This chapter looks at the way IT project teams are structured within an organisation. We will cover the different team environments in which project managers work and the people with whom project managers work.

By the end of this chapter you will understand common team structures and the common roles that make up project teams.

COMMON TEAM STRUCTURES

The organisational structure of a company influences how you manage your project and the culture and environment you operate in. It also makes a difference to the amount of authority you have in your role.

There are three common organisational and team structures that you’ll find in project environments: functional, project and matrix. As a project manager, you could work in any or all of these over your career.

Functional

A functional structure is one where the work is contained within a single department. In the IT arena, this could be a switch upgrade at the data centre which has no impact on other teams within the business. A project manager within a functional structure has the least authority over the resources involved in doing the work – they will report to their line managers as normal.

Functional structures have plenty of advantages: it’s easy to get hold of the subject matter experts as they work in the same division as you, and conflicts can be resolved by going up the line as everyone reports into the same leadership team.

Projects run in a functional way within a department tend to have simple communication lines. If you hit a problem it’s easy enough to resolve them with the skills you have in the group. This kind of project is a fantastic development opportunity for members of the department so you’ll often have enthusiastic team members who want to learn. It’s also a lot easier to hand over the deliverables at the end of the project, because the department is both the delivery team and the receiving team.

However, as with all team structures, there are disadvantages to working this way, not least in terms of keeping focus on the goals when there is strong loyalty to the department or functional team. When the department needs to focus on the next crisis or business-as-usual activity, you can find your project resources pulled off on to other work.

You sometimes find that silos are worse in functional teams than they are in project teams deliberately made up of cross-functional representatives. Individuals can be isolated, or make themselves isolated, and you have a job to do to ensure knowledge sharing and transfer within the team.

Finally, a challenge for functionally run projects is that they can suffer from lack of sponsorship and senior leadership. As the project is being run in the department, the leadership team may feel as if they don’t need to appoint a specific sponsor for the initiative. That can cause problems when there are decisions to be made or when someone needs to take ultimate responsibility for the work that is being done.

Project

Project structures are those where the team is put together specifically to work on a project. This can mean taking people out of their day job on secondment for a fixed period. The team is made up of dedicated resources. You’ll only find this on large projects where the workload means there is enough to do in a full-time role.

The main benefit of this is that there is no day job for the team members, so no conflict of interest back to their original team. As the project manager, you are ultimately in charge of the team and the people, so you have full authority over the way the project is managed. You can build a strong sense of project culture and create your own team identity.

It’s an easier job to keep people focused on the goal and you’ll often find people working on the team become passionate about delivery and keen to learn more about how to make the project a success.

Having said that, there are also disadvantages. The cost of a dedicated team can be prohibitive for all but the largest and most strategically significant projects. If you are pulling functional experts out of their day jobs to work on the project, they may find that they lose some of their core functional skills, making it harder to transition back to their normal roles once the project is completed. They may not even want to go back – and then you’ve got an issue with retaining hard-won organisational knowledge in the business.

The team can become inward-looking and isolated in outlook because they are solely focused on one project. If you tie up your best resources in this way it makes it hard to progress other projects at the same time because you might not have the skills you need in other people.

Finally, the project manager takes on a line management responsibility. Some project managers will love the opportunity to learn about line management and to develop this skill, as it can be an incredibly valuable experience. Some project managers will not want to be responsible for managing sickness absence, authorising holiday, processing expense claims and other such activities.

Matrix structures are common in project-led environments. They are made up of individuals representing different departments and different areas of expertise so you end up with a project team that is truly cross-functional and cross-business. Individuals in the team might have responsibilities to several areas: one main line manager and then a ‘dotted line’ into another manager or the project manager.

This structure is so common because responsibilities at work, especially in small and fast-moving businesses, can’t be linear and compartmentalised any longer. There are too many overlaps between professional roles. For example, someone with a ‘digital marketing manager’ job title might find themselves working within the marketing function, but with close ties to the sales team, the internal communications team to ensure the staff intranet is using the same brand assets as consumer-facing websites, and IT for all the digital back-end requirements. Companies organised along process lines or the customer journey will also find themselves running projects in a matrix environment.

If it sounds complicated, it can be, but being able to work in this environment is a core skill for a project manager. At the simplest level, your line manager might be the PMO manager, but your project sponsor could be someone in the finance team. That’s a matrix structure where you have split responsibilities between your two leadership figures.

Matrix organisations can be an efficient way to use the company’s resources. Subject matter experts can work on several projects at a time, and if you need someone from a different department they can easily slot into your team on a matrix basis. There’s a lot of flexibility with how resources are deployed and it should mean that you can pick the best person for the job every time.

Matrix teams rely on consistent ways of working in order to be successful, so it’s a good way to embed best practice. You can’t have subject matter experts working on two projects and each project manager following a slightly different methodology. It would be too confusing, and it doesn’t allow for standardised project reporting that allows for comparability between projects.

However, there are complexities of working like this, as you would expect. The major drawback is that conflict is common. Not the kind where people argue in the corridors (although that can happen too), but conflict between projects and their other responsibilities. Whose project takes priority when they both have upcoming deadlines? And what about the work the individual has to do for their line manager? It can be easy to make people feel overloaded and feel that they have to choose, whereas the project manager and their functional manager should be able to work together to identify clear priorities and schedules for the work.

Conflict can also appear in more subtle ways too, notably where functional managers ring-fence their best resources and refuse to let them work on projects. While in theory you should be able to secure the best person for the job, in reality you may not be able to get a particular individual to work on the team because of their other responsibilities and priorities. When you get a different person – perhaps someone with less experience or lower levels of skill – that can significantly impact your plans. You might need to train them (and that costs time and money). You might have to adapt your schedule because they don’t work as quickly as a more experienced person. This can make for a difficult conversation with your project sponsor: all resources are not created equal in planning terms.

Generally, the advantages of matrix organisation structures outweigh the disadvantages for projects. Once you are aware of the challenges you can work to address them.

Although it’s easy to pigeonhole organisations into running their projects in one of these three structures, bear in mind that organisations are more fluid than this in real life. In most workplaces there’s a continuum of authority and structure on a project that looks more like Figure 3.1.

In structures where the line manager has the most authority over the resources and the project, the project manager has a less significant position in the team. Your negotiation skills become increasingly relevant as you look to secure resources. As you move further to the other end of the continuum, the project manager has more influence over the team and can adopt a more directive leadership style if that’s appropriate for your workplace culture. Your project team will fall somewhere along this continuum and that will shape your role as project manager and the structure of the team.

![]()

IT departments come in all shapes and sizes, and so do IT projects. Here Sarah Johnson, Project Management Consultant, explains her experiences in two very different environments.

I was a programme director at a very small non-profit, though in all honesty my real job was being a project manager for our education, IT and marketing departments. In that role, and my previous non-profit project management role, I was largely self-taught through books, online forums and through taking PMI certification courses at a local university.

I simply didn’t have anyone else I worked with who was from the project management field. My employers didn’t provide any real structure around any of their projects and I was basically given full authority to decide how and when I put forth my new project management skills with no one knowing any better if I was actually doing the project management correctly or not! My typical day was split between doing operations for the non-profit and doing project management for various departments. Some projects spanned a few months; most of the projects were between one and two years in length.

Fast forward to my present job as a project management consultant where I’m based within an insurance company. My boss here has her PMP® along with many of the staff that I work with. Our Project Management Office has about eight dedicated project managers and business analysts building out a $15 million web portal for the company. There is structure, guidance, expectations and rules explained for how project management is done here and why it is done that way. It’s basically the complete opposite of what I came from in many ways.

I like structure and being around fellow project managers that understand project management, so I really enjoy this position. And it doesn’t hurt that I have better hours, benefits and pay than I had in the non-profit sector! My typical day here is 100 per cent project management with a sprinkling of admin work thrown in.

Sarah Johnson, USA, financial services

INTERFACE AND DEPENDENCIES

The role of project manager interacts with other roles in lots of ways. Some of these will be internal, such as your line manager, project sponsor, subject matter experts and others. Some will be external, such as suppliers, government agencies or regulatory bodies.

Common interfaces for a project manager are listed in Figure 3.2 and there’s more detail on the important interfaces below, starting with the most important working relationship that a project manager has: that with the project sponsor.

Your most important relationship: the project sponsor

All projects should have a project sponsor, and this person is normally already in post by the time you are asked to manage the project.8 If you are asked to manage a project and there isn’t a project sponsor in post, you should seriously question the organisation’s commitment to the project. While it might not be appropriate to refuse to work on it, you should certainly flag not having a sponsor as a major risk for the project.

The project sponsor is often a senior leader or director in the department which is going to be most affected by the project. You don’t often (or ever) get to choose your project sponsor so you have to work with who you get. Here are seven things that your project sponsor should be doing for you to ensure the success of the project.

1. Securing resources

Securing resources is the first thing most project managers think of when they consider what a sponsor can do for them. That’s because most of the project team members will come from the project sponsor’s department – if they are the person who benefits most from the project then you would expect the subject matter experts to be based in their teams. That should make securing people for your project team relatively easy. If the sponsor believes it is an important project, he or she will jiggle around the work responsibilities and make it possible for the right people to have enough time to spend on the project.

However, there are also bound to be resources required that fall outside of the sponsor’s team. These people might work for central services such as other areas of IT, HR, marketing or finance and this is where your project sponsor’s negotiation skills come into play. The sponsor may rely on you to identify the kind of person you need on the team and for how long, and then they can go off armed with that information and talk to their peers about ‘borrowing’ that person for the project.

If your sponsor doesn’t have the influence to get you the right people on the team then it’s likely that your project will struggle. You may have to use your leadership and negotiation skills to talk to them honestly about asking someone else for help to secure the right resources.

2. Securing budget

Alongside securing people for the project team, the sponsor also has a critical role to play in securing the budget to manage your project. Again, if it is their budget that is funding the work, and they believe in the project, it should be relatively easy for them to put some of their cash aside for this initiative.

It gets harder when they need to rely on funding from other departments, which happens more often than you think. Despite it being all company money at the end of the day, there are often turf wars between departments trying to protect their own budgets. Project managers can get caught in the middle. You should be able to rely on your sponsor to sort out organisational politics and get you adequate funding.

Project sponsors are also important when it comes to budget and financial management. They are the people who approve additional spending, grant you authority to take money from the contingency fund or management reserves and they may have to authorise large invoices or purchase orders themselves.

If your sponsor doesn’t have the authority to secure or approve funding, then your project will find it difficult to complete all the specified work: without the money you won’t be able to get everything done. You’ll need to talk to them about how to fund the work if they can’t give you budgetary authority.

One of the technical skills relating to project management practice is change control. This is a formal process for assessing any change requests, evaluating the impact on the project and putting forward a recommendation for whether the change should go ahead or not. This includes such information as how long it will take to do the work, the impact of this on the project plan, whether you have the resources to do it and how much it will cost.

This recommendation then goes to the project sponsor who will have the final say over whether the change should be incorporated into the project. It may involve them having to find additional funding or amending their expectations of when the work can be completed.

The decision about whether or not to go ahead with a change may be taken in a formal meeting such as the project board (more on the role of that group below) and may be discussed with the whole group before a decision is made. Or you may find yourself giving your sponsor an overview of the situation and what you would do if it was you while you are in the lunch queue together or waiting for the kettle to boil. Either way, the sponsor formally has the final say about whether a change is incorporated and they should feel comfortable making these decisions.

If your sponsor does not feel that they can act on (or reject) your recommendations when it comes to changes then you’ll find nothing gets approved and the project does not move forward. Think about why this happens – it could be lack of confidence on their part or you might not be giving them the information they need to make a decision.

4. Communicating

Your project sponsor won’t do all the communication on the project – a lot of that will fall to you in the role of project manager. But they should be communicating regularly to their peers, and upwards to their own managers. They should be explaining progress, getting help with any issues they cannot unstick themselves and generally championing the project.

Communication is important because it helps win over stakeholders who might be less than enthusiastic about the changes that the project is bringing in. It also raises the profile of the work which in turn helps with securing resources and budgets.

If your sponsor won’t or can’t communicate then your project will suffer from having a low profile. In turn that has an implication for the priority of your work and the amount of resources you receive to do the work. Talk to your sponsor about what you expect them to do in this area and provide the material to help them champion your project. They might not realise that this forms part of their brief.

5. Motivating the team

Another major part of project sponsorship is motivating the project team. That starts at the very beginning by setting appropriate goals for the project and explaining how the work of the team links back to achieving the strategic objectives of the company. They should be able to set a vision for the project and help everyone see how that will be achieved and what will be different once you reach your goals. They can use motivational stories and share customer experiences. In short, it’s their job to create a positive environment where everyone knows what they should be doing and why. As the project manager, you can carry this on day to day, but the initial guidance should come from the sponsor.

Another way to keep the team morale high is to celebrate successes, and your sponsor can be involved in that too. Whether it is a quick thank you at the end of the week or stumping up the cash for a full-blown post-project party, celebrating success should definitely be on the agenda.

If your sponsor isn’t interested in what the team is doing or in helping them achieve it then you may struggle to keep your team motivated during tough times on the project. You should feel as if you can turn to your sponsor for advice at any time.

Project managers need decisions made. You have a lot of responsibility in your role, bounded by the tolerances and sphere of control set at the beginning of the project, and you can make a lot of decisions alone. However, that responsibility does end somewhere and where it ends is where the sponsor’s responsibility takes over. They should be able to make decisions that help you move the project forward, such as whether or not something should be in scope, what approach you take to dealing with an issue and how much risk they are prepared to accept.

Without such decisions, you’ll be left either having to make them yourself which is really out of your area of authority, or you’ll be stuck in a project that won’t progress because no one will decide what should happen next.

If your project sponsor won’t make decisions you are facing the very real possibility that your project will stop and ultimately fail. Think about why they are struggling to make decisions: are they missing critical information? Do they feel they need input from someone else? It could also be that they simply don’t understand the consequences that failing to make a decision will have, and you should be in a position to explain that.

7. Managing risk

Finally, project sponsors should be managing risk. The day-to-day risk management process falls to you as the project manager, but the sponsor also has a critical role to play. They need to decide how much risk they are prepared to take on the project: too much risk and they put the investment in jeopardy. Too little risk and they restrict the project so much that the rewards become so little it’s not worth doing the project at all.

Your project sponsor should let you know the sort of risk and the amount of risk that they are prepared to take – their personal risk tolerance and that of the company. This will help you manage the day-to-day risks appropriately and bring anything necessary to their attention.

A project sponsor who fails to understand risk management may end up creating more problems for the project, so if your sponsor doesn’t seem to ‘get’ it, invite them to some risk management meetings and keep talking to them about it.

Project sponsors are essential people on the team, and great assets when they do what you need them to! Project sponsors who aren’t engaged are difficult to work with and contribute to making the project harder than it really needs to be.

Project team members (subject matter experts)

‘Project team members’ is a very general term for the people working with you on the project, but it normally refers to the people who have a significant role to play in the project’s successful completion. These are your core team: the people involved from start to finish and whom you couldn’t do without.

The exact make up of this group is going to differ with every project but they are the experts who bring something unique to the team. They have the depth and breadth of knowledge required to complete the tasks and they’ll have input into how the work is scheduled and done. Examples include:

- data analyst;

- system architect;

- database systems administrator;

- platform engineer;

- telephony engineer;

- network engineer;

- applications specialist;

- technical sales manager;

- development team member;

- software tester;

- scrum master.

You’ll probably have at least one subject matter expert who represents the area of the business affected by the change, who is known as the ‘Product Owner’ in a Scrum team. This person can help define the requirements, explain how the project will affect their team and represent the ‘customer’. The customer could be an internal department or an external group like a member of the public using your new app.

Subject matter experts can pitch in and help with so many areas of the project from testing to training and communicating back to their colleagues.

Department managers

Heads of department and team leaders are not people with a direct role to play on the project in that they don’t do any of the tasks, but their staff are your project team members.

You’ll have a relationship with them because you’ll be working with them to secure the time you need from their staff. You’ll also need to get them involved in setting priorities because they’ll need to allow those people enough time to do their project work. If they consider the functional job to be more important, you will struggle to get their team members to commit to their project tasks.

Project governance roles

Within your project environment, certain roles have a governance function to play: these are all about monitoring and controlling the project’s performance and ensuring it operates within the boundaries and policies set by the organisation. The governance roles typically are:

- The project sponsor: An individual with ultimate responsibility for the success of the project. It’s normally the senior manager who holds the budget or resources and may receive the benefit of the project. For example, if you’re delivering a new system for online invoice payment, the project sponsor would be a senior manager within the finance system with responsibility for accounts receivable, so their team would be using the system when it goes live. There’s more on the role of the project sponsor and how to work effectively with them earlier in this chapter.

- The project board: A group of people who form the decision-making body on the project. This will include the project manager, the project sponsor (representing the users), the key supplier if you have a major contractor on the project, and other senior managers who hold particular influence over the resources, budget or success of the project. This group might also be called a ‘steering group’.

- There may also be a level of governance above the project board. This is often formed of a sub-set of the executive directors and oversees the strategic implications of the project. The project manager may not attend these meetings; the project sponsor may represent the project. Whether or not you have a group like this will depend on the hierarchical make up of your organisation and the nature of your project. The more significant, complex or business critical your project, the more likely it is that you will have top level oversight in some form.

- The project management office: PMOs come in all shapes and sizes, and can play a governance function on your project. They also have a lot of names: yours might be called a programme office, an enterprise PMO or a project support office. Whatever the name, this team provides support to project managers and collects, consolidates and reports on project information. They are also the guardians of project management standards, templates, methodologies and tools within the organisation so you will find them heavily involved in process compliance. Your PMO may also be responsible for business assurance: making sure that the project remains viable and is on track to deliver the expected benefits, although your project board may carry out this role. PMOs can do a lot more than what’s listed here, but they all have a function around ensuring projects succeed, and governance is a large part of that.

- Quality assurance: An individual or team with the responsibility for carrying out an independent check on what the project is delivering. The purpose is to assure the organisation that the outputs will be fit for purpose. Quality assurance is carried out by someone outside your project team and they may also look at whether you are following corporate guidelines or standards with regard to what you are delivering.

Business analyst

Whether your project is large or small, as a project manager you will no doubt find yourself working with a business analyst (BA) at some point in your career. A business analyst is a professional with great communication skills who can present complex ideas clearly. They are excellent problem solvers and can analyse difficult situations, and because of this they are an asset on project teams, especially in environments where constant change is the norm.

A business analyst on the project team will help you understand how the project contributes to the company overall and will ensure that you get a high-quality solution that works to achieve strategic and tactical objectives.

The role of a business analyst can vary, from someone who elicits user requirements to someone who contributes at a senior strategic level through portfolio work and assesses solutions before they become projects to ensure the organisation invests sensibly.

A BA has a role to play throughout the project but perhaps most importantly at the beginning. While the project manager is going through the project initiation process, the BA can be working in parallel defining the requirements. They understand the business circumstances that led to this project being kicked off in the first place and they can support the project throughout its life cycle. They can be the voice of the customer when the customer isn’t present, and help translate the customer’s requirements into a project scope that can be effectively delivered.

There’s another key moment where working in tandem becomes even more important than normal: testing. The BA can track whether the requirements have been achieved adequately and advise the customer and project team during the testing phase.

As every organisation expects slightly different things from their BA teams, you will have to agree roles and responsibilities with the individuals.

If you have a business analyst on the project team, make sure that you include all the BA work in your schedule as some of it will have implications for when other tasks can start or when resources are available. Sit down with the BA and establish what their activities will involve, how much time they need to complete them and who they will have to work with. This will help you both avoid resource clashes or delays later.

The BA should attend all relevant project team meetings and be involved in project risk management. They have a deep understanding of the impact of the risk to the business and will also be able to identify risks that others on the team might not be able to see.

They can also get involved with lessons learned meetings as they will probably be the person on the team closest to the business users and with the best understanding of how the project is affecting the business teams.

Scrum Master

Agile is a commonly used approach for managing projects in a software environment, and is increasingly used outside of software development too. There’s more about Agile project management methods in Chapter 4.

In an Agile environment you might be working with a Scrum team (known as the development team, which includes developers and testers) and a Scrum Master. Scrum is an Agile framework for getting work done. It describes an iterative way of releasing work, using small increments of shippable products. In other words, you drip out usable functionality instead of waiting for a ‘big bang’ launch at the end of the project.

Even if you are not part of the Scrum team, you may have to work alongside people working in this way and it helps to have a little background about what their roles consist of.

First, a Scrum Master is a specific role on a Scrum team, which is not the role of the project manager. They are not the owner of the product either (and we’ll come on to Product Owners next). A Scrum Master helps the team use the Scrum tools and approaches effectively. They are supporting the team to use the processes in the best possible way to get the best possible outcomes.

A Scrum Master understands the values and techniques behind Scrum. They are subject matter experts in this domain and can support others in using the practices required. They support the Product Owner on the team too, by making sure that there is a list of requirements for them to prioritise, which is known in Scrum terms as the product backlog.

While the Scrum Master is primarily a coach and mentor to the team, they also have an organisational role to play on the team. They maintain the release plan and organise meetings. They facilitate conversations and keep the teams talking. They remove roadblocks and act in a way that maintains efficiency. The person in this role is constantly looking for ways to help the team learn what works so they can do more of that. It’s a role that is responsible for the processes but not the people.

Product Owner

Product Owners are another core part of a Scrum team that you might come across on software development projects or through your work on other projects. It’s not a project management role but it is complementary.

The Product Owner is a bit like the ‘traditional’ project sponsor. The person in this role is responsible for the project requirements and making sure that these are prioritised in a way that makes sense for the business. The requirements sit in what is known as a product backlog, and the Product Owner is responsible for setting and communicating the priorities related to these. The Product Owner has the business needs at heart and uses their business knowledge to ensure the project delivers something of value and strategic fit to the organisation.

The Product Owner is the main decision maker on an Agile project, and as Agile is a fast-moving environment, they could be called upon to make decisions frequently and in a timely fashion so that the project doesn’t get held up. Project sponsors are often less hands-on than a Product Owner.

![]()

Project managers need a mix of skills. Below Aaron Porter, PMP and Certified Scrum Master, explains which he feels are the most relevant to IT project managers today.

For IT project managers working in a traditional environment the top two skills are: hard skill – effective scheduling and the ability to manage schedule dependencies between projects; and soft skill – the ability to tailor your communications to your audience; communicating both up and down the leadership pipeline.

For Agile project managers, the top skill is being able to manage effective retrospectives. This is probably less critical for an experienced Agile team, but ongoing improvement of team processes is critical. This allows you to evaluate what does and doesn’t work, and to create and execute a plan to improve team processes.

Aaron Porter, USA, beauty and wellness industry

As a project manager you’ll also end up speaking to users. ‘Users’ is an unfriendly term for the people who are on the receiving end of whatever it is you are delivering as part of your project. If it’s a new accounts payable system, it’s the accounts payable clerks who deal with invoicing and client accounts. If it’s barcoding technology for your warehouse, it’s the pickers who use the handheld devices to scan boxes of products.

You may have a user representative on the project team – one of your subject matter experts. However, your project touches a group of users, not just that one individual, and they may come from a number of different teams or perhaps even be members of the public. As a project manager you’ll come across the other users through your communication efforts, workshops, presentations, training and user acceptance testing (which will probably involve a number of individuals, not just the person who sits on the core project team as the user rep).

Users may make up your largest stakeholder group.

Business change manager

In some large organisations, change management is a specific discipline and you may find yourself working alongside a business change manager. The role of the business change manager is to integrate and embed into the organisation the change delivered by a project. This is very different from handling project change requests – for example, the request to add new features, which are handled within the project team using change control.

Business change managers (also known as business relationship managers) support and deliver change management in a business context. We can define this as the way we facilitate the shift from current practice to new practice in order to achieve a benefit.9

The change management role could be fulfilled by a team leader or functional expert. You might not have someone on the project team with that job title, but you should have someone focused on doing the work. In the absence of someone within the team doing change management, you can take on this role. Change management requires you to think about how the IT project is going to impact end users and what would help them get ready for whatever is about to be different. Change management tools include training, coaching, communication, readiness assessments and more.

Change management is implicit in the role of a project manager because it supports project success. The readier the people receiving the change, the more likely it is that it will stick and that the organisation will achieve the benefit it seeks.

External suppliers

Commonly, the external suppliers you use on a project are going to be third party vendors brought on to the project to manage an area of delivery where your own in-house team are not expert. This is often the case for packaged software deployment, where you buy a new system and the vendor’s own team implements it in your business. Larger solutions, such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) products, have partner relationships with implementation firms. You don’t get Oracle or SAP employees deploying their IT systems within your business, for example, but you would get certified partners who meet certain criteria and are experienced with the tools and what it takes to get them operational in a company.

Projects like this could involve a longer-term relationship with the supplier as they could be offering technical support and maintenance through an ongoing support contract, or you could include knowledge transfer tasks in the project plan so that your own team can manage the ongoing responsibilities of maintaining the software.

In these cases, the vendor will appoint an account manager or project manager to be your single point of contact into their resources. This is the person you’ll meet with regularly to get an update on progress for their portions of the work and to discuss any risks, issues and anything else.

You may also have contract resources brought in on an individual basis, perhaps because you need an expert with this particular type of systems background for the duration of the project. Contractors are useful when you don’t need that level of expertise in the business longer term, or when you just need an experienced extra pair of hands.

Some of your external suppliers could be companies with subject matter expertise, such as a legal counsel with particular depth of knowledge in an area of technical contract law, required before you embark on a new venture.

The role of the supplier on the project will differ depending on what you are hiring them to do. Their responsibilities will range from deploying technical solutions across your entire estate to advising on an element of accessible web design on a two-day engagement. They are providing a particular service or product required for the project’s ultimate success.

Projects (even relatively small and simple ones) often have multiple suppliers. Managing multiple, overlapping vendors is part of your role as a project manager. Your objective will be to help them work together as a single team. While there are some commercially confidential details that you won’t be able to share with them, it’s easiest and most effective to think of the supplier project manager as an integral part of your project team and not someone ‘on the outside’.

Regulatory bodies/government agencies

Another external stakeholder group to be aware of is regulatory bodies. These are groups that regulate your industry and practice. They set standards and policies, and enforce them, often with the weight of the law.

While not every project is going to have a regulatory or compliance element, there are plenty that will. For example, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) includes provision for reporting breaches to the relevant lead supervisory authority, so you could expect a project that was dealing with large quantities of personal data to want to be aware of what body that was and what, if any, additional requirements the regulations placed on the company.

Be aware of the regulatory bodies and government agencies that have a direct impact on your business and market, so you can ensure your project is compliant where it needs to be. There’s an overlap here with your IT security or information governance teams.

If you are working in public sector projects, the role of government agencies becomes even more acute. Oversight for large UK public sector projects is carried out by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, which is the government’s centre of expertise for infrastructure and major projects.

Other roles

As each project is unique it’s impossible to define the exact roles that your project will need. The explanations of the roles already discussed in this chapter are a good starting point for the major interfaces and relationships, but you’ll quickly find that your project has implications for a wide range of other departments and roles.

Here are some other areas that your project might touch. These groups may be considered internal suppliers if they provide you with goods or services required for the project, or they may be subject matter experts for you to consult:

Health and safety: You may have to get input from health and safety managers within the business, depending on what your project is going to deliver.

Accounting and finance: Your project might need a dedicated capital expenditure, projects or overheads analyst if there are significant amounts of money being spent. If you have the opportunity to draw on expertise from the finance team for your project budget management, then do. It’s one less thing you’ll have to worry about and they are uniquely placed to help.

Legal: The role that expert counsel might play has already been mentioned briefly, but your own in-house legal team and data protection experts may also need to get involved.

Security: Many IT projects have huge data security implications, so you may find that you need to involve the information governance and security teams prior to designing your solution. They may also coordinate penetration testing (or other forms of ‘ethical hacking’) prior to signing off your solution as appropriate to move forward into delivery.

Sustainability and ethical practice: If your business has sustainability targets or ethical policies, you may find that your project needs to involve the guardians of these processes prior to design or delivery.

HR: Projects of all sizes affect the people in the organisation. Talk to your HR team early to understand any involvement they should have. They will be particularly helpful if your project involves hiring new people or making anyone redundant, and they can also advise you of any relevant unions which would need to be consulted prior to making any changes.

IT projects sometimes create additional businesses, or take over a service provided by another business, and in cases like these you would want to be aware of the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) regulations (TUPE). Your HR team can advise if this applies, or if there are other aspects of employment law that you should be building into your project.

You might have any of these people on your core project team if you are expecting them to be heavily involved, but it’s more likely that they will pop in and out of the project team as and when you require their input.

TOOLS FOR UNDERSTANDING YOUR PROJECT TEAM AND INTERFACES

There are a number of tools project managers use to keep on top of the seemingly never-ending set of working relationships on a project.

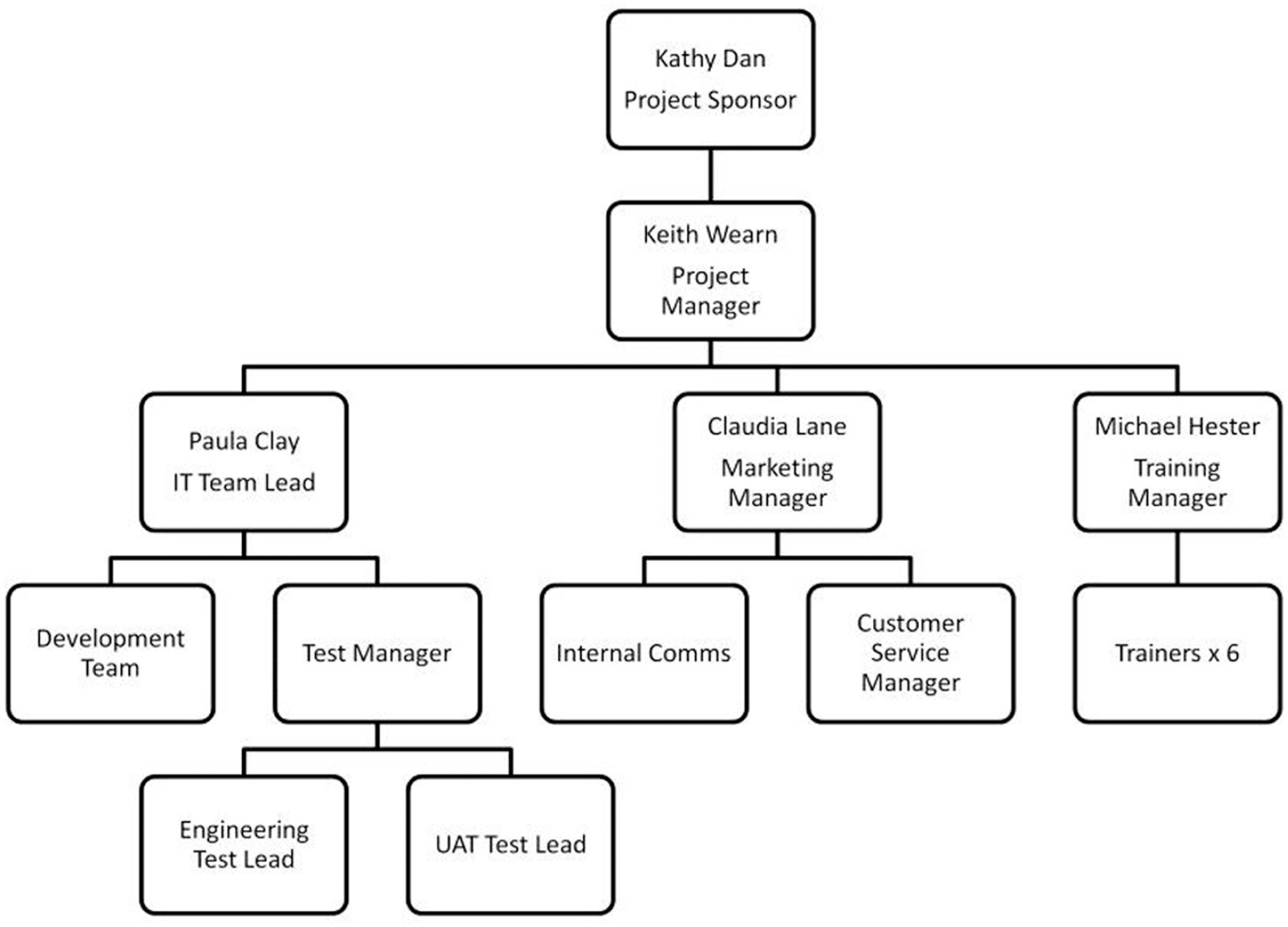

Project organisation charts

The most straightforward interfaces between a project manager and other roles in the business are codified in the project organisation chart. An example project organisation chart is given in Figure 3.3 showing a simple team structure.

There’s a slightly more complicated project team structure in Figure 3.4, which has more people involved in a variety of roles. The interfaces between you and others in the organisation may look like this, or may look different depending on the project and your company structure.

Spend some time working out how best to display your project structure if it’s complex. Your organisation chart might need to include external people (identified as such in some way). There might also be overlap between the roles. One individual can hold a number of roles, so if you’ve designed the chart in a role-based way you might have names on the chart more than once.

If you have space, your organisation chart can serve as a team directory if you include the contact details of each person.

Stakeholder register

The stakeholder register is a detailed list of the different individuals and groups who should be involved and engaged in the project. This is particularly important for IT projects. Often it’s quite easy to think of the other technical teams who are affected by this change and it’s possible to overlook the impact the work could have on other departments. The stakeholder register forces you to think through who else needs to know about your work.

The stakeholder register includes names and contact information. More useful than that are two columns that you shouldn’t overlook:

Expectations: This is where you can note down what each stakeholder is expecting from the project. What does success look like for them? Having this on your stakeholder register will prompt you to ask them the question. Then summarise the answer and record it on the template so you don’t forget.

Influence: Categorise your stakeholders as ‘supporter’, ‘neutral’ or ‘opposed’ (or use other similar terms of your choice).

These two columns will provide useful information that will help shape how you interact with the individuals, teams and groups on the project. You can look for mismatched expectations that could lead to conflict. Knowing how influential your stakeholders are, and how they feel about the project (and note that this can change over time) will help you prioritise your time on engagement activities. You may want to spend more time with those who are not feeling positive so that you can convince them that the project is worth their time.

There is a lot of personal information included in a detailed stakeholder register, and that’s fine if everything you write down about your stakeholders is positive. The moment you start labelling someone in the influence column as ‘project denouncer; highly negative’ or something like that, then you need to be really careful about who has sight of this document.

Use your professional judgement and if in doubt don’t share it.

RACI matrix

A RACI matrix (pronounced ‘racy’) is a way of categorising stakeholders to define their roles and responsibilities on a project. Names (or roles, but names are better) go across the top. Tasks or project stages go down the side, as you can see in Table 3.1. Then you plot which person is involved in which activity.

The RACI acronym stands for:

- Responsible: These people have responsibility for certain tasks. They are the ‘creator’ of the deliverable.

- Accountable: This is the person accountable for the job in hand who will give approval.

- Consulted: These people would like to know about the task and you would seek their opinions before a decision or action.

- Informed: This group gets one-way communication to keep them up-to-date with progress and other messages after a decision or action.

Put the right letter in the relevant box to show how that person is going to get involved with the project and note that individuals can fall into several categories.

You might also hear these charts referred to as a RASCI matrix (pronounced ‘rasky’). These include an extra option to mark people as ‘Supportive’ (that’s the ‘S’). This is someone who can provide resources, information or will generally support you in getting the work done. Either is fine to use, and what you use may depend on your company standards.

Predominantly, RACI and RASCI are used as a roles and responsibilities matrix. They clarify the relationships between tasks and people on projects. It’s a rookie mistake to assume that people always know what they are supposed to do. A chart that sets it out clearly like this explains what you are expecting of each person on the project.

Once you’ve created your chart10 you can include it in your roles and responsibilities documentation for the project.

A RACI or RASCI chart is also useful for communications planning because it can give you ideas about which stakeholders need which type of communication at what points. It can flag which decisions are going to be made by consensus – this is definitely helpful to identify early on, because consensus decision making can be tough.

Another use for it is for process mapping. If you are going to change a process as part of your project you can use RACI to step through the process and record who is going to be affected by any process change. It’s a really useful tool.

However, your chart isn’t much help unless you keep it up to date as people do change roles and move into different positions of responsibility during a project, so when you are managing a project, make time to review it periodically.

Roles and responsibilities document

The roles and responsibilities document is very helpful, and should be put together in the early stages of the project. It’s a formal way of setting out what each role is responsible for on a project team. As a minimum, this document includes the role title and a list of what that role needs to do on the project. It’s also helpful, but not required, to include the names of people holding the roles. This can help the individuals focus on their particular responsibilities so that they can really own them.

You can add other information into the roles and responsibilities document including:

- authority and sign off levels per role;

- budget associated with that role;

- staff members reporting to that role;

- qualifications required to do the role;

- core skills and competencies required to do the role.

The organisation chart, the stakeholder register, the RACI matrix and the roles and responsibilities document combine to give you a detailed picture of the people who are required to make your project successful. You can find out where to get copies of templates for these documents in Appendix 3.

![]()

Mayte Mata-Sivera ‘found’ IT project management after studying chemical engineering. She describes how she built her skills in a new area below.

A lot of people ask me how I developed my career in IT after six hard years at Chemical Engineering School in Valencia, Spain. I’m one of those examples of coincidences in your life that help you to discover a career path that you really love.

A week before my graduation, one of the big 5 firms in the IT world reached out to me, offered me an internship plus free tuition for an SAP course. I struggled for days about accepting the offer, but I did take it in the end. I was not very tech savvy, but thanks to my mentors and coach in the company I learnt not only IT but also leadership skills that I continue to use and develop today.

After my experience in several IT organisations, I’ve realised that my passion is being a great project manager. There are some myths about project management. It’s not just spending the day in front of the computer sending emails with due dates! It is also engagement, communication, leadership… I want to be one of those who really inspire the team, one of those who create more leaders.

For developing some of my skills as project manager, I used not only my personal and professional network, but also social media platforms like LinkedIn and projectmanagement.com. They gave me the availability to choose the project that I wanted to lead, the group of people that I love to work with and to create a team. Also, using social media, I developed mentorship and coaching relationships with people around the world that helped me learn something new every day.

Mayte Mata-Sivera, USA, IT

SUMMARY

In this chapter we looked at the role of the project manager within an IT organisation.

As this chapter explains, project managers work in a range of team structures. They work with a huge range of individuals: every team requires subject matter experts and support from different areas of the business and the project manager needs to be able to build working relationships with them all.

Read this

Emotional Intelligence for Project Managers (2nd Edition) by Anthony Mersino: A deep dive into the behaviours of successful project managers and how you can manage your own behaviour to drive better results in others.

Practical People Engagement by Patrick Mayfield: A book about leading change through the power of relationships. Excellent for people working in a matrix structure where you need successful working relationships in order to get anything done.

Do this

Find the organisation chart for a project or team you work on (or if you aren’t working, find a sample chart online). Read through the different roles and check you understand what each does on the team.

Share this

Plan. Monitor. Control. Repeat #itpm

Stakeholder engagement: more effective than trying to manage stakeholders #itpm