China’s stock market

Abstract:

This chapter tries to answer two questions: what does China’s stock market look like, and why is it here? It introduces the structure of China’s stock market. The evolution paths and latest performances of the markets are described. The relationship between China’s economic growth and its stock market development is analyzed. The chapter also tries to explain why China’s stock market performs poorly and why China’s sustainable economic growth is not reflected in its stock market performance. It is argued that China’s stock market is distorted and has more of a financing function than an investment function. Furthermore, the problems and challenges of developing China’s stock market are discussed. The chapter also discusses the expected International Board and some problems caused by launching the board.

Introduction

China’s stock market was officially started from 1990, when Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) and Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) were in operation. As a part of China’s economy, China’s stock market is developed with government planning and guidance. The original purpose in developing the stock markets was to provide state-owned enterprises (SOEs) with a new financing channel besides bank loans. China is trying to establish a multi-layered capital market system to finance different types of enterprises. It mainly includes the A-share market, the B-share market, the Growth Enterprise Market (GEM), the Small and Medium-sized Enterprise Board (SMEB) and The Third Board Market (TBM). The A-share market, which dominates China’s stock market, mainly serves SOEs, as does the B-share market. GEM, TBM and SMEB mainly finance private firms, including micro-enterprises and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). China’s A-share market is often called the main board, and has been the second-largest in the world, after the New York Stock Exchange, by its market value and trading volume. By the end of 2011, there were 2342 listed companies in SZSE and SSE. Their total market value was about Renminbi (RMB) 21.48 trillion Yuan. Tradable shares’ market value was RMB 16.49 trillion Yuan. In 2011, China’s A-share market realized fundraising of RMB 507.3 billion Yuan. The stock value traded was RMB 42.16 trillion Yuan. In the A-share market, there were 165.469 million stock investment accounts, and 140.5037 million of them were valid. Individual investors accounted for 99.6 percent. In 2011, more than 85 percent of the accounts lost money. By the end of 2012, the total listed companies on China’s stock markets reached 2494. As the most important part of China’s capital markets, China’s stock market has greatly financed China’s economic growth.

For the past 20 years, the fluctuations of China’s stock market have been among the most dramatic in the world. On 6 June 2005, China’s stock market saw its historical bottom. The Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index (SHCOMP) closed at 998.22. About two years later, on 16 October 2007, SHCOMP reached the historically high 6124.04. Since then, the stock market has tended to decline. In 2010, SHCOMP closed at 2808, decreased by 14.31 percent for the year. However, the total capital raised by the stock market for the year reached RMB 1 trillion Yuan, the highest in the world. The total initial public offerings (IPOs) were 349, also the highest in the world. Those IPOs raised capital for RMB 492.131 billion Yuan. Capital raised from seasoned equity offerings and allotment of shares reached RMB 365.68 billion Yuan and RMB 143.82 billion Yuan respectively. Meanwhile, about 70 percent of stock investors lost money in 2010. In 2011, the stock market performed even more poorly. At the end of 2011, SHCOMP closed at 2199.42, decreased by 21.68 percent for the whole year. SZCOMP closed at 8918.82, decreased by 28.41 percent for the year. Shenzhen SME Price Index closed at 4295.87, decreased by 37.09 percent. Shenzhen ChiNext (China’s National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (NASDAQ)) Price Index closed at 725.90, decreased by 35.88 percent for the year. For 2011, the total trading volume decreased by 22.72 percent. The daily trading value was RMB 172.807 billion Yuan, decreased by 23.36 percent from 2010. But the total capital raised from the stock market was RMB 864.8 billion Yuan, the highest in the world.

In the B-share market, share trading has been so inactive that it has lost its fundraising function. B-share listed companies are considering their options, such as delisting from the B-share market or transferring to the A-share market. The future of the B-share market is being discussed and may be solved in the next two or three years. The New Third Board, an over-the-counter (OTC) trading system, is expanding from a regional system to a nationwide trading market. It is emerging as an important platform for directly financing the growth of small private firms. It is expected to be China’s NASDAQ. China’s GEM has been in a period of adjustment after several years’ fast growth with very high price to earnings (P/E) ratios and IPO prices. A department at the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has been established specially to supervise GEM. China’s stock market is developing under China’s emerging and transitional economy. Thus, it also has some characteristics of both an emerging and a transitional economy, such as lack of market mechanisms and frequent administrative interferences, which often prevent it from being an efficient capital market.

In 2011, China’s stock market performed the best in financing in the world. From 2009 to 2011, China’s main board had been global champion of IPO fundraising for three consecutive years. The A-share market provided financing of more than RMB 500 billion Yuan. Seasoned equity offering became the most important way of fundraising and raised more capital than IPO in the year. One hundred and eighty-six listed companies took seasoned equity offerings for fundraising of RMB 387.4 billion Yuan, accounting for 55 percent of total stock fundraising (Figure 1.1). The largest seasoned equity offering was Hebei Steel, which raised RMB 16 billion Yuan. Fifteen listed companies took allotment of shares and raised capital for RMB 41.6 billion Yuan, accounting for 6 percent of total stock fundraising. There were 277 IPOs of 19 industries in China’s stock market and the capital raised was RMB 272 billion Yuan, accounting for 39 percent of the fundraising of the year. Most of the listed companies were from Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Guangdong Provinces and Beijing. The average P/E ratios of those IPOs were as high as 46. It was found that both IPO prices and P/E ratios for the whole year were highest in the first quarter and were lowest in the second quarter. Most of those IPO prices were between RMB 11 and 30 Yuan (Figure 1.2). About 50 percent of IPO prices were between RMB 30 and 50 Yuan. GEM often means high IPO price and P/E ratios. Its IPO prices were normally higher than those of the main board. GEM had 17 IPOs whose IPO prices were over RMB 40 Yuan, while the main board had just three and SMEB had ten whose IPO prices were over RMB 40 Yuan. Ledman Optoelectronic (300162: SZSE), which specialized in high quality LED products, had the highest P/E ratio of 131 listing in GEM. The lowest one, Tongkun Group (Stock 601233: SSE), had the P/E ratio of only 12.22 listing in SSE.

Figure 1.1 Different types of fundraising in China’s stock market in 2011 Source: SZSE (www.szse.cn) and SSE (www.sse.com.cn)

Figure 1.2 IPO price distribution of different stock markets in 2011 (RMB Yuan) Source: SZSE (www.szse.cn) and SSE (www.sse.com.cn)

High IPO prices often indicate the stocks are overvalued and overpriced, which normally cause poor performance when the stocks are floated on markets. It has been a frequent phenomenon in China’s stock markets that, on the first trading day of a stock, its price always falls below its IPO price. In 2011, 39.5 percent of IPOs on the main board saw a fall on their first day’s trading (Figure 1.3). That falling was still as high as 32 percent in 2012. Of the listed companies on GEM, 23.4 percent saw their prices fall on the first day’s trading in 2011, and 23 percent in 2012. In the primary market, fund companies and securities firms are the main investors. Securities firms use the stock primary market for their collective wealth management products. According to the Securities Association of China (SAC), there were 2878 institutions involved in primary markets for new stock placements in 2011. Among them, fund companies were the most active. They involved IPO placements for 2240 times and seasoned equity offerings for 101 times. The total capital those fund companies invested was about RMB 215.55 billion Yuan. In 2011, 77 securities firms were involved in the investment banking business, nine more than in 2010. The top five securities firms had about 27 percent market share (Table 1.1). The concentration ratio was lower than in 2010.

Table 1.1

Market shares of the top five securities firms in 2011

Source: Securities Association of China (http://www.sac.net.cn)

Figure 1.3 The percentage of listed companies whose prices fell below their IPO prices on the first day’s trading Source: SZSE (www.szse.cn) and SSE (www.sse.com.cn)

China’s A-share market

The A-share market is the most important part of China’s stock market. It is dominated by SOEs, particularly large SOEs, and provides them with financing support. On 1 December 1990, SZSE started a trial operation. On 11 April 1991, its operation was officially approved by the central bank, People’s Bank of China (PBOC). In fact, it was named Shenzhen Securities Market at first rather than Shenzhen Stock Exchange. The main reason was that it was much easier to approve a market being opened than a stock exchange. At that time, there was an argument over whether a stock exchange could be launched, since a stock exchange was regarded as capitalism and it might have been a political risk to launch it. Several years later, Shenzhen Securities Market changed its name to Shenzhen Stock Exchange. On 19 December 1990, SSE officially came into operation. So, SSE was the first stock exchange officially, while SZSE was the first stock exchange in operation. They were both locally managed stock exchanges. SSE was under the Shanghai government, while SZSE was under the Shenzhen government. Since then, China’s A-share market, made up of SZSE and SSE, has been developed. Since 1990, the A-share market has experienced dramatic changes. Its development can be basically divided into two stages. The first stage was from 1990 to 2004. During that period, non-tradable shares dominated the stock markets, and tradable shares accounted for only about one-third of the total outstanding. The A-share market was not as liquid as it should be. It was a skewed stock market. The second stage was from 2005. The non-tradable share reform took place and achieved success. The A-share market has achieved better liquidity.

China’s stock market has developed fast over the past ten years. In 2001, the total of listed companies was 1160. But by the end of 2012 it was 2494. In 2001, its market value was only RMB 4.633 trillion Yuan, while in 2011 the market value reached RMB 21.48 trillion Yuan. More important, the tradable shares’ value increased from RMB 1.34 trillion Yuan to RMB 16.49 trillion Yuan. From 2001 to 2011, the traded share volume and traded value increased by 13.62 times and 12.59 times respectively. The traded volume surged from 246.734 billion shares to 3.36 trillion shares. The traded share value climbed from RMB 3.327 trillion Yuan to RMB 41.877 trillion Yuan respectively. Looking at industries of listed companies, in 2001 about 50 percent of stock market value went to manufacturing. The mining industry contributed 8 percent of market value (Table 1.2). But in 2011 manufacturing only accounted for 33 percent of market value, while finance and insurance accounted for 29 percent. It should be noted that, among all industries, banking had been the largest fundraiser in China’s stock markets. In 2001, the fundraising of banking accounted for 67 percent of the total stock markets, while in 2011 it was still the largest, accounting for 43 percent.

From an investor’s perspective, the A-share market is dominated by a large number of individual investors. According to China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation Limited (CSDCC), by the end of October 2012 the small investors, whose investment in the A-share market was less than RMB 10,000 Yuan, accounted for 38.86 percent of the total stock investors. Those with investment of less than RMB 100,000 Yuan accounted for 86.43 percent. The poor performance of the A-share market has forced many investors to close their accounts and leave the A-share market. In the first half of 2012, about 222,200 investors closed their accounts in the A-share market. At the end of November 2012, accounts of the A-share market still in trading operation were only 3.8 percent of total accounts, the lowest since 2008 when the statistical work was undertaken.

The performance of China’s A-share market

The A-share market has two exchanges, SZSE and SSE. SSE is much larger than SZSE in market value of trading stocks. In 2011, the total stocks’ market value on SZSE was only about half that of SSE. In 2012, China’s A-share market performed among the worst of the global stock markets. For the whole year, SHCOMP only surged by 3.17 percent, and SZCOMP was only up 2.22 percent. Both of them were much lower than China’s annual interest rates of 3.25 percent in 2012. The poor performance caused stocks trading to decrease. According to SSE and SZSE, the trading values of stocks, funds and warrants were RMB 42.16 trillion Yuan, RMB 640 billion Yuan and RMB 347.4 billion Yuan in 2012, decreased by 22.72 percent, 29.24 percent and 76.82 percent, respectively, from 2010. But the trading value of bonds on exchanges reached RMB 20.66 trillion Yuan, increased by 203.56 percent. Bond issuing on exchanges contributed to fundraising of RMB 507.3 billion Yuan. Due to the poor performance of the stock market for the past several years, listed companies prefer bond issuance for financing. In 2011, nine listed companies issued convertible bonds and raised RMB 41.32 billion Yuan. That was RMB 4.591 billion Yuan for each company on average. Eighty-three listed companies issued corporate bonds and raised RMB 129.12 billion Yuan, or RMB 1.556 billion Yuan each on average. Enterprise bonds were issued for RMB 355.394 billion Yuan.

The fast growth of China’s stock market brings a great opportunity for investment banking. In 2011, 64 securities firms were involved in underwriting business. CITIC Securities completed underwriting business worth RMB 71.185 billion Yuan and was ranked in first position (Table 1.3). PingAn Securities completed 42 underwriting deals and came top in deal quantity (Table 1.4).

Table 1.3

The top five underwriters’ underwriting business value in 2011 (RMB billion Yuan)

Source : SAC (www.sac.net.cn)

According to SAC, by the end of 2011 there were 109 securities firms, three more than in 2010. Their operation outlets reached 5032, increased by 404 from 2010. The total assets were RMB 1.57 trillion Yuan, decreased by 20.3 percent from 2010 (Table 1.5). The average assets for each securities firm were about RMB 14.4 billion Yuan. Their total net assets were RMB 630.3 billion Yuan, increased by 11.28 percent. The average net asset for each firm was RMB 5.78 billion Yuan. The revenues of securities firms come mainly from brokerage business. In 2011, brokerage business contributed 51 percent of securities firms’ revenue. Their average commission rate was 0.081 percent, decreased by 15.25 percent. Investment banking contributed 18 percent of the total revenue. The securities firms had 261,802 registered employees, including 1958 analysts, 18,231 investment consultants and 37,456 brokers. Among the securities firms, 88 had research departments, which published 162,357 research reports in 2011, 23 percent more than in 2010. The research departments had 4347 employees in total. Asset management business is becoming popular among the securities firms. In 2011, there were 60 securities firms developing asset management business. They developed 284 products, of which 275 were approved. The total asset value managed was RMB 128.265 billion Yuan. But the performance of asset management products was disappointing. Of the 275 products, only 47 achieved a positive return, accounting for 17.1 percent; 7 of them had a return of zero, accounting for 2.5 percent; all others lost money, accounting for 80.4 percent (Figure 1.4). The main reason was the poor performance of China’s stock markets. Of the 47 products with positive returns, most were hybrid products. Pure stock products accounted for only 4 percent.

Table 1.5

Performance of securities firms in 2011

Source: Securities Association of China (www.sac.net.cn)

Figure 1.4 The performance of asset management products developed by securities firms in 2011 Source: Securities Association of China (www.sac.net.cn)

Another potential profit of Chinese securities firms may be from direct investment business. Since September 2007, Chinese securities firms have been allowed to take direct investment business. Some direct investment subsidiaries were then established by securities firms for equity investment. By the end of 2011, 33 direct investment subsidiaries had been approved and established by securities firms (Table 1.6). Their registered capital for direct investment companies was RMB 25.66 billion Yuan (Figure 1.5). They managed five industrial funds of RMB 3.357 billion Yuan and two direct investment funds of RMB 2.547 billion Yuan. The total assets managed by the direct investment subsidiaries were RMB 31.564 billion Yuan. The direct investment funds are a type of private equity (PE) fund. Since securities firms have rich experience in investment banking, they like IPO to be the exit strategy of their equity investments.

Table 1.6

Direct investment subsidiaries established by securities firms from 2007 to 2011

Source: Securities Association of China (www.sac.net.cn)

Figure 1.5 Total registered capital of direct investment subsidiaries established by securities firms from 2007 to 2011 (RMB 100 million Yuan) Source: Securities Association of China (www.sac.net.cn)

Securities firms’ direct investment business is developing fast. From 2007 to 2011, the number of deals and amounts kept increasing. In 2011 the total investments were RMB 7.628 billion Yuan for 143 deals (Table 1.7). The investments exited mainly through IPOs. When GEM was launched in 2009, IPO was the first choice of those direct investments due to high P/E ratio and IPO prices on GEM. In 2009, six investments realized IPOs and received average returns of 401 percent. From fundraising to the IPOs they only took about 9 months (Table 1.8). 2011 saw 23 IPOs of the direct investment exit, with 568 percent return rates on average. Their investment cycle was 16.6 months. That means it takes only 16.6 months from fundraising to IPO. Direct investment has been an important profit source of securities firms. From 2007 to 2011, the net profits from direct investment increased by more than 100 percent. Direct investment has been a new source of securities firms’ profit growth.

Table 1.7

The deals and amounts invested from 2007 to 2011

Source: CVSource (www.ChinaVenture.com.cn)

A new business of securities firms is margin trading and selling short business. In March 2010, margin trading and selling short business were launched in mainland China. In October 2011, China Securities Finance Corporation Limited (CSFC) was established with registered capital of RMB 7.5 billion Yuan to be in charge of margin trading and selling short business. Its shareholders are SSE, SZSE and CSDCC. In 2011, the total trading value of margin trading and selling short was RMB 585.597 billion Yuan, accounting for only 1.39 percent of A-share trading value, which included margin trading of RMB 533.109 billion Yuan, and selling short of RMB 52.488 billion Yuan. The margin trading value was much higher than that of selling short business. Margin trading and selling short business can be a new revenue source of securities firms. In 2011, it brought revenue of RMB 3.191 billion Yuan, which was about 6.53 percent of brokerage business revenue and 2.34 percent of revenue of the securities sector. The revenue mainly came from commission and interest. The revenue from interest was RMB 2.438 billion Yuan, or 76.40 percent of the total revenue of margin trading and selling short, while commission contributed RMB 620 million Yuan, accounting for 19.43 percent of the total revenue.

The non-tradable share reform

Before 2005, China’s stock market had a distinct characteristic: most shares of listed companies were not tradable, because most listed companies were SOEs. Those shares were mainly either state-owned shares or legal person shares. By the end of 2004, the total A-shares outstanding were 714.9 billion, and 64 percent of them were non-tradable. Seventy-four percent of the non-tradable shares were state-owned shares. That created a dual equity structure of China’s stock market: the co-existence of state-owned stock and corporate stock as non-circulation stock, and public stock as circulation stock. Thus, for a listed company, unequal rights existed between shareholders of state-owned shares, legal person shares and tradable shares. The same share, due to different shareholders, had different prices and rights. The large portions of government ownership in China’s stock market make it difficult for the Chinese stock market to perform its function of effectively allocating capital to those companies with more efficient operations. The secondary market could not value the listed company accurately. That was a stock market with Chinese characteristics.

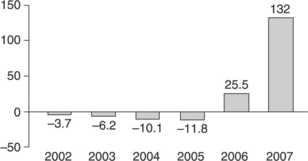

But, if the non-tradable shares were changed to be tradable, the supply of tradable shares would be greatly increased, which would hurt the tradable shareholders’ interests. The strategy of non-tradable share reform was that non-tradable and tradable shareholders were allowed to bargain over the transfer of non-tradable shares. The existing tradable shareholders were compensated in various ways such as bonus shares, cash and options by non-tradable shareholders. By this compensation, the state-owned shares of listed companies and non-tradable shares could obtain the tradable qualification. Non-tradable shares were then allowed to be tradable. The reform achieved great success in that way. By the end of 2007, 98 percent of listed companies had finished the reform. Thus, nearly all shares were tradable. The non-tradable share reform greatly encouraged the development of China’s stock market. A bull market was started. In only 6 months, the SHCOMP was nearly doubled. On 16 October 2007, China’s stock market reached a historic peak. SHCOMP stood at 6124.04. Securities firms, which had experienced loss from 2002 to 2005, had profitable years (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6 Net profits of securities firms from 2002 to 2007 (RMB billion Yuan) Source : SAC (www.sac.net.cn)

However, the non-tradable reform left one problem unsolved. When the green light for selling non-tradable shares was given, there was a sudden increase of a large quantity of share supplies, and numerous senior company officials raced to the counter to cash in. Although there was a lock-up rule that shareholders owning 5 percent or more of a company’s outstanding shares were allowed to sell after two years, and owners of less than 5 percent were allowed to sell after a year, the selling of the non-tradable shares still had a significant influence on the stock market. Many non-tradable shares emerged from their lock-up period in 2008 and 2009. That caused market panic to spread quickly. The stock market thus dropped by 50 percent in the first quarter of 2008. Following this, China’s stock market entered a bear market for years. In 2012, China’s stock market performed the most poorly in Asia in 2012. Its P/E ratio was only about 9 (by 3 December 2012), the lowest in Asia. About 92 percent of stock investors lost money. The SHCOMP was even lower than that in 2000.

Stock issuance system

The issuance system of China’s stock market can be divided into two stages. The first stage was before 17 March 2001, when IPO issuance was taken as an administrative approval system. The second period was after March 2001, since then the IPO issuance has been a qualification approval system. During the administrative approval system period, IPOs were under planning and determination by the authorities. From 1993 to 1997, the State Council gave local provinces IPO quotas for four times. Those provinces that received quotas could recommend their enterprises for approval to be listed on stock markets. Of course, the recommended enterprises were all SOEs. During the period, there was total control over share quota, or how many shares would be issued each year, which was implemented from 1993 to 1995. For example, a total IPO quota of 5 billion shares was given in 1993 and a quota of 5.5 billion shares was determined in 1994. During the period, about 200 companies were listed on the stock markets for fundraising of RMB 40 billion Yuan. From 1995 to 1997, both total shares and the IPO number were controlled. In 1996 and 1997, the total share quotas were 15 billion and 30 billion respectively. From 1995 to 1997, about 700 companies realized IPOs for fundraising of RMB 400 billion Yuan. The approval system had two procedures: local governments’ IPO approval and CSRC’s approval. When a company wanted to become an IPO, it first needed to obtain the approval of its local government or its supervisor, which recommended the company to CSRC for the final approval.

After 2001, a qualification approval system was implemented. The system included a channel system from March 2001 to December 2004 and a sponsorship system since February 2004. Under the channel system, CSRC gave the channel quota or IPO quota to main underwriters each year. When a securities firm was qualified to be a main underwriter, it could obtain a channel quota from two to nine, which allowed the underwriter to recommend two to nine IPOs. The channel system was still a quota control system. But it changed the IPO selection from the hand of governments to securities firms. Underwriters had power to select an IPO and took the risk at the same time. From February 2004, a sponsorship system was implemented. But the channel system was not given up immediately. It was still used until 31 December 2004. So between February 2004 and December 2004 was a transitional period: both channel and sponsorship systems were implemented. In February 2004, the Provision Measures on the Sponsorship System for Issuing and Listing of Securities were put into effect. The sponsorship system has been used since then. The system was aimed at improving the quality of public companies and better protecting investors’ interest. The sponsors are required to make sure that all financial information provided in the IPO prospectus is truthful. They continue to oversee disclosure information and to be sure it is valid for one or two years (depending on the trading board) after the company has floated its shares on stock exchanges. To be listed on stock exchanges, Chinese companies are required to obtain the endorsement of a qualified sponsor, whose duty is to make sure financial data and other information provided in IPO prospectuses are truthful. An underwriter or securities firm often acts as the sponsor of an IPO, which should have at least two qualified representatives for sponsorship to be qualified as a sponsoring institution. Meanwhile, a qualified sponsor’s representative is asked to be in charge of the detailed IPO work. The sponsoring work includes two stages: conducting due diligence on the listing application, and continuous supervision and guidance for the rest of the year and the following two complete accounting years. The authority expects sponsors and their representatives to guarantee quality and reduce risks of listed companies. But, due to the considerable personal interest involved, sponsors and their representatives may not strictly follow IPO regulations such as due diligence. While punishments for their moral hazard were not serious, such as representatives’ qualification being suspended for 6 months, IPO sponsors then faced a credibility crisis after a series of scandals. Reform of the sponsorship system has been requested by the public and investors. In future it may be expected that a registration system, a market-oriented system, will be implemented in stock issuance. The registration system is regarded as a better way to protect investors. If a company makes false statements in its prospectus, investors will make it pay a huge price through class actions and lawsuits. But there is concern over whether the government, CSRC, will be willing to hand over power.

Challenges facing the A-share market

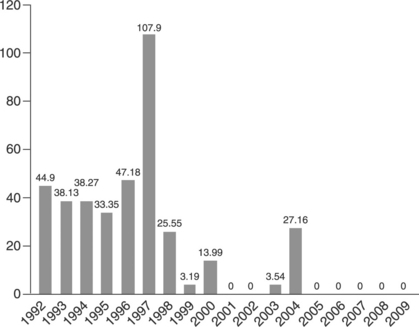

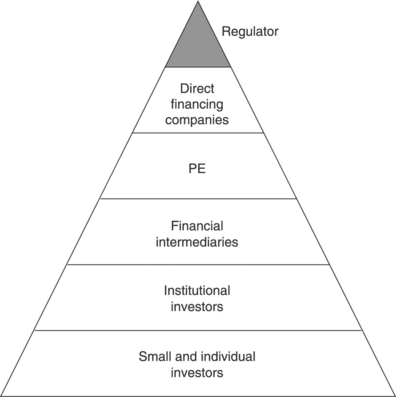

There have been many arguments over China’s A-share market for years. The following five problems probably cause most concern. The first is that China’s stock market focuses on fundraising much more than investment, and investment returns on stock investment are always poor in general. In developed capital markets, the bond market is much larger than the stock market. The bond market normally provides about 80 percent of the total direct financing. But China’s capital markets are an “inverted pyramid” kind of structure. The bond market is much smaller than the equities market. The stock market provides nearly 90 percent of direct financing. This benefits listed companies, particularly SOEs with low financing costs. When CSRC was established in 1992, the central government was reforming SOEs to improve their performance. In 1993 the State Council set the goal of solving the difficulties of SOEs, including the shortage of capital, within three years. The CSRC carried out the work for helping SOE financing. According to CSRC, at the early stage of the A-share market from 1984 to 1989, when the two national exchanges, SSE and SZSE, had not been established, the total financing of local stock markets was RMB 1.933 billion Yuan, or, on average, RMB 323 million Yuan each year. When the two national stock exchanges were established, from 1990 to 1996, the total financing of stock markets reached RMB 101.634 billion Yuan, or, on average, RMB 14.519 billion Yuan each year, which was 44.5 times the annual financing raised before 1990 (Table 1.9). After the central government took over control of the stock markets in 1997, from then to 2011 the total financing of China’s stock markets reached RMB 4.37 trillion Yuan or, on average, RMB 291.34 billion Yuan each year, which was about 20 times the annual financing in the years from 1990 to 1996 (Figure 1.7).

Table 1.9

The fundraised amounts of China’s stock markets from 1984 to 2011 (RMB 100 million)

Source: CSRC

Figure 1.7 The annual fundraising of China’s stock markets during different periods (RMB billion) Source: Data from CSRC

However, while China’s stock market provided more than RMB 4.3 trillion Yuan financing, the accumulated dividends for the past 21 years were only RMB 0.54 trillion Yuan. The investors’ returns in dividends were only about 2.7 percent, much lower than the annual deposit saving rates during the periods. In the stock markets, there are more than 100 million individual or small investors. They have financed listed companies such as SOEs while receiving poor returns. It could be argued that China’s stock market has a mechanism problem or defect. It focuses on the financing function more than the investment function.

Since CSRC was established in 1992, financing from the stock market has been an important part of SOE reform. Requiring SOEs, particularly large SOEs, to be listed on the stock market has been a goal of central and local governments. To encourage local companies to be listed on the stock market, local governments made a policy of providing the companies with subsidies and financial support for their IPOs. Fundraising from the stock market is better than from bank loans, since listed companies need not pay back the money raised, and the cost of using the capital is lower. China’s government has a simple reasoning for developing stock markets in that way: to drive China’s economic growth, it is critical to make SOEs perform well, which demands adequate financial support. For the Chinese government, to guarantee SOEs’ financing is to guarantee economic growth. So, capital allocation through capital markets is not determined by the market itself, but by the government. The performance of China’s stock market should first follow national economic policy rather than perform its own market function.

That China’s stock market performs its fundraising function much better than its investment function could also be explained by the phenomenon that, no matter how poorly the stock market performs or how low the IPO prices are, Chinese companies are still crowded for IPOs. For some companies, the total cost for their IPOs can be more than their annual profits. For example, Kailitai (300326: SZSE) was listed on the stock market in 2012. Its total IPO fees were more than RMB 50 million Yuan, while its net profit in 2011 was only RMB 37.13 million Yuan. Another company, Xinjiang Tisanshan Animal Husbandry Bio-Engineering Corporation Limited (300313: SZSE), paid expensive IPO fees which were about 128 percent of its annual profit, including the local government’s subsidy of more than RMB 6 billion Yuan. Once a company is listed on the stock market, it need not worry about the delisting problem, since this has not been well established or enforced for more than 20 years.

Since October 2007, the SHCOMP, the benchmark index of China’s stock market performance, has declined from 6124 points to less than 2000 points in June 2013, losing more than 70 percent. Xu (2013) pointed out that each investor’s account on the A-share markets lost about RMB 62,000 Yuan (US$10,000) on average for the past two years. But that happened against the background of China’s high economic growth rates, the highest in the world. So, the unique phenomenon is that, for the past 5 years, China’s economy performed best in the world in terms of GDP growth rates, while its stock market performance was one of the poorest as a whole in the world in terms of investors’ returns and index performance. In 2012, the SHCOMP was up only 3.17 percent, compared with the 7.3 percent upswing of the American Dow Jones Industrial Average and the 13.4 percent rise of the S&P 500 for the same period, even though the American economy was in crisis.

The second problem of China’s A-share market is in its issuance system, which has been criticized for years for its “three highs”: high IPO price, high amount of fund raising, and high P/E ratio. It is a non-transparent administrative approval mechanism rather than a market-oriented pricing mechanism. From 2009 to 2011, the average P/E ratios of IPOs on the A-share market were as high as 40. One reason for the high amount of fundraising is related to underwriters, who charge fees according to the amount of capital raised. Underwriters normally charge about 3 percent of the amount of capital raised for large cap stock on the main board, and 6 to 7 percent for GEM and SMEB stocks. The more capital is raised, the more fees underwriters can charge. The non-transparent issuance system and strong demand for IPO result in rent-seeking opportunities for some people. The “Wang Xiaoshi” case is an example. Mr Wang was a deputy division director in CSRC’s department in charge of supervising public offerings, and was charged with corruption because he was involved in selling the name lists of listing committee members, charging up to RMB 300,000 Yuan, to listing applicants for lobbying purposes.

Under the approval IPO system, the number of companies listed on the stock market during any period is controlled according to market performance and economic conditions. When the Chinese economy or stock market performs unsatisfactorily, IPO is often suspended. So far, there have been eight IPO suspensions due to poor performance of the stock market:

![]() from 21 July 1994 to 7 December 1994;

from 21 July 1994 to 7 December 1994;

![]() from 19 January 1995 to 9 June 1995;

from 19 January 1995 to 9 June 1995;

![]() from 15 July 1995 to 3 January 1996;

from 15 July 1995 to 3 January 1996;

![]() from 10 September 2001 to 29 November 2001;

from 10 September 2001 to 29 November 2001;

![]() from 26 August 2004 to 23 January 2005;

from 26 August 2004 to 23 January 2005;

![]() from 25 May 2005 to 5 June 2006;

from 25 May 2005 to 5 June 2006;

China’s government always tries to rescue the stock market when it performs poorly rather than leaving the market alone. The government has got used to interfering in the market. One way in which the government used to interfere with the stock market was to publish articles in People’s Daily, an organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. In 1990s, People’s Daily often published official articles on the stock market to give the market a direction. Suspending IPO has been a policy to stabilize the stock market. Each time IPO issuance was suspended, the stock market gave a positive response and went up. Since 26 October, 2012 the IPO has again been suspended on China’s stock market. By February 2013, there were 876 companies in line waiting for IPO approval, including 175 for the Shanghai main board, 363 for the Shenzhen main board and SMEB, and 338 for the Shenzhen GEM. Since it became unknown when IPO would be relaunched, some IPO applicants have withdrawn their applications, particularly GEM IPO applicants. By 10 May 2013, 745 IPO applicants were in line waiting for IPOs, including 176 for SSE, 322 for SZSE and 247 for GEM.

The IPO approval system has some serious flaws. It distorts the supply and demand relationship of IPO, and weakens the market mechanism of recourse allocation. Meanwhile, high IPO P/E ratios and weak supervision drive some companies to commit false accounting fraud. In fact, even though all listed companies are checked and approved by CSRC, their corporate performance and problems cannot be well identified. There have been a few cases of false accounting fraud by IPO applicants being identified by CSRC. When investors trust the approval of CSRC to buy the stocks of listed companies, they are often misled. There are some listed companies whose stock prices and performance start to deteriorate immediately after IPOs. The quality of Chinese listed companies may be indicated by those Chinese firms listed on American stock markets. In August 2012, the American Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) accused the Big Four, including Deloitte, PwC, E&Y and KPMG, which were auditing Chinese firms listed in the US, of violating the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) and the SEC Act of 1934. In addition, CSRC’s hard approval work also weakens its supervisory function as a regulator. It may be better for CSRC to hand over IPO approval to the market.

The third problem is its weak supervision system. China’s stock market has an incomplete enforcement system. The delisting mechanism has not been well established and enforced. So, corporate governance of listed companies is flawed. After SZSE and SSE were established in 1990, no listed company had been delisted for 10 years. It was on 23 April 2001 that the first listed company, PT Shuixian (600625: SSE), was delisted from the SSE. On 13 June 2001, PT Yuejinman (000588: SZSE) was delisted from the SZSE. From the official establishment of the stock exchanges in 1990 to having the first delisted company in 2001, China took more than ten years. For a listed company, its main concern is how to maintain its floated status. There was one listed company (600137: SSE) that changed its name 12 times within 15 years to stay floated. In addition, the securities class action system has not been established in China. So, Chinese investors may face higher risks in China’s stock market than Western investors in Western stock markets. The weak supervision and enforcement system make speculation and insider trading popular. The turnover rates of China’s stock markets are often very high. For example, in 2011, the rate was more than 1000 percent.

The fourth problem is in corporate governance of listed companies. China’s listed companies often have very poor corporate governance. Chongqing Business News reported on 16 July 2012 that more than 70 percent of independent board directors were part-time and normally nominated by the largest shareholders of listed companies. Thus, independent board directors were not independent and had little help in improving corporate governance. It reported that 40 percent of them were academics from universities; about 17 percent were from accounting firms or law firms; about 10 percent had a government background; and about 12 percent of them had an industry associate or official background (Figure 1.8). Some of them even served as independent board directors for as many as seven listed companies at the same time.

Figure 1.8 The background of independent board directors of listed companies Source: ‘Statistics data indicates that 70 percent of independent board directors of listed companies are part-time and more than 50 percent of them are government officers and scholars’, Chongqing Business News, 16 July 2012

China’s B-share market

Why was the B-share market launched?

When China undertook economic reform, there was a great shortage of foreign currency there. To help SOEs solve the shortage of foreign currency problem and to attract foreign investors, some SOEs were allowed to issue RMB-denominated shares to overseas investors, which were bought by foreign currencies. On 22 November 1991, PBOC and Shanghai Government jointly issued The Administrative Measures of Shanghai Municipality for Special Renminbi-denominated Stocks. On 5 December 1991, PBOC and Shenzhen Government jointly issued The Interim Administrative Measures of Shenzhen City for Special Renminbi-denominated stocks. Thus, the B-share board was launched. B-shares are common stocks listed on China’s stock exchanges, while being quoted and settled in foreign currencies. B-shares are listed on two exchanges: the SZSE, whose B-shares were quoted and settled in Hong Kong dollars; and the SSE, whose B-shares were quoted and settled in US dollars. The first B-share was issued by Shanghai Vacuum Electron Devices Company Limited. In November 1991, it issued one million special RMB-denominated shares at par price of RMB 100 or US$ 18.8 per share to overseas investors. On 21 February 1992, the stock was listed on SSE with the stock code of 900901. On 28 February 1992, the first B-share settled in Hong Kong dollars, which was issued by Shenzhen CSG Holding Corporation Limited, a renowned enterprise in glass, was traded on SZSE, with a stock code of 200012. From 1992 to 1994, 58 B-shares were listed on the stock exchanges. In trading, B-shares are the same as A-shares in a 10 percent price limit, while different in settlement of “T+3” by the China Securities Central Clearing & Registration Corporation (CSCCRC).

On 2 November 1995, the State Council issued Provisions of the State Council on Foreign Capital Stock Listed in China by Joint Stock Limited Companies. It was the first national regulation on the B-share board in China. By 1998, the B-share board had raised capital of about RMB 61.6 billion Yuan. From 1992 to 2000, there were 114 companies listed on B-share markets. After October 2000, the IPO of the B-share board was suspended. In 2003, the B-share IPO was relaunched for a short while. By 2012, there had been 107 B-shares in Shenzhen and Shanghai stock markets. On 15 July 1993, Tsingtao Brewery Company Limited became the first Chinese company to be listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange, and its share was called an H-share. Since then, many large Chinese SOEs are listed on the H-share market. When many Chinese companies issued H-shares on the Hong Kong stock exchange, overseas investors gradually lost interest in investing in the Chinese B-share market. Then the B-share board began to decline. Before 19 February 2001, B-shares were only sold to overseas investors. To rescue the B-share market, CSRC decided to open it to domestic investors. By the end of 2012, there were in total 109 B-shares, of which 54 were listed on the SSE and 55 on the SZSE.

The performance and problems of the B-share market

On 19 February 2001, the announcement was made that the B-share market would be opened to domestic investors, and domestic investors have been able to trade B-shares since 1 June 2001. The markets then saw a great surge. From 19 February 2001 to 1 June 2001, the B-share market index increased from 83.6 to 241.46, or by 189 percent. Domestic investors flooded the B-share market. For example, in that February, the total new accounts opened in the Shanghai B-share market were more than the total accounts opened for the past ten years. Meanwhile, many foreign investors, particularly foreign institutional investors, took the opportunity to withdraw from the markets with considerable returns. The semi-annual reports in 2001 indicated that foreign investors only accounted for fewer than 10 percent of the total investors. It was difficult to find foreign shareholders among the top ten shareholders of any B-share company. The B-share market had become a market dominated by domestic and individual investors. From June 2001, the B-share market started to decline. Meanwhile, no companies had been listed on it since 2000. But, at the same time, many Chinese companies started to realize IPOs on overseas markets, such as being listed in the Hong Kong stock market and the New York stock market. Since the B-share market was established, its performance had been acceptable until 2000. But, when the H-share market was well developed, the B-share market declined (Figure 1.9 and Figure 1.10), because H-shares are more attractive for overseas investors. Few institutional investors would like trading B-shares. The trading volume on the B-share was tiny compared with the main board. So, since 2001 the B-share market has gradually become inactive and lost its fundraising and investment functions. The B-share market has been at a crossroads.

The future of the B-share market

There are several solutions to solve the fate of the B-share market. Since Shanghai B-shares are denominated in US dollars and Shenzhen B-shares are denominated in Hong Kong dollars, the solutions for the two markets may be slightly different. For the Shenzhen B-share market, the listed companies may consider delisting from the market and then relisting in the Hong Kong Exchange (HKEX), because Shenzhen B-shares are denominated in Hong Kong dollars. Transferring B-shares to H-shares is easy, and welcomed by some B-share companies. In December 2012, China International Marine Containers (CIMC) became the first company to convert its Shenzhen-listed B-shares (200039: SZSE) into Hong Kong-listed H-shares (2039 HK). For those shareholders who rejected a Hong Kong listing, the company made a cash offer to buy back shares at HK$9.83 each share, which was a 5 percent premium over the stock’s last closing price of HK$9.36 on 13 July 2012. In fact, 90 percent of its B-share holders opted instead for the move to Hong Kong. The “B” to “H” success attracts other B-share companies to follow. China Vanke (SZSE 200002), the largest Chinese property developer, submitted its “B” to “H” transfer applications to both CSRC and HKEX in February 2013. Another pharmaceutical company, Livzon (2000513: SZSE), is also planning to move from B-share to H-share listing. To be relisted on the Hong Kong stock market, the B-share companies should meet the listing requirements of the Hong Kong stock exchange: for example, the latest year’s net profit no less than HK$ 20 million and revenue over HK$ 500 million, etc. For poor performance B-share companies, such that the market value is less than HK$ 1 billion and net profit is less than HK$ 100 million, moving from B-share to H-share can be difficult. There may be about 20 B-share listed companies that qualify for the “B” to “H” share change. For the Shanghai B-share market, its listed companies are denominated in US currency. Since China has a foreign exchange control policy, the “B” to “H” transfer involves some restrictions. There has been no such transfer yet. The second solution is to transfer B-shares to become A-shares. A B-share listed company is moved to be on the A-share market. This can be used for both Shenzhen and Shanghai B-share markets, particularly for Shanghai B-shares. For those companies that have issued both A-shares and B-shares, it is quite easy to convert their B-shares to A-shares.

One B-share company, Zhejiang Southeast Electric Power Company Limited (900949: SSE), announced its plan of “B” to “A” share change on 20 February 2013. Its controlling shareholder, Zhejiang Zheneng Electric Power, which holds 39.8 percent of the B-shares of Zhejiang Southeast Electric Power, would like to offer the price of US$0.799 per share to merge the B-share company, Zhejiang Southeast Electric Power Company Limited. Every Zhejiang Southeast Electric Power B-share will be converted to 0.74 to 0.86 A-shares of Zhejiang Zheneng Electric Power. The B-share to A-share conversion plan is pending approval from the shareholders of both companies and CSRC. If it is approved, it will be the first “B” to “A” case. Moving B-share companies to be on the A-share market may be the main solution for the Shanghai B-share market. Another solution for both Shanghai and Shenzhen B-share companies is delisting from the B-share market by purchasing back B-shares, since the B-share market has lost its fundraising function. They can buy back their B-shares and thus gradually decrease turnover on the already thinly traded board until delisted from the markets. Some B-share companies have already begun to buy back their B-shares.

In addition, because of the poor performance of the B-share market and because stock prices have deviated greatly from companies’ fundamental value, some B-share listed companies use buyback of their own shares to protect the interest of shareholders and to restore investors’ confidence. Shanghai Diesel Engine Co., Ltd. (900920: SSE) has made a B-share repurchase plan, which was approved by the shareholders on 22 February 2013. The company will repurchase no more than 86.8 million B-shares or 25 percent of the total B-share outstanding, in nine months, at a price of up to US$ 0.748 per share, which is 12 percent premium price. It can be expected that, in the next few years, China’s B-share market will disappear.

Small and Medium-sized Enterprise Board Market

China launched the Small and Medium-sized Enterprise Board (SMEB) on 25 June 2004 in the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. The first eight SMEs were listed for trading on that day. It is aimed at funding small and medium-sized enterprises, and particularly provides private firms with a financing opportunity. According to Yang (2012), China has about 42 million small and medium enterprises which contribute about 60 percent of national GDP and 80 percent of employment. It has long been difficult for them to obtain capital and financing for their development. Many of them have to depend on underground financial markets for financing. Compared with the main board, which serves large enterprises, particularly SOEs, SMEB mainly serves small and medium-sized private enterprises whose tradable share outstanding is less than 100 million. It was a preparation for launching GEM. The SMEB is the same as the main board in terms of IPO qualifications, but differs in share amount. Those companies with an IPO share outstanding of fewer than 100 million shares will be allowed for SME Board listing, while the enterprises with an IPO larger than that amount will be listed on the main board.

In fact, SMEB is a transition bridging the main board and GEM. On 15 September 2000, SZSE suspended IPOs to prepare for the launch of GEM. More than 2000 small and medium-sized enterprises were preparing for listing on GEM according to related regulations. However, GEM was not launched for various reasons, including the collapse of NASDAQ caused by the bursting of the dot.com bubble. To support those enterprises lining up for GEM, particularly those promising SMEs which were facing financial difficulty, SZSE was then allowed to launch SMEB to solve the financing problem of SMEs. On 17 May 2004, CSRC announced that SMEB would be launched. On 25 June 2004, eight SMEs were listed on SMEB. On the first trading day, their increase was 80 percent on average, with about 70 percent turnover rates. In June 2005, the 50th stock was listed on SMEB. After that, the IPO of SMEB was suspended for non-tradable share reform, in which SMEB was a pioneer. On 21 November 2005, the reform of SMEB was finished, and the experience explored for the reform of the main board. In June 2006, SMEB restarted IPO, and China CAMC Engineering Co., Ltd (002051: SZSE) became the first IPO after non-tradable share reform in China’s stock markets. Since then, SMEB has developed fast. In 2011, SMEB had 111 IPOs with fundraising of RMB 97.685 billion Yuan, accounting for 36.44 percent of the total market fundraising in the year. By the end of February 2013, 701 SMEs had been listed on SMEB.

SMEB is concerned with the growth potential of listed companies, and prefers SMEs in the high-tech field. Shenzhen supplies most listed companies for SMEB among Chinese cities. In general, the companies listed on SMEB have better corporate governance and quality than those on the main board. SMEB has a similar IPO benchmark to the main board, and higher than GEM. On 30 November 2006, CSRC issued The Special Provision on Suspension and Delisting of SMEB Stocks, which took effect from 1 July 2007. The delisting conditions are much stricter than for the main board. For example, if the trading volume of 120 consecutive trading days is less than 3 million shares or the close price for 20 consecutive trading days is lower than the stock face price, the stock should be delisted.

The Growth Enterprise Market

The launching of the Growth Enterprise Market

China Growth Enterprise Market (GEM), which is also known as ChiNext, was launched on 30 October 2009. It is aimed at providing fundraising for small and medium-sized high-tech enterprises with great growth potential. In fact, the launching of GEM was discussed as early as 1998 (Table 1.10). It was well prepared in 2000. However, it was suspended due to the bursting of the American dot.com bubble and the crash of NASDAQ in March 2000. The GEM has been reengineered since 2007. On 30 October 2009, the first 28 listed companies started trading. By the end of 2012, 356 SMEs had been listed on GEM. Since it is to serve young SMEs, the threshold is much lower than for the main board and SMEB. To be listed on GEM, a company should have a promising growth potential, and needs to meet some financial performance criteria; for example, the company is required to have net assets of more than RMB 20 million Yuan and should have operated for more than three years. Furthermore, the company should have stayed in the black for the two most recent consecutive years with combined profits of more than RMB 10 million Yuan. Alternatively, the company must have profits of over RMB 5 million Yuan for the most recent year on revenues of more than 50 million Yuan, plus an annual revenue growth of at least 30 percent in the previous two years. The threshold of GEM is not high. Most applicants can be approved for listing. According to CSRC, in 2011, 134 companies applied for GEM listing and 112 of them were approved. The IPO approved rate was 83.58 percent. GEM developed very fast. For the first two years, the number of listed companies had been 267. By 2012, there were 355 listed companies on GEM (Figure 1.11). This indicates that, every two or three days, a company was listed on GEM.

Table 1.10

The milestones of establishing China’s GEM market

| Time | The main events of launching GEM |

| 30 October 2009 | The first 28 stocks were in trading on the GEM. |

| 23 October 2009 | The launch ceremony of GEM took place. |

| 14 August 2009 | The country’s first issuance examination committee was established. |

| 26 July 2009 | CSRC started to accept applications for listing on the GEM. |

| 15 July 2009 | Investors were allowed to open accounts for investing on the GEM. |

| 5 June 2009 | The SZSE issued the final version of the rules for listing on the GEM, which took effect on 1 July 2009. |

| 8 May 2009 | The SZSE issued draft rules for listing on the GEM and solicited public opinion. |

| 31 March 2009 | CSRC issued the final version of the rules of an initial public offering and listing on the GEM, which took effect on 1 May 2009. |

| March 2008 | CSRC issued draft rules for an initial public offering and for listing on the GEM and started to solicit public opinion. |

| August 2007 | The State Council approved draft rules for listing on the GEM. |

| March 2007 | The SZSE’s technical preparation for the GEM was ready. |

| May 2004 | The SZSE established the SME board, which was seen as an important step toward the construction of the GEM. |

| February 2004 | The State Council decided to establish a multi-layer capital market system and to develop the GEM in order to finance different kinds of enterprises. |

| November 2001 | The NASDAQ index plunged greatly, caused by the dot.com bubble burst. The launch of China’s GEM was suspended. |

| October 2000 | The SZSE started soliciting opinion from society on the GEM rules. |

| September 2000 | The SZSE stopped issuing new stocks on the main board and was preparing intensively for setting up the GEM. |

| January 1999 | The SZSE handed in a proposal to CSRC on analyzing the establishment of the GEM. |

| December 1998 | China’s State Planning Commission proposed to the State Council to set up a stock market for growth enterprises as soon as possible. |

The performance of the Growth Enterprise Market

On the first day of trading, the 28 stocks performed wildly. To reduce speculation, the SZSE issued special suspension rules to regulate wild trading on the first day. Under the rules, if any stock fluctuates beyond 20 percent from its opening price, it will be suspended for 30 minutes; if a stock fluctuates again over 50 percent of its opening price, it will be suspended for 30 minutes; and if a stock fluctuates more than 80 percent from its opening price, it will be suspended until 2:57 pm, just three minutes before daily trading ends. On the first day’s trading, all 28 stocks were temporarily suspended within the first two hours of trading. Huayi Bros. Media Group (300027: SZSE) even saw a 122.74 percent surge from its IPO opening price.

GEM has very strong fundraising capability (Figure 1.12). The listed companies raised much more funds than they expected. For example, for the first two years since launch there were 267 listed companies. They planned to raise RMB 66 billion Yuan in total, while in fact they raised RMB187.4 billion Yuan, which was RMB 120.9 billion Yuan more than planned. That was three times the planned fundraising. Most of the over-raised capital was deposited in banks for making interest rates. For the current 355 listed companies, the average IPO price was RMB 29.69 Yuan. Their average IPO P/E ratio was 55.85. Their planned fundraising was about RMB 87.5 billion Yuan, while in fact they raised RMB 231.5 billion Yuan. The average fundraising for each listed company was RMB 402 million Yuan. Beijing has the most GEM listed companies. Among the 355 companies, 53 are from Beijing, accounting for 14.9 percent of all listed companies on GEM.

For the past three years, GEM has brought much wealth for shareholders and senior managers of those listed companies on GEM. It has made 735 millionaires and 2489 rich people who received wealth of more than RMB 10 million Yuan from GEM IPO. The launching of GEM provides PE an effective way to exit from their investments (Figure 1.13), and drives development of the PE industry in China. In 2010, the book returns of PE exit through GEM reached as high as 13.4 times on average. Among the first 28 listed companies, 23 received PE investments. But nearly all PE investments exit from the companies within three years of their IPOs. Li (2012) reported that, for the first three years since GEM was launched, there were 462 PE investment exits involving 248 PEs from 355 IPOs. The book returns were RMB 60.82 billion Yuan in total. The average return was 9.16 times for each PE investment.

Problems in the Growth Enterprise Market

There are some problems emerging on GEM. The first is that, once a company is listed on GEM, its corporate performance becomes poorer. For the 267 companies listed on GEM for the first two years, about 70 percent of them saw declining financial performance, and 20 percent of them even had negative growth rates of net profits. By 30 October 2012, three years since GEM was launched, there were 355 listed companies on GEM. But 65 percent of them were still below their IPO prices. In particular, 52 of them broke their IPO prices on the first day’s trading. Meanwhile, their growth potential was a concern. Most of the listed companies could not perform better than listed companies on the main board. The second problem was that, after IPO, senior managers of listed companies cashed out the companies’ shares that they held. Two hundred and three senior managers of 83 GEM listed companies cashed out 124 million shares of their companies for RMB 2.88 billion Yuan in total. For eight companies, the senior managers of each company cashed out more than RMB 100 million Yuan. Meanwhile, many of the senior managers resigned their positions after their companies’ IPOs. In 2011, there were about 200 senior manager resignations from GEM listed companies. Another problem is that it seems GEM does not welcome companies from manufacturing industries. For example, in 2011, 134 companies applied for IPOs on the GEM, and 22 companies were rejected, among which 15 were from manufacturing.

A debated problem is about the delisting system on GEM. For the first three years since GEM launched, there have been no delisted companies there. On 20 April 2012, SZSE issued the revised Rules Governing the Listing of Shares on the Chinext of Shenzhen Stock Exchange, which took effect on 1 May 2012. The rules stipulate delisting conditions, including:

![]() public warnings by the SZSE for three times over three years;

public warnings by the SZSE for three times over three years;

![]() the last annual report showing negative net assets;

the last annual report showing negative net assets;

![]() negative net profits for three consecutive years;

negative net profits for three consecutive years;

![]() the trading turnovers for 120 consecutive days are less than 1 million shares;

the trading turnovers for 120 consecutive days are less than 1 million shares;

![]() a closing price lower than the face value of stock for 20 straight trading days.

a closing price lower than the face value of stock for 20 straight trading days.

Shares of delisted companies will be traded on the Old Third Board that is operated under the supervision of the SZSE. So far, no listed company on GEM has met the delisting requirement. It may take a few years before anyone is punished by the new rules.

The Third Board Markets

The Old Third Board

The Third Board Market (TBM) includes the New Third Board and the Old Third Board. In July 1992, the Joint Office for Designing Securities Exchanges (later renamed as China Securities Market Research and Design Center) developed the Securities Trading Automatic Quoting System (STAQ) for trading legal person shares. In April 1993, China Securities Trading System Corporation Limited developed the National Electronic Trading System (NET) for legal person share trading. On 9 September 1999, they were closed by the government. On 12 June 2001, the Securities Association of China developed a Share Transfer System (STS) for trading tradable shares of those companies listed in NET and STAQ. On 16 July 2001, two companies named Daziran and Shenzyang Changbai, which were previously listed in STAQ, started share trading. So, STS was formally in operation. The STS experienced two expansions. The first was to accept delisted companies from SSE and SZSE. On 29 August 2002, CSRC decided to allow those delisted companies from the two exchanges to be traded on the STS. It was called the Third Board at the time, and the Old Third Board later. It was an OTC market. In 2002, the trading on the board was very active. The total trading volume was 600 million shares for RMB 2.21 billion Yuan. From 2003, trading declined. By the end of 2005, there were 42 listed companies and 46 stocks (Table 1.11). Some listed companies issued both A-shares and B-shares.

The New Third Board

The new Third Board is also called National Equities Exchange and Quotations. On 16 January 2006, the unlisted companies of Zhongguancun Science and Technology Park in Beijing, also called Chinese Silicon Valley, were allowed to trade their shares for a trial. That was called the New Third Board trial. It was a trial version of the OTC market based in Zhongguancun Science Park. On 23 January 2006, Beijing iReal Technological Corporation Limited became the first company from Zhongguancun Science Park to be listed in the New Third Board. The New Third Board is aimed at high-tech enterprises in Beijing’s Zhongguancun Science Park to finance their growth via share transfers to investors. The companies involved were high-tech companies. Most companies trading on the New Third Board had less than 50 million Yuan ($7.88 million) in net assets. The threshold for being listed on New Third Board was low. The fundamental requirements for the listings include valid existence for two years, prominent main business, sustainable profitability, reasonable corporate governance, legal compliance of share issuance and transfer, and a certificate of share transfer pilot company granted by Beijing Municipal Government.

In 2011, CSRC promoted the policy of accelerating the development of a multi-level capital market system for direct financing, particularly for SMEs. The New Third Board was to build a nationwide OTC trading market to serve high-growth SMEs and microenterprises, and to standardize the trading as well as bring order to OTC trading. In August 2012, the New Third Board Trial was expanded to other regional science parks, such as Tianjin Binhai Hi-tech Industrial Development Area, Shanghai Zhangjiang Hi-tech Park, and Wuhan Donghu New Technology Development Zone. This was called the New Third Board Trial Expansion. By the end of 2012, there were 200 listed companies in the New Third Board, including 175 companies from Zhongguancun Science Park, seven from Tianjin Binhai Hi-tech Industrial Development Area, eight from Shanghai Zhangjiang Hitech Park and ten from Wuhan Donghu New Technology Development Zone. Ninety percent of them are high-tech companies. The total shares outstanding were 5.527 billion and trading volume was 11.455 million shares in 2012. The average P/E ratio for the New Third Board in 2012 was 46. The total fundraising was RMB 2.282 billion Yuan.

After years of trials in several cities, the New Third Board was officially established. It was a national share transfer system for small and medium-sized enterprises and was launched on 16 January 2013 in Beijing. It is formally called National Equities Exchange and Quotations (NEEQ). It is an exchange under the management of National Equities Exchange and Quotations Corporation Limited. The shareholders include SSE, SHSE, SD&C (China Securities Depository and Clearing Co., Ltd), SHFE (Shanghai Futures Exchange), CFFEX (China Financial Futures Exchange), ZCE (Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange) and DCE (Dalian Commodity Exchange). The four pilot zones mentioned above have been incorporated into the NEEQ. The official launch of the New Third Board is a critical step toward nurturing the nationwide over-the-counter market in China. It is a supplement to the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. By 8 March 2013, 212 companies had been listed on the New Third Board. The trading is not daily, but is taken on each Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

The main regulations to supervise and regulate the New Third Board are Interim Measures for the Administration of National SME Share Transfer System Co., Ltd., which was issued by CSRC on 31 January 2013, The Business Rules of National Equities Exchange and Quotations, which was issued by National Equities Exchange and Quotations on 8 February 2013, and The Measures for the Supervision and Administration of Non-listed Public Companies, which was issued by CSRC on 28 September 2012. In the next five years, the number of listed companies in the New Third Board is expected to be more than 5000 and the total market value more than RMB 1 trillion Yuan, which provides investors, investment banks and other intermediaries a good opportunity. By the end of 2012, 63 securities firms had qualified as underwriters of the New Third Board. In addition, the New Third Board also attracts many PE funds. Due to the fierce competition in the PE market, the New Third Board has become a field in which PE institutions like to invest.

China’s International Board

What is the International Board?

China is preparing to launch an International Board (IB), which is to allow overseas companies to issue Yuan-denominated shares on the SSE. Since the target listing companies register abroad and have a foreign background, such as HSBC, it is thus called on the stock market the International Board. The proposal for launching the board first emerged in 2009. On 29 April 2009, the State Council issued a document to promote building Shanghai into a global financial hub. The document proposed to allow foreign companies to issue Yuan-denominated shares in China. The Shanghai government then issued a document to support IB building. On 3 April 2010, the central bank, PBOC, issued 2009 International Financial Markets Report, in which preparing the launch of the IB was proposed again.

The IB building has attracted many multinational firms. Some famous companies have shown a strong interest in being listed on the IB, such as HSBC, Unilever, etc. The first foreign company to show interest in being listed on the IB was the world famous car maker, Daimler-Benz. Four kinds of companies may be eligible for the board. The priority may go to red chips, such as China Mobile. Red chips are those companies registered overseas and traded in Hong Kong, while the majority of their business is on the mainland. There are 407 red chips, 38 of which may meet CSRC’s threshold to list on the IB. The IB can provide them with a way to gain back A-share markets. They are expected to be the main force of the IB.

The second batch may be those companies with a Hong Kong, Macao or Taiwan background which are famous and profitable, particularly those that have been listed on the Hong Kong stock market, such as Hutchison Whampoa. The next group may be those famous multinationals that have been in China for years, such as Volkswagen, Coca-Cola, and Procter & Gamble. Those foreign companies with good financial performance which have not been in China may also be eligible for IB. According to the proposed rules, a foreign registered company seeking a listing on the IB should have a combined three-year net income of more than 3 billion Yuan, and a market capitalization of more than RMB 30 billion Yuan ($5.5 billion). More importantly, the proceeds of the IPO can only be used abroad. For investors, a qualified limited partners (QFLP) program may be launched for foreign investment in the IB.

Why is the International Board planned for launching?

China is developing a multi-layered capital market to meet the financing demands of different companies. For example, small and medium-sized firms can raise funds through the New Third Board or GEM, while large firms can obtain finance through the A-share market. But, since China undertook economic reform, little attention has been given to foreign companies’ fundraising in China. Many foreign companies in China face a problem of few funding channels. The IB can help them directly raise capital on the mainland and support their business development. Another reason for launching IB is to improve the mechanism of the A-share market. Since many companies that target listing on the IB may have already been listed in key global stock markets where information disclosure is much more stringent than in the Chinese stock market, the IB can help achieve high standards for Chinese companies’ information disclosure. Furthermore, it may help the A-share market to adjust its high valuation. Big foreign companies generally have a lower P/E ratio than domestic companies listed on the A-share market. There is an argument (Li, 2010) that IB launching could promote long-term value-oriented investment strategy in China and reduce the volatility of China’s stock markets by providing Chinese investors with plenty of blue chips. For the Shanghai government, launching the IB is to improve the financial importance of Shanghai. It will help Shanghai to become a global financial center by 2020, as planned. China can use the IB as a way of improving her global influence and image. When the IB uses RMB for stock pricing, this Chinese currency may be more widely recognized by global markets, which will further promote the RMB’s global influence. Thus, the IB may be used to help the internationalization of the RMB, and may be a part of the rise of China.

However, there are some arguments against launching the IB. For example, Wang (2012) argued that it is more urgent to support financing Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises than foreign companies. In fact, it is impossible to avoid a negative influence on A-share markets if the IB is launched. At the least, the IB can divert capital flow from the main board and cause negative physiological effect on A-share markets. Some practical problems are unsolved. The first is developing a legal system to regulate the IB. Since all companies listed on the IB will be foreign companies, it is questionable whether CSRC will be able to supervise them well at the current stage without complete and developed legal documents and regulations on the IB. The laws to regulate the main board are Securities Law and Company Law, which are both for domestic companies. It is obvious that they are not applicable to IB listing companies, which are registered in foreign countries and may conduct most of their business there. To launch the IB, it is necessary to have enough legal preparations. Besides, China’s current stock markets still have some unsolved institutional and mechanism problems, such as in IPO mechanism and stock market supervision. So, it is arguable that the IB is not so necessary for China’s stock markets in the short term. It may be better to launch the IB after the Chinese currency, RMB, has made further progress in its internationalization.

Some arguments on the International Board launching

When the IB was proposed, two basic questions emerged: which currency is used for stock pricing, US dollar or Chinese RMB? Which accounting principle is used, Chinese Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)? For the first question, there is an opinion to support using the US dollar for pricing. The argument is that pricing in US dollars can benefit the A-share market by channeling little capital to the IB from the main board. However, CSRC has decided to use RMB for IB pricing. Mr Dong Daochi, the Director of the International Cooperation Department of CSRC, said on 21 May 2011 at Shanghai Lujiazui Forum that the IB would use RMB for pricing in his talk at the discussion titled “The Two-Way Opening of China’s Financial Market in a New Era.” The second question is under discussion and has not been answered yet. Different accounting standards can cause a company to have different financial performance. Thus, choosing the accounting standard is a critical problem for launching the IB. Since it is China’s IB, it may be necessary to apply China’s GAAP. Another important argument is the timing of launching the IB. Even though the exchange has completed its preparations for the board, including regulations, this does not mean that the IB should be launched immediately. Each time IB launching is mentioned by CSRC, the main board immediately reacts negatively. The main worry is that IB may channel away investors and capital from the main board. Another worry is that international company valuations are much lower than those Chinese companies listed on the A-share market, which may drive the prices of A-shares down. So, IB launching needs to consider the performance of the A-share market.

Since SHCOMP is at a historical low, standing at less than one-third of the index peak of 6124 in October 2007, and IPO has been suspended since October 2012, 2013 is not the right time to launch the IB. Meanwhile, economic performance is another issue to consider. IB may only be launched when the economy is growing in a stable manner. In fact, the IB launch should also consider the total money supply of China. China’s M2, the total money supply, has been about 200 percent of GDP. The IB may be a way to help China to solve the over-supplied currency and fight potential high inflation. CSRC now takes a very cautious stance. On 11 November 2012 the chairman of CSRC, Mr Guo Shuqing, said at a news conference on the sidelines of the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China that there was no plan to launch the IB in the short term. So, it is quite unlikely that the IB will be launched in 2013.

Discussing the problems that China’s stock market is facing