CHAPTER 11

Building Strong Brands

Alexander Chernev

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare famously wrote: “What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” While Shakespeare's insight may have been true centuries ago when he penned his masterpiece, today it is no longer the case: A name is not always just a name. As it becomes a brand, the name gains the power to influence our perceptions of the world around us, determine what we choose to buy, how we experience different products and services, and how happy we are with their performance. Because of their unique ability to influence behavior, brands have become a key driver of customer value. In this chapter, we will explore the role of brands as a marketing tool, the importance of creating a meaningful brand image, the ways in which brands create customer and company value, and the role of brand equity and brand power in brand valuation.1

The Brand as a Marketing Tool

Brands have a long history as a means of distinguishing the goods of one company from those of another. Some of the earliest known brands were used to mark the identity of a good's maker or owner. These simplest forms of branding were observed in the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Crete, Etruria, and Greece. During the Roman Empire, more distinctive forms of branding, including the use of word marks in addition to graphics, began to emerge. The importance of brands dramatically increased by the end of the nineteenth century when the proliferation of mass‐produced, standardized products—a direct consequence of the Industrial Revolution—created the need for unique marks to help consumers distinguish between these products. As manufacturers began producing on a larger scale and gained wider distribution, they started engraving their mark into the goods to distinguish themselves from their competition.

Along with these changes, the nature of brands was transforming from simply marking the origin of the product to identifying its maker and serving as a symbol of product quality. Indeed, many brands started as product descriptors designed to identify their maker to help retailers manage their inventory. Over time, these products and services gained a reputation in the market, and customers not only sought them out but were willing to pay a premium for them. The name and the other identifying characteristics—such as the logo, motto, and packaging—acquired a meaning that went beyond simply labeling these products and services to imply characteristics and benefits that were not readily observable.

Nowadays, brands are ubiquitous. Their use extends beyond physical goods such as food products, cars, and pharmaceuticals. Brands are used to designate product ingredients that consumers never buy directly (Teflon, Gore‐Tex, and Vibram). Brands can also be used to identify services (Netflix, Expedia, and Uber), companies (Unilever, Walmart, and Starbucks), and nonprofit organizations (NHL, The Nature Conservancy, and American Red Cross). Brands can also designate administrative units (countries, states, and cities), geographic locations (Champagne, Cognac, and Roquefort), and events (Olympic Games, Wimbledon, and Super Bowl). Brands can identify individuals (Lady Gaga, Madonna, and Michael Jordan), groups (music groups, sports teams, and social clubs), and ideas and causes (education, social justice, and health). The use of brands is not limited to consumer markets. Business‐to‐business enterprises have built strong brands that span industries including consulting (McKinsey & Company, Boston Consulting Group, and Accenture), commercial equipment manufacturing (Boeing, DuPont, and Caterpillar), and software solution services (SAP, Oracle, and Rakuten).

The ubiquity of brands in all aspects of business life stems from their ability to create market value. Not only do brands play a role in helping customers identify the company's offerings, but they can also create value above and beyond the value created by the product and service aspects of these offerings. In this context, brands can be defined as follows:

- The brand is a marketing tool used to identify an offering, differentiate it from similar market offerings, and create distinct market value above and beyond that created by the other attributes of the offering.

The role of brands is often confused with that of products—partly because many managers confound product and brand management decisions in their daily activities. Yet, product management and brand management are two distinct activities that are unified by the common goal of creating market value. The difference between products and brands can be illustrated by the following example.

Consider a cereal company introducing a new offering. Let's say the company decides to target health‐conscious families with young children with the value proposition of a tasty, healthy cereal that both parents and their children can enjoy. Once this strategy is in place, the next step involves creating the actual cereal that will be offered in the market, which is defined by seven tactical decisions: product, service, brand, price, incentives, communication, and distribution. Here, the product and brand decisions are two distinct attributes of the offering that follow the same overarching strategy.

When designing the product, a manager must develop an appropriate product strategy by identifying the key benefits that the product will create for target customers. In the cereal example, product benefits might involve factors such as taste and nutrition. To deliver these benefits, a manager makes a series of tactical product‐based decisions that involve specific aspects of the cereal, such as its nutritional value (calories, sugar, fiber, sodium, protein, and vitamins) and taste (flavor, texture, crunchiness, and crispiness).

In addition to deciding on the properties of the cereal, a manager must decide how to brand the product. To this end, a manager must create a unique identity that is associated with the company's product to inform potential buyers that this specific product was created by a particular company rather than by one of its competitors. In addition, the manager might want to create an identity that not only differentiates its product from the competition's but also adds value to customers’ experience with the product.

In the cereal example, the brand might aim to create the psychological benefit of building a relationship with customers so that it becomes an integral part of their breakfast ritual. To this end, the manager might create a character that will capture the personality of the brand, thus helping consumers easily recognize the company's cereal and at the same time connect with the brand on an emotional level. For example, Kellogg's Frosted Flakes uses Tony the Tiger as a brand character to uniquely identify this cereal in the grocery store and foster an emotional connection with the brand. Thus, the brand creates value that enhances the value created by the product. Indeed, when cereal manufactured by different companies looks and tastes alike, the brand becomes the key distinguishing factor. Furthermore, while enjoying the taste of the cereal, customers are unlikely to form an emotional bond with the product unless it is associated with an image that carries relevant meaning for these customers.

Product and brand decisions require different types of expertise. In the cereal example, product‐focused decisions call for knowledge pertaining to human nutrition, food manufacturing technologies and processes, as well as consumer food preferences. In contrast, brand‐focused decisions require in‐depth understanding of the customer, including higher‐level customer needs such as the need for self‐expression, relationships, and belonging. The different competencies involved in product and brand management often lead to separating these two activities into discrete product and brand management functions and assigning these functions to different managers, who work together to develop successful market offerings.

Although brands are designed and managed by companies, their power stems from the image they create in people's minds. “Products are made in a factory, but brands are created in the mind,” memorably noted Walter Landor, a brand pioneer whose firm created identities and logos for some of the world's largest corporations including Coca‐Cola, Levi Strauss, Fujifilm, and 3M. Because brands are created in people's minds, they—unlike products—cannot readily be established in one country and exported to another. Instead, they need to be cultivated in each market to create a meaningful image in customers’ minds.

The Brand as a Mental Image

The ultimate goal of a company's branding activities is to create a brand image—a mental image that exists in people's minds and reflects their thoughts, beliefs, and feelings about the company and its offerings. Thus, unlike the term brand—which is often used to designate specific attributes such as name, logo, and motto that identify the company and its offerings—the term brand image refers to the network of brand‐specific associations that exist in people's minds. It reflects how customers view a particular brand through the lens of their own set of values, beliefs, and experiences. Simply put, the brand image reflects the way people perceive the brand.

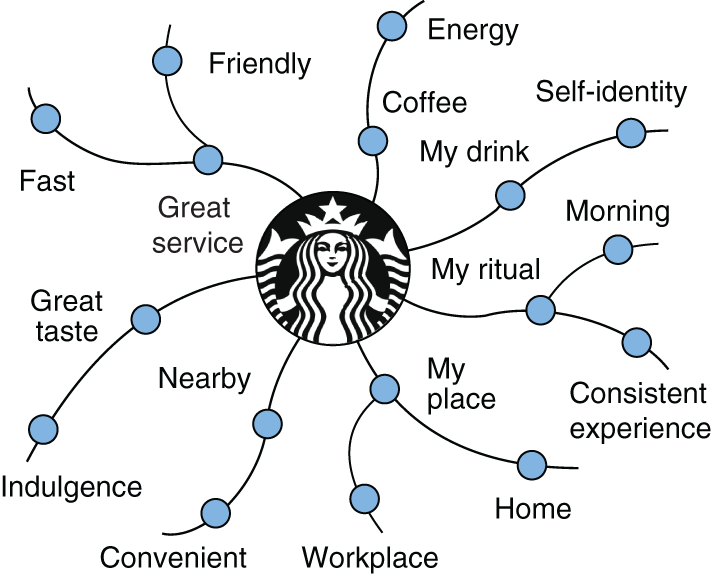

Brand image can be visually represented as an association map delineating the key concepts linked to the brand name. Figure 11.1 illustrates a streamlined brand association map representing a particular person's image of the Starbucks brand. Here, the nodes represent the different concepts related to the brand in this person's mind. The nodes closer to the brand name indicate thoughts that are directly associated with the brand, and the nodes that are farther away indicate the secondary associations that are less prominent in a customer's mind.

The type of associations brands evoke—as well as the breadth, strength, and attractiveness (positive vs. negative) of these associations—reflect the degree to which a given brand has successfully created a relevant, well‐articulated, and positive image in a customer's mind. The stronger the brand, the greater the number of relevant benefits, usage occasions, experiences, concepts, products, and places associated with it—and the stronger and more positive these associations are.

FIGURE 11.1 Starbucks Brand Association Map

Source: Alexander Chernev, Strategic Brand Management, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: Cerebellum Press, 2020).

Ideally (from a company's standpoint), the brand image that exists in the mind of each of its customers should be consistent with the image the company aims to project. In reality, however, this is not always the case. Because the brand image exists in a customer's mind and stems from this customer's individual needs, values, and knowledge accumulated over time, the same brand might evoke different brand images in different individuals. For example, some might associate the Starbucks brand with handcrafted espresso coffee drinks, while for others it might represent a part of their daily routine, and yet others might think of Starbucks as a place to meet with friends.

Given the idiosyncratic nature of customers’ experiences, a company's ability to create a consistent image of its brand in customers’ minds is often limited to identifying and communicating the key concepts that it would like customers to associate with the brand. Because the actual image formed in customers’ minds varies based on customers’ unique interactions with the brand, having a clearly articulated brand strategy can help the company overcome the diversity of customers’ individual experiences and build a brand image that reflects the essence of the company's brand.

The brand image is intricately related to the value created by the brand, such that the value of a brand stems from the image that exists in the minds of its customers. In this context, the brand image reflects the meaning of the brand: what the brand is and what it is not. The brand value, on the other hand, reflects the benefits and costs that customers associate with this meaning. The brand image answers the question What is Brand X? In contrast, the brand value answers the question What can Brand X do for me? Thus, creating a meaningful brand image is crucial for a brand's ability to create market value.

How Brands Create Value

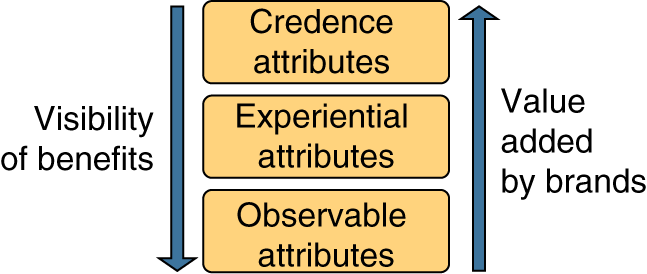

A brand's ability to create value can be related to the transparency of the benefits defining a company's offering. This is because not all aspects of a company's offering can be readily observed by customers. Some attributes are associated with greater levels of uncertainty and, as a result, their benefits are more difficult to evaluate than those of other attributes characterized by a greater level of transparency. Based on the level of uncertainty associated with their performance, an offering's attributes can be classified into one of three categories: observable, experiential, and credence.2

Observable attributes provide benefits that can be readily identified and evaluated. These attributes are associated with the least amount of uncertainty and are typically identifiable through inspection before purchase. For example, the size and shape of a toothpaste tube, the color of a car, and the type of cuisine offered by a restaurant are observable attributes.

Experiential attributes carry greater uncertainty and are revealed only through consumption. For example, the flavor of a toothpaste, the comfort of a car, and the taste of a meal in a restaurant are experiential attributes because their performance cannot be assessed by merely observing the offering.

Credence attributes have the greatest amount of uncertainty, and their actual performance is not truly revealed even after consumption. For example, the cavity prevention benefits of a toothpaste, the safety of a car, and the calorie count of a restaurant meal are credence attributes because even after experiencing the offerings, customers are unable to evaluate their performance.

The distinction between observable, experiential, and credence attributes is important because it determines the role a brand can play in creating customer value. The general principle here is that the greater the amount of uncertainty associated with an offering's benefits, the greater the role a brand can play in communicating these benefits. Indeed, communicating observable benefits is relatively straightforward and merely involves informing target customers about the properties of the offering's attributes. Likewise, communicating experiential attributes can readily be achieved by letting customers experience the offering using means such as trials and free samples. Communicating credence attributes, however, is more complicated and requires that customers trust the offering to deliver the promised attributes. Such trust can be achieved by building a reputable brand that can support the company's claims about the unobservable performance of its products and services.

There is an inverse relationship between the visibility of benefits and the importance of brands as a means of communicating these benefits: Less visible benefits require heavier reliance on brands to create market value. As a result, the greater the importance of unobservable benefits, the greater the role brands play in creating market value (Figure 11.2). Not only can a brand convey an offering's invisible benefits, it can also make these benefits more prominent in people's minds. In doing so, a brand's function goes beyond simply identifying a company's offering and differentiating it from the competition to create customer value by revealing this offering's performance on observable attributes. Brands create value by making the invisible visible.

FIGURE 11.2 Benefit Visibility and Brand Impact

Source: Alexander Chernev, Strategic Brand Management, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: Cerebellum Press, 2020).

Consider the success of evian. Following the opening of its first bottling facility in 1826, evian managed to become the top‐selling premium spring water worldwide in an industry that at the time was perceived as a commodity. Evian achieved this by positioning its brand to address an unmet market need: Mothers were concerned about the purity of the tap water they were using to feed their infants. One of the reasons for their concern were the chemicals used to purify the tap water, which could be readily tasted when drinking it. Evian water, with its bland taste, was the perfect product to alleviate this concern because the lack of tap‐water taste was viewed as a sign of purity. Evian made the purity and mineral content of water—attributes that at the time were not prominent in people's minds—important factors in the buyer decision process, and positioned its brand as the best at delivering on these two benefits. Thus, by making the invisible attributes of its offering prominent, evian was able to transform the way customers thought about drinking water and establish the superiority of its brand on these attributes.

Similar to evian, Michelin established its brand by emphasizing the importance of a previously obscure aspect of automotive tires—reliability. With its motto Because So Much Is Riding on Your Tires, Michelin brought to light the risk associated with buying tires that might be unreliable. In the same vein, DieHard emphasizes the longevity of its batteries, DeWalt underscores the durability of its professional tools, McDonald's focuses on the consistency of its meals, and Papa John's promotes the freshness of its pizza ingredients. Pharmaceutical companies often launch brands designed to solve problems that were invisible to customers until the company made these problems prominent. The branding strategies employed by these companies are effective because when customers cannot readily assess the benefits of the available offerings, they tend to rely on a brand's promise to deliver on the unobservable benefits and use the brand as a key factor in making their choice.

Brands as a Means of Creating Customer Value

The primary purpose of brands is to create value for their target customers and, by doing so, create value for the company managing the brand. Without customer value, there is no value to be captured by the company. Brands can create customer value on one or more of the three key dimensions: functional, psychological, and monetary.

Functional Value

Functional value reflects the benefits and costs directly related to an offering's practical utility such as performance, reliability, durability, compatibility, and convenience. Brands can create functional value in two ways: by identifying a company offering and by signaling the offering's functional performance.

Identifying the company offerings. Brands enable customers to identify a company's products and services and distinguish them from those of its competitors. For example, if Tide laundry detergent was not associated with a unique brand, customers would have difficulty locating it and would have to examine the ingredients of many detergents to ensure that the product they purchase is indeed the Tide detergent produced by Procter & Gamble. The identification function of brands is particularly important in the case of commoditized products that are similar in their appearance and performance.

Signaling performance. In addition to identifying the offering, brands can inform customers about the functional performance of the products and services associated with the brand. For example, the Tide brand signals cleaning power, the Crest brand signals effective cavity protection, and the DeWalt brand signals durability. Not only can brands inform customers about the performance of products and services, but they can also change the way customers experience these products and services. For example, the taste of beer, the scent of perfume, and even the effectiveness of a drug might be influenced by customers’ knowledge of their brands.

Psychological Value

Psychological value reflects the mental benefits and costs of the offering, such as the emotional experience provided by the offering and its ability to signal a customer's social status and personality. Psychological value is often the key source of the market value created by brands. Indeed, because brands evoke specific associations in a customer's mind, they can convey a wider range of emotions and deeper meaning than the other attributes of the offering. Specifically, the psychological value created by brands stems from three types of benefits: emotional, self‐expressive, and societal.

Emotional value. Brands can create emotional value by evoking an affective response from customers that is typically associated with positive emotions. For example, Allstate Insurance Company (“You're in Good Hands with Allstate”) aims to convey peace of mind with its brand, and Hallmark (“When You Care Enough to Send the Very Best”) evokes the feeling of love and affection.

Self‐expressive value. Brands can create self‐expressive value by enabling individuals to express their identity. For example, brands like Harley‐Davidson, Diesel, and Tommy Bahama stand for different lifestyles, enabling consumers to express their unique personality by displaying these brands. In addition to allowing consumers to express their individuality, brands like Rolls‐Royce, Louis Vuitton, and Cartier create psychological value by enabling their customers to highlight their wealth and socioeconomic status.

Societal value. Brands can create societal value by conveying a sense of moral gratification from contributing to society. For example, brands like TOMS, Patagonia, Product Red, UNICEF, Doctors Without Borders, and Habitat for Humanity that represent humanitarian causes create customer value by taking a stand on relevant social issues and implementing a variety of socially responsible programs.

Monetary Value

In addition to creating functional and psychological value, brands can also create monetary value. Monetary value reflects the financial benefits and costs of the offering, such as its price, fees, discounts, and rebates, as well as the various monetary costs associated with using, maintaining, and disposing of the offering. Specifically, brands can create two types of monetary benefits: signaling price and generating financial value.

Signaling price. Brands can signal the overall level of prices associated with the company's products and services. For example, the Walmart brand conveys the idea of low prices, fostering the belief that its offerings are priced lower than its competitors’. The price image conveyed by a brand is particularly important when buyers are unaware of the competitiveness of the price of a given offering and, in such cases, they often rely on the brand to infer the attractiveness of an offering's price.

Financial value. In addition to signaling an offering's monetary value, brands can also carry inherent monetary benefits, which are reflected in the higher price of branded offerings on the secondary market. For example, a Louis Vuitton handbag commands a much higher resale price compared to a functionally equivalent unbranded handbag. In fact, the financial benefit of brands is one of the key factors in valuing alternative investments such as wine, watches, and automobiles.

Brands as a Means of Creating Customer Value: The Big Picture

The three dimensions of customer value—functional, psychological, and monetary—and the specific ways in which brands can create value on each of these dimensions are summarized in Figure 11.3. The value added by brands on each of these dimensions depends on a variety of factors such as the specific product category, customers’ familiarity with the attributes of the offering, and the degree to which the offering's performance on different attributes is readily observable. The lower the customers’ expertise and the less observable the offering's performance on attributes that are important to these customers, the greater the potential value created by the brand.

Not every brand can create value on all three dimensions. In fact, positioning the brand on some of the value dimensions might greatly diminish this brand's ability to create value on other dimensions. For example, a brand signaling a monetary benefit, such as low price, might not be credible in signaling high levels of product performance and conveying wealth and social status. In this context, the different types of customer value can serve as a guide to developing a brand's value proposition rather than be regarded as a requirement that a brand create value for customers on each of the three dimensions.

FIGURE 11.3 Brands as a Means of Creating Customer Value

Source: Alexander Chernev, Strategic Brand Management, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: Cerebellum Press, 2020).

Brands as a Means of Creating Company Value

In addition to creating value for customers, brands can create value for the company. The ability of the brand to create company value is important because it enables the company not only to recoup the resources spent in designing and communicating the brand but also to create incremental value stemming from the brand. There are two main dimensions on which brands can create company value: strategic and monetary.

Strategic Value

The strategic value created by brands reflects the nonmonetary benefits that a company derives from associating its products and services with a given brand. Some of the key strategic benefits include bolstering customer demand, amplifying the impact of the other marketing tactics, ensuring greater collaborator support, and strengthening the company culture.

Bolstering customer demand. Because brands create customer value, they generate incremental demand for a company's offerings. For example, a customer who is not interested in an unbranded product might be interested in a branded version of the same product because this customer finds the brand meaningful and relevant. In addition to increasing the attractiveness of the company's offerings, brands might facilitate the usage of the company's offering, as customers are more likely to consume the branded offering more frequently. Offerings associated with an attractive brand are also more likely to encourage customer advocacy, which, in turn, is likely to further promote sales. For example, Zappos, Zara, and Apple have many customers who are passionate about the brand and help expand the demand for offerings associated with these brands.

Amplifying the impact of other marketing tactics. In addition to directly bolstering customer demand, brands can increase the effectiveness of the other attributes defining the company's offering. Thus, brands can enhance customer perceptions of product performance by making branded products appear more powerful, reliable, durable, safe, attractive, tasty, or visually appealing than their unbranded counterparts. For example, people tend to think that a drug is more effective if it is associated with a reputable pharmaceutical brand. Because brands create incremental customer value, companies tend to charge higher prices for branded products than for unbranded products. For example, Morton‐branded salt commands a substantial price premium over the unbranded version, even though both contain the same ingredient. In addition to finding branded products more attractive and paying extra for them, customers are also more willing to search for the branded product across distribution channels and bypass more convenient retailers that do not carry their favorite brand—even when a functionally equivalent substitute is readily available. Customers are also likely to react more favorably to incentives and communication from a brand they patronize than those from identical unbranded products.

Ensuring greater collaborator support. Strong brands can create value for the company by securing greater support from its collaborators. For example, strong brands give manufacturers power over retailers, enabling them to negotiate more advantageous agreements, resulting in a better distribution network and greater promotional support such as on‐hand inventory, product placement, and sales support. In the same vein, retailers with a strong brand can command greater support and better margins from manufacturers of products that are either unbranded or associated with weak brands.

Enhancing the corporate culture. Strong brands can help build, enhance, and sustain the company culture. This is because a brand can create a strong sense of identification among its employees, increase their morale, and bolster their teamwork. Furthermore, brands can facilitate the recruitment and retention of skilled employees. This is because employees often place a premium on working for companies whose brands resonate with their own needs, preferences, and value systems. Thus, companies with strong brands find it easier to attract and retain talented employees. In fact, employees are often ready to sacrifice part of their compensation and accept a lower salary to work for a company with a favorable brand.3

Monetary Value

Monetary value is directly linked to a company's desired financial performance and typically includes factors such as net income, profit margins, sales revenue, and return on investment. Monetary value is the most common type of value ultimately sought by for‐profit companies. Brands can create monetary value for the company in several ways: by generating incremental revenues and profits, increasing company valuation, and creating a divestable company asset.

Generating incremental revenues and profits. A brand's ability to generate higher sales revenues and profits stems from customers’ reaction to the brand, including their greater willingness to buy the branded offering as well as pay a premium for this offering compared to the unbranded version of the same offering. The incremental stream of revenues associated with the brand is the most important direct source of monetary value that benefits the company on an ongoing basis. In addition to the increase in revenues stemming from customers’ affinity for the brand, a company might also be able to negotiate better financial terms with its collaborators, such as distributors and retailers, who are likely to benefit from the strength of the company's brand.

Increasing the valuation of the company. Brands’ ability to generate incremental net income can, in turn, enhance the monetary value of the company, such that companies with strong brands receive higher market valuations. In fact, many companies have managed to build brands that are worth more than the value of their tangible assets. Apple, Coca‐Cola, Disney, McDonald's, and Nike brands are each estimated to be worth tens of billions of dollars, making these brands one of their company's most valuable assets. The combined value of the top 100 brands is estimated to be in excess of a trillion dollars. We discuss the different approaches to assessing the value of a brand later in this chapter.

Creating a divestable company asset. In addition to contributing to a company's valuation, brands might generate additional value for the company if they are acquired by another entity. In particular, brands with names that are distinct from the parent company's brand might have significantly higher value when acquired by another company with better opportunities to unlock the true value of the brand. For example, over time Procter & Gamble divested many of the brands it helped to build and manage, including CoverGirl, Clairol, Duracell, Folgers, Jif, and Pringles, collecting tens of billions of dollars in the process, most of which were attributable to the power of these brands.

Brands as a Means of Creating Company Value: The Big Picture

In the world of rapidly commoditizing products and services, brands are becoming the new frontier of competitive differentiation and the key source of company value. The two dimensions of company value—strategic and monetary—and the specific ways in which brands can create value on each dimension are summarized in Figure 11.4. The monetary value created by the brand is often readily observable and, as a result, is frequently given priority in evaluating a brand's performance. The strategic value of the brand, although often invisible, can supplant the direct monetary value of the brand and, therefore, should be carefully nurtured to realize its full potential.

Understanding the ways in which brands create value for the company is important because it enables managers to better measure the effectiveness of their brand‐building activities. Knowing the value a brand creates for the company also enables managers to frame brand‐building costs as an investment in a value‐creation asset rather than merely as an ongoing marketing expense with no residual value. As the popular saying, commonly attributed to Peter Drucker, goes, “What gets measured, gets managed.” Accordingly, the following section offers a more detailed discussion of assessing the company value created by brands, focusing on the concepts of brand equity and brand power.

FIGURE 11.4 Brands as a Means of Creating Company Value

Source: Alexander Chernev, Strategic Brand Management, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: Cerebellum Press, 2020).

Brand Valuation

A company can benefit from having an accurate estimate of the value of its brands for several reasons. Knowing the monetary value of a brand is important in mergers and acquisitions to determine the premium over the book value of the company that a buyer should pay. Knowing the monetary value of its brand(s) is also important to determine the value of the entire company for stock valuation purposes. Brand valuation is also important in licensing to determine the price premium that brand owners should receive from licensees for the right to use their brand. Having an accurate estimate of the value of the brand also matters in litigation cases involving damages to the brand to determine the appropriate magnitude of monetary compensation. Assessing the value of the brand is also important for evaluating the effectiveness of a company's brand‐building activities as well as for deciding on the allocation of resources across brands in a company's portfolio.

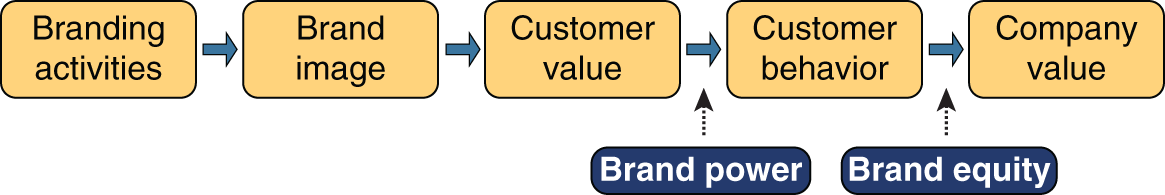

To succeed in building strong brands, a company must have a clear understanding of how the brand creates market value, as well as the metrics and processes for assessing the value of the brand. The two aspects of brand value—brand equity and brand power—are outlined in more detail below.

Brand Equity as a Source of Market Value

Brand equity is the monetary value of the brand. It is the premium that is placed on a company's valuation because of brand ownership. The monetary value of a brand is reflected in the financial returns that the brand will generate over its lifetime. Understanding the concept of brand equity, managing its antecedents and consequences, and developing methodologies to measure brand equity are of utmost importance for ensuring a company's financial well‐being.

The issue of brand valuation came into prominence in the 1980s when the wave of mergers and acquisitions, including the $25 billion buyout of RJR Nabisco, served as a natural catalyst for the increased interest in brand valuation and the development of more accurate brand valuation methodologies. Because the value of the brands owned by a company is not reflected in its books,4 setting a fair price for brand assets that a firm has built over time is of utmost importance, especially given the fact that the value of a company's brands could exceed its tangible assets.

Despite the importance of brand equity, there is no single universally agreed‐on methodology for its assessment; rather, there are several alternative methods, each emphasizing different aspects of brand equity. Three common approaches to measuring brand equity are the cost approach, the market approach, and the financial approach. All of these approaches view brands as separable and transferable company assets that have the ability to generate a stream of revenue. Where these approaches differ is in conceptualizing the sources of brand equity and the reliance on different methodologies to quantify the value of the brand.

The cost approach involves calculating brand equity based on the costs involved—marketing research, brand design, communication, management, and legal costs—to develop the brand. The cost method can be based on the historical costs of creating the brand by estimating all relevant expenditures involved in building the brand, or it can be based on the replacement cost—the monetary expense of rebuilding the brand at the time of valuation.

The cost approach is intuitive and is commonly used for evaluating a company's tangible assets. The challenge in applying this approach to assessing brand equity is that estimating the costs a company must incur to build an identical brand is extremely complicated, especially in the case of well‐established brands that over the course of many years, and in some cases decades, have carved out a place in customer minds. Because of this limitation, the cost approach is more relevant for assessing the value of freshly minted brands for which the brand replacement costs are easier to identify—although even in this case accuracy is constrained because the cost approach might not take into account a brand's full potential to create market value.

The market approach measures brand equity as the difference between the sales revenues of a branded offering versus the sales revenues of an identical unbranded offering, adjusted for the costs of building the brand. For example, to assess the value of the Morton Salt brand, one would compare the sales revenues generated by the branded product with the sales revenues generated by its generic equivalent—regular salt—and then subtract the cost of building and managing the brand. In cases when a generic equivalent of the branded product is not readily available in the market, an alternative approach might involve using a test market to estimate the price difference between a single unit of a branded offering and (a prototype of) an identical unbranded offering, adjusted for sales volume and branding costs.

A key advantage of the market approach over the cost‐based approach is that it requires fewer assumptions in assessing the value of a brand. At the same time, the market approach has several important drawbacks that limit its validity and relevance. One of these drawbacks is that this method focuses only on one metric of brand value (the price premium) and does not consider other aspects of value created by the brand, such as more favorable terms for a branded product from a company's collaborators as well as a brand's impact on a company's ability to recruit and retain skilled employees. Furthermore, this approach assumes that the company has fully utilized the value of its brand and, hence, does not account for the value created by potential product‐line extensions, brand extensions, and licensing opportunities. The market approach also does not include the differences in the cost structure associated with branded and unbranded products because the difference in prices could also be attributed to differences in production costs rather than the price premium commanded by the brand. Another important limitation is that the market approach is not readily applicable to companies using an umbrella‐branding strategy, in which a single brand is used across different product lines in diverse product categories.

The financial approach assesses brand equity as the net present value of a brand's future earnings. This approach typically involves three key steps: estimating the company's future cash flow, estimating the contribution of the brand to this cash flow, and adjusting this cash flow using a risk factor that reflects the volatility of the earnings attributed to the brand. By considering a wider range of factors, the financial approach addresses some of the shortcomings of the cost‐based and market‐based approaches. At the same time, the financial approach is also subject to several important limitations. The first limitation is the difficulty in accurately estimating the future cash flow derived from the branded offerings. This difficulty stems, in part, from the fact that a brand's ability to generate future cash flow is contingent on a variety of extraneous factors that are difficult to predict. For example, a brand's reputation can be damaged by a product failure or a catastrophic event such as what occurred in the Tylenol poisonings, the Ford–Firestone tire recall, and the BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill.

The cash flow generated by a brand can also be influenced by a change in the market in which it operates. To illustrate, the switch to digital technology greatly reduced the size of the existing market for Kodak and Xerox, significantly diminishing the market value of these brands. Furthermore, it is difficult to separate the cash flow attributable to the brand from the cash flow attributable to nonbrand factors like production facilities, patents and know‐how, product performance, supplier and distribution networks, and management skills. Another important limitation of the financial approach is the difficulty of accurately estimating the life span of a brand, which is a prerequisite for defining the duration of the future cash flow attributable to the brand. The financial approach also does not take into account the brand value that has not been fully realized in the market, such as the value stemming from future brand extensions and licensing agreements.

The shortcomings of the different valuation methods underscore the importance of developing alternative valuation methods that employ testable assumptions and use diverse methods to measure brand value. Such approaches must take into account the strategic value of brands, including the potential for extending the brand beyond its current target markets and product categories, as well as the brand's power to influence the behavior of different market entities.

Brand Power as a Source of Market Value

Unlike brand equity, which reflects the monetary value of the brand to the company, brand power reflects the brand's ability to influence the behavior of the relevant market entities—target customers, company collaborators, and company employees. Thus, brand power reflects the difference in the ways customers, collaborators, and company employees respond to the brand. For example, if knowledge that an offering is associated with a particular brand does not change consumers’ response, the brand is lacking in power and the company's offering is effectively a commodity.

Brand power is the differential impact of brand knowledge on customers’ response to a company's marketing efforts.5 A brand has greater power when customers react more favorably to an offering because they are aware of the brand. Brand power is not always positive; for certain customers, the value of the brand might be negative, making customers less likely to purchase an offering when it is associated with a particular brand. For example, some customers display a strong loyalty to the Harley‐Davidson brand and would purchase only a Harley‐Davidson motorcycle, whereas for others the Harley‐Davidson brand might be a detractor because it conveys unfavorable associations.

Brand power is directly related to brand equity, such that the brand‐induced change in customers’ behavior generates monetary value for the company, which is reflected in the company's brand equity. The key determinant of brand power is the brand image, which reflects all beliefs, values, emotions, and behaviors customers associate with the brand. Thus, to build a powerful brand, a company must focus its activities on creating a meaningful brand image in customers’ minds that can influence their behavior in a way that creates value for the company (Figure 11.5).

In addition to influencing customer behavior, brand power benefits the company by influencing the behavior of its collaborators and employees. Thus, brand power benefits the company by increasing the likelihood that target customers will purchase the branded offering, will use it frequently, and will be more likely to endorse this offering. Greater brand power also influences collaborators’ behavior by increasing their willingness to work with the company. In addition, brand power helps the company attract a skilled workforce while enhancing employee loyalty and productivity.

Greater brand power does not automatically lead to greater brand equity. For example, the brand equity of Nissan is estimated to be higher than the brand equity of Porsche even though Porsche is a stronger brand, as reflected in its greater price premium compared to Nissan. Likewise, even though Armani and Moët & Chandon have greater brand power than Gap and McDonald's, the brand equity of the latter is estimated to be higher.6

Because brand equity is a function of brand power as well as a company's ability to utilize this power in a given market, brand equity is not always a perfect indicator of brand power. Instead, brand equity reflects the degree to which the company is able to utilize the power of the brand. Brand power, in turn, is determined by the company's strategy and tactics as well as the impact of the various market forces: customer needs; competitor and collaborator actions; and the economic, technological, sociocultural, regulatory, and physical context in which the company operates.

Given that brand power and brand equity are not perfectly correlated, it is possible to identify instances in which a brand's power exceeds its monetary value, as well as instances in which a brand's monetary valuation is overstated relative to the brand's power. A brand is undervalued when its brand equity does not account for the full market potential of the power of this brand. In contrast, a brand is overvalued when its equity overstates the underlying brand power. From a marketing perspective, brands whose brand equity is undervalued, meaning that their brand power is not fully monetized by the company, present brand‐building opportunities. From an investment perspective, undervalued brands present acquisition opportunities for companies that can unleash the hidden power of these brands.

FIGURE 11.5 Brand Power and Brand Equity

Source: Alexander Chernev, Strategic Brand Management, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: Cerebellum Press, 2020).

Conclusion

Branding is the process of endowing a company's offerings with a unique identity to differentiate them from the competition and create value above and beyond the value delivered by the other aspects of the offering. A brand's success is defined by the viability of its strategy and the effectiveness of its tactics in creating market value. The complexity of the branding decisions involved in creating market value requires that a company's brand‐building activities be guided by a clear understanding of the ways in which the brand will create value for its customers as well as the company. As companies struggle to distinguish their products and services through functional performance, they are increasingly relying on brands as a means of creating market value. In the world of rapidly commoditizing products and services, brands have become the new frontier of competitive differentiation.

Author Biography

Alexander Chernev is a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. He holds a PhD in psychology from Sofia University and a PhD in marketing from Duke University. Dr. Chernev has been ranked among the top ten most prolific scholars in the leading marketing journals and serves as an area editor and on the editorial boards of many leading research journals. He teaches marketing strategy, brand management, and behavioral science and has received numerous teaching awards, including the Top Professor Award from the Executive MBA Program, which he has received fourteen times. Dr. Chernev has written numerous textbooks on the topics of marketing strategy, brand management, and behavioral science, and has worked with Fortune 500 companies to reinvent their business models, build strong brands, and gain competitive advantage.

Notes

- 1. This chapter is largely based on the content published in Strategic Brand Management by Alexander Chernev (Chicago, IL: Cerebellum Press, 2020) and Strategic Marketing Management: Theory and Practice by Alexander Chernev (Chicago, IL: Cerebellum Press, 2019).

- 2. Phillip Nelson, “Information and Consumer Behavior,” Journal of Political Economy 78 (March–April 1970): 311–339.

- 3. Nader Tavassoli, Alina Sorescu, and Rajesh Chandy, “Employee‐Based Brand Equity: Why Firms with Strong Brands Pay Their Executives Less,” Journal of Marketing Research 51, no. 6 (2014): 676–690; C. B. Bhattacharya, Sankar Sen, and Daniel Korschun, “Using Corporate Social Responsibility to Win the War for Talent,” MIT Sloan Management Review 49 (January 2008): 37–44.

- 4. The accounting rules regarding the inclusion of brand equity on the balance sheets of a company vary across countries. Thus, in the United States, companies do not list brand equity on their balance sheets, whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia balance sheets include the value of the company's brands.

- 5. Kevin Lane Keller, Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2012).

- 6. Interbrand, Interbrand Best Global Brands (2015), www.bestglobalbrands.com