Information literacy in the workplace landscape

Introduction

While there has been substantial research and advocacy for information literacy in the higher education sector, the origins lie in the workplace. The term information literacy is attributed to Zurkowski (1974, p. 178) who was concerned about the private service sector and its ability to cope with the emerging complexity of the information age. Zurkowski linked information literacy in this sector with the attainment of economic and workplace goals and the ability to solve problems around workplace tasks (Lloyd and Williamson, 2008).

Outside the educational landscape few attempts have been made to construct models or frameworks that: (1) conceptualize the practice and activities of information literacy; (2) give meaning to the experience of information literacy in other settings; (3) investigate the role and effect that the collaborative nature of workplaces has on the development of information literacy practice or outcomes; or (4) consider the implications of these issues in relation to the preparation of students for learning in the workplace. One reason for this is that the education sector has a specific focus on learning and teaching, centred on a concentrated cohort and on an information landscape that is characterized by formal learning through the systematic use of text and technologies. In contrast, workplaces and workplace interests are incredibly diverse, complex and messy. Learning about the requirements and practices of work occurs at both formal and informal levels and requires access to both explicit and tacit sources of information. Information literacy may not follow the systematic research-based process that is advocated by the higher education setting.

Locations for information literacy workplace research tend to focus around training, service and administrative sectors, where the focus is the delivery of information literacy training via the library, corporate business or service sector. Work groups in this sector have been characterized as white-collar or knowledge workers. There has been little research conducted in more applied and less information and communication technology-dependent sectors in the workplace. Additionally, to date, there is little literature that relates to information literacy as it is experienced through collaborative practice (i.e. as part of the informal learning) that occurs within the workplace.

Generally, in this sector two approaches can be identified in workplace information literacy research to date. The first approach parallels the education sector’s understandings of information literacy as a skills-based literacy, where information literacy is seen in terms of the individual achieving competence and appropriate behaviours in the development and execution of information skills. The second, more recent approach, adopts a sociological perspective that aims to theorize information literacy in a broader sense by exploring how the setting and its participants influence the development of information literacy practices and the outcomes that are produced. In this sense, information literacy is understood from a holistic perspective, where the focus is not on the individual but on the collaborative aspects of meaning making and information exchange, necessary for co-participatory work practice and the development of a shared understanding about work. Both perspectives are valid and make substantial contributions to understanding information literacy. This illustrates the idea that context matters and will affect the way in which information literacy is practised and understood by participants and those who research the area. It also suggests that while researchers will try to give meaning to information literacy as a phenomenon, practitioners will attempt to view the same phenomenon from an operational standpoint.

In early reporting of workplace information literacy, writers tended to draw from the library and/or educational literature to extrapolate a skills-based approach (Burnheim, 1992) or conceptualization (Bruce, 1996). This led to librarians in this sector advocating information literacy as a generic skills-based competency without attending to questions of transfer or context. This understanding of information literacy has begun to be questioned, particularly when viewed in the context of transfer studies and workplace learning research. These studies have produced complex understandings of how workplace learning occurs and the efficacy of transfer from one context to another. Mutch (2000) argues that information use in higher education is bounded, contextualized and directed. This use differs in comparison with the workplace ‘where their problems are messy and open-ended’ (Mutch, 2000, p. 153). In my studies I have also questioned the legitimacy of transferring educational conceptions of information literacy directly into workplace learning, which has its own unique discourses and practices (Lloyd, 2003; Lloyd-Zantiotis 2004). More recently, the question has also been raised by Boon et al. (2007), who studied academic English faculty conceptions of information in the UK. These authors suggest that it is still ‘librarians conceptions and experiences that have dominated the literature and their frameworks and models for information that have been most visible’ (p. 205).

When researching workplace information literacy the majority of researchers have focused their efforts on skills, transfer of information literacy skills from education to workplace, workplace information use, and information seeking behaviour. While the reporting of empirical research in this sector is still emerging, it has become evident that generalizations from research in the educational sector to workplace situations do not necessarily reflect the realities of experience and use of information in those contexts. Nor does the research provide a clear understanding of the outcomes of information literacy practice. This is largely due to the varied nature of work and work practices where there are differing emphases on the types of learning that occur. There are also varying views on what constitutes information and knowledge, and on what processes and practices are considered legitimate. In workplaces with tertiary-trained workforces, information literacy is often understood and will be closely connected to skills with text and information and communication technologies. In those trained in the vocational education sector, information literacy is often connected with acquiring competency or employability skills and focuses around engaging with text, people and technology. The majority of studies that have been undertaken share a common focus on the individual’s information experience, rather than on the how that experience is bounded through collective practice.

Foundation research into workplace information literacy

A number of major studies have been undertaken that explore information literacy (or information skills) in the workplace. Studies by Bruce (1996) and Cheuk (1998) focus primarily on the tertiary education sectors and tertiary-trained professionals, while a third (Lloyd-Zantiotis, 2004) focuses on the vocational and trained paraprofessional sector. It is interesting to note that while information and communication technology play a role in the first two studies, it is almost absent in this third study. This leads to questions about the importance of context in giving shape to information literacy, an issue that we will return to in a later chapter.

Bruce

Bruce’s (1997) phenomenographic doctoral research, while being reported mainly in relation to the higher education sector (see Chapter 3), drew on the experiences of effective information use among knowledge workers such as librarians and IT professionals, academics, and staff in the higher education workplace. The outcomes of this published research known as the Seven Faces of Information Literacy identified seven different ways of experiencing information, which Bruce then extrapolated into the experience of information literacy in an educational workplace. According to Bruce (1999, p. 35), knowledge workers experienced information literacy in their workplaces as:

![]() varying emphases on technology;

varying emphases on technology;

![]() emphasis on the capacity to engage in broad professional responsibilities, rather than specific skills;

emphasis on the capacity to engage in broad professional responsibilities, rather than specific skills;

![]() social collaboration or interdependence between colleagues, rather than an emphasis on individual capability;

social collaboration or interdependence between colleagues, rather than an emphasis on individual capability;

![]() need for the partnership of information intermediaries; and

need for the partnership of information intermediaries; and

![]() emphasis on intellectual manipulation of information rather than technical skill with IT.

emphasis on intellectual manipulation of information rather than technical skill with IT.

Bruce’s (1999, p. 46) conception of information literacy focuses on ‘peoples’ ability to operate effectively in an information society’. This author suggests that learning organizations should require their employees to possess a suite of information-based abilities in order to operate effectively. She lists this suite as: critical thinking, the ability to identify an information need, awareness of personal and professional ethics, and, the ability to evaluate and organize information and to use information effectively in problem solving. Bruce (1999) suggests these experiences should influence how information literacy is taught in professional education programmes. She warns against decontextualizing information literacy skills, arguing that they will have a ‘short shelf life’ and will fail the individual in the workplace unless they are learned in the context of workplace competencies and expectations.

Cheuk

The picture of workplace information use developed by Cheuk (1998) focused specifically on an activity of information literacy within a professional context, i.e. the information seeking and use processes of auditors. Working from a user-centred perspective, Cheuk (1998) identified that the information seeking process was largely individualistic and often unpredictable. The outcome of this research was a two-stage model described by Cheuk as information consumption and information supply. Cheuk’s research contrasts with the systemic and prescriptive skills-based approach identified in the library literature, in that it illustrates that the information-seeking process and experience within the workplace may be viewed as an unstructured, cyclical and repetitive process of information seeking. In this research Cheuk claims a constructivist perspective, and employs a qualitative method of sense making derived from Dervin (1992) to develop a model of information literacy for internal auditors.

Cheuk (2000, p. 178) defined information literacy as ‘going through an information seeking and use process to acquire new meaning and understanding’. This definition was extended by her for workplace contexts as ‘a set of abilities for employees to recognize when information is needed and to locate, evaluate, organize and use information effectively, as well as the abilities to create, package and present information effectively to the intended audience’ (Cheuk, 2002, intro, para 1). Cheuk’s research has illustrated common information-seeking and use processes within the workplace that share similarities with educational conceptions of information literacy as a skills-based literacy. These include the need to plan the processes of seeking information, gathering of information (information consumption) and presentation of information (information supply). This study emphasized the diverse activities that characterize information seeking, and use processes in the ‘real life practice in handling information at work’ (2000, p. 183). These were described by Cheuk (2000, pp. 183–184) as follows:

![]() information seeking is not always necessary;

information seeking is not always necessary;

![]() information seeking is by trial and error;

information seeking is by trial and error;

![]() getting information is not equal to getting the answer;

getting information is not equal to getting the answer;

![]() information seeking is not linear;

information seeking is not linear;

Cheuk’s research also raises questions relating to whether alternative models of information literacy are required for the workplace. In particular, the assertion that information seeking is not always necessary, nor is it an individual activity, has been supported in other recent studies (Lloyd-Zantiotis, 2004; Hepworth and Smith, 2008). This view appears contrary to the understanding that prevails in the higher education sector that to be information literate a person must recognize that they need information and have developed the ability to find information.

While Bruce and Cheuk focused their research efforts on knowledge workers or workers employed in the higher education sector, I have shifted away from these sectors and grounded my research in vocational and paraprofessional settings. My work explores the nature and manifestation of information literacy as a collaborative practice in settings where the focus is primarily on informal learning related to the performance and practice of work.

Lloyd

My doctoral research (Lloyd-Zantiotis, 2004) and more recent work within the emergency services sector (Lloyd, 2007), has focused on workers who could not be classified as knowledge workers. The results from my study reveal another side to information literacy as a socio-cultural practice, one that informs learning about workplace practice and is in turn informed by it. A practice where the activity of sharing and interpreting information is just as important as the activities that enable access (Lloyd-Zantiotis, 2004). Drawing from socio-cultural and workplace learning theory, I recognize information literacy as a holistic practice, one where the focus is not on the individual’s experience of information but on the individual’s experience of information in consort with others. In fact, the way in which information literacy emerges as practice will be influenced by the discourse of the setting, which sanctions and legitimizes information modalities and information-related activities. Information literacy produces a way of knowing about the practices and processes that inform learning about context. This will be explored in more detail later in this chapter.

While the three large studies by Bruce, Cheuk and my own, briefly described above, have been influential in the illustration of information literacy in the workplace, other smaller studies have also been conducted that focus on the individual developing skills to use information. This view is similar to the prevailing education view of information literacy as a skills-based literacy or competency, one that is generic and transferable from one context to another.

Information literacy as a competency and skill

When first conceived by Zurkowski (1974), information literacy was associated with the ability to develop techniques and skills in the use of information tools that would assist with problem solving (Lloyd-Zantiotis, 2004). Zurkowski (1974, p. 6) stated that: ‘People trained in the application of information sources to their work can be called information literate. They have learned techniques and skills for utilizing the wide range of information tools as well as primary sources in moulding information solutions to their problems.’

At the time of this description, the information age was dawning and Zurkowski recognized that computers would become an important feature of service work. Information literacy was viewed in functional terms, reflecting the functional view of reading and writing that prevailed in the 1970s. Zurkowski argued that those workers who were information literate, i.e. who had the ability to apply the techniques and skills and to interpret information to solve workplace problems would provide the competitive edge for business.

Parenthetically, the terms skill and competency are often used interchangeably in the library literature but they are in reality not the same things. A skill refers to a combination of abilities that are underpinned by specific knowledge and to ‘a person’s mental, manual, motor, perceptual or social abilities’ (Tovey, 1997, p. 12). The standard at which the skill or task is performed can then be measured against an agreed set of performance or skill indicators (Tovey, 1997, p. 13). A competency is more than just a skill, it also addresses ‘knowledge, skills and attitudes required of the individual to perform the job at the level required’ (Tovey, 1997, p. 12). There are three aspects to competency (Tovey, 1997, p. 13), which:

![]() will include measurement against an independently agreed set of criteria;

will include measurement against an independently agreed set of criteria;

When information literacy is perceived as a competency with information, the focus turns towards the ability to create and apply a set of criteria that outlines a suite of skills, which can then be measured against performance. Information skills have been associated with those skills required to find, retrieve, analyse and use information. They are, in general, categorized as task definition skills, information seeking strategies, searching skills, the ability to synthesize and evaluate information (Webb and Powis, 2004).

This is best illustrated through the various standards for information literacy, which were described in the previous chapter (e.g. ACRL, ANZIIL, and SCONUL). However, it could be argued that this approach to understanding information literacy reflects a librarian’s perspective of information literacy, which in many cases is focused on the context of education and individual learning rather than the context of work and the realities of collaborative workplace practice.

In Australia, information literacy was embraced in the vocational training sector by librarians who: (1) advocated for the development of skill and competency aspects of information literacy; (2) understood the empowering role of information literacy in building effective and efficient workplaces; and (3) saw information literacy education as a way of ensuring their relevance in this ever changing sector. However, a failure to clearly articulate the role of information literacy in relation to its contribution to workplace learning meant that the phenomenon received little attention by TAFE (Technical and Further Education) educators. While there was an initial flurry of activity around the promotion of information literacy in the 1980s and 1990s, this seems to have died down in the early years of the twenty-first century.

The idea that information skills are essential to workplace productivity has long been visible in the vocational education sector in Australia. While information literacy is not specifically mentioned, information competencies have been included in a range of reforms (e.g. reports by Finn, 1991; Mayer, 1992). Both reports emphasized the importance of students in this sector developing the capacity to collect, sift, and sort and analyse information. In the 1990s, Burnheim (1992) writing from this setting, advocated and described information literacy as a separate core competency, underpinned by a constellation of information-related skills, which enabled the individual to think critically about information. Burnheim connected information literacy with economic goals such as workplace efficiency and an ability to quickly adapt to change. A key characteristic of an information literate person according to this author was the ability to encompass change through the development of transferable skills. In this context, Burnheim also connected workplace information literacy to the lifelong learning agenda that was at the time emerging in the broader education sector. While arguing for information literacy as a core competency Burnheim (1992, p. 194) identified a list of goals that students who were studying through the vocational education sector should reach, which included:

![]() an awareness of the range of information resources available through a wide variety of information providers;

an awareness of the range of information resources available through a wide variety of information providers;

![]() a sound grounding in research process methods;

a sound grounding in research process methods;

![]() a sound knowledge of how information and information resources are organized; and,

a sound knowledge of how information and information resources are organized; and,

![]() students being confident, competent users of information resources.

students being confident, competent users of information resources.

A list of competencies were then described that needed to be mastered by students in order to achieve these goals. Burnheim suggested that these competencies need to be the core across all subjects rather than subject specific, highlighting his understanding of information literacy as a generic competency. These competencies were listed (p. 194) as the ability to:

![]() formulate and analyse the information need;

formulate and analyse the information need;

![]() identify and appraise the worth of likely sources;

identify and appraise the worth of likely sources;

![]() trace and locate individual resources;

trace and locate individual resources;

![]() examine, select and reject individual resources in the light of the information need;

examine, select and reject individual resources in the light of the information need;

![]() interrogate resources to isolate required information;

interrogate resources to isolate required information;

![]() interpret, analyse, synthesize and evaluate the information gathered;

interpret, analyse, synthesize and evaluate the information gathered;

This understanding of information literacy was influenced by the earlier work that had been undertaken in the educational sector (e.g. Breivik, 1985) and was formed around an understanding of information as objective, discoverable and reproducible. In this view of information literacy emphasis was placed on the individual achieving a mastery of information and the skills required to access it.

The idea of information literacy as a core competency for workers, and one that is critical to building and maintaining organizational capacity, has been explored in Australia by Gasteen and O’Sullivan (2000) who connect information literacy to an organization’s capacity to build and maintain knowledge. In their study of a legal firm, the development of information literacy is viewed as central to a lawyer’s skills and a requirement of the workplace as a learning organization. Based on their study, Gasteen and O’Sullivan connect information literacy to the attainment, through training, of information skills such as the ability to define, locate, evaluate, manage and organize information. In addition to skills training, these authors suggest that to support employees in their work, librarians must develop the ability to scaffold their understanding of information literacy to concepts used in the workplace, to ensure that information literacy training is relevant. The authors (Gasteen and O’Sullivan, 2002, p. 13) suggest that: ‘We must broaden our outlook, see ourselves as part of the business and pursue interests that are relevant to it. It involves changing the way we envisage our role. In a knowledge based world, no one can afford to live in an ivory tower’.

The authors conclude that librarians need to understand their practice in relation to information literacy in the workplace and consider adapting and embracing the language of the business world, aligning information literacy as an information or knowledge economy concept.

Smith and Martina (2004) advocate that information literacy is equally important in the vocational education sector; however, they note the assumption of their tertiary education counterparts, that there is not as much urgency in embedding information literacy into the vocational educational curriculum as most students are learning a trade. This reinforces Stevenson’s (2002, p. 2) argument that historically, vocational and workplace knowledge has traditionally been relegated to ‘second best’ because it is primarily believed to be concerned with the ‘material, the technical, and the routine’. In a small study, undertaken from a library-centric and skills-based perspective, Smith and Martina (2004), explored the baking industry in Australia, and focused their examination on the relationship between information literacy and ‘employability’ skills (previously known in Australia as key competencies), which described generic skills required by all employees. They (p. 329) concluded that:

It is not enough to show students how to use a particular library or where to find the books they need. By definition, if the skill is taught and understood then it becomes an employable skill. Students will then be able to relate finding information to their everyday working environment and to their adult life in general.

In a snapshot of information literacy practices by TAFE librarians in Victoria, Australia, Fafeita (2005) identified a raft of issues that impact on the effective implementation of information literacy programmes. Issues that are familiar to librarians in higher education sector (Fafeita, 2005, p. 106), included:

![]() a lack of consensus about the term information literacy;

a lack of consensus about the term information literacy;

![]() a narrow conception of the practice that focuses on skills;

a narrow conception of the practice that focuses on skills;

![]() the operational boundaries in which TAFE librarians are required to work, time constraints within the already packed vocational curriculum, which limits opportunities to effectively embed information literacy practice;

the operational boundaries in which TAFE librarians are required to work, time constraints within the already packed vocational curriculum, which limits opportunities to effectively embed information literacy practice;

![]() lack of resources to support the development of information literacy programmes;

lack of resources to support the development of information literacy programmes;

![]() users’ attitudes towards learning about information literacy skills until the point when they need it;

users’ attitudes towards learning about information literacy skills until the point when they need it;

![]() the barriers presented with language and PC skills of clients; and

the barriers presented with language and PC skills of clients; and

![]() teachers’ failure to understand the information literacy concept and how it could benefit students were also identified a barrier.

teachers’ failure to understand the information literacy concept and how it could benefit students were also identified a barrier.

Many of the barriers point to the lack of research in the vocational education sector resulting in a failure to adequately conceptualize and articulate information literacy for practitioners and educators within this sector. The long-term impact is becoming increasingly evident in the literature that focuses on information literacy skill development and work ready employees.

Corporate and small business sectors

Rosenberg (2002) in the USA has explored the importance of information literacy as a necessary skill in the operation of small businesses, particularly in the global networked world. Rosenberg emphasized that employees in small business are often under-equipped in key information skills such as the ability to evaluate information found on the Internet. He argued that small business employees ‘must understand the value of information and must be able to acquire and use information’ (p. 8) and that this will require employees who have developed sophisticated information literacy practice. Rosenberg (2002, p. 10) states that:

Successful business people have long known that having certain types of information conveys a significant strategic advantage to a company. Also new is the importance of information literacy in the new global marketplace. Information literacy was always important to businesses, but now it takes on a new importance because of the changes wrought by the new network technologies. When businesses are connected to each other, information becomes especially valuable.

The lack of information literacy skills of employees in SMEs (small to medium businesses), particularly web-based information, is evidenced in De Saulles (2007) who argues that UK government policy intervention is needed to optimize their major investment in information and communication technology infrastructure. Major policy and investment in information literacy training is needed to make SME employees information literate in business information. He argues that the cost of time wasting and inefficient information searching on the web, to UK SMEs, reached somewhere in the vicinity of £3.7–8.2 billion per year.

While De Saulles (2007) discusses SMEs, a report by Kielstra for the Economist Intelligence Unit on company decision making, expresses concern that executives and workers do not have the information to make critical business decisions. In this worldwide online survey and follow-up in-depth interviews of 154 business executives, a number of issues were identified that run to the core of the information literacy agenda. These highlight the need for stronger advocacy for the development of information literacy practice and skills in the workplace as one expert stated in this study ‘you cannot make proper decisions without proper information’ (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2007, p. 2). The results of this study indicate that there is concern among executives that in highly competitive markets the lack of information or poor information leads to poor decisions. In this respect there is recognition that information not only relates to codified knowledge (e.g. as financial data) but is also important when it relates to competitor knowledge, market environments and the company itself. The report also highlights the importance of collaborative practices, and it indicates that while technology helps to a point (p. 7) executives also value the importance of other people as a strategic information source as most decisions were made on an ad hoc or informal basis. While not discussed by the authors, this response alludes to the need to trust the information of other people and suggests that collaborative networks play an important part in decision making. The report by Kielstra (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2007, p. 14) concludes with two broad areas for future focus: ‘The first is in obtaining, filtering and verifying the necessary data need for decision makers. This is where technology comes into play … The other is to understand how human beings fit into the process.’

Understanding the strategic value of information literacy in the decision making cycle has been absent from the current research suite of studies into workplace information literacy. This area represents an important area for future study, which may then promote the importance of information literacy practice.

Adding to the weight of evidence that points to the costs involved in not having an information literate workforce, Breivik (2005) notes that, Don Cohen a Ford Motor Company executive describes that cost in terms of time: ‘The costs of information illiteracy are high … We typically can only find half of the information we need to do our jobs and spend up to 30 percent of our time looking for the other half’ (Cohen 1998, p. 21 cited in Breivik 2005, p. 23). The cost is also recognized in the US Department of the Navy, where it is estimated that that average worker ‘spends an estimated 150 hours per year looking for information’ (Bennett, 2001, p. 1 cited in Breivik, 2005, p. 23). Breivik notes that the loss of time and productivity described by these authors could be greatly reduced by an information literate workforce (Breivik, 2005, p. 23).

The idea that good information literacy practice is expected by employers, although this expectation is assumed rather than made explicit, has been explored in Scotland by Irving and Crawford (2008). These authors advocate the need to develop an overarching framework of information literacy competencies and skills that can be recognized and understood in the education sector and can then be applied to the workplace. In advocating for a National Information Literacy Framework for Scotland, Irving and Crawford (2008, p. 7) draw from the SCONUL Seven Pillars Model developed for higher education in the UK. The framework involves several skills and competencies defined by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP group) as requiring the individual to develop an understanding of:

![]() how to work with or exploit results;

how to work with or exploit results;

![]() ethics and responsibility of use;

ethics and responsibility of use;

A more recent study by these authors on the use of information in the workplace and its role in decision making stated among its conclusions that, in Scottish workplaces (Crawford and Irving, 2009, p. 9),

![]() people must be recognized as a legitimate source of workplace information;

people must be recognized as a legitimate source of workplace information;

![]() information literacy must be highly targeted;

information literacy must be highly targeted;

![]() skills audits are required before designing information literacy training programmes;

skills audits are required before designing information literacy training programmes;

![]() there is widespread understanding of what constitutes information literacy, but this understanding is implicit rather than explicit.

there is widespread understanding of what constitutes information literacy, but this understanding is implicit rather than explicit.

Advocating information literacy skills into the workplace

While there is significant attention paid to developing information literacy and its value to students in the education sector, the question of how information literacy can be made explicit and implemented into formal workplace training has received little attention in the literature. This represents a gap that requires serious attention from researchers and practitioners.

Attempting to implement information literacy strategies into the workplace can be facilitated, in the view of Oman (2001) by taking an organization-wide implementation approach. This author suggests that when presenting the case to management, demonstrating the value of information literacy to the company is a key argument followed up with ‘tactical solutions’ for implementation. She argues that:

Placing your initiative in the silo of your group will not work. Success is more likely when you tie information literacy to internal employee development and compensation plans. The reality is, the ‘what’s in it for me’ factor is a much stronger incentive than any other benefit your group can describe. This needs to be explained to management, potential internal partners, and individual employees (para 20).

Oman also suggests that a further opportunity for information literacy development in an organization might reside in demonstrating the links between information literacy and knowledge management. This is a view shared by Cheuk (2002) and O’Sullivan (2002). Other opportunities identified by Oman (2001) and O’Sullivan (2002) were partnering with human resources to identify information literacy competencies and training needs, and the mapping of information literacy skills against business processes.

The notion that information literacy must be promoted in the workplace has been considered by a number of authors. In her report to UNESCO on information literacy in the corporate workplace, Cheuk (2002, p. 5) suggests that people are ‘drowning in the sea of information’ because they are not equipped with the necessary information literacy skills; a concern originally expressed by Zurkowski in 1974. At the same time, Cheuk reports that workplaces provide limited opportunities for information literacy training to occur because of the lack of awareness about information literacy in work settings (2002, p. 5). Cheuk recognizes a number of barriers that affect the promotion of information literacy in workplace settings. She lists these (p. 10) as the:

![]() lack of familiarity with the terminology related to the concept of information literacy;

lack of familiarity with the terminology related to the concept of information literacy;

![]() differing mindsets between the workplace and education settings, in particular, a change in corporate culture towards valuing innovative thinking and problem solving; and

differing mindsets between the workplace and education settings, in particular, a change in corporate culture towards valuing innovative thinking and problem solving; and

![]() the expectation that employees come to the workplace with information literacy skills already established, which results in these skills not being promoted in the workplace.

the expectation that employees come to the workplace with information literacy skills already established, which results in these skills not being promoted in the workplace.

Cheuk (2002, p. 9) identified a number of factors that could be used to promote information in the workplace. These are:

![]() training on optimizing new technologies that manage information;

training on optimizing new technologies that manage information;

![]() including information literacy into the curriculum of continuous education and training schemes;

including information literacy into the curriculum of continuous education and training schemes;

![]() increasing employee awareness about the fact that they are knowledge workers that access and use information in their day to day work;

increasing employee awareness about the fact that they are knowledge workers that access and use information in their day to day work;

![]() recognizing information literacy as a critical business skill and equally as important as communication or presentation skills; and

recognizing information literacy as a critical business skill and equally as important as communication or presentation skills; and

![]() recognizing the achievements of employees who create quality information.

recognizing the achievements of employees who create quality information.

Barriers to effective promotion and advocacy of information literacy in the workplace have been recognized by a number of authors. These activities rest on the ability of librarians and researchers to translate and articulate the concept of information literacy in ways that can be understood by employers (O’Sullivan 2002; Hepworth and Smith 2008). While specifically addressing this issue in relation to corporate business O’Sullivan’s (2002) words resonate as relevant to all workplace sectors when she suggest that: ‘Language and communication is part of the problem as demonstrated by the exercise of searching for library jargon in business literature. Because library terminology is foreign to corporate managers, the first step is to apply corporate terminology to relevant information concepts … So we must search for new ways of describing information literacy and align it with business concepts’ (p. 13).

The predominant workplace information literacy themes in the literature reveal that for this sector there is a prevailing behaviourist/cognitivist view of information literacy, related to the individual attainment of information skills and attributes. These are largely focused around text and technology and uncoupled to the realities of workplace practice and performance. However, other views of information literacy are also emerging from this sector. Drawing largely from socio-cultural theory, which considers the information experience in a broader sense as related to developing intersubjective positions, which enable the development of workplace identity and co-participatory work practice. In this view, the focus is more holistic and considers the information relationships between people in situ, the importance of information sharing as a collaborative practice and the influence of discourse in shaping the information practices of the workplace.

Beyond skills

Moving beyond the information skills needed in the post-Fordist workplace, Kapitzke (2003) believes that information literacy as it is taught in classrooms needs to better prepare students with attributes necessary for the transitory nature of the global workplace. Here workers are required to be adaptable and flexible and to understand how knowledge is constructed, contested and socially distributed across networked workplaces. She suggests that:

Industry today focuses on speed, flexibility, and innovation; expertise is viewed not as a product but as a fluid process. Knowledge is developed within globally spread communities of practice that are embodied in organizational, intellectual, social, cultural and material interactions among members with a range of tools and technologies. New workplaces have a greater need for people who are good at collaborating and sharing knowledge than for smart individuals who, when they leave the enterprise, take their skills and expertise with them (p. 48).

Hepworth and Smith (2008) compared the information literacy needs of non-academic staff employed in higher education with the JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) i-skills model. The model identifies a number of elements in the information cycle (i.e. information need, assessment of need, information retrieval, critical evaluation, adaptation of information, organization communication and review of information) (p. 214). In discussing their findings, the authors noted that the workplace model of i-skills is ‘very different from that in the academic context’ (p. 226). Where ‘common conceptions of information literacy describe the process a researcher or student follows in completing an individual task or assignment’ (p. 226). They argue that ‘ … i-skills, stemming from the academic context, rather than being a generic phenomena commonly understood by all, may be context specific and people’s experience of information literacy may not echo LIS conceptions of information literacy’ (p. 226). This statement supports my workplace research (2005a,b, 2006a,b) that argued that information literacy practice will manifest differently according to the context in which it is practised. I have also suggested that the standards and guidelines for information literacy that have been developed in educational contexts may not be appropriate for describing and understanding the information literacy practice in other settings (Lloyd, 2003).

In their study, Hepworth and Smith (2008) identified that employees often do not have to identify an information need, partly because managers assigned well-defined tasks. Interestingly, in my (2004, 2007) studies of emergency services workers it was also noted that the need to identify a topic or the identification of an information need was not recognized by novices. This was because tasks and the required information were provided by more experienced officers, who identified the need through observation of novice practice.

Hepworth and Smith also noted in their study that the information experience was collaborative and was manifest through teamwork rather than focused on individuals, pointing to social dimensions of the information literacy experience being important, a point I also raised in 2005. Hepworth and Smith (2008, p. 227) suggest that ‘If librarians and information professionals wish to support information literacy in the work context, they need to take on board a wider conception of the information landscape and information management in the workplace. Plus they need to appreciate the socially embedded nature of information literacy’.

In their exploration of this cycle, Hepworth and Smith (2008) identified other skills not evident in the JISC cycle that had a ‘significant bearing on staff management of information’ (p. 220). These skills were related to issues (pp. 222–223), such as:

![]() time management and information overload, which require judgement skills;

time management and information overload, which require judgement skills;

![]() the need for social networking skills (internal and external to the institution) including; ‘the ability to identify and connect with other people; and, ask precise and accurate questions in order to elicit the required information were significant and necessary skills’.

the need for social networking skills (internal and external to the institution) including; ‘the ability to identify and connect with other people; and, ask precise and accurate questions in order to elicit the required information were significant and necessary skills’.

![]() listening and having the ability to sift through information and make judgements about relevancy were also considered important; and

listening and having the ability to sift through information and make judgements about relevancy were also considered important; and

![]() development of team-working skills, primarily because information expertise and skill is normally spread across a team rather than just located.

development of team-working skills, primarily because information expertise and skill is normally spread across a team rather than just located.

Information literacy from a socio-cultural perspective: Lloyd’s workplace studies

In this next section two studies of workplace information literacy practice are described. My interest in workplace information literacy is to understand how information literacy is used as a socio-cultural practice in order to establish participants in the practice and performances of the workplace. The focus of these discourse-oriented studies was to understand the nature of information literacy and identify how it enables access to the social, cultural, material and technical ways of knowing the workplace landscape, in particular, how information literacy:

![]() manifests in the process of learning about sociality of the workplace as an intersubjective space; and

manifests in the process of learning about sociality of the workplace as an intersubjective space; and

![]() enables the development of practical understandings about the performance of work.

enables the development of practical understandings about the performance of work.

In both studies, information literacy was identified as a holistic and situated experience, which I reconceptualized (2007) as a complex socio-cultural practice. This places emphasis not only on the information produced, but also on the way information is understood, interpreted, shared and sanctioned by members who are engaged in collective practice. In this way information literacy becomes a critical catalyst in the construction of meaningful frameworks about workplace practice, regardless of what that practice is.

Through my research (2003, 2005a,b 2006b) I have reconceptualized information literacy as a practice that facilitates a ‘way of knowing’ about the sources of information that will inform performance and participation. These information sources are not confined to textual sources but are also social and physical sources that constitute an information landscape, producing an information experience that has embodied and social dimensions in addition to the cognitive. Consequently, I understand information literacy as being holistic.

Exploring information literacy outside traditional classroom and library contexts, I understand workplace information literacy from a constructionist perspective, as a complex, messy and collaborative. By engaging in this practice, the member comes to know the information environment, in particular, the information modalities that are sanctioned as legitimate sources of knowledge and the information activities related to the specific setting in which they work.

My interest in information literacy lies in developing an understanding of how the whole body engages with an information landscape. I question whether the experience of information literacy in educational contexts (and the behaviours and skills learnt there) can effectively transfer from educational environments to workplaces given there are differing discourses (e.g. histories, assumptions, values and ways of relating) that influence what information and knowledge are authorized and the ways of participation that are encouraged. My contribution to information literacy lies in the richer understanding of the modalities of information within a landscape, in particular, the role that social and corporeal (body) modalities play as sources of information.

Based on my research information literacy is:

![]() an intersubjective accomplishment because workplaces emphasize the importance of teamwork and collaboration:

an intersubjective accomplishment because workplaces emphasize the importance of teamwork and collaboration:

– this requires workplace participants to develop a shared view of practice and profession and a shared understanding of information;

– it necessitates engaging with information that is valued by the community of workers;

![]() dependent upon the opportunities (affordances) offered to newcomers by experienced practitioners within the community of practice;

dependent upon the opportunities (affordances) offered to newcomers by experienced practitioners within the community of practice;

![]() a transformative process, in which the new worker’s engagement with information facilitates over time the transition of workplace identity from novice to experienced worker;

a transformative process, in which the new worker’s engagement with information facilitates over time the transition of workplace identity from novice to experienced worker;

![]() a constellation of social, physical and textual practices, which enables knowing about work practice and facilitates the development of a workplace identity;

a constellation of social, physical and textual practices, which enables knowing about work practice and facilitates the development of a workplace identity;

![]() a connector to learning about workplace practice and profession by facilitating the engagement between information sites that relate to conceptual knowledge and information sites that relate to embodied knowing.

a connector to learning about workplace practice and profession by facilitating the engagement between information sites that relate to conceptual knowledge and information sites that relate to embodied knowing.

In addition I view information literacy as:

![]() situational and driven by the need to access information contained within the symbols and artefacts and obtained through interactions; these are central and significant to the shared understanding, meaning and expression of identity, practice and profession; and

situational and driven by the need to access information contained within the symbols and artefacts and obtained through interactions; these are central and significant to the shared understanding, meaning and expression of identity, practice and profession; and

![]() a problematic and often highly contested practice, because information landscapes are socially, politically and historically constituted and this influence shapes information and the type of knowledge and information behaviours and activities that are valued.

a problematic and often highly contested practice, because information landscapes are socially, politically and historically constituted and this influence shapes information and the type of knowledge and information behaviours and activities that are valued.

Two themes emerge from Lloyd’s work

Two major themes emerged from the emergency service studies. These themes reveal the similarities of experience and use of information in the workplaces of frontline emergency services practitioners and the power of information literacy to act as a transformative practice. In the first theme, learning to act as practitioner, outcomes of an experience with codified sources of information (e.g. text) are illustrated. The second theme learning to become a practitioner illustrates how the changing experience with information occurs when the novice moves away from the context-independent safety of the training context and towards contextual engagement with the workplace community and the information modalities and information activities it sanctions.

Learning to act as a practitioner

In their preparatory training both fire fighting and ambulance novices must undertake formalized competency-based training, which is assessable against the specific standards of each of the employing service organizations. In this early stage of workplace learning, the information environment of novices is deliberative and protective (Flyvbjerg, 2001) and is removed from the realities and uncertainties of actual workplace practice. The context independent nature of this preparatory environment centres on codified sources of information with a focus on individual attainment of skills and competency. Information in this environment is abstract, generalizable and can be reproduced and restated and is, therefore, assessable. Novices learn to recognize factual information and adopt information behaviours that are relevant for the acquisition of skills and competencies they are required to pass. However, because preparatory training occurs away from the workplace, in training centres or vocational colleges, this recognition and experience of information occurs without reference to concrete situations. Novices engage with this organizationally provided information in order to learn the rules, regulations, procedures and sanctioned practices of their service organization. Performance is evaluated against the existing statements described by rules, regulations, training manuals, policy and technical documents and competency-based assessments. The outcome of this engagement is the development of a subjective workplace identity, which can be recognized by the organization and by other practitioners and places novices on the periphery of the community of practice (Wenger, 1998).

Connecting with this type of information assists the newcomer with the construction of individual subjectivity, a sense of self and an understanding of their relationship to the formal organization and its agreed practices of work (Weedon, 1997). By engaging with information from these sources, newcomers are also positioned in relation to the power structures within the institutional discourse. In effect, engaging with codified sources of information allows the novice to become an effect or product of the discourse and is recognized by the workplace community (Morris and Beckett, 2004).

By engaging with institutional modalities of information, novices learn to act as practitioners, and develop the ‘know-why’ of knowledge (Billett, 2001, p. 85) but they cannot become practitioners because they are removed from the reflexive and reflective embodied experiences and tensions arising from practice. They are also removed from connecting with the community of workplace practitioners whose nuanced understanding of work performance is embedded within the social narratives of practice. In preparatory training, corporeal information prepares the novice’s body for routine work through the rehearsal of procedural practice, but cannot prepare the novice body for the actual performance of real work because it is removed from the uncertainties of actual practice.

Similarly, while in training there is limited engagement with social modalities of information that will produce the level of intersubjectivity crucial for learning team performance and engaging with the shared sense of meaning, which is fundamental to the development of a professionally recognized identity. In the preparatory stages, social connections are made with trainers and educators whose primary role is to afford opportunities for novices to engage with the workplace-training environment. Trainers mediate and influence the novice’s information engagement towards the epistemic understandings of practice that will produce successful assessable outcomes. However, once novices are assigned to workplaces, these understandings are often contested, because they may not reflect the nuanced or embodied workplace understanding, which is gained through actual work and engagement with members of the community.

This preparatory stage is important for novices because the modalities of information that are engaged with in the training centre, although abstract, allows them to develop a workplace identity that is recognizable, in organizational terms, and brings them to the periphery of actual practice. However, it is not until they engage with the community that they begin the process of developing a full workplace identity and can become an information literate worker.

Becoming a practitioner

On being assigned to their stations, novices commence the process of engaging with information from an altered discourse, one that reflects the collective perceptions of practice, profession and competency, cultural values and group history. This discourse is collective and has been constructed and agreed upon through access to everyday experiential and social information. Experienced practitioners expressed the importance of social and physical information experiences as critical in providing information that is central to the development of their performance and understandings of professional practice. One study has argued (Lloyd and Somerville, 2006) that as an intersubjective experience, workplace learning must include recognition of the body as a central information source, which facilities reflection and reflexivity. In addition the socio-cultural practices of the workplace are also recognized by practitioners as critical information sources that connect workers through shared experiences and render shared understandings about place and practice.

The acquisition of this type of information is largely informal, acquired through participation or communication between members and constituted through the development of social relations that underpin teamwork. For novices and experienced officers the value of social information lies in its application and use. By engaging with the conversations of collective practice, novices are able to move towards developing an intersubjective understanding of information that facilitates a collective view of work and of workplace practice. Learning about this source of information and how to access, interrogate and evaluate it is largely ‘invisible work’ and enables learning to occur ‘on the job rather than off the job’ (Eraut, 2004, p. 249).

Becoming a practitioner is not only achieved through the acquisition of codified or social information. It also requires the coupling of these forms of information with physical information. Coupling is central to the transition from novice to experienced practitioner. It is the process whereby information accessed from textual sites, from social sites and from the physical experience of authentic practice is drawn together, rendering the recruit in place. Therefore, physical information is central to becoming information literate in this workplace.

Physical information is central to the developing relationships between novices and experts. As a source of information, bodies provide their novice owners with a collection point for sensory information gained through actual experience. Importantly, bodies provide a narrative of this experience or lack of experience for others to see; therefore, they become an important source of information for others as well. Experienced workers observe novice bodies for information gaps and then use their own bodies to fill those gaps in, by demonstrating the missing information.

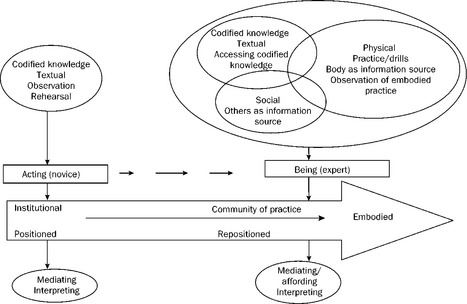

Practitioners, through their experience, recognize that the textual site is important for developing a preparatory framework for practice. However, once engaged with actual practice, these sites are deemed less important and can become contestable against the information experiences of embodied performance and the development of real workplace relationships. The relationship between people in the information literacy process is illustrated in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Illustrates workplace information literacy for the groups studied. Adapted from Lloyd-Zantiotis (2004)

In the preparatory stage of training, the information environment is driven by codified sources of information in which the rules, regulations, policies and procedures for practice are outlined for the novice by the institution. Engaging with epistemic knowledge allows the novice to be positioned by the institution through the formation of institutional identity. Information practice is mediated by experienced trainers who guide the novice to appropriate sources of information that enable them to pass the competency-based training requirements. As part of the mediating role, information is also interpreted by experienced trainers on behalf of novices who, because of their lack of experience, are yet to contextualize their practice. In the transition to the workplace, novices engage with an environment that has been altered through the embodied knowledge that can only be gained through the experience of practice and long association with the culture. Apart from the codified sources, the information modalities are broadened to include social (tacit information that is nuanced towards the collective interpretation of practice and profession) and physical information, which is gained as part of the performance of duties (and includes the routine as well as the unexpected). Experienced officers act in a mediating and interpreting role, providing affordances for novices to engage with the culture of practice, and with the embodied knowledge that comes from long exposure to workplace situations. It is through this interaction, that novices’ professional identity is reshaped to better reflect the nuanced understanding of the collective. This engagement, while reinforcing institutional understanding, acts to reposition novices towards the socially shared mutual understandings of the group and the culturally shared understandings of the emergency service culture. The development of effective information skills is also directed by the collective, who sanction particular forms of information access while disputing the veracity of other forms.

Such practices (although the term information literacy practice is not used) are also evident in the first piece of research into the information practice of a blue-collar worker, a vault worker in a Canadian power company (Veinot, 2007). Social practice theory was used to ‘understand the social organization of workplace actions’ (p. 159). Similar to my own work, Veinot used the concepts of embodiment and the situated context to understand the information practice of this worker. Different from my work, Veinot’s worker creates ‘boundary objects’ that provide information for other administrative and maintenance workers that guide them to take actions. These ‘boundary objects’ connect and coordinate ‘a range of organizational activities, thus satisfying a range of organizational information requirements’ (p. 162). In discussing this, Veinot states that ‘Kelly’s (the vault inspector) reports act as a tool that co-ordinates the works of others, data for statistical analysis, a basis for planning new vaults, and a resource for resolving problems of equipment failure’ (p. 172).

As such, Veinot (2007, p. 172) sees ‘vault inspection work as an information practice’. The range of activities that this practice encompasses includes: situated judgement (using judgement in relation to rules and regulations based on previous experience and knowledge); educated perception (of the visual environment); finding and navigating to the locations; and classification (using situated judgement and knowledge to ascertain the degree of problem discovered, or lack thereof). For example:

Kelly uses her understanding of both the equipment and her organizational context in applying the rules and works with her colleagues to find local solutions to problems with rule application. Kelly’s work is an embodied practice, where she uses educated perceptual skills, navigational skills, and situated judgment to observe and classify phenomena. Moreover the chief mandate of vault inspectors is to produce a report that connects and coordinates the work of a range of other players within the power company. (p. 173)

Exploring the nature of information practice among nurses in Sweden, Johannisson and Sundin (2007) draw on the concept of neopragmatism in order to advocate information practice as a social practice. The authors acknowledged the relevance of ‘communicative participation’ between participants given that library and information studies research is based on communication. Nurses in this study were seen to have ‘context bound dealings’ (p. 200); this reflects much of the literature on workplace information literacy as being context specific. Nurses discussed their, and other nurses’, information use, seeking, evaluation and in some instances production of text, irrespective of format (e.g. documents, articles, books and websites) but one within the context of being a professional ‘community of justification’, i.e. one that is ‘permeated by power relations’ (p. 204) and ‘making specific knowledge claims as to what should be included or excluded from the specific area of expertise’ (p. 203). The authors’ analysis revealed at least two levels of discourse that promoted specific interests of the profession: ‘… the science-oriented medical discourse and the more holistically oriented nursing discourse were two tools employed in the nurses’ accounts of their attitudes toward the production and use of professional information (Johannisson and Sundin, 2007, p. 215).

Commenting on the relationship between medical and nursing knowledge, the authors see the specific positions of nurses and doctors are fixed according to a specific knowledge hierarchy.

The research of the above authors demonstrates that research into information literacy can extend beyond the skills-based approach. However, further work is needed in this area in order to develop the rich descriptions that lead to conceptualizing information literacy practice as a complex process that extends beyond experiencing information through text.

Issues for workplace information literacy

The concept of information literacy as a set of ‘generic skills’, a theme often promoted in the educational sector, is brought into question in workplace research and leads us to ask, does information literacy taught in one context transfer to another context? The substantial body of literature in cognitive and situated learning studies, which has examined transfer of learning, appears inconclusive on the issue. This is primarily related to whether a cognitive or situated learning perspective is adopted. From a cognitive perspective, there are some strong arguments that suggest that in some aspects of transfer the answer is ‘no’. Alternatively, from a socio-cultural perspective, which emphasize co-participation and context, the answer is not so clear-cut because of the recognition of the importance of other people within the workplace and the affording opportunities for learning to occur. Both positions have implications for arguments about the transfer of information literacy as a suite of generic skills lifted from the education context into the workplace.

Transfer is defined by Detterman (1993, p. 4) as ‘the degree to which behaviour will be repeated in a new situation’. While this appears a simple definition, Detterman conceptualizes transfer as a continuum. Along this continuum is near transfer, which describes the transfer of skills that can occur if the context or situation is similar, e.g. learning to drive a truck after learning to drive a car (Misko, 1998). However, Misko (1998) argues that this distinction may not be as straightforward as this. In a study of the ability of a group of students to retain knowledge and skills in one context and to reproduce the knowledge and skills in a new context, Misko (1998) reported that ‘there was no guarantee that being able to perform a skill in one context means being able to transfer the skill to another’ (p. 298).

The importance of situated activity has been strengthened by Greeno et al. (1993). They draw on socio-cultural and ecological theories in their analysis of learning transfer to suggest that the conditions for transfer are dependent on ‘a person’s having learned to participate in an activity in a socially constructed domain of situations that includes the situation where transfer can occur’ (p. 161). This view of transfer focuses on the situational factors, the structure of an activity and the social interactions that occur during initial learning and transfer (p. 161). Gerber and Oaklief (2000) argue that the tendency to take an academic approach to transfer (i.e. to seek commonality in skill or competency) tends to produce an ‘overgeneralised, decontextualised approach to workplace learning that does not prize the relationships that develop among work teams …’ (p. 179).

In considering information literacy transfer, it appears that near transfer may only be possible and demonstrable when the information literacy practices as they are currently taught in an educational context, transfer into similar educational contexts, i.e. through the different years of university education or from university or discipline-oriented workplaces. Information literacy skills taught in an educational context and relating to educational practices may not be easily transferable to training contexts (i.e. TAFE) or workplace contexts that have their own idiosyncrasies in terms of practices and information dissemination, ones that inform learning about work performance. In this respect, developing an understanding grounded in novice and expert learning may better inform our own practices and help facilitate the possibility of information literacy transfer out of the educational context and into workplace learning performance. It will also provide an understanding of what is actually being transferred and at what level of competency this is occurring.

In the fire fighter study (Lloyd-Zantiotis, 2004) transfer from acting as a fire fighter (subjective position) to being a fire fighter (intersubjective position) is achieved through the development of information-related practices. These are afforded by experts who observe novice practice, identify gaps in their learning, and provide opportunities for novices to access information about the practices of work through guidance, scaffolding and coaching (Billett, 2001). They also require the novice to actively reflect on the affordances in the context of their learning. These activities facilitate the repositioning of the novice away from institutionally sanctioned sites of knowledge, towards the sites of knowledge and the information practices that are valued by the fire fighter’s platoon. These practices act as opportunities to mediate and afford information, thus enabling near transfer and transition from an institutional context to a collective practice and the development of collective competencies.

The issue of transfer appears critical for information literacy practitioners, if they are to continue to define information literacy as a critical practice and as a prerequisite for lifelong learning (Bundy, 2004) outside of tertiary contexts. Within the context of the workplace information use of university administrative workers, Hepworth and Smith (2008, p. 227) concur with Bundy’s view when they state that:

… there is a gap between librarians’ and LIS academics’ conceptions of the skills associated with information literacy that stem from the school and higher education context and the experience of information literacy in the workplace. This is partly because the terminology we use is unfamiliar to people in the workplace but also because of the hierarchical and collaborative nature of work which means that information literacies may be distributed among the work group.

In a study of information literacy training for Australian students studying engineering, Palmer and Tucker (2004), argued that, while information literacy may be referred to as a generic skill because it is seen to underpin all forms of learning, it is not essentially a ‘global, context-free attribute’ (p. 19). This is primarily because experiencing an information landscape and learning how to use the information resources available will depend on developing an understanding of the unique and idiosyncratic characteristics of the context. McMahon and Bruce (2002), following their investigation of development workers’ perceptions of local staff information literacy needs, concluded that danger lies in ‘imposing … another “outside” view of what local workers need’ (p. 22), suggesting that current educationally driven conceptions of information literacy and information literacy practices may not reflect the nature or manifestation in other contexts. They also suggested that: ‘The enabling of local workers to navigate the dominant systems and its associated workplace structures, to access information relevant for their local community, to translate it into their local community context and to communicate it effectively in culturally appropriate ways, are all elements of a project which addresses the information literacy needs of those workers’ (McMahon and Bruce, 2002, p. 125).

Bevan (2003) argues that while information literacy skills may be validated from a conceptual level as generic skills, this labelling of information literacy falls down at the concrete or operational level. This is because it fails to take into account the nuances and social practices involved in the application and practice of information literacy in a context-dependent setting. Exploring information literacy from three research sites and in the context of three specific practices—airline customer service, efficient use of software and use of hypermedia—Bevan concludes that ‘In summary, it informs us that conceiving of information literacy as a “generic skill” that can be separately identified and taught has a tendency to both trivialize its complexity and devalue its importance in the development of workplace skills’ (p. 130).

Kirk’s (2004) investigation of managers’ ways of experiencing information led her to suggest that: ‘the complexity of information use raises questions about the education and training of people for the workplace. IL programmes in schools, TAFE colleges and universities have usually assumed a limited experience of information use and a limited understanding of information’ (p. 197).

The need to dispel assumptions about the perception that people come to a workplace with an already developed cache of information skills and competencies has already been highlighted by Crawford and Irving (2007). Crawford and Irving had been exploring the link between information literacy in secondary and tertiary education and the implications for the workplace. These authors highlighted in their research that while employers generally believe that employees will come to them with information-related skills and competencies, the ad hoc nature of information skill and competency development in further or higher education or at work often results in poorly developed skills and the perception that these skills will adequately equip the employee for work. Crawford and Irving (2007, p. 23) suggest that: ‘It is important therefore to dispel the assumptions that everyone has these skills and competencies at a level that they need, that they are explicitly and uniformly taught within education or are learned in conjunction with information and communication technology or by osmosis’.

Studies on information literacy transfer are still emerging. However, recent research (Ellis and Salisbury, 2004, p. 191) on library skills transfer indicates that library skills training, which may occur in schools, ‘does not appear to be transferred readily into the university environment’. Similarly, Hartmann (2001) reported that the school library experience was unhelpful to students moving into university environments because of different curriculum expectations.

In considering the concept of transfer in relation to information skills, Markless and Streatfield (2006) argue that more attention needs to be focused on the conditions for transfer (i.e. information literacy skills) should be practised in a variety of contexts and that studies should be encouraged to engage students in reflexive practice (i.e. thinking about their information practices and monitoring their own learning in relation to this). The increase in online learning at tertiary and vocational levels will also prove problematic to many workplaces that expect new workers to arrive work ready with a range of skills including the ability to work collectively. Markless and Streatfield (2006) also point out that the disconnected and isolated nature of this learning tends not to foster the deep reflection and critical analysis needed to encourage transfer (p. 23).

Use of information literacy standards and guidelines

While no specific information literacy standards have been developed for the workplace, some attempts have been made to adapt the education standards and guidelines to the workplace. Kirton et al. (2008) found that special librarians showed that they ‘recognise the published (ANZIIL) standards of information literacy’ (p. 252). In particular, Standards One (recognize need), Two (find information), Three (critically evaluate) and Six (understand the social and legal use of information) were included in the authors’ analysis of information literacy. However, with Standard Four (manages information) and Standard Five (constructs new knowledge from new and prior) there was a more varied response, possibly reflecting the nature of the workplace.