Structure of higher education

Abstract:

The development of higher education in China is mainly reflected in changes in its structure. First in this chapter, the categories of HEIs are discussed on the basis of forms, types of ownership, functions, disciplines and key or non-key HEIs. Then the structure of higher education is analyzed from the perspectives of forms, levels, and disciplines. Finally, gender structure and regional structure of higher education are briefly covered. Generally, China has undergone great changes in the structure of higher education in the past three decades, and the most prominent features are the diversification and the adaptation to the development of market economy.

The development of higher education in China in the past three decades is not only reflected in the great changes in education scale, but more importantly, in the major or fundamental changes in structure. Generally speaking, China’s higher education structure is becoming more reasonable and optimized, and these changes meet the requirements and promote the development of the economy and society. In July 1994, the State Council issued ‘Suggestions on the Implementation of “Outlines of Educational Reform and Development”,’ saying that

different types of HEIs at different levels should have different development goals and priorities and establish their own characteristics. All kinds of short-cycle courses in undergraduate education should enlarge their scales to a proper extent, making full use of such forms as television, radio, correspondence and so on to train forefront personnel needed for the production in the majority of rural area, township enterprises and small and medium enterprises. Normal courses undergraduate education should focus on improving the quality, and master and doctoral education should basically keep a domestic foothold. Talents on fundamental subjects should be trained and at the same time, importance should be attached to the training of high-level talents urgently needed by socialist construction.1

This chapter will study the following three aspects: categories of HEIs based on forms, types of ownership, functions, disciplines and key or non-key HEIs; the structure of higher education, including forms, levels and disciplines; and the gender and regional structure of higher education. The description of these structures and their changes reflects the situation and direction of development of higher education in China.

Categories of HEIs

During the first decade of reform and opening up, China’s higher education stalled. Meanwhile, the fast development of the economy and society required not only a large number but also a variety of high-quality personnel. With the further development of the economy and the reform and development of higher education, the trend of diversification of higher education became obvious and diversification of HEIs became a tendency too. HEIs in China can be classified based on the forms, ownership, disciplines, functions and key or non-key HEIs.

Form-based categories of HEIs

Prior to 1949, the form of higher education had been very simple. After the foundation of the PRC, to promote the development of higher education, a wide range of adult higher education emerged, and correspondingly a variety of HEIs appeared, such as the Workers’ University, the Amateur University of Workers, the Peasants’ University, colleges of education, Teachers’ College, College of Administrative Cadres, Radio and TV University, and the University of the Elderly. Before 2001, China’s HEIs had basically been divided into regular HEIs and adult HEIs according to the forms of education they provided, and other private HEIs were separated as a third category. But actually, regular HEIs may provide adult higher education, and adult HEIs may also offer regular higher education.

Regular HEIs can be subdivided into HEIs Providing Degree-level Programs and Non-university Tertiary training (Short-Cycle Colleges). The former are entitled to enroll students in normal courses, while the latter are only entitled to enroll students in short-cycle courses. Of course, not all HEIs Providing Degree-level Programs have the right to provide postgraduate programs. Generally speaking, the more prestigious and the higher the quality of teaching and teaching staff, the more types of graduate programs a university is entitled to provide. At present, many prestigious universities no longer have the right to provide short-cycle courses. Non-university Tertiary are mainly Tertiary Vocational-Technical Colleges. The number of each category of institutions in 2009 is shown in Table 3.1.

In 1980, the total enrollment of regular HEIs in China was 1.14 million, while that of adult HEIs was 0.50 million, and the former was 2.3 times the latter; then the proportion of the enrollment of regular HEIs decreased and in the mid-1980s, the number of students at regular and adult HEIs became similar. Since then, the proportion of enrollment of regular HEIs has been increasing, and became 1.3 times that of adult HEIs in 1999. Entering the 21st century, with the expansion of higher education, enrollment of regular HEIs has been increasing rapidly and that of adult HEIs has decreased.2

From Table 3.2, it can be seen that regular HEIs have been expanding and adult HEIs have been shrinking during the last decade. From 1997 to 2009, the number of regular HEIs increased from 1,020 to 2,305, while that of adult HEIs were reduced from 1,107 to 384; floor area of regular HEIs increased from 144 million to 632 million square meters, while that of adult HEIs dropped from 31.61 million to 19.97 million; the number of full-time teachers of regular HEIs increased from 0.40 million to 1.30 million, while that of adult HEIs decreased from 0.10 million to 0.05 million; and total enrollment of short-cycle and normal undergraduates of regular HEIs increased from 3.17 million to 26 million, while that of adult HEIs has not increased significantly.

In 2009, there were 21,132,684 students receiving regular higher education and 4,871,564 receiving adult education at regular HEIs, and the enrollment of regular and adult higher education at adult HEIs was 313,886 and 541,949 respectively. The enrollment of regular HEIs was 30.4 times that of adult HEIs. Teaching staff at regular HEIs were 2.11 million, an increase of 60,422 over the preceding year, of which 57,797 were full-time teachers. Teaching staff at adult education were 84,196, a decrease of 5,696 over the preceding year, of which 2,825 were full-time teachers.3

The main reasons may be as follows: First, regular higher education has always been what people aspire to, but the chances were limited from the establishment of the PRC to the beginning of the opening up. So a large number of people had to choose adult higher education, a supplement of regular higher education. As a result, fewer people are likely to receive adult higher education when regular higher education expands. Meanwhile, with a history of 30 years’ adult education in China, older generations who previously lacked educational opportunities now have access to education. Second, adult education is also offered by regular HEIs, which occupy more high-quality educational resources. A considerable proportion of the teachers at adult HEIs are part-time, most of whom are not as skillful or experienced as full-time teachers. For instance, the proportion of professors in full-time teaching in 2009 was 10.67 percent at regular HEIs and 3.91 percent at adult HEIs (see Table 3.3). Also, the teaching quality of adult HEIs is not as high as regular HEIs. At the same time, such infrastructure as libraries at adult HEIs is rather inferior to that of regular HEIs.

Ownership-based categories of HEIs

China’s HEIs had been state-owned or government-owned since the nationalization of private universities in 1950s till the establishment of the first private HEI in 1980, although the administration of HEIs changed from sole direct management of the central government to shared management between the central government and the local government in 1963.

China began to encourage social organizations to run schools and the policy was written into the Constitution in 1982. Private or non-state HEIs began to grow. Related statistics in 1989 showed that there were more than 200 private HEIs with a total enrollment of about 2 million in more than a dozen cities such as Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai.4 According to the China Daily, there were more than 400 HEIs run by social forces in 1992.5 However, due to lack of supporting policies and norms, the main tasks of private HEIs were to provide non-academic training and classes for self-study examination. Private HEIs were just supplementary, while public HEIs were predominant.

‘Higher Education Law of the People’s Republic of China’ and ‘Action Plan for Vitalizing Education for the 21st Century’ issued in 1998 and ‘Decision on Deepening the Reform of Educational System and Promoting Quality Education’ released in 1999 provided strong legal and policy support for the development of private higher education. Another form of private higher education (independent institutions) sprang up and developed quickly.

The NPC Standing Committee passed the ‘Private Education Promotion Law’ in 2002, and the MOE issued the ‘2003-2007 Action Plan for Invigorating Education’ in 2004. These two documents defined the policy of positive encouragement, vigorous support, correct guidance and administration in accordance with law to private education in China. Government at all levels brought the development of private education into line with national economic and social plans. With the rapid development of private education, mutual complementation, fair competition and common development between public and private HEIs were formed. Private HEIs have become an important part of the higher education enterprise. In 2009, there were a total number of 2,305 regular HEIs in China, of which 656 were private and 322 were independent institutions.6 In addition, there were two adult HEIs and 812 other private tertiary education institutions (see Table 3.1) Private regular colleges and universities and independent institutions are the main forms of private HEIs, with 4,359,808 regular normal and short-cycle undergraduate students and 101,587 adult students, accounting for 20.33 percent and 1.88 percent of the corresponding number of students in 2009 (see Table 3.4).

In 2010, there were 350 private regular HEIs, 316 independent institutions and two private adult HEIs in total. Private HEIs are mainly short-cycle colleges. For example, there are 302 short-cycle colleges, mainly tertiary vocational-technical colleges, and only 48 universities or colleges were entitled to enroll normal courses students in 2010.7 Despite lack of statistical data, it is generally known that there is a great gap between private HEIs and public HEIs in many aspects such as quality of candidates and teaching staff.

Function-based categories

Teaching and research are the two main functions of today’s HEIs. Nowadays, HEIs across the globe generally position themselves on the basis of their basic functions. Categories of HEIs usually include research universities, teaching-research institutions and teaching institutions, each of which reflects certain options of the institutions’ basic functions.

Over the last decade, with the rapid expansion of higher education, some colleges that provided short-cycle courses were upgraded to universities and the others became vocational colleges (Non-university Tertiary). With the return of the research function of HEIs and the carrying out of the ‘211 Project’ and ‘985 Project,’ the original classification of HEIs could not keep pace with the development. Combining the international classification method and the reality in China, some scholars and HEIs re-classified HEIs according to the functions they performed. Different scholars’ categorization of HEIs varied, and the most generally accepted categorization was that the HEIs in China could be divided into research universities, research-teaching universities, teaching universities and vocational colleges.

Categorization based on functions has been generally recognized by the society, the academic circles and HEIs, and many HEIs define or reconsider their development goals and orientation accordingly. There were 768 regular HEIs providing normal courses and 1,215 providing short-cycle courses in June 2009.8 By and large, the ‘985 Project’ universities (see Appendix) can be classified as research universities, accounting for about 5 percent of the total number of HEIs Providing Degree-level Programs around the country and roughly belonging to the top 40 universities in China. The ‘211 Project’ universities (see Appendix) which are not ‘985 Project’ universities and some key provincial universities can be broadly classified as teaching-research universities, accounting for about 25 percent of HEIs Providing Degree-level Programs and roughly belonging to the top 200 universities, while the following 500 or so universities/colleges can be counted as teaching universities.9 There were about 1,047 vocational and/or technical colleges in June 2009, and the 387 adult HEIs can be regarded as teaching or vocational HEIs.10 Of course, most universities may change positions with time, which will not be officially reported to the public or the administration section, so it is difficult to obtain the exact data for each category.

Discipline-based categories

Discipline-based classification is an important traditional way to classify HEIs in China. In 1952, China began to reform higher education following the Soviet model in setting HEIs, majors and so on. While retaining a small number of liberal-arts-intensified universities, such disciplines as engineering, agriculture and medicine were separated from most comprehensive universities to establish specialized colleges. While there were a total number of 49 comprehensive universities in 1949, only 14 were left in 1953. As a result, a large number of single-discipline-based colleges were established, of which colleges of engineering and normal colleges occupied the majority. To be specific, there were 38 Natural Sciences and Technology, 33 Teacher Training Institutions, 29 colleges of Agriculture and Forestry Institutions, 6 Finance and Economics Institutions, 4 Political Science and Law Institutions, 8 Language and Literature Institutions, 15 Art Institutions, 4 Physical Culture Institutions, 3 Ethnic Nationality Institutions and 1 other institution.11 Since then, comprehensive universities, multidisciplinary institutions and singlediscipline or specialized colleges constituted the three major categories of HEIs in China, with single-discipline colleges in the majority.

This pattern of overspecialization was convenient for administration and distribution of resources, but was not conducive to the cultivation of competent personnel, integration of different disciplines, or achievement of major comprehensive research work. So China began to re-establish a number of comprehensive universities and initiate a reform toward comprehensiveness within most HEIs in the 1990s. But even in 1997, there were still too many single-discipline institutions and too few comprehensive universities, with only 72 comprehensive universities and 950 single-discipline or multidisciplinary institutions among the 1,022 HEIs in China.12 In the late 1990s, through the merging of institutions and the collaboration between institutions and other operating forms, a variety of comprehensive universities were reshaped.13 In 2009, among the 2,305 HEIs, 547 were comprehensive universities and the percentage of single-discipline or multidisciplinary colleges decreased. Judging from the percentage of enrollment, school size of comprehensive universities was slightly larger, for the 23.73 percent HEIs enrolled 25.67 percent of undergraduate students (see Table 3.5).

Key universities and non-key HEIs

To meet the need of the economic and social development, HEIs can be classified as key universities, and other HEIs on their basis and comprehensive strength, which was a way of classification with Chinese characteristics. This classification has positive significance so that the country could focus its limited finance and resources to support some universities or disciplines which are of great help to the development of the economy, science and technology and society, and to the universities to catch up with or surpass world-class universities as soon as possible.

In 1978 the State Council decided to restore the original 64 key colleges and universities, and eventually increased the number to 88. In 1981, there were 96 key universities. Since the function of research was emphasized, the need of HEIs for resources increases day by day. In 1985, presidents of several well-known universities jointly proposed to the central government to ‘enclose 50 universities or so into a major national project.’ The proposal was taken seriously, and a number of universities were made key universities of investment during the ‘7th Five-Year Plan’ (1986–1990) and the ‘8th Five-Year Plan’ (1991–1995). Thus the building of key universities was underway.

The economic development put forward higher requirement for science and technology and top talent in the 1990s. To focus the funds, the state established two significant projects on higher education construction – the ‘211 Project’ and the ‘985 Project’ – which led to noteworthy achievements in building high-level universities.

The 1993 Outline put forward support to about 100 colleges and universities, striving to build them into world level universities at the beginning of the 21st century, and the list of these universities was made by the SEDC in July. The ‘211 Project’ was launched in 1995. Over the last decade or so, the number of ‘211 Project’ universities has increased and the latest data showed that there were a total number of 113 in 2010.14 The project has achieved great success, namely, the overall strength of ‘211 Project’ universities, including teaching staff, cultivation of students and research work, was enhanced to a great extent, narrowing the gap between these universities and the world-class universities. Significant achievements were made in discipline construction, with a number close to the international advanced level, and the efficient public service system of higher education was initially built up. Innovative capacity of universities was improved, bringing about a large number of outstanding achievements, and the international influence of Chinese higher education was increased. 15

At the Centennial Ceremony of Peking University in May 1998, Jiang Zemin said, ‘A number of advanced, first-class universities of the world must be built up in China in order to realize modernizations.’ The MOE then decided to focus on the construction of nine universities, including Peking University and Tsinghua University, helping them to rank closer to the world-renowned universities. In the following years, the MOE included in batches the well-known universities in China into the ‘985 Project.’ Thirty-four universities were included in the first phase (1998–2003), and five more in the second phase (2004–2007). In 2004, the target of the project was changed into building a set of platforms for scientific and technological innovation and striving to build a number of world-class universities and a number of internationally renowned highlevel research universities.16 At present there are 44 ‘985 Project’ universities.

To promote the formation of a group of world-class disciplines and academic development, an innovative platform for dominant disciplines of the ‘985 Project’ was officially launched in 2006. These universities were chosen from universities affiliated to the ‘211 Project’ but not the ‘985 Project.’ Currently, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications and seven other universities are part of the project. In January 2007, the MOE and the National Scholarship Council officially launched the project of ‘sending government-sponsored post-graduate students abroad for academic pursuits for the purpose of building high-level universities,’ which would sponsor about 5,000 postgraduates yearly from the ‘211 Project’ and the ‘985 Project’ universities to study at world-level universities from 2007 to 2011. According to the list of 2010, students were from more than 70 key universities.17

The ‘211 Project’ and the ‘985 Project’ played an important role in promoting the rapid development of higher education concerning improvement of conditions of HEIs, personnel training and research work and in driving the deep-seated reform of higher education and innovation.

This classification of HEIs has a great impact on enrollment and graduate employment. As far as enrollment of programs at the same level is concerned, the minimum scores for key universities are higher than those for average colleges, which are higher than those for independent institutions and other private HEIs. In general, graduate employment rates and average initial wages of graduates from key universities are higher than those from average universities and vocational colleges.

Structure of higher education

In order to meet the requirements of economic and social development, China has been attaching great importance to the adjustment and optimization of the higher education structure and great achievements have been made since the reform and opening up. The forms of higher education mainly include regular higher education, adult education and state-administered examinations for self-directed learners (Self-study Examination of Higher Education); levels of higher education include specialized higher education (short-cycle courses), undergraduate education (normal courses) and postgraduate education; disciplines can be divided into several levels, the most general of which include 12 categories, namely philosophy, economics, law, education, literature, art, history, science, engineering, agriculture, medicine, and management.

Forms

Regular higher education and adult higher education are the complementary and most important forms of higher education in China, both of which have developed tremendously since the reform and opening up.

The economic development that started in 1978 in China generated an increasing need for a large number of high quality personnel. Meanwhile, lots of individuals had the strong desire for higher education because of the standstill caused by the ‘Cultural Revolution.’ However, the state was incapable of promoting the rapid expansion of regular higher education all at once. Under such circumstances, various forms of adult higher education in China were restored. In June 1987, the State Council approved the ‘Decision on the Reform and Development of Adult Education’ brought forward by the SEDC. In the past 30 years, adult higher education presented basically the same development trend with regular higher education. Prior to 1998, adult education and regular higher education had been of similar size, each accounting for about half of higher education in China. Because of the expansion of regular higher education since 1999, the size of adult education has reduced to about one third of that of regular higher education, occupying a smaller share in higher education. Of course, the development of adult education is closely related to that of adult HEIs, but is not the same, for, as mentioned above, most regular HEIs provide adult education and some adult HEIs provide regular education too.

Self-study Examination of Higher Education is an important part of higher education in China. In 1981, the MOE formulated the ‘Interim Measures of Self-study Examination of Higher Education.’ This examination started to be carried out in 1981, and a considerable number of people participate in it every year. Until the second half of 1988, 5.6 million people had participated in this examination in more than 200 majors all over China, and about 280,000 had obtained short-cycle or undergraduate certificates. In 2007, 9.55 million people registered in the examination in 22.16 million subjects, an increase of 0.62 percent and 2.38 percent respectively compared to 2006. Of these, 5.67 million people (59.41 percent) were normal courses applicants, and 3.88 million (40.59 percent) were for short-cycle courses; 13.08 million subjects (59.04 percent) were normal courses, and 9.08 million (40.96 percent) were short-cycle. In 2007, the National Examinations Board revised 20 and initiated 22 subjects with unified national plans, and approved 76 and recorded 364 provincial majors for self-study examination. The nation had set up self-examination in 796 majors, among which 141 (17.7 percent) were with unified national plans issued by the National Examinations Board, 347 (47 percent) were undergraduate programs and 449 were short-cycle ones. It can be seen that the percentage of short-cycle programs is decreasing while that of undergraduate programs is increasing.18

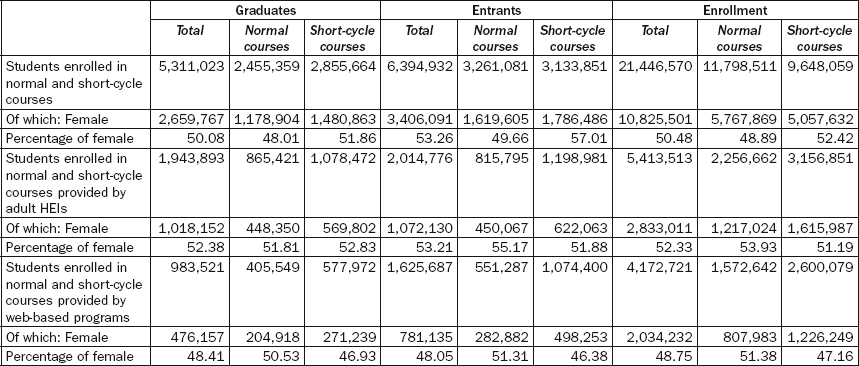

In 2009, entrants of short-cycle and normal programs of regular higher education totaled 6.39 million, an increase of 0.31 million compared with the preceding year; total enrollment was 21.45 million, 1.24 million more than the preceding year, with an increase of 6.14 percent; and the number of graduates was 1.40 million, 0.12 million more than the preceding year, with an increase of 9.50 percent. As for short-cycle and normal programs of adult education, there were 2.01 million entrants, 5.41 million enrollments and 1.94 million graduates. A total of 10.42 million people participated in self-study examinations of higher education and 0.63 million obtained certificates.19 At the same time, some people enrolled in normal and short-cycle courses provided by web-based programs or registered Viewers/auditors of Programs Provided by RTVUs (see Table 3.6). In addition, 2.89 million people participated in non-academic higher education and 5.31 million completed courses in 2009.20

Hierarchy

In October 1951, the Government Administration Council issued the ‘Decision on the Reform of Schooling,’ which stated that universities, colleges and short-cycle colleges were HEIs, that post-graduate schools would be set up at and that post-graduate education would be provided by universities and colleges. Hence, a hierarchical higher education structure was set up with short-cycle programs, undergraduate programs (normal courses programs) and post-graduate programs.

By 1965, a hierarchical structure of higher education had initially been set up, the development of which, however, was uneven, with undergraduate education as the dominant status and very low proportions of short-cycle and graduate education. In 1978, total enrollments of the three levels of HEIs were 123,712 (lowest), 266,351 and 10,708 (highest), accounting for 30.9 percent, 66.5 percent and 2.67 percent respectively.21 At the beginning of the reform and opening up, the scale of undergraduate education grew rapidly, while the enrollment of short-cycle colleges almost remained unchanged due to its importance being underestimated. From 1979 to 1982, annual entrants of short-cycle students were only 60 percent of those of 1978. In order to improve the educational structure, the State Department and the SEDC decided to increase short-cycle education in 1983. The 1985 ‘Decision’ further stated that ‘China should change the irrational hierarchical proportion of higher education, focusing on accelerating the development of short-cycle higher education.’ Judging from the percentage of each level of higher education in the 1980s, it could be seen that post-graduate education developed fast, short-cycle higher education was unstable and undergraduate education had always been at a dominant position (see Table 3.7).

Table 3.7

Number and percentage of students of different levels at regular HEIs

Source: Data for 1979 to 2005 are from Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 111–112. Data for 2009 are from the MOE.

China’s first vocational college – Nanjing Jinling Vocational College – was established in 1980, which signified the beginning of China’s vocational education. But as opposed to the rapid development of secondary vocational education, the development of higher vocational education was slow. Since the 1990s, short-cycle higher education has been developing fast. The ‘Action Plan for Vitalizing Education for the 21st Century’ issued in 1999 put forward the idea of actively developing higher vocational education. Higher vocational education has been booming since 1999, gradually becoming the main form of short-cycle higher education. And most short-cycle colleges have become places for the implementation of higher vocational education. At the Fourth National Vocational Education Conference held by the State Council in July 2002, it was decided to vigorously promote the reform and development of higher vocational education, and the vocational education system with Chinese characteristics was shaped.

With the passing of ‘Degree Regulations’ issued in 1980, graduate education in China began to move toward standardization and modernization. From 1978 to 1984, the order of higher education was restored and education grew gradually, with the total enrollment of students increasing from 0.56 million in 1976 to 1.38 million in 1978. Postgraduate education developed rapidly, with an annual growth of up to 37.1 percent, 43.8 percent and 54.9 percent respectively from 1982 to 1984.22 The scales of short-cycle and normal undergraduate education were basically stable between 1985 and 1992 and developed rapidly from 1992 to 1998, during which the development of graduate education was unsteady, with a great increase of 51.6 percent in 1985 and decreases from 1988 to 1991. Normal and short-cycle higher education in China grew steadily and graduate education developed rapidly in the 1990s. As for the proportion of students at all levels, the percentages of graduate and short-cycle students have increased since 2000. At present, short-cycle, normal and postgraduate students account for about 40 percent, 55 percent and 5 percent respectively, indicating an effective restructuring of higher education in China.

Table 3.8

Number of specialties and number of educational programs established by field of study in regular higher educational institutions in 2009

Notes: No. = Number; Sp. = specialty; Ed. Prog. = educational program.

Source: MOE.

All in all, during the last 30 years, short-cycle, normal and postgraduate education have obtained great achievements and the unevenness between these three levels of education fundamentally changed. Until now, a new and reasonable pattern of mutual promotion and coordinated development between these three levels has been set up. Such a structure is in favor of supplying talents at all levels to meet the need of China’s economic construction and social development.

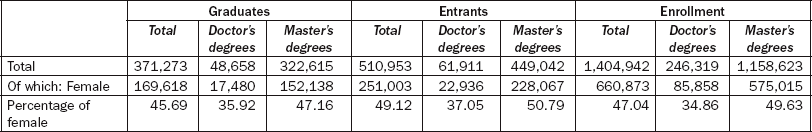

In 2009, there were 510,953 postgraduate entrants (see Table 3.10), including 61,911 doctoral candidates and 449,042 master candidates, a total increase of 64,531, namely 14.46 percent, compared with the preceding year; total enrollment of postgraduate education was 1,404,942, including 246,319 doctoral candidates and 1,158,623 master candidates, with a total increase of 116,896, namely 9.11 percent compared with the preceding year. There were 371,273 graduates, including 48,658 doctoral, and 322,615 masters, with a total increase of 26,448, namely 7.67 percent.23

Disciplines

Disciplines and specialties of higher education should always be adapted to the economic, technological and social development so as to promote the rapid development of the latter. Thus continual readjustment of the discipline structure is necessary. In 1952, China adjusted schools and departments and set disciplines in accordance with the ‘Soviet model.’ With the establishment of many single-disciplinary colleges, talented students became trained based on disciplines; in this way the discipline structure of Chinese higher education was initially formed. The ‘Discipline Catalog of HEIs’ enacted in 1954 established 11 departments and 257 disciplines. In the following years, the number of disciplines increased rapidly and then decreased with the passing of the ‘General Catalog of Undergraduate Fields of Study in HEIs’ in 1963, but the imbalance between the development of different disciplines continued to exist, with importance being attached to engineering and political sciences, law, finance and economics being ignored. Moreover, the discipline structure of higher education was ruined during the ‘Cultural Revolution.’

Table 3.9

Number of college students by field of study in 2009

Note: Students of receiving both regular and adult higher education are included.

Source: MOE.

Although higher education began to be restored in 1978, the structure of disciplines was still irrational. In 1980, there were 1,039 disciplines in HEIs, but the problems of confusion and imbalance remained prominent. Classification of disciplines was so detailed that graduates struggled to adopt. It became an urgent task to reduce the number of disciplines and broaden each discipline.

The MOE began to organize the second revision of undergraduate course catalogs, which was completed in 1987. The 1985 ‘Decision’ made it clear that ‘the structure of higher education should be adjusted and reformed according to economic construction, social development and technological progress.’ The revised catalog reduced the number of disciplines from 1,343 to 671. This revision fundamentally solved the chaos in disciplines, with scientific and standardized names, broadened coverage, and new and cross-disciplinary courses. It also restored and strengthened liberal arts, finance and economics, political sciences, and law.

In practice, China began to expand the autonomy of the HEIs from 1985, so colleges and universities began to adjust discipline and hierarchy structures – for instance, attention was paid to applied sciences, and finance, political sciences and law were strengthened – to meet the need of economic, social and technological development.

The SEDC embarked on the third revision of the Catalog of Undergraduate Fields of Study in HEIs in 1989, which was formally promulgated in 1993. With more standard names and broader coverage, a relatively complete, scientific, rational, uniform and normative undergraduate course catalog was formed. This catalog covered 10 categories of disciplines (level I), including philosophy, economics, law, education, literature, history, science, engineering, agriculture, and medicine. Under level I, there were 71 specialties (level II), under which there was a total of 504 programs.

The SEDC has conducted its fourth revision since 1997, and the new catalog was officially promulgated in July 1998, which included administration as a new discipline. There were still 71 specialties at level II, below which there were only 249 programs.

Gender and regional structure

China is a large developing country, with its social system in transformation at present. Both the society and economy are undergoing rapid development, and culture is changing as well. As a result, great change in gender and regional structure of higher education follows.

Gender difference and gender structure of higher education

Gender differences in education persist with, in general, the educational level of males higher than that of females, but the gap in higher education has been reducing in the last three decades. Female college students in China accounted for only 23.4 percent in 1980; the proportion rose to 41 percent in 2000 and was more than half (50.48 percent) in 2009 (see Table 3.11).

Generally speaking, women have obtained equal access to higher education with men. One of the main reasons is that the traditional patriarchal ideology is changing with the economic and social development of China. The second reason lies in China’s family planning policy – since most couples have only one child, whether boy or girl, they will try every means to support him/her to pursue his/her further study.

At the same time, it should be noticed that a gender gap still exists in China. It can be seen from Table 3.11 that, as for regular higher education, female students occupied 48.89 percent of the total enrollment of normal courses and 52.42 percent of total enrollment of short-cycle courses in 2009. That is to say, more women were enrolled in short-cycle courses and more men in normal courses, though the gap was narrow. Table 3.11 also shows that more women were receiving adult education and fewer were attending web-based programs. As for postgraduate education, there were fewer women students, especially for doctor’s degrees, who only occupied 34.86 percent of the total enrollment in 2009 (see Table 3.12).

It can be seen that, generally speaking, the gender structure of higher education has become more rational, which shows that discrimination against women has decreased as far as education is concerned. This is the achievement of the development of economy, society, culture, and education.

Regional structure

Regional distribution of higher education in a country or region is affected by many factors, including economic, political, historical, cultural, ethnic, and geographical factors and the law of development of the higher education system. The layout of higher education in a country is influenced by the long-term effects of these factors. China’s vast territory, large population and great gap between economies of the different regions in addition to the effect of higher education policies at different times make regional imbalance a major problem in the development of education.

When the PRC was established in 1949, the 205 HEIs in China were mainly located in the Eastern Area, of which 37 were in Shanghai. After several years of adjustment, higher education at Middle and Western Areas developed rapidly, balancing the layout to a great extent. The Great Leap Forward that started in 1958 prompted the HEIs to increase and many provinces established their own higher education system. After several years of ‘readjustment, consolidation, enrichment and improvement,’ the number of HEIs was reduced to 434 in 1965, which were mainly located in Beijing, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Hubei, and Sichuan.24

The uneven regional development in higher education still existed after the reform and opening up, which emphasized not only the imbalance between the Eastern, Middle, and Western Areas, but also the imbalance between different provinces. This affected not only the difference in the number of HEIs and students, but also the imbalance between the development of higher education and of population and economy and the uneven distribution of resources and quality of education.

The Eastern Area with a relatively developed economy has not only more HEIs and students but also better educational resources and higher quality of teaching. The inequality in regional development is mainly reflected in the difference between quality and level of education.

China encourages the balanced development of higher education across regions. In December 1986, the State Council issued ‘Interim Regulations on Setting up of HEIs,’ which stated that the SEDC should plan the overall layout of HEIs according to the goals of personnel training of HEIs, regional distribution of recruitment and graduates, and the distribution of the existing HEIs. More HEIs should be set up in the provinces and autonomous regions where higher education is lagging behind.

Table 3.13 shows that higher education in Eastern, Middle and Western Areas has undergone tremendous development, but the numbers indicate that the regional structure of higher education has not been greatly improved, with 45 percent of HEIs located in the economically developed Eastern Area, 31 percent in the Middle Area, and only about 24 percent in the vast Western Area.25 College students reflected a similar regional distribution. Higher education in East China has been the most developed and West China the most disadvantaged.

Table 3.13

Development of higher education at different regions during 1980–2005

Source: Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 125.

Regional differences in the distribution of HEIs lead to the different opportunities of receiving higher education of high school students in different regions. In regions with more HEIs, students with local Hukou (family registration system) have more opportunities to further their education at HEIs, while many students from less developed regions are deprived of their opportunities, which is also shown by the number of students per 10,000 inhabitants as reflected in Table 3.13.

Affected by many factors, quality of higher education is difficult to measure. This book chooses regional distribution of HEIs supported by the state (the ‘211 Project’ and ‘985 Project’) as an indicator. As is shown in Table 3.14, the distribution of the HEIs, two projects is quite uneven, which has a definite effect on the regional balance of China’s higher education.

Table 3.14

Regional layout of ‘211 Project’ and ‘985 Project’ HEIs

Note: Branches of universities and the twin universities at different places are all included as different HEIs. Refer to appendix.

Source: http://www.baidu.com/. Compared with the document of MOE, documents at Baidu are updated.

Since the MOE launched the ‘Plan for Counterpart Supporting Higher Education in the Western Area’ in 2001, great progress has been made in higher education in the supporting work, which promoted the development of higher education in the Western Area and educational equity, and increased the teaching level and ability to serve the local economy of HEIs in this area. The state also directly favors higher education in the West; for example, Ningxia University, Qinghai University and Tibet University were included in the ‘211 Project’ in recent years. But so far, the regional differences of higher education have not been changed significantly.

1The State Council. Suggestions on Implementing ‘Outlines of Educational Reform and Development’. MOE, 1994-7-3.

2Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 106–107.

3MOE. Educational Statistics Data, 2008, 2009.

4Wei, Yitong. Study on Private Higher Education. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, 1991: 72.

5China Daily 1992-8-7 and 1992-8-12. See Ying, Wangjiang, Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008, Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 55.

6Up to 25 March 2010, there were still 322 independent institutions. See the MOE.

7MOE.

8MOE.

9MOE.

10MOE.

11Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 51.

12Min, Weifang. Study on the Operating Mechanism for Higher Education Beijing: People’s Education Press: 653.

13Gu, Jianmin, Xueping Li and Lihua Wang. Higher Education in China. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University Press, 2009: 29.

15Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 72–74.

16Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 75.

17China Scholarship Council. List of government-sponsored postgraduates going abroad for academic pursuits in 2010. http://www.csc.edu.cn.

18MOE.

19MOE.

20MOE.

21Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 109.

22Ying, Wangjiang. Reform and Development of Higher Education in China: 1978–2008. Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2008: 94.

23MOE.

24Department of Finance and Planning of MOE. Educational Achievement of China (1949–1983). Beijing: People’s Education Press, 1984: 254–257.

25Eastern Area includes Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong and Hainan municipalities and provinces, with 41.2 percent of the total population and 13.5 percent of the total area of China.

Middle Area includes Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei and Hunan provinces, with 35 percent of the total population and 29.3 percent of the total area of China.

Western Area includes Inner Magalia, Guangxi, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia and Xinjiang provinces and autonomous regions and Chongqing municipality, with 23 percent of the total population and 56.4 percent of the total area of China.