Managing Effectively

Now this is not the end.

It is not even the beginning of the end.

But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

Winston Churchill

Welcome to the end of the beginning.1 This chapter considers the tricky subject of managerial effectiveness. Trying to figure out what makes a manager effective, even just trying to assess whether a manager has been effective, is difficult enough. Believing that the answers are easy only makes the questions that much more difficult. Managers, and those who work with them, in selection, assessment, and development, have to face the complexities. Helping to do so is the purpose of this chapter.

Before I scare you away, let me add that I had a good time writing this chapter. Perhaps the complexity led me into a kind of playfulness—about the inevitably flawed manager, the perils of excellence, what we can learn from happily managed families, and more. So I suspect, or at least hope, that you will have a good time reading this chapter.

We begin with the supposedly effective but in fact inevitably flawed manager. This leads us into a brief discussion of unhappily managed organizational families, due to the failure of (1) the person, (2) the job, (3) the fit, or (4) success. From here it is on to healthy managed organizational families, which can be found where reflection in the abstract meets action on the ground, supported by analysis, worldliness, and collaboration, all framed by personal energy on one side and social integration on the other. This takes us to three practical issues: selecting, assessing, and developing effective managers, asking along the way. “Where has all the judgment gone?” The chapter, and the book, close with a comment on “managing naturally.”

The Many Qualities of the Supposedly Effective Manager

Lists of the qualities of effective managers abound. These are usually short—who would take dozens of items seriously? For example, in a brochure to promote its EMBA program entitled “What Makes a Leader?” the University of Toronto business school answers: “The courage to challenge the status quo. To flourish in a demanding environment. To collaborate for the greater good. To set clear direction in a rapidly changing world. To be fearlessly decisive” (Rotman School, n.d., circa 2005).2

But this list is clearly incomplete. Where is native intelligence, or being a good listener, or just plain having energy? Surely these are important for managers, too. But fear not—they appear on other lists. So if we are to trust any of these lists, we shall have to combine all of them.

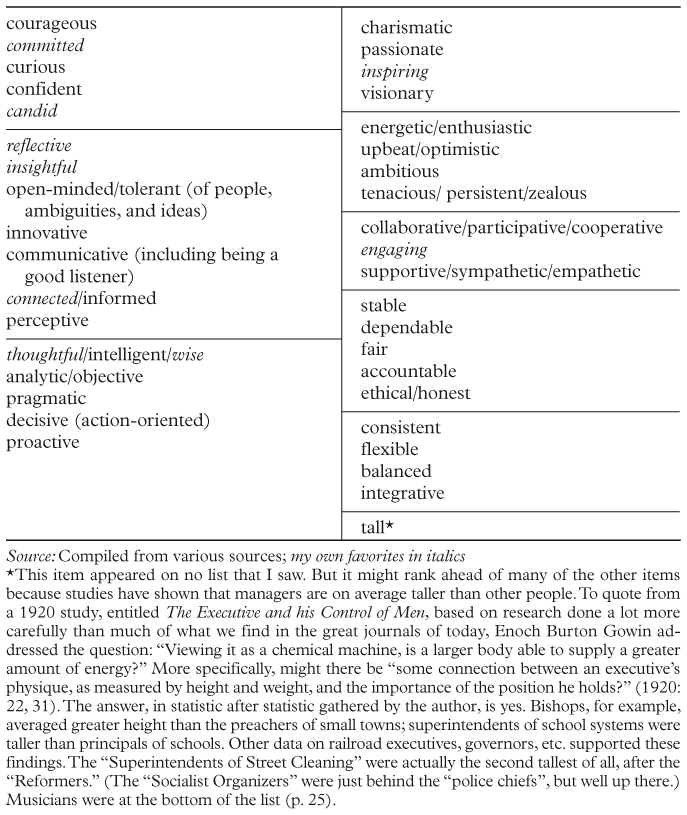

This, for the sake of a better world, I have done in Table 6.1. It lists the qualities from various lists that I have found, plus a few missing favorites of my own. This composite list contains fifty-two items. Be all fifty-two and you are bound to be an effective manager, if not a human one.

The Inevitably Flawed Manager

All of this is part of our “romance of leadership” (Meindl et al. 1985), that on one hand puts ordinary mortals on managerial pedestals (“Rudolph is the perfect person for the job—he will save us!”), and on the other hand allows us to vilify them as they come crashing down (“How could Rudolph have failed us so?”). Yet some managers do stay up, if not on that silly pedestal. How so?

Table 6.1 COMPOSITE LIST OF BASIC QUALITIES FOR ASSURED MANAGERIAL SUCCESS

The answer is simple: successful managers are flawed—we are all flawed—but their particular flaws are not fatal, at least under the circumstances. (Superman was flawed, too—remember Kryptonite?). Peter Drucker commented at a conference that “the task of leadership is to create an alignment of strengths, so as to make peoples’ weaknesses irrelevant.” He might have added “including the leader’s own.”

If you want to uncover someone’s flaws, marry them or else work for them. Their flaws will quickly become apparent. So will something else (at least if you are a mature human being who has made a reasonably good choice): that you can usually live with these flaws. Managers and marriages do succeed. The world, as a consequence, continues to unfold in its inimitably imperfect way.3

Fatally flawed are those superman lists of managerial qualities, because they are utopian. Much of the time they are also wrong. For example, managers should be decisive—who can argue with that? For starters, anyone who followed the machinations of George W. Bush, who learned the importance of being decisive by reading case studies in a Harvard classroom. The University of Toronto list calls this quality “fearlessly decisive.” Going into Iraq, President Bush certainly was that. As for some of the other items on that list, this president’s arch enemy in Afghanistan certainly “had the courage to challenge the status quo,” while Ingvar Kamprad, who built IKEA into one of the most successful retail chains ever, reportedly took fifteen years to “set clear direction in a rapidly changing world.” (Actually, he succeeded because the furniture world was not rapidly changing; he changed it.)

So perhaps we need to proceed differently.

UNHAPPILY MANAGED ORGANIZATIONAL FAMILIES

Tolstoy began his novel Anna Karenina with the immortal words “Happy families are all alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own particular way.”4 And so it may be with managers and their organizational families: they may have an unlimited number of ways to screw up, with ever more fascinating ones being invented every day,5 but perhaps few by which to succeed.

Tales of Two Managers

Let me bring two sets of two managers into the picture. Liz’s and Larry’s problems were rather normal. Both were smart, well-educated, modern managers. They worked near each other in the same company, one heading a major staff group, the other a major line operation. Liz leapt; Larry lingered. One made decisions too quickly, so that they often had to be remade; the other had difficulty making decisions at all, or else made them in ambiguous ways. The results were similar: people in their units felt excluded, confused, discouraged.

Beyond their own units, into the rest of the organization, Liz confronted while Larry connived. She often fought with her colleagues in the company—she knew better—except for the CEO, to whom she was deferential. Larry, in contrast, was careful not to upset anyone, so he hesitated to challenge when necessary.

Each, by the way, would probably recognize the other in this description. But would they recognize themselves? I need to add that although their respective managerial families were not particularly happy, these managers were not failures. None of these flaws was fatal. Things got done. They just could have been done more effectively—and happily.

The second tale comes from a study we did some years ago of a daily newspaper in a small Quebec town. It was owned, in succession, by two men of inherited wealth who went on to become quite famous as owners of Canadian media. Their approaches to managing were almost diametrically opposed. The first cared about the town, where he grew up but no longer lived, but he was passive with regard to the newspaper and so let its problems fester. The other, who followed him, was active all right; he cared about squeezing as much cost as he could out of the newspaper before selling it for a profit in a much reduced state. We concluded our study as follows:

Our tale of two Canadian tycoons is one of sharp contrasts in leadership. One was detached administratively but involved sentimentally; the other was detached sentimentally but involved administratively. One served the organization well so long as it didn’t have to adapt; the other served it well only while it was forced to adapt. The failings of the first brought in the second. In that sense they complemented each other, at least over time. But we are left wondering, in conclusion, if either (or both, in sequence) is what we really want in our society. Perhaps the message of [this study] is that healthy organizations and a healthy society need leaders who both act and care. (Mintzberg, Taylor, and Waters 1984:27)

To be true to Tolstoy, I am not going to propose a definitive list of the causes of managerial failures. This book is long enough. If you wish to have such a list, let me suggest you go back to Table 6.1 and reverse all the qualities there. For example, in place of decisive, put waffling, and in place of upbeat, downbeat. Or else keep the qualities as they are, but consider overdoing each. For decisive, you can put hasty; for upbeat, hyper. Indeed, just take these qualities and apply them in the wrong context. Be decisive without understanding the situation (that war in Iraq), or upbeat in managing a funeral home. To quote Skinner and Sasser in a Harvard Business Review article:

When the failure patterns [of managers] … are examined as a group, they are so numerous and so contradictory that they may seem frightening…. Managers get involved in too much detail—or too little. They are too cautious or too bold. They are too critical or too accepting…. They plan and analyze and procrastinate, or they blindly plunge ahead … without … analysis or plan. (1977:142)

What I offer here are some general groups of failure, within each of which reside a wide variety of possible disasters: personal failures, job failures, fit failures, and success failures. Each is discussed briefly, so that we can spend more time on the positive: healthily managed organizational families.

Person Failures

First are the failures that managers achieve all by themselves. Some managers are just in the wrong line of work. They may not want to manage—the reluctant ones—and so don’t relish the pace, the pressures, and much else that goes with the job. Perhaps they prefer to work alone, or in peer groups without responsibility for others.

Then there are the people who are just plain incompetent for the job: they are thoughtless, or don’t like people. These are surprisingly common, even among managers who have made it to senior positions. In a Fortune magazine article on “Why CEOs Fail,” Choran and Colvin offered two prime answers: “bad execution” and “people problems.” They commented on the former:

Keeping track of all critical assignments, following up on them, evaluating them—isn’t that kind of … boring? We may as well say it: Yes. It’s boring. It’s a grind. At least, plenty of really intelligent, accomplished, failed CEOs have found it so and you can’t blame them. They just shouldn’t have been CEOs. (1999:36)

Whether we call this “thin management” or macroleading (as discussed earlier), it seems to be becoming more common: managers who race down the “fast track” with the “quick fix.” (You can tell these managers by their propensity to use such language—the managerial “flavor of the month,” so to speak.) As CEOs in large corporations, these are the people especially inclined to diversify, merge, restructure, and downsize—all very fashionable, and often a lot easier than resolving complicated problems inside the company. Here is where we find the Syndrome of Superficiality out of control.

Beneath incompetence are managers who are imbalanced in their practice. In Chapter 3, I concluded that managers have to play all the roles on all the planes (information, people, action), in some sort of rough balance. As noted, too much emphasis on leading can favor style over substance, while too much acting can cause the job to explode centrifugally.6 Likewise, in Chapter 4, we discussed the problematic styles of excessive emphasis on the art, craft, or science of managing, which were labeled narcissistic, tedious, and calculating.

Many of the common managerial imbalances can be seen in terms of the conundrums discussed in Chapter 5. As noted there, a sure way to fail is to resolve any of these conundrums, such as the Riddle of Change by promoting too much change, or too little. Similarly, with regard to the characteristics of managing discussed in Chapter 2, too hectic a pace, too much fragmentation, an excess of oral communication, and so forth, can send the job over the edge (see Hambrick et al. 2005:481–482), as seems to be happening with increasing frequency now, thanks to the Internet.

All of this is not to make the case for perfect balance in managing. That also can be a form of imbalance, with the manager exhibiting no focus, no character, no style of his or her own.7

Job Failures

Sometimes a person is well suited to managing and well balanced in his or her approach to the job, but that job is simply undoable—unmanageable—and so the person fails.

In the last chapter, we discussed unnatural managerial jobs—ones that should not exist. They have been created to cut spans of control, or to impose some kind of artificial managerial oversight, often in arbitrarily designated geographic regions. To repeat an earlier comment, there is nothing so dangerous as a manager with nothing to do.

In Chapter 4, we also discussed split managerial jobs that are difficult to do, because the manager is pulled in different ways by different demands. John Tate of the Canadian Justice Department was pulled between advising the minister, serving as a policy expert, and managing the department. Marc, the hospital Executive Director, had to be the tough advocate externally yet the reconciler of the demands of other advocates internally. Can both be done by one person?

A manager can also fail because the job is embedded in an organization or an outside context that makes it impossible. Think of the officer in charge of rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, or the Vice President of Anything at Enron as it went down. How about being the sales manager of a company with shoddy, unsellable products? Don’t blame the manager, except for taking the job, but do recognize that here, too, the possibilities for failure are endless.

Fit Failures

Next are the potentially competent, balanced managers in perfectly doable jobs, just not the jobs for them. So they become unbalanced and therefore incompetent—misfits quite literally.

Here, again, the stories are legion, some of them stemming from the fallacy of professional management—that any properly educated manager can manage anything. Earlier, for example, we had the question of whether school systems should be run by retired military officers, leading to the question of whether retired schoolteachers should run the army. I also recall a business school that named a dean who had been running a trucking company. He claimed that managing professors was just like managing truck drivers. So most of the competent truck driver professors left.

There is also the Peter Principle discussed in the last chapter, about managers rising to their level of incompetence. They should have been promoted once less. Managerial experience at one level in a given hierarchy does not necessarily suit someone for managing at another level.

The Quandary of Connecting, discussed in Chapter 5, suggests that the very fact of becoming a manager can render a worker incompetent in the new job. Bump this up the hierarchy and a perfectly competent junior manager can be rendered an incompetent senior manager as he or she gets promoted further and further from his or her own sphere of knowledge and competence. A fault that was tolerable before—hubris all too often these days—becomes fatal.

Fit can also became misfit when conditions change, so that positive qualities turn into serious flaws. For example, an organization in crisis may find itself being managed by someone more suitable to managing in a steady state. Or a great turnaround artist is brought into an organization that is running perfectly well in steady state. What ain’t broke thus gets fixed, to paraphrase that old saying. How about the army officer trained for conventional warfare who finds himself facing guerrillas, or the manager in the public sector who finds herself running a unit that has been privatized? The situation changes; perhaps the manager cannot (Vail 1989:122–123).

But be careful here: evident matches can prove to be misfits, too. Sometimes matches of opposites work better than matches of likes—what we might call intentional misfits. Does a machine organization need a highly cerebral chief? Maybe it needs one who can open up its narrow tendencies, just as a wild and woolly adhocracy can sometimes benefit from an organized chief who keeps a lid on the madness. As Lombardo and McCall put it, “the most effective leaders we have observed seem to act in a counter-intuitive fashion, going against the grain of the environment…. [For example, in] the most predictable of the divisions, the effective VPs introduce a note of strategic unpredictability” (1982:58).

Success Failures

A special case of the last is the failure that derives from success. A company grows too large for its founding entrepreneur, or hubris sets into the management of a research establishment that has had too much success.

In an intriguing book called The Icarus Paradox,8 which could have also been titled The Perils of Excellence, Danny Miller (1990) demonstrated how organizations can be changed by their own success: their strengths become weakness, their successes turn into failures. Miller described four main “trajectories” by which this happens, which in fact correspond rather closely to the four forms of organization introduced in Chapter 4. For example, “growth-driven, entrepreneurial Builders … managed by imaginative leaders … [become] impulsive, greedy imperialists, who … [expand] helter-skelter into businesses they know nothing about.” Or “Pioneers [adhocracies] with unexcelled R&D departments, flexible think-tank operations, and state-of-the-art products, [become] utopian Escapists, run by cults of chaos-living scientists who squander resources in the pursuit of hopelessly grandiose and futuristic inventions” (pp. 4–5).9 So, too, can this happen with managers themselves: the doers becoming overdoers; the linkers become gadflies; the leaders become cheerleaders.

Under the Icarus Paradox, a kind of arrogance of attribution sets in: “We [or I] must be wonderful because our organization is so successful.” Maybe that was true, but believing your organization is wonderful can undermine its effectiveness because part of that wonderfulness may have been a certain humility, which engendered an open spirit. Established managers who take themselves too seriously—or, perhaps more commonly, newly appointed managers who had no role in a success they associate with themselves—risk riding over the edge of confidence, into arrogance.

Is this inevitable? Nothing is inevitable. There are plenty of managers who maintain their good sense—their own internal balance. But there are enough of the others to suggest how often success becomes a curse.

In a discussion of “failure as a natural process,” Spiros Makridakis wrote: “In the biological world failure is synonymous with death and is considered a natural event…. Failure seems to be as natural likewise among organizational systems” (1990:207). Unfortunately, however, it is not necessarily tied to death, as we have found out about banks and automobile companies in this new millennium. Likewise, failed managers often live on, not only in life but in their jobs, there to sustain the misery.

To conclude, many evident pitfalls accompany the practice of managing. Someone once defined an expert as someone who avoids all the many pitfalls on his or her way to the grand fallacy. Not only experts, but managers too.

HEALTHILY MANAGED ORGANIZATIONAL FAMILIES

OK, enough about failure. We can dwell on that forever. What matters is success. And there is no shortage of that, more or less. As the story of Liz and Larry suggests, flawed managers can perform well enough. They avoid enough of the pitfalls without finding their way to the grand fallacy. In fact, many of the twenty-nine managers of this study were more than good enough: they managed to create or sustain healthy organizational families. How did they do that?

Wouldn’t it be nice if I could now offer the answer in five easy steps? I can’t, but I can offer a framework to consider it.

Lewis, Beavers, Gossett, and Phillips, in the introduction to their book No Single Thread: Psychological Health in Family Systems, commented: “There is considerable literature on the pathological family types, but a ‘scarcity of data’ on the healthy family” (1976:xvii). There is likewise a scarcity of data, amid a plethora of speculation, about how organizations are managed effectively.

I thought initially that I could proceed here by getting clues from the literature on families, out of the fields of psychology, psychiatry, and the like. I quickly dropped that idea as futile, and settled on the framework that is presented in Figure 6.1 and discussed in this section. Then a colleague suggested I look at the Lewis et al. book just cited. I was struck by its parallels with the framework I had developed, so much so that I was able to match a quotation from that work with each of the dimensions of this framework, as you will see. Even my conclusion about managerial effectiveness having to be considered in context is paralleled by the comment of Lewis et al. that “family strengths may be understood better through the study of the total family system than a study of the individual” (p. 216). Perhaps these parallels are coincidental, although I think it more likely that different kinds of social systems (families, organizational units, etc.) share some characteristics.

A Framework for Effectiveness

What I offer here is no formula, no theory, not even a set of propositions so much as a framework by which to think about managerial effectiveness in context. As shown in Figure 6.1, at the center are five “threads,” to use Lewis et al.’s word, or “managerial mindsets” as we call them, ranging from the more personal to the more social—labeled reflective, analytic, worldly, collaborative, and proactive. (See Gosling and Mintzberg 2003 and Mintzberg 2004b: Chapter 11. These mindsets have been used to organize the modules of our International Master’s in Practicing Management [www.impm.org], as will be seen later.) Two additional threads are shown: at one end, that of being personally energetic; at the other, that of being socially integrative.

Figure 6.1 A FRAMEWORK TO CONSIDER MANAGERIAL EFFECTIVENESS IN CONTEXT

This may seem like my own short list of managerial qualities, but it goes beyond the lists discussed earlier in two ways. First, these threads are rooted more in the practice of managing rather than in the nature of the person practicing it. They were derived from the roles managers perform, as discussed in Chapter 3. For example, the analytic thread corresponds to the role of controlling on the information plane, the collaborative thread to the roles of leading and linking on the people plane, and the proactive thread to the roles of doing and dealing on the action plane.

Second, this is a framework rather than a list, in that its threads weave together. Personal energy on the left drives the five mindsets, and social integration on the right brings them together. Within the mindsets themselves, reflection above, in the abstract, and proaction below, on the ground, frame the exercise of analysis, worldliness, and collaboration.

Each thread is discussed in turn, although it is important to note that they have to be considered together, as guidelines to think about managerial effectiveness. Here, too, Lewis et al. explain it well:

We found no single quality that optimally functioning families demonstrated and that less fortunate families somehow missed…. It was [the presence and interrelationship of a number of variables] that accounted for the impressive differences in style and patterning among the optimal families…. Health at the level of family was not a single thread … competence must be considered as a tapestry. (pp. 205–206)

The discussion of these threads serves also to bring together some of the key points that have come out throughout this book.

The Energetic Thread

“Although [effective] families differ in the degree of energy displayed, they all demonstrated more constructive reaching out than did patently dysfunctional families” (Lewis et al. 1976:208–209). Effective managers likewise differ in the energy they display, as do the units they manage, but we can likely expect a high degree of energy from both, and certainly a good deal of “reaching out.”

If one thing is evident about the hectic pace, the orientation to action, the variety and fragmentation of the activities of managing, it is the enormous amount of energy that effective managers bring to their work. This is no job for the lazy.

Energy is a largely personal thread in our tapestry (perhaps it is the loom), anchoring one end of our framework. Of course nothing in management is ever wholly personal. As Peter Brook, legendary director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, wrote in his book The Empty Space (1968), the audience energizes the actor as much as the actor energizes the audience.

This thread may help us understand how managers deal with two of the conundrums. The Quandary of Connecting asks how managers can keep informed when they are fundamentally removed; the Riddle of Change asks how they can drive change while maintaining stability. This kind of energy is necessary to connect, to change, and to maintain stability.

The Reflective Thread

“In approaching problems within the family, [the healthy ones] explored numerous options; if one approach did not work, they backed off and tried another. This was in contrast to many dysfunctional families in which a dogged perseverance with a single approach was noted” (Lewis et al. 1976:208). This sounds much like the reflectiveness discussed in Chapter 5. My own observations suggest that a remarkable number of effective managers are reflective: they know how to learn from their own experience; they explore numerous options; and they back off when one doesn’t work, to try another.

To be reflective also suggests a certain humbleness, not only about what managers know, or think they know, but also about what they don’t. That is why I have been so critical of heroic management in this book.

As I discussed in Managers Not MBAs, reflecting means “wondering, probing, analyzing, synthesizing, connecting—‘to ponder carefully and persistently [the] meaning [of an experience] to the self’” (Mintzberg 2004b:254, quoting Daudelin 1996:41). In Latin, to reflect “means to refold, which suggests that attention be turned inward so that it can then turn outward, to see a familiar thing in a different way” (p. 301; this metaphor is from Jonathan Gosling). Reflecting goes beyond sheer intelligence, to a deeper wisdom that enables managers to see insightfully—inside issues, beyond the usual perceptions. Effective managers think for themselves. (See the accompanying box on “The Best Management Book Ever.”)

The Best Management Book Ever

In a family of novel programs that we have created, which focus on practicing managers learning from their own experience (to be discussed later in this chapter), each day begins with what we call “morning reflections,” in three stages.

First, each manager writes quietly in his or her “Insight Book”—an empty book except for the person’s name on it—about whatever seems relevant to his or her learning: ideas, thoughts overnight, concerns about a comment made on the previous day, and so on. After about ten minutes, the managers—sitting in small groups at round tables—share their insights for another fifteen minutes or so. Then it is into plenary, sometimes in a big circle, to draw out the best of the insights from the tables. This last stage is scheduled for about twenty minutes, but it often runs for over an hour. We let it go because this is the glue that bonds much of the learning together, across the entire program.

Lufthansa has sent teams of managers to one of these programs, our International Masters in Practicing Management (www.impm.org), from its inception in 1996. Each year it holds a meeting in-house, where its graduates welcome the new participants. One year Silke Lenhardt, an early graduate, held up her Insight Book and announced: “This is the best management book I ever read!” Shouldn’t all managers’ best management book be the one they have written from their own experience?

As noted repeatedly, much managing is hectic—“one damn thing after another.” As a consequence, many managers desperately need to step back and reflect quietly on their own experience. As Saul Alinsky was quoted in Chapter 5, people cannot get the meaning of their experiences without reflection.

Reflection can be an effective antidote to a number of the conundrums: the Clutch of Confidence, the Predicament of Planning, the Syndrome of Superficiality, the Quandary of Connecting. Effective managers figure out how to be reflectively thoughtful in a job that naturally discourages it. In a job that rarely allows managers uninterrupted time on complex issues, reflective managers attend to such issues intermittently and incrementally, giving themselves time to learn as they proceed. As H. Edward Wrapp put it, they “muddle with a purpose” (1967:95; see also Sayles 1964:259).

Table 6.2 reprints a set of self-study questions adapted from my earlier book on managerial work. Some of these questions may seem simple, even rhetorical, but they can help stimulate reflection. (One manager wrote to me that he “tries to re-read [the questions] every few days. Each time I seem to find a new idea to apply.”)

The Analytic Thread

In discussing the art-craft-science triangle in Chapter 4, I made the point that while there has been no shortage of managers who have overemphasized the analytic dimension, inadequate attention to it can lead to a disorganized style of managing. And this brings us back to the Enigma of Order: how can the disorderliness of managing produce the necessary order for the unit being managed?

Looking for the key to effective managing in the light of analysis may be misguided, but expecting to find it in the obscurity of intuition makes no more sense. Once again, what makes sense is a certain balance: recognizing that managing requires attention to the two fundamental ways of knowing introduced earlier, one formal and explicit, the other informal and tacit. That is why the terms “calculated chaos” and “controlled disorder” apply so well to managerial work. Interestingly, in much the same way, Lewis et al. described the most dysfunctional families as presenting “chaotic structures” and the midrange families “rigid structures,” while the “most competent families presented flexible structures” (p. 209).

What does analytic mean in light of this need to be flexible? Several words can apply. One already suggested is to be orderly, at least in helping bring order to those who need it. Another is to be logical—to be clear and articulate—although judgment, as used later in this chapter, is probably a better word. Finally, Wrapp has described the effective manager as “skilled as an analyst, but even more talented as a conceptualizer” (1967:96, italics added).

The danger of overreliance on analysis came out especially in two of the conundrums: the Labyrinth of Decomposition, where so much surrounding the manager is chopped into nice, neat, artificial categories; and the Mysteries of Measuring, where managers have to deal with that soft underbelly of hard data. As I noted in The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (1994b:386–387), there exists in organizations a “formalization edge,” over which managers can easily fall. Too much analysis or formalization and the essence of an issue can be lost. Read, for example, those easy prescriptions about leadership and all those documents abut goals, missions, visions, plans, and on and on.

Table 6.2 SELF-STUDY QUESTIONS FOR MANAGERS

| 1. | Where do I get my information, and how? Can I make greater use of my contacts? How can I get others to provide me with the information I need? Do I have sufficiently powerful mental models of those things I must understand? |

| 2. | What information do I disseminate? How can I get more information to others so they can make better decisions? |

| 3. | Do I tend to act before the information is in? Or do I wait so long for all the information that opportunities pass me by? |

| 4. | What pace of change am I asking my unit to tolerate? Is this balanced with the needed stability? |

| 5. | Am I sufficiently well informed to pass judgment on the proposals submitted to me? Can I leave final authorization for more of these proposals to others? |

| 6. | What are my intentions for my unit? Should I make them more explicit to guide better the decisions of others? Or do I need flexibility to change them at will? |

| 7. | Am I sufficiently sensitive to the influence of my actions, and my managerial style in general? Do I find an appropriate balance between encouragement and pressure? Do I stifle initiative? |

| 8. | Do I spend too much time, or too little, maintaining my external relationships? Are there certain people whom I should get to know better? |

| 9. | In scheduling, am I just reacting to the pressures of the moment? Do I find the appropriate mix of activities, or do I overconcentrate on what I find interesting? Am I more efficient with particular kinds of work at special times of the day or week? |

| 10. | Do I overwork? What effect does my workload have on my efficiency and my family? Should I force myself to take breaks or reduce the pace of my activity? |

| 11. | Am I too superficial in what I do? Can I really shift moods as quickly and frequently as my schedule requires? Should I decrease the amount of fragmentation and interruption? |

| 12. | Am I a slave to the action and excitement of my job, so that I am no longer able to concentrate on issues? Should I spend more time reading and probing deeply into certain issues? |

| 13. | Do I use the different media appropriately? Do I know how to make the most of written communication and e-mail? Am I a prisoner of the pace of e-mail? Do I rely excessively on face-to-face communication, thereby putting all but a few of my reports at an informational disadvantage? Do I spend enough time observing activities firsthand? |

| 14. | Do my obligations consume all my time? How can I free myself from them to ensure that I am taking the unit where I want it to go? How can I turn my obligations to my advantage? |

Source: Adapted from Mintzberg (1973:175–177)

So while Skinner and Sasser (1997) in their Harvard Business Review article may have had good reason to claim that effective managers “employ the practice of analysis with great effect” and “use analytic tools with … discipline and consistency,” when they concluded that effective managers are “above all else analyzers” (pp. 148, 143), in my opinion they were just plain wrong. An overemphasis on analysis in managing has driven out too much judgment in organizations, in the processes breeding a good deal of dysfunction.

The Worldly Thread

“There is another complex family variable that involves respect for one’s own world view as well as that of others” (Lewis et al. 1976:207).

We hear a great deal these days about managers having to be global; it is far more important that they be worldly. To be global implies a certain homogeneity. The word suggests conformity, “everyone subscribing to the same set of beliefs, style, and values. Forget your background, your origins, your roots; become modern, contemporary, part of the emerging ‘globe’” (Mintzberg and Moore 2006). Is this what we want from our managers? It seems to me that we have too much of it already.

Reflectiveness was described earlier as very much the opposite: to think for oneself. What may best promote this, and bring the judgment so desperately needed back into managing, is a certain worldliness.

Worldly is identified in the Pocket Oxford Dictionary as “experienced in life, sophisticated, practical.” An interesting mixture of words. And perhaps as close as a set of words can get to what many of us want from our managers, as true leaders.

All managers function on a set of edges between their own world and those of other people. To be worldly means to get over these edges from time to time, into those worlds—other cultures, other organizations, other functions in their own organization, above all the thinking of other people—so as to understand their own world more deeply. To paraphrase a line by T. S. Eliot that has been overused for good reason, managers should be exploring ceaselessly in order to return home and know the place for the first time. That is the worldly mindset.

“How can you possibly drive in this traffic?” asked an American manager of an Indian professor after she had just arrived in Bangalore to attend the module of our IMPM program on the worldly mindset. “I just join the flow,” he replied. Worldly learning had begun! There is a logic to other people’s worlds—order to what may seem to us like chaos. Understand it and you will be a better manager—and more of a human being.

To appreciate other people’s worlds does not mean to invade their privacy or “mind-read” them, which can be condescending. Lewis et al. found these to be “destructive characteristics,” seen only in “the most severely dysfunctional families” (p. 213). In the less healthy families, they found pressures for conformity, similar to those of globalization in business. In place of these, the healthy families exhibited a characteristic they called “respectful negotiation”:

Because separateness with closeness was the family norm, differences were tolerated and conflicts were approached through negotiation, which respected the rights of others to feel, perceive, and respond differently. There was no tidal pull toward a family oneness that obliterates individual distinctions. (p. 211)

If analysis is closer to science on our triangle, then worldliness is closer to craft, rooted in tangible experience and tacit knowledge. So it is shown to the right on Figure 6.1, while analysis—based on explicit knowledge—is shown to the left, where science appeared on the triangle.

One theme that was evident in all the conundrums discussed in Chapter 5, especially the Ambiguity of Acting (how to act decisively in a complicated, nuanced world), is the need for managers to have a sense of nuance. Worldly managers who come to know their own place for the first time because they have gained insight into other places may best be able to deal with the conundrums.

The Collaborative Thread

“The trend toward an egalitarian marriage was in striking contrast to both the more distant (and disappointing) marriages of the adequate families and the marital pattern of dominance and submission that so often was seen in dysfunctional families” (Lewis et al. 1976:210).

As we move along our tapestry, the collective or social aspects of managing become more prominent. Collaboration, of course, takes us to managing the relationships with other people, in the unit and beyond.

Hiro Itami, who initially directed the IMPM module held in Japan on the collaborative mindset, told the participating managers: “Management is not to control people. Rather it is to let them collaborate.” Hence, he positioned the module as “managing human networks.” Kaz Mishina, who directed that module subsequently, expressed it as “leadership in the background”—namely, “letting as many ordinary people as possible lead” (in Mintzberg 2004:308).

Collaboration is not about “motivating” or “empowering” people in the unit, because as noted earlier that may just reinforce the manager’s authority. It is rather about helping them, and others outside the unit, work together, in the spirit of the Lewis et al. quotation.

In the “engaging” style of managing introduced in Chapter 4, the manager engages him- or herself in order to engage others, as described in Table 6.3. There is a sense of respecting, trusting, caring, and inspiring, not to mention listening. These are the words that struck me repeatedly in my days with many of the twenty-nine managers, including Fabienne Lavoie in the nursing ward, Stephen Omollo in the refugee camps, John Cleghorn in the bank branches, and Catherine Joint-Dieterle in the museum. To draw further from the Lewis et al. book, “Healthy families were open in the expression of affect. The prevailing mood was one of warmth, and caring. There was a well developed capacity for empathy” (p. 214). Managing seems to work especially well when it helps to bring out the energy that exists naturally within people.

It is important to appreciate that there is nothing especially magical about this thread, no great characteristic of leadership. Like the other threads, it is perfectly natural, much as is living in a family that functions effectively.

Collaboration also extends beyond the unit, to other managers of the organization and other people outside it. Sometimes these relationships are formalized—after all, we use the word collaboration for joint ventures and alliances—but often they are informal, as in the networking that all managers do.

Table 6.3 ENGAGING MANAGEMENT

| • | Managers are important to the extent that they help other people to be important. |

| • | An organization is an interacting network, not a vertical hierarchy. Effective managers work throughout; they do not sit on top. |

| • | Out of this network emerge strategies as engaged people solve little problems that can grow into big initiatives; implementation, so-called, also feeds formulation. |

| • | To manage is to help bring out the positive energy that exists naturally within people. Managing thus means engaging, based on judgment, rooted in context. |

| • | Leadership here is a sacred trust earned from the respect of others. |

Source: Compiled from various sources; adapted from Mintzberg (2004:275)

As we discussed in “Managing beyond the Manager” in Chapter 4, the past century has seen a steady shift from managing as controlling to managing as engaging. We hear more and more about knowledge workers, contract work, networked and “learning” organizations, teams and task forces, while many “subordinates” have become colleagues and many suppliers have become partners. Accompanying this has been a steady devolution of power from managers to nonmanagers, with a corresponding shift in managerial styles toward convincing from controlling, linking from leading, inspiring from empowering. But these trends are not new. Mary Parker Follett wrote in 1920 that “the test of a foreman is not how good he is at bossing, but how little bossing he has to do.”

Collaboration also offers a way to deal with some of the conundrums. In particular, delegation becomes less of a dilemma when a manager naturally inclined to collaborate keeps people in the unit well informed. And connecting becomes less of a quandary when managers who collaborate get better connected, and so became more informed.

The Proactive Thread

“There was little that was passive about healthy families. The family as a unit demonstrated high levels of initiative in responding to input” (Lewis et al. 1976:208–209).

All managerial activity, as noted several times and shown in Figure 6.1, is sandwiched between reflection in the abstract and action on the ground—that refl’action mentioned earlier. Too much reflection and nothing gets done; too much action and things get done thoughtlessly. So here we consider action on the ground, which encompasses the managerial roles of doing and dealing.

I have saved this for last among the five mindsets because while reflectiveness is largely personal, proactiveness is fundamentally social: there can be no managerial action without the involvement of other people. Managing is a social process. Managers who try to go it alone typically end up overcontrolling—issuing orders and deeming performance in the hope that authority will ensure compliance. This may work sometimes, but it hardly taps human potential, especially among thinking people.

I use the term proactive here rather than active to designate that this thread is about managers seizing the initiative: initiating action instead of just responding to what happens, taking steps to circumvent obstacles, seeing themselves in control.10 As I noted earlier, especially in Chapter 4, effective managers, no matter where in the hierarchy and how seemingly constrained, grab whatever degrees of freedom they can get and run vigorously with them. To quote Isaac Bashevis Singer in what could be a motto for the effective manager: “We have to believe in free will; we’ve got no choice.” An additional distinction of importance here comes from Mary Parker Follett: “The leader should have the spirit of adventure, but the spirit of adventure need not mean the temperament of the gambler. It should be the pioneer spirit which blazes new trails” (1920:80; see also Mintzberg 2009b).

Effective managers thus do not act like victims. They are “agents of change,” not “targets of change” (Hill 2003:xiii). They go with the flow (like that traffic in Bangalore), but they also make the flow (as, of course, do those drivers in Bangalore). Managing is for people who relish the pace, the action, and the challenges, from wherever they come, and to wherever they can take them.

The most evident conundrum here is the Ambiguity of Acting: how to act decisively in a complicated, nuanced world? Being worldly can certainly help, as can being reflective—both of them in order to appreciate the nuances. So, too, can functioning in a way that encourages learning. The word proactive may evoke the image of driven change from the top down—decisive, deliberate, dramatic. But I suspect that a good deal of proactive managing works in precisely the opposite direction: it is experimental, incremental, emergent, and flows from the bottom up and the middle out. Senior managers need to facilitate the proactive changes of others at least as much as initiate their own changes.

And don’t forget the Riddle of Change. Effective managers may drive change, but they also have to maintain stability, which can require just as much proactiveness, as we saw in those Red Cross refugee camps.

The Integrative Thread

Let me repeat, from the outset of this discussion, what may be Lewis et al.’s most important conclusion: “health at the level of family was not a single thread … competence must be considered as a tapestry” (p. 206). Managing is a tapestry woven of the threads of reflection, analysis, worldliness, collaboration, and proactiveness, all of it infused with personal energy and bonded by social integration.

In looking “at the essentials of leadership,” Follett designated “of the greatest importance … the ability to grasp the total situation…. Out of a welter of facts, experience, desires, aims, the leader must find the unifying thread. He must see a whole, not a mere kaleidoscope of pieces,” in order to “organize the experience of the group” (1920:168). Moreover, the manager “must see the evolving situation, the developing situation” (p. 169); in other words, managing means integrating on the run. Follett, writing long ago, referred to “he,” but this applies not only to “she” but also to “they”—all sorts of people, working collaboratively, managers and nonmanagers alike.

But how to integrate? There is no easy answer, but Follett provided a lovely clue:

In business we are always passing from one significant moment to another significant moment, and the leader’s task is pre-eminently to understand the moment of passing. The leader sees one situation melting into another and has learned the mastery of that moment. (p. 170)

The mastery of that moment! Kaplan described court vision that enables “a basketball player breaking down court, to see the play developing and know[s] how to position himself in relation to” others (1986:10). Wayne Gretzky, the legendary hockey player, said it more simply: “I skate to where the puck is going to be.”

Integrating requires mastering across moments, too. Managing is about achieving a dynamic balance, as has been stressed throughout this book: across the information, people, and action planes of managing, while blending the various roles; reconciling the concurrent needs for art, craft, and science; juggling many issues all the time, keeping most in the air while giving each a boost as it comes down.

The word analysis seems clear enough; the word synthesis, in contrast, is characterized by its very obscurity. What does it mean to achieve synthesis, and would we even know it when we see it?11 A key purpose of managing is to strive for synthesis, continuously, without ever reaching it, or even quite knowing how close one is.

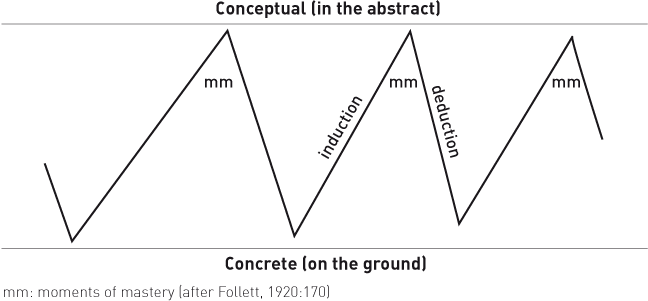

It is through the interplay of reflecting and acting—our first and last mindsets—that managers strive for synthesis. As discussed in Chapter 5, managers not only work deductively, and cerebrally, from reflection to action—formulation to implementation, the conceptual to the concrete—as is so commonly described. They also work inductively, insightfully, from action to reflection, the concrete to the conceptual, as they learn from experience. Above all, as shown in Figure 6.2, they cycle back and forth between these two, passing those moments of mastery.

Don’t assume, however, that because induction and deduction proceed iteratively, reflecting and acting are necessarily separate and sequential. To return to Karl Weick’s point raised in Chapter 3, thinking is not disengaged from acting in managing, but is an intrinsic part of it: managers think while they act; “managerial activities can be done more or less thinkingly” (1982:19).

This discussion has focused mostly on integration by the manager him- or herself. But integration goes far beyond the individual manager, as discussed at the end of Chapter 4. Harnessing the “collective mind” is one of the great challenges facing contemporary organizations—for example. in crafting strategies and establishing culture and community.

Of course, no matter how many people craft a strategy, it may take one particularly integrative brain to draw that learning into some sort of strategic vision. We expect this to be a senior manager, but in fact anyone with a capacity for synthesis can be that visionary, sometimes even “the wisdom of crowds” (Surowiecki 2004).

Figure 6.2 INTEGRATING THROUGH ITERATION

The conundrums associated with integration seem once again to be rather obvious. The Labyrinth of Decomposition has been discussed here; the Predicament of Planning questions how a manager can think ahead—which also means to think integratively—in such a hectic job. Weick’s notion of acting thinkingly offers help in this regard.

To conclude this discussion of healthily managed organizational families, it is worth repeating that these threads work only when they are woven into a coherent tapestry, whatever form that takes. There is no Holy Grail of managerial effectiveness.

SELECTING, ASSESSING, AND DEVELOPING EFFECTIVE MANAGERS

Managers as well as the people who work with them are generally concerned about how to select managers who will be effective, how to access whether they are actually being effective, and how they can be developed for greater effectiveness. The findings of this book are used to consider each of these in turn.

Selecting Effective Managers

This subject has received considerable attention, which does not need to be repeated here. I would just like to add a few thoughts of my own.

Choosing the Devil You Know The perfect manager has yet to be born. If everyone’s flaws come out sooner or later, then sooner is better. So managers should be selected for their flaws as much as for their qualities. The inclination has instead been to focus on people’s qualities, sometimes a single one that blinds us to everything else. “Sally’s a great networker” or “Joe’s a visionary,” especially if the failed predecessor was a lousy networker or devoid of strategic vision. No one should ever be selected for a managerial job without making every reasonable and ethical effort to identify his or her flaws—the devil in the candidate.

There is, by the way, one fatal flaw that is wholly common today, yet rather easy to ferret out. Any candidate for a chief executive position who insists on compensation far in excess of others in the company, and, worse, who insists on special protection in the event of failure or firing, should be rejected out of hand. After all, hasn’t this candidate already pronounced on how important it will be to “build the team,” treat “people as the company’s greatest asset,” take “the long view”? Imagine how instituting this would change the corporate landscape.

And then these flaws should be carefully judged against the managerial job and situation in question, to avoid surprises, especially from flaws that might later prove fatal. Since flaws are that in context only, performance in a previous managerial job may give no indication of a looming problem in the next one. Of course, figuring this out may be no easy matter: people’s qualities are often misjudged, as are the criteria needed for success in a particular job. But there is a surprisingly simple yet rarely used way to mitigate this.

Voice to the Managed Managing happens on the inside, within the unit (through the roles of controlling, leading, doing, and communicating), and on the outside, beyond the unit (through the roles of linking, dealing, and communicating). Yet it is usually people outside the unit who control the selection of its manager, whether that be the board in the choice of chief executive or senior managers in the case of junior ones. What sense does this make, especially when it is so much easier to impress outsiders, who have not had to live with the candidates on a daily basis? Charm may be one criterion for selection, but hardly the main one. As a consequence, too many organizations these days end up with managers who “kiss up and kick down”—overconfident, smooth-talking individuals who have never exhibited the most basic form of leadership (see Tsui 1984; also Luthans, Hodgetts, and Rosenkrantz 1988:66ff. and 160ff.).

If one simple prescription could improve the effectiveness of managing monumentally, it is giving voice in the selection processes to those people who know the candidates best—namely, the ones who have been managed by them. Some companies also have outside candidates’ interviewed by members of the unit, to get their sense of the fit. This could be especially pertinent in the selection of chief executives, where blind optimism seems to be so prevalent.

Can people be trusted to assess candidates for the position of their own manager? There is no doubt about the possibility of bias. But is that worse than trusting inadequately informed outsiders? I am not calling here for the election of managers, only for a balanced assessment by insiders and outsiders together. Indeed, this is common practice in hospitals, universities, and law offices.

There is one famous company, for decades the leader in its field, whose chief executive is elected by a closed vote of its senior managers. I have asked many groups of businesspeople, all of whom know this company, to guess which it is. Rarely does anyone get it. The answer is McKinsey & Company, whose executive director is elected to a three-year term by a vote of the senior partners. This seems to have worked well for McKinsey. Has any McKinsey consultant ever proposed it to a client?

Considering an Outside Insider There seems to be some tendency of late, at least for senior positions, to favor outsiders: the new broom that can sweep clean. Unfortunately, the sweeping may be done by the devil the selection committee does not know, while the sweeper may not know enough to distinguish the real dirt. So the danger arises, especially in this age of heroic leadership, that the new broom will sweep out the heart and soul of the enterprise. Perhaps we need a little more attention in selection processes to the devils we do know, because they know the dirt.

In fact, selection committees can get the fresh look of an outsider, unbeholden to the powers within, as well as the knowledge of an insider, by choosing both: someone who quit in disgust—an outside insider. Such a person knows the situation, voted with his or her feet against it, and so may be ideal to drive a turnaround: a new broom that knows the old dirt. Moreover, there will be insiders who can assess this person’s qualities and flaws. Steve Jobs of Apple comes to mind here: he didn’t quit in disgust—he was fired from the company he built. But he was able to come back and turn it around.

To return to a point near the introduction to this chapter, we make a great fuss about leadership these days But all too often we attribute leadership qualities to people we hardly know. Consider “young leaders”—to my mind an oxymoron. How can anyone be so designated before he or she has been tested in the crucible of experience? Who can know what flaws lurk below the surface? Indeed, this very designation can encourage hubris and thereby spoil what might have become real leadership. To repeat, leadership is a sacred trust earned from the respect of those people on the receiving end of it.

Assessing Managerial Effectiveness

You are a manager; you want to know how you are doing. Other people around you are even more intent on finding out how you are doing. There are lots of easy ways to assess this. Beware of all of them. The effectiveness of a manager can only be judged in context. This proposition sounds easy enough, until you take it apart, which I shall do in eight subpropositions.

For starters, (1) managers are not effective; matches are effective. There is no such thing as a good husband or a good wife, only a good couple. And so it is with managers and their units.

There may be people who fail in all managerial jobs, but there are none who can succeed in all of them. That is because a flaw that can be tolerable in one situation—indeed, be a positive quality—can prove fatal in another. It all depends on the match between the person and the context, at the time, for a time, so long as it lasts. As concluded in Chapter 4, the effective manager is the one, not with the good style, but with the necessary style.12 Thus, (2) there are no effective managers in general, which also means (3) there is no such thing as a professional manager—someone who can manage anything (see Watson 1994:220–221; Whitley 1989; Mintzberg 2004b).

Of course, managers and their units succeed and fail together. So (4) to assess managerial effectiveness, you also have to assess the effectiveness of the unit. The purpose of the manager is to ensure that the unit serves its basic purpose. As Andy Grove of Intel put it: “A manager’s output = the output of his organization + the output of neighboring organizations under his influence” (1983:40; see also Whitley 1989:214).

This is a necessary condition for assessing managerial effectiveness, but it is not a sufficient one. (5) A manager can be considered effective only to the extent that he or she has helped to make the unit more effective. Some units function well despite their managers, and others would function a lot worse if not for their managers. Beware of assuming that the manager is responsible for whatever succeeds or fails in the unit. History matters; culture matters; markets matter; weather matters. As for the manager, it is personal impact that matters, not unit or organizational performance per se.

This means that many of the numerical measures of performance (growth in sales, reductions in cost, etc.) tell us nothing directly about the manager’s effectiveness. How many managers have succeeded simply by maneuvering themselves into favorable jobs, making sure they did not mess up, and then taking credit for the success (Hales 2001)?

Even if a manager can be shown to have influenced the unit for better or for worse, (6) managerial effectiveness is always relative, not only to the situation inherited, but also in comparison with other possible people in that job (Braybrooke 1964:542). What if someone turned down for the job would have done a lot better, perhaps because it was an easy job to do? Of course you can drive yourself crazy asking such questions. Who would ever know? But if you want to assess managerial effectiveness—truly do so—then you can’t avoid this proposition any more than the others.

To further complete matters, (7) managerial effectiveness also has to be assessed for broader impact, beyond the unit and even the organization. What about the manager who makes the unit more effective at the expense of the broader organization? For example, the sales department sold great quantities of product, but manufacturing couldn’t keep up, and so the company went into turmoil. But can you blame the sales manager? After all, he or she was only doing the job. Isn’t general management responsible for these broader perspectives?

Viewed conventionally—which means bureaucratically—the answer is yes. In bureaucracies, all responsibilities are neatly apportioned. In the real world of managing, the partial answer is no. Organizations are flawed too; unexpected problems can arise anywhere and often have to be addressed wherever that is. No responsible manager can afford to put on blinders, doing the assigned job without looking left or right. A Charlie Zinkan or a Gord Irwin in the Canadian parks could not simply dismiss that fight between the developers and the environmentalists as the responsibility of the politicians. A healthy organization is not a collection of detached human resources who simply look after their own turf; it is a community of responsible human beings who care about the entire system and its long-term survival (Watson 1999:38).

But we cannot stop here. How about what is right for the organization being wrong for the world around it? Albert Speer was a brilliant manager, hugely effective in organizing armament production in Nazi Germany (Singer and Wooton 1976). After the war, the Allied forces put him in jail anyway. Speer might have been a lot more effective for the world, maybe also for the German people, had he been a lot less effective in organizing his unit—or, better still, if he had chosen to manage something else.

We make a great fuss about holding managers responsible and accountable, but give not nearly enough attention to asking, responsible for what, accountable to whom? Imploring managers to be “socially responsible” is fine so long as we take it beyond the easy rhetoric, into the difficult conflicts that such behavior has to address. (For an illustration, see the write-up of Alan Whelan’s day in the appendix.)

Some economists have an easy reply to this. Let each business look after its own business, and leave the social issues to government (Friedman 1962, 1970). This is a neat distinction that keeps economic theory clean; unfortunately, it has made a mess of society.

Is there an economist prepared to argue that social decisions have no economic consequences? Not likely: everything costs something. Well, then, can any economist argue that there are economic decisions that have no social consequences? And what happens when managers ignore them, beyond remaining within the limits of the law? The Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, living in the United States at the time, had an answer:

I have spent all my life under a communist regime, and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But a society with no other scale but the legal one is not quite worthy of man either. A society that is based on the letter of the law and never reaches any higher is taking very scarce advantage of the high level of human possibilities. The letter of the law is too cold and formal to have a beneficial effect on society. Whenever the tissue of life is woven of legalistic relations, there is an atmosphere of moral mediocrity, paralyzing man’s noblest impulses.13

Put together all these propositions, and you have to ask, How can anyone who needs to assess a manager possibly cope with all this? The answer here, too, is simple, in principle: use judgment. (8) Managerial effectiveness has to be judged and not just measured.

We can certainly get measures of effectiveness for some of these things, notably aspects of unit performance, at least in the short term. But how are we to measure the rest, and, in particular, where is the composite measure that answers the magic question? Watch someone like Fabienne Lavoie on the nursing ward for a few hours—or even, I suspect, a few months—and tell me how you are going to measure her effectiveness. Even in a hard-nosed business like banking, how will you measure the effectiveness of a John Cleghorn? Because the stock went up? (It did in those American banks that invested in the subprime mortgages.)

If you think that eight propositions to assess managerial effectiveness is a little excessive, not to mention academically detached, then think about the excessiveness and detachedness of the executive bonuses that ignored most of them. They relied on the simplest of measures, such as increases in the stock price in the relative short run. Executive impact has to be assessed in the long run, and we don’t know how to measure performance in the long run, at least as attributable to specific managers. So executive bonuses should be eliminated. Period.

Where Has All the Judgment Gone? Remember judgment? It’s what used to lie beyond measurement, in the darkness—a key to managing effectively.

And then along came measurement in its dazzling light. It was fine, so long as it informed judgment. Sure, measure what you can, but then be sure to judge the rest: don’t be mesmerized by measurement. Unfortunately, we so often are, causing us to drive out judgment.

In 1981, the Business Roundtable, a group of the chief executives of many of America’s most prestigious corporations issued their “Statement on Corporate Responsibility.”

Balancing the shareholder’s expectations of maximum return against other priorities is one of the fundamental problems confronting corporate management. The shareholder must receive a good return but the legitimate concerns of other constituencies (customers, employees, communities, suppliers and society at large) also must have the appropriate attention…. [Leading managers] believe that by giving enlightened consideration to balancing the legitimate claims of all its constituents, a corporation will best serve the interest of its shareholders. (quoted in Mintzberg, Simons, and Basu 2002:71; since removed from the Business Roundtable site)

In 1997, the Business Roundtable issued another statement, entitled “Statement of Corporate Governance.” This claimed that the paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporations’ stockholders. It explained:

The notion that the board must somehow balance the interests of stockholders against the interests of other stakeholders fundamentally misconstrues the role of directors. It is, moreover, an unworkable notion because it would leave the board with no criteria for resolving conflicts between the interest of stockholders and of other stakeholders or among different groups of stakeholders. (www.businessroundtable.org)

No criteria indeed—besides judgment. Some time between 1981 and 1997, by their own account, this collection of America’s most prominent corporate chief executives lost their capacity for judgment. If you want to understand what underlies the current economic crisis in America, which is really a crisis of management, here you have it, in a nutshell. (See “How Productivity Killed American Enterprise” on www.mintzberg.org.)

The message of this nonsense is that to be effective in any managerial position, there is a need for thoughtfulness—not dogma, not greed risen to some high art, not fashionable technique, not me-too strategies, not all that “leadership” hype, just plain old judgment. Some things are easier to measure than others, yet all but the simplest things have to get beyond the numbers.

Let’s take an example right here. I write books and develop programs for managers. People sometimes ask me for measures of performance of the latter, at the limit: “How much will our share price rise if Joanne goes on your program?” I reply in terms of the former.

“Consider a book you read recently: can you quantify its costs?” Sure: so much money to purchase it, so many hours to read it. “Good. Now, please quantify the benefits. If you can do that—measure its impact on you—please let me know and I will do the same for the program.” As a reader, you might be finding this book wonderful—4.9 on some 5-point scale or other—and never do anything with it. Or you may have hated every word—2.3 (some time to find this out)—yet use an idea from it a year from now without remembering its source.

Should people stop reading books because they can’t measure their impact? Should they stop managing companies because they can never be sure of their long-term impact? Bear in mind that reading a book is a simple matter compared with practicing management. Stop reading books if you like, but you will not be able to get rid of management. The absence of reliable measures can certainly open the door to all sorts of games—such as phony excuses about why a manager failed, or claims of success in the light of failure—but pretending that measures are more reliable than they are can open the door to a worse set of games. And so let’s bring back judgment, alongside measurement.

Developing Managers Effectively

So how should managers be developed? In 1996, we set out to rethink the world of management education and development, and as a consequence change how management is practiced—toward what is described in this book. We began in our own place, with “management” education in the business school. Some of us at McGill University in Montreal had serious reservations about MBA programs.

The conventional MBA is just that: it is about business administration. It does a fine job of teaching the business functions, but little to enhance the practice of managing. Indeed, by giving the impression that the students have learned management and are prepared for leadership, it encourages hubris. Moreover, it relies on learning from other people’s experience, whether more directly in the discussion of cases, or less directly in the presentation of theory—the distillation of experience through research.

We teamed up with the colleagues from around the world14 to create the International Master’s in Practicing Management (www.impm.org). This set the groundwork for a series of initiatives that followed. Four are discussed briefly in the accompanying box, after laying out the premises that lie behind them. All of this can be thought of as natural development.

1. Managers, let alone leaders, cannot be created in a classroom. If management is a practice, then it cannot be taught as a science or a profession. In fact, it cannot be taught at all.15 MBA and other programs that claim to do so too often promote hubris instead, with destructive consequences. Some of the best managers/leaders have never spent a day in such a classroom, while no shortage of the worst sat there obediently for two years.16

2. Managing is learned on the job, enhanced by a variety of experiences and challenges. No one gets to practice surgery or accounting without prior training in a classroom. In management, it has to be the opposite. As we have seen, the job is too nuanced, too intricate, too dynamic to be learned prior to practice. So the logical starting point is to ensure that managers get the best experience possible. As both Hill (2003:228) and McCall (1988) have pointed out, the first managerial assignment can be key, because that is when managers “are perhaps most open to experiences and learning the basics” (Hill, p. 288). Beyond that, the learning can be enhanced by a variety of challenging assignments17 (McCall 1988; McCall et al. 1988), supported by mentors and peers (Hill, p. 227).

3. Development programs come in to help managers make meaning of their experience, by reflecting on it personally and with their colleagues. The classroom is a wonderful place to enhance the comprehensions and competencies of people who are already practicing management, especially when it draws on their own natural experience.

It has been said of bacon and eggs that while the chicken is involved, the pig is committed. Management development has to be about commitment: to the job, the people, and the purpose, to be sure, but also to the organization, and beyond that, in a responsible way, to related communities in society.

As noted earlier, management development is about getting the meaning of experience, and that means busy managers have to slow down, step back, and reflect thoughtfully on their own experience. Accordingly, development should take place as managers go back and forth between the activities of their work and the reflections of a quieter place. This can be away at a formal program, or just getting away at work itself (e.g., an uninterrupted lunchtime). Either way, we have found that the key to this is small groups of managers sitting together at round tables and sharing experiences.

4. Intrinsic to this development should be the carrying of the learning back to the workplace, for impact on the organization. A major problem with management development is that it usually happens in isolation. The manager is developed, perhaps even changed, only to return to an unchanged workplace. Management development should also be about organization development: teams of managers should be expected to drive change in their organization.

5. All of this needs to be organized according to the nature of managing itself—for example, in terms of the managerial mindsets. Most management education and much management development is organized around the business functions. This is fine for learning about business, but marketing + finance + accounting, etc., does not = management. Moreover, a focus on the business functions amounts to a focus on analysis. This is certainly an important mindset for managers, but only as one among others. Being the easiest one to teach should not make it the main one to learn. We have more than enough calculating managers already. We need ones who can deal with the calculated chaos of managing—its art and craft—which highlights the importance of reflection, worldliness, collaboration, and action.

All of this has been carried into a family of programs that we developed, described in the accompanying box. Linda Hill comments near the end of her book:

This research suggests that new managers should see themselves as engaged in strenuous self-development. Their task is to learn how to capitalize on their on-the-job learning. This requires a commitment to continual learning, self-diagnosis, and self-management. The transition is daunting at best, and most organizations offer little support. (2003:234)

Development: From Management to Organization to Society to Self

In the mid-1990s, we begin to rethink the whole question of management education, which led to a family of new programs, four of which are described here.

IMPM: Adding Management Development to Management Education We began in 1996 with the International Masters in Practicing Management (www.impm.org), designed to shift business education to management education, and combine it with management development. The IMPM was created to help managers do a better job in their own organization, not get a better job in another one.

The MBA is taught in terms of the business functions, such as marketing, finance, and human resource management. The IMPM has instead been built around the managerial mindsets, one module on each of reflection, analysis, worldliness, collaboration, and action, spread over sixteen months. These are held in England, Canada, India, Japan and Korea, and France. Practicing managers, sent by their organizations, preferably in teams, go back and forth between these modules and their work.

Sitting in small groups at round tables, the managers learn from each other through the sharing of reflections on their experience. Sometimes they engage in “competency sharing”—sharing experiences on how they practice certain competencies (such as networking, or reflecting in a busy job), to raise consciousness about their practice. They also do “managerial exchanges,” pairing up to spend several days at each other’s workplace, to enhance their worldliness.18

ALP: Combining Organization Development with Managerial Development So-called Advanced Management Programs are often just short replicas of the conventional MBA: they use many of the same cases and much of the same theory, they are organized in terms of the business functions, and they seat managers in the same linear rows.

Our Advanced Leadership Program (www.alp-impm.com) has carried our learning from the IMPM further. Here companies contract for tables instead of chairs; they send teams of six managers, each team charged with addressing a key issue in its company. In three modules of one week each, spread over six months, the teams work on one another’s issues in a process we call “friendly consulting,” designed for impact back home. Our experience is that managers get into this deeply, as consultants no less than as team members, to drive significant changes in their companies.

IMHL: Adding in Social Development Our third program, the International Master’s for Health Leadership (www.mcgill.ca/imhl), has been modeled after the IMPM, but for practicing managers, most with clinical backgrounds, from all aspects of health care and around the world.