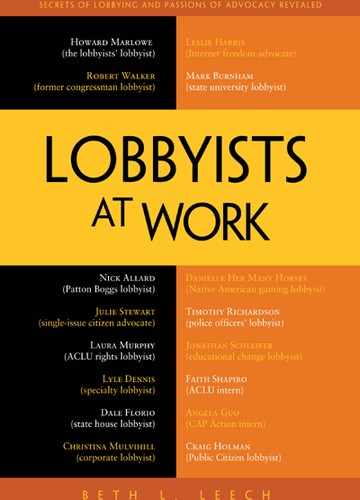

Timothy Richardson

Senior Legislative Liaison

Fraternal Order of Police

Timothy Richardsonis senior legislative liaison at the Washington office of the National Fraternal Order of Police, the largest organization of law enforcement officers in the world. The FOP serves as a union as well as an educational and advocacy resource for its more than 330,000 members. In 2011, the FOP reported spending $250,000 on lobbying; in the 2012 election cycle, it made $41,250 in campaign contributions—95 percent of them to Democrats.

Richardson has been with the FOP throughout his career, beginning as a legislative assistant in 1996 and being promoted to his current position in 2001. Both his father and his grandfather were police officers. He has a bachelor’s degree in English/ professional writing and political science from Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania.

Beth Leech: How did you begin your career? How did you end up working for the Fraternal Order of Police?

Timothy Richardson: Good timing. After graduating from college, I found a paid internship—which nowadays do not exist—working for the Senate Republican Policy Committee. It was the time of the federal government shutdown of 1995 and 1996, after President Clinton vetoed the budget the Republicans sent him. “Nonessential” government workers were on furlough for almost a month, so the committee was really squeezing every ounce out of their interns. We interns had more of an opportunity to be engaged in how the Senate and legislative process worked.

I worked for the committee for about six months, and it just happened that the FOP, which had selected a new executive director in 1995, had finally gotten money to hire another staff member.

Richardson: In Washington. I saw an advertisement about the job in the basement of the Russell Senate Office Building. My grandfather and dad were police officers. My dad at the time was chief of detectives and his most senior detective was the state lodge president of the Fraternal Order of Police. I had known that detective since I was two or three years old. He knew I was interested in the position, put in a good word for me, and my résumé made it to the top of the pile pretty quickly. They interviewed me in May and I started here in June 1996.

Leech: You have been at the FOP ever since?

Richardson: I have been here ever since. At the end of that first year, my boss had said, “What do you think? Do you like it?” I said I did. He was a good mentor and taught me a lot about advocacy, about lobbying. I told him, “I’m probably not going to stay past the next Congress, but I’m going to commit to staying the entire next year for sure.” That was in 1996.

Leech: What was the learning curve like? You knew a fair amount about police officers in general, having grown up with them, and your degree is in political science. How ready were you to be on the ground, in the real world?

Richardson: Most of the learning curve was about the approach. Because of my work in the Senate, I had a very good grasp of procedure and the basics of how a bill really becomes a law. As a staff member, I also watched advocates who were coming to the committee to say, “This is important. Here are the merits of this.” I had seen lobbyists advocate, and now that’s what I was being asked to do. That was the only really tough part of the curve.

Leech: What was hard about it?

Richardson: Learning how to approach a staffer, not as another member of the staff, but as someone who wants something. For my first three or four months at the FOP, I was in the boss’s pocket. He had a lot of experience, so I followed him from office to office and learned by doing and watching. He had been an assistant director at ATF [Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives] and he was in charge of their congressional relations for the last ten to fifteen years of his career. He was very savvy about how the policy process works and how best to be an advocate.

It didn’t take too long for me to figure things out. I was lucky again with the timing. Back in 1996, it was usual for Congress to take a break—unlike now where Congress goes to Christmas Eve or later every year. It was an election year, and Congress met the last time on September 30 and then not again until January. So I had three months to really learn the FOP’s issues in depth, learn where the organization had been historically, and find out how the organization worked. When the 105th Congress started in January 1997, I was prepared.

Leech: The FOP is involved in a lot of issues. I looked at your last lobbying disclosure filing and there were sixteen pages of issues the FOP has been lobbying on. How would you describe this range of issues?

Richardson: A lot of things changed after the attacks of September 2001. The FOP got involved in a whole new menu of issues specific to homeland security. The administration at the time believed that to fight terrorism, you not only needed to access the military, but also domestic law enforcement. Some acts of terror are not necessarily acts of war, but they are crimes that need to be investigated and prosecuted like any other crime.

Yes, we’ve got an awful lot of issues. There are sentencing issues: locking bad guys up—the longer the better—and identifying where different criminal activities fall in the sentencing guidelines. There are firearms issues, immigration issues, Internet issues—like the criminal acts covered under the Stop Online Piracy Act, retirement issues for our members, and even education issues like the Children of Fallen Heroes Scholarship Act.

The FOP is also a labor organization, but the Grand Lodge, which is the national governing body of the FOP, is not a union in and of itself. We represent unions. Our members are part of local bargaining units that sit down with city mayors and county executives and negotiate contracts. There is always a lot about the labor side of things that needs work.

Sometimes, yes, we find ourselves in the middle of a lot of issues that might seem unusual for police officers. We are very much involved in the online environment now. We were drawn into Internet spectrum issues connected with the National Public Safety Broadband Network, the aim of which is to provide nationwide emergency communications. I sat on the board of directors for the Public Spectrum Safety Trust as a representative of the FOP. We were involved in SOPA [Stop Online Piracy Act], which we supported because it involved curbing fraudulent and criminal activity online.

Leech: How deep does your knowledge need to be of all the various issues that you are involved in, in order to lobby on those issues effectively?

Richardson: For the Internet issues, for example, I did not need technical expertise but rather enough familiarity with the technology that I could make a rational argument. I needed to be able to explain it to a staff member or a member of Congress who didn’t have even basic knowledge about how these things worked.

At the same time, these technical issues are not top priorities for the FOP.

What we do often when we have those situations where we need some technical expertise is that we look internally and find someone who is an expert. We have two guys who I rely on quite a bit when it comes to the technological ins and outs of public safety radio spectrum management, how broadband works, that sort of thing. But I know enough. A lobbyist can make a formidable argument without knowing everything down to the last particle, but that lobbyist will be more effective with a working knowledge of the technicalities.

Fortunately, staff and members of Congress are often in the same boat. I will come across staffers, particularly on the relevant committees, who know this issue down to the bones and who could construct a broadband network if you gave them a toothpick and a piece of gum. Then I may meet with staffers who are not on the committee, who have never dealt with this before, and they may not know what “spectrum” means. When I am advocating, it’s a matter of knowing my audience as well as the issue.

Leech: These experts who you bring in, are they in your office in DC?

Richardson: One of the guys is retired from the Metropolitan Police Department here in DC. They called him out of retirement to do the secure communications for the inauguration. The other experts are drawn from our three hundred and thirty thousand members. We’ve got experts in just about anything. It’s just a matter of locating them, getting on the phone with them, or having them send me some bullet points about what I need to know.

Leech: How big is your office? How many people are doing full-time advocacy for the FOP in DC?

Richardson: We have the executive director, myself, and one other legislative liaison.

Leech: What are the top priorities for the Washington office?

Richardson: Priorities are set by the membership, although I make a distinction between what we call a “top legislative priority” set by the membership and legislative priorities dictated by which issues are moving on the Hill. The latter are things that can actually be achieved in the current political environment. While we have top priorities from the membership, those may not necessarily involve the majority of our staff’s time.

Leech: Because you have to react to what is actually happening in Washington?

Richardson: Correct. Some of our top priorities are very far-reaching and may not realistically be bills that we can achieve in the near future. We have a Social Security issue connected to getting rid of the Windfall Elimination Provision. Police officers usually do not pay into or receive Social Security, unless they work at some other job as well. The Windfall Elimination Provision eliminates up to fifty percent of Social Security for those officers who have worked outside jobs or who qualify for spousal or survivor Social Security benefits. We have been working on that issue since 1997. We also have a Collective Bargaining Bill that we almost got through in 2004 and 2007, but regrettably fell a little short. We could not reduce that shortfall in the last Congress and we are unlikely to do so in the 113th, considering the partisan makeup of the House.

Leech: This is because public safety employees currently don’t have a federally guaranteed right to collective bargain?

Richardson: The bill would establish a national floor of what public safety employees’ rights are. Those rights vary widely. There are states that have very solid public safety employee laws that govern their labor relations. Pennsylvania and Ohio settled that issue on the ballot. But, as we saw in Ohio and Wisconsin, those rights can also be taken away. We want to put a floor in place nationwide.

Leech: We’ve talked about a bunch of different issues that the FOP has been involved in. What sorts of steps does a lobbyist take to try to achieve policy goals like these?

Richardson: The most important thing is getting yourself on the radar screen. You first need to find a staff member who will listen to you. You want that staff member to work for a member of Congress who would be interested in your issue and who would want to help—who would want to be identified with your organization and with the policy objective that you espouse. There are a number of ways of picking that person. Obviously, whatever the issue is, you want to first look at the relevant committee and you want to try and get a member with seniority, if you can. Sometimes you may have district or state ties to the member that the organization can use.

That’s the first step and that’s often the most difficult. Staffers and members are inundated with policy ideas and with constituents sharing their views. It’s not magic, but the trick of it is to find the right person. Ideally, you will find a member of Congress who is interested in the issue and who has ties to the organization, either through constituents or because they want to be a champion for the organization. You’ve also got to make sure that it is an issue on which there is some agreement, or it won’t get very far in Congress.

Leech: The general public seems to think that this all happens because of campaign contributions. What role do you think campaign contributions play?

Richardson: I think for the most part that it’s just one other way to try to capture that member’s attention. I don’t think it’s any more or less effective than any other strategy. The FOP established its national PAC in 2004.

Leech: Relatively recently.

Richardson: Yes, and having a PAC really hasn’t made any difference in how we approach things day to day. It might make a difference for other industries, but obviously there aren’t any pro-crime members of Congress, although there are a few who are anti-law enforcement. In general, law enforcement officers are popular. Publically elected officials want to support police officers and help them do their jobs. That was one of the things that attracted me to the FOP. I liked serving on congressional staff and wasn’t sure that I wanted to represent a “special interest.” But law enforcement officers are out there protecting everybody, whether you make a political contribution or not. That is a really special interest.

The chief role of campaign contributions is to get that member’s attention, but regardless of the check that you write, unless that individual member of Congress wants to work with you on issues, you are really wasting your money. Thus, we are very selective about who we do give to.

Leech: You were talking about the first step in approaching an issue as a lobbyist, and you had gotten to the first step, which is getting a member of Congress on board with you.

Richardson: Right. Let me give you an example. We had a staff member whose husband is a federal officer while she was an employee here. In the Commonwealth of Virginia, they were working on legislation called National Blue Alert, similar to an Amber Alert but only used when an officer is killed in line of duty or severely injured. It worked the same way as an Amber Alert but it relies on the description of the suspect or the vehicle that the suspect used. An alert would go out and light up along highways: “Watch for a red Chevy with a six-foot-two man with a ski mask and a sawed-off shotgun,” or whatever the description was, so that the public could alert police.

We crafted some legislation that would make the National Blue Alert a national plan. We have an excellent working relationship with Representative Steny Hoyer, who was majority leader for the House. We took the legislation to him. He put it into bill language, and then Representative Michael McMahon from New York introduced the bill with Mr. Hoyer’s support. The plan did not cost any money because it was calling on the resources already in place from the Amber Alert. It was a positive for law enforcement. You had the Fraternal Order of Police, the oldest and largest organization of police officers in the country, saying that this was a good thing, that this was important to us, so the issue started rolling very quickly. This was in 2010, and unfortunately, it was very near to the end of the congressional session, so there was not an opportunity to vote on the legislation.

Leech: Because there is limited space on the legislative calendar, right?

Richardson: Very much so, which is why having someone like Mr. Hoyer on your team is so important. When we got to the 112th Congress at the beginning of 2011, McMahon had been defeated by a freshman Republican, Michael Grimm. Grimm immediately reintroduced the bill without talking to the supporters and then it became somewhat political. Eventually, we were able to sort everything out and get everybody on the same page and that legislation passed the House during National Police Week. Unfortunately, in the Senate we faced Senator Tom Coburn, who has blocked just about everything we have tried to do in the last two years.

Leech: Any idea why that is?

Richardson: He is very much against law enforcement as a federal concern, and does not believe the federal government should be involved in public safety laws.

Leech: Is that one of the reasons the FOP ends up having more allies within the Democratic Party than the Republican Party? I noticed that most of your campaign contributions do go to Democrats.

Richardson: It depends. When it comes to a lot of the labor issues, we find ready allies on the Democratic side. When it comes to criminal justice to fund crime measures, we find a lot of allies on the Republican side. It really depends on the issue. Dr. Coburn is a unique case. He just blocks us across the board.

Leech: So the Blue Alert has not become law. Do you have any other examples of issues you have worked on?

Richardson: Yes, we also have legislation that I have been working on since my first day or two in here. It’s a bill to allow law enforcement officers, active and retired, to carry concealed firearms even when they leave their jurisdiction. This issue crops up frequently in law enforcement because, unlike other nations that have national police forces, in the United States they are broken down into local jurisdictions. There are eighteen thousand different jurisdictions in the United States, although a lot of them overlap. You’ve got federal, local, and state overlapping jurisdictions. Every chief is a king and every sheriff is a duke, so everybody does things a little differently. Police officers needed the right to carry their firearms when they entered those other jurisdictions.

We passed that as a law in 2004: the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act. But, of course, you never get everything right the first time. What we discovered after we passed the law is that civilian law enforcement officers working for the Department of Defense did not have a statutory arrest authority—so under the definition of “qualified law enforcement officer” that we built into the bill, they still did not have the right to carry their firearms outside of their jurisdiction. The officers working for Department of Defense could apprehend suspects but they could not arrest anyone, so the law’s language excluded them.

We were stuck with that. So we rewrote some language and passed an amendment in 2010 that just said every police officer, as defined by the federal government, who works for the executive branch is covered.

Leech: Problem solved.

Richardson: Well, no, actually. It turns out that the amendment helped the Amtrak officers and some other federal officers, but it still did not cover the Department of Defense officers. What we had to do was go back into the law and add the word “apprehension” and cite the Uniform Code of Military Justice, because that’s where the apprehension authority for the Department of Defense law enforcement officers apparently derives.

This was back in the 111th Congress, later in 2010. We got agreed-upon language. We cleared it with the Senate Armed Services Committee and we had it inserted as part of the National Defense Authorization Act at the close of the last congressional session. We had support from Senator Carl Levin, the Armed Services chairman, and from Senator John McCain, the ranking Republican member of that committee. All t’s were crossed, the i’s were dotted, and then the amendment was stripped out.

I later found out that the amendment was dropped because somebody in the House Judiciary Committee had seen it and said, “Wait, we don’t know what this does. We don’t know what this is all about. It’s got to go.” It actually did fall into their jurisdiction. It wasn’t just an Armed Services issue.

We had to come back the next year, in the 112th Congress and redo all that. Right away we were meeting with members of the House Judiciary Committee to go over the same ground we had gone over with the Armed Services committee members, and we finally got the language inserted. Senator Jim Webb was a huge help to us, as was Senator Leahy. Patrick Leahy is one of our most stalwart and steadfast champions on the Hill. He does a lot for our law enforcement officers and we were able to get the amendment inserted into the bill. The House Judiciary indicated that they did support the inclusion of that provision, so Armed Services signed off and we finally got it signed into law. It was just signed into law by the president on January 2.

Leech: Wow. When you are checking in with all these people and doing all of this due diligence, is it always through your legislative champions, or do you yourself go to the individual offices to explain what is in the bill?

Richardson: It is mostly staff work, meeting with staff. It is the staff on the Hill who make the wheels go round. The decisions are made much further up the chain, by the members of Congress, by leadership, but all of the ground work and all of the ins and outs of dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s are done by the staff.

Leech: You must be in constant communication.

Richardson: Yes, absolutely. We build relationships with the staffers and we know what their expertise is, what their strengths are, and—depending on whom they are working for—we also get to know what their political inclinations are and where their policy interests lie, and we use that as well.

Leech: What percentage of your days is taken up with talking with staff and getting to know them versus other things you might do, like doing research, or writing, or working on something internal to the FOP?

Richardson: I would say that the bulk of my day—maybe sixty or seventy percent—is spent writing, be it a simple letter of support for a particular bill, an alert for our membership about the introduction of a bill or about movement on a bill, or an invitation for a member of Congress to speak at a function.

Most of the rest of the time is focused on the Hill. I’ll be on the phone with the Senate Judiciary Committee—the folks I work with all the time. Sometimes I am calling just to check in. Sometimes I am seeing what their agenda is going to be for next week. The more staff an organization has, the more lobbyists can be proactive and can get out of the office and go look the congressional staffers in the eyes and talk with them. When staffing levels are lower, lobbyists are more confined to the office, and e-mail, and the telephone. Many staffers now prefer electronic communications to finding a place to meet in a small congressional office.

Leech: Interesting.

Richardson: With the draconian changes to the ethics guidelines and rules of the House and Senate, it’s not like it was ten or twelve years ago when a lobbyist and a staffer who knew each other both in the office and away from the office could get a cup of coffee in the morning or have a beer after work. You can’t do that anymore. It’s just too much of a hassle.

Leech: How has that affected you and the FOP?

Richardson: It is hard to get to know new staff persons as well as I know the dozen or so that have been around since I started in Washington. I had a good friend who worked for a member of Congress. We would hang out very frequently after work and almost never discussed business. This is, I think, something else that most folks don’t understand. When we are not working, we don’t want to work. There is, obviously, shop talk because that’s what you do, but you are not taking a guy to a baseball game or to grab a beer after work because you want to lecture him on the merits of concealed firearms.

Leech: Although you still could do that if the staffer paid his own way.

Richardson: Oh yes, absolutely. Anyway, my friend was off the Hill for a while and then when he returned to the Hill, he had to fill out more paperwork than he knew what to do with just if we went out for a beer after work. And so it is hard to get new staffers outside the office so that you can get to know them.

Leech: But you wouldn’t have to fill out the paperwork if he paid for his own beer, right?

Richardson: Yes, that’s true if everybody is on their own dime but there is still some negative attention. Staffers are very cognizant of any appearance of any impropriety.

Leech: You were talking a bit earlier about the amount of time you spend writing. Could you expand on that and walk me through an average day? What does a day look like to you?

Richardson: The first thing every day is reading the news from CQ, Congressional Quarterly, a service that monitors Congress. Then I check my e-mails on my way into work.

Leech: How early do you start?

Richardson: This town wakes up early, but I live about fifty miles from Capitol Hill, so my day in the office starts about nine thirty. CQ will let me know what the agenda is for the committees in the House and the Senate so that I can be prepared to respond to anything that is happening. I scan the news to see if our issues are being talked about so that I am prepared for the day. Normally, that day will mostly consist of the writing I’ve got to do. Then I try to do at least one call to someone I don’t need anything from, just to keep connections open. Sometimes I am able to do it: my rule is three people a week.

Leech: A congressional staffer or somebody from another organization?

Richardson: Yes, just to check in just to see what’s going on. More often than not, the communication will be electronic, but for the people I work with quite frequently, I will pick up the phone and see if I can get them on the horn.

Then I also will be working on whatever issue we have at the moment that is near to being introduced, preparing for a committee markup, or trying to get a floor vote.

Because the FOP has such a broad swath of issues, depending on the week I could be talking to the HELP [Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions] Committee in the Senate, the Education and the Workforce Committee in the House, the House Judiciary Committee, or the Senate Committee on Homeland Security. It could be a whole mix of things.

Leech: We were up to the afternoon in your day. When do you usually head home?

Richardson: Normally, my day ends about six thirty. That’s the last train out. There are sometimes events that occur after regular working hours, such as events with other organizations for members of Congress, so sometimes my day can stretch into the evening. The evening events are not as frequent as they used to be—again because of the problems with out-of-office interaction, and because the economy stinks and there are not a lot of organizations willing to pay for those large events.

But especially now, with communication being what it is, I am never really off duty. I have my Blackberry with me all of the time. If I can get to the Internet, I can do my job. I was on the phone and doing a lot of electronic communication over the holidays because, in addition to the fiscal cliff, and the tax, and everything else, there was a piece of legislation introduced that directly affected the FOP. The Safer Act was introduced by Senator John Cornyn, and similar legislation was introduced by Senator Patrick Leahy. This legislation would create a public DNA registry using information from rape kits in sexual assault cases. It would beef up the Debbie Smith DNA Act and there was some hope that we could get it through before the congressional session ended, because it began as a bipartisan effort and there was a lot of broad-based agreement. But, unfortunately, we were not able to do it.

Leech: And that issue kept you working right up through the end of the year?

Richardson: Yes, it’s the first time I can remember trying to have a policy discussion at seven p.m. on New Year’s Eve.

Leech: Ouch. That sort of leads into a question I wanted to ask you: whether you feel that being a lobbyist is conducive to family life?

Richardson: It is. When I was younger, I was not as responsible with my time, but now I think it’s like any other job. You’ve got to make smart decisions about your time. I have a pretty long commute and that does affect home life because sometimes I am not home until eight p.m. because it’s an hour and fifteen- or twenty-minute ride home, but we make do. I don’t think there are any particular challenges for home life in lobbying or legislative advocacy.

Leech: Do you have kids?

Richardson: I do. One of each, ten and nine.

Leech: What do you think is the best thing about your job? What do you like the most?

Richardson: Dealing with government can be incredibly frustrating, but when you get something done, it is very fulfilling because you have passed a law. My mom used to say, “Let’s not make a federal case out of this,” but that’s what I do every day. I make a federal case out of something. When you get it done and you see how many officers are appreciative of the objective you achieve, it’s a very positive feeling. I talk to three or four officers a week who call in with questions about the Law Enforcement Officer Safety Act that exempted active officers from the concealed-carry laws, and they are always so appreciative of what the FOP did for them in making that change federal.

Leech: It sounds like you have a lot of interaction with FOP members.

Richardson: Yes, the FOP differs from a lot of other labor organizations, which are very top-down, leadership-driven. The decisions are made at that upper level. The FOP, by contrast, is organized at the local level, so the local president is sovereign in that locality for decisions about public safety policy. The same thing is true at the state level. State laws are sovereign to state organizations. The national FOP can’t come into New York, for example, and take a position on state firearms legislation. We have a constitution and bylaws that prohibit us from doing that. The national FOP only deals with issues and matters that affect all three hundred and thirty thousand of our networks. We don’t do local contract negotiations, although we do have support staff that will assist.

Leech: I know the FOP does a member fly-in day. Why do you do that and what does it look like when you are doing it?

Richardson: We do it annually. It started the year before I got here. We call it our Day on the Hill, even though it’s about half a week. We ask all of our members who can to come to Washington, DC. We ask them to make appointments with their senators and their representative. We spend the first day briefing them on lobbying strategies, lobbying tips, and the legislation that we are asking them to talk about—our top priorities and whatever pending issues are topical. For example, last year, the House was scheduled to vote on a funding bill that affected the COPS office, which is the Community Oriented Policing Services office that administers the grants to localities that assist them in hiring new officers. That vote was that week. We had about two hundred officers in here and there were twenty-four, maybe as many as thirty votes, that we flipped and I think that’s just because we were here in town.

Leech: Yes, because the members of Congress were hearing from their constituent police officers.

Richardson: In any case, we brief the officers on Monday on what they need to know. For that whole week, this office is not doing anything else proactive. We are on standby for the visiting officers. We are here to answer questions for our members and from staff because sometimes staff is going to be hearing about this issue for the first time from officers that patrol our communities. It’s a great time. We often get a spike in co-sponsorships of a piece of legislation we are interested in, and for at least the next couple of weeks, those congressional offices are going to be talking and thinking about these issues and responding to the constituents who took their time and spent their money to come to DC.

Leech: What about the popular opinion about lobbyists? How would you say that reality is different from what most people think lobbyists are and what lobbyists do?

Richardson: The perception is a little off. We are not as bad as lawyers, for example. We are paid to represent a certain point of view or a certain group of constituents, so no matter what we are lobbying for, someone is paying us to do that job, and I think lobbying is the sign of a healthy democracy, of healthy public interaction. What can muddle things up is when people make bad decisions. That happens in any career or industry, but with lobbying it is magnified. I think the degree of offense is increased because lobbyists are perceived as having special privileges because of their access to members of Congress.

Everybody has a lobbyist in Washington. When I first got to town, I had to commute past an entire building for the National Snack Foods Association. Not only do snack food manufacturers have a lobbyist—they have a whole building. Everyone has a point of view and if you are organized enough, you can get professional representation to express that message in DC.

Leech: What’s the worst thing about your job? What don’t you like doing?

Richardson: The only thing I really hate is my commute. I’m sure that’s true for about two million people that live and work around this city.

Leech: I’ll bet that’s true. Why do you live so far out?

Richardson: Mostly the economy. I started out in Arlington, then Alexandria, then Prince William, and I think I might keep going, so I will be in Richmond before too long. My wife is a teacher, so her job also was an issue. We just kept migrating further and further south. It’s nice when I’m there. It’s a great area, great neighborhood. I can’t think of a better place to live in the area, but it’s a long commute every day.

Leech: Do you manage to get much work done on the train?

Richardson: I try to avoid it if I can. That’s my decompression time. During the morning commute I review any early e-mails that come in. CQ does what they call alerts, so when a bill that I’m interested in is set up for action or it shows up in a news story, I get those e-mails. So I probably spend about half my morning commute interacting through my phone. But at the end of the day, I turn the lights out at six thirty unless there is something happening. I try to end my workday at that time. It doesn’t always work.

Leech: What are the skills and qualities that someone needs to do a good job as a lobbyist?

Richardson: Be happy and be personable. You have to like to talk. You have to like to interact. You have to have a great deal of patience. One of the not-very-fun parts of the job is that Washington attracts a lot of conflicting personalities. That’s just how it is. You also have staffers who are supposed to protect their bosses by not letting lobbyists talk to them. You have to have a lot of patience.

Depending on whom you work for, you may have to be willing to advocate for something that you don’t feel very strongly about in your heart of hearts. I came from the Senate Republican Policy Committee when I was hired by the FOP, and two months later, they endorsed Bill Clinton for reelection. I had the twitches and the fits for the first six months I was here. I went from writing Republican screeds to coordinating with the Clinton campaign. It was quite a culture shock. You have to be open-minded in that way. If you can’t, then you are better off working for an organization that represents something that you believe in very strongly. If weapons are your thing, then you’ll want to work for the NRA [National Rifle Association] or the Gun Owners of America, or if you’re interested in social issues go to the Family Research Council if you are conservative and the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] if you are not.

An organization like the FOP is not really “special interest.” It’s the man on the street with the badge and the gun who is keeping your family safe. I think it’s easier because everything we do is directed by our members who say, “This is what I need to get this job done well and get it done safely.” I’m much more comfortable with whatever that agenda is, because it is to support the officers.

Leech: Your undergraduate degree was in political science but you also had some training in writing. Do you find that’s a help in your work?

Richardson: Yes, it was very helpful. I was a double major in political science and English professional writing. I have always had some talent in writing, and I was able to apply it here. I think that’s one of the things that made me stand out early at FOP. I had talent as a writer and that has improved. Ironically, the only English course I did not get an A in as a college student was a course in writing for the government and judiciary. I barely passed it.

Leech: That’s very funny.

Richardson: The professor and I had very deep philosophical issues and I barely made the final exam. I was not very responsible with my time as a younger man.

Leech: Do you have any advice for people who are college students now?

Richardson: Anyone who is interested in public policy, political science, or politics should spend some time looking at the advocacy side. Whether it is because you are going before your zoning board in your local community or because you want to make the world safe by banning the use of land mines internationally—whatever that cause is or whatever is important to you, you will need to know what it takes to advocate effectively.

I apply the same principles I use on the Hill to every other aspect of life, all the way down to meeting with my kids’ teachers or principals. If I have an objective, I use the advocacy strategies there. Anything that you are doing—regardless of whether it is professionally as a lobbyist, or just getting things done around the house, or in your life dealing with other folks—the advocacy approach is going to work. There is some application for it.

Leech: When you say the advocacy approach and how you are using it in other aspects of your life, what in particular are you talking about?

Richardson: Know what you want to get before you sit down. That’s the biggest thing. Have your goal, have a goal that is achievable, and then don’t let up until you have achieved that goal, regardless of how long it takes. You will need some patience sometimes, but if you know what you want to get, there is no reason you can’t get it.