Chapter 13

Starting Your Project Team Off on the Right Foot

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Confirming team member assignments and filling in any gaps

Confirming team member assignments and filling in any gaps

![]() Developing your team’s identity along with its operating procedures

Developing your team’s identity along with its operating procedures

![]() Creating systems and schedules for project control

Creating systems and schedules for project control

![]() Introducing your project with an official announcement

Introducing your project with an official announcement

![]() Laying the groundwork for the post-project review

Laying the groundwork for the post-project review

After intense work on a tight schedule, you submit your project plan (the single document that integrates and consolidates your project’s scope statement, stakeholder register, work breakdown structure, responsibility assignment matrix, schedule, resource requirements, budget, and all subsidiary plans for providing project support services) for review and approval. A few days later, your manager comes to you and says,

- “I have some good news and some bad news. Which would you like to hear first?”

- “Tell me the good news,” you respond.

- “Your plan’s been approved.”

- “So, what’s the bad news?” you ask.

- “Now you have to do the project!”

Starting off your project correctly is a key to ultimate success. Your project plan describes what you’ll produce, the work you’ll do, how you’ll do it, when you’ll do it, and which resources you’ll need to do it. When you write your project plan, you base it on the information you have at the time, and, if information isn’t available, you make assumptions. The more time between your plan’s completion and its approval, the more changes you’re likely to find in your plan’s assumptions as you actually start your project.

As you prepare to start your project, reconfirm or update the information in your plan, determine or reaffirm which people will play roles in your project and exactly what those roles will be, and prepare the systems and procedures that will support your project’s performance. This chapter tells you how to accomplish these tasks and get your project off to a strong start.

Finalizing Your Project’s Participants

A project stakeholder is a person or group that supports, is affected by, or is interested in your project (see Chapter 4 for details on how to identify project stakeholders). In your project plan, you describe the roles you expect people to play and the amount of effort you expect team members to invest. You identify the people by name, by title or position, or by the skills and knowledge they need.

This section shows you how to reaffirm who will be involved in your project. It also helps you make sure everyone’s still on board — and tells you what to do if some people aren’t.

Are you in? Confirming your team members’ participation

To confirm the identities of the people who’ll work to support your project, you have to verify that specific people are still able to uphold their promised commitments and, if necessary, recruit new people to fulfill any remaining gaps.

Inform them that your project has been approved and when the work will start.

Not all project plans get approved. You rarely know in advance how long the approval process will take or how soon your project can start. Inform team members as soon as possible so they can schedule the necessary time.

Confirm that they’re still able to support your project.

People’s workloads and other commitments may change between the time you prepare your plan and your project’s approval. If a person is no longer able to provide the promised support, recruit a replacement as soon as possible (see the later section “Filling in the blanks” for guidelines).

Explain what you’ll do to develop the project team and start the project work.

Provide a list of all team members and others who will support the project. Also mention the steps you’ll take to introduce members and kick off the project.

Reconfirm the work you expect them to perform, the schedules and deadlines you expect them to keep, and the amount of time you expect them to spend on the work.

Clarify specific activities and the nature of the work to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Depending on the size and formality of your project, you can use any format from a quick email to a formal work-order agreement to share this information with the people who will be involved in your project.

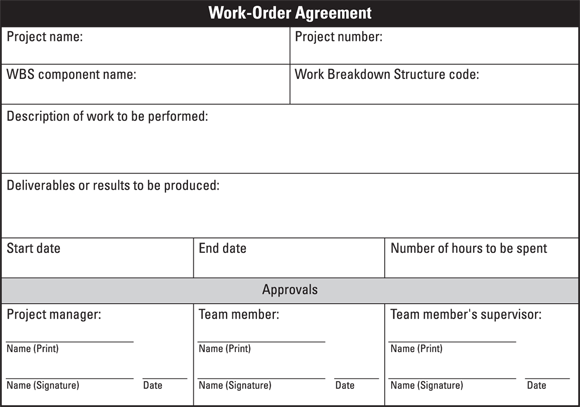

As Figure 13-1 illustrates, a typical work-order agreement includes the following information:

- Identifiers: The identifiers include the project name, project number, and work breakdown structure (WBS) code and component name (for more on WBS, see Chapter 6). The project name and number confirm that your project is now official. You use the WBS code and component name to record work progress as well as time and resource charges.

- Work to be performed and deliverables or results to be produced: These details describe the different activities and procedures involved in the project, as well as outputs of the project.

- Activity start date, end date, and number of hours to be spent: Including this information reaffirms:

- The importance of doing the work within the schedule and budget

- Acknowledgment from the person who’ll do the work that they expect to do the described work within these time and resource constraints

- The criteria you’ll use to assess the person’s performance

- Written approvals from the person who’ll do the work, their supervisor, and the project manager: Including these written approvals increases the likelihood that everyone involved has read and understood the project’s elements and is committed to support it.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 13-1: A typical work-order agreement.

Assuring that others are on board

Other people may also play a role in your project’s success, even though they may not officially be members of your project team. Two such groups are drivers (people who have a say in defining the results of your project) and supporters (people who will perform a service or provide resources for your team).

Two other special stakeholders are your project champion and your project executive sponsor. Both are people in high positions in the organization who strongly support your project; who will advocate for your project in disputes, planning meetings, and review sessions; and who will take necessary actions to help ensure your project’s success (see Chapter 4 for more on these different types of project stakeholders).

Contact your project champion and all other drivers and supporters to:

- Inform them that your project has been approved and when work will start.

- Reaffirm your project’s objectives.

- Confirm with identified drivers that the project’s planned results still address their needs.

- Clarify with supporters exactly how you want them to help your project.

- Develop specific plans for involving each stakeholder throughout the project and keeping them informed of progress.

Filling in the blanks

If your plan identifies proposed project team members only by job title, position description, or skills and knowledge (and not by specific names), you have to find actual people to fill the specified roles. You can fill the empty roles by assigning responsibility to someone already on your organization’s staff, by recruiting a person from outside your organization, or by contracting with an external organization. If you don’t have the authority to hire a person yourself, work with the functional manager to whom the new hire will report.

Whichever method you choose, prepare a written description of the activities you want each person to perform. This description can range from a bulleted list in email for informal projects to a written job description for more formal ones.

- Project name, number, start date, and projected end date

- Necessary skills and knowledge

- Supervision to be provided

- Activities to be performed and start and end dates

- Anticipated level of effort

If you plan to look inside your organization to recruit team members for roles not yet filled, do the following:

- Identify potential candidates by working with functional area managers and your human resources (HR) department.

- Meet with the candidates to discuss your project, describe the work involved, and assess their qualifications.

- Choose the best candidates and ask them to join your team.

- Document the agreements you make with the new team members.

Also, if you plan to obtain the support of external consultants, work with your organization’s contracts office. Provide the contracts office with the same information that you provide your HR office. Review the contract document before your contracting officer signs it.

In addition to filling your empty team member roles, work with people in key organizational units to identify people, other than team members, who will support your project (for example, a contracts specialist or a procurement specialist, as long as they aren’t officially on your project team). After you identify these people, do the following:

- Meet with them to clarify your project’s goals and anticipated outputs and the ways in which they will support your performance.

- Develop plans for involving them and keeping them informed of progress throughout your project.

For example, let’s say your organization, a contract e-commerce website development firm, is structured by business units aligned to specific markets within the retail industry, such as apparel, home goods and furniture, sporting goods, electronics, and so on. You are tasked with initiating a project within your business unit to develop an e-commerce website for a well-known online apparel retailer. However, you have recently learned that all of your business unit’s Java developers are assigned to other long-term apparel projects for the next six months. Your client expects their website to be live in six months! In speaking with your colleagues in other business units, you learn that they are not experiencing the same resource drought and, in fact, are even considering the need to downsize their existing staff. Does it really matter, in this particular example, if the Java developers assigned to your team routinely work on apparel projects or would competent (and available) developers from the electronics or sporting goods business units have the same skills and ability to translate your project’s requirements into technically-sound Java software code? With an open mind and some creative thinking, you may be able to turn this scenario into a win-win for everyone!

Developing Your Team

Merely assigning people to tasks doesn’t create a project team. A team is a collection of people who are committed to common goals and who depend on one another to do their jobs. Project teams consist of members who can and must make a valuable and unique contribution to the project.

A team is different from other associations of people who work together. For example

- A group consists of people who work individually to accomplish their particular assignments on a common task.

- A committee consists of people who come together to review and critique issues, propose recommendations for action, and, on occasion, implement those recommendations.

- Goals: What the team as a whole and members individually hope to accomplish

- Roles: Each member’s areas of specialty, position on the team, assignments, authority, responsibilities, and accountability

- Processes: The techniques that team members will use to perform their project tasks

- Relationships: The attitudes and behaviors of team members toward one another

This section discusses how to begin creating your team’s identity by having members review and discuss the project plan, examine overall team and individual team member goals, agree on everyone’s roles, and start to establish productive working relationships.

Reviewing the approved project plan

Team members who contributed to the proposal can remind themselves of the project’s background and purpose, their planned roles, and the work to be done. They can also identify situations and circumstances that may have changed since the proposal was prepared and then review and reassess project risks and risk management plans.

New team members can understand the project’s background and purpose, find out about their roles and assignments, raise concerns about timeframes and budgets, and identify issues that may affect the project’s success.

Developing team and individual goals

Team members commit to your project when they believe their participation can help them achieve worthwhile professional and personal goals. Help team members develop and buy into a shared sense of the project goals by doing the following:

- Discuss the reasons for the project, its supporters, and the impact of its results (see Chapter 5 for a discussion of how to identify the needs your project will address).

- Clarify how the results may benefit your organization’s clients.

- Emphasize how the results may support your organization’s growth and viability.

- Explore how the results may impact each team member’s job.

Specifying team member roles

Nothing causes disillusionment and frustration faster than bringing motivated people together and then giving them no guidance on how to work with one another. Two or more people may start doing the same activity independently, and other activities may be overlooked entirely. Eventually, these people gravitate toward tasks that don’t require coordination, or they gradually withdraw from the project to work on more rewarding assignments.

To prevent this frustration from becoming a part of your project, work with team members to define the activities that each member works on, the nature of their roles, and the impact of their contributions to the team as a whole. Possible team member roles include the following:

- Primary responsibility: Has the overall obligation to ensure the completion of an activity.

- Secondary or supporting responsibility: Has the obligation to complete part of an activity.

- Approval: Must approve the results of an activity before work can proceed.

- Consultation resource: Can provide expert guidance and support if needed.

- Required recipient of project results: Receives either a physical product from an activity or a report of an activity.

Defining your team’s operating processes

Develop the procedures that you and your team will use to support your day-to-day work. Having these procedures in place allows people to perform their tasks effectively and efficiently; it also contributes to a positive team atmosphere. At a minimum, develop procedures for the following:

- Communication: These processes involve sharing project-related information in writing and through personal interactions. Communication procedures may include:

- When and how to use email to share project information

- Which types of information should be in writing

- When and how to document informal discussions

- Who is responsible for key communications (i.e., status reports, project plan and budget updates, etc.)

- How to set up regularly scheduled reports and meetings to record and review progress

- How to address special issues that arise

- Decision-making: These processes involve deciding among alternative approaches and actions. Develop guidelines for making the most appropriate choice for a situation, including consensus, majority rule, unanimous agreement, and decision by technical expert. Also develop escalation procedures — the steps you take when the normal decision-making approaches get bogged down.

- Conflict resolution: These processes involve resolving differences of opinion between team members (see the later section “Resolving conflicts” for details on two conflict resolution procedures).

Supporting the development of team member relationships

On high-performance project teams, members trust each other and have cordial, coordinated working relationships. But developing trust and effective work practices takes time and concerted effort.

- Work through conflicts together (see the next section for more on conflict resolution).

- Brainstorm challenging technical and administrative issues.

- Spend informal personal time together, such as having lunch or participating in non-work-related activities after hours.

Resolving conflicts

With most projects, the question isn’t if disagreements will occur between team members; it’s when. So you need to be prepared to resolve those differences of opinion with a conflict resolution plan that includes one or both of the following:

- Standard approaches: Normal steps that you take to encourage people to develop a mutually agreeable solution

- Escalation procedures: Steps you take if the people involved can’t readily and reasonably resolve their differences in a timely manner

Minimizing conflict on your team

Throughout the life of a project, conflicts may arise around a myriad of professional, interpersonal, technical, and administrative issues. The first step toward minimizing the negative consequences of such conflicts is to avoid them before they occur. The following tips can help you do just that:

- Encourage people to participate in the development of the project plan.

- Get commitments and expectations in writing.

- Frequently monitor work in progress to identify and resolve any conflicts that arise before they become serious.

If a conflict does arise, one or more of the participants in the conflict or one or more people with knowledge of the issues around which the conflict arose need to take an active role to resolve the conflict. The person or people chosen for this task should have knowledge of the conflict and the issues surrounding it, the techniques of proactive conflict resolution, the respect of the people involved in the conflict, and no preconceived preferences or biases for any of the solutions of the people involved in the conflict. Whether they informally assume the responsibility to help resolve the conflict or are assigned by the project manager or another member of management to do so, they should do the following:

- Assess the conflict and gather all related background information to identify the likely and underlying root cause(s) for it.

- Select and follow an appropriate resolution strategy.

- Maintain an atmosphere of mutual respect and cooperation when trying to find an acceptable solution.

As you work to understand the reasons for a conflict, note that conflicts can arise over one or more of the following:

- Facts: Objective data that describe a situation

- Methods: How a person responds to particular values of data

- Goals: What someone is ultimately trying to accomplish when they resolve the conflict

- Values: The basic personal feelings and principals that motivate someone’s behavior

Keep in mind that personal beliefs about each of these four types of information can be due to:

- Incorrect, lack of, or different information

- Different perceptions or inferences based on the same information

- Different reactions to the same information based on the position a person occupies, the role they play on the team, or their background and prior exposure to similar information

Acting out conflict resolution with a simple example

Suppose that Perla and Jimmy have been assigned to develop recommendations for how to improve the production of a poorly performing unit in their company. After reviewing some related reports and having a few discussions, Perla has decided the best way to improve performance is to fire two of the four people in the unit and retrain the other two. In contrast, Jimmy has decided the only way to improve the unit’s performance is to fire all four people.

At the moment, Perla and Jimmy are at a standoff, but if they’re willing, they can take one of the following approaches to resolve their conflict:

- Competition (forcing): Both people assertively act to have their solution to the conflict chosen (there’s one winner and one loser).

- Accommodation (smoothing): One person chooses to acquiesce and give into the other person’s solution (there’s one winner and one loser).

- Avoidance (withdrawing): One person chooses not to acknowledge the conflict at all. For example, Perla may draft a memo that two people in the unit can be trained and the other two fired, entirely and conveniently ignoring the fact that Jimmy wants all four people to be fired (there’s one winner and one loser).

- Compromise (giving a little, getting a little): Both people give in a little to the other person’s proposed solution (each person wins and loses in some way).

- Collaboration (problem-solving): Both people get what they want (there are two winners and no losers).

As you consider these possible resolutions, keep in mind the following two points:

- Conflict is natural and not necessarily “bad.” Conflict that focuses on the merits of alternative solutions and maintains respect for the parties involved can result in a solution that’s better than the original choice of either of the participants. Conflict, for the right reasons and when addressed appropriately, is healthy and should be encouraged within reason.

- Most people understand that they may have to “lose” a conflict every once in a while, and they learn to absorb the blow to their psyche. However, if they lose a disproportionate number of the conflicts in which they choose to participate, they may decide to withdraw from the team and not share their true feelings.

- Suggest that participants develop sets of criteria for rating solutions instead of just arguing strongly for one solution.

- Encourage participants to develop additional possible solutions instead of just arguing that their original solution alone should be selected.

- Allow sufficient time to explore the different alternatives proposed.

- Remain objective and don’t take sides during the discussions. If one person senses that you’re predisposed to the other person’s solution, they’ll think the decision process was unfair and not accept any solution but their own.

All together now: Helping your team become a smooth-functioning unit

When team members trust each other, have confidence in each other’s abilities, can count on each other’s promises, and communicate openly, they can devote all their efforts to performing their project work instead of spending their time dealing with interpersonal frustrations.

Help your team achieve this high-performance level of functioning by guiding it through the following stages:

- Forming: This stage involves identifying and meeting team members and politely discussing project objectives, work assignments, and so forth. During this stage, you share the project plan, introduce people to each other, and discuss each person’s background, organizational responsibilities, and areas of expertise.

Storming: This stage involves raising and resolving personal conflicts about the project or other team members. As part of the storming stage, do the following:

- Encourage people to discuss any concerns they have about the project plan’s feasibility and make sure you address those concerns.

- Encourage people to discuss any reservations they may have about other team members or team members’ abilities.

- Focus these discussions on ways to ensure successful task and project performance; you don’t want the talks to turn into unproductive personal attacks.

Initially, you can speak privately with people about issues you’re uncomfortable bringing up in front of the entire team. Eventually, though, you must discuss their concerns with the entire team to achieve a sense of mutual honesty and trust.

Initially, you can speak privately with people about issues you’re uncomfortable bringing up in front of the entire team. Eventually, though, you must discuss their concerns with the entire team to achieve a sense of mutual honesty and trust.Norming: This stage involves developing the standards and operating guidelines that govern team member behavior. Encourage members to establish these team norms instead of relying on the procedures and practices they use in their functional areas. Examples of these norms include:

- How people present and discuss different points of view: Some people present points of view politely, while others aggressively debate their opponents in an attempt to prove their points and, sometimes more accurately, disprove others’ points.

- Timeliness of meeting attendance: Some people always show up for meetings on time, while others are habitually 15 minutes late.

- Participation in meetings: Some people sit back and observe, while others actively participate and share their ideas.

At a team meeting, encourage people to discuss how team members should behave in different situations. Address the concerns people express and encourage the group to adopt team norms. Establish ground rules for what is and is not appropriate conduct during meetings, including whether or not it is acceptable for meeting attendees to read and send emails or if side conversations are allowed while someone is addressing the entire room.

At a team meeting, encourage people to discuss how team members should behave in different situations. Address the concerns people express and encourage the group to adopt team norms. Establish ground rules for what is and is not appropriate conduct during meetings, including whether or not it is acceptable for meeting attendees to read and send emails or if side conversations are allowed while someone is addressing the entire room.- Performing: This stage involves doing project work, monitoring schedules and budgets, making necessary changes, and keeping people informed.

- Adjourning: This stage involves the completion of project work, formal closure of the project, and the official release of resources to focus on other projects and tasks.

- Your team won’t automatically pass through these stages; you’ll have to guide them. Left on their own, teams often fail to move beyond the forming stage. Many people don’t like to confront thorny interpersonal issues, so they simply ignore them. Your job is to make sure your team members address what needs to be addressed and become a smooth-functioning team.

- Your involvement as project manager in your team’s development needs to be heavier in the early stages and lighter in the later ones. During the forming stage, you need to take the lead as new people join the team. Then, in the storming stage, you take a strong facilitative role as you guide and encourage people to share their feelings and concerns. Although you can help guide the team as it develops its standards and norms during the norming stage, your main emphasis is to ensure that everyone participates in the process. Finally, if you’ve navigated the first three stages successfully, you can step back in the performing stage and offer your support as the team demonstrates its ability to function as a high-performing unit. Your involvement will increase again in the adjourning stage, as many typical project-closure tasks are your responsibility.

- On occasion, you may have to revisit a stage you thought the team had completed. For example, a new person may join the team, or a major aspect of the project plan may change.

- If everything goes smoothly on your project, it doesn’t matter whether the team has successfully gone through the forming, storming, and norming stages. But when the project runs into problems, your team may become dysfunctional if it hasn’t progressed successfully through each stage. Suppose, for example, that the team misses a major project deadline. If team members haven’t developed mutual trust for one another, they’re more likely to spend time searching for someone to blame than working together to fix the situation.

- As the project manager, you need to periodically assess how the team feels it’s performing; you then have to decide which, if any, issues the team needs to work through. Managing your team is a project in and of itself!

Laying the Groundwork for Controlling Your Project

Controlling your project throughout its performance requires that you collect appropriate information, evaluate your performance compared with your plan, and share your findings with your project’s stakeholders. This section highlights the steps you take to prepare to collect, analyze, and share this information (see Chapter 14 for full details on maintaining control of your project).

Selecting and preparing your tracking systems

Effective project control requires that you have accurate and timely information to help you identify problems promptly and take appropriate corrective action. This section highlights the information you need and explains how to get it.

Throughout your project, you need to track the following key performance indicators, or KPIs:

- Schedule achievement: The assessment of how well you’re meeting established dates.

- Personnel resource use: The levels of effort people are spending on their assignments.

- Financial expenditures: The funds you’re spending for project resources.

See Chapter 14 for a detailed discussion of the information systems you can use to track your project’s progress.

If you use existing, enterprise-wide information systems to track your project’s schedule performance and resource use, set up your project on these systems as follows (see Chapter 14 for information on how to decide whether to use existing information systems to support your project’s monitoring and control):

- Obtain your official project number. Your project number is the official company identifier for your project. All products, activities, and resources related to your project are assigned that number. Check with your organization’s finance department or project management office to find out your project’s number and check with your finance or information technology (IT) department to determine the steps you must take to set up your project in the organization’s financial tracking system, labor recording system, and/or activity tracking system.

- Finalize your project’s work breakdown structure (WBS). Have team members review your project’s WBS and make any necessary changes or additions. Assign identifier codes to all WBS elements (refer to Chapter 6 for a complete explanation of the WBS).

Set up charge codes for your project in the organization’s labor tracking system. If team members record their labor hours by projects, set up charge codes for all WBS activities. Doing so allows you to monitor the progress of individual WBS elements, as well as the total project.

If your organization’s system can limit the number of hours for each activity, enter those limits (see the later section “Setting your project’s baseline” as well as Chapter 14 for how to establish targets for your project’s schedule, resource needs, and budget). Doing so ensures that people don’t inadvertently charge more hours to activities than your plan allows.

If your organization’s system can limit the number of hours for each activity, enter those limits (see the later section “Setting your project’s baseline” as well as Chapter 14 for how to establish targets for your project’s schedule, resource needs, and budget). Doing so ensures that people don’t inadvertently charge more hours to activities than your plan allows.- Set up charge codes for your project on your organization’s financial system. If your organization tracks expenditures by project, set up the codes for all WBS activities that have expenditures. If the system can limit expenditures for each activity, enter those limits.

Establishing schedules for reports and meetings

To be sure you satisfy your information needs and those of your project’s stakeholders, set up a recurring schedule of status reports you’ll prepare and meetings you’ll hold during the project. Planning your communications with your stakeholders in advance helps ensure that you adequately meet their individual needs and allows them to reserve time on their calendars to attend the meetings.

Meet with project stakeholders and team members to develop a schedule for regular project meetings and progress reports. Confirm the following details:

- What reports will be issued

- Which meetings will be held and what their specific purposes will be

- When reports will be issued and when meetings will be held

- Who will receive the reports and attend the meetings, including who is considered mandatory and optional

- Which formats the reports and meetings will be in and what they’ll cover

See Chapter 15 for a discussion of the reports and meetings you can use to support ongoing project communications.

Setting your project’s baseline

The project baseline is the version of your project’s plan that guides your project activities and provides the comparative basis for your performance assessments. At the beginning of your project, use the plan that was approved at the end of the organizing-and-preparing stage, modified by any approved changes made during the carrying-out-the-work stage, as your baseline (see Chapter 1 for a discussion of the project life cycle stages). During the project, use the most recent approved version of the project plan as your baseline (see Chapter 14 for more discussion on setting, updating, and using your project’s baseline to control your project).

Hear Ye, Hear Ye! Announcing Your Project

After you’ve notified your key project stakeholders (that is, the drivers and supporters) that your project has been approved and when it’ll start, you have to introduce it to others who may be interested (known as observers; see Chapter 4 for a discussion of how to identify the observers among your project’s stakeholders). Consider one or more of the following approaches to announce your project to all interested parties:

- An email to selected individuals or departments in your organization

- An announcement in your organization’s newsletter

- A flyer on a prominent bulletin board

- A formal kickoff meeting (if your project is large or will have broad organizational impact)

- A press release (if your project has stakeholders outside your organization)

Setting the Stage for Your Project Retrospective

A project retrospective (which we discuss in detail in Chapter 17) is a meeting in which you:

- Review the experience you’ve gained from the project.

- Recognize people for their achievements.

- Plan to ensure that good practices are repeated on future projects.

- Plan to head off problems you encountered on this project on future projects.

Start laying groundwork for the project retrospective as soon as your project begins to make sure you capture all relevant information and observations about the project to discuss at the retrospective meeting. Lay the groundwork by doing the following:

- Tell the team you’ll hold a project retrospective review when the project ends.

- Encourage team members to keep records of problems, ideas, and suggestions throughout the project and, when you prepare the final agenda for the project retrospective session, ask people to review these records and notes to find topics to discuss.

- Clarify the criteria that define your project’s success by reviewing the latest version of your project’s objectives with team members.

- Describe the details of the situation your project is designed to address before you begin the project work (if the project was designed to change or improve a situation) to enable you to assess the changes in these details when the project ends.

- Maintain your own project log (also called a RAID — for Risks, Actions, Issues, and Decisions — log; a narrative record of project issues and occurrences) and encourage other team members to contribute to the same (see Chapter 10 for more on the RAID log).

Relating This Chapter to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Table 13-1 notes topics in this chapter that may be addressed on the Project Management Professional (PMP) certification exam and that are also included in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 7th Edition (PMBOK 7).

TABLE 13-1 Chapter 13 Topics in Relation to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Topic | Location in This Chapter | Location in PMBOK 7 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

Finalizing team members’ project assignments | 2.2. Team Performance Domain | The steps discussed in both books are similar. | |

Recruiting resources from outside the organization | 2.4.3. Project Team Composition and Structure | Both sources discuss similar approaches for obtaining the personnel required to staff the project team. | |

Helping the team establish project and personal goals, individual roles, and team processes and relationships | 2.2. Team Performance Domain 2.2.4.4. Interpersonal Skills 4.2.6. Project Team Development Models | The steps for developing a team presented in both books are similar. This book highlights the individual and project elements that help to create a focused team. PMBOK 7 presents models for several of the team processes discussed here. | |

Managing conflicts | 2.2.4.4. Interpersonal Skills 4.2.7.1. Conflict Model 4.2.7.2. Negotiation | Both books note that project team success depends heavily on the ability of project managers to manage conflicts. PMBOK 7 lists multiple conflict resolution strategies. This book discusses how to apply conflict resolution strategies and presents examples. | |

Scheduling project meetings and progress reports | 2.5.4. Project Communications and Engagement 2.1.1. Stakeholder Engagement 4.4.3. Meetings and Events 4.6.7. Reports | Both books emphasize the need to plan regular project meetings and project progress reports in advance. This book lists information that should be addressed in these plans; see Chapter 15 for more on alternative communication approaches. |