chapter SIX

Financial Needs and Fundraising Strategies

Organizations have three financial needs: the money they need to operate every year, not surprisingly called annual needs; the money they need to buy or improve their building or purchase or upgrade equipment needed to do their work, called capital needs; and a permanent income stream to ensure financial stability and assist long‐term planning, the source of which is an endowment or a reserve fund or sometimes both.

ANNUAL NEEDS

Most organizations spend most of their time raising money for the program needs of the current year. This kind of fundraising is often referred to as the “annual fund” or the “annual drive” or, to cover all tracks, the “annual fund drive.” Raising money for the annual fund involves several strategies, such as online fundraising, direct mail, special events, phoning, and personal visits, all of which are covered in Part Three. The purposes of annual fund strategies are to acquire new donors and to encourage current donors to give again and, if possible, to give bigger gifts.

Because the overall goal of fundraising is to build a base of donors who give you money every year, it is helpful to analyze how people become donors to an organization and how, ideally, they increase their loyalty to the nonprofit and express that increased loyalty with a steady increase in giving, as they are able. Organizations working for social change (ending violence against women, dismantling white supremacy, creating humane immigration policies), where the result of the work we are doing may not happen for years or even decades, must pay particular attention to building donor loyalty and to helping donors understand the long‐term nature of social justice work.

As donors move from having never given to a particular group to giving regularly year after year and sometimes several times a year, they go through three phases. The first phase starts when a donor is asked to give to an organization they have heard or read about, or have been solicited for by a friend, and decides on the spur of the moment to make a donation. That first gift is called an “impulse gift.” Even if an impulse gift is fairly large, it will rarely reflect what the donor could really afford, and it is generally based on the donor having little knowledge about the organization. Once the gift is made, the donor is thanked as soon as possible; then the donor is asked to give again several more times over the next year in a few different ways, such as by phone, at an event, or with a personal email or letter.

If the donor continues to give regularly for several years, that person becomes what is called a “habitual donor.” Habitual donors see themselves as part of the organization and identify with the work and the victories of the organization. Some habitual donors have a bigger commitment to the organization than their gifts reflect and should be asked for a larger gift. Identifying who these donors are and asking them to increase their gifts forms the basis of an upgrade program; that process is often the majority of the work the organization will do to secure what are known as major gifts—that is, donations above a threshold at which most of the organization's donors are not giving. In addition, many habitual donors may express their commitment to the organization through a gift made through their estate plan.

Once donors are giving larger gifts than they give to the other nonprofits they support, they become “thoughtful donors.” Instead of just giving what they are in the habit of giving, they now think about whether the size of their gift adequately reflects how much they care about the organization's work relative to what they can afford.

The process of moving people from nondonor to donor, then to habitual donor, and then to thoughtful donor is the main focus in planning annual fund strategies. To maintain its annual income, an organization must recruit a certain number of new donors every year, make sure the majority of their current donors give again, upgrade a certain number of regular donors to become major donors, and invite as many donors as is appropriate to help with extra donations for special projects or to attend events.

Asking Several Times a Year

Often people will say they dislike receiving several appeals a year from organizations, and they rightly assume that they are not alone. Even though it is counterintuitive, asking several times a year actually works. There are several things to keep in mind about this reaction, along with anything else donors tell you that they like and don't like. The most important has ramifications for all fundraising: just because one donor doesn't like something (such as being asked several times a year), it doesn't mean that most donors feel the same. The fact is that most people don't even notice how often they are asked, particularly if you are using a few different strategies to ask them.

Some donors even give every time they are asked. Asking multiple times a year works because people have ups and downs in cash flow. For example, perhaps Maria gets an email appeal from a favorite organization the same day she learns her car needs new brakes. She deletes the appeal. Then Maria gets another appeal the same week that she gets an income tax refund; she decides to share her good fortune and promptly clicks on the donate button.

Different people like different approaches to giving. For example, one person is invited to attend a premier of a movie related to the issue the organization works on and immediately sends it to three friends, suggesting they all go together and have dinner after. Another donor thinks, “What a waste of money to rent a theater when they could just tell people to stream it.”

Fundraising is a process of building relationships. When it is possible and relatively easy to do so, try to accommodate your donors. If a donor tells you, “I only give once a year, so please only ask me once a year,” then go into your database and suppress that person's name for any extra appeals. If a donor says, “Don't ever try to reach me by phone,” note in your database not to call that person.

Attracting New Donors

Between 20% and 30% of first‐time donors make a second gift, and about 65–75% of donors who have given more than once continue to give. The hard truth is that most people, when offered the chance to donate to your organization, say no, and even those who make one gift do not make a second gift. Simply put, this means that if 1,500 people made a donation last year, not more than 1,000 of them will give again this year, so you will have to attract 500 new donors just to maintain the number of donors you had at the beginning of the year. In planning fundraising strategies, then, you need a few strategies focused solely on attracting new donors.

On the other hand, organizations that lose fewer than one‐third of their donor base most likely do not have enough donors—almost any organization can keep a small group of donors renewing year in and year out. You want to grow big enough that you are bringing in a lot of new donors, knowing that up to one‐third of them will not stay. Organizations that lose more than one‐third of their donors are not doing enough to keep them; in the case of most grassroots organizations, this situation usually means they are not asking donors for money often enough or thanking them when they do give. (The exception to this is when your organization is in the news with an emergency or a pressing issue. You may then attract a number of new donors who will not give again.) Remember, people who give away money are being asked often: the organizations they give to may ask several times a year, and they are also being solicited by organizations to which they haven't given. If you only ask once a year, yours becomes a minuscule percentage of the solicitations the donor receives. In fact, many lapsed donors report that they don't remember receiving any requests from the organization, and that it was not their intent to stop giving. To retain your donors, you need to use a few strategies designed just for them.

Finally, you need to have some strategies to persuade current donors to give bigger gifts, not just additional gifts—these are called upgrading strategies. Part Three of this book discusses a wide variety of donor acquisition, retention, and upgrading strategies and their uses.

CAPITAL NEEDS

Occasionally, organizations need to raise extra money for capital purchases or improvements. Capital needs can range from new computers to the cost of buying and refurbishing an entire building. A capital expense is a one‐time or infrequent expense that is too large for the annual budget. Most donors who give capital gifts have given thoughtfully to an annual fund. They know your organization, they believe in your cause, and they have the resources to help you with a special gift. These resources could be stocks, bonds, real estate, or any one‐time or infrequent source of income, such as a bonus or a lottery prize. (Many people used their COVID stimulus checks to make one‐time gifts.) These gifts are given only a few times in a donor's lifetime, and they are usually requested in person. (See Chapter Twenty‐Six, “Raising Money for Capital.”)

ENDOWMENT AND RESERVE FUNDS

An endowment fund is a glorified savings account in which an organization invests money and uses the interest from that investment to augment its annual budget; the invested amount, or principal, is not spent. Endowment funds are raised in many ways, but the traditional source is legacy gifts, such as bequests. A gift from a person's estate is in some ways the most thoughtful gift of all and usually reflects a deep and abiding commitment to an organization. It also reflects the donor's belief that the organization will continue to exist and do important work long after the donor is dead. Most often, a person making such a gift has a personal relationship with the organization. The idea of making an endowment gift can be introduced to donors in a variety of ways.

A reserve fund is a way to set aside funds that may be needed in times of emergency. Organizations that hope that someday their work will no longer be needed (which is what most social change groups are working toward) may recognize that an endowment may not be necessary for them, but a reserve fund allows you to put money aside, use the interest, and occasionally use the principal. (How to set up an endowment is discussed in Chapter Twenty‐Four, “Setting Up an Endowment,” and “Endowment Campaigns” are discussed in Chapter Twenty‐Seven.)

THREE GOALS FOR EVERY DONOR

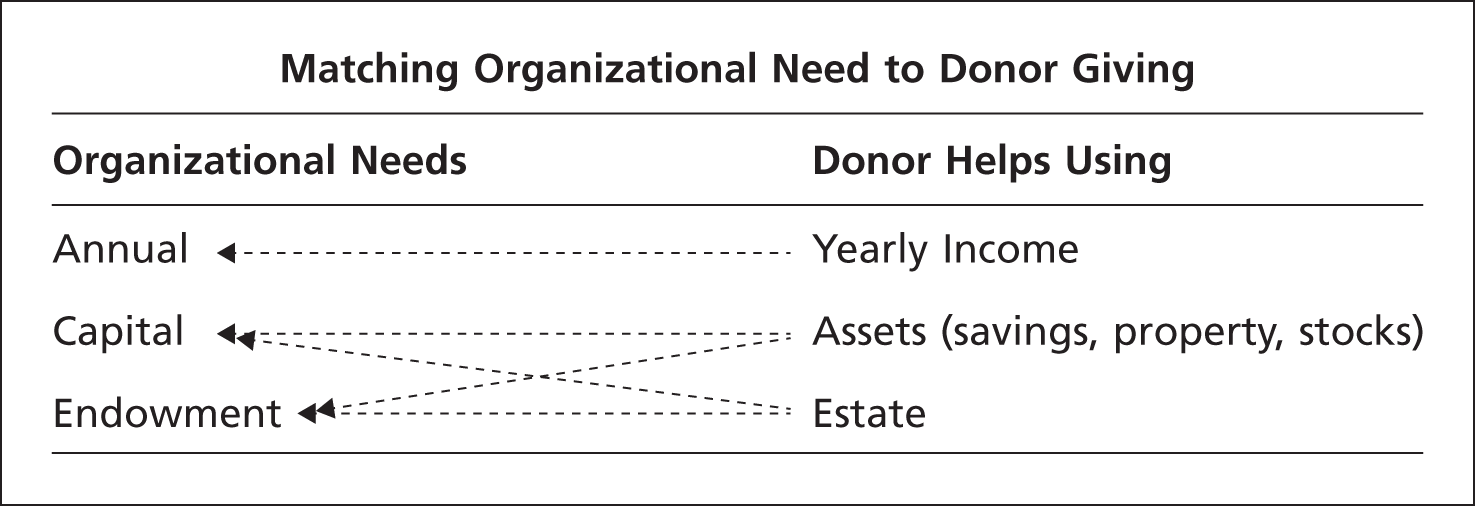

An organization has three goals for every donor. The first is for the donor to reach the point of being a thoughtful donor—to give the biggest gift they can afford on a yearly basis. Annual gifts usually come from the donor's annual income. The second goal is for as many donors as possible to give gifts to a capital or other special campaign. These gifts do not have to be connected to capital improvements, but they are gifts that are unusual in some way and, because they are usually substantial, are only given a few times (or possibly only once) during the donor's lifetime. Capital gifts are usually given from the donor's assets, such as savings, inheritance, or property. A donor cannot afford to give assets every year, so will only give such a gift for a special purpose. The third goal is for all donors to remember the organization in their wills or to make some kind of arrangement benefiting the organization through their estate plans. An estate gift is arranged during the donor's lifetime but fully received by the organization on the donor's death. Obviously, these gifts are made only once.

Most small organizations will do well if they can plan a broad range of strategies to acquire, maintain, and upgrade annual gifts, but over time organizations need to think about capital and endowment gifts and learn to use fundraising strategies that will encourage such gifts (see the following chart).

THREE TYPES OF STRATEGIES

Because all strategies are directed toward building relationships with funding sources—whether these sources are individuals, as this book stresses, or foundations, corporations, or government—it is important to understand the types of strategies that create or improve relationships with donors. There are three broad categories of strategies—acquisition, retention, and upgrade—that directly relate to the cycles that donors follow: giving impulsively, giving habitually, and giving thoughtfully. Ways to choose and implement specific fundraising techniques for each kind of strategy are described in detail in Parts Two and Three of this book.

Acquisition Strategies

The main purpose of acquisition strategies is to invite people to give to your organization for the first time. Online appeals, crowdfunding, direct mail, or some kinds of special events are the most common acquisition strategies. Acquisition strategies seek impulse donors, and the income from them is generally used for the organization's annual fund. The main goal of getting donors to give for the first time is to be able to ask them for a second gift. The income from the first gift is rarely significant, and the cost of soliciting the gift may be as much as or more than the gift itself (see Chapter Fourteen, “Direct Mail,” for why this is the case).

Retention Strategies

Retention strategies seek to persuade donors to give a second time, a third time, and so on, until they are habitual donors. The income from retention strategies is also used for annual needs. Donors who give small gifts regularly are the bread and butter of individual donor programs and are as important as donors who give very large gifts. During the Great Recession of 2007–2010, organizations that had a broad base of individual donors often did not have to make budget cuts, whereas those that had focused much more on major gifts or foundation grants saw their income decline, sometimes precipitously. Stocks crashed, which meant that foundations and many wealthy donors had less to give. People who remained employed, which was the majority of people even at the height of the recession, continued to give. Organizations discovered that financial security comes from a lot of donors giving what they can rather than a few donors or funders giving a lot.

Upgrading Strategies

Upgrading strategies aim to get donors to give more than they have given previously—to give a bigger gift regularly, and later to give gifts of assets and a gift through their estates. Upgrading is done almost entirely through personal solicitation, although it can be augmented by email, mail, or phone contact or through certain special events. Upgrading strategies seek to move habitual donors to being thoughtful donors. The income from thoughtful donors is used for annual, capital, and endowment needs, depending on the nature of the gift or the campaign for which the gift was sought.

As you create a fundraising plan, choose strategies that correspond to your goals for acquiring, retaining, or upgrading donors. (See Chapter Thirty, “Creating a Fundraising Plan.”)

PLANNING IS TIME WELL SPENT

For small organizations, the ultimate reason to be thoughtful about fundraising strategies is to work smarter, not harder. The organization in the house party example raised 400% more money in the second year by spending a little more time to think about the strategy more thoroughly. There is a saying from classical Latin, “Festina lente” or “Make haste slowly.” This adage applies to fundraising—and especially to the fundraising programs of small organizations with tight budgets and little room for errors that result from carelessness and lack of thought. You can put time in on the front end, planning and doing things right; or you can “save time” on the front end, only to have to spend time during the middle of fundraising efforts trying to fix what is not working and calm frustrated volunteers and board members. This book will help you be a front‐end time user!