20. Automating Word

In This Chapter

Using Early Binding to Reference the Word Object

Using Late Binding to Reference the Word Object

Using the New Keyword to Reference the Word Application

Using the CreateObject Function to Create a New Instance of an Object

Using the GetObject Function to Reference an Existing Instance of Word

Controlling Form Fields in Word

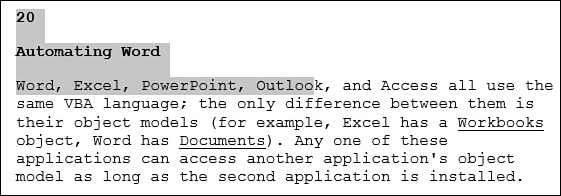

Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, and Access all use the same VBA language. The only difference is their object models. For example, Excel has a Workbooks object and Word has Documents. Any one of these applications can access another application’s object model as long as the second application is installed.

To access Word’s object library, Excel must establish a link to it by using either early binding or late binding. With early binding, the reference to the application object is created when the program is compiled. With late binding, the reference is created when the program is run.

This chapter is an introduction to accessing Word from Excel.

Note

Because this chapter does not review Word’s entire object model or the object models of other applications, refer to the VBA Object Browser in the appropriate application to learn about other object models.

Using Early Binding to Reference the Word Object

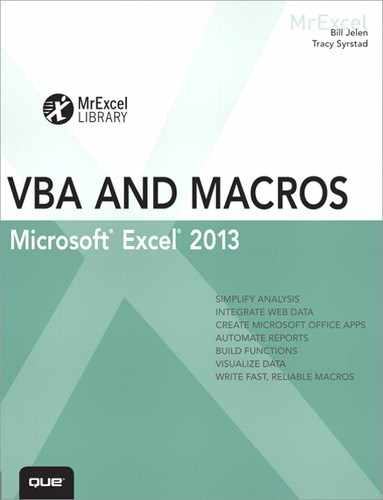

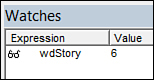

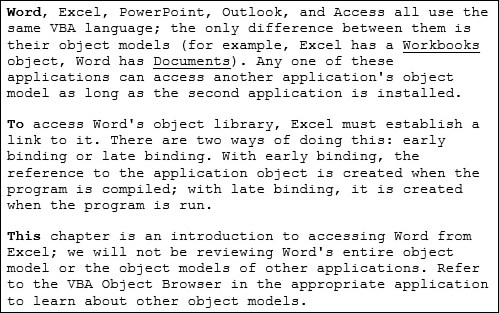

Code written with early binding executes faster than code with late binding. A reference is made to Word’s object library before the code is written so that Word’s objects, properties, and methods are available in the Object Browser. Tips such as a list of members of an object also appear, as shown in Figure 20.1.

Figure 20.1. Early binding allows access to the Word object’s syntax.

The disadvantage of early binding is that the referenced object library must exist on the system. For example, if you write a macro referencing Word 2013’s object library and someone with Word 2007 attempts to run the code, the program fails because the program cannot find the Word 2013 object library.

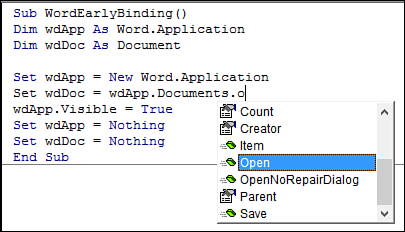

The object library is added through the VB Editor, as described here:

1. Select Tools, References.

2. Check Microsoft Word 15.0 Object Library in the Available References list (see Figure 20.2). If the object library is not found, Word is not installed. If another version is found in the list, such as 12.0, another version of Word is installed.

Figure 20.2. Select the object library from the Available References list.

3. Click OK.

After the reference is set, Word variables can be declared with the correct Word variable type, such as Document. However, if the object variable is declared As Object, this forces the program to use late binding. The following example creates a new instance of Word and opens an existing Word document from Excel. The declared variables, wdApp and wdDoc, are Word object types. wdApp is used to create a reference to the Word application in the same way the Application object is used in Excel. New Word.Application is used to create a new instance of Word. If you are opening a document in a new instance of Word, Word is not visible. If the application needs to be shown, it must be unhidden (wdApp.Visible = True). When the program is done, release the connection to Word by setting the object, wdApp, to Nothing.

Sub WordEarlyBinding()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Dim wdDoc As Document

Set wdApp = New Word.Application

Set wdDoc = wdApp.Documents.Open(ThisWorkbook.Path & _

"Automating Word.docx")

wdApp.Visible = True

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdDoc = Nothing

End Sub

Tip

Excel searches through the selected libraries to find the reference for the object type. If the type is found in more than one library, the first reference is selected. You can influence which library is chosen by changing the priority of the reference in the listing.

When the process is finished, it’s a good idea to set the object variables to Nothing and release the memory being used by the application, as shown here:

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdDoc = Nothing

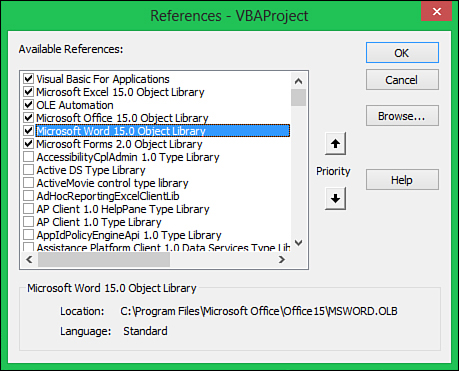

If the referenced version of Word does not exist on the system, an error message appears when the code is compiled. View the References list; the missing object is highlighted with the word MISSING (see Figure 20.3).

Figure 20.3. Excel won’t find the expected Word 2013 object library if the workbook is opened in Excel 2010.

If a previous version of Word is available, you can try running the program with that version referenced. Many objects are the same between versions.

Using Late Binding to Reference the Word Object

When using late binding, you are creating an object that refers to the Word application before linking to the Word library. Because you do not set up a reference beforehand, the only constraint on the Word version is that the objects, properties, and methods must exist. In the case where there are differences between versions of Word, the version can be verified and the correct object used accordingly.

The disadvantage of late binding is that because Excel does not know what is going on, it does not understand that you are referring to Word. This prevents the tips from appearing when referencing Word objects. In addition, built-in constants are not available. This means that when Excel is compiling, it cannot verify that the references to Word are correct. After the program is executed, the links to Word begin to build, and any coding errors are detected at that point.

The following example creates a new instance of Word, and then opens and makes visible an existing Word document. An object variable (wdApp) is declared and set to reference the application (CreateObject("Word.Application")). Other required variables are then declared (wdDoc), and the application object is used to refer these variables to Word’s object model. Declaring wdApp and wdDoc as objects forces the use of late binding. The program cannot create the required links to the Word object model until it executes the CreateObject function.

Sub WordLateBinding()

Dim wdApp As Object, wdDoc As Object

Set wdApp = CreateObject("Word.Application")

Set wdDoc = wdApp.Documents.Open(ThisWorkbook.Path & _

"Automating Word.docx")

wdApp.Visible = True

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdDoc = Nothing

End Sub

Using the New Keyword to Reference the Word Application

In the early-binding example, the keyword New was used to reference the Word application. The New keyword can be used only with early binding; it does not work with late binding. CreateObject or GetObject would also work, but New is best for this example. If an instance of the application is running and you want to use it, use the GetObject function instead.

Caution

If your code to open Word runs smoothly but you don’t see an instance of Word (and should because you code it to be Visible), open your Task Manager and look for the process WinWord.exe. If it exists, from the Immediate window in Excel’s VB Editor, type the following (which uses early binding):

Word.Application.Visible = True

If multiple instances of WinWord.exe are found, you need to make each instance visible and close the extra instance(s) of WinWord.exe.

Using the CreateObject Function to Create a New Instance of an Object

The CreateObject function was used in the late-binding example. However, this function can also be used in early binding. It is used to create a new instance of an object, in this case the Word application. CreateObject has a class parameter consisting of the name and type of the object to be created (Name.Type). For example, the examples in this chapter have shown you (Word.Application), in which Word is the Name and Application is the Type.

Using the GetObject Function to Reference an Existing Instance of Word

The GetObject function can be used to reference an instance of Word that is already running. It creates an error if no instance can be found.

GetObject’s two parameters are optional. The first parameter specifies the full path and filename to open, and the second parameter specifies the application program. The following example leaves off the application, allowing the default program, which is Word, to open the document:

Sub UseGetObject()

Dim wdDoc As Object

Set wdDoc = GetObject(ThisWorkbook.Path & "Automating Word.docx")

wdDoc.Application.Visible = True

'more code interacting with the Word document

Set wdDoc = Nothing

End Sub

This example opens a document in an existing instance of Word and ensures that the Word application’s Visible property is set to True. Note that to make the document visible, you have to refer to the application object (wdDoc.Application.Visible) because wdDoc is referencing a document rather than the application.

Note

Although the Word application’s Visible property is set to True, this code does not make the Word application the active application. In most cases, the Word application icon stays in the taskbar, and Excel remains the active application on the user’s screen.

The following example uses errors to learn whether Word is already open before pasting a chart at the end of a document. If Word is not open, it opens Word and creates a new document:

Sub IsWordOpen()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application 'early binding

ActiveChart.ChartArea.Copy

On Error Resume Next 'returns Nothing if Word isn't open

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

If wdApp Is Nothing Then

'since Word isn't open, open it

Set wdApp = GetObject("", "Word.Application")

With wdApp

.Documents.Add

.Visible = True

End With

End If

On Error GoTo 0

With wdApp.Selection

.EndKey Unit:=wdStory

.TypeParagraph

.PasteSpecial Link:=False, DataType:=wdPasteOLEObject, _

Placement:=wdInLine, DisplayAsIcon:=False

End With

Set wdApp = Nothing

End Sub

Using On Error Resume Next forces the program to continue even if it runs into an error. In this case, an error occurs when we attempt to link wdApp to an object that does not exist. wdApp will have no value. The next line, If wdApp Is Nothing Then, takes advantage of this and opens an instance of Word, adding an empty document and making the application visible. Use On Error Goto 0 to return to normal VBA error-handling behavior.

Tip

Note the use of empty quotes for the first parameter in GetObject("", "Word.Application"). This is how to use the GetObject function to open a new instance of Word.

Using Constant Values

The preceding example used constants that are specific to Word such as wdPasteOLEObject and wdInLine. When you are programming using early binding, Excel helps by showing these constants in the tip window.

With late binding, these tips will not appear. So what can you do? You might write your program using early binding, and then change it to late binding after you compile and test the program. The problem with this method is that the program will not compile because Excel does not recognize the Word constants.

The words wdPasteOLEObject and wdInLine are for your convenience as a programmer. Behind each of these text constants is the real value that VBA understands. The solution to this is to retrieve and use these real values with your late binding program.

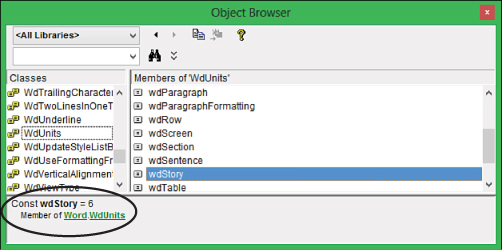

Using the Watch Window to Retrieve the Real Value of a Constant

One way to retrieve the value is to add a watch for the constants. Then, step through your code and check the value of the constant as it appears in the Watch window, as shown in Figure 20.4.

Figure 20.4. Use the Watch window to get the real value behind a Word constant.

Note

See “Querying by Using a Watch Window” in Chapter 2, “This Sounds Like BASIC, so Why Doesn’t It Look Familiar?” for more information on using the Watch window.

Using the Object Browser to Retrieve the Real Value of a Constant

Another way to retrieve the value is to look up the constant in the Object Browser. However, you need the Word library set up as a reference to use this method. To set up the Word library, right-click the constant and select Definition. The Object Browser opens to the constant and shows the value in the bottom window, as shown in Figure 20.5.

Figure 20.5. Use the Object Browser to get the real value behind a Word constant.

Tip

You can set up the Word reference library to be accessed from the Object Browser. However, you do not have to set up your code with early binding. In this way, the reference is at your fingertips, but your code is still late binding. Turning off the reference library is just a few clicks away.

Replacing the constants in the earlier code example with their real values would look like this:

With wdApp.Selection

.EndKey Unit:=6

.TypeParagraph

.PasteSpecial Link:=False, DataType:=0, Placement:=0, DisplayAsIcon:=False

End With

However, what happens a month from now when you return to the code and you try to remember what those numbers mean? The solution is up to you. Some programmers add comments to the code referencing the Word constant. Other programmers create their own variables to hold the real value and use those variables in place of the constants, like this:

Const xwdStory As Long = 6

Const xwdPasteOLEObject As Long = 0

Const xwdInLine As Long = 0

With wdApp.Selection

.EndKey Unit:=xwdStory

.TypeParagraph

.PasteSpecial Link:=False, DataType:=xwdPasteOLEObject, _

Placement:=xwdInLine, DisplayAsIcon:=False

End With

Understanding Word’s Objects

Word’s macro recorder can be used to get a preliminary understanding of the Word object model. However, much as with Excel’s macro recorder, the results will be long-winded. Keep this in mind and use the recorder to lead you toward the objects, properties, and methods in Word.

Caution

The macro recorder is limited in what it allows you to record. The mouse cannot be used to move the cursor or select objects, but there are no limits in doing so with the keyboard.

The following example is what the Word macro recorder produces when adding a new, blank document from File, New, Blank Document:

Documents.Add Template:="Normal", NewTemplate:=False, DocumentType:=0

Making this more efficient in Word produces this:

Documents.Add

Template, NewTemplate, and DocumentType are all optional properties that the recorder includes but that are not required unless you need to change a default property or ensure that a property is what you require.

To use the same line of code in Excel, a link to the Word object library is required, as you learned earlier. After that link is established, an understanding of Word’s objects is all you need. The next section is a review of some of Word’s objects—enough to get you off the ground. For a more detailed listing, refer to the object model in Word’s VB Editor.

Document Object

Word’s Document object is equivalent to Excel’s Workbook object. It consists of characters, words, sentences, paragraphs, sections, and headers/footers. It is through the Document object that methods and properties affecting the entire document, such as printing, closing, searching, and reviewing, are accomplished.

Create a New Blank Document

To create a blank document in an existing instance of Word, use the Add method as shown next. We already learned how to create a new document when Word is closed—refer to GetObject and CreateObject.

Sub NewDocument()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

wdApp.Documents.Add

'any other Word code you need here

Set wdApp = Nothing

End Sub

This example opens a new, blank document that uses the default template. To create a new document that uses a specific template, use this:

wdApp.Documents.Add Template:="Memo (Contemporary design).dotx"

This creates a new document that uses the Contemporary Memo template. Template can be either the name of a template from the default template location or the file path and name.

Open an Existing Document

To open an existing document, use the Open method. Several parameters are available, including Read Only and AddtoRecentFiles. The following example opens an existing document as Read Only, and prevents the file from being added to the Recent File List under the File menu:

wdApp.Documents.Open _

Filename:="C:Excel VBA 2013 by Jelen & SyrstadChapter 8 - Arrays.docx", _

ReadOnly:=True, AddtoRecentFiles:=False

Save Changes to a Document

After you have made changes to a document, most likely you will want to save it. To save a document with its existing name, use this:

wdApp.Documents.Save

If you use the Save command with a new document without a name, nothing will happen. To save a document with a new name, you must use the SaveAs method instead:

wdApp.ActiveDocument.SaveAs _

"C:Excel VBA 2013 by Jelen & SyrstadMemoTest.docx"

SaveAs requires the use of members of the Document object, such as ActiveDocument.

Close an Open Document

Use the Close method to close a specified document or all open documents. By default, a Save dialog appears for any documents with unsaved changes. You can use the SaveChanges argument to change this. To close all open documents without saving changes, use this code:

wdApp.Documents.Close SaveChanges:=wdDoNotSaveChanges

To close a specific document, you can close the active document or you can specify a document name:

wdApp.ActiveDocument.Close

or

wdApp.Documents("Chapter 8 - Arrays.docx").Close

Print a Document

Use the PrintOut method to print part or all of a document. To print a document with all the default print settings, use this:

wdApp.ActiveDocument.PrintOut

By default, the print range is the entire document, but you can change this by setting the Range and Pages arguments of the PrintOut method. For example, to print only page 2 of the active document, use this:

wdApp.ActiveDocument.PrintOut Range:=wdPrintRangeOfPages, Pages:="2"

Selection Object

The Selection object represents what is selected in the document, such as a word, a sentence, or the insertion point. It also has a Type property that returns the type that is selected, such as wdSelectionIP, wdSelectionColumn, and wdSelectionShape.

Navigating with HomeKey and EndKey

The HomeKey and EndKey methods are used to change the selection; they correspond to using the Home and End keys, respectively, on the keyboard. They have two parameters: Unit and Extend. Unit is the range of movement to make, to either the beginning (Home) or end (End) of a line (wdLine), document (wdStory), column (wdColumn), or row (wdRow). Extend is the type of movement: wdMove moves the selection, and wdExtend extends the selection from the original insertion point to the new insertion point.

To move the cursor to the beginning of the document, use this code:

wdApp.Selection.HomeKey Unit:=wdStory, Extend:=wdMove

To select the document from the insertion point to the end of the document, use this code:

wdApp.Selection.EndKey Unit:=wdStory, Extend:=wdExtend

Inserting Text with TypeText

The TypeText method is used to insert text into a Word document. User settings, such as the ReplaceSelection setting, can affect what happens when text is typed into the document when text is selected. The following example first makes sure that the setting for overwriting selected text is turned on. Then it selects the second paragraph (using the Range object described in the next section) and overwrites it.

Sub InsertText()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Dim wdDoc As Document

Dim wdSln As Selection

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

Set wdDoc = wdApp.ActiveDocument

wdDoc.Application.Options.ReplaceSelection = True

wdDoc.Paragraphs(2).Range.Select

wdApp.Selection.TypeText "Overwriting the selected paragraph."

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdDoc = Nothing

End Sub

Range Object

The Range object uses the following syntax:

Range(StartPosition, EndPosition)

The Range object represents a contiguous area or areas in the document. It has a starting character position and an ending character position. The object can be the insertion point, a range of text, or the entire document including nonprinting characters such as spaces or paragraph marks.

The Range object is similar to the Selection object, but in some ways it is better. For example, the Range object requires less code to accomplish the same tasks, and it has more capabilities. In addition, it saves time and memory because the Range object does not require Word to move the cursor or highlight objects in the document to manipulate them.

Define a Range

To define a range, enter a starting and ending position, as shown in this code segment:

Sub RangeText()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Dim wdDoc As Document

Dim wdRng As Word.Range

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

Set wdDoc = wdApp.ActiveDocument

Set wdRng = wdDoc.Range(0, 50)

wdRng.Select

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdDoc = Nothing

Set wdRng = Nothing

End Sub

Figure 20.6 shows the results of running this code. The first 50 characters are selected, including nonprinting characters such as paragraph returns.

Figure 20.6. The Range object selects everything in its path.

The range was selected (wdRng.Select) for easier viewing. It is not required that the range be selected to be manipulated. For example, to delete the range, do this:

wdRng.Delete

The first character position in a document is always zero, and the last is equivalent to the number of characters in the document.

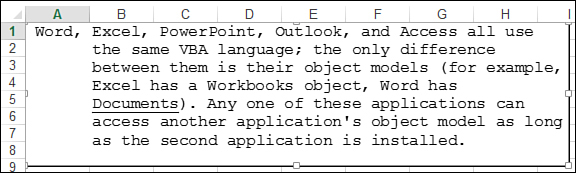

The Range object also selects paragraphs. The following example copies the third paragraph in the active document and pastes it in Excel. Depending on how the paste is done, the text can be pasted into a text box (see Figure 20.7) or into a cell:

Sub SelectSentence()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Dim wdRng As Word.Range

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

With wdApp.ActiveDocument

If .Paragraphs.Count >= 3 Then

Set wdRng = .Paragraphs(3).Range

wdRng.Copy

End If

End With

'This line pastes the copied text into a text box

'because that is the default PasteSpecial method for Word text

Worksheets("Sheet2").PasteSpecial

'This line pastes the copied text in cell A1

Worksheets("Sheet2").Paste Destination:=Worksheets("Sheet2").Range("A1")

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdRng = Nothing

End Sub

Figure 20.7. Paste Word text into an Excel text box.

Format a Range

After a range is selected, formatting can be applied to it (see Figure 20.8). The following program loops through all the paragraphs of the active document and applies bold to the first word of each paragraph:

Sub ChangeFormat()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Dim wdRng As Word.Range

Dim count As Integer

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

With wdApp.ActiveDocument

For count = 1 To .Paragraphs.Count

Set wdRng = .Paragraphs(count).Range

With wdRng

.Words(1).Font.Bold = True

.Collapse

End With

Next count

End With

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdRng = Nothing

End Sub

Figure 20.8. Format the first word of each paragraph in a document.

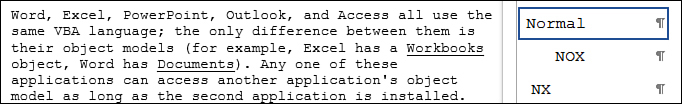

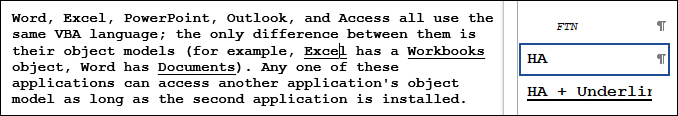

A quick way of changing the formatting of entire paragraphs is to change the style (see Figures 20.9 and 20.10). The following program finds the paragraph with the Normal style and changes it to HA:

Sub ChangeStyle()

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Dim wdRng As Word.Range

Dim count As Integer

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

With wdApp.ActiveDocument

For count = 1 To .Paragraphs.Count

Set wdRng = .Paragraphs(count).Range

With wdRng

If .Style = "Normal" Then

.Style = "HA"

End If

End With

Next count

End With

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdRng = Nothing

End Sub

Figure 20.9. Before: A paragraph with the Normal style needs to be changed to the HA style.

Figure 20.10. After: Apply styles with code to change paragraph formatting quickly.

Bookmarks

Bookmarks are members of the Document, Selection, and Range objects. They can help make it easier to navigate around Word. Instead of having to choose words, sentences, or paragraphs, use bookmarks to manipulate sections of a document swiftly.

Note

You are not limited to using only existing bookmarks. Instead, you can create bookmarks using code.

Bookmarks appear as gray I-bars in Word documents. In Word, go to File, Options, Advanced, Show Document Contents and select Show Bookmarks to turn on bookmarks.

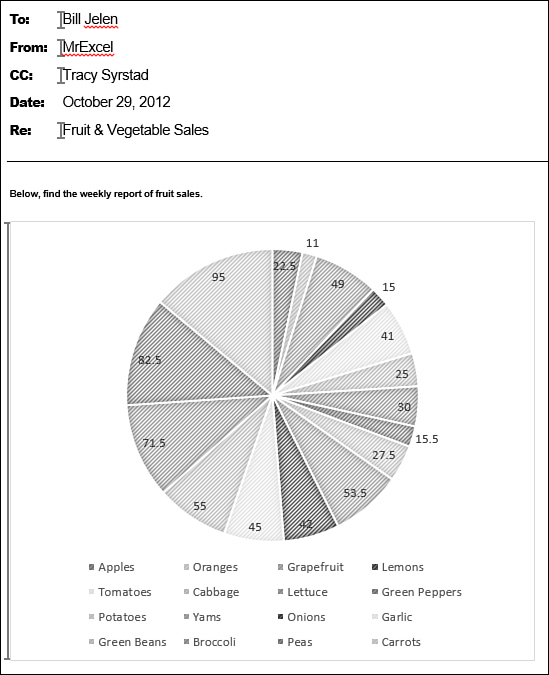

After you have set up bookmarks in a document, you can use the bookmarks to move quickly to a range to insert text or other items, such as charts. The following code automatically inserts text and a chart after bookmarks that were previously set up in the document. Figure 20.11 shows the results.

Sub FillInMemo()

Dim myArray()

Dim wdBkmk As String

Dim wdApp As Word.Application

Dim wdRng As Word.Range

myArray = Array("To", "CC", "From", "Subject", "Chart")

Set wdApp = GetObject(, "Word.Application")

'insert text

Set wdRng = wdApp.ActiveDocument.Bookmarks(myArray(0)).Range

wdRng.InsertBefore ("Bill Jelen")

Set wdRng = wdApp.ActiveDocument.Bookmarks(myArray(1)).Range

wdRng.InsertBefore ("Tracy Syrstad")

Set wdRng = wdApp.ActiveDocument.Bookmarks(myArray(2)).Range

wdRng.InsertBefore ("MrExcel")

Set wdRng = wdApp.ActiveDocument.Bookmarks(myArray(3)).Range

wdRng.InsertBefore ("Fruit & Vegetable Sales")

'insert chart

Set wdRng = wdApp.ActiveDocument.Bookmarks(myArray(4)).Range

Worksheets("Fruit Sales").ChartObjects("Chart 1").Copy

wdRng.PasteAndFormat Type:=wdPasteOLEObject

wdApp.Activate

Set wdApp = Nothing

Set wdRng = Nothing

End Sub

Figure 20.11. Use bookmarks to enter text or charts into a Word document.

Controlling Form Fields in Word

You have seen how to modify a document by inserting charts and text, modifying formatting, and deleting text. However, a document might contain other items such as controls that you can modify.

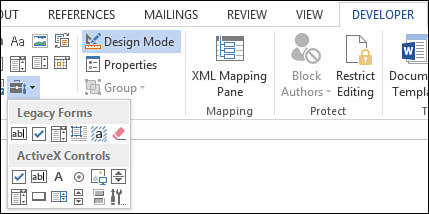

For the following example, a template, New Client.dotx, was created consisting of text and bookmarks. The bookmarks are placed after the Name and Date fields. Form Field check boxes were also added. The controls are found under Legacy forms in the Controls section of the Developer tab in Word, as shown in Figure 20.12. Notice in the code sample that follows that the check boxes have all been renamed so they make more sense. For example, one bookmark was renamed chk401k from Checkbox5. To rename a bookmark, right-click the check box, select Properties, and type a new name in the Bookmark field.

Figure 20.12. You can use the Form Fields found under the Legacy Tools to add check boxes to a document.

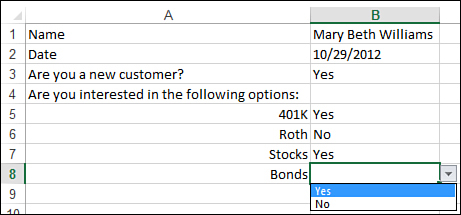

The questionnaire was set up in Excel, allowing the user to enter free text in B1 and B2, but setting up data validation in B3 and B5:B8, as shown in Figure 20.13.

Figure 20.13. Create an Excel sheet to collect your data.

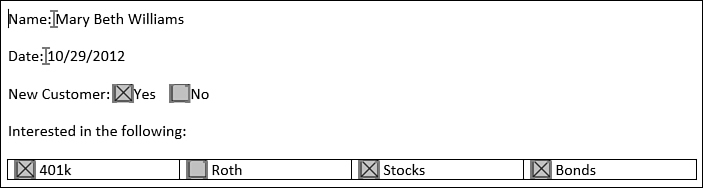

The code goes into a standard module. The name and date go straight into the document. The check boxes use logic to verify whether the user selected Yes or No to confirm whether the corresponding check box should be checked. Figure 20.14 shows a sample document that has been completed.

Sub FillOutWordForm()

Dim TemplatePath As String

Dim wdApp As Object

Dim wdDoc As Object

'Open the template in a new instance of Word

TemplatePath = ThisWorkbook.Path & "New Client.dotx"

Set wdApp = CreateObject("Word.Application")

Set wdDoc = wdApp.documents.Add(Template:=TemplatePath)

'Place our text values in document

With wdApp.ActiveDocument

.Bookmarks("Name").Range.InsertBefore Range("B1").Text

.Bookmarks("Date").Range.InsertBefore Range("B2").Text

End With

'Using basic logic, select the correct form object

If Range("B3").Value = "Yes" Then

wdDoc.formfields("chkCustYes").CheckBox.Value = True

Else

wdDoc.formfields("chkCustNo").CheckBox.Value = True

End If

With wdDoc

If Range("B5").Value = "Yes" Then .Formfields("chk401k").CheckBox.Value = _

True

If Range("B6").Value = "Yes" Then .Formfields("chkRoth").CheckBox.Value _

= True

If Range("B7").Value = "Yes" Then .Formfields("chkStocks"). _

CheckBox.Value = True

If Range("B8").Value = "Yes" Then .Formfields("chkBonds"). _

CheckBox.Value = True

End With

wdApp.Visible = True

ExitSub:

Set wdDoc = Nothing

Set wdApp = Nothing

End Sub

Figure 20.14. Excel can control Word’s form fields and help automate filling out documents.

Next Steps

Chapter 19, “Text File Processing,” showed you how to read from a text file to import data from another system. In this chapter, you learned how to connect to another Office program and access its object module. In Chapter 21, “Using Access as a Back End to Enhance Multiuser Access to Data,” you connect to an Access database and learn about writing to Access Multidimensional Database (MDB) files. Compared to text files, Access files are faster, indexable, and allow multiuser access to data.