HOW TO SELL YOUR WORK

GET REFERENCE

When you come up with an idea, you probably have a picture in your head of what you want the finished piece of work to look like. But to sell it to others—your creative director, the account team, the client—it’s essential that you get “reference”: images or film clips that will help them see it.

Of course, there’s a danger that if you show people reference of something similar to your idea, they’ll conclude that what you’re proposing is not original. For that reason, you should only ever be producing reference for an executional style or technique, never for a strategy or an idea. There’s a big difference, because taking a style from one artform and applying it to a completely different arena can produce something that feels totally original. But starting with an unoriginal idea will always produce unoriginal work, however you dress it up.

Not everyone needs to see reference—some of the people you present your ideas to are perfectly capable of visualizing from a script or a scamp. But many aren’t. There are lots of people in this business who are great at marketing or strategy or account handling, but who couldn’t visualize a red bottom unless you show them a picture of somebody being spanked. (This doesn’t make them bad people, incidentally. They just need your help.)

The importance of helping them see it is that if people don’t know what your ad is going to look like, they might not realize how good it is, so they might not like it as much as they should, so they might fail to sell it (account team) or buy it (client).

GET THEM TO SEE IT YOUR WAY

Even if they do buy it, the fact that you haven’t fully explained what it’s going to look like means everyone will start visualizing it in their own individual way, and might want it executed their way. You don’t want that. You want it your way. Also, once people have formed their own picture of something, it can be hard to get them to change it. This will cause arguments further down the line; the kinds of arguments that steal time and sap your energy.

Of course, you don’t want to spend hours and hours collecting reference for a route, only to watch your creative director blow the whole thing out in 30 seconds. So start small. You may start with just an image, for presentation to your CD, and then step up the amount of reference you show as the process goes along. But you certainly don’t want to start too late. Some creatives only look for reference when an idea is just about to go to the client. I think that’s a mistake. John Webster, perhaps the greatest-ever British creative, never showed an idea to anybody—even the lowliest account handler—without reference. From the very beginning of the process, he made people “see it”—and he made them see it his way.

Nick Gill, the executive creative director at BBH in London, who is generally thought of as one of the UK’s best writers of TV commercials, often presents his TV scripts along with the music track that he has in mind for the ad. It’s amazing to what extent the “right track” helps people to understand his idea, brings it alive for them, and makes them like it more.

Nick sometimes draws his own storyboards too. He often has a movie scene that he’ll play people as a reference. And he’s not afraid to act his ads out to the room. Compare that with the typical creative, who simply reads out the script in a flat monotone—or even just hands it over and asks people to read it for themselves. Nick understands that it’s difficult for people to “buy” a mere script on a page. So he doesn’t ask them to. Instead, he does anything he can to bring his script to life. It’s no wonder he gets so many of his ideas made.

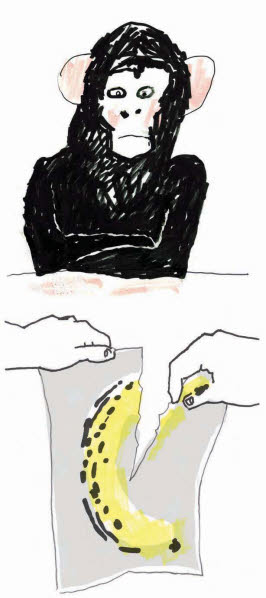

Top: This is what a typical “scamp” looks like—a simple black-and-white line drawing that explains the concept.

Bottom: And here is the finished ad.

PRESENTING TO THE CREATIVE DIRECTOR

The way a creative presents his work should vary according to whom he’s presenting—clients like a lot of fluff and preamble, account teams a little bit, creative directors don’t like any. I mean it—nada.

Why? Because the first thing to remember about presenting to your creative director is that he is short of time. His day consists of meetings, a sandwich, and then more meetings. His Blackberry pings ceaselessly. Everyone in the agency needs his opinion, his approval…I have seen account handlers follow a CD into the toilet to get time with him.

So the biggest favor you can do your creative director is to make things quick.

That means no preamble.

All you do is remind him which brief you’ve come to show work on. That’s important. Because while you’ve been working on this solidly for a while, and it’s uppermost in your mind, he might not have given it a thought since he signed the brief off two weeks ago; he may not even know what you’re here for.

So you walk in and say: “Hi, Steve. We’re here to see you about Toyota, that ‘reliability’ radio brief for the Camry.”

You mention which brief it is, and maybe what the proposition was, just to focus his mind, but that’s it.

Don’t go through an explanation of why the work you’ve done is right. The consumer won’t get an explanation before he sees the work; your CD doesn’t want one either. All he wants is to see the work. Nothing else.

HOW?

So how should you present that work?

As simply as possible. If it’s a TV script, an old cheat is to write what the idea is at the top of the page. That makes it easier for him. If it’s print, have it simply drawn up, or Mac-ed up, if necessary. If it’s digital, put it in whatever form comes across most clearly. Remember—the quicker an idea is to “get,” the more people think it’s good. Don’t forget to bring reference (though if you’re presenting several ideas, you wouldn’t be expected to have reference for all of them).

But whatever you do, don’t use PowerPoint. Not that there’s anything wrong with PowerPoint; there’s actually a lot of cool stuff you can do with it. But if a creative tried to, he would probably be carted off to the loony bin. Why, I don’t know; after all, it’s just words and pictures. Nevertheless, the use of PowerPoint in creative circles is considered actively evil. So do not learn how to use it, and if for some reason you already have learned it, unlearn it. Fast.

WHEN?

As you can see, how you present to your creative director is a matter of the utmost simplicity. The trickier question is when you present.

Do you wait until you have an idea that you would die on a sword for?

Or do you go in when you have four or five ideas that you like, and rely on him to pick out the best one—after all, “that’s his job?” Or do you go in with “a few thoughts,” and aim to work with him collaboratively, to turn one of them into something good?

I remember one boss I had, years ago, telling me “I want you to run in.” By which he meant “don’t show me any work until you’ve got something so exciting you just physically can’t hold yourself back from sprinting into my office.”

He hadn’t taken on board that his title—creative director—implied he should be giving the creatives some direction, rather than just waiting for them to come in with the answer. But to be fair, that kind of laziness is rare. After all, if every team could get to the answer without help, then there would be no need for creative directors, and he wouldn’t have a job.

At the other end of the scale is the “bring me your wounded, bring me your lame” attitude—in other words, show me anything you’ve got, and let’s see if we can make it work. Apparently David Droga tries to see all of his teams every day. His attitude is that as a creative, time is your only resource. And he doesn’t want his creatives wasting any. He doesn’t want them working for more than 24 hours on a thought he might not like; he’d rather see all their half-thoughts than one or two finished ones.

So the answer on when to present depends on the attitude of your creative director. Every CD is different. You need to learn—as quickly as possible—whether he likes to see a lot of ideas, or whether he prefers that you do more culling first.

If you are getting too many insults—creative directors specialize in the finely honed insult—then this is a clue that you are going in too early. (We once showed something to Jeremy Craigen when I was at DDB and he said: “That is a really good ad...for Publicis Bratislava, maybe.”)

As a general rule, the more experienced the team, the fewer ideas you should be showing, because you should have a better idea yourself of what is good. Therefore, young teams should go in with several ideas. Young creatives often have great ideas that they don’t know are great, because they don’t have the experience to recognize it. So go in early, go in often, go in with anything you’ve got that’s coherent, draw stuff up clearly but not beautifully, and don’t invest hours crafting dialogue. After all, you don’t want to spend days buffing up your gem only to be told by your CD that you’ve been polishing a turd.

By “the team” I mean account handlers, planners, engagement planners...anyone at the agency who works on the account you’ve been briefed on.

By way of example, let’s look at how a well-known campaign idea might hypothetically have been presented. Bear in mind I have no clue how Tom Carty and Walter Campbell, the creatives at AMV.BBDO in London who created “Good Things Come To Those Who Wait” for Guinness, actually did present it, and I’ve never met either of them so I’m no doubt completely misrepresenting their personalities. But I like to think the meeting went something like this...

BRIGHT AND BREEZY

Tom and Walt: “Morning all. Hi! Come on in. Everyone got a seat? Great.”

The point to notice here: Tom and Walt have begun the selling of their idea before the team even sits down.

Tom and Walt have adopted a bright and breezy manner. They are friendly and open. Do they particularly like this account team? Maybe, maybe not. But they understand the importance of projecting confidence. They understand that at this crucial moment—the first presentation of an idea—the account team will be scanning every sound and gesture that they make.

You see, the account team has spent weeks or months developing this brief, and they have had endless conversations with the clients and the creatives about it. Finally they are about to see the result. Their curiosity is rampant. And what they basically want to know is one thing—have the creatives cracked it? Have the creatives produced something they believe in; something the account team should believe in; something the whole agency should get behind; something that might be a career-changing piece of advertising for everyone who comes into contact with it? Admittedly, that’s more likely for the next Guinness ad than it is for, say, a small-space print ad for a trade publication. But even with the smallest ad, there are stakes. If it hasn’t been cracked, the account team may be facing a world of pain.

Accordingly, if you have cracked it, be confident. Signal it. If you haven’t cracked it, and this is going to be a playing-for-time meeting, then signal that too. Start with a frown and a sigh. Manage their expectations. Tell them that you don’t think you’ve cracked it, but you’ve got something that may start an interesting discussion. Tell them you’ve got more questions than answers at this point. And then do actually have lots of questions. Convince them you have the desire and the energy to crack it next time. Otherwise, the next time they come in, they walk in hostile.

THE PREAMBLE

Tom and Walt: “As you’ll remember, the brief was all about how Guinness has more substance than lagers do. It’s even reputed to have health benefits.”

This is what we call a preamble. Account teams don’t like ideas to be presented cold; it makes them uncomfortable. They love to start the presentation with a quick recap of the brief. And this seemingly meaningless ritual does in fact have an important purpose—by demonstrating to the team that you have been working to the correct brief, you are providing vital reassurance, and making an advance claim about the saleability of your idea. Both good things.

The preamble puts the account team in a reassured and receptive state, and the state we are in when we receive information has a crucial bearing on how we perceive that information. By contrast, creatives who hand over a script and stare at their shoes will not sell as many scripts.

This may sound like a lot of effort for the benefit of the account team, who after all aren’t the ultimate buyers of the work. But it’s worth it. The more you can get the account team to buy into your route, the harder they will sell it to the client.

Notice in the example above how clever Tom and Walt were in their preamble. When recapping the brief, they subtly highlighted the one aspect of it they addressed in their work.

This “reframing” of the brief is a fantastically useful maneuver. For planners, it’s essential, but it’s also a great skill for creatives to master. The principle is that, since few ideas are exactly 100 percent on brief, you slightly reframe the brief just before you present the work, so the work seems like it matches the brief more closely than it really does.

N.B. They haven’t handed over the script yet.

It really pays to literally start one sentence of your presentation with “The idea is...”

We creatives are experts at extracting the idea instantly from a script. Many account handlers and planners are too, but by no means all. However, they all know how crucial “the idea” is; so make sure you tell them what it is.

Sell, sell, sell, baby. One of the most successful commercials directors of the last 20 years—a guy called Tarsem—sold cars in L.A. to fund his way through film school. You don’t have to do that. But if you’re asking the team to commit the next six months of their lives to something, you should at least be able to tell them you’re excited about it.

And only now do they hand the script over. That’s right. A full two-and-a-half minutes of preamble. That’s not too much to ask, is it?

Even better than handing the script over—read it out, if you have acting skills. If it’s a print ad, talk them through the imagery. If it’s a digital idea, tell them what’s cool about it.

So to sum up, presenting to the team is really no big deal (although a lot of young creatives seem terrified of it). You just explain what the idea is, and why it’s on brief, and hand it over. But don’t wang on.

Should creatives present their work to the client? This is one of the most vexed questions in advertising. In some countries, such as the US, it is standard practice that creatives present their own work. In other countries, such as the UK, they almost never do. British creatives are stunned when they find out that American creatives do all the presenting. “So what do the account handlers do?” they ask.

If your agency has a firm policy on whether creatives present their work or not, then this section will be irrelevant to you, since you will be obliged to follow that policy.

However, in many countries, and in many agencies, the question remains unresolved.

There are agencies where some of the creatives present to clients and others don’t. There are agencies where the creatives present on certain accounts and not on others. It’s a gray zone.

But if you have the choice, what should you do?

IN FAVOR OF CREATIVES PRESENTING

The main argument in favor of presenting your own work is that the passion a creative shows can win a client over. As it’s your work, you’re going to be utterly convinced it is good, and conviction can be highly persuasive.

Not only will you feel more passionately about the work than an account handler can, but as it’s your idea, you’ll be able to bring it to life with more vividness and precision, which should mean a higher chance of a sale.

There’s even a theory that presenting your own work saves time, because you’ll be able to deal with any objections on the spot, rather than entering into a back-and-forth via the account handler.

And maybe you should ask yourself—if it’s not worth your time to take a cab across town and stand up for your work…are you sure it will be worth the next four months of your time that it will take to produce it?

BUILDING A RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CLIENT

Looking beyond this one sale, there’s a chance that by presenting directly to a client you can start to build a relationship with them that could prove fruitful for the future, and open a channel of communication that is clearer and more direct, because it’s not mediated through the filters of the account handlers and planners.

When you meet clients, you have to behave differently to how you behave within the agency—you have to understand that, to them at least, advertising is a serious business activity. James Cooper, creative director of Dare New York, complains:

“Too many creatives behave like it’s a game. They try to see how far they can take the game. In other words ‘What can we get away with—with the clients’ money?’ Short-term this is great fun, ‘Hey, it wasn’t a great ad but we got to go to Cape Town again,’ but long-term the client will think you are an immature idiot. The easiest way to get great work out is to form a proper long-term relationship with a client—do not assume that’s someone else’s job.”

You are certainly going to have to develop “client-facing” skills one day, when you become a creative director. That is why some believe that the sooner you meet clients, the better. There’s an argument that rank-and-file creatives are the most disposable individuals in an agency, because of their lack of client relationship. If a creative vanishes overnight (because the agency needs to reduce overheads), no client is any the wiser, whereas an agency has to think twice before getting rid of an account person or a planner, because they have to consider “the relationship.”

On the other hand, being able to present effusively has made the career of many a hack. We all know the type. They wax loudly and enthusiastically about the client’s product during meetings. They present awful scripts, with much bravado and theatricality—the hack is often a fine actor—scripts they swear will make the client “famous.” The client is blown away that anyone is that zealous about their product—far more zealous than they are themselves—and the hack quickly becomes their favorite creative and number-one go-to person.

And thus, a career is born. Albeit an undeserving one.

If your presentation skills exceed your talent, then maybe this is a valid path to pursue.

Despite what I have just said, I am a firm believer that creatives should not present their work to clients, if they have the choice.

Most account people are more charming and more articulate than most creatives. So why have the creatives do the presenting? It doesn’t make sense. I am a huge fan of getting people to do what they’re best at. You wouldn’t ask a striker to play in goal, would you? And if you’re appearing in court, you would want a professional advocate to put your case for you, rather than presenting it yourself, I am sure.

The account person knows the client better than you do, so may know better how to sell to him, and how to meet his objections—account handlers are experienced at resisting the onslaught of client comments. Whereas I’m told that it’s well known among account handlers that most creatives, when faced with client comments, simply fold up like sofa-beds.

Even the most useless account handler has an advantage when it comes to presenting work—the benefit of being an intermediary. It’s more believable when an intermediary pleads a case than when the plaintiff himself does it, because it looks less self-interested. Plus, it’s hard for a client to say directly to the person who had an idea: “I don’t like it.” Normally, and quite understandably, they will pretend they like it in the meeting, then call the account team a couple of days later and say: “Actually…I don’t like it.” So you will have wasted your time and theirs.

The time cost of presenting work can be a big factor, depending on how far away the client is based. Even a meeting with a client who is based just a few blocks away always seems to take half a day. Time you could be having ideas in. (Or surfing the internet.)

And the more time you spend with a client, the more you will get to know their business problems. That may sound healthy, but often isn’t. You can get bogged down in all their day-to-day concerns, all the internal stakeholders they have to please, and goals and sub-goals they have to meet. You’re a creative; you need to sit outside that. You need to have a general understanding of it all, and yet be aloof from it. How else can you give the client a fresh perspective?

BUCKING THE TREND?

In the last few years, the trend around the world has definitely been for creatives to spend more time presenting to clients. Some believe this is a change for the better. Personally, I don’t. Instead of spending their time where it’s most productive—generating wonderful original ideas—creatives are in meetings presenting to clients. We are doing what account people used to do so brilliantly.

Many creatives are not natural presenters—many are introverts, whereas you’d struggle to find an account handler who isn’t at the chattier end of the bell curve. I don’t see much benefit in asking the writer to stand up and sell, while the salesperson stays sitting down, and writes notes.

That’s why I believe that if you can avoid presenting to clients, you should do so.

However, if your agency has a policy that creatives present the creative work, then how should you go about doing it? The process of presenting to clients breaks down into two phases: “in the room,” and “before you go in the room.”

Before you go into the room, you should be marshaling the best reference you can. But don’t show too much. I have seen creatives present five separate pieces of reference for a single press ad, saying “this one’s a reference for the color palette but don’t look at the models, they aren’t right; for the models you need to look at this other piece of reference, but don’t look at the lighting on that one; for the lighting we have this other shot…” Most confusing. Keep the reference simple; find one or two pieces that say everything you want to say.

Rehearse with the account team what issues may come up. Rehearse your presentation as many times as you need to.

Make sure you know the names of the clients before you go in. People like to be called by their names. Make sure you know who does what, so you don’t ask their research manager a question about their TV budget, for example. And make sure you know who the key buyer is. Focus your energy on them, while not excluding the other people in the room.

IN THE ROOM

Once in the room, presenting to the client is much like presenting to the account team. Plenty of preamble is needed. Much of the set-up may be done by the planners and account handlers, but there may be some for you to do too.

For TV projects, you may need to make a mood film—a film made of clips from movies or other ads—which demonstrates your idea. For a print ad, bear in mind that the more finished your concept looks, the more the client will expect their finished ad to look exactly like that. So you’re in danger of creating a straitjacket for yourself.

“I get around this by drawing the concept very roughly, then blowing it up big so it looks more impressive than just a scribble,” says Paul Belford, one of the UK’s most awarded art directors. “I get the client to buy the concept first; and only then do I show reference material.”

Don’t treat any of this lightly, thinking that your “real job” is to come up with the ideas. The most successful creatives aren’t just the ones who are good at coming up with ideas; they’re good at selling them too.

“When a great showman like Alex Bogusky walks into a room...well, clients can get a little star-struck,” says John January, executive creative director of Sullivan Higdon & Sink, Kansas City. “Clients will tell you time again that a strong strategic process is what wins business. But this is a justification. They still love a good show. Would we have it any other way?”

PRESENTATION TIPS

· Keep reference simple

· Rehearse with the account team

· Get your set-up right

· Show your conviction

CONVICTION CONVINCES

“How to sell an advertising idea” could be an entire book in itself, so I’ll restrict myself to just one main point: nothing convinces more than conviction.

When a client looks at a concept, they can tell if it’s communicating the wrong message, or if the tone is wrong for their brand. But if nothing is wrong with the ad, and they begin to suspect it may be “right,” the question becomes “how right.” And a huge factor that can sway them here is your conviction. You have to tell them this ad is going to be great.

Creatives are often accused of being arrogant, and of “talking up” their own work. Well, you have to. Whether your ad gets made or not may depend on how much you believe in it.

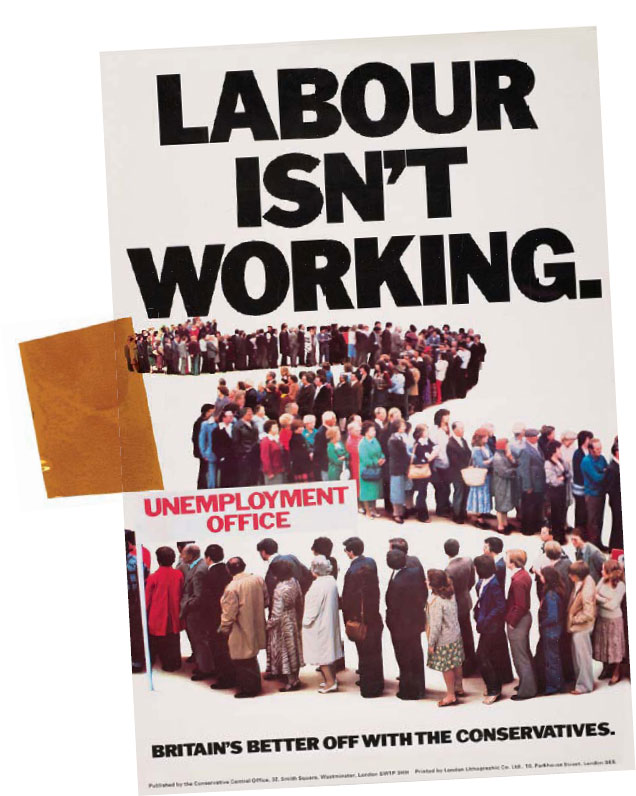

Perhaps the UK’s most famous poster is “Labour Isn’t Working,” by Saatchi & Saatchi for the Conservative Party in 1979. Those three words, above a shot of people queuing at an unemployment office, became a significant factor in Margaret Thatcher’s first election victory.

However, what is less well known is that when the concept was first presented to Mrs Thatcher, she didn’t like it. “This poster advertises Labour,” she told Maurice Saatchi. “On the contrary, Margaret,” he replied. “It demolishes them.”

One of the reasons I particularly like this story is that I just love the word “demolishes.” But the real lesson here is Maurice Saatchi’s conviction.

“Labour Isn’t Working” poster by Saatchi & Saatchi

THE TOP TEN OBJECTIONS YOU WILL HEAR AND HOW TO GET AROUND THEM

In my opinion, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with showing the negative. What did Volkswagen’s famous “If only everything was as reliable as a Volkswagen” campaign show? A negative—unreliability. Another example—the amazing viral ad in which a baby shoots out of the womb and flies through the air, ageing from young man, to middle-aged man, to old man, before plunging headlong into a grave just 60 seconds later, thus demonstrating the ultimate negative—that life is short (it’s an ad for Xbox, tagline: “Play more.”)

If someone levels the “showing the negative” accusation at you, try the above examples. However, I’ve noticed that when people do like an ad that shows the negative, they use different language to describe it—they call it a “problem-solution” ad, or say that it’s “demonstrating the need for the product.” They normally only make the complaint that it’s “showing the negative” if there’s some other reason they don’t like it, which they can’t articulate. It’s worth trying to find out what that reason is.

To get around this objection, you need to argue that the brief was an excellent battle plan, which was believed to be the best way to achieve the client’s objective, but if your work achieves that objective in a different way, then surely it doesn’t matter whether it follows the plan. The true goal is to win the war, not to follow the battle orders. In summary, you need to argue that the work you are proposing will create the desired output, even though it may not be based on the agreed input.

This objection is best anticipated and dealt with in advance, because it’s quite difficult to get people to see a joke in an entirely new way when they’ve heard it once in a certain style.

The truth is that tone is easy to manipulate. For example, I have seen a sexist and vulgar sketch from the Benny Hill Show turned into a classy and romantic commercial for a mobile phone network. The creator of this multi-award-winning commercial was clever, and anticipated that a Benny Hill gag could be rejected for being “wrong tone.” So he was careful when writing the script that it didn’t read like a Benny Hill gag, and he never showed the Benny Hill sketch as a reference.

If you haven’t dealt with the “wrong tone” complaint in advance, you can still get around it, but you will need to do a complete rewrite of the script, or redraw of the concept, and provide entirely new reference.

In the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, one of the most memorable gags is that the knights “gallop” on foot, while clapping coconut halves together to simulate the noise of horses’ hooves. But that wasn’t the original plan. Before filming began, the budget was cut, and there was no longer enough money for horses.

So if someone tells you there isn’t enough money for your project, take a closer look and see if there are any “horses” you can cut. Since simpler is always better, and often funnier, this objection may even improve your idea.

The reality is that every idea has been done before, in some form or other. And no creative director is really expecting that what you show him will be wholly dissimilar from any piece of communication previously produced on planet Earth. He just wants to see things that feel fresh.

You may be able to get around his objection by changing the execution of your idea, so it appears radically different to anything that has gone before. Or try removing the most familiar elements of your idea, and placing a bigger emphasis on the less familiar parts. If a story is well known, try looking at what happens before the story, or after it. If an object is over-familiar, try looking at it from a different angle. In advertising, we’re often saying something that’s been said before. But that needn’t matter, if you can find a fresh way of saying it.

The first of those is easy to get around—you just have to show how your idea does adapt, by coming up with some executions in different media. An idea is an abstract concept that is not dependent on the medium it’s expressed in, so if you do have a genuine idea, this should be possible. If it proves difficult, write your idea down purely as a set of words, not an ad. From there, it should be possible to “stretch” it.

In general, when dealing with an objection, make sure that you treat it as a genuine issue. Never reject a comment out of hand, just because it conflicts with your original vision. After all, what if it’s an improvement? Advertising is very much a collaborative process, and over the course of your career you will work with many brilliant planners, creative directors, account handlers, and yes, even clients, all of whom have a legitimate role to play, and all of whom will make your work better, from time to time. And even if you’re convinced that an objection is invalid or damaging, don’t dismiss it over-harshly or over-swiftly, as the person who made it could become riled, and the objection could become personal.

On the other hand, if you sense that an objection is completely invalid, not strongly held, or just being raised as a protest, then ignore it. It could go away.

There are times when fighting an objection just makes the other person more entrenched in their position.

If you know that your solution is right, then sometimes the smart thing to do is wait. Let them explore other options for a while. When these don’t work, they will come back to yours. Many, many good ideas didn’t get bought the first time round. Just make sure you have the idea saved on your hard drive. Its time will come.

Finally, bear in mind that obstinacy should be a tactic, not a way of life.

Jamie Barrett, ECD at Goodby Silverstein, San Francisco says that;

“Too many people confuse obstinacy with creative integrity. A good creative person has to be willing to find greatness in what is sometimes an extremely small area. What is the coolest idea you can possibly come up with? What will the client actually buy? Where do those two things intersect? That’s the hardest thing for a creative person to learn, and ultimately what separates the best from the rest.”

GETTING STUFF READY FOR RESEARCH

One of the most important stages in selling your work is getting it through research.

Creatives generally have one of two feelings about research—they either fear it, or hate it.

There is a myth that “in the old days” nothing was researched. Supposedly, clients had the balls to buy brave work, without stopping to worry what opinion consumers might have of it.

I don’t believe this for a minute.

Of course, there were brave clients in the past. John Meszaros, a legendary chief marketer at Audi in the UK, famously never used a focus group in his life. When an account man once asked if he wanted to research one of the agency’s ideas, Meszaros replied: “Are you saying my judgement’s no good?”

But there are brave clients today also. Clients who understand that breakthrough work doesn’t play well in groups.

However, they’re in the minority. Most clients prefer to research ideas before they will approve them. Highly finished visuals will be created to research a print concept. For a TV commercial, they will ask the agency to prepare storyboards, sometimes accompanied by a “narrative” that is either read out to consumers by the researcher, or recorded in advance by a voiceover artist. Sometimes the storyboards are filmed, with added sound effects and camera moves, to create what’s called an “animatic.”

RESEARCH HORROR STORIES

The way most creatives deal with research…is to complain about it. They explain to the account man in great detail how research groups are an artificial environment, how participants in groups don’t tell the truth, how they are easily influenced by the one loudmouth you always get in the bunch, and how some of the world’s best-loved campaigns—such as “Heineken refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach”—were roundly rejected when put in front of focus groups.

They tell horror stories about how consumers in research groups are asked to move a joystick up and down to indicate how much they are enjoying a commercial. And they laugh about the “cheesy” ads, which they claim are the only ones that do well in research.

Some creatives even go so far as to make humorous films, deriding what happens in research. In the most famous example, which you can find by typing “1984 focus group” into YouTube, a group of consumers who have never seen Apple’s “1984” are exposed to the storyboards, and complain that it is “bizarre, creepy, drab, and depressing.” They then suggest all manner of embarrassing “improvements,” such as adding brighter colors, animals, or even having the stormtroopers break into freestyle dance moves.

Anyway, here is an important newsflash: research is not going away.

However right or wrong, good or bad, flawed, embarrassing and wrong-headed the research game may be, it is here to stay.

Therefore, the smart creative learns how to win at it.

HOW TO BEAT THE RESEARCH PROCESS

The first principle to bear in mind, if you want to get your idea through research, is that you need to make it much more obvious than you think you do.

Bill Bernbach once said: “How do you storyboard a smile?” He was right. You can’t communicate the full emotional impact of a smile on a real human face, in a drawing. Therefore, you are going to have to exaggerate it. When you brief the storyboard company, instruct them to make that smile the biggest, widest, whitest-teeth smile they’ve ever drawn.

I was once amazed to see an animatic made by a wily team at DDB London, for a Marmite commercial. The script concerned a (male) lifeguard who goes to the aid of a (male) bather and, when administering the kiss-of-life, gets drawn into a full-on snog, because the bather is enraptured by his Marmitey breath. In the script, and indeed in the final commercial, the kiss washandled with subtlety. But in the animatic…a cartoony pair of pouting lips, planting themselves repeatedly on the other guy’s lips—backward and forward, at least eight times—accompanied by the cheesiest smooching sound-effect I had ever heard.

I learned a big lesson that day. You may want your ad to be subtle and clever. But your animatic shouldn’t be. Your animatic needs to be simple and obvious.

The animatic is not what is going to run. You will not be made to stick to the tone of it—everyone understands that it’s basically a cartoon. So cheat. Make the idea clearer than a windowpane in bright sunlight.

Cheat with the narrative as well.

It isn’t good writing to have your script say: “Sally is

cross with Jim, because he’s stolen her yogurt from the fridge.” You’re supposed to write only what you can shoot. However, for research, you should forget all about good writing. If it helps to say: “Sally is cross with Jim, because he’s clearly enjoying the deliciousness of her yogurt, savoring its fruity taste and obvious health benefits,” then write it.

A final note about research. The UK’s finest-ever creative, John Webster, was a huge fan of it.

He wanted people to like his ads.

He would engage fully with the research process, and chat extensively to the planners and researchers. His idea was to use research for his benefit. He believed that if used in the right way, research could improve his ideas, not destroy them.

For example, when he created the character of the Hofmeister bear for Hofmeister lager, he insisted that the researchers shouldn’t ask people whether it made sense for a bear to talk, or endorse this particular brand of lager. Instead, he had them ask questions like “Which of these outfits do you see the bear wearing?” and “What kind of accent should the bear have?” He presented the bear as a fact, while everything else was negotiable.

During research, the Hofmeister bear duly evolved from John’s original conception of a suave James Bond-esque bear in a dinner jacket, to a gruff working-class bear in a baseball jacket.

And if a few people in research groups helped determine what the bear was going to wear, then so what?

John got his bear.

One day, a creative director was asked to do some training for the agency’s account handlers. So he had them spend the morning making a model airplane. Then, at lunchtime, he reviewed their work. He took each plane in his hand and crushed it to pieces. “That,” he said, “is what it feels like to be a creative.”

The story probably isn’t true, but it does illustrate one of the harder aspects of the creative’s job—daily rejection of our work.

WHY REJECTION IS SO PAINFUL FOR CREATIVES

There are several reasons why the rejection we face is so painful.

First of all, it’s so frequent. As I mentioned in Chapter 1, you will probably find that at least 99 percent of all the ideas you ever have will be rejected.

It’s a brutal kind of rejection too. Many ad ideas contain something of the creator—they might be based on a childhood memory, or a scene from your favorite movie. So the rejection can feel very personal. Creatives often refer to their “babies being killed.” A little harsh perhaps, but the analogy to another personal creation has some validity.

Few other professions face the brutality of failure we do. As David Droga once put it: “If I were a surgeon, and nine out of ten of my patients died, I would seriously question whether I should be in the industry.” But for us, that kind of failure is normal.

Or compare with the job a builder has—every single brick he lays becomes part of a house. At the end of each day, he has the satisfaction of having built something solid and tangible. But a creative may spend all day working on ideas that get rejected, and at the end of the day have nothing at all to show for his labors.

Sometimes, entire months can be wasted. And it may be through no fault of the team’s. Projects can get shelved for all kinds of reasons.

Unfortunately, there is no way around the problem of rejection, only better ways of dealing with it.

VIEWING REJECTION IN A POSITIVE LIGHT

There are some creatives who have an amazing ability to view our 99 percent rejection rate as a positive. The thinking goes something like this: since every time an idea is rejected, an accompanying reason is given, it’s possible to view each new rejection as a new piece of information about the brief. Or about the taste of the person issuing the rejection. Your CD was once bitten by an orang-utan and will not countenance any primate-based TV ads? That’s a good learning.

According to this theory, each rejection is valuable, and is actually bringing you a step closer to success.

It’s also vital you don’t see the rejection as a rejection of yourself, however personal the work is to you. Remember that the rejector has no clue of your autobiographical inspiration; they’re purely reacting to the piece of paper they see in front of them. And if they reject a route based on a piece of music or an artist who is significant to you, they’re not criticizing your taste, they’re just saying that your choice isn’t right for this brief.

Sometimes it’s worth sharing the pain with another team, or a trusted friend. If the friend doesn’t think much of your idea, then you realize you haven’t lost much anyway. And if the friend thinks it was brilliant, then at least you will get a lot of sympathy.

There are some practical steps you can take to minimize the pain of rejection. Immediately after a negative meeting or review, ensure you have some time alone with your partner to fully curse the account team/ client/creative director. You shouldn’t feel bad about doing this. You don’t even really mean it. It’s just a letting off of steam.

However, after you’ve comprehensively ridiculed the account team/client/creative director, you must be careful not to turn the gun on yourself. It’s tempting to follow a slagging-off session with a sulk. We all like to wallow in sadness sometimes, but in a professional context, it’s not helpful. The initial anger that follows the rejection is helpful, I believe, because it releases frustration. But sulking is bad, because you can get sucked into a downward spiral, when what you need to do is move forward.

Sitting there feeling sad because the world doesn’t recognize your genius is not going to make you happy. Only getting the world to recognize your genius will. And for that, you need an ad that does get bought. So don’t sulk. You should rant, clear your head, and then get back to work.

Your first job is to work out how total this rejection is. They’ve said no to your idea, but did they reject the whole thing, or is there one bit of it you can salvage? Or build on? What new ideas can emerge, like a phoenix from the ashes?

If the rejection is total, you can console yourself with the thought that it may not be final. Right now, they’ve said no to your idea. But you may be able to bring it back later, when the brief still hasn’t been cracked, and they’re desperate.

And although your idea may not be right for the brief as it stands…the brief can often change. I know of a creative who had a TV ad made fully seven years after he first presented the script. When he first wrote the ad, the tone of the idea was wrong for that brand. But over time, the brand’s tone evolved and, eventually, his script became right.

So put your rejected work in the bottom drawer.

A good idea never dies. It just sits in limbo, like a lost soul, waiting for the right body.