3

Learner and Facilitator

What’s Inside This Chapter

What’s Inside This Chapter

• How learning preferences and styles affect faciliation decisions

• The multiple roles that facilitators fulfill

• Competencies required of a facilitator

• How to assess and select facilitators

The most important skill one can gain is the ability to learn. People need to understand their learning styles to maximize their learning effectiveness. Facilitators need an understanding of learning styles so they can incorporate them into the classroom experience.

Learning Preferences: How People Take in Information

Adults retain about 10 percent of what they read, 20 percent of what they hear, 30 percent of what they see, and 50 percent of what they hear and see. But, if adults become actively involved in their learning, those percentages rise to 70 percent of what they see and 90 percent of what they see and do (Mitchell 1998).

In chapter 2 you were introduced to the three main learning preferences: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic/tactile. Although different learning preferences are always accommodated in a good course design, the facilitator can achieve higher levels of participant involvement and learning by also tailoring facilitation methods to the learning preferences of the specific group of participants.

Noted

Noted

More than half of the population is primarily visual learners, about 30 percent are primarily auditory learners, and kinesthetic learners represent less than 10 percent of the population (Chan 2010).

Visual Learning Preference

Visual learners take in and process information through what they see. They learn best from printed information, pictures, graphics, and media, especially videos. Other visual learners prefer to learn through reading and writing, as in structured note taking. Incorporating some of the following in your delivery accommodates the visual learner’s preferences:

• flipcharts

• virtual whiteboards with annotation tools

• demonstrations

• diagrams, charts, and drawings

• powerpoint

• participant materials such as manuals, reference material, prework assignments, and workbooks

• interactive computer simulations

• YouTube videos to present or reinforce content or for demonstrations.

In the virtual classroom, facilitators can incorporate almost all of these methods. They can use an in-class whiteboard instead of a flipchart to chart participant responses and make diagrams, charts, and drawings in real time. They can highlight key ideas, words, and phrases when speaking and can share videos (from YouTube or other sources), PowerPoint slides, articles, and other visual material. They can also use a webcam and microphone for demonstrations, which provides a visual and auditory experience.

Think About This

Think About This

The use of a webcam may reduce interactivity; just as in a brick-and-mortar environment, some participants are shy to speak up. So, anonymity helps with the interaction.

Most virtual classrooms have the capability to create polls, which allows the group to express ideas and give feedback. The primary use of polling is for surveys of learner responses to questions in a variety of formats (multiple-choice or open-ended text answers). Polling engages learners while reinforcing content. For example, a case study could be presented and then learners could be polled to see what the next step would be to solve the case. Facilitators of online training programs can post PowerPoints, videos, and articles, as well as predeveloped charts, diagrams, and drawings for the learners to access.

In both online training and the virtual classroom, participant material can easily be downloaded at a work location or home, which increases engagement because participants can fill in missing information as it is presented. In addition, it is easy to send prework to each participant, and have it be completed and turned in online. Because all the materials are electronic, these steps require less time, and there is a reduction of costs to produce, copy, and ship the material.

Threaded discussions, discussion boards, and chats encourage online interaction between learners. The facilitator posts a question, issue, or job application in the discussion forum, and then participants can respond to that posting, as well as those of other participants. Chats allow learners to communicate with one another in real time. These chats can be public (for all learners to read and respond to) or private (much like a dyad in a classroom session). Chat can be used for providing feedback, asking questions, or making comments.

Think About This

Think About This

When asking learners questions in a virtual classroom, they can respond verbally or through chat. This allows for multiple responses.

Auditory Learning Preference

Auditory learners take in and process information that is heard, including words, alliteration, and songs. They have a keen ability to remember what they have heard. To aid the learner with an auditory preference, you can incorporate:

• presentations and lectures

• facilitative discussions

• demonstrations

• group projects and activities with feedback

• verbal instructions

• audiovisuals

• songs and background instrumental music

• panel discussions

• question-and-answer sessions

• rhymes, chants, and poetry.

These methods are all available in the virtual classroom. Because the training is synchronous, participants can interact with one another and the facilitator. The facilitator can also invite outside guests for presentations, question-and-answer sessions, and panel discussions. These guests simply join the class and can become shared moderators or presenters.

The virtual classroom also allows for developing teams and team assignments. When the projects are completed, the team can submit it to the facilitator and give a presentation. Team projects benefit from the use of a virtual team room or breakout room, which team members can access 24/7. This is synchronous—learners can share ideas and documents, and use a whiteboard to collaborate on their project. As facilitator, you will be able to join various team rooms to monitor progress and coach if needed. If the training program runs for a few days, you can also provide breakout rooms on a 24/7 basis for learners to use outside class time.

The team discussion forum is useful for individual teamwork discussions. The forum is secured, so that only team members can see and message their own team members.

Facilitators can make the audiovisual format of their presentation available for online learners to download. This allows them to see the media as they hear the presentation of content. The facilitator can also incorporate podcasts, senior management messages, videos, and other content into an audiovisual format.

As with the visual learner, the threaded discussions and discussion boards also encourage participant interaction.

Kinesthetic/Tactile Learning Preference

The kinesthetic learner and tactile learner are very similar in their preferences. The tactile learner is more touch oriented. Kinesthetic/tactile, or physical, learners take in and process information through physical experiences. They like direct involvement and learning. The kinesthetic/tactile learning preference directly relates to hands-on training and skill building. Here are some things you can do:

• hands-on practice

• role plays

• behavior modeling

• structured note taking (learners fill in blanks on handouts)

• simulations

• individual and group activities and projects

• have learners develop their own materials, such as drawings, flipcharts, and posters

• interactive computer simulations.

These learners’ needs are the more difficult to address, especially in the virtual classroom. Facilitators can have learners make their own drawings, engage in polling, or write their ideas on a virtual wallboard or PowerPoint slide by simply sharing presenter rights. Sharing participant materials can encourage structured note taking as the learner listens to the material.

For online learning with specific instructions, use individual and team projects requiring manipulation of information and on-the-job application. Pre- or post-online discussions can enhance the experience. More sophisticated software can provide 3-D graphics, which replicate a demonstration.

Because these learners are easily distracted, the virtual classroom experience should include varied experience, such as a mix of video, PowerPoint, facilitative discussion, Q&A, polling, and whiteboard recording.

Noted

Noted

The next time you see a learner who is doodling on her materials, think twice before assuming that this learner is bored. Kinesthetic/tactile learners doodle during lectures and other activities that provide little or no physical experience. They help themselves physically interact with the content by doodling and thereby keep themselves engaged in the learning.

Learning Preferences and the Facilitator

The more adults see, hear, say, and do, the greater the learning and retention. Therefore, facilitators need to use a variety of instructional strategies and media to address learner preferences. For example, although you still need to do some presenting, facilitated discussion allows others to voice their views and experiences (auditory learning preference). This approach also provides variety in presentation of content. Instructional strategies, such as simulations, group activities, demonstrations, practice, and role plays, provide learners with the opportunity to not only experience the content in a variety of ways, but also to meet the learning preferences of the participants. For the kinesthetic/tactile learner, it is important that lessons learned from these activities are reinforced and applied to on-the-job situations. When you use multiple forms of media, you meet the needs of the visual learner. When learners work and discuss the material together, you are providing an auditory experience. Your challenge is to simultaneously incorporate as many of these options as possible in your learning program.

Table 3-1 presents ways to align learning activities to online or virtual classroom learning environments. Table 3-2 provides a way for you to select learning activities according to their learning preferences.

Table 3–1. Aligning Learning Activities and Media With Online Training and Virtual Classroom Environments

Reprinted with permission from Performance Advantage Group (2015).

Basic Rule 4

Basic Rule 4

Use multiple forms of media and learning strategies to support learners’ taking in of content.

Table 3–2. Aligning Learning Activities and Media With Learning Preferences

|

Kinesthetic/Tactile |

Auditory |

Visual |

|

Supervised practice on the job |

Lectures |

Diagrams |

|

Simulations |

Discussions |

Charts and graphs |

|

Paper-and-pencil tests |

Demonstrations |

Graphics |

|

Physical analogies |

Brainstorming |

Color |

|

Note taking |

Question-and-answer sessions |

Training manuals |

|

Flowcharting |

Songs and lyrics |

Reading |

|

Case histories |

Music |

Handouts |

|

Group projects |

Coaching |

Flowcharts |

|

Role playing |

Rhymes |

Flipcharts |

|

Physical demonstrations |

Acronyms |

Wallboards and posters |

|

Hands-on activities |

Metaphors |

Whiteboards |

|

Building things |

Definitions |

Reference materials |

|

Puzzles |

Small group work |

Lists of parts or definitions |

|

Charades |

Panel discussions |

Films and videos |

|

Writing on flipcharts or wallboards |

Group or individual presentations |

Slides |

|

Whiteboards |

Group projects |

Maps |

|

Tools |

Films |

Observations |

|

Props |

Audiovisuals |

Demonstrations |

|

Toys |

“War stories” |

Posters and art |

|

Job aids |

Interactive computer simulations |

Slides and photos |

|

interactive computer simulations |

PowerPoint presentations | |

|

Interactive computer simulations |

Learning Styles: How Adults Process Information

Now that you have an understanding of how learners take in information (learner preferences), you can move on to how learners process that information. The different ways that people process information are called learning styles, of which there are five: achievers, evaluators, networkers, socializers, and observers.

Achievers

Achievers focus on accomplishing results and generally have the expertise to do so. People with this learning style are good at finding practical uses for ideas and theories. They enjoy being involved in new and challenging experiences and carrying out plans to meet those challenges. Achievers have the ability to solve problems, make decisions, and develop action plans based on implementing solutions to questions or problems. They want to find practical uses for the ideas and training content. Achievers like to accept the lead role in addressing those challenges.

Achievers like sequence, logical order, and clear, step-by-step directions. They are not strong in people orientation and have a tendency to take control with little regard for others’ feelings.

Because achievers are “take charge” people, you may need to rotate small group leadership roles to give other learners a chance to lead. Achievers want the facilitator to be practical and present what will really work back on the job. Facilitate the application-to-the-job material, ensuring completion of the activity. This is partly a design issue for online learning, but the facilitator can monitor progress and debrief activities to fit the on-the-job application. Have learners post and present their work so that they can learn from one another and provide feedback. You may consider beginning the session by reviewing a performance contract, if one was used (see chapter 5), to start achievers thinking about the application of the course content. Revisit the performance contract often.

Think About This

Think About This

To accommodate the learning style of achievers, you, as facilitator, can incorporate case studies, role plays, and action learning, and then debrief learners, emphasizing the real-world situations. Allow adequate time for the development of action plans for on-the-job application of the new knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs). Facilitative discussions and presentations should emphasize the link to the job in real-world terms. For example, you can ask, “How would you do this differently next time?”

In small group work, achievers may monopolize the conversation, dictate the direction and solution, and show little respect or patience for others’ opinions or experience. They want the activity’s directions to be stated logically with specific outcomes identified. You may need to revisit course ground rules concerning everyone’s participation, the values of others’ opinions, and mutual respect.

Evaluators

Sometimes referred to as thinkers, evaluators like to analyze a situation and use a logical process to resolve issues. They collect a great deal of information by asking many detailed questions, so the online facilitator needs to be readily available. They are also very concerned about working within the existing guidelines. Evaluators are good at assimilating a wide range of information and putting it into a concise, logical form, such as lists, charts, or planning tools. These learners are more interested in the basis of theory and the application of theory, and less on building relationships. The theory you present needs to be logically sound, exact, and supported by facts.

Evaluators need to see value and job-relatedness in learning activities and, for that matter, course content. They will want to set up an orderly way (logical steps) to address the purpose of the activity. Be aware, though, that the evaluator may challenge the expertise of the achiever and others.

Think About This

Think About This

To accommodate the learning style of evaluators, be sure to provide a summary of the theoretical basis of the content. Your debriefing of activities could build on the results and then discuss application to the job. Depending on the training design, you can also facilitate case studies, individual projects, and reading or research. In a group activity, the evaluator will want to know, in detail, the instructions, outcome, format of the presentation, sources of information, and ways to access that information.

Networkers

Networkers like to develop close relationships with others and avoid interpersonal conflict. For online and virtual classroom learners, the chat, coffee shop, and team discussion forums allow for interaction and building relationships. Because they are good listeners, networkers develop strong people networks. They are more compliant than others and are often easily swayed. Networkers also try to avoid risks, seek consensus, and are slower than others to make decisions. In group activities, networkers rarely disagree with others’ opinions; they are supportive and seek collaboration. Networkers take time to build trust and get personally acquainted with others. Although they are outgoing, they need direct feedback as a way of support.

Think About This

Think About This

You can use networkers to stimulate group interaction and involvement. Ask them what they think of others’ ideas. Provide direct feedback to their comments and contributions to group projects. Allow networkers to take the lead in ice-breaking activities. Provide opportunities for interaction in small groups and one-on-one activities. They respond well to peer teaching and tutoring.

Socializers

Socializers like to talk and share. They enjoy the spotlight and having fun. Although they like to get multiple perspectives, socializers are good at selling their ideas to others and building alliances. Not concerned with details or facts, they like to keep a fast pace and make quick, spontaneous decisions. Socializers are also good at brainstorming activities. In group work, the socializer wants to work quickly, seek others’ input, persuade others, provide some humor, and volunteer to make the presentation.

Socializers like presenting group activities, and must be reminded that a presentation requires depth; superficial responses are not enough. To accomplish this, ask socializers to give their rationale for the facts behind their comments. Strive to take them deeper into the content. In large group discussions, recognize their contributions but ask for alternative views. Socializers in the online or virtual classroom can benefit from using chat, threaded discussions, discussion boards, the coffee shop, and team discussion forums.

Think About This

Think About This

When you are a facilitator, you can use the socializer’s outgoing nature to stimulate group interaction. Socializers may be frustrated if the program goes too slowly for them. You may need to indicate that not all learners are as fast as they are when it comes to learning new ideas and skills. When providing instruction for learning activities, remind them that the process of arriving at decisions is as important as the decisions themselves.

Observers

Observers are best at viewing concrete situations from many different points of view. They prefer to observe and conceptualize rather than take action. They are reflective thinkers who enjoy situations that call for generating not just many ideas, but also a wide range of ideas. These learners are more interested in abstract ideas and concepts and less in building relationships. Observers want to take time to reflect and conceptualize, and don’t like to wing it.

You’ll want to create an experience, involve observers in that experience, and then let them reflect on it. Debriefing of activities could build on the results and go into more abstract ideas, such as generating future situations. Depending on the training design, you can also facilitate case studies and follow up with “what-if” scenarios to allow for changing conditions.

Think About This

Think About This

You’ll find when you facilitate group learning that demonstrations, case studies, and brainstorming are good ways to meet the needs of observers, especially if they have had the opportunity for individual work first. These activities can be followed up with “what-if” scenarios. You can also ask open-ended questions and record the responses. You’ll want learners to present their process for solving a case and the lessons learned, which link back to the course content. As a facilitator, you will want to provide time for participants to reflect on what they have experienced and make some notes about the meaning of those experiences and their application to the participants’ job or situation.

Identifying Learning Styles

As a facilitator, you will want to recognize and address the five different learning styles. A quick way to tentatively identify these styles is by observing the learners’ choices of words and behaviors. Table 3-3 provides a brief summary of verbal cues and learner behaviors to help you recognize these styles.

Table 3–3. Recognizing Learning Styles

|

Role |

Verbal Cue |

Learner Behavior |

|

Achiever |

• Tells, does little asking • Blunt, to the point • Asks for clear directions • Asks for clear, concise answers • Asks for application to the job |

• Does lots of talking • Takes charge, likes to be leader • Follows the participant guide, in order • Demonstrates little patience for nontask-related activities |

|

Evaluator |

• Asks for data, facts, sources • Focuses comments on the topic • Little personal sharing • Wants the details |

• Task oriented • Follows directions • Challenges others’ expertise • Develops steps to accomplish activities |

|

Networker |

• Asks many questions • Does little telling • Vocalizes support for others’ opinions • Seeks attention and feedback |

• Engages in effective listening • Seeks collaboration and consensus • Reserves personal opinions • Avoids conflict • Develops close relationships • Builds trust |

|

Socializer |

• Shares experiences • Tells stories • Digresses and gets off topic • Readily expresses personal opinion • Talks a lot • Uses language of persuasion |

• Makes quick, spontaneous decisions without all the information • Gets multiple perspectives • Has fun • Loves group activities and discussions |

|

Observer |

• Likes to conceptualize, “what if” discussions • Asks questions or makes off-topic comments • Makes “what about this” statements • Makes future application to discussions |

• Provides several alternatives to a problem or situation • Easily gets off topic • Wants fuller discussion on the idea • Not concerned with the concrete application of the ideas |

Now that you know about learner preferences for taking in content and learner styles for processing content, you, as a facilitator, will want to use both sets of information in making a conscious decision to meet the needs of your learners. Table 3-4 integrates learning preferences and styles with learning activity choices.

Table 3–4. Aligning Activities With Learning Preferences and Styles

Adapted from Deb Tobey LLC (2015).

Roles of a Facilitator

Facilitators wear many hats during the course of a learning event, and all these hats are critical to supporting an effective learning experience. An apt analogy might be the director of a play or movie: The director orchestrates everything that happens, from what the actors say and do, down to minute details of set design. These elements interact to support the goal of telling a story.

By the same token, all the roles facilitators fill and all the things facilitators do interact to support one goal: learning. While wearing these many hats, facilitators are also in charge of both the task (learning and applying knowledge and skills) and the process (how the learning and applying happen) of learning experiences. Each role described in the sections that follow focuses on managing a task or process.

Basic Rule 5

Basic Rule 5

Facilitate both the task and process of learning experiences.

Leader of the Group

Everything you say and do focuses on helping participants learn. As the leader, you create and sustain the environment so that classroom interactions (face-to-face or virtual) motivate participants to acquire new knowledge and skills. Your role is to help participants learn and apply the new knowledge and skills to their jobs.

In this role, the facilitator is in charge of leading both the task and the process aspects of learning. This process role is appropriate for the virtual classroom and online training if the facilitator develops a team approach to the online learners. This can be accomplished by raising hands, using emoticons, and incorporating such techniques as polling, threaded discussions, discussion boards, and chat.

Facilitators encourage group cohesiveness and direction throughout the participation process. They must manage the group involvement process, ensuring group members are treated as equals, encouraging group discussion, suggesting decision-making and problem-solving alternatives, guiding toward resolution, and promoting development of actions and follow-up plans. As leader, the facilitator must help team members to be sensitive to other members, involve all members, and establish and maintain group norms to help them function more effectively.

In the virtual classroom, barriers can be minimized by having participants engage in noncourse-related discussion in the coffee shop and team discussion forums, reading others’ profiles to gain an appreciation of the group’s background, and setting ground rules. The system can be set up to notify facilitators if individuals appear distracted. They can then call on the participants and get them more actively involved.

One thing leaders do in leading the task component is provide feedback on participants’ comments and individual and group activities. Individual comments and group discussions are ideal times to assess whether the learners are really getting the material. Your response gives them additional content and, at the same time, feedback on their understanding of the subject under discussion. Practice activities are great opportunities to provide balanced feedback. These same task-oriented actions are appropriate for the virtual classroom—online training requires the submission and response of ideas and content from the participant. Timely and complete feedback is critical for the online learner. There can also be an ongoing give-and-take between the participant and facilitator, which can take place through email, chat, or responses to threaded discussions.

Basic Rule 6

Basic Rule 6

As leader, you help participants learn and apply the new knowledge and skills to their jobs.

Manager of the Agenda

Having developed a schedule, it is your job to maintain that agenda; this is a task-focused facilitator role. Starting on time, whether in the morning or after breaks, can be difficult to enforce. Even when starting on time is a ground rule, it is still difficult to manage. Yet, starting on time and staying on time are important for completing all the content and fully experiencing the learning strategies.

Once you get behind, you have to make up time without sacrificing the quality of the learning experience. The learners will notice if you take longer than scheduled for an activity. Some will worry that the learning is compromised, and others will be so busy making sure you take a break at the right time that they will miss the learning!

You must also manage the time for facilitative discussion and various learning activities. It is very easy to respond to a question and then go down the garden path of various topics. Related? Yes. Important to meeting the objectives of the course? Well, maybe.

Think About This

Think About This

Should you share your course schedule with the learners? Except for telling them when breaks, meals, and the end of the day are, the answer is most often no. If you are facilitating properly, you will be constantly adjusting to the needs of the learners within the timeframes that you have set. If you share actual agenda item times, the learners will be more interested in whether you are keeping to the schedule than actually learning.

For the virtual classroom, starting on time is critical, especially since participants may be in other time zones. The facilitator also needs to check to make sure all microphones are working—that all participants can hear and respond—before beginning the session. In many cases, there is also a small lag time as participants respond to questions. So, build a little extra time into the schedule to accommodate these unavoidable delays.

Online training is not open ended—there is a schedule set up for deliverables. For longer online training, there is a master table outlining when specific deliverables are due. It is up to the participant to manage his schedule so that the work is submitted on time. This, in turn, allows the facilitator to provide feedback as planned.

Learning activities pose another opportunity to challenge your skills. You begin the activity according to schedule, providing clear instructions to the groups. However, as the time draws near, they need just a few more minutes. Then their presentations take longer than expected and the debriefing session draws questions. You are now off schedule.

However, even with these possibilities for getting off schedule, you are still expected to finish on time—this is a ground rule. Although you may be able to negotiate some extra time at the end of the day or have a working lunch, there is still the expectation of stopping on time. After all, you’re the leader and you manage the agenda.

Basic Rule 7

Basic Rule 7

Manage and maintain your agenda.

Role Model for Positive Behaviors

You must always—without exception—maintain a positive and professional demeanor; this is a critical part of your focus on process and is equally true for the virtual classroom. While it can be tough, seek positive solutions to constructive conflict; try to see the other’s point of view. Your modeling of professional behavior is critical to having a successful program. Professional behavior must also be exhibited in the facilitator–online participant relationship. All communications should maintain a professional demeanor.

Beyond this, model the behavior that you are teaching. For example, if you are teaching coaching skills, model the behavior of an exemplary coach. When explaining concepts, providing feedback, or making application to the job, model those coaching behaviors you are teaching. By so doing, participants can learn by observing and become more convinced that these skills really work.

Basic Rule 8

Basic Rule 8

Always maintain a positive and professional demeanor and model the behavior you are teaching.

Content Expert

Being an expert in your content is part of your task. To some extent, facilitators have credibility by virtue of standing before the group or engaging learners in an online or virtual environment, and you will not want to lose that credibility. The participants expect you to be a content expert, someone who’s able to speak beyond the script of the leader’s guide and make the content relevant to them.

How do you do this? One way is to ask and answer questions. You ask questions that take people deeper into the content than they currently are. By then taking their answers and going further or making application, you demonstrate your grasp of the content. You can have the same impact by answering questions completely, when appropriate. The familiar technique of handing it back to the group (“What do you think about that?”) can only work for so long. At some point, participants want to know what you think and why. This is an opportunity for you to enhance your stance as a content expert.

While the virtual classroom affords the same opportunity, threaded discussions, discussion boards, and chat features can provide additional opportunities to pose questions, review responses from multiple participants, and craft an in-depth response. In the online environment, the facilitator can pose questions and engage in a conversation using chat or similar methods.

Besides asking and answering questions, you can also share your experiences—not all experiences, but those relevant to the course content and application of that content to the job. This is also a viable option for both online training and the virtual classroom. As a content expert, you can blend your knowledge and job-related experience to enrich the learning experience. Your stories can make the content come alive, capture the interest of the group, and enhance your credibility as a content expert and facilitator. These things do not just happen. As you prepare to facilitate, plan for your questions and ways of sharing your experiences. If you just ad lib, you’re likely to stray from the learning objectives and lose your learners along the way.

Jargon is also important for the content expert. You must know and speak the language of your participants regardless of the learning environment. There is nothing more embarrassing than a participant asking a question and you don’t have a clue as to what she is saying. Your command of the language of the subject will go a long way to establishing and maintaining your credibility.

Basic Rule 9

Basic Rule 9

Demonstrate mastery of the subject, in both content and application to the job regardless of the learning environment.

Consultant

In your role as a consultant, an adviser, or a coach, you are tasked with helping the participants complete a critical task: to make sense of the concepts and apply them to their jobs within the context of their environment. This is the task part of learning, which goes beyond having learners complete action plans or a performance contract. You must help them see the implications of new knowledge and skills for their performance, that of their team, and that of their business unit (process of learning). After all, the ultimate purpose of your course is to close an identified performance gap that is important to the individual and the organization. This role is critical regardless of the learning environment. Although easier in the face-to-face or virtual classroom, the online learner also should have access to the facilitator to ensure that the training transfers to his performance on the job.

Your consultant role may take you beyond the classroom. In some cases (within reason), you may need to do some one-on-one consulting during lunch, a break, or even during the evening. When working with participants at a distance this can also be accomplished through video chat, emails, and various groupware programs. You may even have the opportunity to do some follow-up work to see the extent that the new knowledge and skills have transferred to the job. In your role as a consultant, you can go beyond the classroom and into the work environment. You can then identify enablers and barriers to knowledge and skill transfer, and help management address the situation. Ultimately, you are a business problem solver.

Basic Rule 10

Basic Rule 10

Consult with learners to clarify content and help them apply that content to their jobs, within their environment.

Facilitator Competencies

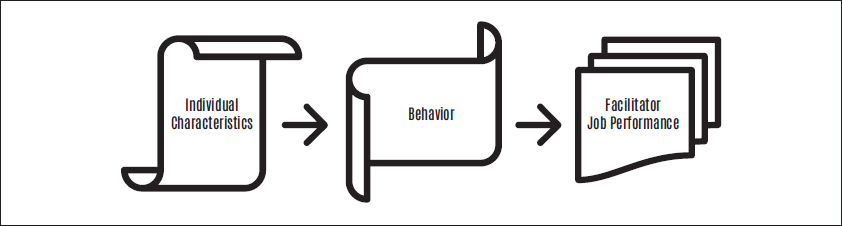

When most people talk about competencies, they usually think of knowledge and skills. In a broader sense, however, competencies also include individual characteristics (for example, supportiveness, achievement orientation, and initiative), which are manifested as behaviors. Facilitator characteristics drive facilitator behaviors, which then drive the facilitator’s job performance—the facilitation of learning. Figure 3-1 illustrates this domino effect.

Figure 3–1. Individual Characteristics Drive Performance

With this as a background, let’s look at some competencies that facilitators should possess. For ease of understanding, the competencies are grouped by major categories and accompanied by behavioral descriptions that align with that category.

Facilitators have several knowledge competencies:

• the organization (for example, its strategies, objectives, markets, customers, competitors, and products and services)

• adult learning principles

• learning theory and how it is applied to learning

• training evaluation

• needs assessment for a specific seminar or workshop

• organizational, job, and individual performance indicators

• instructional design and development

• diversity awareness as it relates to the implications of participant differences on learning

• methods and tactics to get organizational buy-in and support for learning

• group dynamics

• tactics for coaching and feedback

• technology and software for facilitating in an online and virtual classroom.

Learning facilitators also need to have the following skill competencies:

• operating equipment:

![]() computers and LCD projectors

computers and LCD projectors

![]() participant voting systems

participant voting systems

![]() operating the computer and various software packages

operating the computer and various software packages

![]() using the capabilities the platform has to offer

using the capabilities the platform has to offer

• confidently moving around the virtual classroom and engaging the online learner

• writing on flipcharts: preparing standard charts and recording participants’ comments

• writing on whiteboards and using annotation for the virtual classroom

• communicating verbally (including voice control and inflection) to present information

• communicating nonverbally with body positioning, gestures, and facial expressions

• summarizing and paraphrasing participant input

• providing coaching and feedback

• listening actively and effectively

• planning and debriefing learning activities

• thinking in terms of systems to see interrelationships among participants’ input by recognizing the connecting patterns.

Individual characteristics are best described as behavioral competencies. People demonstrate individual characteristics by how they behave in given situations. Table 3-5 is an extensive listing of these behavioral competencies, including a brief descriptor of each competency. There are 14 characteristic categories, each containing multiple behaviors.

For those not possessing a desired competency or if the competency is not yet a strength, training can help. The knowledge and skill competencies are relatively easy to learn. Although behavioral competencies are more difficult and take longer to develop, growth in this area is also possible. The more competencies a facilitator possesses and the more effectively he uses those competencies, the better the performance, which directly affects the quality of the learning experience.

Noted

Noted

Additional factors external to the facilitator can also affect performance. However, these factors—including recognition and rewards, culture, and organization climate—are beyond the scope of this book.

Facilitator Selection

As you can see, there is a lot to being a good facilitator. It is so much more than just knowing the content or being able to present. To really make learning happen takes genuine skill. That point raises the question of how organizations select facilitators to guide the learning. You may be in a situation where you must select facilitators from within your organization or from a vendor organization. What factors should you consider?

Table 3–5. Facilitator Behavioral Competencies

|

Characteristic Grouping |

Behavioral Competencies |

|

Initiative |

1. Positions the learning experience with participants by building relationships and setting the climate 2. Positions the learning with participants to support the organization’s strategies and objectives 3. Makes extra efforts to ensure participant learning and use of that learning on the job by using real-world examples to focus questions, examples, and plans 4. Takes self-directed action to remove learning and transfer barriers in order to effectively and efficiently achieve learning outcomes |

|

Concern for Continuous Improvement |

1. Utilizes adult learning principles to ensure learning 2. Monitors ongoing participant learning by soliciting feedback and analyzing performance on assessments 3. Plans and monitors facilitation and online interaction to ensure efficient and effective use of time and greatest impact on learning |

|

Customer Service |

1. Acts as a learning consultant to participants 2. Implements instructional strategies relative to participant needs 3. Builds networks among participants to support classroom and online learning and transfer to the job |

|

Interpersonal Understanding |

1. Demonstrates and acts on an understanding of the collective concerns of the participants 2. Demonstrates and acts on an understanding of participants’ personal interests, concerns, and motivations 3. Seeks to understand the motivations of participants’ behavior |

|

Leading Others |

1. Promotes a spirit of cooperation among participants and between online participant and facilitator 2. Clarifies and communicates roles and expectations of facilitator and participants 3. Solicits the input of participants and leverages participant expertise through establishing collaborative relationships 4. Creates learner synergy through involvement in course instructional strategies 5. Recognizes and rewards the contribution of participants |

|

Developing Others |

1. Creates a learning environment (face-to-face, virtual classroom, or online) that fosters learning and transfer 2. Identifies job-related applications to course content 3. Contributes to individual, team, and corporate knowledge 4. Models development to support continuous learning 5. Provides coaching through multiple technologies to enhance learning |

|

Analytical and Problem Solving |

1. Implements a structured process of collecting course information and feedback 2. Gathers the relevant information and takes action to resolve a problem or issue within the learning experience |

|

Creativity and Innovation |

1. Uncovers opportunities for application of learning 2. Takes innovative action to maximize the effectiveness of a learning experience regardless of the learning environment 3. Implements creative instructional strategies |

|

Change Management |

1. Proactively recognizes situations where change in classroom (virtual and face-to-face or online) learning is needed and initiates appropriate action 2. Redirects efforts or adapts the approach in the face of changing course or participant requirements 3. Changes plans and acts in response to changing conditions or participant needs, rather than pursuing a single course of action 4. Ensures that the participants embrace the need for the new KSAs taught in the learning experience |

|

Risk Taking |

1. Takes appropriate risks to see new ideas, content, and instructional strategies accepted or implemented 2. Supports participants who take appropriate risks |

|

Communicating Effectively |

1. Makes effective verbal presentations (includes changing language or terminology to fit audience characteristics) 2. Reads and understands verbal and nonverbal and online behavior, and responds appropriately 3. Effectively uses nonverbal communication techniques 4. Recognizes the dynamics of online and virtual classroom communication |

|

Influencing |

1. Facilitates in such a way as to influence the participants to accept and use the new KSAs 2. Uses interpersonal and communication skills to gain acceptance of and commitment to course content and learning objectives 3. Gains commitment of participants by positioning the learning in terms of benefits that are meaningful to the participants 4. Builds trust and collaboration between the facilitator and participants, and among participants 5. Gains the cooperation and support of the participants |

|

Organizational Awareness |

1. Expresses the benefits and disadvantages of participants’ input using their business terminology 2. Acts as a catalyst for participants and their respective business units to improve performance through the use of the acquired KSAs 3. Recognizes and responds to organizational issues as they relate to the course content 4. Thinks organizationally and presents learning applications that address participants’ jobs and organizational needs 5. Demonstrates an understanding of the organization’s strategies, objectives, markets, products and services, informal political network, and so forth |

|

Personal Effectiveness Characteristics |

1. Represents accurately and completely the training organization to participants 2. Serves as a role model for others regarding appropriate business conduct and ethical principles 3. Keeps emotions under control when facing adversity 4. Interacts effectively with varying levels of participants with different backgrounds and perspectives and in different learning environments (online, virtual classroom, face-to-face) |

First, you may need to do some research. You want facilitators who are content experts and familiar with the use of technology in an online or virtual classroom environment, but who are also credible to your audience. Not all subject matter experts have the same credibility with your target audience. So, ask potential learners a few questions about the facilitator candidates to get a feel for what facilitator credibility means to them. For some learners, it’s experience; for others, it’s education; for still others, it’s something else.

Next, if you have the opportunity, see the potential facilitators in action. Try to observe how they develop the learning environment; their communication, presentation, and facilitation skills; how well they implement various learning activities; and how proficient they are in the use of media. For online training, you may want to observe their interactions and use of technology to enhance the learning.

Sometimes you’ll need to use someone from outside, perhaps a contractor, consultant, or someone from a vendor organization. When you use an external source, you must add to your assessment items such questions as:

• Is there compatibility of cultures?

• Will the facilitator candidates abide by your code of ethics and policies?

• Can they meet your delivery schedule?

• Can they demonstrate success within your industry and with your type of audience?

• Are the facilitators dedicated to your organization?

• Will they sign a nondisclosure agreement?

• Is it a cost-effective solution?

• Do the facilitators have subject matter expertise?

• Will they be credible to your audience?

• Do they know your organization and can they link the content to your organization?

• Are they skilled facilitators?

• Are they skilled in online or virtual classroom training?

Principles Underlying Facilitation of Learning

Professional, ethical, learner-centered, expert facilitation is critical to learners, organizations, and facilitators. The following principles are presented for your consideration. You are invited to make them your own.

1. Facilitated learning is learner centered, not facilitator centered.

2. The facilitator is in the learning experience with the learners; she is not merely an observer.

3. The facilitator’s goal is to make learning happen.

4. Learners get first crack at the learning as much as possible.

5. Adult learners have specific needs that facilitators must fulfill for learning to occur.

6. Facilitators create and use technology to ensure opportunities for learners to share their own experiences and expertise.

7. In a learning event, all participants are sources for learning; the facilitator is not the only source of expertise.

8. Facilitators protect and affirm ideas.

9. Facilitators are not performers. The facilitator’s job is to be interested, not interesting.

10. Facilitators encourage and support balanced participation in the learning group, whether in class (face-to-face or virtual), threaded discussions, discussion boards, or chat.

11. Facilitators create a comfortable and supportive environment in which learners can take risks.

12. Facilitators remove obstacles from the learning process.

Getting It Done

In this chapter, you learned a great deal about what it takes to be a facilitator. Exercise 3-1 will support your growth and development by allowing you to assess yourself in relation to facilitator roles.

Exercise 3-2 is a facilitation and presentation assessment tool that can be given to an observer to augment your judgment about your competencies. To use the facilitation and presentation assessment tool:

• Assign a weight to each behavior, totaling 100 points. Weights should reflect how each set of behaviors is valued by your organization.

• Select a skilled facilitator and have that person assess your skills using the assessment tool.

• Use this feedback to develop areas that are rated 2 or below.

Compare these results with the results of your self-assessment. After you and the observer have completed the assessments, you’ll have a road map for your development.

Exercise 3–1. Self-Assessment Role Inventory

This self-assessment is intended to help you reflect on your effectiveness regarding the various roles of a facilitator. Below are statements regarding the facilitator’s roles. Using the scale provided, indicate the extent to which you fulfill that dimension of a particular role. For areas rated 2 or below, identify specific actions you can take to improve yourself in that area.

0 = not at all

1 = to a very little extent

2 = to some extent

3 = to a great extent

4 = to a very great extent

Exercise 3-2. Facilitation Presentation Assessment

Below is a list of behaviors describing the demonstration of facilitation and presentation skills. As an assessor, assign a weight to each behavior, totaling 100. Weights should reflect how each behavior is valued by your organization.

Then use the following scale to indicate the extent to which the individual demonstrates the listed behaviors.

0 = not at all

1 = to a very little extent

2 = to some extent

3 = to a great extent

4 = to a very great extent