The Managerial Communication Process

Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- describe the levels of managerial communication;

- explain the main components of the communication process model;

- discuss barriers to communication in the communication process;

- identify ways to improve the communicative process.

Introduction

Managers have very different ways of communicating with coworkers, subordinates, and superiors. Effective managers can be abrupt, kind, or even forceful with others when needed. Managers communicate on different levels inside and outside the organizations, as well throughout the global economy. It is impossible to plan, organize, lead, or control business resources without effective communication skills.

Communication competency includes the ability to decipher and respond to what others are saying, and to understand why they communicate in the way they do, whether expressed directly or indirectly, and verbally or nonverbally. The communication process takes place on five levels: intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, organizational, and intercultural. These levels are frequently not mutually exclusive in a given communication situation.

Levels of Managerial Communication

Imagine you just scored two free tickets to your favorite basketball team on Monday. If you do not use the tickets, there is no refund available. Thus, your unused tickets will go to waste. What will you do? Deciding by yourself whether to attend the game, pass the tickets along to someone else, or let the tickets go to waste is an example of intrapersonal communication. Texting your best friend to determine his or her willingness to accompany you to the game is an example of interpersonal communication. Sending a text message to six of your close friends, telling them that the tickets are available, and that the first two to reply will receive the tickets is group communication. Offering your tickets to a business client who will be visiting from China on game day is an example of intercultural communication. In fact, if your first language is English and you practice a few sentences of Mandarin to use in offering the client the tickets, you are using several levels of communication. If your tone, quality, and pronunciation in Mandarin are exact, the gesture might payoff with your client in the future. Let us examine each level of communication in more detail.

Intrapersonal Communication

Intrapersonal communication is communicating within yourself. Intrapersonal communication involves the processes that occur inside an individual’s brain. When you interpret ideas to clarify the meaning of what you see and hear, you are engaging in intrapersonal communication. Intrapersonal means that you ascribe meaning to the symbols and cues that exist in your environment. We are constantly engaging in intrapersonal communication with ourselves in our minds and thoughts.

Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication requires interaction between you and another person. A dyad exists—two people communicating. During interpersonal communication you share a message with someone else. If both communicators share the same meaning, the message achieves its purpose and is understood. The intention and interpretation of a message must be correctly understood in order to be successful. Each person creates meaning in an exchange process, and they may or may not ascribe the same meaning to the message. Interpersonal communication elevates the message exchange and adds complexity; it also introduces the possibility that information can be misinterpreted or not be received at all.

Group Communication

Group communication involves three or more people in the process. Managers engage in this type of communication when they have meetings. Groups are generally small so that everyone can participate in discussions. Nonverbal and cultural issues can plague group communication. Consideration of the organizational climate is essential when there are international or host countries involved in the communication and decision making.

Generally groups learn to adapt, use structural intervention, and avoid the need for excessive managerial intervention, or they will part ways. Adaptation can be a problem. Adaptation happens when team members on both sides identify and acknowledge the differences they share and find ways to strategically work around them. Subdivision of the team’s tasks happens with structural intervention, so that the tasks are separated according to discipline. With managerial intervention, the team can become overly dependent on the manager. When the members part ways, generally it is a loss for all sides. It is not easy to adjust to group situations, but with the correct attitude, strong solutions are possible.

Organizational Communication

An organization is a social group of people who have different strengths but common goals. To achieve these goals, they interact through the organization’s communication processes and develop successful patterns and practices. Effective organizational communication requires knowledge of the structure. Many organizations, for instance, are virtual, multicultural, and multilingual. Technology is also changing how organizations communicate. To communicate effectively, you need to have knowledge about the channels through which the organization communicates. You must also be sensitive to the organization’s leadership styles.

Intercultural Communication

Intercultural communication requires knowledge and understanding of culture. Managers who engage in effective intercultural communication must understand the norms and standards of the country, organizational norms, and the values and beliefs of the people within the culture. Intercultural communication also involves understanding of symbolic meanings that different cultures ascribe to nonverbal behaviors people exhibit in their social interactions.

Many challenges exist for international work teams. Team members from one cultural group may use direct communication, while others prefer indirect communication. U.S. citizens tend to be direct; however, Japanese are generally very indirect. Those from indirect cultures do not like to say no or make others lose face. Accents and fluency can be a problem, even if everyone is speaking English. Who does not have a story about calling a U.S. company’s customer service phone number and speaking to someone in India, Pakistan, or Indonesia? Also, attitudes toward hierarchy and authority are different around the world. Mexicans view their boss very paternalistically; while in the United States, workers look at their boss as a businessperson. Conflicting norms for decision making can also cause problems. While U.S. business people want to make decisions very quickly, the Koreans often want to revisit and discuss items for longer periods of time before making decisions. This may mean that they revisit issues the Americans think have already been decided.

Cultural differences often result in a bias that one’s own culture is superior to any other culture: ethnocentrism. Communicators can sometimes have stereotypes about each other. Stereotypes may include overgeneralizations about the other person’s interpretation of time, personal space requirements, body language, and translation limitations. One learns about culture over time, and language transmits culture. Language controls thought processes; and therefore, the variations of thought processes between cultures. Some are deductive in their reasoning processes and others are inductive. Recognizing that people from other cultures may have different thought patterns is important when communicating and negotiating. Because we know our own culture very well, we do not have to think about it; however, when communicating with someone from another culture, we need to think about the similarities and differences that exist between us.

While the numerous cultures in the United States can cause communication challenges, the issue is now exacerbated even further by people who perceive themselves as members of an oppressed culture under constant attack by an oppressor culture. Oppression politics, also known as identity politics, has caused major rifts among the numerous cultures within the United States. These conflicts disrupt harmony and thwart goodwill among cultures separated by ethnic, racial, and gender differences.

Those who live within a minority culture might share an overriding set of customs that provide standards for behavior. If you unknowingly break a cultural rule, you could destroy a business relationship, see 50 percent of your advertisers flee, get sued, or be labeled racist, sexist, xenophobe, or homophobe. Your career can be destroyed by accusation alone, if the media puts you on trial in the court of public opinion for violating boundary limits of one of the subcultures existing within the American culture. Such snafus could be either verbal or nonverbal. Nonverbals include gestures, body language, facial expressions, dress, hairstyles, tattoos, and other outward signs that make verbals more or less believable. Some cultural norms that appear shocking to some may appear perfectly as normal, expected behaviors to others, as can be seen in the Window into Practical Reality 2.1.

Window into Practical Reality 2.1

Is Cultural Appropriation a Real Thing?

People commonly referred to online as “social justice warriors or SJWs” soldier the issues of their identity politics by direct confrontation with people from the oppressor class whom they perceive to have violated the boundary limits of their oppressed people’s culture. When SJWs believe that a member of the oppressor class has taken something of value from the oppressed peoples’ culture, they believe that cultural appropriation has occurred. SJWs tend to act in ways to reify their social construction of reality. They feel justified in confronting others, or attacking in some cases, irrespective of how shocking their behavior appears to objective third-party observers.

Cultural appropriation is perceived to be a real thing, which makes it hard for people to coexist peacefully in the larger American culture, especially when SJWs identify more as members of an oppressed culture (i.e., black and brown people as oppressed versus white people as oppressor) rather than all coexisting together in harmony as proud citizens of the United States of America. The ideology of political identity supersedes national pride because the politics seemingly become the identity of the person. Therefore, saying the pledge of allegiance, singing along with the national anthem, or saluting the American flag are taboo because these sacred words and actions belong to the oppressor class. Proselytes of identity politics have little interest in adhering to the unifying elements of the American culture. They perceive themselves as moral crusaders when they identify with a seemingly oppressed group (i.e., multimillionaire professional football athletes feel completely justified in taking a knee during the playing of the national anthem).

One distressing example of an SJW enforcing the boundary limits of cultural appropriation comes from an incident at San Francisco State University, which happened in 2016, where two people of color confronted a white student with accusations that he had appropriated the hair style of Egyptian or black culture. Bonita Tindle (a black female student) and her friend (a black male student) appeared to detain a white male student when they perceived the dreadlock hairstyle he was wearing was too close to dreadlocks often wore by people of African or Egyptian descent.

The white student asked, “You’re saying that I can’t have a hairstyle because of your culture? Why?”

Tindle responded: “Because it’s my culture. Do you know what locks mean?”

The encounter became physical when the white male student attempted to leave the encounter but was blocked from leaving, grabbed by his arm, spun around, and pulled forward by Ms. Tindle so that she could continue her rebuke of the young man for his crime of cultural appropriation.

The 46-second YouTube video of the encounter published on March 28, 2016, by Nicholas Silvera went viral and sparked debate among many. It caught the attention of Mark Dice, a video blogger known for his sardonic ridicule of what he refers to as “liberals” or as people on the far left. During the final few seconds of the video, Ms. Tindle asked the camera man, “Why you filming this?!” The camera man replied, “For everyone’s safety!”

Did Ms. Tindle have a right to detain and reprimand the white male student for his choice of hairstyle? What does this encounter tell us about the divergent world views in American culture? Why did Ms. Tindle see this as inappropriate rather than as an affirmation of her culture?

Source: www.youtube.com/watch?v=jDlQ4H0Kdg8.

Your managerial success is largely determined by your mastery of seven nonverbal elements (1) chronemics, (2) proxemics, (3) oculesics, (4) olfactics, (5) haptics, (6) facial expressions, and (7) chromatics.

How you view punctuality, the distance you stand from another person when in conversation, the clothes you wear, your jewelry, and even your word choice can become a barrier to effective managerial communication (MC). Nonverbal barriers are anything other than words that distract the recipient or lead to distortions that interfere with the reception of your intended message. Nonverbal differences happen across many dimensions of culture including language, gender, and generational divides. Basically, you have to learn about what you might encounter and not be afraid to ask questions when there is a nonverbal action that you do not understand. For example, in many Asian cultures personal silence in meetings is a signal that you need to call on individuals to get them to express their ideas. Culturally, nonverbals can have very different and often opposing meanings. As such it is best to avoid as many nonverbals as possible when communicating with someone from another culture, unless you are very comfortable in your knowledge of the culture.

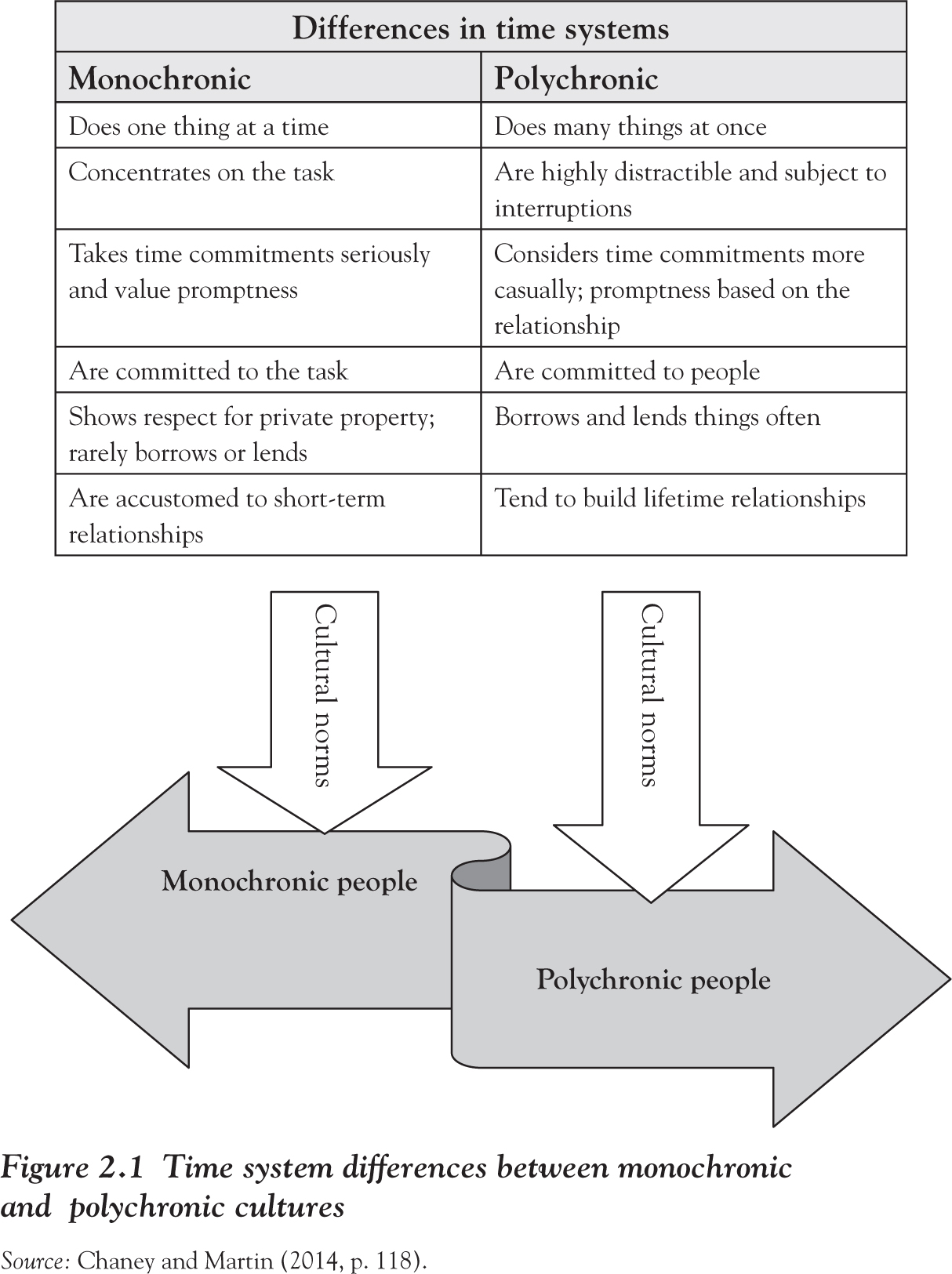

Chronemics involves attitudes toward time, which vary widely across cultures. Whether a culture is monochronic or polychronic can be very important to the success of a business deal. People from monochronic cultures take deadlines and meeting commitments seriously; they are punctual. People in polychronic cultures are not as punctual and do not take deadlines as seriously. Cultural norms shape perceptions of the importance of time, which differs between monochronic and polychronic cultures as seen in Figure 2.1. Some countries with monochronic cultures are the United States, England, Switzerland, and Germany. Some areas of the world with polychronic cultures are Latin America, Southern Europe, and the Middle East.

Differences in the concept of time may cause problems when trying to schedule online meetings, as someone from a monochronic culture will typically be online early or on time, while those from polychronic cultures may be engaged in something else that they feel is important and not join the online discussion on time. These cultural norms are neither correct nor wrong; they are merely noncongruent for team participants.

Proxemics, or the use of space, is another area of cultural difference. You might see differences in meeting room seating arrangements depending upon the proxemics of a culture. People in the United States have an intimate zone of less than 18 in for people they know very well, a casual-personal zone is 18 in to 4 ft, a social zone of 4 to 12 ft used with people with whom they work closely, and a public distance of over 12 ft for those they do not know (Hall, 1966). Cultural standards create different proxemics—some engage in hugging and kisses on the cheek or air kisses. In the United States a private office is considered a status symbol, whereas in Japan there are only a few, and even those are not used a great deal of the time. In France, the boss sits in the middle of the work area, with subordinates in offices around him or her.

Oculesics, or eye contact, is important because some cultures show respect by looking away, while others by almost staring, with many degrees of difference in between. Unfortunately, unbroken staring can be misinterpreted as hostility, aggressiveness, or intrusiveness when the intended meaning was just to appear interested. Minimal eye contact may be misinterpreted as lack of interest, understanding, dishonesty, fear, or shyness when the intended meaning was to show respect or to avoid appearing intrusive. In some cultures, one shows respect to women by not looking them in the eye; even though a man would normally have direct eye contact with another male.

Olfactics, or smell, can significantly affect communications. Smell impresses itself very strongly on our memories and remains long after the person has gone. Hygiene, perfumes, and what one eats are the main sources of personal smell. In business situations, it is important to bath regularly, use breath fresheners, refrain from perfumes, and have an understanding that what you eat or drink is secreted through your skin which others can smell.

Haptics, or touch, is interpreted very differently around the world. Knowing the cultural norms and standards for how and where one may touch and whom one may touch is important. In many parts of the world, men greet each other with a hug of varying degrees of intimacy rather than a handshake or a bow. In some countries, touching the top of the head is inappropriate. While a slap on the back in the United States means that you have done a good job, in Japan it has the opposite meaning. It is important to consider and understand what the correct etiquette for touching is in the different cultures with whom you may come in contact. Senior clerics criticized President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran for hugging the mother of the deceased Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez at his funeral (Akbar 2013). Physical contact, considered a sin when touching an unrelated woman in the Islamic religion, is seen as empathetic in Venezuela where hugging is common. Cultures exist where it is not appropriate for a woman and man to even shake hands in public if nor related.

Facial expressions may not always be what they appear. For instance, laughing when embarrassed is not unusual for Asians. The degree of animation has a deep cultural basis, as do gestures and the amount of gesturing that goes on during a conversation. Until you know how someone from another culture understands a gesture, you should refrain from using it or explaining it.

Chromatics, or the use and interpretation of color, can also be important. For example, black is the color of mourning for many Europeans and Americans, while white is normally worn for funerals in Japan, and red has funeral connotations in African countries. Purple is associated with royalty in many countries, but with death in some Latin American countries. Colors are particularly important when exporting products for sale in other countries and in selecting gifts for business associates.

The Managerial Communication Model

All the levels of MC impact the MC process model. Figure 2.2 illustrates nine components of this model. The model depicts two layers: the macroenvironment and microenvironment. The macroenvironment has an indirect influence on the communication and includes (1) organizational culture and (2) situational context. The microenvironment has a direct influence on the communication and includes (3) information source, (4) encoding, (5) message over channel, (6) decoding, (7) destination, (8) barriers, and (9) feedback.

The first process model evolved from engineering practices from the past. Claude E. Shannon, an engineer for the Bell Telephone Company, introduced one of the most influential early models of the communication process to study issues of interdepartmental workflow (Weaver 1949). Later Shannon and Weaver (1949) added a corrective element to the model called feedback. This feature makes this model an interpersonal process. The model has been changed over the years to reflect current research and practice.

The MC model has been very helpful in advancing communication theories in organizational, corporate, business, and managerial communication.

Organizational Culture

Culture consists of shared values, symbols, meanings, practices, customs and traditions, history, tacit understandings, habits, norms, expectations, common meanings, rites, and shared assumptions. Just as countries and regions of the world have their own cultures, so does each organization. Organizational culture includes the behaviors developed through rules, regulations, and procedures that promote the attainment of the goal. People within an organization share organizational culture just as ethnic groups share ethnic culture. Organizational culture determines how to do things through common agreement. The way workers interact socially at work assists in defining organizational culture. Communication helps to disseminate cultural expectations and bind the organizational culture together.

Coordinating and directing employees involves trade-offs. The difficult part for the management is to get all the workers in an organization to view the direction or goals of the firm in the same way. This is why it is not unusual for there to be subcultures within an organization. If the subcultures get prominent, effective communication is jeopardized. If subcultures diverge from the mission of the firm, they can actually be harmful to the organization. Generally, however, goals help individuals to learn their position within the organization and the firm’s expectations. Managers must realize, however, that workers’ perceptions of information, their thought patterns, and their values may be very different from the managers’ perceptions. When an individual’s values match those of the organization, job satisfaction increases.

Managers of international organizations must consider the cultural differences among the countries that are working together. This includes understanding differences in the laws, culture, and working climate of the countries involved. When group norms are different, it is not always easy for people to adapt to one another. However, if the groups can be taught to recognize and appreciate these differences, it is easier for them to understand and work together. Language also plays a major role in developing our mindset and how we think. When someone is speaking a second language, they are often in the mindset of their first language. Therefore, people may not interpret messages in the way they were intended by the sender. In fact, there may not at times be equivalent words to express some thoughts or ideas between the two languages.

In order to manage an organizational culture, top management must have a strategic plan, develop cultural leaders, share the culture by communicating effectively with staff, measure performance, communicate culture to employees, and motivate them. Doing this requires trade-offs between the members of the organization at all levels. In order to accomplish the mission of the organization, some people will typically strive to gain power, while expecting others to surrender some of their flexibility and independence. When working within the corporate culture, you will need to remember that you are working with social elements that may or may not seem rational.

Continuing dialog will help all of us understand each other, but mistakes will happen. The larger the organization, the more opportunities there are for miscommunications due to cultural differences. Along with continuing dialog, we must also consider the particular situation in which the communication is happening.

Situational Context

The situational context is another component of the macroenvironment of the MC process. Is the situation critical, meaning is it dangerous or imminent, or does it involve planning for the future? The situational context will often determine to whom the communication is made and what channel is chosen to achieve the communication. Situational factors include gender, age, cultural differences, as well as whether the relationship is with a subordinate, peer, or superior.

We will now continue our discussion with the seven components of the microenvironment involved in the MC process.

Information Source

An information source is the person from whom the communication originates. When you call on a customer or an employee and give them a message, you are the information source. The message is the information you want the receiver to act upon. In creating a message, you encode it.

Encoding

When you create meaning which will be sent to a targeted recipient, you are encoding the message. When doing this, you must consider many things about the person or persons receiving the message. The more you know about your audience, the easier it is to communicate with them because you have an idea of how they will respond to what you say. Audience characteristics include age, economic level, educational background, and culture.

Channel

A channel is the medium through which the message travels. E-mail, memorandum, letter, text, telephone, social media, fax, face-to-face, meeting, and company newspaper are examples of channels. Channel selection can be determined by how soon the recipients need the information, confidentiality of the information, the hierarchical relationship of the communicators, the location, gender, culture, and level of education of the recipient.

Decoding

The person receiving the communication has to decode the message just as the information source encoded it. However, we all have different screens through which we filter messages. When you decode, you interpret and translate the message you have received according to your mindset. The more alike we are, the more likely our message will be understood as it was intended to be. The more different we are, the more room there is for mistakes in decoding, both in interpreting and in translating the message incorrectly.

Destination

The person or people receiving and interpreting the message are the destination. The recipient can be a person or a group receiving a message that you send. The recipient, or destination, of a message can be intended or unintended. No matter how hard you work to make it perfect, there will be some distortion in the message.

Barriers

Barriers are a given in any form of communication. Barriers are items that interfere with the message. Barriers include physical or psychological problems, language, gender issues, education-level issues, generational issues, and nonverbal differences.

Physical and psychological barriers can distort the message. Physical and psychological barriers may include disabilities, health problems, parental issues, elder-care issues, money problems, or mental issues. Any of these barriers can impact a person’s work. How a manager handles the physical and psychological problems of subordinates is important. The ability to handle subordinates’ issues is influenced by the manager’s knowledge of the situation and the personalities of those involved. Given that people are going to experience some difficulties during their lives, it is generally better for the manager to exhibit compassion and try to find a solution to problems rather than to put more pressure on employees for things beyond their control.

Language barriers happen even if both sides speak the same language. There are dozens of different dialects of English spoken as a first language across the world. Many others are taught variations of those dialects of English because English is the number one language used in business around the world. However, just because two people are speaking English, it does not mean that they understand each other. The spelling, definition, and pronunciation of words can all be different. English is not the only language in which this happens, so if you learn another language you must realize that there are variations in the languages used throughout the world. Translation from one language to another adds additional challenges, as it is not always possible to translate idiomatic expressions from one language to another.

Gender barriers arise even among those within the same culture. Problems are magnified by the fact that expectations for behavior and interaction vary widely with gender. The gender barriers range from the recognition of complete equality between the genders to very strict rules that separate the genders. In China and Japan, for instance, women speak in a different tone than men when expressing the same point of view. In orthodox Islamic areas of the world, girls and boys do not attend school together, which means that girls do not have the same resources available or subjects to study as the boys have. In many cases, men and women are not allowed to work together in Islamic countries. Therefore, there are many communication strategies to be considered when communicating with an individual who is different both culturally and in gender.

Research has shown that the gender of the participants, the team’s overall gender composition, and the gender orientation of the task influences the feedback-seeking behavior among team members (Miller and Karakowsky 2005). Because they are more concerned about interpersonal relationships and generally more compassionate, women are more open to feedback than men (London, Larsen, and Thisted 1999). The type of position and whether it is a traditional or nontraditional one has a direct effect on the method women use to obtain feedback (Holder 1996). The requirements of the task may emphasize gender-differentiated skills that increase gender differences within the group. Studies have shown that men seek feedback more on male-oriented tasks within a male group, and females are less likely to seek feedback in a female group performing a male-oriented task. Women in mainly male groups and masculine-oriented tasks are more likely to seek feedback than are women in male groups with female-oriented tasks. When expertise is clearly present in both genders, both groups seek feedback; however, men tend to not seek feedback in situations that are not involved with masculine-oriented tasks. As more women enter the workforce, fewer and fewer positions are considered to be female- or male-specific jobs.

The educational levels between and among people can also be a communication barrier. You want to control your vocabulary and sentence structure when communicating with people below or above you both inside and outside the organization. The more you know about the people you are communicating with, the better you can choose words and sentence structure that will help them decode your messages correctly. A manager in a manufacturing plant where the workers typically have only a high school education would want to communicate at approximately an eighth-grade school level rather than at a college level. Most newspapers are written at a sixth- to eighth-grade school level. Did you know that you can check the grade level of your written messages while using Microsoft Word?

Generational differences are a large barrier to communication in organizations. As Table 2.1 illustrates, there are five generations of communicators in the workplace who impact the effectiveness of your success in the MC process. While historians and sociologists differ somewhat on the exact years that differentiate the generations, there is general agreement on the characteristics of each group. If you were born between 1925 and 1945, you are a traditionalist. If you were born between 1946 and 1965, you are a Boomer. If you were born between 1966 and 1979, you are a Gen Xer. If you were born between 1980 and 1999, you are a millennial. If you were born between 2000 and the present, you are a Gen Zer. Effective managers recognize generational issues and communication preferences that differentiate Traditionalists, Boomers, Gen Xers, Millennials, and Gen Zers.

Intergenerational issues are the communication gaps that exist because of age and behavior patterns among various groups of individuals. Each group has habits that are broadly defined by their life experiences. Boomers are more likely to use e-mail and voice messaging rather than texting or sending tweets, which Millennials routinely do. Traditionalists might not even use computers on a daily basis. Imagine the barrier this habit alone would create if a millennial is attempting to tweet a Traditionalist who probably does not even have a Twitter account.

The oldest generation cohort likely to be in the workplace are Traditionalists, born between 1925 and 1945. They are considered to be loyal, highly dedicated, and risk-averse employees (Jenkins 2008). They place a high emphasis on interpersonal communication, obey the rules, value a top–down management style, and rarely question authority (Kyles 2005). Therefore, Traditionalists will expect face-to-face communication with their boss, will probably not carry a smartphone, and may only be involved with e-mail and Facebook because of their grandchildren.

Baby Boomers were born between 1946 and 1965. Boomers tend to be workaholics. Most have had to learn technology in the workplace but still appreciate face-to-face conversations. They use smartphone, e-mail, and text messaging, and many also use social media.

Gen Xers were born between 1966 and 1979 and represent the smallest generational cohort in numbers. Many were born into homes with two working parents and are considered the latchkey generation. They are self-reliant and have carried this characteristic into the workplace (Macon and Artley 2009). Unlike their Boomer parents, Xers place more emphasis on a work–life balance, often choosing personal life over work. Xers are pragmatic, adaptable, entrepreneurial, skeptical, and distrustful of authority (Arnsparger 2008).

Millennials were born between 1980 and 1999. Technology, September 11, 2001, the Columbine School shooting, and the increasing ease of obtaining information via the Internet have helped to shape this generation. Some call them digital natives because they do not remember a time without technology. Millennials like structure, open communication, and direct access to senior management (Hershatter and Epstein 2010).

Gen Zers were born between 2000 and the present and represent the generation of young people who never knew the world without the Internet. Two in five Gen Zers are born to unmarried mothers. U.S. statistics from 2016 indicated that proportion to be 69.8 percent among blacks, 52.6 percent among Hispanics, and 28.5 percent among whites (Martin et al. 2018). As a result, many Gen Zers come from homes where a female is the head of household, and many do not have a connection with their biological fathers. Gen Zers are adept at social media and are used to having information speedily at their fingertips. This technology savvy generation share and retain constant communication via digital media (Desai and Lele 2017). Gen Zers’ identities can be directly connected to an online image of themselves; and they also can be influenced by ideological beliefs that they derived from their social network connections, not necessarily germane to a healthy connection with others. Table 2.1 gives some ideas on the views and ways to communicate effectively among the five generations.

When communicating the corporate strategy, organizations expect everyone in the firm to share a common view of where the organization is going. However, if all levels of communication are not addressed, this may not be possible. Given the generational differences that exist in most work environments, it is important for a manager to employ various strategies including intergenerational education, succession planning, mentoring, and technology education. Managers who take the time to develop a multigenerational communication strategy generally experience greater cohesion, trust, innovation, and collaboration across generations.

The downward flow of communication should be offered in multiple formats to ensure that everyone receives information in a timely manner. While Traditionalists and Boomers may prefer face-to-face verbal exchanges, Gen Xers, Millennials, and Gen Zers may prefer texting, e-mail, or corporate broadcasts. As the younger generations replace Traditionalists and Boomers, mentoring between the generations becomes very important. This means that mentors need to be educated about how to communicate successfully with the Gen Xers, Millennials, and Gen Zers; and mentees need to understand when face-to-face and verbal communication is preferable to the technology-assisted channels. Corporate education is a must for all generations as can be seen in Window into Practical Reality 2.2.

Window into Practical Reality 2.2

Generational Difference in Information Sharing and Retrieval

Millennials may use libraries, but only through the Internet—many have never set foot in a library building. While Traditionalists and Boomers will generally opt for the newspaper for business news, Gen Xers and Millennials will want to read the news as it happens on their electronic devices. Gen Zers force the issues by being directly involved in helping to shape news, not merely consuming it. They are more prone to engage in physical reactions to what they experience online as vital to themselves. Rather than disengaging from social networks that offend the user, they can take extreme actions. Some younger Gen Zers have gone so far as to attempt or actually commit irreversible actions (i.e., suicide because of cyberbullying). Unlike other generations, Gen Zers are passionately connected to their online worlds via Facebook Messenger and Twitter. Business Insider’s Maya Kosoff (2016) reports that “80% of teenagers they surveyed said they used Facebook Messenger as a primary or secondary form of communicating with friends.” A factor for all generations to consider is whether maintaining a history of the communication is required or advisable; with texting you do not have a way to save the communication for historical purposes, but you do with e-mail and other written forms of communication.

Generational issues present many problems for management including conflicts in the workplace that can result in reduced profitability, hiring challenges, increased turnover, and a decrease in morale between the generations (Macon and Artley 2009).

Managers with a multigenerational staff need to be aware of the different preferred modes of communication. The Millennials and Gen Zers are early adopters of new technology using texting first, phone second, e-mail third, and other mediums after that. While Generation Xers are computer savvy, they are not attached to their computers and handhelds in the way Millennials are. Boomers learned their computer knowledge on their own, on the job, and have less formal training in technology than their younger counterparts. Traditionalists have primarily learned enough about technology to communicate with their grandchildren. The ability to use computer-mediated communication (CMC) is one of the main differences between the generations. One of the main problems with CMC is that while it is quick, it is basically devoid of nonverbal communication. Some companies have instituted non-CMC days because people were using CMC to communicate with those sitting next to them. On technology-free days, people must get up and go see the person they need to communicate with if they are in the same building. Challenges can emerge when elitist attitudes develop among generational workers. Social Identity Theory recognizes that members of the various groups may see themselves as superior to other groups because of either their long-term knowledge of the company or their CMC knowledge.

Corporation memory is changing. Knowledge transfer methods are changing. Cross-generational teams offer the best avenue for moving organizations forward, though challenges exist in making them work effectively. Gen Xers, Millennials, and Gen Zers are more open to the informal nature of teamwork, whereas the Traditionalist and Boomers accustomed to working alone early in their careers have had to learn to work on teams. Millennials and Gen Zers also tend to get bored very easily which can cause increased turnover. As younger generational groups join the workforce, challenges for effective communication across generational divides will continue.

While there are many differences, there are also similarities between the generations. Those of all generations want to feel valued, empowered, and engaged at work. While the Gen Xers, Millennials, and Gen Zers are more vocal about flexibility, Boomers and Traditionalists also want some flexibility.

Feedback

When the destination receives your message and encodes a response, the process of feedback happens. While the destination may or may not give the feedback that is expected, the quality of the feedback will be determined by the level of barriers. If barriers are small, the destination will send correct or favorable feedback to the source. If barriers are large, the destination will send incorrect or unfavorable feedback. If a distorted message reaches the destination, the destination might not interpret the message properly and as such there will be no feedback or the feedback may not be applicable. However, you might construe no feedback at all an indication that the message was not received—or, if you are a bit paranoid, you might construe your message as being ignored. Never assume your destination has ignored your message. For e-mail and voice messages, give the recipient 24 hours to respond, and for old-fashioned USPS “snail” mail, give the recipient a week to respond. If possible, respond in kind in terms of the message channel. Return a call with a call, a text with a text, and e-mail with an e-mail. This assures that your channel selection will be correct, especially when the communication is with someone outside of your generational population.

Improving the Communicative Process

There are three main reasons why messages can fail in the communication process (1) framing effects, (2) illusion of control, and (3) discounting the future.

Framing effects occur when the decision is influenced by the way the problem or issue is phrased, thus helping or hurting any chance of selecting the preferred alternative. Choices can be presented in a way that highlights the positive or negative aspects of the same decision, leading to changes in their relative attractiveness. Negative framing predisposes the recipient to a negative opinion of the issue.

Illusion of control refers to scenarios in which managers believe they can control the outcome or influence events even though they may not have control. When managers argue that they can control or predict all the variables, they are usually delusional. Experienced managers might know they have succeeded in the past, but they also should be aware that past success is no guarantee of a future outcome. Believing an outcome is guaranteed and selling this notion to others is illusion of control. The illusion of control is exhibited when a manager argues, vehemently, that the competition “could never . . .” or “I doubt very seriously that . . .,” when there is no evidence other than emotional hunches.

Discounting the future occurs when managers use communication tactics that lead to a preference for short-term benefits at the expense of longer-term cost and benefits. Corporate leaders can fall victim to the pressures of making money for shareholders while distributing earning to owners. Nevertheless, pressure to impress can create a dangerous rhetoric that leads managers to value short-term profits over long-term competitive advantages for their business.

Use the MC model to dissect your own approach to business communication and scrutinize positive and negative examples of the communication of others. Learning to decipher and understand what others are saying and perhaps why they communicate the way they do, whether they say it directly or indirectly, can be important to you personally and to your company. The communication process model reflects the theories that underlie communication and breaks the process into elements that helps managers navigate the challenging communication process.

Summary

There are five levels of MC: intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, organizational, and intercultural. Intrapersonal communication involves the processes that occur inside an individual’s thoughts. Interpersonal communication involves another person with whom you interact. To manage effectively, recognize generational issues and communication preferences that differentiate Traditionalists, Boomers, Gen Xers, Millennials, and Gen Zers. Group communication involves three or more persons. Organizational communication requires knowledge of structural expectations. Intercultural communication requires knowledge of other cultures.

The nine components of the MC process model depict two layers: the macroenvironment including organizational culture and situational context; and the microenvironment including information source, encoding, message over channel, decoding, destination, barriers, and feedback. Communication barriers include physical or psychological issues, language barriers, gender issues, education-level issues, and generational issues.