Opening up of China’s capital markets

Abstract:

This chapter reviews the gradual opening up of China’s capital markets, including allowing foreign investors to enter China’s capital markets and allowing Chinese investors to go global. It argues that the unfair competition between SOEs and private firms for listing on China’s stock markets makes many Chinese private firms leave China in search of the financing opportunities of overseas IPOs. Although China’s government tightly controls overseas listing, many Chinese private firms have developed innovative ways, such as the VIE model, for overseas listing. In addition, the chapter discusses the internationalization of Chinese securities firms and developing joint venture securities firms in China.

Introduction

The opening up of Chinese capital markets includes two aspects. One is to allow Chinese companies to join global capital markets; the other is to allow foreign investors to enter China’s capital markets. The opening up is being undertaken in a gradual way, like China’s economic opening up policy. The authority seems more cautious about opening China’s capital markets to foreign investors than about lifting the restrictions to let Chinese investors go outside. In the early 1990s, China faced a great shortage of foreign currencies and thus took very tight control of foreign exchange. To help SOEs solve the shortage of foreign currencies, the authority allowed them to issue RMB-dominated shares to foreign investors; but they were subscribed and traded in US$ and HK$. These were B-shares. In November 1991, Shanghai Vacuum Electron Device Corporation Limited issued RMB 1 million Yuan special RMB-dominated shares at par value of RMB 100 Yuan (US$18.8) per share to overseas investors. This was the first B-share market in China’s stock markets.

Chinese firms’ overseas IPOs

Many Chinese firms want to be listed on overseas capital markets for fundraising because of the difficult and time-consuming procedure for being listed on China’s stock exchanges. The first opening up of China’s capital markets was to allow Chinese firms to be listed on foreign exchanges. Chinese companies have two ways to be listed on foreign exchanges. One is called a direct way; the other is an indirect way. The direct way is with Chinese authorities’ approval for overseas IPOs, and most listed firms have been SOEs. This is often under a model called the Red Chip Model (RCM) for IPO abroad. The indirect way is without government approval, and most of the listed firms have been private firms. One indirect way is called the Variable Interest Entities model (VIE).

The first wave of Chinese firms going global was from 1993 to 1997. Many large Chinese SOEs took their first steps into the global capital markets during the period. The first Chinese firm to be listed on overseas markets was Tsingtao Brewery Corporation Limited. It was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in June 1993. This was the first H-share. In August 1994, Shandong Huaneng Power Development Corporation Limited became the first Chinese firm to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange. This was the first N-share. In March 1997, Beijing Datang Power Generation Corporation Limited became the first L-share to be listed on the London Stock Exchange. In May 1997, Tianjin Zhongxin Pharmaceutical Group became the first S-share to be listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange. Although their fundraising was not a large amount (Figure 9.1), those overseas IPOs provide Chinese firms with more options in corporate financing. Further, it drives the globalization of Chinese firms. Since then, more and more Chinese firms have looked for overseas IPOs. But the Asian crisis in 1997 made Chinese firms slow down their pace of going global.

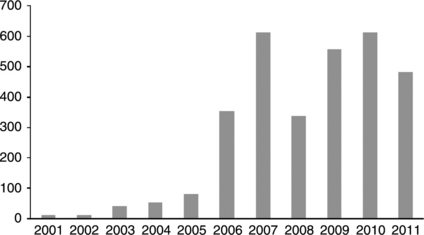

The second wave of Chinese firms’ listing on global capital markets was from 2002 to 2007. China’s entry into the WTO in 2001 triggered another round of Chinese firms’ passion for being listed on overseas capital markets (Figure 9.2). According to CSRC, from 2002 to 2007, Chinese overseas IPOs increased from 32 to 103. The fundraising reached the historic value of RMB 314.88 billion Yuan. The American financial crisis emerging from Wall Street in 2007 slowed the pace of Chinese firms again. So, in 2008, Chinese overseas IPOs declined to a very low level (Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 Annual fundraising of Chinese firms from overseas markets from 2002 to 2011 (RMB billion Yuan) Source: CSRC

In 2011, 386 Chinese companies realized IPOs with the total financing value of about RMB 409.7 billion Yuan, 42.5 percent less than in 2010. Among them, 14 Chinese companies were listed on American capital markets, and 62 were listed on HKEX. The IPOs in Hong Kong financed RMB 111.72 billion Yuan (HK$136.53 billion). Hong Kong became the largest overseas financing market for Chinese companies (Table 9.1). In that year, Chow Tai Fook was the largest IPO case in overseas markets, with the financing value of HK$15.75 billion.

During the 10 years from 2002 to 2011, there were 5 years in which Chinese firms raised more funds from HK than the domestic capital market. For example, in 2006, Chinese firms raised nearly RMB 300 billion Yuan from HK capital markets, while the fundraising from mainland capital markets was less than half of the fundraising from HK. In 2011, 62 Chinese firms were listed on HKEX and raised funds of RMB 111.72 billion Yuan (HK$ 136.53 billion), accounting for about 27.3 percent of the Chinese firms’ global fundraising, including China. HKEX was the second-largest fundraising market after SZSE (Figure 9.4).

If we look at IPO performance in different markets, it can be seen that SSE had the best fundraising performance. The average fundraising for each IPO reached RMB 2.67 billion Yuan. The average fundraising of each IPO in HKEX was about RMB 1.8 billion Yuan, the second-best fundraising performance (Table 9.2). The American stock market is becoming less attractive to Chinese firms. NYSE and NASDAQ accounted for only 2.1 percent and 0.9 percent, respectively, of the total fundraising.

Red Chip Model for overseas IPO

Chinese firms normally have two ways of being listed on overseas capital markets. One is called the Red Chip Model (RCM). In this mode, the IPO listing entity is an offshore vehicle company. A domestic firm establishes offshore companies or overseas shell companies (special purpose vehicles, or SPVs), which are normally located in tax havens. The domestic firm then injects its equities and business into one of the SPVs. That is, the SPV acquires the domestic firm’s equities. Then the SPV is listed in overseas stock exchanges. The RCM has two types, big RCM and small RCM. Big RCM is often used by SOEs for overseas listing. In 1997, the State Council issued Notice of the State Council on Further Strengthening Management of Issuance and Listing of Shares Overseas (20 June 1997 G.F. [1997] No. 21) and provided guidance for the approval path for SOEs being listed abroad. Many large SOEs, such as COFOC, China Unicom, China Agri-Industries and China Minmetals, realized overseas IPOs in this way. IPO abroad for Chinese firms should be approved by the Chinese government. SOEs normally do not have many difficulties in obtaining approval.

Small RCM was usually used by private firms for their overseas IPOs before September 2006. It is similar to big RCM. In this model, a domestic firm establishes offshore companies. One of the offshore companies acquires the equities of the domestic company. Then, the offshore company is listed on overseas stock exchanges. But acquisition of domestic assets by SPV, by either cash deal or share swap, needs the approval of MOFCOM, and the domestic firm’s IPO abroad needs the approval of CSRC. Some famous private Chinese companies, such as Mengniu and Baidu, realized overseas IPOs by this model. However, on 8 August 2006, MOFCOM, SASAC, SAT, SAIC, CSRC, and SAFE jointly issued the Regulations Regarding the Acquisition of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors (2006 No. 10). It was effective from 8 September 2006. Since the release of the famous No. 10 document, there has been no overseas IPO under small RCM due to the difficulty of obtaining approval.

VIE model for overseas IPO

Since the No.10 document came into effect, those firms, such as private firms, that still want to be listed in overseas capital markets cannot take small RCM any more. They have developed some indirect ways to realize IPO abroad. One famous and popular way is the VIE model. The VIE model is also called the SINA-model structure, since it was first used by a Chinese internet firm, SINA, a famous dot.com company, for its 2000 listing on NASDAQ. In the small RCM, it is critical for the offshore company to acquire the domestic firm. Since a direct acquisition cannot be approved by Chinese authorities, some firms figure out an indirect way. They change the acquisition to a contractual arrangement by which the offshore company controls the domestic firm’s operation and management. The profits of the domestic company would also flow to the offshore company and then ultimately be consolidated by the offshore company for IPOs abroad.

Another reason for using the VIE model is because of China’s restrictions on some industries to foreign investors. Sina used the VIE as a way to avoid restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI) in the value-added telecom services sector. Many investors, both foreign and Chinese, use the VIE model in the sectors where FDI is either restricted or prohibited. In China, not all industries are open to foreign investors. According to the Provisions on Guiding the Orientation of Foreign Investment, promulgated in 2002, and the Foreign Investment Industrial Guidance Catalogue, revised in 2007, industries are classified into four categories: encouraged, permitted, restricted and prohibited. For restricted industries, foreign investors face higher qualifications or stricter requirements. Foreign investors are not permitted to invest in prohibited industries at all. So, VIE becomes a way to avoid the restrictions. In addition, for those domestic companies in restrictive industries without many physical assets (such as internet or telecommunications), the VIE model can also be used to obtain financing from overseas markets through overseas listings. By April 2011, 42 percent of Chinese IPOs abroad had used the VIE model.

Although the Chinese authority has no clear prohibition against the VIE model in China, there has been no express endorsement of the VIE model either. It is a grey area in the Chinese legal system. It allows both domestic and foreign investors to circumvent government reviews and regulations, but this also means that it is not backed up by the authority. So, the VIE model possesses potential legal risks. In 2012, the VIE model has attracted the attention of CSRC, which is planning to bring the model under its supervision.

Delisting from American stock markets

Since 2011, due to short-selling China in American capital markets by American short-selling financial institutes, such as Muddy Waters and Citron Research, some Chinese firms listed on American stock markets have started to go private, which has become a trend. In the past 2 years, more than 50 Chinese firms have delisted from American stock markets. In 2012, at least 18 listed companies had delisted from NYSE or NASDAQ (Table 9.3). Focus Media Holding Limited (NASDAQ: FMCN), which operates China’s largest lifestyle-targeted interactive digital media network, is also going private and is expected to be delisted in 2013. Focus Media raised more than US$170 million through its IPO in July 2005, which was at that time the largest NASDAQ listing by a Chinese company. The share price reached the peak above US$66 in November 2007. But the stock plunged 40 per cent in a single day in November 2011, when Muddy Waters short-sold it. It will be the largest delisting case for Chinese companies in American stock markets.

Table 9.3

Chinese companies delisting from American stock markets in 2012

| Chinese company | Delisting from | Delisting date |

| SCEI Sino Clean Energy | NASDAQ | 25 September 2012 |

| CVVT China Valves Technology | NASDAQ | 21 September 2012 |

| BEST Shiner International | NASDAQ | 7 September 2012 |

| CDII China Direct Industries | NASDAQ | 11 July 2012 |

| CAST ChinaCast Education | NASDAQ | 25 June 2012 |

| CNEP China North East Petroleum | NASDAQ | 21 June 2012 |

| XINGF Qiao Xing Universal Resources | NASDAQ | 15 June 2012 |

| WUHN Wuhan General Group | NASDAQ | 15 June 2012 |

| QXMCF Qiao Xing Mobile Communication | NASDAQ | 15 June 2012 |

| CNGL China Nutrifruit | NYSE Amex | 15 June 2012 |

| AOBI American Oriental Bioengineering | NYSE Amex | 29 May 2012 |

| CKUN China Shenghuo Pharmaceutical- | NYSE Amex | 10 May 2012 |

| UTRA Universal Travel Group | NYSE | 8 May 2012 |

| ZSTN ZST Digital Networks | NASDAQ | 26 April 2012 |

| CHNG China Natural Gas | NASDAQ | 8 March 2012 |

| CSKI China Sky One Medical | NASDAQ | 8 March 2012 |

| FEED Agfeed Industries | NASDAQ | 10 February 2012 |

| DGWIY Duoyuan Global Water | NYSE | 26 January 2012 |

Chinese high-tech companies liked to be listed on the tech-heavy NASDAQ, not only because of low IPO cost but also because they thought their stock would be actively traded and highly rated by Western investors. However, American investors always look at things from a very American perspective and do not well understand the values of Chinese listed companies, which left their share prices undervalued. The main reasons for Chinese firms’ delisting include short-selling by American financial companies, low fundraising and high cost to maintain being listed in American stock markets. Chinese firms feel that they were always undervalued by American investors, while the high P/E ratio and considerable amounts of fundraising on the mainland are attracting more and more Chinese firms that were listed on overseas capital markets to go back home. Since the firms’ businesses are on the mainland, they are well known to domestic investors. Thus, they can make more fundraising than in overseas markets. Another reason is that Sino-US economic and political conflicts sometimes put the listed firms in a very unfavorable situation.

QFII

The Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) program was launched in 2002 to allow licensed onshore foreign investors to trade Yuan-dominated A-shares in China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. The total quotas of QFII were US$20 billion by the end of 2011. In December 2002, China launched the QFII program to allow licensed foreign institutional investors to trade A-shares on the secondary market. But the authority took total control of the quota. UBS Warburg became the first financial service firm to get a qualified foreign institutional investor license. With CSRC approval, the licensed foreign institution then needs to apply to SAFE (State Administration of Foreign Exchange) for a foreign exchange quota used for securities investment, which ranges from US$50 million to US$800 million. That was because China still exercises foreign exchange control. Meanwhile, some domestic and foreign banks had been approved as QFII custodian banks for QFIIs’ custodian services, where special RMB accounts are opened to enable domestic trading. By the end of November 2012, 199 foreign investors had qualified as QFIIs, including about 100 asset management companies, 50 investment banks, 15 sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) and ten each for pension funds, insurance companies, university fund and donation funds respectively. By early December 2012, there were 201 QFII institutions in total.

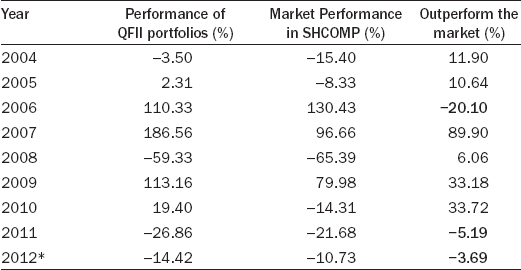

QFII has a quota control. In 2002 when QFII was first launched, the total quota was $10 billion. In 2007, it was raised to $30 billion. In April 2012, it was increased to $80 billion. Meanwhile, for each licensed foreign institution, there is a quota limitation. By the end of November 2012, each QFII’s quota should not be more than $1 billion. It was $800 million for each QFII. It can be seen that China is opening its capital markets in a gradual way, under control. From the investments, it can be seen that QFIIs tend to like investing blue chip stocks in the A-share market. QFII investments performed more poorly than the market for only 3 of the past 9 years. In most years, QFII outperformed the A-share market. In 2007, they even outperformed the market by 89.90 percent. However, due to small investment size and quota control, QFII has only limited influence on China’s stock market (Table 9.4).

QDII

In May 2006, the Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor (QDII) program was launched, which allows licensed domestic investors to invest in overseas markets. By the end of October 2011, there were 105 QDIIs with an approved quota of $86.297 billion, more than the QFII quota of $80 billion. Since China had the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves, more than $3.2 trillion by November 2012, China’s authority is increasing the QDII quotas to encourage Chinese investors to go global. About 50 percent of China private funds involve overseas investment. About 40 percent of sunshine private funds have taken outbound investments. Another 30 percent of sunshine private funds are planning on going global. Most private funds register in the Cayman Islands. A famous Chinese private fund is Pureheart Asset Management Corporation Limited. Due to the global crisis and appreciation of the RMB, QDII has been difficult. Most QDIIs lost money from 2007 to 2011. In 2010 no QDII funds were issued. Since 2012, the performance of QDIIs is improving. By 29 November 2012, the average return for the 51 QDII funds reached 6.34 percent. The top three QDII funds’ returns are over 15 percent.

RQFII

A further opening up of China’s capital markets is the offshore RMB Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFII) program. The RQFII program, launched on 17 August 2011, is a scheme for offshore RMB funds to return to China’s domestic stock markets through local securities firms or fund firms. It allows qualified securities firms to invest in mainland securities. The initial quota was RMB 20 billion Yuan, and nine offshore funds had been granted RQFII licenses. No more than 20 percent of quota could be invested in China’s stock A-share markets, and no less than 80 percent in China’s bond markets. The purpose of launching RQFII is to drive the internationalization of the RMB and import capital to China’s capital markets. RQFII supports Hong Kong as an RMB offshore center. The initial investment quota for RQFII was set at 20 billion Yuan ($3.1 billion). Allowing offshore Yuan funds to invest in mainland securities will encourage more local financial institutions to bundle the Yuan funds to develop more Yuan-denominated financial products in the city. By 8 December 2011, the total RMB in Hong Kong reached RMB 625 billion Yuan, of which RQFII accounted for 3.2 percent. By the end of 2012, Hong Kong had RMB of about 700 billion Yuan. Due to strong demand, in April 2012, the quota was increased by RMB 50 billion, and in November 2012 by RMB 200 billion. So, by the middle of December 2012, the total quota of RQFII reached RMB 270 billion Yuan.

But the opening up is still limited. So far, only Hong Kong branches of domestic fund firms and securities firms can obtain RQFII qualification. Investment opportunities for foreign institutions are restricted. In particular, RQFII funds are required to invest no less than 80 percent of the granted quota in fixed-income products, which means the percentage allowed for equity investment cannot exceed 20 percent of the fund portfolio. Moreover, a transparent approval system for QFII and RQFII applicants has been lacking. In many cases, rules of approval are not clear and reasons for denial are not publicly disclosed. Regulators, including CSRC and SAFE, have not disclosed a specific time frame regarding the complete QFII and RQFII quota approval process for foreign investors to navigate.

Joint venture securities in mainland China

Another aspect of opening up China’s capital market is allowing foreign financial institutions to establish joint venture (JV) securities firms with Chinese securities firms in mainland China. Wholly foreign-owned securities firms have not been allowed, as with other financial institutions. The first JV securities firm was CICC, a cooperation between CCB and Morgan Stanley, established in 1995. After China’s accession to the WTO, more JV securities firms were established. The first one was a Sino-French JV established in 2003, China Euro Securities. It is currently Fortune CLSA Securities. Other JV securities include BNP Paribas China, which was established by Chinese Changjiang Securities and French BNP, and Daiwa SSC Securities, which is a JV between Shanghai Securities and Japanese Daiwa Securities Capital Markets. In 2004, Goldman Sachs and Chinese Gaohua Securities established Goldman Sachs Gaohua Securities. In 2008, Credit Suisse Founder Securities Limited (CSFS), which is a JV between Founder Securities and Credit Suisse, was established. In 2008, Shanxi Securities and German Deutsche Bank established Zhongde Securities. Benefiting from the US and China Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED), CSRC opened China’s capital market further. In 2011, three JV securities were established: Morgan Stanley Hunxin Securities, established by Hunxin Securities and Morgan Stanley; Huaying Securities, which is a JV between Chinese Guolian Securities and Royal Bank of Scotland Group (RBS); and J.P. Morgan First Capital Securities, established by Chinese First Capital and J.P. Morgan. In 2012, Citi Orient Securities, which is a JV between Citigroup Global Markets Asia Ltd and Orient Securities Company, was established. UBS AG established UBS Securities with five Chinese partners. According to SAC, there are 11 joint venture securities firms on the mainland. On 11 October 2012, CSRC issued the Revised Rules for Establishment of Securities Companies with Foreign Equities Participation. By the new regulation, foreign investors can hold stakes as high as 49 percent in JV securities firms. Before that, JV securities firms had an investment cap of a third of those companies’ equities. Meanwhile, the JV can apply for permission from CSRC to expand their businesses 2 years after going into operation in China rather than the previous 5 years.

Most JV securities firms in China are not performing as expected. Only about half of them make a profit. The main problem for the JV securities firms is not the stakes of the joint venture, but the license, which limits their business development. JV securities mainly focus on investment banking and cannot carry out brokerage business. Only a few securities firms, such as Morgan Stanley, have a full license. Meanwhile, the cooperation between two partners of the JV often faces culture conflicts and management problems. The future of JV securities firms in the mainland may depend on developing derivatives-related business and innovative business, because the two businesses are often strengths of foreign partners of JV securities firms.

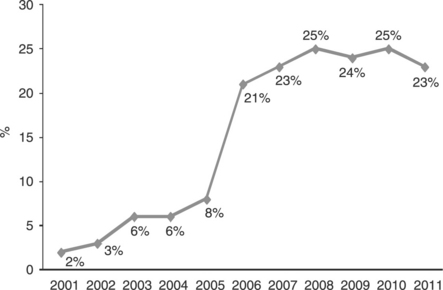

Internationalization of Chinese securities

The internationalization of Chinese securities firms is still in its infant stage. Their business is mainly in investment banking, and the market is focused on Hong Kong. About 20 Chinese securities firms have established branches in Hong Kong. Their business focuses on mainland firms’ IPOs in Hong Kong, particularly on H-share-related business. On 15 July 2003, a mainland firm, Tsingtao Beer, was listed on HKEX and became the first H-share. Since then, many Chinese firms, particularly SOEs, have been listed on HKEX. From 2001 to 2011, the total market value of H-shares increased from about $11 billion to $482 billion (Figure 9.5). Their market value accounted for about 2 percent of the total market value of HKEX in 2001. It increased to 23 percent in 2011 (Figure 9.6). During this period, Chinese securities firms were internationalized. From 2001 to 2011, among 491 IPOs on the Hong Kong stock market, 189 of them were taken by mainland securities firms to be main underwriters. From 1993 to 2011, there had been 22 H-share IPOs with fundraising of more than $2 billion. Chinese securities firms involved 20 of them as underwriters. On 27 October 2006, ICBC, one of China’s Big Four banks, realized “A + H” IPOs, listed on both the domestic A-share market and the Hong Kong stock market on the same day. The total fundraising reached $22 billion, which was the largest for both stock markets. It was CICC that served as underwriter for the IPOs. From 2006 to 2011, there were nine “A + H” IPOs. They were all served by Chinese securities firms as underwriters. In particularly, CICC was involved with seven of them. In 2011, 13 mainland securities firms were involved with mainland firms’ IPOs in Hong Kong, compared with only six in 2001. In 2011, the market share of Chinese securities firms in Hong Kong was 12.5 percent in IPO and 18.9 percent in refinancing business. In particular, CICC and CITIC Securities finished underwriting business of $184 million in Hong Kong, accounting for 1.32 percent of HK market shares.

Figure 9.6 Market shares of H-share in total market value of HKEX from 2001 to 2011 Source: Bloomberg

In the next few years, the internationalization of Chinese securities firms may enter the second stage, which involves more M&A business. Some Chinese securities firms are exploring international markets in that field. In 2011, CITIC PE Advisors, which is the direct investment fund of CITIC Securities, supported SANY Heavy Industry, China’s largest construction equipment group, to acquire Putzmeister, a large German engineering group. But securities firms’ profits and revenues from international markets are still quite small. In 2010, the overseas profit of Chinese securities firms was only about 3 percent of their total profits. In 2011, Haitong Securities, which was one of the best performing Chinese securities firms in international markets, had overseas revenue of only $809 million, or 8.7 percent of its total corporate revenue. Chinese securities firms are at the beginning of going global.

Lang and Sun (2012) point out that the openness of China’s A-share market and bond market is only 0.8 percent, which is the lowest among emerging economies. The stock markets of other emerging economies have openness of 26 percent on average, and 13 percent for bond markets. The gap in opening up between China and other emerging economies is huge. One reason may be because China’s government is taking a gradual approach to opening China’s capital markets. For example, with the approval of both the State Council and CSRC, Chinese financial companies can undertake transactions in overseas futures markets for the purposes of hedging. But the products they trade have to be approved by MOFCOM. There has been a worldwide trend to open up capital markets and encourage financial firms to go global. But Chinese firms are still quite weak in their competitiveness and international experience. In the banking field, domestic banks pay more attention to the innovation of financial products and services than to innovative internal mechanisms. China needs a strategy to open its capital market. Besides, in opening up China’s capital markets, China’s private firms, which are always at a disadvantage compared with SOEs in financial markets, should not be forgotten. When foreign investors ask for national treatment, Chinese private firms and investors should be borne in mind. The opening up of Chinese capital markets has two meanings: one is to open up the capital markets to domestic firms, particularly private firms; the other is to open them up to the world and foreign investors.

Summary

An efficient and developed capital market needs to be an opened market. As with China’s economic reform, China’s capital markets are being opened with a gradual strategy and under government planning and control. The openness follows the roadmap: China first opened the markets to foreign investors and let them enter China’s capital markets, and then allowed Chinese investors to go outside to invest. Chinese investors, investment banks and financial institutions are going global. They normally use Hong Kong as a bridge, through which they go global and also learn experience of going global. They establish offices and branches in Hong Kong. Hong Kong has been the largest and most important market for Chinese firms going global.

When discussing the opening up of China’s capital markets, a simple question should be asked first: What is the purpose of opening up? If it is to cause a so-called Catfish Effect or Weever Effect that allows foreign investors to enter China’s capital markets, and by this to improve the efficiency of these markets, foreign investors should have some strength to influence them. However, given quite a small quota compared with the total market value, QFIIs’ influence has been quite limited. Meanwhile, China’s stock exchanges have not so far offered foreign companies an opportunity to raise capital. In addition, the capital markets are strictly regulated. There are requirements and approvals for foreign investments in China’s capital markets and Chinese investments abroad. The opening up of China’s capital markets is still at the beginning stage.

For Chinese financial firms, including securities firms, due to cultural conflicts and shortage of financial professionals for global markets, their performance in going global is still modest. How to overcome cultural differences and develop an appropriate management model and strategy to compete in global capital markets has been a common problem for most Chinese financial firms. Besides, opening up also has another meaning, which is to open the capital markets to China’s private firms and investors. It seems that the authorities are focusing on opening up China’s capital markets to foreign investors and allowing Chinese investors to go global, while ignoring the opening up of China’s capital markets to Chinese private firms.