is Not What You Get

A delegation from a major Moroccan financial institution was excited to meet with EquiTech (ET), a UK‐headquartered fintech company, to negotiate the terms of their business relationship. ET's advanced technology platform seemed best suited to meet their needs for enhanced security, speed, and reliability of certain financial transactions. They were chosen from among three contenders, including one from France and the other from Germany, whose technology promised similar advantages. What distinguished ET was their customer support—well, supposedly.

Already, after the first day, the Moroccan delegation was ready to pull out. Their executives were incensed at the rude and disrespectful reception by their host. Their conduct and lack of courtesy and attention to their guests did not match the promises of being focused on customer needs. That evening a junior member of the delegation communicated to the ET team how displeased the Moroccan executives were and that they were considering withdrawing from the negotiation.

This news puzzled and surprised the ET team. The conversations had been friendly and pleasant, although a bit less substantive than the team expected. They were prepared, and they presented at great length the specifics of the arrangement, the anticipated updating and upgrading cycles, project implementation plans, and even offered to train their prospective client's staff at no additional cost in order to address gaps in their technical competence. Overall, it was a good day.

The only curious occurrence was the extreme task and business focus of the delegation. Simon, the ET team had expected to start the meeting with a more informal lunch to “break the ice,” establish rapport, and get more personally acquainted before turning to the business at hand. With an empathic comment and question (“You must surely be hungry after this early morning flight. Would you like some lunch?”), he bid the delegation to lunch. However, Simon and his team were very much taken aback when the head of the delegation refused, stating that they were not hungry at all.

Simon tried again about forty‐five minutes later, after his initial presentation to set the stage for the technical reviews to follow, but his offer of lunch was refused again. Simon, together with his increasingly hungry team, was wondering if this refusal was part of a negotiation tactic to negotiate further concessions later on that day. He was perplexed that this prospective client was threatening to withdraw. After all, the technical reviews went very smoothly and his team could answer all the questions and challenges the delegation had raised.

He was worried now. What did they miss? A lot was riding on landing this deal. They were not as big as their competitors, and they invested heavily in developing this opportunity. Landing this deal with this semigovernmental client would bolster their credibility and open up opportunity in fast‐growing markets in the region. A lot was at stake and they had been focused and prepared. Simon was getting anxious and wondering what went wrong.

Robin, a subject matter expert on the ET team mentioned that this threat might very well be a hardball negotiation tactic. She had heard that North African negotiators were shrewd, calculated, and unpredictable. She mused that even though they had seemed very pleased with the technical aspects of the meeting, they might just be setting the stage for a hard‐nosed fee negotiation the next day.

Simon appreciated the comments but found little consolation in them. After all, they had negotiated the fees before and had been very transparent about the cost structure and the impact on margins. Surely, their prospective client could appreciate how slim the margins would be, particularly through the initial startup phases. Then, they also threw in the training at no extra charge, which was a considerable investment of ET time and resources. What else could they want?

The evening conversation on the Moroccan side was very different. The leaders of the delegation, a member of the Royal family among them, were incensed by the disrespect they had experienced. They traveled to make this deal and did not even get the courtesy of lunch! One of them said that he expected nothing less than this disrespectful treatment, as this was to be expected by such cold and insensitive people. “It's typical! Just look at their history!” he exclaimed. Emotions were clearly high.

***

Quantum physics is the science of the invisible (and surprising) aspects and forces that make up reality. Similarly, Quantum Negotiation (and Quantum Leadership) entails being alert and attentive to the seemingly small and invisible aspects that underpin human thinking, feeling, and behavior.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, social and biological studies on the invisible workings of the human brain and human behavior were seen as incompatible. Scientific advances now focus on a synthesized approach across diverse sciences. Quantum physics and social neuroscience both emphasize the connection between the different levels of social and biological domains (for example, molecular, cellular, system‐related, personal, relational, collective, societal, and cultural). Social neuroscience investigates the connection between neural and social processes developed in social psychology, cognitive psychology, and neuropsychology. These approaches are associated with a variety of neurobiological techniques, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), transcranial magnetic stimulation, electrocardiograms, endocrinology, and immunology.

What researchers are learning about the human brain and how it functions has direct application to how Quantum Negotiators learn, and retain what they learn, as well as how implicit associations and unconscious biases affect the process and outcomes of negotiations. In addition, the socially conditioned brain (i.e., the social mind) has been decoded. Neuroscience research has also shown that social learning can be more robust than individual learning. Quantum Negotiators gain clarity on how they learn from their own social conditioning and how this may contrast with the way others have been rewarded as they learned. This knowledge serves as the foundation for effectiveness and helps manage conflicts both at work and in their personal life.

So, how does that help us understand the derailment experienced between the Moroccan delegation and the ET team?

Had both parties been more attentive to the “quanta” in their interaction—the seemingly small and invisible aspects that underpin human thinking, feeling, and behavior—this experience might have unfolded very differently. Both parties failed to factor in the nuances in their respective cultures and prevailing norms that determined expectations and behavior. They lacked awareness of their own and the others' socially conditioned brain. This included the biases and stereotypes that are deeply embedded in our cognitive frames, yet easily evoked and reinforced through stress.

What the ET team failed to comprehend was refusing an offer for lunch was a respectful and polite response from a Moroccan perspective. The expectation was that the host would continue to offer and then cajole the host into accepting the lunch invitation and move to the lunch area. Declining the offer was simply the first step in a polite ritual that would allow the guest to maintain a sense of propriety and modesty while allowing the host to emphatically manifest the best of their intention—their care, concern, and esteem for their guest.

The importance of this “dance” and its implicit meaning in a culture where honor, giving face, and saving face—which means showing respect and avoiding shame and embarrassment—are key drivers for behavior and motivation cannot be underestimated. That lunch was ready and waiting did not make a difference; the insult and lack of sensitivity of the host who left their guest hungry by not being attuned to the interactive intricacies, however, did.

The clash with the expectations and assumptions for the ET team could not be greater. The intricacy and meaning of this dance was simply absent from their more pragmatic frame of reference about lunch and explicit understanding of the answer to the statement “You must be hungry!” In addition, the pushy way of cajoling violated senses of propriety and respect from their cultural perspective.

Most critically though, neither side recognized the nature of these gaps, but fell victim to stereotypes and biases that are deeply anchored in their respective collective unconscious. The attitudinal shifts thus created can have a profound repercussion, change the course of relationships and negotiations profoundly, and undermine even the best of intentions. In this case, a French competitor ended up with the contract. It was the historical connection between the two countries that anchored greater levels of attunement to such relational “quanta.” The lack of insight and astuteness, and sensitivity derailed a mutual‐gains strategy.

The following experience shared by Juliette and Marcus illustrates how they could find mutual gains both at work and at home by reorienting from a self‐focused view to the smallest particles of their shared interests.

Juliette and Marcus had a personal relationship, as well as a partnership in a small business. As Quantum Negotiators, they wanted to use a mutual‐gains process to negotiate at home as well. Their relationship was tested under the stress of competing work demands. Their schedules were in conflict, they both put in long days, and the financial stress of a new business was putting a lot of pressure on them. The rapport and trust that had kept them going in the beginning were deteriorating.

The needs and demands of the business left Marcus and Juliette with little time or energy for themselves or each other. Their feelings of frustration and lack of motivation began to affect their business, their marriage, and their health. The frustration was creating confusion and uncertainty about how to solve challenges in the business. It was also blocking the emotional and physical energy they once brought to the partnership. Increasingly, they were losing clarity about each of their own needs, which had an increasing impact on the business partnership. The more the business relationship became strained, the less personal energy and vitality they had, and vice versa.

As Juliette and Marcus reflected on their emotional, spiritual, and physical dimensions, they began to understand their feelings and behaviors more fully. They became more aware of not only their own emotional needs, but also joint needs of their relationship and business. They discovered that it was necessary not only to advance the interests of the business, but also to have separate identities and boundaries about their individual needs—to be sociocentric, separate but connected. They created a psychological safety for them to share and exchange their deepest needs.

As an introvert, Juliette was easily overwhelmed by the social networking demands of the business. When she understood and accepted her need to recharge her batteries with quiet time and contemplation, Juliette became much more energized and creative, proposing new ideas and plans for the business.

Juliette negotiated for needed quiet time to boost her energy. This time balanced her need for quiet, belief in service, behavior as a partner, and her ability to think more creatively about the business.

Marcus recognized that his need as an extrovert was to spend more time with other people. He negotiated to take over the sales and marketing element of the business. Energized by the social activity of meeting with potential buyers, Marcus knew that he needed activity to recharge his enthusiasm for the business. Both sets of talents that Juliette and Marcus provided were required for the success of their business. Their goal was not to think alike, but to think together. This has become an important tool of their negotiation success. They restructured their business to include and engage the best of their talents and needs.

Smallest Particles of Motivation

Marcus and Juliette's experience illustrates key aspects of human motivation. Research points out that modern humans are motivated less by the classic carrot‐and‐stick approach than by having their emotional needs about choice and self‐actualization engaged. This understanding of how to motivate others is one of the primary Quantum Leadership skills and creates psychological safety for sharing information.

An obstacle for many negotiators who think they need to use coercion is that they are often unaware of how complex their needs really are in a social interaction. As a result, despite all their preparation, they often do not really understand what motivates them to behave the way they do and why a relationship is important to them. Therefore, they have not clarified all the unseen motivations that they have of their own. When clarifying on both the personal and the social needs they have, they can enhance their careers and relationships.

The unseen needs of the relationship helped Marcus and Juliette to negotiate more successfully. Juliette, for example, took the time to think about and to ask Marcus what his emotional, spiritual, and physical needs were. She did not just think she knew what he wanted. Because she had experience and insight from doing this for herself, she had the capability to recognize, validate, and respond to what Marcus needed. This clarity in their understanding of the multiple levels of needs they each had increased their effectiveness in negotiating and supporting each other.

Quantum Negotiators know that humans are largely driven by intrinsic personal rewards and motivations, and not by controlling or coercive forces in partnership dynamics. The classic coercive tradition of making threats does not motivate friends or colleagues very well to comply with requests or demands in relationships. Those who use Quantum Negotiation behaviors are becoming increasingly aware of how and why internal rewards encourage cooperation.

A sociocentric orientation of self‐interest provides the insight necessary to guide powerful leadership in a dialogue versus a debate by engaging, listening, and keeping in mind the interests of both parties. Quantum Leaders do not abandon their own goals for the sake of others, as an altruist would. A sociocentric orientation helps those most powerful to realistically acknowledge that their own and their partner's self‐interests are connected. This encourages nourishing behavior in social interactions, as accepting and listening to a friend can motivate him or her to be more trusting and cooperative in solving problems. Blaming, reprimanding, and invaliding a friend's concerns does not.

Anxious or controlling individuals are unlikely to recognize that the self‐interests of colleagues are in fact compatible. Tragically, then, with too much control they often reject a rich resource of relationships that would help to support life's goals. Quantum Negotiators recognize themselves as autonomous, but still interconnected, in making decisions and fulfilling their life goals.

Quantum Leaders explore the unseen ways that disruption in their external environment affects or causes disruption in their own internal nervous system. By understanding the unseen ways their human brain works under stress, these negotiators gain clarity about the way they think, feel, and behave. Research in brain science can be applied in negotiation preparation by being more conscious about what threatens or makes them anxious.

By embracing the natural human response to fear, they can consciously create a safe climate for shared experiences and ways others can cocreate solutions. The Quantum Preparation framework is a great tool to calm their own anxiety with knowledge about the seen and unseen dimensions of negotiation. This creates less motivation to control others out of fear, but rather to respond in ways to create safe and collaborative relationships.

One of the Quantum Negotiation practices is to explore unseen adaptive, defensive ways that negotiators often fall into under high stress. When it is understood that a fearful reaction can create a disconnection from themselves or others around them, negotiators prepare to be anchored and connected to their own needs and manage their own anxiety first. Without consciously aligning and anchoring their own emotions, body sensations, memories, and senses, it is natural that negotiators would depersonalize others and go on autopilot to control and coerce others without a recognition of any lost value creation.

Quantum Leaders connect and anchor to their surroundings and have clarity about others' perceptions of reality. This anchoring of their own identity and needs prevents confusion, uncertainty, or conflicts when expressing what they need. This anchor is the foundation for their buoyant behavior in stressful, turbulent relationships or circumstances. The conscious practice to explore how their own mind is the source of anxiety, and how it affects their own and others' brain chemistries and connections, instills confidence and patience in others. Preparation in understanding why they might have a racing heartbeat, panic attacks, lightheadedness, and other physical symptoms in the presence of a counterpart can then be managed with more clarity.

Karine's Preparation for Leadership Anxiety

Karine shared a story about how she used the Quantum Preparation framework to manage her own anxiety before taking a leadership position in her career. As a Quantum Negotiator, she knew she needed to manage her own anxiety before she could effectively lead others. Before she went to college she had planned to be engaged with others in the dorms and classes. She knew that the single rooms with long corridors would require her to break her habit of “keeping herself closeted up.” She had a lot of perceptions about her “social anxiety” and preferred to be alone, avoid social conflicts, and to “mind her own business.”

Karine believed that her shyness kept her from engaging with others. She preferred to go to the movies by herself and spend her study and free time alone. However, she wanted to have more fun and learn to be more social and engaging in her freshman year. She had a good friend who encouraged her to take her time, to “trust herself,” and to get comfortable with who she was. He also said she should notice that all the new freshmen had common interests and concerns. This gave her a sense of her connection to her own needs and how to begin engaging with others.

Once she learned to appreciate and connect with her own identity, she became clearer about her goals and the ways her anxiety kept her from connecting with others. First, she learned to accept that she did not like loud parties, music, and alcohol. Then she began to make friends in small groups and she soon found herself more included in the freshman community.

However, she noticed that she could not get what she needed in some groups that were controlling and disrespectful. She would want to say something about the disrespectful way people talked to one another, but she did not feel confident in herself. Karine knew that she would like more leadership positions on campus but was anxious about speaking up. Karine found it was hard to feel satisfied or reach her goals of achieving better social connections and visibility in her first freshman semester because she would avoid all conflict situations.

Her avoidance in speaking up for her needs and for others created more stress for Karine and she was soon excluded from many campus groups. She then sought out an internship at a mental health facility on campus. In her classes and training, she learned mental health practices and tools she could use to help others. By learning new communication skills and ways to advocate for others, she could negotiate for many of her patients with the administration and community centers. By managing her own anxiety and developing her negotiation skills, she felt empowered to make a difference where she had felt avoidant or indifferent before. Today, Karine uses her Quantum leadership and negotiation skills as a clinical mental health counselor, yoga instructor, and expressive dance therapist. Here are just a few of the steps she used to increase her leadership capability:

- Take a more observant look at social relationships and WHO you are in relation to others in that context

- Observe and gain more clarity about WHO others are in your social circles and WHY their behaviors don't necessarily mean they are suspicious or malevolent

- Take responsibility for the choices and feelings of WHY you do not often engage with others

- Explore WHY others have similar interests and needs and WHY relationships can be engaging and supportive

- Consider WHAT IF there is a situation you choose not to engage in, what alternatives and options you do have to disengage

- Prepare for HOW you could connect to others, understand differing perspectives, and lead engagement with them

The Unseen: The Culturally Conditioned Brain

Quantum Negotiation practices are built on what social neuroscience teaches about the human nervous system and what underlies human health and behavior. Humans are fundamentally a social and connected species, rather than isolated “atoms,” to parallel what quantum physics has discovered. Cultural groups evolved with the neural and hormonal connections to support them, and this helped communities, families, and societies survive and grow. The way the human brain develops is dependent on and susceptible to cultural influences and stimulation. Culture becomes the unseen pattern of ideas and emotions that are shared among members of a group and renders their behavior and symbology meaningful and coherent.

Quantum Negotiators explore what they unconsciously learned and how they expect and reward the same cultural behaviors. Deliberate focus on emotional regulation and clarity in thinking assists Quantum Negotiators to optimize their brain function and fitness for the possibility of releasing trust chemicals and building a functional whole‐brain circuitry to perform, problem solve, share limited resources, and to create new things, even under stressful conditions.

Quantum Negotiators are also aware of how to connect with, inspire, and influence others to collaborate and cooperate, by understanding how contagion of either positive or negative dynamics can “infect” a group and influence it's developing (micro‐)culture. The clarity of one's own cultural values, integrity, and presence will have either a positive or negative impact on others' ability to maintain the same. If a Quantum Negotiator has a positive impact and builds strong relationships with his team or counterpart, then they will be able to renegotiate time and time again as their industries, organizations, and markets rapidly change.

The Quantum Negotiation Profile (QNP)

A conclusive body of research points to the detrimental impact of unconscious bias in cultural groups, and organizational and leadership performance. The QNP identifies a negotiator's cultural orientations and flags similarities or gaps with others that can either contribute to undesirable disconnects or desired synergies in relationships. It helps make conscious the unknown attachments, beliefs, and assumptions that have an impact on our success. With this awareness, Quantum Leaders can better navigate these unseen forces through adaptive behaviors and strategies. This practice of cultural competence is at the heart of buoyancy.

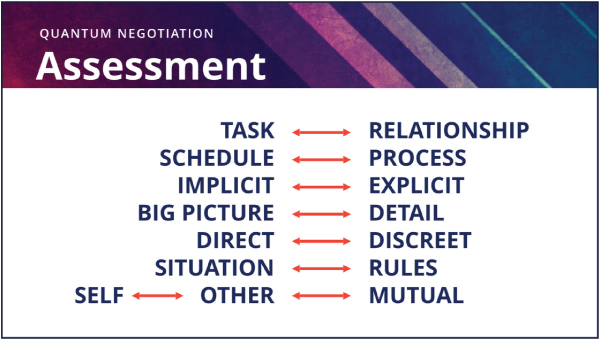

This tool can assist negotiators in understanding the hidden, cultural, conditioned drivers of subjective experience—motivation, beliefs, assumptions, interpretations, and behaviors. It serves as a discovery tool to build the awareness of self and others upon which the successful calibration of one's relationship, leadership, and negotiation behaviors depend. It is based on seven scales of cultural dichotomies that factor, mostly unconsciously and implicitly, into the conditioned calculations and assumptions. Figure 5.1 provides a brief summary for easy reference. Engaging with these scales helps make the unconscious conscious and explicit so that we can use this awareness deliberately to enhance the quality and success of our interactions. To receive training or coaching along with your own Quantum Negotiation Assessment go to www.quantumnegotiation.com.

Figure 5.1 Quantum Negotiation Profile.

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

1. Task–Relationship Centeredness

This scale relates to fundamentally different approaches to problem solving and taking action. See Figure 5.2 for a graphic representation.

Figure 5.2 Task–Relationship Scale

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

A task‐centered approach is characterized by a focus on the essential issue to address or problem to solve, and attempts to pursue the most direct path of action to accomplishing a specific outcome. This approach prioritizes the most efficient way of getting things done. In contrast, a relationship‐centered approach focuses on the relationships that surround the issue or problem and are involved in achieving a specific outcome. This approach prioritizes the building of trusting relationships as a foundation to getting things done. From a relationship‐centered perspective, relationships cannot be separated from the task at hand. From a task‐centered perspective, relationships are secondary and subordinated to the task at hand, often more discretionary than mandatory.

These differences have a powerful impact on negotiation behaviors, even on the very definition of negotiation itself. Do we understand a negotiation as a transaction, or a deal, that is primarily achieved at the bargaining table? Or is it a relationship and therefore requires the careful orchestration of a relationship? Interculturally, the understanding of and approaches to negotiation reflect this difference. In relationship‐oriented cultures, bargaining—which is often deemed to be the essence of negotiation in task‐oriented cultures—is but a part of the overall negotiation process that is nestled within carefully orchestrated relationship strategies that can seem entirely nonessential to the task‐oriented negotiator.

For example, when Jose from southern Mexico began working in the United States in New York, he felt uncomfortable with getting right to the task at the beginning of meetings. He was more comfortable from his background to spend a lot of time at the beginning of meetings to discuss family and weekend events. There was more of a focus on the task rather than on the relationship and he learned to regard this as not better or worse, but different from what he was used to.

2. Schedule–Process Focus

This scale is related to how negotiators relate to and use time. It distinguishes two fundamentally different foci that define how we orient ourselves toward time. See Figure 5.3 for a graphic representation.

Figure 5.3 Schedule–Process Scale

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

A schedule‐focused approach values detailed planning, schedules, and timelines, and values their adherence. They value punctuality and feel that time commitments are fixed, unchangeable, and that agreed-upon schedules determine actions. In this approach, time is an independent variable. A process‐focused approach is comfortable with an unfolding and ambiguous process that requires responsiveness and adjustment. In this approach, time is a dependent variable. Schedules, timelines, and time‐bound commitments may shift and adjust in light of new requirements and information impacting the evolving process.

Negotiations are inherently dynamic and uncertain, but the need to exert control over them through schedules can create a sense of certainty and urgency into the process. As such, schedule orientations are more correlated with task‐oriented negotiation approaches, whereas a process focus is commensurate with a relationship‐based understanding of and approach to negotiation.

3. Implicit–Explicit Communication

This scale refers two different orientations toward communication, specifically how we encode, decode, and exchange meaning. Figure 5.4 provides a graphic depiction.

Figure 5.4 Implicit–Explicit Scale

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

An implicit approach to communication is likely to value metaphoric, artful communication, including indirect references, understatements, humor, as well as nonverbal (intonation, facial expressions, etc.) and extraverbal (settings, use of space, gift giving, and other symbolism) ways of conveying meaning. Implicit communicators expect and scan for hidden meanings within communication. This tendency can easily clash with explicit communicators who generally rely on words for meaning, verbal or in writing, and discount the importance or significance of nonverbal and extraverbal aspects of communication.

In any communication, including negotiations, implicit and explicit aspects coexist. As contexts evolve, conventions and norms dictate the reliance on more or less explicit approaches. Formal negotiations are often expected to result in a contract, which gives expression to mutual expectations, obligations, and entitlements of each party explicitly in writing, and ratified through signatures. The process of arriving at a written contract, however, often starts in more implicit ways. Of course, an agreement more often takes the form of a confirmatory e-mail, an emoji, a handshake, an “OK” gesture, a thumbs‐up, a head nod, shared clapping, participation in a prescribed ritual or rite of passage, a meal together, a simple toast, or conforming with set rules and norms. These signals of implicit agreements and understanding among parties are the results of a negotiation process that was never perceived or labeled as such. The degree to which we resort to explicit forms of agreement is often a function of existing trust, perceived risk, and complexity of an agreement, such as the number of stakeholders, or the size, scope, and significance of the agreement.

4. Big Picture–Detail Orientation

This scale refers to different cognitive approaches and uses of logic and argumentation. Figure 5.5 provides a graphic representation of these key cognitive styles.

Figure 5.5 Big Picture–Detail Scale

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

A big picture–oriented approach focuses first on the larger context of a situation/task. With this approach, there is an individual focus on agreement on general frameworks and principles that will then, by inference and extension, also apply to the specifics of a given problem or situation. They are likely to think broadly and generally, looking at the interdependency and patterns between variables, and focus on their complex relationships. This contrasts with a detail‐oriented approach, which focuses on the specifics of a given situation or problem, isolating the specific variables of significance. Negotiators leave the surrounding context and interrelated variables out of scope and narrow in on the precise aspects under investigation or negotiation.

We can discern vastly differing approaches to negotiations between those oriented toward the big picture and those oriented toward details. The types of questions asked early in a process provide cues about the preferred approach of one's counterparts, for example. Does she raise questions regarding the context or features of a specific solution to be agreed upon? Does she notice features or frames? Does she notice the setting in which interactions take place or is she focused just on the discussion?

5. Direct–Discreet Conflict Handling

The scale relates to different styles for handling conflict. Figure 5.6 provides a graphic representation of the key differences.

Figure 5.6 Direct–Discreet Scale

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

A direct conflict‐handling style is likely to be open and straightforward in conflict situations. Direct conflict handlers speak their mind openly and may not be worried about the impact on others, assuming that honesty about thoughts and feelings is of primary value to a relationship. Direct approaches can vary significantly in their “emotional loading,” that is, the degree to which emotional expression is considered an important aspect of the valued honesty. By contrast, discreet conflict‐handling approaches are likely to prioritize face‐saving and the appearance of harmony, honor, and respect throughout conflict situations. This is accomplished by suppressing open discord and resorting to more indirect modes of communication in conflict situations, such as the use of intermediaries, as well as the use of allegories or understatements and implicit communication (see earlier discussion). Discreet conflict handlers tend to withhold and guard their true thoughts and feelings in conflict situations.

Negotiations and communications always entail a form of disagreement, friction, or conflict and the act of resolving them to the satisfaction of all stakeholders. Hence, conflict‐handling approaches are integral to negotiations. Sensitivity to and compatibility of conflict approaches among stakeholders are significant factors in success.

6. Situation‐ and Rule‐Based Approaches

This scale refers to differences in criteria that guide decision making. Figure 5.7 graphically depicts these different approaches.

Figure 5.7 Situation–Rule Scale

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

Situation‐based approaches tend to be highly pragmatic and variable, depending on the specific situations encountered and their constituent variables. By contrast, rule‐based approaches tend to set or adhere to specific rules that govern decision making regardless of specific situations. When confronted with a rule, a situation‐based approach is likely to reinterpret the rule, feel it needs to be adjusted to the situation, or ignore it altogether, if it seems too broad and general.

For a process‐based approach, it is likely that negotiators want to adapt their behavior based on the situation. They may feel that rules should be adjusted to better suit a situation. A rule‐based approach is likely to regard rules as binding independent of a situation, and it abides by rules, processes, and regulations as the guidelines of behaviors and choices. For rule‐based individuals, rules provide consistency and the understanding of expectations.

This difference affects negotiations in a significant way as the very principle of negotiability may be perceived differently through the differing lenses of situation‐ and rule‐based approaches. From a rule‐based perspective, rules are nonnegotiable. They are the very foundation for reliability and trust, and govern formal and informal, explicit and implicit agreements. From a situation‐based perspective, however, rules themselves are subject to interpretation and negotiation as a situation‐based approach can precluded the acceptance of a seemingly general and abstract set of rules in circumstances that may make the rules appear meaningless or irrelevant.

This also extends to the understanding and “binding” nature of a written contract. It is common for many businesspeople to experience surprise, when upon the completion of contract negotiation in countries with a more situation‐based approach, the counterpart continues the negotiation even after a formal contract with clear terms, conditions, and rules has been signed. This behavior makes perfect sense from a situation‐based lens, particularly if circumstances and conditions around the agreements have shifted.

7. Self‐, Other‐, or Mutuality Focus

This dimension does not parallel the other scales as it depicts three fundamentally different interests that drive decision making and understanding of gain and motivation. Figure 5.8 provides a graphic depiction of these three approaches.

Figure 5.8 Self‐Other‐Mutuality Scale

©2015 Quantum Negotiation

A self‐focused approach prioritizes the pursuit of individual interests and needs. It assumes that maximization of gain and furthering of self‐interest are the most common, natural or desirable motivations in the interactions and exchanges between people. Self‐focused approaches tend to value independence and self‐reliance, and approach negotiation with a sense of more or less adversarial competitiveness. It is often in this competitive assumption where the respect is earned through particularly skillful, sometimes cunning, tactics. By contrast, an other‐focus approach focuses on furthering the interest of a counterpart's interests as a way of harnessing value. The success of this approach relies on the assumption of reciprocity. By furthering another's goals and well‐being, the other is or becomes equally motivated. This approach tends to value dependence and obligatory exchange among interacting agents.

A mutuality‐focused approach is focused, from the onset, on mutual benefits and opportunities. This approach is based on the recognition of interdependence among the parties in an exchange. It recognizes the self‐interests of each while also recognizing and respecting the needs and interests of the other. They value interdependent relationships that further all stakeholders' interests and well‐being, for as long as mutual value and win‐win outcomes can be sustained.

The relevance of this scale to negotiation and leadership is obvious. Negotiations, whether formal or informal, tend to work best when the parties involved share an assumption about how interest is pursued. The competitive nature of self‐focused approaches, when shared between stakeholders, can be quite complementary and yield mutually satisfactory outcomes. But when matched with the other approaches, the result may be distrust and disrespect, and lead to misunderstanding and disappointment as a result.

These scales indicate some measure of difference for understanding and approaching negotiations. They characterize individual preferences in the workplace, as well as organizational and socially enshrined beliefs and norms that can either enable or derail success. Quantum Negotiators and Leaders not only understand these differences and their international and intercultural contexts on individual, group, and organization levels, but they also apply their understanding in practical terms. A Quantum Negotiator's competence relies on the practice of meta‐skills, which we have identified and defined as:

Cultural Due Diligence: This is the habit of assessing cultural similarities and differences and anticipating their potential (desirable and undesirable) impact. This can be done by inviting into the planning process people familiar with the cultures involved and who can provide comparative insights. Studies and tools can also provide useful comparisons, as well as specifically commissioned cultural diagnostics or cross‐cultural, due‐diligence assessments. The latter is particularly recommended when large ventures and transactions are at play, such as joint ventures, mergers, or acquisitions. The Quantum Negotiation Profile also provides a useful framework to organize comparative assessments.

Frame shifting (also: perspective taking): This is the ability to understand the perspective, worldview, and experiences of others from their vantage point and with their frame of reference. While cultural due diligence is typically a rather more clinical and objectified undertaking, frame shifting adds the important subjective, psychological, and emotional dimension to our understanding of differences. This skill requires empathy and emotional intelligence.

Without frame shifting, cultural due diligence is insufficient, as it does not make accessible the all‐important human dimension in our trans‐ and interaction. Through our intercultural work, we are convinced that the high failure rate of organizational transformations and cultural integrations (as in post‐merger & acquisition) are due to either the absence of cultural due diligence or the reliance of a purely clinical, objectified comparison. Seriously factoring the subjective experiences and perspectives of all parties involved into our planning and relationship strategies enables surprising results, even breakthroughs.

Style‐shifting (or style agility): This is the ability to translate insights and understanding of cultural differences into adaptive behaviors. Doing so requires a broad and flexible cognitive and behavioral repertoire. Style‐shifting is immanently learnable, but requires self‐awareness and deliberate practice of behaviors and approaches (and associated beliefs) that expand our culturally conditioned comfort zone. Style-shifting is not only an individual skill, but also a capability of teams and groups in order to navigate differences and/or adapt to shifting requirements and circumstances.

We have developed the Quantum Negotiation Profile as a self‐assessment tool to ground the development of style-shifting. The results alert the Quantum Negotiator to the invisible and unseen forces that have an impact on success. The results indicate an individual's “range,” that is, the part of the scale that defines the individual's comfort zone and beyond which she or he may have blind spots. A narrow range indicates a lack of flexibility and understanding of other approaches, whereas a wide range indicates the opposite.

However, in most cases the development of style‐shifting will require working with a coach over a period of time, and preferably embedded in the specific leadership and negotiation contexts to build this skill effectively.

Cultural dialogue: This is the ability to engage stakeholders in an exploration of their differences in order to negotiate mutual adaptations and alignment. This is a form of meta‐negotiation upon which the success of the nominal negotiation can critically depend. Cultural dialogue requires facilitation skills that are informed by adequate cultural due diligence and perspective taking. It is particularly recommended when it is not clear or cannot be assumed which stakeholder readily assumes the responsibility to adapt to the other or where the pressure to adapt creates experiences that generate resentments and/or resistance, which can easily undermine a given undertaking. This is particularly relevant for highly diverse and heterogeneous teams that need to establish norms that enable effective teamwork and collaboration.

Cultural mentoring: This is the proactive use of cultural insights and understanding to help others navigate them effectively, so that they can become effective participants in the cultural context. Cultural mentoring makes the implicit (unwritten rules, expectations, and norms) explicit and therefore accessible to those unfamiliar with them. As such, it is integral to effective on‐boarding and integration into a new culture and/or context and creates the conditions for effective transactions, interactions, and relationships.

Cultural mentoring in particular is also critical to relieve the awkward tension and discomfort that often accompanies intercultural differences and the ambiguity and uncertainty they create. This is also where humor and playfulness can play an important role, because of their humanizing effect, as discussed in Chapter 1. Particularly when style differences create mixed signals, miscommunication, judgments, and intolerance about others, they can powerfully—and as shown in Chapter 1—memorably release and transform tension. The following case illustrates this effect.

At S. Marten Company's last senior leadership team meeting, Benjamin took several minutes to introduce the newest member, Kim Park, to the group.

Benjamin said, “I expect and reward ‘telling it like it is’ … we value speaking up here if we disagree. Isn't that right, Charlotte?”

Charlotte noticed Kim's face as if he had a question mark on his forehead as she tried to explain what Benjamin meant.

Charlotte stumbled, “Yes, that's correct, Benjamin, you like to be direct and reinforce this kind of communication in our team. That is correct.”

“Mr. Park,” Benjamin emphasized, “we value open discussion and resolution of all disagreements in our discussions. We handle them in an impersonal and objective way. We always get quick results this way.”

“Conflict is positive and constructive here even when tensions are high,” concluded Benjamin. “We are honest and trustworthy here—full transparency…we love it.”

As Charlotte observed the room, she noticed a shock of resentment and annoyance rise deep from inside. She was getting tired of what she felt was “Benjamin's endless embarrassing, insulting, insensitive, and incompetent” way of representing the leadership team to their first Asian member.

In her earlier conversations with Kim, she sensed that he had a less critical and challenging attitude about differences. Charlotte was excited to get some new ideas and practical perspective about the growth in their South Korean markets. She felt fatigued and even depressed that Benjamin's open conflict approach in their leadership meetings would squeeze out Kim's more “civil” and sensitive tone.

Charlotte surprised herself when she blurted out, “Don't worry Kim. We DO have some emotional and social intelligence in this team… Benjamin's just negative. The rest of us have a sense of dignity and integrity and don't need to openly display our disturbing thoughts.”

Benjamin jumped in, “Kim, you don't have to worry that we're all weak, evasive, and suspicious about what we want around here … Charlotte, is a minority.”

“What?” Charlotte exclaimed as she stood up from her chair and walked toward the door… the room fell silent.

Charlotte closed her eyes as she stopped with her hand on the door, and felt her shoulders drop. She took a deep breath, and began to laugh as she turned around to look at Benjamin's ashen face. She laughed again and said they should all take a deep breath. “Where did all this come from?” she exclaimed. “This really is a playful competition, but I forget that, like today!”

“I'm sorry, I'm trying so hard to be less anxious about expressing our concerns in such a public way,” Charlotte said. “This is crazy and we don't mean any of this.” You are really the most good‐natured person I know… and you know how to get me into a frenzy.”

Benjamin chuckled, “I have been trying to watch myself with this directness and ‘skipped the curb’—I know how annoyed I am about avoiding our disagreements. It's hilarious how we clash on this so often—even while trying not to be so thoughtless. I am actually working on not being too critical in our meetings and I don't want to embarrass anyone. I really don't. Charlotte, catch me on it quicker and we can figure out the best way to respect our approaches.”

Charlotte said, “Next time I won't storm out, but will pull my scarf over my head to remind you, Benjamin, that I'm uncomfortable with your directness. Welcome, Kim, to our creative leadership circle playground, unleashing creativity has never been more fun….”

Kim exclaimed, “I will never forget this introduction and your commitment to real innovation and energy.”

Summary

Just like quantum physics is the science of the invisible (and surprising) aspects and forces that make up reality, Quantum Negotiation (and Quantum Leadership) entails being alert and attentive to the seemingly small and invisible aspects that underpin human thinking, feeling, and behavior. There is much for Quantum Leaders to apply from the emerging insights of neuroscience and the connections between the social, psychological, cultural, and emotional aspects of human behavior. The Quantum approach integrates what we know about negotiation with knowledge of intercultural dimensions and neuroscience.

The Quantum Negotiation Profile offers a practical framework for discovery, awareness building, and skill development as part of the essential preparation. It is a tool that provides insights that help us support individuals in their development of quantum skills, encouraging them to become active observers of others and to develop behaviors and skills that are inclusive when working with individuals with differing approaches. The strategic skills and capabilities of cultural due diligence, frame shifting, style-shifting, cultural dialogue, and cultural mentoring can be developed and supported by the Quantum Negotiation Profile in practical and tangible ways.