CHAPTER 8

Follow-Up on Accountability: Administering the Appraisal System

It is one thing to develop a solid set of performance standards but quite another to successfully implement it. In my experience, one of the biggest problems, if not the biggest, with performance management in government is the lack of follow-up by supervisors. This often dictates whether the organization is successful in managing its employees’ performance

Whenever I speak to or work with government organizations, I constantly hear that this is one area where almost everyone struggles. Whether that is the result of a lack of knowledge, limited time, a culture that moves problem employees around, weak support from upper management, or some other factor, poor performance must and can be dealt with if the organization has the will and the skill. There are specific ways to administer the appraisal system to improve performance management in your organization, so let’s talk about how to do just that.

First of all, if you do not have good standards, follow the advice I provided in Chapter 7 and develop them. Include the employees and the union, if you have one, in the process, since transparency will improve the credibility of the standards. Carefully listen to their comments, criticisms, and suggestions, since it is better to be aware of these concerns early on and address them at that time if necessary, rather than have to deal with them when you are before a third party.

Managing the Individual Employee

Assuming you have provided the employee with the training, tools, and expectations (discussed in Chapter 6) and have developed the requisite performance standards, the next and most important step is to manage each employee’s performance. Simply put, the key here is communication—tracking how everyone is doing and then giving employees fair and frequent feedback.

Unfortunately, many if not most government supervisors spend relatively little time and energy talking with the employees about their performance, which often leaves the employees unsure about how they are doing and gives them the impression that their boss is not particularly interested in them.

The little time that supervisors and employees spend together discussing individual performance goes something like this: During April (the midpoint of the appraisal period), the supervisor has a brief conversation with each employee and tells him that he is “doing fine.” The supervisor asks no questions and then quickly presents the employee with the appraisal form to review, letting the employee know that she is in a hurry and has to meet with the next employee. Invariably, the form contains a box that has been checked by the supervisor indicating that the employee is performing at the fully successful level; there are no comments anywhere. She then asks the employee to sign the form, which he dutifully does. That ends the discussion about the employee’s performance, and another one does not take place until six months later, when the appraisal period ends.

At the end of the appraisal period, both the supervisor and the employee start to become a bit uncomfortable. From the employee’s perspective, he has received virtually no feedback throughout the year regarding his performance. He is reasonably certain that he will not be fired because no one ever seems to get fired; by the same token, he has no idea whether he will be rated “outstanding,” “highly successful,” or “fully successful.”1

From the supervisor’s point of view, she has to rate a large number of people to whom she has given virtually no feedback during the year. Moreover, she has to decide how to appraise employees against performance standards that are very vague. What usually happens is that she sits down with her supervisor(s) in a room behind closed doors, and they decide by gut the level at which each employee will be rated. The criteria are, of course, questionable, to say the least, and the people whom management likes the most wind up with the highest ratings, even though there is no factual basis to support these determinations.

The supervisor leaves this meeting knowing that there is strength in having upper-level management support her ratings but also with a knot in her stomach because she now has to explain the rationale behind each rating to her subordinates. She then meets with each employee as required and tepidly presents them with their ratings. If anyone receives a rating below outstanding and objects, she simply plays the role of the victim by implying that upper-level management made her do it and, if she had her way, she would have rated the employee higher.

From the employee’s perspective, he sees that appraisals are less a function of what you do relative to the performance standards and more a function of whom you know and/or how well you kiss up to management. In most cases, he will not want to ruffle any feathers by filing a grievance or EEO complaint, but he will privately sulk, most certainly complain to his co-workers, and slowly but surely become cynical and at least somewhat disaffected. Is this any way to run a government?

Fortunately, there is another way of managing employee performance that will make everyone feel better and, more important, result in improved performance. The key, as I mentioned earlier, is communication, and by this I mean frequent, honest, and, where necessary, detailed interactions between the supervisor and the employee. Let’s examine what I mean by this.

The supervisor should be talking to the employee about his performance much more frequently than twice a year. Employees need and deserve that feedback, and it is the right thing to do. In addition, when you have to do something to the employee that could be viewed as a negative action (ranging from a counseling letter, to a performance improvement plan, to giving the employee “only” a fully satisfactory rating, to not giving the employee an incentive award),2 it will always be received better if the employee can see it coming, and the only way he will see it coming is by having more frequent communication that emphasizes what he can expect on the basis of his year-to-date performance.

I recommend that supervisors communicate with their employees at least quarterly, although I think that monthly is even better. The communication doesn’t always have to be a face-to-face meeting; it can simply be a written note and/or form that lets them know how they are doing relative to their standards (both the fully successful and the outstanding levels) and their peers. In this way, the employees know exactly how they are doing with respect to both retaining their job and achieving awards. There are no surprises and no secrets, and as long as the supervisor then appraises the employees according to the guidelines of the standards, every employee will be able to predict what his appraisal will be and whether he will receive an award. In other words, the system will become meaningful and credible to the employees because it will be reliably applied to them. I tried this exact approach in my last office, and employee satisfaction with this approach rose by more than twenty points because the employees saw that this was a system they could believe in.

A good way to communicate on a monthly basis is by giving employees a simple report card that provides the information I described two paragraphs ago. Such a card lets them know how they are doing and gives them the opportunity to raise any concerns they may have about the numbers. Moreover, it provides the supervisor with the opportunity to give the employee feedback (“great job, keep it up”; “you’re doing just fine, thanks for all of the good work”; “I think you could do better, especially in quality, where your error rate is too high”; “if you don’t increase your productivity by at least 1.5 widgets per day, I am going to have to officially give you a counseling letter”). The point here is that by issuing monthly report cards, you can give the employee immediate feedback and positively reinforce excellent performance or prod the employee to improve his performance when necessary.

This is an example of a monthly employee report card.

Figure 8-1. Sample Employee Report Card

As I have stated earlier, some positions are not that easy to measure, so monthly report cards probably won’t work for them. Under those circumstances, quarterly conversations or a brief note letting the employee know how he is doing should suffice. The point here is that the better you communicate with your employees about how they are doing, the easier it will be for you to manage their performance.

Managing the Performance of Your Group

While managing the performance of each employee is extremely important, from the supervisor’s perspective, managing the performance of the group is even more important. After all, the supervisor is evaluated on the basis of the performance of the group as a whole, not how each employee performs as an individual. Of course, to a large extent, the performance of the group is a function of the way the employees perform as individuals. However, the way they interact and work together as a team is what it is all about.

So how do you get the employees to work together as a team? First of all, remember the basic premise behind this book: If your systems are properly aligned, your employees will all focus on what is important to the organization, and this will bring a high degree of synergy. This means ensuring that people have the right training, tools, and expectations; making certain that the physical plant promotes a reasonable degree of interaction among the employees; and ensuring that the performance standards and rewards programs recognize both group and individual achievement. Second, you need to establish good communication between management and the employees and between the employees themselves, since that will also contribute to the group working as a team and not just as a bunch of individuals. Along these lines, I highly recommend that you hold a team meeting at least once a week, if not daily. The purpose of this meeting should be to discuss performance, share information, and gather everyone’s perspective on the key issues confronting the team. In essence, the team’s performance goals are the anchor for the team and what everyone should focus on.

I firmly believe in posting both individual and group performance on the team’s bulletin board.3 The idea behind this approach is to share virtually the same information with the employees that management has so that they feel more connected and more responsible for achieving the goals and objectives of the organization, instead of merely standing idly by and not getting involved.

That having been said, posting individual performance information generally works best when multiple members of the team have the same positions and performance standards and their jobs are relatively easy to measure. Under these circumstances, providing such information to the employees gives them a greater sense of context regarding how they are doing; demonstrates a high degree of transparency; prevents the supervisors from protecting their favorites and/or going after good performers that they don’t like; and almost forces the organization to reliably treat all of their employees according to the numbers.

By the same token, such an approach normally prompts a high degree of internal discussion, as employees want to know why some people are doing much better than others. They quickly start to recognize that, to a large extent, overall performance is a function of the sum of its individual parts and try to pull up the weaker employees. In addition, people at the bottom of the performance spectrum will realize they can no longer hide and will make a concerted effort to improve as long as they are convinced that management is serious about dealing with poor performance.

Posting individual employee information can be controversial, since at least some people (usually the weakest employees) may feel that such an approach violates their privacy. In order to address this concern, I advocate posting the information anonymously, using a number or symbol, rather than a name, to identify each employee’s performance. By taking such an approach, you allow everyone to see how she is doing and how each of her peers is performing, but she won’t know whom the symbols represent. Of course, don’t be surprised if the employees talk to each other and figure some of that information out; however, that is between them. If they decide to share such information, everyone ultimately profits because you will have greater communication and significant upward peer pressure.

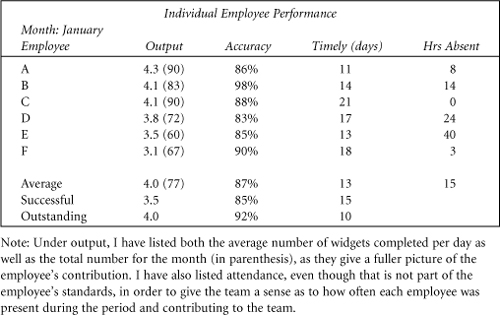

Here is an example of what posting individual performance within a team might look like:

Figure 8-2. Sample Posting of Individual Employee Performance Information

As you can see, this type of information provides the team with powerful information about how everyone is doing and lets team members identify individual gaps that they can address in order to improve the team’s overall performance.

When I was detailed to another organization, I asked a section chief to try this concept within his area of jurisdiction. He agreed and reported back to me just two weeks later that he was amazed by the reaction. People started asking all sorts of questions, wanting to know what they could do to increase their performance, why some people were not pulling their weight, and so on. He was thrilled by the increased energy and focus and how it translated into improved performance within his team.

Dealing with Poor Performers

I covered this topic extensively in two of my previous books,4 so I am not going to spend as much time on it here. The key to dealing with poor performance is to communicate with the employee and address it early and to make a good-faith effort to help her improve. If that doesn’t work, you move to the formal stage (the Performance Improvement Plan, or PIP). Be firm but fair, apply the system as intended, and don’t hope the problem will go away.

Addressing performance problems head-on is the only way to go; if you do that, everyone will get the message you are serious. Moreover, the employees themselves will resolve many of the performance issues once they realize that if they don’t pick things up and improve, management will take action.

On the other hand, if you dillydally, people will not treat you seriously, which will then force you to spend a lot more of your precious time prodding the poor performers to step it up—and they won’t. Remember, everyone watches what management does. If people see that management will not tolerate poor performance, the vast majority of employees will silently applaud you. The bottom 10 percent, naturally, will not, but they will take the message that they had better get cracking or they may be out of a job.

Firing poor performers is really not that difficult as long as you follow the process, try to assist the employee, and have good documentation. The burden of proof (substantial evidence) is relatively low, and management’s success rate before third parties is relatively high (80–85%).

If you stay the course and treat everyone the same, you will do just fine.

A Note About the Supervisors

This book has focused on improving performance by managing through systems. The basic premise has been that if you have well-designed systems that are properly aligned and that work together, they will positively impact on the knowledge and culture of your organization, helping your employees to deliver the results that you are looking for.

That having been said, do not underestimate the importance of your supervisors in making these systems work properly. After all, in my experience, if you have good supervisors working with bad systems, they will eventually work together to try to improve those systems. Conversely, if you have bad supervisors working with good systems, they will eventually find ways to undermine the systems by not properly applying them, treating the employees in a disparate manner, and so on. That is why the supervisors are so crucial to an organization’s success and why you need to focus so much of your attention on developing them and ensuring that they are implementing the systems as intended.

I recall earlier in my career giving what I thought were excellent speeches to the troops, only to later find out that some of the supervisors were telling their employees to disregard my remarks. In essence, their message was that I would be around for only a relatively short period of time, so the employees should listen to the supervisors and ignore me. I realized that unless the supervisors were on board with the direction I wanted to take the organization, they would be a major stumbling block in any change effort that I wanted to undertake.

I decided to spend quite a bit of time sharing my vision and values with the supervisors and bringing in outside experts to try to develop them. Some of them definitely came around and became change agents, while others did not and remained rooted in the past. Eventually, I concluded that I could not go forward with supervisors I did not trust and who were likely to be at odds with the direction I wanted to take the organization. As a result, I had to replace roughly half of the supervisors,5 which was painful but, in retrospect, absolutely the right thing to do.

The point here is that if your organization is experiencing performance problems, the odds are that your supervisors are probably part of the problem. Some of them may simply be technicians who are in the wrong position; they may lack knowledge or experience; they may not be willing or capable of dealing with difficult people; or it may be a function of their attitude.

For example, I recall one supervisor who had a sign on his desk that said, “What part of ‘no’ don’t you understand?” Not exactly a positive message, was it? Another supervisor was a nice person, but she was also a procrastinator and always had an excuse as to why she couldn’t meet her goals. A third supervisor was strong and tough, but she treated the employees so harshly that no one wanted to work for her out of fear of incurring her wrath. Regardless of the reason, if your supervisors are contributing to your performance problems, you need to address this issue pronto.

My advice is to confront each of the supervisors you deem to be a problem and be honest and straightforward with her. Let the supervisor know you consider her to be a problem, tell her why, and explain to her what she needs to do to improve. Make a good-faith effort to help her, and give her a reasonable amount of time to show she can meet your needs. If that doesn’t work, deal with her as you would with any unsuccessful employee, and find someone else who can do the job.

Remember that your people system is one of your most important management systems because it impacts upon the folks who do the actual work of the organization—your employees. Since this system is so critical to your operation, it must be administered by competent and well-trained supervisors who have good attitudes and are willing to deal with difficult situations. In other words, if you are unhappy with them, either you change your supervisors, or you change your supervisors.

Holding employees accountable is one of the most important jobs of a supervisor. If you do this well, you will honor and recognize outstanding performance; let the successful people know that they are performing in an acceptable manner but also show them what they need to do to take things up a notch; and assist poor performers to improve. If all else fails, you will take appropriate action. If you develop these skills you will quickly see a noticeable improvement in your organization’s performance. This will happen because the employees will finally believe that you are serious about performance management and that unacceptable performance is exactly that: unacceptable.