Eastern Europe Regional Bloc: CEE and CIS

The future economic growth of Eastern European countries will depend largely on the European Union, which received 80 percent of Eastern Europe’s exported goods in 2008.

—Alejandro Foxley

Introduction

As discussed in earlier chapters, the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE)1 bloc is a generic term that defines the group of countries in central, south-east, northern, and eastern Europe, commonly meaning former communist states in Europe. It is in use since the collapse of the Iron Curtain2 in 1989 to 1990, when more than 20 nations emerged from the isolation that had largely hidden them, and its citizens, from the rest of the world for more than 4 decades. As argued by Lerman, Csaki, and Feder (2004), in each of these former Soviet states, remnants of tradition and economic organization have prevented them from stepping out, beyond the curtain and onto the world stage. Nonetheless, some have been extremely successful.

The CEE bloc of countries include all the eastern bloc countries west of the post-World War II border with the former Soviet Union. The Eastern Bloc was the name used by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-affiliated countries for the former communist states of CEE, which generally included the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact.3 The terms Communist Bloc and Soviet Bloc were also used to denote groupings of states aligned with the Soviet Union, although these terms might include states outside CEE. Figure 3.1 depicts a map of countries that declared themselves to be socialist states under the Marxist–Leninist or Maoist definition, in other words communist states, between 1979 and 1983. This period marked the greatest territorial extent of communist states.4

In addition, the CEE bloc also includes the independent states in former Yugoslavia, which actually were not considered part of the eastern bloc, and the three Baltic States—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, which chose not to join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) with the other 12 former republics of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR5).

Figure 3.1 Countries that declared to be socialist or communist between 1979 and 1983

Source: Busky (2000).

Recently, during the summer 2015, the Russian government publicly stated to the world that the Soviet government who gave away the Baltics was illegitimate and its decisions were illegal. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office launched at the time an improbable but nonetheless serious investigation into the legality of the independence of the three Baltic countries. The Russian trial on the legal status of their independence is based on the idea that the interim Soviet government in place in 1991 was illegitimate and its decisions therefore are also illegitimate.

Since then, the three countries, whose national cultures are clearly northern European rather than Slavic have been outstanding success stories, implementing economic reforms, and gaining membership of NATO, the European Union (EU), and the United Nations. The Baltic states are located in the northeastern region of Europe, on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, bounded on the west and north by the Baltic Sea, which gives the region its name, on the east by Russia, on the southeast by Belarus, and on the southwest by Poland and an exclave of Russia. Figure 3.2 depicts a map of the location of the Baltic states.

Transition Countries

Both the CEE and the CIS country blocs are considered transition countries in Europe. These are transition economies that are undergoing a change from a centrally planned economy to a market economy.6 These economies are undertaking a set of structural transformations intended to develop market-based institutions. These include economic liberalization, where prices are set by market forces rather than by a central planning organization.

In addition, a major effort is placed to remove trade barriers, while pushing to privatize state-owned enterprises and resources. State and collectively run enterprises are restructured as businesses, and a financial sector is created to facilitate macroeconomic stabilization and the movement of private capital.7 This process is not only being applied in eastern bloc countries of Europe, but has also been applied in China, the former Soviet Union, and some other emerging and frontier market countries.

Figure 3.2 Location of the Baltic states in Europe

Source: UN (1995).

The transition process is usually characterized by the change and creation of institutions, particularly private enterprises, changes in the role of the state, thereby, the creation of fundamentally different governmental institutions, and the promotion of private-owned enterprises, markets and independent financial institutions.8 In essence, one transition mode is the functional restructuring of state institutions from being a provider of growth to an enabler, with the private sector as its engine. Due to the different initial conditions during the emerging process of the transition from planned economics to market economics, countries uses different transition model. Countries like China and Vietnam adopted a gradual transition mode; however, Russia and some other east European countries, such as the former Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia, used a more aggressive and quicker paced model of transition. These transition countries in Europe are thus classified today into two political-economic entities: CEE and CIS.

The CEE Bloc

As mentioned earlier, the CEE countries are a bloc of countries comprising Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, and the three Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. But the CEE countries are further subdivided by their accession status to the EU.

The eight first-wave accession countries that joined the EU in May 2004 includes Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, and Slovenia. The two second-wave accession countries that joined in January 2007 include Romania and Bulgaria. The third-wave accession country that joined the EU in July 2013 includes Croatia. According to the World Bank,9 “the transition is over” for the 10 countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007, which can be also understood as all countries of the eastern bloc.10

After 15 years of economic boom in central eastern Europe, during which the countries in the region enjoyed growth levels twice as high as in western Europe, the development came to an abrupt halt as the effects of the global financial crisis that started in 2007. Several states in CEE were struck hard as many of these countries were in a state of rapid development fuelled by foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows when the crisis hit.

More recently, the CEE countries have been showing signs of recovery, some faster than others, reading themselves once again for the numerous opportunities for future economical development. One of the main drivers of economic growth is the regions’ great location, opened to a market of over 200 million consumers. In addition, the region enjoys a large qualitative labor force at relatively low costs, which provides an inviting atmosphere for foreign investments and business development. There are still plenty of unexploited opportunities in CEE, whether in its huge surfaces of arable land, in its strong skills in technical and technological areas, numerous investment incentives, or unique touristic destinations. Figure 3.3 shows a map of the CEE country bloc.

As a whole, the CEE includes the following former socialist countries, which extend east from the border of Germany and south from the Baltic Sea to the border with Greece: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia. The fundamental conditions for growth in this region are strong. This is especially so in the reform-oriented countries that had introduced business friendly politics and low tax rates in the run-up of their EU accession. In effect, several countries such as Poland and Czech Republic, the two largest economies in the region, as well as Slovakia handled the global financial crisis surprisingly well. Even the countries hit hardest like Hungary will most likely turn the crisis into an upswing in a few years time. The growth potential of these countries is also intensified by the integration of CEE countries into the eurozone and Schengen area.11 Please refer to Appendix A for a brief scanning of the CEE countries.

Figure 3.3 The CEE country bloc

Source: Stepmap.de

The CIS Bloc

The CIS, also known as the Russian Commonwealth, is a regional bloc of countries formed during the breakup of the Soviet Union, whose participating countries are some former Soviet republics. The CIS is a loose association of countries. Although the CIS has few supranational powers, it is aimed at being more than a purely symbolic organization, nominally possessing coordinating powers in the realm of trade, finance, lawmaking, and security. It has also promoted cooperation on cross-border crime prevention.

The CIS was established on December 8, 1991, through the Belovezh Accords,12 which also brought an end to the Soviet Union. Leaders from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus signed these accords and then later that month, on the 21st, through the Alma-Ata Protocols,13 Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, for a total of 11 countries, also agreed to join the CIS. Georgia joined the CIS in December 1993, bringing the total membership to 12 states (the Baltic republics of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia never joined). Figure 3.4 illustrates the geographic location of the CIS bloc.

Figure 3.4 The 12 CIS bloc countries

Source: interopp.org.

The organization had several goals, including coordination of members’ foreign and security policies, development of a common economic space, fostering human rights and interethnic concord, maintenance of the military assets of the former USSR, creation of shared transportation and communications networks, environmental security, regulation of migration policy, and efforts to combat organized crime. The CIS had a variety of institutions through which it attempted to accomplish these goals: Council of Heads of State, Council of Heads of Government, Council of Foreign Ministers, Council of Defense Ministers, an inter-parliamentary assembly, Executive Committee, Anti-Terrorism Task Force, and the Interstate Economic Committee of the Economic Union.

Although in a sense the CIS was designed to replace the Soviet Union, it was not and is not a separate state or country. Rather, the CIS is an international organization designed to promote cooperation among its members in a variety of fields. Its headquarters are in Minsk, Belarus. Over the years, its members have signed dozens of treaties and agreements, and some hoped that it would ultimately promote the dynamic development of ties among the newly independent post-Soviet states. By the late 1990s, however, the CIS lost most of its momentum and was victimized by internal rifts, becoming, according to some observers, largely irrelevant and powerless.14

From its beginning, the CIS had two main purposes. The first was to promote what was called a “civilized divorce” among the former Soviet states. Many feared the breakup of the Soviet Union would lead to political and economic chaos, if not the outright conflict over borders. The earliest agreements of the CIS, which provided for recognition of borders, protection of ethnic minorities, maintenance of a unified military command, economic cooperation, and periodic meetings of state leaders, arguably helped to maintain some semblance of order in the region, although one should note that the region did suffer some serious conflicts, of note, the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and the civil conflicts in Tajikistan, Moldova, and Georgia.

The second purpose of the CIS was to promote integration among the newly independent states. On this score, the CIS had not succeeded. The main reason is that while all parties had a common interest in peacefully dismantling the old order, there has been no consensus among these states as to what, if anything, should replace the Soviet state. Moreover, the need to develop national political and economic systems took precedence in many states, dampening enthusiasm for any project of reintegration. CIS members have also been free to sign or not sign agreements as they see fit, creating a hodgepodge of treaties and obligations among CIS states.

One of the clearest failures of the CIS has been on the economic front. Although the member states pledged cooperation, things began to break down early on. By 1993, the ruble zone collapsed, with each state issuing its own currency. In 1993 and 1994, 11 CIS states ratified a Treaty on an Economic Union, in which Ukraine joined as an associate member. A free-trade zone was proposed in 1994, but by 2002 it still had not yet been fully established. In 1996 four states, including Russia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, created a Customs Union,15 but others refused to join. All these efforts were designed to increase trade, but, due to a number of factors, trade among CIS countries has lagged behind the targeted figures. More broadly speaking, economic cooperation has suffered because states had adopted economic reforms and programs with little regard for the CIS and have put more emphasis on redirecting their trade to neighboring European or Asian states.

Cooperation in military matters fared little better. The 1992 Tashkent Treaty on Collective Security16 was ratified by merely six states. While CIS peacekeeping troops were deployed to Tajikistan and Abkhazia, a region of Georgia, critics viewed these efforts as Russia’s attempts to maintain a sphere of influence in these states. As the “Monroeski Doctrine”17 took hold in Moscow, which asserted special rights for Russia on post-Soviet territory, and Russia used its control over energy pipelines to put pressure on other states, there was a backlash by several states against Russia, which weakened the CIS. After September 11, 2001, the CIS created bodies to help combat terrorism, and some hoped that this might bring new life to the organization.

Appendix B provides a brief country scanning of the CIS member states.

Economic Challenges

According to Marek Dabrowski,18 a scholar and professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow and fellow at CASE (Centre for Social and Economic Research) in Warsaw, Poland, the period of fast economic growth and relative macroeconomic stability in the CIS seems to be over. The collapse of the Russian ruble, expected recession in Russia, the stronger U.S. dollar, and lower commodity prices have negatively affected the entire region through trade, labor remittance, and financial-market channels, resulting in negative expectations and leading to either substantial depreciation of national currencies, or decline in countries’ international reserves, or both. This means that the EU’s entire eastern neighborhood faces serious economic, social, and political challenges coming from weaker currencies, higher inflation, decreasing export revenues and labor remittances, net capital outflows, and stagnating or declining gross domestic product (GDP).

The currency crisis started in Russia and Ukraine during 2014 as a result of the combination of global, regional, and country-specific factors. Among the latter, the ongoing conflicts between the two countries and the associated U.S. and EU sanctions against Russia have played the most prominent role. At the end of 2014 and in early 2015, the currency crisis spread to Russia and Ukraine’s neighbors.

The gradual depreciation of the ruble against both the euro and U.S. dollar, as depicted in Figure 3.5, started in November 2013, before the Russian–Ukraine conflict emerged and when oil prices were high. The depreciation intensified in March and April 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the first round of U.S. and EU sanctions against Russia. Between May and July 2014, the ruble partly regained its previous value.

Figure 3.5 Ruble exchange rate against the euro and dollar, 2013–2015

Source: Central Bank of Russia, www.cbr.ru/eng/currency_base/dynamics.aspx

The depreciation trend, however, returned in the second half of July 2014. Its pace increased in October with a culmination in mid-December 2014, as also depicted in Figure 3.5. After a massive intervention on the foreign exchange market and the adoption by Russia of other anti-crisis measures, the situation stabilized for a while. However, depreciation started again in January 2015, boosted by Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s downgrading of Russia’s credit rating, and the subsequent escalation of the Donbass19 conflict in Ukraine.

Figure 3.6 Russia’s international reserves in $ billions, 2013–2014

Source: Central Bank of Russia, www.cbr.ru/eng/hd_base/default.aspx?Prtid=mrrf_m

Cumulatively, between the end of November 2013 and end of 2014, Russia lost $130 billion of its international reserves in the region, as shown in Figure 3.6, which resulted from a large-scale capital outflow estimated to exceed $150 billion in 2014. Nevertheless, Russia continues to have a sizeable current account surplus. In the first half of January 2015, the reserves decreased further by about $7 billion.

Economies at War

This currency crisis challenges in Russia and in the CIS (more on this in the next section) are in fact a result of a much bigger threat to the global economy, often dubbed by economists at large as a result of currency wars. For the past few years, at least since 2010, government officials from the G7 economies have been very concerned with the potential escalation of a global economic war. Not a conventional war, with fighter jets, bullets, and bombs, but instead, a “currency war.” Finance ministers and central bankers from advanced economies worry that their peers in the G20, which also include several emerging economies, may devalue their currencies to boost exports and grow their economies at their neighbors’ expense.

Brazil led the charge, being the first emerging economy to accuse the United States of instigating a currency war in 2010, when the U.S. Federal Reserve bought piles of bonds with newly created money. From a Chinese perspective, with the world’s largest holdings of U.S. dollar reserves, a U.S.-lead currency war based on dollar debasement is an American act of default to its foreign creditors, no matter how you disguise it. So far, the Chinese have been more diplomatic, but their patience is wearing thin.

These two countries are not alone, as depicted in Figure 3.7, several other emerging markets, such as Saudi Arabia, Korea, Russia, Turkey, and Taiwan have also been impacted by a weak dollar. That “quantitative easing” (QE) made investors flood emerging markets with hot money in search of better returns, which consequently lifted their exchange rates. But Brazil was not alone, as Japan’s Shinzo Abe, the new prime minister, has also reacted to the QEs in the United States and pledged bold stimulus to restart growth and vanquish deflation in the country.

As advanced economies, like the first three largest world economies— the United States, China, and Japan, respectively—try to kick-start their sluggish economies with ultralow interest rates and sprees of money printing, they are putting downward pressure on their currencies. The loose monetary policies are primarily aimed at stimulating domestic demand. But their effects spill over into the currency world.

Figure 3.7 Emerging market currencies inflated by weak dollar

Source: Thompson Reuters Datastream.

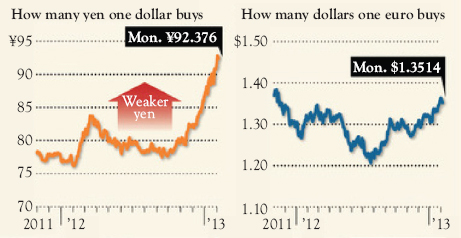

Japan is facing charges that it is trying first and foremost to lower the value of its currency, the yen, to stimulate its economy and get the edge over other countries. The new government is trying to get Japan, which has been in recession, moving again after a two-decade bout of stagnant growth and deflation. Hence, it has embarked on an economic course that it hopes will finally jump-start the economy. The government pushed the Bank of Japan to accept a higher inflation target, which has triggered speculation that the bank will create more money. The prospect of more yen in circulation has been the main reason behind the yen’s recent falls to a 21-month low against the dollar and a near three-year record against the euro.

Ever since Shinzo Abe called for a weaker yen to bolster exports, the currency has fallen by 16 percent against the dollar and 19 percent against the euro. As the yen falls, its exports become cheaper, and those of Asian neighbors, South Korea, and Taiwan, as well as those countries further afield in Europe, become relatively more expensive. As depicted in Figure 3.8, central banks in the United States and Japan have flooded their economies with liquidity since mid-2012 to 2013, causing the yen and the dollar to weaken against other major currencies.

In our opinion, common sense could prevail, putting an end to the dangerous game of beggar (and blame) thy neighbor. After all, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was created to prevent such races to the bottom, and should try to broker a truce among foreign exchange competitors. The critical issues in the United States, as well as China and Japan, stem from minimally a blatantly ineffective public policy, but over-ridingly a failed and destructive economic policy. These policy errors are directly responsible for the currency war clouds, now looming overhead.20

Figure 3.8 Central banks in the United States and Japan have flooded their economies with liquidity

Source: WSJ Market Data Group.

So far, Europe has felt the impact of the falling yen the most. At the height of the eurozone’s financial crisis in 2012, the euro was worth $1.21, which was potentially benefitting big exporters like BMW, AUDI, Mercedes, or Airbus. However, at the time of these writing, December 2013, the euro is at $1.38 even though the eurozone is still the laggard of the world economy.

Across the 17-strong euro countries, a recovery has got underway following a double-dip recession lasting 18 months, but it is a feeble one. For 2013, as the whole GDP will still continue to fall by 0.4 percent (after declining by 0.6 percent in 2012), it is expected to rise by 1.1 percent in 2014.21 A rise in the value of euro, which is also partly to do with the diminishing threat of a collapse of the currency, will do little to help companies in the eurozone—and will hardly help getting it growing again.

Chinese policymakers reject the conventional thinking proposed by advanced economies. How about the yen’s extraordinary rise over the last 40 years, from yen 360 against the dollar at the beginning of the 1970s to about yen 102 today?22 Not to mention that despite this huge appreciation, Japan’s current account surplus has only got bigger, not smaller. They could also argue that the United States’ prescription for China’s economic rebalancing, a stronger currency, and a boost to domestic demand, was precisely the policy followed by the Japanese in the late-1980s, leading to the biggest financial bubble in living memory and the 20-year hangover that followed.

Furthermore, the demand by the United States, which is backed by the G7 for a renminbi revaluation, is, in our view, a policy of the United States’ default. During the Asian crisis in 1997 to 1998, advanced economies, under the auspices of the IMF, insisted that Asian nations, having borrowed so much, should now tighten their belts. Shouldn’t advance economies be doing the same? In addition, Chinese manufacturing margins are so slim that significant change in exchange rates could wipe them out and force layoffs of millions of Chinese. As it is, labor rates are already climbing in China, further squeezing margins. Lastly, a revaluation of the yuan would only push manufacturing to other cheaper emerging markets, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Bangladesh, and other lower paying nations, without improving the advanced economies trade deficits.

Notwithstanding, some G7 policymakers believe these grumbles are overdone, arguing that the rest of the world should praise the United States and Japan for such monetary policies, suggesting the eurozone should do the same. The war rhetoric implies that the United States and Japan are directly suppressing their currencies to boost exports and suppress imports, which in our view is a zero-sum game, which could degenerate into protectionism and a collapse in trade.

These countries, however, do not believe such currency devaluation strategy will threaten trade. Instead, they believe that as central banks continue to lower their short-term interest rate to near zero, exhausting their conventional monetary methods, they must employ unconventional methods, such as QE, or trying to convince consumers that inflation will rise. Their goal with these actions is to lower real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. If so, inflation should be rising in Japan and in the United States, as shown in Figure 3.9.

As Figure 3.9 also shows, over the past decade, Japan has seen the consumer price index for most periods hover just below the zero-percent inflation line. The notable exceptions were in 2008, when inflation rose to as high as 2 percent, and in late 2009, when prices fell at close to a 2 percent rate. The rise in inflation coincided with a crash in capital spending. The worst period of deflation preceded an upturn. Of course, the figure above does not provide enough data to infer causal effects, but it seems, however, that the relationship between growth and Japan’s mild deflation may be more complicated than the Great Depression-inspired deflationary spiral narrative suggests. The principal goal of this policy was to stimulate domestic spending and investment, but lower real rates usually weaken the currency as well, and that in turn tends to depress imports. Nevertheless if the policy is successful in reviving domestic demand, it will eventually lead to higher imports.

Figure 3.9 Japan’s inflation rate has been climbing since 2010 as a result of economic stimulus

Source: Trading Economics,23 Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

At least that’s how the argument goes. The IMF actually concluded that the United States’ first rounds of QE boosted its trading partners’ output by as much as 0.3 percent. The dollar did weaken, but that became a motivation for Japan’s stepped-up assault on deflation. The combined monetary boost on opposite sides of the Pacific has been a powerful elixir for global investor confidence, if anything, to move hot money onto emerging markets where the interests were much higher than those in advanced economies.

The reality is that most advanced economies have been over-consumed in recent years. It has too many debts. But rather than dealing with those debts—living a life of austerity, accepting a period of relative stagnation—these economies want to shift the burden of adjustment on to its creditors, even when those creditors are relatively poor nations with low per capita incomes. This is true not only for Chinese but also for many other countries in Asia and in other parts of the emerging world. During the Asian crisis in 1997 to 1998, Western nations, under the auspices of the IMF, insisted that Asian nations, having borrowed too much, should now tighten their belts. But the United States doesn’t seem to think it should abide by the same rules. Far better is to use the exchange rate to pass the burden on to someone else than to swallow the bitter pill of austerity.

Meanwhile, European policymakers, fearful that their countries’ exports are caught in this currency war crossfire, have entertained unwise ideas such as directly managing the value of the euro. While the option of generating money out of thin air may not be available to emerging markets, where inflation tends to remain a problem, limited capital controls may be a sensible short-term defense against destabilizing inflows of hot money. Figure 3.10 illustrates how the inflows of hot-money leaving advanced economies in search of better returns on investments in emerging markets have caused these markets to significantly outperform advanced (developed) markets.

Figure 3.10 In 2009, emerging markets significantly outperformed advanced (developed) economies

Source: FTSE All-World Indices.

Currency War May Cause Damage to Global Economy

As more countries try to weaken their currencies for economic gain, there may come a point where the fragile global economic recovery could be derailed and the international financial system is thrown into chaos. That’s why financial representatives from the world’s leading 20 industrial and developing nations spent most of their time during the G20 summit in Moscow in September 2013.

In September 2011, Switzerland took action to arrest the rise of its currency, the Swiss franc, when investors, looking for somewhere safe to store their cash from the debt crisis afflicting the 17-country eurozone, saw in the Swiss franc the traditional instrument to fulfill that role. The Swiss intervention was viewed as an attempt to protect the country’s exporters.

In our view, policymakers are focusing on the wrong issue. Rather than focus on currency manipulation, all sides would be better served to zero in on structural reforms. The effects of such strategy would be far more beneficial in the long run than unilateral U.S., China, or Japan currency action; it would also be much more sustainable. The G-20 should focus on a comprehensive package centered on structural reforms in all countries, both advanced economies and emerging markets. Exchange rates should be an important part of that package, no doubt. For instance, to reduce their current-account deficits, Americans must save more. To continue to simply devalue the dollar will not be sufficient for that purpose. Likewise, China’s current-account surpluses were caused by a broad set of domestic economic distortions, from state-allocated credit to artificially low interest rates. Correcting China’s external imbalances requires eliminating all of these distortions as well.

As long as policymakers continue to focus on currency exchange issues, the volatility in the currency markets will continue to escalate. It actually has become so worrisome that the G7 advanced economies have warned that volatile movements in exchange rates could adversely hit the global economy. Figure 3.11 provides a broad view (rebased at 100 percent on August 1, 2008) of main exchange rates against the dollar.

When it became clear that Shinzo Abe and his agenda of growthat-all-costs would win Japan’s elections, the yen lost more than 10 percent against the dollar and some 15 percent against the euro. In turn, the dollar has also plumbed to its lowest level against the euro in nearly 15 months. These monetary debasement strategies are adversely impacting and angering export-driven countries, such as Brazil, and many of the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS), Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Turkey, and South Africa (CIVETS), and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) blocs. But they also are stirring the pot in Europe. The eurozone has largely sat out this round of monetary stimulus and now finds itself in the invidious position of having a contracting economy and a rising currency.

Figure 3.11 Exchange rates against the dollar

Source: Bloomberg.

These currency moves have shocked BRICS countries as well as other emerging-market economies, including Thailand. The G-20 is clearly divided between the advanced economies—the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, France, Canada, Italy, Germany—and emerging countries such as Russia, China, South Korea, India, Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia, and the like. Top leaders of Russia, South Korea, Germany, Brazil, and China have all expressed their concern over the currency moves, which drive up the value of their currencies and undermine the competitiveness of their exports. If they decide to enter the game, like Venezuela, which has devalued its currency by 32 percent, the world would be plunged into competitive devaluations. At the end of the day, competitive devaluations would lead to run-away inflation or hyperinflation. Nobody will win with these currency wars.

James Rickards, author of Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis, expects the international monetary system to destabilize and collapse. In his views, “there will be so much money-printing by so many central banks that people’s confidence in paper money will wane, and inflation will rise sharply.”24

If policymakers truly want to stage off this currency war, then it is a matter of doing what was done in 1985 with the Plaza Accord.25 This time, however, there will be need for an upgraded version, as this time it will not be only about the United States and the G5, as it was in 1985. It will have to be an Asian Plaza Accord under the support and auspices of the G20. It will have to be about the Asia export led and mercantilist leadership agreeing amongst them. The chances of this happening, of advanced economies seeing the requirement for it, or these economies relinquishing its powers in any measurable fashion, are not at all possible under the current political gamesmanship presently being played.

Currency War Also Means Currency Suicide

Special contribution by Patrick Barron.26

What the media calls a “currency war,” whereby nations engage in competitive currency devaluations in order to increase exports, is really “currency suicide.” National governments persist in the fallacious belief that weakening one’s own currency will improve domestically produced products’ competitiveness in world markets and lead to an export-driven recovery. As it intervenes to give more of its own currency in exchange for the currency of foreign buyers, a country expects that its export industries will benefit with increased sales, which will stimulate the rest of the economy. So we often read that a country is trying to “export its way to prosperity.”

Mainstream economists everywhere believe that this tactic also exports unemployment to its trading partners by showering them with cheap goods and destroying domestic production and jobs. Therefore, they call for their own countries to engage in reciprocal measures. Recently Martin Wolfe in The Financial Times of London and Paul Krugman of The New York Times both accuse their countries’ trading partners of engaging in this “beggar-thy-neighbor” policy and recommend that England and the United States respectively enter this so-called “currency war” with full monetary ammunition to further weaken the pound and the dollar.

I, Patrick, am struck by the similarity of this currency-war argument in favor of monetary inflation to that of the need for reciprocal trade agreements. This argument supposes that trade barriers against foreign goods are a boon to a country’s domestic manufacturers at the expense of foreign manufacturers.

Therefore, reciprocal trade barrier reductions need to be negotiated, otherwise the country that refuses to lower them will benefit. It will increase exports to countries that do lower their trade barriers without accepting an increase in imports that could threaten domestic industries and jobs. This fallacious mercantilist theory never dies because there are always industries and workers who seek special favors from government at the expense of the rest of society. Economists call this “rent seeking.”

Contagion Effect: The Spreading of the Crisis to CIS Member Countries

Since November 2014, the crisis has spread to a number of former Soviet Union countries, especially Belarus, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Moldova. It also affected, to a lesser extent, some countries in CEE. The crisis-contagion mechanisms worked through several channels: decreasing trade and deteriorating terms of trade with Russia, decreasing remittances from migrants working in Russia and, most importantly, the devaluation expectations of households and financial market players. Those former Soviet Union countries, for which Russia is an important trade partner, could not sustain continuation of the nominal appreciation of their currencies in relation to the ruble.

In addition, during the December 2014 phase of the CIS currency crisis, a degree of contagion effect was visible on foreign exchange markets in central Europe, where currencies with flexible exchange rates depreciated against both the dollar and the euro. This affected the Hungarian forint, Serbian dinar, Polish zloty, Romanian leu, and Turkish lira. However, because of the limited trade and financial links between these countries and Russia and Ukraine, investors’ negative reactions to these currencies were rather short-lived.

As discussed in the previous section, among the global factors that contributed to the CIS currency crisis, U.S. monetary policy seems to have played an important role. Since mid-2013, the expectation of the phasing down of QE3, which eventually happened in October 2014, and more recently, expectations of an increase in the U.S. Federal Fund Rate in 2015,27 has led to tighter global liquidity conditions. This could not be fully compensated for by simultaneous monetary policy easing in the euro area and Japan because of the much smaller size of financial markets in euro and yen. As result, net capital inflows into emerging-market economies decreased, growth in the latter decelerated and commodity prices started to fall28 (see Feldstein, 2014, and Frankel, 2014, on the effects of U.S. monetary tightening on oil and commodity prices). During 2014, as depicted in Figure 3.12, especially in the fourth quarter, the dollar appreciated against most currencies with flexible exchange rates.

Figure 3.12 Depreciation against the dollar, in percent, December 2013 to December 2014, selected currencies

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve Board,29 www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g5/current/default.htm

1 In scholarly literature, the abbreviations CEE or CEEC are often used for this concept.

2 The notional barrier separating the former Soviet bloc and the West prior to the decline of communism that followed the political events in eastern Europe in 1989.

3 The Warsaw Pact, formally known as the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation, and Mutual Assistance, and informally as WarPac, was a collective defense treaty among Soviet Union and seven Soviet satellite states in Central and Eastern Europe in existence during the Cold War; Hirsch, Kett, and Trefil (2002, 316). The name applied to the former communist states of eastern Europe, including Yugoslavia and Albania, as well as the countries of the Warsaw Pact; Janzen and Taraschewski (2009, 190).

4 Busky (2000, 9). In a modern sense of the word, communism refers to the ideology of Marxism-Leninism.

5 A former communist country in eastern Europe and northern Asia; established in 1922; included Russia and 14 other Soviet socialist republics (Ukraine and Byelorussia and others); officially dissolved December 31, 1991.

12 The Belavezha Accords is the agreement that declared the Soviet Union effectively dissolved and established the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in its place. It was signed at the state dacha near Viskuli in Belovezhskaya Pushcha on December 8, 1991, by the leaders of three of the four republics-signatories of the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR, including the Russian President Boris Yeltsin, Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk, and Belarusian parliament chairman Stanislav Shushkevich.

13 The Alma-Ata Protocols are the founding declarations and principles of the CIS.

15 A group of countries that have agreed to charge the same import duties as each other and usually to allow free trade between themselves.

16 The Collective Security Treaty Organization, also known as the “Tashkent Pact” or “Tashkent Treaty,” is an intergovernmental military alliance that was signed on May 15, 1992, by six post-Soviet states belonging to the Commonwealth of Independent States, including Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Three other post-Soviet countries, including Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Georgia, also signed the treaty on the following year. Five years later, six of the nine, all but Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Uzbekistan, agreed to renew the treaty for five more years, and in 2002 those six agreed to create the Collective Security Treaty Organization as a military alliance.

17 The “Monroeski Doctrine” was a colloquial description of Boris Yeltsin’s foreign policy strategy in the near abroad. Adapted from the United States’ 19th-century Monroe Doctrine, which prohibited European colonization of the newly independent Latin American republics, the Monroeski Doctrine affirmed the Russian Federation’s position as the dominant power in the entire former Soviet Union. Moscow often invoked the doctrine when it intervened in post-Soviet conflicts in the newly independent states of Eurasia, such as the Tajik Civil War and the separatist conflicts in Nagorno-Karabakh, Transnistria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetiya.

19 The War in Donbass, also known as the War in Ukraine or the War in Eastern Ukraine, is an armed conflict in the Donbass region of Ukraine. From the beginning of March 2014, demonstrations by pro-Russian and anti-government groups took place in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine, together commonly called the “Donbass,” in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution and the Euromaidan movement.

20 Our opinion expressed here is from the point of international trade and currency exchange as far as it affects international trade, and not from the geopolitical and economic aspects of the issue. We approach the issue of currency wars not from the theoretical, or even simulation models undertaken from behind a desk in an office, but from the point of view of practitioners engaged in international business and foreign trade, on the ground, in four different countries.

21 The Economist’s Writers (2013).

22 As of December 2013.

23 www.tradingeconomics.com (accessed December 09, 2013).

25 The Plaza Accord was an agreement between the governments of France, West Germany, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom, to depreciate the U.S. dollar in relation to the Japanese yen and German Deutsche Mark by intervening in currency markets. The five governments signed the accord on September 22, 1985, at the Plaza Hotel in New York City.

26 Patrick Barron is a private consultant in the banking industry. He teaches in the Graduate School of Banking at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and teaches Austrian economics at the University of Iowa, in Iowa City, where he lives with his wife of 40 years. We recommend you to visit his blog at http://patrickbarron.blogspot.com/ or contact him at [email protected].

29 NOK = Norwegian krone; SEK = Swedish krona; JPY = Japanese yen; BRL = Brazilian real; MXN = Mexican peso; EUR = euro; ZAR = South African rand; CHF = Swiss franc; AUD = Australian dollar; CAD = Canadian dollar; MYR = Malaysian ringgit; NZD = New Zealand dollar; GBP = British pound; SGD = Singapore dollar; KRW = South Korean won.