{CHAPTER 16}

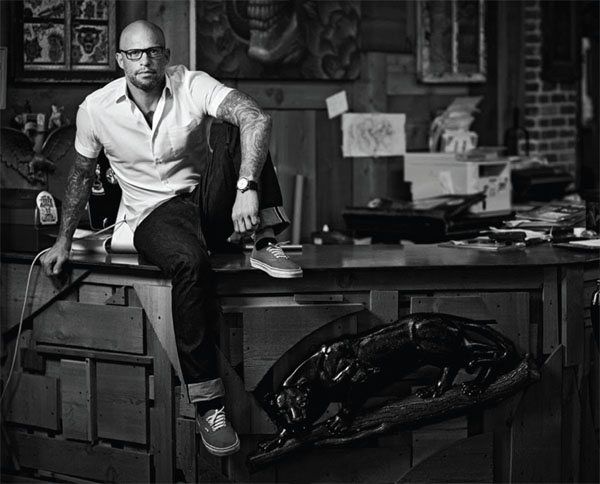

AMI JAMES,

TATTOODO.COM,

AND THE

CLOSED DOOR

In this chapter, we will go online. In other words, we will explore creative opportunities – including for co-creation on the edge between organizations and their environments – that are opened up by the virtual universe. We will meet Ami James, one of the world’s most famous tattoo artists. Ami is taking part in Christian’s new online tattoo project, which we will explain in this chapter. Many creativity researchers feel that the future of creative businesses lies in the digital universe, where the ideals of collaboration and co-creation – which we touched upon in the last chapter – are said to attain their fullest expression. They feel that the sustainable businesses of the future will be small, agile, pervasive, global (or glocal – everywhere and nowhere), and flexible units. They feel that users, customers, and citizens will become integrated into the business in a way we have difficulty imagining today. They feel that, as a result, the creative space at companies will expand through such processes as crowdsourcing, in which the Internet’s potential for information exchange and knowledge distribution is exploited in earnest. First, however, we have Ami’s story, which is in some senses a classic story of the creative life. Then, we will hear more about crowdsourcing, which is today hailed as having particularly creative potential.

AT SKT PETRI IN CENTRAL COPENHAGEN

We interview Ami one Friday afternoon at the café in Hotel Skt Petri in central Copenhagen. Ami has flown in from Miami to complete the final details of a new online tattoo business project of which he is a partner and co-founder along with other partners such as Christian, footballer Daniel Agger, and various other investors. Ami is famous for his breakthrough on the Miami Ink television show, which helped transform the tattoo phenomenon from the underground to the mainstream, and he now operates tattoo parlours across the world. Ami’s work has also been influential in highlighting the potential for online tattoo business.

As Ami sits in the corner of the café, a hat pulled down low over his head, it is difficult to grasp the fantastic story he will set forth over the course of the interview. His is a story of closed doors; of never having passed a school exam; of suffering from attention deficit disorder, which means that his mind is constantly invaded by disruptive thoughts yet also means that he is subject to the constant disruptions that welcome new creative thoughts. In addition, it is a story of how he discovered his own artistic talent and let it lead him.

As Ami says in the interview, “I’ve been drawing all my life. Maybe not like Michelangelo, but it’s been my interest and my passion. I failed constantly in school. The only thing I managed to do was count. I couldn’t read, couldn’t understand, and couldn’t spell. I couldn’t manage my studies, was called lazy. All of this led me toward the art world. That’s where I could really manage. My father and my grandfather had been artists, my father became part of me, and that’s what I wanted to be.” What appeared to be great obstacles for Ami ended up representing a creative opening.

Ami was in trouble as a 17-year-old in the 1980s. The punk movement was raging, the tattoo culture was rough, and Ami’s life was a mess. He made, however, a decisive choice: “I volunteered for the army in Israel, where I was born. It saved me and made sure I didn’t run into trouble. I was a sniper-sharpshooter. It was there I realized I needed to follow the artistic path. I could either shoot or draw people. I needed to save myself. I loved my country, but I didn’t know anything about politics. I didn’t know anything about the conflict between Israel and Palestine. I know most about America.”

As described in numerous interviews in this book, creative people need rules, frameworks, limits, and an extremely disciplined work practice. These can be a necessity and help structure an otherwise wild way of life. The army is, in this sense, a classic example of a highly disciplined societal institution – and it served to save Ami.

Like Andreas Golder, from whom we heard earlier, Ami is equal parts “self-made made” and influenced by a period of apprenticeship. He is also preoccupied with identifying the best conditions for art. When he got his first tattoo, he decided to enter the industry himself. “I decided I wanted to get into it. I’d drawn my entire life. It was just about using a different kind of pen. I began tattooing my own legs. The moment I took up the needle, I knew I wanted to be a tattoo artist. I had to spend the last two years in the army though. I sort of got a glimpse of my future, but I couldn’t leave the army immediately. After my time in the army, I returned to Miami. For my birthday, my brother’s best friend bought me a tattoo parlour sign and a box with a tattoo kit. It was like getting a million dollars. It was the greatest gift. That box changed my life. It became a way for me to express myself, a way to live. That box became my life.

“After I got the box, I just started making tattoos. Obviously, no one’s born a fucking Picasso, but that box gave me the opportunity of my life. I had it the next 20 years. That man had changed my life. Eight months later, I got an apprenticeship, and the master became like a father figure to me. He taught me how to tattoo. He was extremely hard on me, and we fought all the time. It lasted two years. He died of an overdose, and my entire career was based on making him proud of what I did. I wanted to be better and better. It was a bit crazy. I was out every night trying to find someone I could tattoo the next day. It’s street art, the finest form of street art. We found people just walking around. It wasn’t a high-end market. It was real workman-like. All I owned was my skill at making tattoos. I needed to use my art on others and make it grow. I hadn’t thought of it as a way of becoming famous. I was just a happy artist. It was only 14 years later that I got a TV show. Until then, tattooing hadn’t given me anything except that ability to be around cool people. In terms of business, it didn’t offer anything.

“Since I got the opportunity to do TV, I got the opportunity to expand this. I’ve considered the fact that, in reality, maybe, I can only do two things – draw and tell stories. And the fact that I can use my mouth became my path to fame. And of course, I have my own style. I’m definitely not a better illustrator than so many other people, but I can tell stories. I know what can put on a good show. I search for stories, how you can relate to other people, get them to understand. I was good at that. I knew it would shine through on TV. I want to be the best version of myself – not the best or famous. I just want to be myself. The guy who bought my programmes ended up selling the TV channel for 40 million dollars. Finally, I opened up my own shop.”

For Ami, being a tattoo artist is more than just a job. It has been a means of survival. These days, although it has become more of a job for Ami, he remains driven by a strong belief in tattooing as both art and craft.

Ami does not limit “the artistic” to the making of pretty drawings but also regards it as a means of self-expression through such activities. “You can see the most fantastic work, but it isn’t art because it’s just a copy of something. And in fact, there can be so much originality that the craftsmanship isn’t an issue. There are so many genres and so many people. Some can just do it. They draw from the images they create, whereas others need the copies. I get inspired, but I can also be intimidated by other works. It’s important not to start comparing. Maybe your own stuff will never be that good. That’s why you need to find your own style. The great masters never end up like others. Of course, you need to have your references, but you have to build on them and find your own voice. This means you have to study: how have people done it the past 20 years? You have to learn the basics, what’s right and what’s wrong, and after that, you can draw whatever you like. You have freedom of expression. But it’s not necessarily happy or free of demands. You still need to be able to go to work, get started, and then the inspiration pops up, maybe. This requires that you can imagine yourself in the future, that you see yourself in the future. And when you love what you do, you’ll almost always do what’s right, even if there will always be mistakes. We’re not machines. Even the best make mistakes. It’s just our nature. There’s always something you could’ve done better.”

Ami has discovered his own seam of creativity, hidden away behind corridors of closed doors, craftsmanship, and an urge to find his own voice. Before we leave Ami, we ask him whether he uses drugs to stimulate his creativity. This has been a theme in some of our other interviews, although often as something that the interview subjects reject. Here, Ami proves different, perhaps because his attention deficit disorder often leads him off track.

“I use hash. It keeps me calm. It allows my subconscious to keep working. It’s good for the drawing. Sometimes, I smoke all day. It opens yet another window. But there’s so much I haven’t got done. It makes everything else silent, and I get so deep that I don’t want to take breaks. I can’t stop drawing. I don’t sleep. My personality changes when I’m doing tattoos, so I’m four years old, and I’m slow. You can ask me something 1000 times. It’s another zone. So it takes me a bit of time to come back.”

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM AMI’S STORY?

A recurring theme in this book’s interviews is that quantity begets quality. This also emerges from Ami’s story. Tattooing became Ami’s means of survival in Miami – to such a great extent, in fact, that he rarely used money. His tattoo craftsmanship became his “currency”. In other words, he made tattoos for people at bars, restaurants, and so on to get something to eat and drink. It meant he was doing tattoos constantly, for many hours a day (as with Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours). That is why he developed a fantastic ability for craftsmanship without actually having this as a goal.

During the interview, Ami insists that he has attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Some researchers feel that people with these illnesses are very creative and that their unconscious shifts in attention could, perhaps, be essential to their creativity. It could be that too much focus inhibits creativity. Once we stop focusing on the issue, we allow into our heads new thoughts that can stimulate new solutions (see also http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2011/02/08/adhds-upside-is-creativity-says-new-study.html;http://psychcentral.com/news/2010/02/25/adhd-may-be-associated-with-creative-genius/11713.html).

One final conclusion, which is interesting in light of this book’s previous chapters, is that Ami has what seems to be a quite pronounced attitude toward drugs. For instance, he mentions in the interview that he never drinks coffee or other caffeinated drinks because he finds that it worsens his attention deficit disorder and makes him jumpy. For the same reason, he never takes drugs like cocaine or speed even though he smokes grass/marijuana. Perhaps this is because it lowers his energy and makes him think slowly, which we have seen noted as constructive for creative processes a number of times in this book.

We leave with Ami’s uncompromising and absolutely clear conception of what creativity requires: time, immersion, ability to overcome resistance, professional knowledge, craftsmanship, finding the right master, the desire to express one’s own voice, and a joy in creation – one that can periodically overshadow all else in your life.

But let us return to the start of this chapter. What kind of project is Ami involved in, and why has Christian decided to invest time and resources in tattoos?

TATTOOS AS BUSINESS – ON THE EDGE?

To understand how tattoos can be considered a new business area in 2013, we must briefly consider the history of tattooing. Why do many people regard it as a particularly controversial business area? Unsurprisingly, the answer to this question begins with us heading out to sea.

Between 1766 and 1799, Captain James Cook undertook a series of voyages to the South Pacific, including to Polynesia. Upon their return, Cook and his men spoke of the “tattooed savages” they had met. The word “tattoo” itself derives from the Tahitian word “tatau”. In the ship’s log for the boat Endeavour, Cook notes in 1769 that “Both sexes paint their bodys, tattow, as it is called in their language. This is done by inlaying the colour of black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible.” The word “tattoo” thus comes from the Tahitian “tatau”, which becomes “tattow” in Cook’s version.

In the event, after Cook’s return to England, the custom of tattooing was received with keen interest by the royal court, eventually leading even so high-status an individual as the future King George V to have the Cross of Jerusalem and later a dragon tattooed on his forearm. In time, tattoos came to be associated with – in the best case – being a sailor or – in the worst case – being a criminal, prisoner, prostitute, or gangster. Tattoos have been stigmatized ever since. Today, however, tattoos have become far more mainstream, in part through Ami James’sz work. Nevertheless, it remains a business area avoided by professional investors, whether venture capitalists, investment banks, or private investors. This is why, as of 2013, there are still very few online-based tattoo-related products and websites. This means, of course, that there is a gap in the market and a possibility for staking a claim to a corner of an industry that, all things considered, can boast some pretty impressive statistics. For instance, approximately 40% of all Americans between the ages of 26 and 40 have tattoos. In terms of an online business model, it is interesting to note that Internet searches for the word “tattoo” or related search terms such as “koi carp + Polynesian + tattoo” occur around 140,000,000 times a month. In other words, there is enormous potential.

Tattoodo.com is thus an example of an online business model within a new and much-discussed area, established by people – including Christian and Ami – who are themselves great lovers of tattoos. The website is a sort of Google for tattoos, a go-to platform for everything related to tattoos. Christian became aware of the creative potentials online when he acted as the first-ever Danish speaker at the Google Zeitgeist conference in London. At this event, Larry Page explained that specialized search engines could come to be one of the greatest threats to Google’s dominance.

At the moment, Tattoodo has five primary revenue drivers, of which the first is a crowdsourcing model whereby one can have one’s tattoo design customized by uploading criteria in the form of text, one’s own illustrations, or photos. These are then used as the basis for a competition to which tattoo artists, designers, and illustrators from across the globe can contribute their designs. All contributors are personally approved “Ami official Tattoodo.com artists” to ensure quality. In other words, if you upload a photo of your girlfriend, a quote from your favourite poet, and a picture of your favourite flower, hundreds of people from around the world can – for prices as low as $100 – offer you unique designs that combine these elements.

Crowdsourcing is one of the best examples of what happens when you break down barriers between yourself and your company – when you balance on the edges. Crowdsourcing websites are going from strength to strength, to the extent that 99 Designs is now the fastest-growing design website in the world. The last three logo designs and corporate identities that Christian has had made for his own companies were, for instance, produced via 99 Designs. Here, you set out criteria, start a competition, and wait for people from all over the world to offer designs for your logo, website skin, graphic artwork, or whatever you require. These sites, with Innocentive.com being an example, also exist within the field of inventions and the more scientific product areas, and they can be a fantastic means of implementing creative processes, allowing you to use crowdsourcing to “close the gap” between yourself and your work or project. This is not, of course, intended to take work from skilled, trained designers, but rather to offer them a platform they can use as a creative springboard. If you have got stuck in a rut in an R&D assignment at a foodstuffs company, one means by which employees could offer a new formula or combination of ingredients could be via Innocentive.com. At hummel, designers can also request new graphic lines via 99 Designs. This can give them the opportunity to reformulate or redesign and thereby move along the edge and attain something that adds value.

Interesting in terms of the preceding is also crowdfunding, by which one finds financing or companies in which to invest on the edge of the box between oneself and one’s surroundings. Relevant examples include Rockethub.com, Kickstarter.com, and fundedbyme.com. Besides Innocentive.com, Geniuscrowds.com is also an extremely good website of which to make active use when it comes to making that first brushstroke, to quote Andreas Golder earlier, in this case within the fields of inventions and the sciences. Tattoodo.com possesses a readymade revenue stream in the form of a high-quality selection of tattoos created by world-class masters, both those now living and those of the past. Customers gain access to this easily navigable tattoo library as part of the package, which also includes an artwork certificate and stickers that allow you to test in advance where the tattoo should be placed. Besides these revenue streams, there will be a large amount of free content, advice, blogging, people speaking about their experiences, and tattoo designs. Everything will be beautifully packaged, which is not the case in the market today. The reason for this is to guide tattoos into a more mainstream lifestyle sphere so that the website does not merely preach to the choir.

In other words, there is creative potential in the virtual world. What is interesting is how this could, in the long term, change our perception of who is permitted to be creative. Is it a company’s internally employed designers and product developers – or the customers? Many businesses – for instance, LEGO – have had to enter into collaboration with customers via crowdsourcing because the very dedicated customers would otherwise represent a potential threat. If LEGO did not collaborate, then the customers would take the lead and develop things for themselves. This can be a quick process in a digital world because one need not have a polished administrative apparatus in place to succeed. You can use the Internet to rapidly contact customers and suppliers outside of the old network. In this case, we can ask what role the internal product developers and designers now play. Perhaps they serve primarily as role models – like Ami – or as those who, despite everything, are familiar with the domain’s values and criteria for quality and who can thus take on new roles as “judges”, as those who evaluate whether the plethora of new ideas that swarm in from external teams actually have potential. This represents a fairly radical change in the roles that designers and product developers play, yet there is no doubt that the Internet offers democratizing potential in this sense. The organization that has not understood that external innovation is at least as important as internal organization will run into problems in an open, virtual economy that is widely regarded as more creative than ever before.

In the next chapter, we will move slightly away from this commercial focus on creativity. The previous cases have illustrated the importance of creativity for success at knowledge-based businesses, which are now extending into a virtual universe. Now, we will grapple with the issue of the role of schools and the educational system in this context. We will take a trip to Herlufsholm, a hallowed boarding school in provincial Denmark. Herlufsholm has found that creative thinking is important for students. As a result, the school is engaged in a lengthy process of attempting to realign the ideals of what a good school is capable of.