Six

Alice Beckenbach

Alice Curtiss Beckenbach came from a mathematical family. She was born in 1917, two years after the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) was founded, and over the next eighty-five years she was a regular attendee at winter and summer national MAA meetings. Alice’s mother Sigrid Eckman was president of her class at Radcliffe, a class that included Helen Keller. There she met Alice’s father David Raymond Curtiss, who completed his PhD in mathematics at Harvard in 1903. Curtiss spent his academic career at Northwestern University, many of those years as department chairman. He was author of the second Carus Monograph (on complex analysis) and was president of the MAA from 1935 to 1936. David Curtiss’s brother Ralph was an eminent astronomer at the University of Michigan.

Alice’s brother John Curtiss, who had a PhD in mathematics from Harvard, headed the Applied Mathematics Division of the National Bureau of Standards from 1946 to 1953 when the Division was charged with developing mathematical methods for exploiting the first generation of electronic computers. He was the founding president of the Association for Computing Machinery and later served as executive director of the American Mathematical Society.

Alice was a dual mathematics-chemistry major at Northwestern and about to start graduate study in mathematics when she met her first husband, Albert W. Tucker, who was teaching summer school at Northwestern. Tucker was a well-known topologist at Princeton who later turned to mathematical programming and game theory, famous for Kuhn-Tucker theorem and the prisoner’s dilemma. Tucker was chair of the Princeton mathematics department in the 1950s and 1960s. He instigated the now-famous common room teas at Princeton. His PhD students and postdocs included two Nobel laureates in economics, John Nash and Robert Aumann, along with Marvin Minsky, the founder of the AI Laboratory at MIT. Al Tucker was president of the MAA from 1961 to 1963 and was one of the early recipients of the MAA Distinguished Service Award.

Alice’s two sons, Alan and Tom, are mathematicians and have served the MAA in many roles; both have been MAA first vice-presidents. Her third child, Dr. Barbara Cervone, is a prominent educator who currently heads the nonprofit group What Kids Can Do. Alice has two grandchildren with PhDs in the mathematical sciences: Thomas J. Tucker, a number theorist at the University of Rochester, and Lisa Tucker Kellogg, a computational biologist at the National University of Singapore.

In 1960 Alice married Ed Beckenbach, who spent most of his career at UCLA, where he was chair of the mathematics department and a founder of the Pacific Journal of Mathematics. He also was a co-author of the Dolciani K–12 series of “new math” textbooks, widely used in the 1960s and 1970s. Ed was the chair of the MAA Publications Committee for over a decade. Posthumously, he was also a recipient of the MAA Distinguished Service Award.

Alice is now 92 and no longer able to attend MAA meetings, but her heart and soul will be with mathematicians whenever they gather. [She died on March 18, 2010.]

Alan C. Tucker

Thomas W. Tucker

September 2009

Reminiscences of a Mathematologist

A mathematologist may be defined as someone who specializes in the study of mathematicians and their peculiarities.

It is no secret that the mathematics professor is a breed of human both admired and shunned by the ordinary person (“and perdaughter,” to quote Ralph Boas) and locked lifelong in a love-hate relationship with the remainder of the human race. The “victim” body count in my own family thus far includes my father, brother, two husbands, two sons, and now at least three grandchildren on their way to joining the list. Perhaps I should add that although treatment for my family disease of mathematics is mainly supportive, there is no known cure for this puzzling abnormality other than the radical surgery of amputating the entire head. Needless to add, medical and legal experts frown on this crude type of instant therapy.

Figure 6.1 Alice with sons (L to R) Tom and Alan and Andy Gleason.

Accordingly the voice of experience may be permitted to share some reminiscences from a lifetime of close acquaintance with the world of mathematicians. Many of their personality profiles will be punctuated with examples of verse from the unpublished works of several of their colleagues, who would doubtless prefer to remain anonymous.

To the average layman, an obvious peculiarity of the serious mathematician is a frequently glassy-eyed expression along with a tendency to absentmindedness owing to intense preoccupation with inner thought. Probably the most famous example of the absent-minded mathematician was that lovable old sandal-clad hippie Albert Einstein, who could never remember such finishing sartorial touches as combing his hair or donning a pair of socks. When he took up residence at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, the university students used to sing a quatrain in his honor with these words:

Here’s to Einstein, Albert E.,

Father of Relativity.

You’ll know him by his fiddler’s locks

And by his utter lack of socks.

Thus it was that one snowy morning some years ago when my then nine-year-old son, Tom Tucker, the mathematician-to-be, was leaving for school, I was proud to observe the glassy-eyed look on his face as he waved goodbye and headed out into the wintry blast. The fact that he had on socks as he trudged through the snow, although no shoes, made me doubly proud that our budding Einstein at least had some common sense. So, you see, I too at least had symptoms of the family disease.

Another example of such absent-mindedness is the story about one of the greatest mathematicians of this century, David Hilbert, who was a professor at Göttingen University, the leading shrine of mathematics in the world in the first quarter of the century, until Hitler drove out the most brilliant minds there. In those days, a new member of the faculty there was supposed to introduce himself to his colleagues in a very formal manner: he put on a black coat and a top hat and took a taxi to make the rounds of the faculty houses. If the Herr Professor was at home, the new colleague was supposed to go in and chat for a few minutes. Once such a new colleague came to Hilbert’s house and Hilbert decided (or perhaps his wife did it for him) that he was at home. So the new professor came in, sat down, put his top hat on the floor, and started talking. . . . All very well, but he didn’t know how to stop talking, and Hilbert became more and more impatient, eager to get back to an important theorem he was inventing that day. Finally, Hilbert stood up, picked up the top hat from the floor, put it on his own head, touched the arm of his wife and said, “I think, my dear, we have delayed the Herr Professor long enough”—and walked out of his own house.

Figure 6.2 Einstein with Adolf Hurwitz and daughter Lisi Hurwitz.

Figure 6.3 Who needs shoes? Tom Tucker at age nine.

Figure 6.4 Hilbert—not always patient.

Joseph Wedderburn, so they say,

Has Einstein beat in every way.

He sublimates the urge of sex

By playing with the powers of x.

Obviously, Professor Wedderburn would not have qualified to be included in the World Almanac table on labor statistics under the heading: “Number of People in the U.S. Gainfully Employed by Sex.”

My father, D. R. Curtiss, was a very active member of both the MAA and American Mathematical Society in the first half of the [twentieth] century. In the mid-1930s, when he was president of the MAA and I was studying mathematics in college, I often accompanied him to the winter and summer joint mathematics meetings. There my main contribution was in the practice, not the theory, of games, offering a variety of amusing diversions to some of the more playful attendees. I fondly recall, for example, regular ping-pong challenges with Warren Weaver at AAAS meetings, tennis with Nathan Jacobson, Garrett Birkhoff, Hassler Whitney, and Marston Morse (among other buffs of the game), and also an occasional piano duet with the latter, and bridge games with various others.

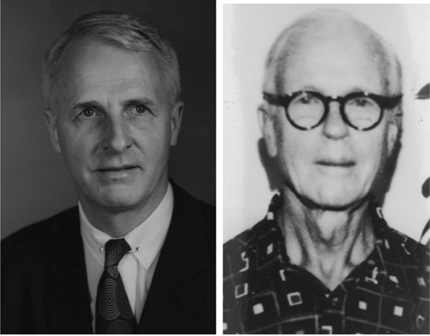

Figure 6.5 D. R. Curtiss, father of Alice Beckenbach.

Figure 6.6 Ping pong buffs—Garrett Birkhoff (left) and Hassler Whitney (right).

At the 1935 winter meeting in St. Louis, Professor Lars Ahlfors, first winner of the Fields medal, had just arrived from his native Finland to join the faculty at Harvard. He requested and I gave him his first driving lessons on a narrow, icy road along the Mississippi River. So clearly, this “math groupie” had courage, too, along with her more playful talents.

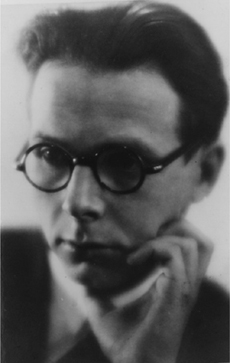

Figure 6.7 Lars Ahlfors.

Another of my recollections of the meetings in those days was the fearsome triumvirate of Lefschetz, Tamarkin, and Wiener sitting in the front row at the ten-minute talks given by young new PhDs who were locked in a desperate scramble for teaching jobs during the Great Depression. Lefschetz would be as usual alert and on the edge of his seat, Wiener blissfully snoring, and Tamarkin poised somewhere in between, all three waiting to pounce on the hapless victim with such ego-busting remarks as, “After I obtained that result back in—think it was 1926—I found some interesting extensions that I’d like to mention. . . .”

In 1938 my career as a mathematologist soared to heady new heights when I left my childhood town of Evanston, Illinois, with its then isolationist, ultraconservative, church-on-every-corner, national-headquarters-of-the-Woman’s-Christian-Temperance-Union mystique, to become the bride of A. W. Tucker, a mathematics professor at Princeton University. The town of Princeton was small but cosmopolitan and something of a Grand Central Station for mathematical refugees from Nazi Europe. My husband’s office was sandwiched between Einstein’s on one side and that of the noted physicist Niels Bohr on the other. Among the resident notables whom one often spotted strolling up Nassau Street at the time were the writer Thomas Mann, the pianist Robert Casadesus, and, a few years later, Bertrand Russell.

Figure 6.8 Wiener, one of the Gang of Three, who could constitute a tough audience.

The Institute for Advanced Study was well established then and shared quarters with the Princeton mathematics department in Fine Hall—and a fine hall it was, with a couch and fireplace in every office, plus a men’s room with full bath. The department chairman was Luther P. Eisenhart, who was honored with the following quatrain:

Figure 6.9 Luther P. Eisenhart served as Department Head, Dean of Faculty, and Dean of the Graduate School at Princeton.

Here’s to Eisenhart, Luther Pfahler,

In four dimensions he’s a whaler.

He built a country club for Math

Where you can even take a bath.

The tenured mathematics faculty consisted of Eisenhart, S. Bochner, H. Bohnenblust, C. Chevalley, A. Church, S. Lefschetz, H. P. Robertson, A. W. Tucker, J.H.M. Wedderburn, E. Wigner, and S. S. Wilks. Instructors or postdoctoral fellows were N. Steenrod, Ralph Fox, J. Tukey, Brockway McMillan, and C. B. Tompkins, among others.

At tea time the Fine Hall common room was a gathering place for the mathematicians and mathematical physicists (probably and most notable among the latter being Richard Feynman, then a graduate student), and a center for spirited games of kriegspiel and arguments about Bourbaki. It was also apparently the living quarters of Paul Erdős; at least, I remember opening a drawer in one of the cupboards there and coming upon his underwear and pajamas casually stashed away. Alas, the life of a proper mathematics department chairman is not an easy one, and it particularly rankled the dignified Professor Eisenhart to see Erdős gleefully sliding down the banisters in Fine Hall whenever he had just “sunk up a new serum [thought up a new theorem].”

Figure 6.10 Did Paul Erdős live in the Fine Hall Common Room?

Figure 6.11 Lefschetz—The Great White Father.

Figure 6.12 Albert W. Tucker

Lefschetz, too, kept the air crackling around Fine Hall, needling his adversaries and amusing his friends with his quick wit and outspoken opinions. The Great White Father, as he was fondly known to his graduate students, was memorialized in verse as follows:

Irrepressible as hell,

When laid at last beneath the sod,

He’ll then begin to heckle God.

My then husband, Albert Tucker, was a protégé of Lefschetz and the appointed peace-maker between the math department and the university administration when Lefschetz succeeded Eisenhart as Chairman. The engineering department, in particular, detested the math department, which in turn had naught but contempt for the engineers. Bitter indeed were their battles over the teaching of calculus. Now, Tucker was a careful, responsible sort of person, and a notable exception to the prototype victim of mathematicitis. He was not absent-minded, and he could count beautifully. In the following quatrain describing his trials and tribulations, the name Pétard refers to a group of six young Princeton Turks who submitted to the Monthly an anonymous article that was a clever spoof on Bourbaki. But the Monthly editor was loath to accept anonymous articles, and something of a brouhaha ensued. The article was then submitted under the name H. Pétard. So, on with the verse:

Figure 6.13 Hermann Weyl in a not too saintly pose.

Tucker likes to keep things straight,

Topologize, and not be late.

But in these things his life’s made hard

By Alice, Lefschetz, and Pétard.

Permanent mathematical members of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the late 1930s were, in addition to Einstein: J. W. Alexander, Kurt Gödel, Marston Morse, John von Neumann, Hermann Weyl (whose poetic contribution concludes with:

Figure 6.14 “Uncle” Oswald Veblen gave rather formal dinner parties.

For he is that most saintly German,

The One, the Great, the Holy Hermann.)

and not least of all, the magnetic mathematician-promoter and stately but genial anglophile, Oswald Veblen. Married to the sister of a famous British physicist, he, too, was immortalized in doggerel to this effect:

Hail to Uncle Oswald V.,

Lover of England and her tea.

He’s the only mathematician of note

Who needs four buttons to fasten his coat.

“Jimmy” Alexander was in many respects the Renaissance man of this notable group. He was a charming and ruggedly handsome millionaire, a skilled mountain climber, figure skater, ham radio expert, music lover, limerick collector, and a liberal who even marched in the Communist May Day Parade in New York.

Figure 6.15 James W. Alexander giving a ride to a delighted Lefschetz.

Social entertaining at that time was usually joint between the mathematics departments of the University and the Institute. A dinner party at the Veblens was a highly formal affair, with enough silver at each place setting to summon the Lone Ranger’s horse. After dinner there was demitasse for the ladies in one drawing room, while the gentlemen amused themselves over brandy and cigars in another.

Entertainment at the von Neumanns’, by contrast, was far more informal. For example, the wives were included when the men gathered for some lively after-dinner raconteur competition. The von Neumanns’ preference for casual entertaining hit something of a peak at one of their wartime parties when they recruited Army Specialized Training Program servicemen wandering by on the street to join in the carousing inside. Vivid in memory, too, was a light-hearted party there in honor of the von Neumanns’ daughter Marina, now a distinguished economist, on the occasion of her fourteenth birthday when she had just come to live with him and her stepmother, Klara. A book recently published, entitled The Prisoner’s Dilemma by William Poundstone, gives sort of a biography of John von Neumann, as well as of game theory.

Another von Neumann incident that I recall with some amusement occurred at a dinner at the home of Professor Emil Artin and his wife Natasha. The guests were seated at card tables. At my table there were just three of us: two mathematical greats, von Neumann and Weyl, and one mathematologist. Norbert Wiener’s pioneering book Cybernetics had just been published, and von Neumann had been asked to review it for a leading journal. Weyl asked von Neumann for his opinion of the work, so the latter commented in true Hungarian style on its applications and implications, or rather on a lack of any, according to him. “But you know,” he added, “Wiener has zees inferiority complex, so when I wrote zees review . . . well, to tell zee truth, I just couldn’t!” It was von Neumann who claimed to have invented the popular definition of a Hungarian, namely: “It takes a Hungarian to go into a revolving door behind you and come out first.”

Artin was another eminent mathematical refugee from Germany. His son Michael was President of the American Mathematical Society (1991–1992) and a well-known mathematician at MIT.

Figure 6.16 John von Neumann gave somewhat informal dinner parties.

Stories about Johnny von Neumann are legion, but unfortunately no one seems able to recall any that were put to verse. One of his own favorite verses was this:

Figure 6.17 Marston Morse—a confident man.

There was a young man who cried “Run!”

The end of the world has begun!

The one I fear most

Is that damned Holy Ghost

I can handle the Father and Son.

Certainly he was an amusing raconteur and a notoriously wild driver, with gaping holes in his neighbor’s hedge to prove it. Perhaps that sheds some light on this line from a description of Princeton once given by the noted Institute physicist Freeman Dyson: “. . . where every prospect pleases, and only man is vile.” Nevertheless, it was generally agreed that von Neumann was the leading mathematical mind in the world at that time.

Then there was Marston Morse and his charming wife Louise, who were prime hosts to both resident and visiting mathematicians. Dinner at their home was always a delightful and delicious experience. The dynamic, multitalented, aquiline-nosed Morse, author of the definitive text, Calculus of Variations in the Large, was not known for a lack of self-confidence. For example, once at a dinner party he was seated next to the wife of a Princeton faculty member. She was a matter-of-fact, no-nonsense sort of person. A bit of polite exchange revealed the fact that they had grown up in the same town in Maine and that both had relatives with the same name. This prompted Professor Morse to comment with a touch of courteous enthusiasm, “You know, we might very well be cousins!”

“Oh, that’s ridiculous,” she replied firmly. “I doubt very much that we’re cousins.”

Shortly after, as the guests adjourned to the living room, Morse took his wife aside and whispered, “Say, what does that woman want in a cousin?”

Thus it is that the rather wicked quatrain in his honor ends with the lines:

His opinion of himself, we charge,

Like nose and book, are in the large.

But enough of this careening down memory lane. It’s still not too late to heed the sage advice that my father once gave me: “It’s simply not true that you have to say everything that comes into your head.”

![]()