Conclusion

Let's say you're trying to build the perfect OKR. Your objective is aspirational and lofty: Build the tallest building in the world.

This is the goal they set for the Empire State Building. The Empire State Building, impressively, was finished 12 days early and came in at $20 million under budget.

Another example of a perfect OKR is the one for the Golden Gate Bridge. The objective: Build the longest suspension bridge in the world. And, like the Empire State Building, the Golden Gate Bridge came in ahead of schedule and $1.3 million under budget.

Unfortunately, those are the exceptions. There's a long history of poor planning that spans major projects like this across the globe. Let's look at a couple of examples, like the Quebec Bridge.

The Quebec Bridge was budgeted for $6 million and ended up costing $23 million. It took 30 years to build and collapsed twice during the process.

The Sydney Opera House was budgeted for $7 million and came in at over $100 million. It was also 10 years late.

The James Webb telescope saw a similar fate, racking up a 1900% cost overrun. The telescope finished well behind schedule when it launched at the end of 2021.

My favorite example is the Second Avenue subway system in New York City. Originally, the system was budgeted at $99 million. It's now at $17 billion! Just a slight difference. It was proposed in 1929 and set to finish in 2029—100 years late.

In The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management by Bent Flyvbjerg, “the iron law of mega projects” is: they will come in over budget, over time, and under benefits, over and over again.

Flyvbjerg and his team studied 100 years of data on the subject, and found that 90% of projects came in over budget, over time, and under benefits again and again and again.

This phenomenon isn't exclusive to government projects, either. The researchers talked to students and asked them, “How long do you think it will take to finish your thesis?” They guessed 34 days, with the true outcome of 56 days.

If I'm being honest, I expected to finish this book much quicker than I did, as well.

$55 billion a year is lost to project delays, and there's a one‐in‐six chance that the project will be 200% over budget.

Take Justin Rosenstein, for example. Justin worked for Google. He has a brilliant mind for products. He co‐invented Google Chat. While he was at Google, he realized the extent of these planning problems and he built out some planning software. It didn't take off.

Later on, he went over to Facebook and he couldn't bring that software with him. He invented the Like button and built new planning software to make things more efficient.

Finally, he left Facebook to start his own company, called Asana, and he built the project planning software again. By his third time building planning software, you'd think he'd be a pro.

He did, too, so he predicted that the product would be launched within a year. And even the founder of a project planning company took three years to launch the company.

What is this phenomenon? And why does it happen? It's the planning fallacy, which is a tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and risk of future actions, and there are three reasons for it.

Optimism

The first reason is optimism. It's wishful thinking to focus on the best possible scenario and what you want to happen as opposed to past experience. This optimism is a double‐edged sword, because it can motivate you and inspire you to take on bigger and more ambitious challenges, but it can also lead to poor planning and missed objectives.

Bias

The second reason is a self‐serving bias. When something in the past has been successful, you tend to take the credit for yourself, but if it's a failure, you try to blame it on other things. You remember your wins in a more positive light than your losses. “It would have worked if it weren't for …”

Coordination Neglect

The third reason for the planning fallacy is coordination neglect. You would think that as a project starts to get late, your instinct would tell you to bring more resources into the fold to get it done and make it go faster. What researchers have actually found is that bringing more parties into a project late in the game can hurt the deadline more than it helps, because it takes time and bandwidth away from the current team to spin up the new members.

How Can You Get Around the Planning Fallacy?

Things are almost always going to take longer than you think, but you can use OKRs to help alleviate that aspect of the planning fallacy.

OKRs help you and your team focus. Instead of the five or 10 things you think you can do, you reduce that down to three to five that you can really get right. This focus enables a strong planning process and the permission to say no to distractions.

OKRs also bring transparency and provide accountability and collaboration, where everyone across the company (or a specific project) can see what's going on. What Flyvbjerg found is that you're more likely to incorrectly predict your own tasks. By leveraging OKRs' inherent transparency, you're able to involve stakeholders as checks and balances from the first step. When you look at other people's projects, you're more skeptical. You can say, “Hmm, that looks like it might take a little longer than you're planning.”

Finally, OKRs help you make data‐driven decisions. You're going to use these OKRs to track progress toward key milestones, and over time, you'll build up a data set of past projects that can inform future ones. This practice keeps you from blindly making timeline predictions, looking forward. Instead, you review past data to set realistic planning goals, based on projects that were similar.

Projects are almost always going to take longer than you think. So whether you have a really ambitious objective, like building the world's largest suspension bridge, or the next software release that you're trying to get out the door, lean on OKRs to bring focus, transparency, and data to your project.

As you continue building your OKR program, you produce a workforce that asks questions like “Does this align to our objective?” and “How is the work I'm doing impacting our organization's outcomes?” You are able to stretch toward ambitious objectives that align to your mission and values, and get crisp about both defining success and connecting output to outcomes.

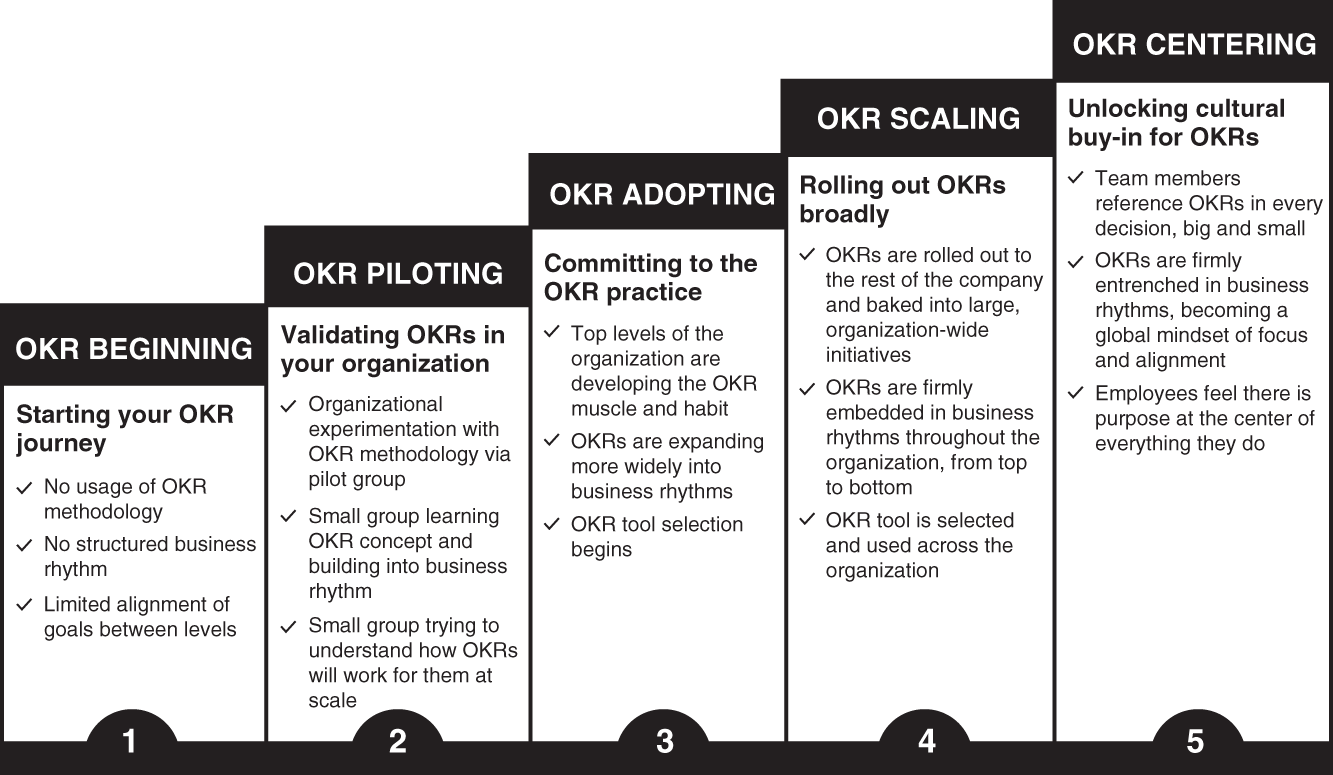

As OKRs become more entrenched in your organizational culture, you move up the OKR maturity curve.

My hope is that this book has answered the questions I set out to answer about OKRs as a goal‐setting framework and tool: what OKRs are, why you should implement them in your own organization, how you should roll them out, and when and where to begin.

But my true objective is that you will use the OKR knowledge in this book to turn your most ambitious visions and strategies into reality—on time, within scope, and as a team with a shared purpose.