Time things right

THIS CHAPTER LOOKS AT:

- Beginning with the right activities

- Why people rush at the market, and what happens when you do

- Understanding the impact of early meetings and conversations

- How much time should you put into your job hunt

WHEN DO I BEGIN?

You might think this is a rather odd question. You might assume that if you need a job you should begin looking for it as soon as possible. Let’s look at a two very different scenarios.

Plan A – where job loss is on the horizon

Your job is coming to an end in a few months’ time – plenty of time, you might think, to line up a new job, but you’ve got a lot of work to do before you leave and you want to ensure a good hand-over to another staff member. What people typically do in this scenario is to put some energy into complaining about being laid off, and a lot of energy into maintaining their work, almost as if they half believe that the job won’t really be taken away. Any job hunt that is undertaken is often half-hearted, involving the occasional foray into job boards and applying for advertised positions. Since little effort or attention goes into job hunting, the results are low-key. These candidates get worried about the fact that their departure day is approaching, and how tough the market feels. Soon the first day comes when they are all day at home, and the phone isn’t ringing … Soon they’re talking about ‘lowering my sights’. Plan B starts to beckon.

Plan B – where you need a job fast

Here you’ve lost your job with very little notice and you need a replacement income stream quickly. Or perhaps you knew some time back that your job was coming to an end, and you’ve left it very late in the day to start job seeking.

What do people typically do? They rush into activity. They fire off a hastily-adapted CV, register with one or two agencies and job boards, and start chasing job advertisements. Great – activity. The problem is, it’s unfocused, near-random activity.

What happens when you rush at a job hunt?

- You’re not ready for questions about CV content. You haven’t rehearsed skill stories or achievement evidence.

- You’re not ready for questions about why you are currently looking for work.

- You’re unprepared for questions about the emotional impact of redundancy and bring all kinds of emotional baggage into the interview room.

- You have a weak answer to the question ‘why are you on the market right now?’

- You’re not ready for questions about your career story or where it’s going next.

- Your CV is unfocused because it’s a hastily-adapted version of one you used five years ago.

- Your CV places a huge emphasis on the job you have just left, rather than the job you’d like to get.

- You’re throwing yourself at vacancies without the first idea of what employers are looking for.

- You’re highly attuned to anything that smells vaguely like rejection. Even when it’s a good friend who fails to return a call, you may feel they have let you down hugely.

Recruiters see these half-hearted applications every week – a hurriedly patched-up CV, and an interview performance that shouts out ‘I don’t know what I have to offer or what I’m looking for, but I need a job!’. You might get an interview, but it’s far more likely that you will trip over difficult questions about your motivation to find a job.

THE REAL STORY BEHIND THE FIRST DAYS OF JOB HUNTING

Let’s slow the process down. When you leave a job, even if it’s for positive reasons, all kinds of emotions kick in. Your first Monday morning at home will probably feel very odd, especially if you’ve been in continuous work for some time. The phone isn’t ringing, no one is asking for your help or advice and your self-esteem takes a nose dive. You may feel frustrated, bored or angry with your former employer. Even the most robust candidates feel some effects, and some experience a real knock to their confidence.

Recruiters regularly see candidates who no longer believe their own CV evidence; instead, they are convinced that they have little to offer the marketplace. Worse still, they live out this belief by making compromises very early, in terms of job status or work locations which were previously out of the question. You might think this happens only to people with limited work experience, but career coaches see this vulnerability in highly experienced candidates. Self-belief is easily dented, and in a tough market there is plenty of opportunity to hear the word ‘no’, and have negative thinking thoroughly reinforced.

Career coach Jane Downes writes:

The biggest error is ‘going public’ without knowing what you want. The result is an inconsistent message being sent out to the marketplace: you can actually end up going down a route you don’t want. Candidates also often under-appreciate their transferable skills. This leads them to think of themselves in terms of deficit rather than abundant potential. Put simply, they close off very real possibilities or opportunities. The trick here is to take a full inventory of your transferable skills and then be open-minded about how these can be useful going forward.

Careers specialist Steve Preston suggests: ‘look for small wins so you always feel you are achieving something towards your goal’.

The risk, of course, is that from the first days of a job hunt you get into a downward spiral. You don’t really know what you’re doing and send out all the wrong messages so it’s inevitable that you hear negative feedback, even if it’s just ‘we don’t really understand what you’re looking for’. Does this matter? You could say that it’s inevitable that people make mistakes in the first few weeks of a job search. The problem is twofold:

- Early rejection leads to increased negative thinking.

- People remember your early job hunt performance.

Early rejection leads to increased negative thinking

Here’s something odd. You will set yourself bear traps. You will do odd back-to-front things that actually seek out negative messages. Setting yourself up to fail, just a little bit, is a great way of feeding that part of your brain which dislikes the risk of exposure and rejection. You try something difficult to prove that everything is difficult, so you can retreat into your comfort zone.

One of the tricks we use to seek out negative data is the old ‘I’m applying for this job for the practice’ game (see Chapter 17). Another is to throw yourself at a particularly high wall in week one. For example, people approach busy recruitment consultancies with an indifferent CV and a message that essentially says ‘I am not sure what I want, but please find it for me.’ Unsurprisingly, the response is usually we can’t help you or the slightly more helpful ‘come back when you’ve got your head straight’. However, your risk-avoiding brain seizes upon this as hard facts about the job market.

When people spend a lot of time explaining to their friends how difficult the job market is and how they have had to trash all their early goals, often what they are really saying is ‘I got things wrong at the outset’. If you put yourself in front of important people and then confuse them about what you’re looking for, or if you try to run before you can walk, you will certainly learn from the experience, but you will very probably also reinforce any messages that are lurking in the back of your head which are telling you how difficult things are going to be.

Getting things right often takes just a little more care and attention, particularly about who you speak to early on in the process. It’s worrying how many people mismanage phase 1 of their job hunting and then use that experience to rewrite a CV or seriously deconstruct their interview performance. As in any research activity, early data based on poor enquiry gives you very unreliable results. In a commercial research programme you adapt and improve, but for an individual conducting a job hunt this is often enough to convince you of one or both realities – there’s nothing out there, and nothing works.

People remember your early job hunt performance

Family and friends often apply pressure suggesting that the only valid strategy is to get out there as fast as possible. So you decide to play your trump cards first, and approach the people who you believe are the biggest hitters – individuals who can short cut you from A to Z – recruitment consultancies, former colleagues and bosses, your best networking contacts, perhaps a number of employers, too. You put yourself in front of these decision makers very rapidly.

What happens? The chances are you don’t get far, simply because you haven’t thought things through yet. You haven’t anticipated questions like ‘why are you on the market right now?’ or ‘why did you leave your last job?’. You will easily be tripped up by questions like ‘what exactly are you looking for?’ You use up your best opportunities in the first month – at exactly the same time you’re recovering from feeling low about unemployment. Just at that moment you’re feeling your way tentatively towards some way of pitching yourself. Ouch.

Early appearances have powerful consequences. Picture this as two separate rooms in one large office block. In one room, you’re scratching your head and wondering why a conversation didn’t go well, and feeling rather bruised by an early sense of rejection. The market seems tougher than you thought, and talking about your current situation much trickier. Imagine the person you saw yesterday in another room, busy working. This decision maker could make a big difference to your future. What does she remember about you? If your name crops up in conversation with somebody else, what will she say? Perhaps you conveyed a sense that you are bitter, unhappy, confused or simply unclear. You might get sympathy, but you probably won’t get offers or referrals. What gets remembered is that you have a problem and you are not ready to solve it yet. The message you have left in that room is not a message you want to travel in your absence.

Timing your return to the market means achieving a sensible balance between recovery and opportunity. Move too soon and you send out all the wrong messages, too late and you’ve lost energy for the task. If your experience is too raw, all people remember is your hard luck story.

Get disappointment and confusion out of your system before you put yourself in front of a decision maker. This is one of the most important tips in this book. If you’re angry about the way your past employer treated you, talk your story over with friends until you’ve got it out of your system. Avoid talking to employers while anger or bitterness might leak out.

This sounds tough, but it’s easier than some people think, because it largely requires the discipline of learning pre-prepared responses that dig you out of emotional territory quickly and shift the focus from past to present: ‘When the organisation restructured for the third time that year my role went along with dozens of others, but it’s given me a chance to think about the kind of role I really want to do. The reason I find this job attractive is …’

GETTING INTO GEAR RAPIDLY

However, don’t use reflection as an excuse to wait for ever. ‘Candidates often want a break before starting a job search,’ writes Kate Howlett. ‘If only they realised that it is normal for the search to take from four to six months – they are going to get enough time off for sure!’ Some employers find it difficult to process candidates (from first application to start date) in under four months. Kate Howlett adds:

Networking shortens and going abroad to ‘find oneself’ lengthens – the problems and questions are still there on return. I have also found that recessions shorten job search as it focuses clients’ minds, they procrastinate less, are braver and get moving faster.

You may be lucky enough to find an exciting opportunity already on your radar. If an opportunity comes up quickly, don’t make the mistake of believing that it’s too good to be true. Even if you know you could do a lot more in terms of planning and reflection, if it’s a job you want and you feel confident enough to take an interview, pursue it. Use the best CV you can prepare in a hurry, and do three things as an emergency fix:

- Match your key skills and achievements as closely as possible to the job.

- Offer three or four clear reasons in a covering letter why the employer should see you, carefully cross-referenced to the employer’s shopping list.

- Find someone to give you a practice interview which will tell you where you are in danger of failing to get a job offer.

HOW MUCH TIME SHOULD I DEDICATE TO A JOB HUNT?

Looking for a job should be your full time job is a mantra you’ll hear all too often. For most people that’s a slogan rather than a statement about reality. Let’s deal with two facts about job hunters:

- They spend less time per week job hunting than they think they do or report.

- The longer they are unemployed, the less time per week they spend job hunting.

In The Unwritten Rules of the Highly Effective Job Search, Orville Pierson recounts a survey of unemployed job seekers in the USA where two thirds reported that they spent five hours a week or less in job search. Few people spend more than 10 hours a week, even though they have just left jobs where they have worked 40, 50 or 60 hours a week.

Why do people over-estimate the time they put into job hunting? Guilt will of course always make you feel you should be doing more, so it’s reassuring to say ‘I’ve spent all week just looking for a job …’. The reality of course is that some of the time was spent fiddling around with your CV, some spent on related activities like journey planning and filing. To get results start asking yourself two questions:

- How many hours am I actually putting into job hunt?

- How much of that time is getting me any kind of result?

Agree a contract with yourself about the time you will spend on productive job hunting, and how you will record that time. Get the balance right. Career coach Kate Howlett advises her clients to undertake ‘three to four hours a day of well planned search then the rest of the day should be totally pleasurable.’

RECORDING YOUR JOB HUNTING ACTIVITY

How much time you need is of course highly variable, depending on how market ready you are when you begin. You will inevitably spend much more time at the beginning planning, reviewing and gathering information. When you are up and running you should probably aim to spend about 20 hours a week in productive activity relating to your primary goal of finding a job. That allows plenty time for travelling, family and all-important social and leisure activities – what’s the point of increasing visibility in your professional world if you cut yourself off from social contacts? However, ensure it doesn’t drain you so much that you look exhausted in meetings.

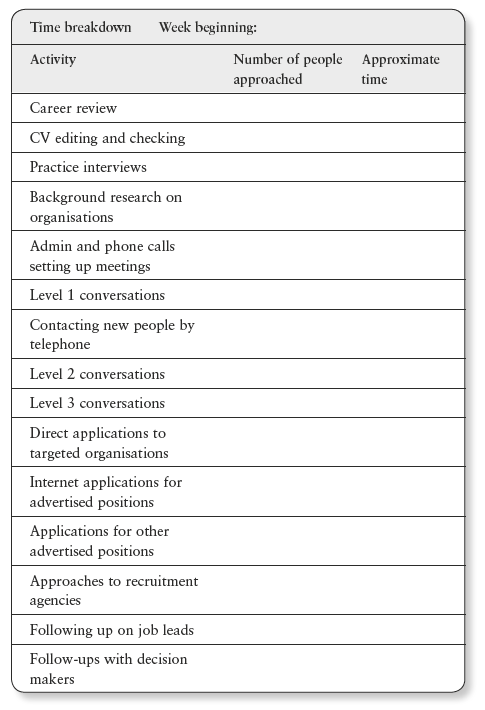

Record keeping helps you see activity and progress. The Job Hunting Timesheet below may help – particularly when you have started to understand the different stages described. Record your time approximately in terms of hours rather than minutes, but be honest with yourself. Share your activity levels with people who are supporting you through the process, and reward yourself for hitting target levels of activity. For example, you might treat yourself to a movie and a takeaway once you have contacted 15 people in a week.

Job hunting timesheet

Remember to use the Job Hunting Record Sheets (Chapter 2) to record the conversations you have and the connections you make.