The Industry

The cinema is an invention without a future.

LOUIS LUMIERE

Moving images had existed before. Shadows created by holding various types of objects (puppets, hands, carved models) before a light were seen on screens all over the world. This type of entertainment, which most likely originated in Asia with puppets, was also popular in Europe and the United States. Then the Lumiere brothers created the cinematograph, an early form of moving camera, in Paris in the late 1800s. Little did they know.

Next came Thomas Alva Edison with his kinetograph, and shortly thereafter, the motion picture industry was born. Edison invented the first camera that would photograph moving images in the 1890s. Even Edison did not have a monopoly on moving pictures for long. Little theaters sprang up as soon as the technology appeared. In 1903, Edison exhibited the first narrative film, The Great Train Robbery. Seeing this film presumably inspired Carl Laemmle to open a nickelodeon, and thus the founder of Universal Studios became one of the first “independents” in the film business. Edison and the equipment manufacturers banded together to control the patents that existed for photographing, developing, and printing movies. Laemmle decided to ignore them and go into independent production. After several long trials, Laemmle won the first movie industry antitrust suit and formed Independent Moving Pictures Company of America. He was one of several trailblazers who formed start-up companies that would eventually become major studios. As is true in many industries, the radical upstarts who brought change eventually became the conservative guardians of the status quo.

Looking at history is essential for putting your own company in perspective. Each industry has its own periods of growth, stagnation, and change. As this cycling occurs, companies move in and out of the system. Not much has changed since the early 1900s. Major studios are still trying to call the shots for the film industry, and thousands of small producers and directors are constantly swimming against the tide.

Identifying Your Industry Segment

Industry analysis is important for two reasons. First, it tests your knowledge of how the system functions and operates. Second, it reassures potential partners and associates that you understand the environment within which the company must function. As noted above, no company works in a vacuum. Each is part of a broader collection of companies, large and small, that make the same or similar products, or deliver the same or similar services. The independent filmmaker (you) and the multinational conglomerate (most studios) operate in the same general ballpark.

Film production is somewhat different when looked at from the varied viewpoints of craftspeople, accountants, and producers. All of these people are part of the film industry, but they represent different aspects of it. Likewise, the sales specifications and methods for companies such as Panavision, which makes cameras, and Kodak, which makes film stock, are different not only from each other, but also from the act of production. Clearly, you are not going to make a movie without cameras, film, or video, but these companies represent manufacturing concerns. Their business operations function in a dissimilar manner, therefore, from filmmaking itself. When writing the Industry section of your business plan, narrow your discussion of motion pictures to the process of production and distribution of a film and focus on the continuum from box office to the ancillary (secondary) markets. Within this framework, you must also differentiate among various types of movies. Making the $300 million 35mm Lord of the Rings trilogy is not the same as producing the $1,100 digital video My Date with Drew. A film that requires extensive computer-generated special effects is different from one with a character-driven plot. Each has specific production, marketing, and distribution challenges, and they have to be handled in different ways. Once you characterize the industry as a whole, you should discuss the area that applies specifically to your product.

In your discussion of the motion picture industry, remember that nontheatrical distribution—that is, DVD, cable, pay-per-view, the Internet, and domestic and foreign television—are part of the secondary revenue system for films. Each one is an industry in itself. However, they affect your business plan in terms of their potential as a revenue source.

Suppose you plan to start a company that will supply films specifically for cable or the DVD market. Or you plan to mix these products with producing theatrical films. You will need to create separate industry descriptions for each type of film. Television has a different industry model from the video industry, which in turn differs from music. This book focuses on theatrically distributed films, but the business models for some of the other segments of the entertainment industry are discussed in Chapter 6.

A Little Knowledge Can Be Dangerous

You can only guess what misinformation and false assumptions about the film industry the readers of your business plan will have. Just the words film and marketing relate all sorts of images. Your prospective investors might be financial wizards who have made a ton of money in other businesses, but they will probably be uneducated in the finer workings of film production, distribution, and marketing. One of the biggest problems with new film investors, for example, is that they may expect you to have a contract signed by the star or a signed distribution agreement. They do not know that money may have to be in escrow to sign the star or that the distribution deal will probably be better once you are well into production. Therefore, it is necessary to take investors by the hand and explain the film business to them.

You must always assume that the investors have no previous knowledge of this industry. Things are changing and moving all the time, so you must take the time to be sure that everyone involved has the same facts. It is essential that your narrative show how the industry as a whole works, where you fit into that picture, and how the segment of independent film operates. Even entrepreneurs with film backgrounds may need some help. People within the film business may know how one segment works, but not another. As noted in Chapter 3, “The Films,” it can be tricky moving from working for a studio or large production company to being an independent filmmaker. The studio is a protected environment. The precise job of a studio producer is quite simple: make the film. Other specialists within the studio system concentrate on the marketing, distribution, and overall financial strategies. Therefore, a producer working with a studio movie does not necessarily have to be concerned with the business of the industry as a whole. Likewise, if you are a filmmaker in another country, your local industry may function somewhat differently. Foreign entertainment and movie executives may also be naive about the ins and outs of the American film industry.

The history of Universal Studios proves that executives in other countries may not understand our system. In 1990, Japanese conglomerate Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. bought MCA Inc., the parent company of Universal Pictures. After five years of turmoil and disappointing results, they sold MCA/Universal to Canada’s Seagram in 1994, which sold it to French communications/water company Vivendi in 2000. In 2003, Vivendi sold Universal Pictures to General Electric. Some foreign companies have hired consultants to do in-depth analyses of certain U.S. films in order to understand what box office and distribution mean in this country. As you go through this chapter, think about what your prospective investor wants to know. When you write the Industry section of your business plan, answer the following questions:

- How does the film industry work?

- What is the future of the industry?

- What role will my company play in the industry?

The rest of this chapter compares studio and independent motion picture production. It also provides some general facts about production and exhibition.

Motion Picture Production and the Studios

Originally, there were the “Big Six” studio dynasties: Warner Brothers (part of Time Warner, Inc.), Twentieth Century Fox (now owned by Rupert Murdoch), Paramount (now owned by Viacom and owner of DreamWorks SKG, which was purchased in December 2005), Universal (now NBC Universal), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (now a private company functioning mostly as a distributor and co-owned by a consortium composed of Sony Corporation of America, Providence Equity Partners, Texas Pacific Group, Comcast Corporation, and DLJ Merchant Banking Partners), and Columbia Pictures (now Sony Pictures Entertainment). After the Big Six came The Walt Disney Company. Together, these studios are referred to as “the Majors.” Although the individual power of each has changed over the years, these studios still set the standard for the larger films.

Until the introduction and development of television for mass consumption in the 1950s, these few studios were responsible for the largest segment of entertainment available to the public. The advent of another major medium changed the face of the industry and lessened the studios’ grip on the entertainment market. At the same time, a series of Supreme Court decisions forced the studios to disengage from open ownership of movie theaters. The appearance of video in the 1970s changed the balance once again. Digitally recorded movies, which will be the next big paradigm shift, are discussed at the end of this chapter.

How It Works

Today’s motion picture industry is a constantly changing and multifaceted business that consists of two principal activities: production and distribution. Production, described in this section, involves the developing, financing, and making of motion pictures. Any overview of this complex process necessarily involves simplification. The following is a brief explanation of how the industry works.

The classic “studio” picture would typically cost more than $10 million in 1993. Or, conversely, seldom could you independently finance above that figure, unless you were an international figure like Jake Eberts. Now the threshold for indies has moved to $20 million, as more high-budgeted independent films have come into the market, thanks in part to foreign money. Still, many high-budget films need the backup a studio can give them. Occasionally, the studio will take a chance on a lower budget (from their perspective, $10 million) that may not have a broad appeal. However, the studio can spread that risk over 15 to 20 films. Currently, they prefer the “tentpole” films whose budgets for a single film may top $200 million.

The typical independent investor, on the other hand, has to sink or swim with just one film. It is certainly true that independently financed films made by experienced producers with budgets of more than $10 million are being bankrolled by production companies with consortiums of foreign investors, but for one entity to take that kind of risk on a single film is not the rule. For a studio to recoup the investment on even a $10-million film requires at least a $25-million box office to cover both the budget and distribution costs.

At a studio, a film usually begins in one of two ways. The first method starts with a concept (story idea) from a studio executive, a known writer, or a producer who makes the well-known “30-second pitch.” The concept goes into development, and the producers hire scriptwriters. Many executives prefer to work this way. In the second method, a script or book is presented to the studio by an agent or an attorney for the producer and is put into development. The script is polished and the budget determined.

The nature of the deal made depends, of course, on the attachments that came with the concept or script. Note that the inception of development does not guarantee production, because the studio has many projects on the lot at one time. A project may be changed significantly or even canceled during development. The next step in the process is preproduction. If talent was not obtained during development, commitments are sought during preproduction. The process is usually more intensive because the project has probably been “greenlighted” (given funding to start production). The craftspeople (the “below-the-line” personnel) are hired, and contracts are finalized and signed. Despite periodic lawsuits due to handshake deals, producers do strive to have all their contracts in place before filming begins. The filming of a motion picture, called “principal photography,” takes from 12 to 26 weeks, although major cast members may not be used for the entire period. Once a film has reached this stage, the studio is unlikely to shut down the production. Even if the picture goes over budget, the studio will usually find a way to complete it.

After principal photography, postproduction begins. This period typically lasts 6 to 9 months, but can be shorter due to continuing technological developments.

Tracking the Studio Dollar

Revenues are derived from the exhibition of the film throughout the world in theaters and through various ancillary outlets. Studios have their own in-house marketing and distribution arms for the worldwide licensing of their products. Because all of the expenses of a film—development, preproduction, production, postproduction, and distribution—are controlled by one corporate body, the accounting is extremely complex.

Much has been written about the pros and cons of nurturing a film through the studio system. From the standpoint of a profit participant, studio accounting is often a curious process. One producer has likened the process of studio filmmaking to taking a cab to work, letting it go, and having it come back at night with the meter still running. On the other hand, the studios make a big investment. They provide the money to make the film, and they naturally seek to maximize their return.

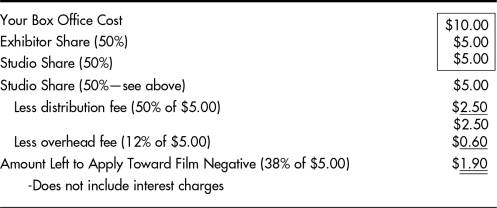

If your film is marketed and distributed by a studio, how much of each ticket sale can you expect to receive? Table 4.1 provides a general overview of what happens when a finished film is sent to an exhibitor. The table traces the $10.00 that a viewer pays to see a film. On average, half of that money stays with the theater owner, and half is returned to the distribution arm of the studio. It is possible for studios to get a better deal, but a 50 percent share is most common. The split is based on boxoffice revenue only; the exhibitor keeps all the revenue from popcorn, candy, and soft drinks.

For all intents and purposes, the distribution division of a studio is treated like a separate company in terms of its handling of your film. You are charged a distribution fee, generally 40 to 60 percent (we’re using a 50 percent average), for the division’s efforts in marketing the film. Because the studio controls the project, it decides the amount of this fee. In Table 4.1, the sample distribution fee shown is 50 percent of the studio’s share of the ticket sale, or $2.50, leaving 50 percent of the boxoffice revenues still in the revenue stream. Next comes the hardest number to estimate: the film’s share of the studio’s overhead. “Overhead” is all of the studio’s fixed costs—that is, the money the studio spends that is not directly chargeable to a particular film. The salaries for management, secretaries, commissary employees, maintenance staff, accountants, and all other employees who service the entire company are included in overhead. A percentage system (usually based on revenues) is used to determine a particular film’s share of overhead expenses.

TABLE 4.1

Tracking the Studio Dollar

Note: This example is based on average results. An individual film may differ in actual percentages.

It should be noted that the studios did not make up this system; it is standard business practice. At all companies, the nonrevenue-producing departments are “costed” against the revenue-producing departments, determining the profit line of individual divisions. A department’s revenue is taken as a percentage of the total company revenue. That percentage is used to determine how much of the total overhead cost the individual department needs to absorb.

In Table 4.1, a fixed percentage is used to determine the overhead fee. Note that it is a percentage of the total rentals that come back to the studio. Thus, the 12 percent fee is taken from the $5.00, rather than from the amount left after the distribution fee has been subtracted. In other words, when it is useful, the distribution division is a separate company to which you are paying money. Using that logic, you should be charged 12 percent of $3.00, but, alas, it doesn’t work that way.

Now you are down to a return of $2.40, or 48 percent of the original $5.00, to help pay off the negative cost. During the production, the studio treats the money spent on the negative cost as a loan and charges you bank rates for the money (prime rate plus one to three percentage points). That interest is added to the negative cost of your film, creating an additional amount above your negative cost to be paid before a positive net profit is reached.

We have yet to touch on the idea of stars and directors receiving gross points, which is a percentage of the studio’s gross dollar (e.g., the $5.00 studio share of the total boxoffice dollar in Table 4.1). Even if the points are paid on “first dollar,” the reference is only to studio share. If it has several gross point participants, it is not unusual for a boxoffice hit to show a net loss for the bottom line.

Studio Pros and Cons

When deciding whether to be independent or to make a film within the studio system, the filmmaker has serious options to weigh. The studio provides an arena for healthy budgets and offers plenty of staff to use as a resource during the entire process, from development through postproduction. Unless an extreme budget overrun occurs, the producer and director do not have to worry about running out of funds. In addition, the amount of product being produced at the studio gives the executives tremendous clout with agents and stars. The studio has a mass distribution system that is capable of putting a film on more than 3,000 screens for the opening weekend if the budget and theme warrant it. Batman Begins, for example, opened on 3,858 screens, and Mission Impossible III opened on 4,054 screens. Finally, the producer or director of a studio film need not know anything about business beyond the budget of the film. All the other business activities are conducted by experienced personnel at the studio.

On the other hand, the studio has total control over the filmmaking process. Should studio executives choose to exercise this option, they can fire and hire anyone they wish. Once the project enters the studio system, the studio may hire additional writers and the original screenwriters may not even see their names listed under that category on the screen. For example, the original co-writers of The Last Action Hero asked for an arbitration hearing with the Writers Guild because the studio did not give them screenwriting credit. The Writers Guild awarded them “story by” credit, but the screenwriting credit remained with the later writers. Generally, the studio gets final cut privileges as well. No matter who you are or how you are attached to a project, once the film gets to the studio, you can be negotiated to a lower position or off the project altogether. The studio is the investor, and it calls the shots. If you are a new producer, the probability is high that studio executives will want their own producer on the project. Those who want to understand more about the studio system should watch Christopher Guest’s film The Big Picture, Robert Altman’s The Player, The Last Shot, or the Aquaman segments in HBO’s series Entourage. I also suggest reading William Goldman’s books Adven-tures in the Screen Trade and sequel Which Lie Did I Tell?: More Adventures in the Screen Trade, Dawn Steel’s They Can Kill You but They Can’t Eat You, and Lynda Obst’s Hello, He Lied. The studios are filled with major and minor executives in place between the corporate office and film production. There are executive vice-presidents, senior vice-presidents, and plain old vice-presidents. Your picture can be greenlighted by one executive, then go into turnaround with her replacement. The process of getting decisions made is a hazardous journey, and the maxim “No one gets in trouble by saying no” proves to be true more often than not.

Motion Picture Production and the Independents

What do we actually mean by the term “independent”? Defining “independent film” depends on whether you want to include or exclude. Filmmakers often want to ascribe exclusionary creative definitions to the term. When you go into the market to raise money from investors (both domestic and foreign), however, being inclusive is much more useful. If you can tell potential investors that the North American box office for independent films in 2005 was $3.4 billion, they are more likely to want a piece of the action. The traditional definition of independent is a film that finds its production financing outside of the U.S. studios and that is free of studio creative control. The filmmaker obtains the negative cost from other sources. This is the definition of independent film used in this book, regardless of who the distributor is. Likewise, the Independent Film and Television Alliance (IFTA, formerly AFMA—the American Film Marketing Association) defines an independent film as one made or distributed by “those companies and individuals apart from the major studios that assume the majority of the financial risk for a production and control its exploitation in the majority of the world.” In the end, esoteric discussions don’t really matter. We all have our own agendas. If you want to find financing for your film, however, I suggest embracing the broadest definition of the term.

When four Best Picture Oscar nominations went to independent films in 1997, reporters suddenly decided that the distributor was the defining element of a film. Not so. A realignment of companies that began in 1993 has caused the structure of the industry to change at a faster pace than before. And a surge in relatively “mega” profits from low-budget films has encouraged the establishment of “independent” divisions at the studios. By acquiring or creating these divisions, the studios handle more films made by producers using financing from other sources. Disney, for example, purchased Miramax Films, maintaining it as an autonomous division. New Line Cinema (and its then specialty division, Fine Line Pictures) and Castle Rock (director Rob Reiner’s company) became part of Turner Broadcasting along with Turner Pictures, which in turn was absorbed by Warner Bros. Universal and Polygram (80 percent owned by Philips N.V.) formed Gramercy Pictures, which was so successful that Polygram Filmed Entertainment (PFE) bought back Universal’s share in 1995, only to be bought itself by Seagram-owned Universal. Eventually, Seagram sold October Films (one of the original indies), Gramercy Pictures, and remaining PFE assets to Barry Diller’s new USA Networks, and those three names disappeared into history. Sony Pictures acquired Orion Classics, the only profitable segment of the original Orion Pictures, to form Sony Classics. Twentieth Century Fox formed Fox Searchlight. Metromedia, which owned Orion, bought The Samuel Goldwyn Company, and eventually was bought itself by MGM. Not to be left out of the specialty film biz, Paramount launched Paramount Classics in 1998 (reorganized as part of Paramount Vantage in 2006), and in 2003 Warner Bros. formed a specialty film division, Warner Independent Pictures.

In 2003, Good Machine, a longtime producer and distributor of independent films, became part of Universal as Focus Features. The partners split between going to Universal and staying independent as Good Machine International. Focus operated autonomously from Universal and was given a budget for production and development of movies by its parent company. Universal, in turn, used Focus as a source of revenue and to find new talent. By the definition used in this book, then, the films produced by Focus are independent as are the films that they acquire. What is the payoff for all this recombining? Four Best Picture Oscar nominations went to independent films in 2003, 2004, and 2005, continuing the industry’s demonstration of love for these pictures.

Then there is DreamWorks SKG. Formed in 1994 by Steven Spielberg, David Geffen, and Jeffrey Katzenberg, the company was variously called a studio, an independent, and—my personal favorite—an independent studio. In the last quarter of 2005, Paramount bought the DreamWorks live-action titles and their 60-title library plus worldwide rights to distribute the films from DreamWorks Animation (spun off as a separate company in 2004) for between $1.5 and $1.6 billion. Paramount then sold the library to third-party equity investors, retaining a minority interest and the right to buy it back at a future date. Since Spielberg can greenlight a film budget up to $90 million, Business Strategies will continue to count films solely financed by DreamWorks as independent.

In-house specialty divisions provide their parent companies with many advantages. As part of an integrated company, specialty divisions have been able to give the studios the skill to acquire and distribute a different kind of film, while the studio is able to provide greater ancillary opportunities for the appropriate low-to-moderate budget films through their built-in distribution networks. Specialty labels can prove themselves assets in more literal ways as well. At one point, Time Warner planned to sell New Line for $1 billion (Turner paid $600 million for the company in 1993) to reduce the parent company’s debt load. New Line’s founder, Robert Shaye, and the other principals had always made their own production decisions, even as part of Turner Pictures. In the summer of 1997, New Line secured a nonrecourse (i.e., parent company is not held responsible) $400 million loan through a consortium of foreign banks to provide self-sufficient production financing for New Line Cinema. Making their own films means that New Line keeps much more of their revenue than they would if they were a division of Warner Bros. (Everyone liked this situation until the release of The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring, the first film of the trilogy, earned $1.1 billion worldwide, and all three films went on to earn $3.5 billion.)

If films remain independently funded, the prime definition of being an “independent” has been met, no matter which distributor’s logo is tacked onto it. It is up to you, the reader, to track what has happened in the meantime.

How It Works

An independent film goes through the same production process as a studio film from development to postproduction. In this case, however, development and preproduction may involve only one or two people, and the entrepreneur, whether producer or director, maintains control over the final product. For the purposes of this discussion, we will assume that the entrepreneur at the helm of an independent film is the producer.

The independent producer is the manager of a small business enterprise. She must have business acumen for dealing with the investors, the money, and all the contracts involved during and after filming. The producer is totally responsible from inception to sale of the film; she must have enough savvy and charisma to win the confidence of the director, talent, agents, attorneys, distributors, and anyone else involved in the film’s business dealings. There are a myriad of details the producer must concentrate on every day. Funding sources require regular financial reports, and production problems crop up on a daily basis, even with the best-laid plans. Traditionally, the fortunes of independent filmmakers have cycled up and down from year to year. For the past few years, they have been consistently up. In the late 1980s, with the success of such films as Dirty Dancing (made for under $5 million, it earned more than $100 million worldwide) and Look Who’s Talking (made for less than $10 million, it earned more than $200 million), the studios tried to distribute small films. With minimum releasing budgets of $5 million, however, they didn’t have the experience or patience to let a small film find its market. Studios eventually lost interest in producing small films, and individual filmmakers and small independent companies took back their territory.

In the early 1990s, The Crying Game and Four Weddings and a Funeral began a new era for the independent filmmaker and distributor. Many companies started with the success of a single film and its sequels. Carolco built its reputation with the Rambo films, and New Line achieved prominence and clout with the Nightmare on Elm Street series. Other companies have been built on the partnership of a single director and a producer (or group of production executives) who consistently create high-quality, money-making films. For example, Harvey and Bob Weinstein negotiated a divorce from The Walt Disney Company in 2005 and created The Weinstein Company, raising $490 million equity in only a few months.

Then there are the smaller independent producers, from the individual making a first film to small- or medium-sized companies that produce multiple films each year. The smaller production companies usually raise money for one film at a time, although they may have many projects in different phases of development. Many independent companies are owned or controlled by the creative person, such as a writer-director or writer-producer, in combination with a financial partner or group. These independents make low-budget pictures, usually in the $25,000 to $5 million range. Open Water and Tarnation—made for $120,000 and $60,000, respectively—are at the lower end of the range, often called “no-budget.” When a film rises above the clouds, a small company is suddenly catapulted to star status. In 1999, The Blair Witch Project made Artisan Entertainment a force to contend with, and in 2002, My Big Fat Greek Wedding was a hit for IFC Films (now owned by Rainbow Media) and gave Gold Circle Films higher status as a domestic independent producer and distributor.

Tracking the Independent Dollar

Before trying to look at the independent film industry as a separate segment, it is helpful to have a general view of how the money flows. This information is probably the single most important factor that you will need to describe to potential investors. Wherever you insert this information in your plan, make sure that investors understand the basic flow of dollars from the revenue sources to the producer.

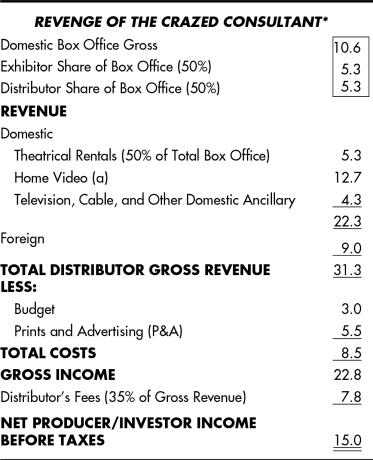

Table 4.2 is a simplified example of where the money comes from and where it goes. The figures given are for a fictional film and do not reflect the results of any specific film. In this discussion, the distributor is at the top of the “producer food chain,” as all revenues come back to the distribution company first. The distributor’s expenses (“P&A,” or prints and ads) and fees (percentage of all revenue plus miscellaneous fees) come before the “total revenue to producer/investor” line, which is the “net profit.”

The boxoffice receipts for independent films are divided into exhibitor and distributor shares, just as they are for studio films (see Table 4.1). Here, the average split between distributor and exhibitor is 50/50. This is an average figure for the total, although on a weekly basis the split may differ. Generally, independent companies do not have the same clout as the studios, and the exhibitor retains a greater portion of the receipts. In the example in Table 4.2, of the $10.6 million in total U.S. box office, the distributor receives $5.3 million in rentals. This $5.3 million from the U.S. theatrical rentals represents only a portion of the total revenues flowing back to the distributor. Other revenues are added to this sum as they flow in (generally over a period of two years), including domestic ancillaries (home video, television, etc.) and foreign (theatrical and ancillary).

TABLE 4.2

Tracking the Independent Dollar (in millions of dollars)

* This is a fictional film. (a) In 2005, DVDs accounted for 91% of total home video.

The film production costs and distribution fees are paid out as the money flows in. From the first revenues, the prints and ads (known as the “first money out”) are paid off. In this example, it is assumed that the P&A cost is covered by the distributor. Then, generally, the negative cost of the film is paid back to the investor. Often the investor will live with a 90/10 or 80/20 split with the producer until the initial investment is paid off. After the distributor has taken his fees (35 percent or less), the producer and the investor divide the remaining money.

Pros and Cons

Independent filmmaking offers many advantages. The filmmaker has total control of the script and filming. Depending on agreements with distributors, it is usually the director’s film to make and edit. Some filmmakers want to both direct and produce their movies; this is like working two 36-hour shifts within one 24-hour period. It is better to have a director direct and a producer produce, as this provides a system of checks and balances during production that approximates many of the pluses of the studio system. Nevertheless, the filmmaker is able to make these decisions for herself. And if she wants to distribute as well, preserving her cut and using her marketing plan, that is another option—not necessarily a good one, as distribution is a specialty in itself, but still an option.

The disadvantages in independent filmmaking are the corollary opposites of the studio advantages. Because there is no cast of characters to fall back on for advice, the producer must have experience or must find someone who does. Either you will be the producer and run your production, or you will have to hire a producer. Before you hire anyone, you should understand how movies are made and how the financing works. Whether risking $50,000 or $5 million, an investor wants to feel that your company is capable of safeguarding his money. Someone must have the knowledge and the authority to make a final decision. Even if the money comes out of the producer’s or the director’s own pocket, it is advisable to have the required technical and business knowledge before starting.

Money is hard to find. Budgets must be calculated as precisely as possible in the beginning, because independent investors may not have the same deep pockets as the studios. Even if you find your own Bob Yari (Yari Film Group Productions) or Jeff Skoll (Participant Productions) with significant dollars to invest, that person expects you to know the cost of the film. The breakdown of the script determines the budget. When you present a budget to an investor, you promise that this is a reasonable estimate of what it will cost to make what is on the page, and that you will stay within that budget. The investor agrees only on the specified amount of money. The producer has an obligation to the investor to make sure that the movie does not run over the budget.

Production and Exhibition Facts and Figures

The North American box office reached $9 billion in revenues in 2005, according to the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). Worldwide sales for independent films in 2005 were more than $7 billion. Included in this number is a North American box office for indies of $3.4 billion (as calculated by Business Strategies) and more than $1 billion in U.S. ancillary revenues. Aggregate international sales (i.e., countries outside of the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico) for independent films are calculated by IFTA through a statistical survey of its members. While U.S. theatrical distribution is still the first choice for any feature-length film, international markets are gaining even greater strength than they had before.

Separating the gross dollars into studio and independent shares is another matter. While databases often include films distributed by specialty divisions of the studios as studio films, being acquired does not change the independent status of the film. In order to estimate the total for independent films, you have to add those from all the independent distributors plus films that have been acquired by the majors. As there is no database for “independent films acquired by studios,” a precise figure is not possible.

Theatrical Exhibition

At the end of 2005, there were 38,594 theater screens (including drive-in screens) in the United States. This represents an increase of 6.2 percent over the number in 2004 and 3.9 percent over the previous high of 37,396 screens in 2000. Since 1990, however, there has been an overall increase in the number of screens of 64 percent. A downward trend from 2001 through 2004 is attributed to the closing of run-down, out-of-date theaters that were competing with larger, state-of-the-art structures. Despite many ups and downs, such as the advent of television and the growth of the home video market (currently 91 percent DVD), theatrical distribution has continued to prosper.

Film revenues from all other sources are driven by theatrical distribution. For pictures that skip the theatrical circuit and go directly into foreign markets, video, television, or another medium, revenues are not likely to be as high as those for films with a history of U.S. boxoffice revenues and promotion. The U.S. theatrical release of a film usually ends within six months. While studio films begin with a “wide” opening on thousands of screens, independent films start slower and build. The rentals will decline toward the end of an independent film’s run, but they may very well increase during the first few months. It is not unusual for a smaller film to gain theaters as it becomes more popular.

Despite some common opinions from distributors, the exhibitor’s basic desire is to see people sitting in the theater seats. There has been a lot of discussion about the strong-arm tactics that the major studios supposedly use to keep screens reserved for their use. (This is sometimes referred to as “block booking.”) Exhibitors, however, have always maintained that they will show any film that they think their customers will pay to see. Depending on the location of the individual theater or the chain, local pressures or activities may play a part in the distributor’s decision. Not all pictures are appropriate for all theaters. Recent events have shown that independent films with good “buzz” (prerelease notices by reviewers, festival acclaim, and good public relations) and favorable word-of-mouth from audiences will not only survive but also flourish. What the Bleep Do We Know? and My Big Fat Greek Wedding are good examples. Both films started in a small number of theaters and cities. As audiences liked the films and told their friends about them, the movies were given wider release in chain theaters in more cities. Of course, good publicity gimmicks help. People still ask me if 1999’s The Blair Witch Project is a real story; I have even been accused of lying when I say that it is utterly fictional, a “mockumentary” no more real than This Is Spinal Tap or Bob Roberts!

Table 4.3 shows actual motion picture distributor revenue streams in 2004 and estimates for those revenues in 2014 forecasted by Kagan Research, LLC, as reported in the October 13, 2005, issue of Motion Picture Investor (see www.kagan.com). Total worldwide revenue was up $3.9 billion over 2003. According to the report, 2005 is showing a slowdown in home video but is still expected to show a growth of 7 percent over 2004.

Overall, the next few years are looking good. Total distribution revenue is expected to grow 56.5 percent by 2014. Kagan points out that in 2002, total domestic revenues were at $21.0 billion compared to $17.9 billion in international revenues. The gap had closed in 2004, with domestic revenues at $23.6 billion and international at $23.0 billion. Although home video has slowed in growth, its losses will be taken over the television revenue streams. As the chart shows, through the next decade television revenues are the only segment to gain market share.

TABLE 4.3

Actual (2004) and Estimated (2014) Distributor Revenue Stream (in Millions of Dollars)

ACTUAL 2004 | ESTIMATED 2014 | |

Revenue Source | ||

Domestic | ||

Theatrical Rentals | 4,845 | 6,701 |

Home Video | 12,410 | 15,961 |

Broadcast Networks | 557 | 375 |

Syndicated Television | 141 | 227 |

Pay Television | 1,678 | 3,227 |

Basic Cable | 2,264 | 4,316 |

Merchandising/Licensing | 1,110 | 1,602 |

PPV/DBS/VOD | 555 | 2,266 |

Hotel/Airlines/Other | 80 | 131 |

Foreign | ||

Theatrical Rentals | 4,974 | 8,459 |

Home Video | 10,706 | 17,666 |

Network Television, Syndication | 2,878 | 4,637 |

Pay Television | 2,459 | 4,128 |

Merchandising/Licensing | 1,819 | 2,389 |

PPV/Hotel/Airlines | 160 | 906 |

TOTAL DISTRIBUTOR REVENUE | 46,636 | 72,991 |

Source: Copyright (c) Kagan Rsearch, LLC. Used with permission.

Kagan estimates that by 2014, television revenue will account for 27.5 percent of the market. The company predicts that the rollout of VOD technologies will make accessing content in the home easier than it is today and create a shift in consumer patterns. This shift also depends on a major push by VOD/PPV providers to close the windows between home video and VOD/PPV, a medium in which a movie normally comes out 45 days after it has debuted on home video. This plan depends on cooperation by the film distributors.

As you may be reading this book several years hence, be aware that the film industry is shifting at a greater rate than it ever did in the last decade. Many different and competing analyses and projections appear in the news media. A 500-channel television universe seems less certain than it did in the 1990s. Despite fears that the audience will leave the theaters and stay at home, most experts believe that theatrical exhibition will always be the vehicle that drives the popularity of products played in homes and in other outlets. People have always enjoyed an evening out and are expected to continue to do so. Even though you can watch a movie on your personal computer or send that signal to your home television, theatrical exhibition is not likely to disappear during our lifetime and continues to flourish.

Digital Film

The film industry has been on the brink of a major technological revolution with digital filmmaking and screens. The revolution is still waiting to take off, as it was in all previous editions of this book, but now it appears to be idling on the runway. There were 324 digital screens in the United States at the end of 2005, up from just 85 in 2004, according to Screen Digest. Worldwide, there were 849, up from 335 in 2004. The National Association of Theater Owners (NATO) predicts 1,200–1,500 digital screens by the end of 2008. Exhibitors, studios, and large independents have announced agreements for the installation of from 2,500 to 20,000 digital systems between 2007 and 2010; however, studios, exhibitors, and distributors are still debating how to finance them. At the moment, a final print in 35mm is still the way to go; this will probably be the case well into 2008.

On June 5, 2000, Twentieth Century Fox became the first company to transmit a movie over the Internet from a Hollywood studio to a theater across the country. Well, to be more exact, it originated in Burbank, California, and went over a secure Internetbased network to an audience at the Supercomm trade show in Atlanta. (Trivia buffs, take note: the film was the animated space opera Titan A.E.) As we roll rapidly through the sixth year of the twenty-first century, filmmakers keep calling me about the $30,000 digital film they are going to make. But ask yourself a question: When will digital film be a business? My short answer is: When Regal Cinemas converts its more than 6,000 theater screens to digital projection. The company currently owns close to 20 percent of all the screens in the United States. Until its largest shareholder, Philip Anshutz, retired from the Board of Directors in March 2006, the company’s long-term business strategy was to own 30 percent of the screens; however, a recent announcement said that no more screen purchases are contemplated.

How much progress has been made since those conventiongoers saw Titan A.E.? Some movies have been digitally projected into select theaters. George Lucas put a digital Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace in five theaters. Disney’s Dinosaur was also shown digitally. However, while at this point it is important, digital film is not yet a business. A report by SRI Consulting in 1998 stated that movies encoded as digital data files “either recorded on optical disc and physically shipped or broadcast via satellite will increasingly replace film prints as the preferred method for distributing movies to theaters by 2005.” Of course, we know how shaky such predictions can be. Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith debuted on 3,661 screens in 2005, earning a total of $380.6 million domestically. Anyone can do the math. That gross would not exist if the film had been released in digital format only.

There is not a definite count of digital screens in the world; however, by speaking to manufacturers, consultants have estimated that in the United States and Canada there are 80 d-cinema screens in 67 sites, with an additional 79 screens located in 75 sites internationally. The conversion costs are considerable. The cost for each digital projector is $150,000, along with the more than $20,000 per screen required for the computer that stores and feeds the movies.

Until the digital market is larger, include money in your budget to upgrade your digital film to 35mm. Don’t assume that the distributor wants to do it. Look at it from his viewpoint. If the distributor is planning on releasing 10 to 20 films a year, at $55,000 or more per film for a quality upgrade, he is likely to opt for a film that is already in 35mm format. “But,” you say, “my film will be so overwhelming, he will offer to put up the money.” It is within the realm of possibility, but I wouldn’t want the distribution of my film to rest on that contingency. Or you may say, “I’ll wait until the distributor wants the film, and then I’ll raise the money for the upgrade.” Although this is within the realm of possibility, don’t just assume you will be able to raise the money. Those pesky investors again. Whether it is one investor or several in an Offering, you have to go back to those people for the additional $50,000. Will they go for it? Maybe yes, maybe no. If they don’t, then you may be stuck. If you raise the money from additional sources, you still have to get the agreement of the original investors. After all, you are changing the amount of money they will receive from your blockbuster film.

Then there is the question of quality. When technology experts from the studios are on festival or market panels, they always point out that audiences don’t care how you make the film; they care how it looks. If you can really make your ultra-low-budget digital film have the look of a $5 million or $10 million film, go for it. But be honest with yourself.

What Do You Tell Investors?

All business plans should include a general explanation of the industry and how it works. No matter what your budget, investors need to know how both the studio and the independent sectors work. Your business plan should also assure investors that this is a healthy industry. You will find conflicting opinions; it is your choice what information to use. Whatever you tell the investor, be able to back it up with facts. As long as your rationale makes sense, your investor will feel secure that you know what you are talking about. That doesn’t mean he will write the check, but at least he will trust you.

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but 20 pictures are not necessarily worth 20,000 words. The introduction of user-friendly computer software has brought a new look to business plans. Unfortunately, many people have gone picture-crazy. They include tables and graphs where words might be better. Graphs made up about three-fourths of one company’s business plan that I saw. The graphs were very well done and to a certain extent did tell a story. The proposal, put together by an experienced consultant, was gorgeous and impressive—for what it was. But what was it? Imagine watching a silent film without the subtitles. You know what action is taking place, and you even have some vague idea of the story, but you don’t know exactly who the characters are, what the plot is, or whether the ending is a happy one. Similarly, including a lot of graphs for the sake of making your proposal “look nice” has a point of diminishing returns.

There are certainly benefits to using tables and graphs, but there are no absolute rules about their use. Some of the rules for writing screenplays, however, do apply:

- Does this advance the plot?

- Is it gratuitous?

- Will the audience be able to follow it?

Ask yourself what relation your tables and graphs have to what investors need to know. For example, you could include a graph that shows the history of admissions per capita in the United States since 1950, but this might raise a red flag. Readers might suspect that you are trying to hide a lack of relevant research. You would only be fooling yourself. Investors looking for useful information will notice that it isn’t there. You will raise another red flag if you include multiple tables and graphs that are not accompanied by explanations. Graphic representations are not supposed to be self-explanatory; they are used to make the explanation more easily understood. There are two possible results: (1) the reader will be confused, or (2) the reader will think that you are confused. You might well be asked to explain your data. Won’t that be exciting?