Markets, Part II: The Nontraditional Film

Rules are made to be broken.

PROVERB

I couldn’t decide what to call this chapter. Suggestions included Son of the Markets, Specialized Markets, When Your Film Is Different, One Size Does Not Fit All (my personal favorite), and A Special Film Deserves Special Handling (my assistant, Faryl’s, favorite). Finally, at the behest of my editor, I settled on The Nontraditional Film.

The problem is that this chapter describes a variety of formats. Documentaries and large format films have both theatrical and nontheatrical components, while direct-to-DVD and downloading to the Internet and cell phones do not. Since the business models for these formats tend to differ from that of the fiction feature film, I am going to discuss each here.

Documentaries

Documentary films have entered the mainstream. Throughout the 1990s, they gained a prominence on the theatrical screen. The story of the first five and a half years of the 21st Century was that more and more documentaries were given a chance at the theatrical box office. 2004 was declared the “the year of the documentary” by critics and analysts. Rather than being a fluke or tied only to the presidential election, nonfiction films have continued to draw audiences. Many of them find money from nonprofit sources and always will. With the apparent marketplace success of docs, though, it has become essential to write business plans for equity investors, also.

Markets

The target markets for documentaries are the same as those for fiction films, save one group. Documentary audiences themselves are the first target audience to list. There are enough films with high public awareness to give as examples. Then there is the substantial television audience for documentaries, which Nielsen Media Research has estimated at 85 percent of U.S. television households. Rather than waiting for television rollouts, the audience is going to see them in movie theaters first. Their attendance figures also have increased the value of docs to the video/DVD buyers and television programmers. In addition, analysts suggest that reality television has helped documentary films find their growing theatrical audience.

The rest of the market section is the same as that for fiction films. Every documentary has a subject, be it political, economic, inspirational, historic, sports-related, etc. These market segments often can be quantified or at least described. Fiction films with the same genres or themes can be used as examples in the market section as well, although they can’t be used as comparatives for forecasting.

Forecasting Is Different

Until 2002, I hadn’t written any business plans for documentaries. The reason is simple: There weren’t enough theatrical docs that had earned significant revenues worth talking about. The success of Roger and Me in 1989 began the reemergence of the nonfiction film as a credible theatrical release. After a few successful films in the intervening years, 1994’s Hoop Dreams attracted a lot of attention by reaching U.S. boxoffice receipts of $7.8 million on a budget of $800,000. The same year, Crumb reached a total of $3 million on a budget of $300,000. In 1997, a Best Documentary Oscar nominee, Buena Vista Social Club, made for $1.5 million and grossing $6.9 million, scored at the box office and with a best-selling soundtrack album.

Michael Moore’s 2002 Bowling for Columbine raised the bar for documentaries by winning the Oscar for Best Feature Documentary and the Special 55th Anniversary Award at Cannes, and by earning $114.5 million worldwide. The same year, Dogtown and the Z-Boys, The Kid Stays in the Picture, I’m Trying to Break Your Heart, and Standing in the Shadows of Motown all made a splash at the box office. The success of these releases was not anything like Columbine, which had a political and social message, but was noticeable nevertheless. In 2003, Spellbound seemed to confound the forecasters by drawing a significant audience, as did Step into Liquid, The Fog of War, and My Architect. The following year, 2004, Michael Moore surprisingly—and convincingly—bettered his own record with Fahrenheit 911, which was made for $6 million and earned more than $300 million worldwide. Distributors found more documentaries that they liked: Riding Giants, The Corporation, Touching the Void, and the little doc that could, Super Size Me (made for almost nothing and earning $35.2 million at the box office). In 2005, there was the popular Mad Hot Ballroom, Enron: The Smartest Guys in Town, and Why We Fight.

For some of these documentaries we know the budgets and for some of them we don’t. Some have worldwide distribution and some don’t. Therein lies the first problem of writing a business plan around a documentary film. However, it is far more doable now due to the number of films that have been released. There are other factors that make documentaries different from fiction films. First and foremost, there are fewer of them. Also significant is how widely their subject matters vary—comparing two documentaries to each other can still be a case of comparing apples and oranges.

The Method

Due to the limited number of films and the lack of some information, I break my own rules in forecasting docs. There is more responsibility placed on you, the filmmaker, to be sensible and logical throughout the process. I know that many of you would rather never think about numbers. However, your investors do. How you do a forecast has to look rational to them.

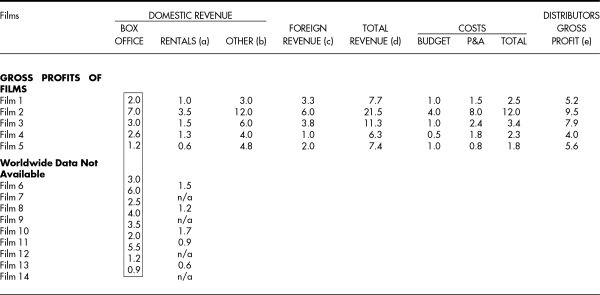

Take a moment to review the financial section of the CD accompanying this book. For your convenience, print Tables 1 and 2 for reference while reading this section.

Table 1 lists the worldwide data for films arranged by the three most recent years for which worldwide numbers are available. For example, Table 1 includes films from 2002 through 2004 with the films separated by years. Table 2 lists the North American box office and budgets only for films from the two most recent years, 2005 and 2006, as it generally takes two years to be able to get the complete domestic ancillary and foreign numbers for films. I didn’t include a traditional film business plan in the comparison tables unless I knew the budget.

We don’t know the budgets for quite a few documentary films. Reason number 1 given by many documentary filmmakers is that they have made the film over a long period of time and don’t know the actual budget. It is true that many are made of a combination of cash from grantors and in-kind contributions, so it may be hard to know the real number. Or, reason number 2, they choose not to tell us. With the far fewer number of docs in the theatrical marketplace, we have no choice but to use those films, anyway. Therefore, I normally list all the films that have worldwide numbers first, but without dividing them by the years of their release (see Table 6.1 at the end of the chapter); I list the films without worldwide numbers in a separate heading underneath, showing only box office and rentals. When rentals are not available for more recent films, I enter “n/a.” You can also list budgets for these films; however, my experience has been that because so few of the budget numbers for these films are available, trying to include any just makes the table confusing.

Which documentaries to use and which not to use is a choice you will have to make. Clearly, political films don’t fit with a sports or music documentary. They reach a broader audience, particularly with all the turmoil that has been going on around the world. I can’t give you a hard-and-fast rule for which documentaries to use; it has to be your choice.

As when making a table of the traditional films, list the extraordinary films when they are appropriate (e.g., Fahrenheit 911, March of the Penguins), but do not include them in your forecasting process. (See the note on CD Table 2.) Even though it is tempting to use their high revenues, remember that your investor probably will know better. You want him to have confidence in you.

Note that fiction films cannot be mixed into a forecast for a documentary. They have a wider audience appeal and usually wider distribution. All of the revenue windows for a fiction feature are going to show higher grosses. Using them would mean that you are fooling not only your investor with an unlikely net profit number, but yourself as well.

Next, go through the forecasting process in the CD’s financial section. It’s not necessary to repeat all those instructions here. Apply that process to your films with worldwide numbers. Taking into account those results and what you know about the box office results for the other documentaries, make a reasoned estimate of the box office for your film. Then forecast the rest of the dollars.

Television Documentaries

As of June 15, 2006, the Internet Movie Database lists 53,766 documentaries. The majority of those are television series or features. Generally, they are financed directly by the broadcast/cable networks.

Except for the public television networks, documentaries are not a staple of broadcast television. Broadcast television relies on larger audiences than documentaries typically attract. PBS does finance some documentaries, normally at budgets less than $500,000. For them, it is the project that is important. While it is true that in recent years PBS has sent these films to film festivals and even put some into theatrical distribution, the PBS station responsible for funding a particular doc normally controls all the rights and the revenues. In addition, it is still a modest part of their yearly budget, so the funds available are limited.

A large number of cable and premium channels also finance documentaries, and they occasionally buy completed films. In a sense, however, this is the same as getting a license fee from the broadcast networks. The budgets can range from below $100,000 to over $1 million, depending on the cabler. In addition, there has been a surge in digital channels across Europe, which has made the demand for docs of all genres greater, according to Daily Variety.

If you were to make a documentary and then try to sell it to one of these outlets, there is reportedly little payment beyond the cost of the doc. There is no database to use for doing the forecasting section of this type of business plan.

Both theatrical and nontheatrical documentaries are financed by not-for-profit grants and other funding. Although some of the information that you would use in this book’s business plan format would be useful in a grant application, you cannot write one business plan to send to all grantors. Each of these organizations has limited resources and specific subjects that it will fund. Of course, many will not fund films. You have to do your own research to find an organization whose goals your subject matches.

Often docs, or even fiction films, are made with a combination of equity funding and grant money. In that case, you will have to both have a “standard” business plan for the equity investors and make a separate grant application. In fact, when I put “filmmaking grants” into a search engine, an article about one of my client’s films appeared. He has a documentary that also appeals to religious groups that provide funding.

There are numerous books about raising grant money. For filmmakers, though, I always recommend Morrie Warshawski’s books (see Chapter 9).

Large-Format Films

Large-format films are made by several companies, among which are the IMAX corporation, studios, and independent producers. Since the industry started in 1970 at EXPO ’70 in Osaka, Japan, when IMAX Corporation of Canada, introduced “the IMAX® Experience” at the Fuji Pavilion, the films tend to be referred to by that manufacturer’s name. As of December 2005, there were 390 large-format theaters worldwide, with 214 in North America. Sixty-four theaters worldwide were commercial standalone, 93 were in multiplexes, 25 were in theme parks, and 208 were institutional.

Until 1997, these theaters were located in museums, science centers, and other educational institutions as well as a few zoos. In 1997, IMAX introduced a smaller, less expensive projection system that was the catalyst for commercial 35mm theaters owners and operators to integrate the theaters into multiplexes. Traditionally, the films were 30 to 50 minutes long, mostly documentaries. By 2000, the institutional theaters still comprised 70 percent of the market.

The first independent producers of these films were Greg MacGillivray and the late Jim Freeman. They began with surfing films in 1973. The cameras they used weighed 80 pounds, but they paid IMAX to make a camera with better specifications. Since that time, the MacGillivray Freeman company has led the independent way with 20 productions. The company’s film Everest, which was made for a reported $6 million and opened in 1998, grossed over $76 million by the end of its U.S. run in July of 2000.

Formats

In 2002, IMAX introduced a process to convert 35mm film to 15/70 (15 perforations/70mm process), their standard. Known as DMR, for digital remastering, the process started a new wave of converting longer feature films to be shown on the larger screens. Since the film frame for large format is 10 times the size of 35mm film, the films have better clarity and sound when projected on multistory screens. There were two DMR films in 2002 and 2003, three in 2004, and four in 2005, and six were expected in 2006. Although they either coincide with the 35mm version or are booked later, the DMR version of a film tends to remain in the theater longer. On the other hand, their average booking length is 77 days compared to films made specifically for the giant screen, which remain 211 days. These figures, from LF Examiner, are by year. An individual large-format film can appear on screens off and on for several years. T-Rex, which was originally released in October 1998, was still on a U.S. screen somewhere in June 2006. There is ongoing controversy about whether or not fiction features belong on a giant screen. However, that is for you to decide. Suffice it to say that the economies of scale are vastly different.

Finances

That brings us to the bottom line for these films. Since I have been covering the industry for The Film Entrepreneur, there has been little real data to obtain. As of December 2005, the LF Examiner discontinued boxoffice information. Editor/publisher James Hyder says on the publication’s website:

Readers are advised not to assume that the box office information on LF films provided here (or in other publications or Web sites) is complete or representative of the entire LF film market. In the conventional film industry, an independent agency collects and tabulates box office data directly from theaters for all films in release. Box office data for LF films are not reported the same way. Some LF distributors choose to provide data for their films to trade publications, but the practice is not universal, nor are the data independently audited or verified. In general, distributors that choose to report do so for the perceived marketing value. Therefore, films reporting their box office numbers are typically stronger than average. Films doing poorly generally cannot afford or prefer not to report. However, this does not mean that all films that do not report are poor performers. Some would undoubtedly place in the top half of these lists. But their distributors have chosen not to report because they believe weekly box office numbers are not a very useful measure of the LF industry’s performance. We agree.

That being said, Variety does print boxoffice dollars. There are filmmakers wanting to be a part of this industry, and it is the only reference they have to revenue. The problem comes on the cost side, not only the budgets but also how distributors of giant screen films calculate their fees. Even if the commercial theater owners work the same fee arrangement between themselves and the distributor, what is the deal with the institutions? In addition, in 10 years of covering this part of the film industry, I have never found a written analysis of the split between the distributor and the producer. Anecdotally, various distributors have told me that the split is the opposite of what we would assume for an independent film—65 percent to the distributor and 35 percent to the producer. This makes it a little difficult to write a business plan for equity investors.

After attending the annual conference of the Large Format Cinema Association (in 2006 it merged with the Giant Screen Theater Association to form the Giant Screen Cinema Association), I have found that independent producers generally are funding films as they would other documentaries—with grants, corporate donations, and funds from specific groups that may have a social or business interest in the subject of the film. The ongoing independent producers, MacGillivray Freeman, nWave, and others, have made profits from earlier films and, in some cases, distribute their own films. This lack of financial knowledge also makes it difficult to approach equity investors with a business plan. Information does change over time, however. As with other subjects, it’s important to do your own research.

As DVD has overtaken the VHS market, the number of direct-to-DVD movies (often called DVD premieres) has grown. At least half of my clients in 2005 and the first half of 2006 have wanted to add a section in their business plan about making direct-to-DVD movies. To consider mentioning this business segment as a future goal is one thing; trying to raise money from equity investors can be a problem. Here is what we know now.

While very little data exists about direct-to-DVD, it is clear that a majority of the product is from studios and/or franchises of films previously released and popular in the theatrical marketplace. These films have a ready-made audience. In its 2005 Fourth Quarter and Year End Home Video Rental Market Analysis, Rentrak, the point-of-sale tracking company, says that while U.S. consumer rental spending on a la carte and subscription rentals on the combined DVD/VHS formats declined 3.4 percent in 2005 from 2004, there was a strong revenue showing in the direct-to-video, television/cable, music, foreign, and documentary categories. Sound good so far? The bad news is that, although formerly a haven for very mini-budget horror and urban films, the direct-to business now is dominated by those franchises for popular feature films.

Direct-to-DVD animated films have been a lucrative business, as Disney has proven with its sequels to The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, and The Little Mermaid. DisneyToon has produced nine of the top 10 direct-to-DVD videos of all time. DreamWorks released Shrek 4-D as a Universal Studios theme park show and video premiere in 2003 and is planning a direct-to-DVD Shrek franchise similar to the straight-to-home video sequels from Disney, beginning with its first release in 2008 or 2009.

In Rentrak’s list of top-renting direct-to-video titles for 2005, four of the films are animated sequels (Mulan II, Tarzan II, Lilo & Stitch 2, Aloha Scooby-Doo) and another is a live action sequel, The Sandlot 2. Of the other five, Carlito’s Rise to Power, which was a hybrid being released into theatrical and video at the same time, is a prequel to Brian de Palma’s classic Carlito’s Way. The rest of the videos included two starring Wesley Snipes, one with Jean Claude Van Damme, and the other with Steven Seagal. All four were made by established production companies with their own funds and distributed by studio home video divisions. Not only do all these films have a built-in awareness, but the distributors still spend significant amounts of money to publicize the films.

Nevertheless, there have been anecdotal stories about success in going direct-to-Netflix, another DVD distributor. From the previous edition of this book, there is Rob Pollard’s story of putting his film on Netflix and getting an HBO distribution deal due to the number of rental units. There have been reports from other independent filmmakers that they have made their money back with a direct-to-DVD film. Using viral marketing through the Internet to niche groups, such as wrestling clubs, pilots associations, or subscription DVD clubs, can bring in revenue.

To the best of my knowledge, there is no real database available for direct-to, even for a fee. The Rentrak report that I have been quoting includes only those ten films. Therein lies the problem for including direct-to-DVD in a business plan. Although you can find people to quote on how profitable they can be, investors are likely to ask for projections. Occasionally, someone tells me that they have written a business plan for direct-to-video. When I ask what they used for data, the answer is, “You don’t want to know.” I advise readers not to go down that road. The best way to start a direct-to business is to use your own money, make a mini-budget film, and test the profit-making waters. Only then do you want to write a business plan to raise money from equity investors.

Small Screens

Short attention span theater, or “video snacks,” as Video Business refers to them, are proving very popular. The small screen took a big step forward in 2005 when Google announced that it would download to cell phones. A first impression of downloading to cell phones and downloading from the Internet was that theater screens might become an anachronism. Of course, that incorrect impression has been dealt with already. The potential for selling entertainment products certainly is entering a new frontier. In fact, the newest award in broadcasting excellence by The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Daytime Emmy Awards covers this format. For sports content initially, the award will be specifically for the tiny screens found on cell phones, iPods, PlayStation Portables (PSPs), and computer media player software. The Academy plans to expand the award to other categories, including news and documentary, business and financial reporting, and daytime television. The award will be reserved for original content such as “video blogs, web programs, event coverage, mobile phone serials and other video-on-demand content.” This step caused the New York Times to comment that the announcement gives new meaning to the line Gloria Swanson made famous in Sunset Boulevard: “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.”

The Yankee Group estimates that pure mobile entertainment— games, music, and video—accounted for about $500 million last year, less than 5 percent of the wireless carriers’ data revenue. And the data revenue represented a small fraction of voice revenue. Although people are watching video on their phones in increasing numbers, another researcher, eMarketer, predicts that even by 2009, fewer than 10 million subscribers will be willing to pay for premium services.

According to the research organization The NPD Group, mobile phone sales to consumers in the United States reached

34.8 million units in the first quarter of 2006. With the October 2005 launch of iTunes’ video service, NPD said that Movielink’s market share dropped from previous levels. CinemaNow stayed flat. An executive at NPD was quoted as saying that awareness of CinemaNow and Movielink was still lower than that of the better advertised iTunes. The point remains that there are an increasing number of ways to get digital video.

Google Video’s television downloads, priced at $1.99, kept getting compared to movies costing $19.95 to $25.99 at those two Internet downloading companies. As of May 2006, the Wall Street Journal reported that Apple and iTunes had sold 15 million video downloads since launching its TV show service. During a panel on mobile content at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival, representatives from cell phone providers and content providers agreed that this platform was good for games, short films, television programs, and perhaps even documentaries. However, it is unlikely that this will make a big impact on features in the near future.

The business model for all of this activity is unclear, with different equipment and content providers struggling for position. Not all companies will be able to download to all cell phones. If you are distributing a movie to theater screens, theoretically (and ignoring the clout that studios have with exhibitors), you can put the film on any screen, if you have the print money and a willing exhibitor. You aren’t blocked by the fact that the exhibitor may be making his own films. At the very least, you can take similar films and see how many screens they played on, what revenue they grossed, etc. With cell phones, however, at this point the picture is different. Certain cell phone providers have indicated that they want to have their own content. Some may make agreements with Google, Yahoo!, and other content providers; others may not. For example, HBO Mobile on Cingular Wireless, paying a monthly fee, gets five-minute versions of The Sopranos. In addition, there may continue to be limits on the amount of downloading an individual can do. Both Sprint and Cingular currently offer plans for unlimited data downloads at $80 per month, but other companies are limiting or planning to limit the amount of downloading.

Interestingly, at a Milken Institute Conference in 2006, the Vice President for Marketing at Cingular Wireless, referring to the understanding that they must create compelling new content, said, “But the fact is, no one knows that it is.” No one is pushing the small screen as a destination for feature films. Given the difficulty that consumers still have in downloading movies to a computer or television set, it seems unlikely this technology will be any easier on handheld screens in the near future.

TABLE 6.1

Crazed Consultant Films International Selected Comparative Documentary Films Revenues and Costs, 2002–2006 (in Millions of Dollars)

Note: Budgets are not available for many documentaries.

(a) Equals distributor’s share of U.S box office.

(b) Includes television, cable, video, and all other nontheatrical sources of revenue.

(c) Includes both theatrical and ancillary revenues.

(d) Equals domestic rentals, domestic other, and foreign.

(e) Gross profit before distributor’s fee is removed.