13

Writing the Incident Report

An incident response team functions in the same way that a fire department does. Both teams take time to prepare themselves with training on their respective techniques, tools, and practices, and they can respond at a moment’s notice to a fire or an incident. During their response to a fire, the firefighters take notes and record their actions, ensuring that critical decisions are documented and that individual contributions are noted. Once the fire is out, they sift through the debris to determine the causes and origins of the fire. Once the proper documentation has been prepared, the fire department conducts an after-action review to critique their performance and find avenues for improvement. Other reports allow fire departments and safety experts to update building codes and improve the survivability of structures should a fire break out.

Incident response teams utilize much of the same workflow. During an incident, notes are taken and actions are recorded. Evidence is obtained from systems and maintained in a forensically sound manner. A root cause analysis is conducted utilizing the notes, observations, and evidence obtained during the incident. This root cause analysis is utilized by information technology personnel to patch up vulnerabilities and further harden systems. Finally, the team conducts its own after-action review where the series of events is laid out and critiqued so that the team may improve their processes, their tools, and their techniques as well as make any corrections to the incident response plan.

To maximize the benefits of the root cause analysis and after-action brief, incident responders will need to ensure that all their actions are recorded in a proper fashion. They will also be required to prepare several documents that senior leaders and decision-makers will use when considering the future state of the IT infrastructure.

To better prepare responders to craft the necessary documentation, the following topics will be addressed:

- Documentation overview

- Executive summary

- Incident investigation report

- Forensic report

- Preparing the incident and forensic report

Documentation overview

This will be an overview of incident documentation. In this section, we will look at what data to capture, the different audiences, and how to properly source the report content.

The documentation associated with an incident takes several forms. The length of any documentation is often dictated by the type of incident. Simple incidents that take very little time to investigate and have a limited impact may be documented informally in an existing ticketing system. However, in more complex incident investigations, such as a data breach that has led to the disclosure of confidential information (such as medical records or credit card information), you may require extensive written reports and supporting evidence.

What to document

When looking at documenting an incident, it is not very difficult to ascertain what should be documented. Following the five Ws (Who, What, Where, When, and Why), and sometimes How, is an excellent foundation when considering what to document during an incident. Another good piece of wisdom when discussing documentation, especially when discussing the legal implications of security incidents, is the axiom that if you didn’t write it down, it didn’t happen. This statement is used to drive home the point that proper documentation is often comprised of as much detail as the incident response analyst can provide. Analysts may be involved in an incident that ends up in a civil proceeding. The wheels of justice often move slowly, and an analyst may be called to the witness stand after 18 months, during which 10 other incidents may have transpired. Having as much detail available in the incident reporting will allow analysts to be able to reconstruct the events in a proper manner.

An excellent example of using these five Ws (and one H) structure in your documentation is when looking at a digital forensics task, such as imaging a hard drive. In Chapter 8, proper documentation was partially addressed when we looked at the practice of imaging the suspect drive. The following is a more detailed record of the event:

- Who: This is the easiest detail to note. Simply, who was involved in the process? For example, the person involved was analyst Jane Smith.

- When: Record the date and time that the imaging began and when it ended. For example, the imaging process started at 21:08 UTC on June 16, 2022, and ended at 22:15 UTC on June 16, 2022. Time is critical, and you should ensure that a normalized time zone is utilized throughout the investigation and indicated in the report.

- Where: This should be a detailed location, such as an office.

- What: The action that was performed; for example, acquiring memory or firewall logs or imaging a drive.

- Why: Having a justification for the action helps in understanding the reason why the action was performed.

- How: A description of how an action is performed should be included. Additionally, if an incident response team utilizes playbooks or standard operating procedures as part of their plan, this should be included. Any departure from the standard operating procedures should also be similarly recorded.

Putting all this information together, the following sample language can be entered into the report:

On June 16, 2022, analyst Jane Smith arrived at office 217 of the Corporate Office Park located at 123 Maple St., Anytown, US, as part of the investigation. Upon arrival, Smith took control of the Dell laptop, asset tag #AccLT009, serial #7895693-862. An alert from the firewall IDS/OPS indicated that the laptop had communicated with a known Command and Control server. The laptop was to be imaged in an attempt to ascertain whether it had been infected with malware. At 21:08 UTC, Smith imaged the drive utilizing the live imaging technique in accordance with the Standard Operating Procedure IR-002. The process was completed at 22:15 UTC on June 16, 2022.

This entry provides sufficient detail to reconstruct the events that transpired. Taken together with other documentation, such as photographs and chain of custody, the analyst has a clear picture of the process and the outcome.

Types of documentation

There is no one standard that dictates how an incident is documented, but there are a few distinct categories. As previously stated, the depth of the documentation will often depend on the type, scale, and scope of an incident; however, in general, the following categories apply:

- Trouble ticketing system: Most enterprise organizations have an existing ticketing system utilized to track system outages and other problems that normally arise in today’s network infrastructure. These systems capture a good deal of data associated with an incident. An entry usually captures the start and stop date and time, the original reporting person, and the action performed, and also provides an area for notes. The one major drawback to ticketing systems is that they were originally designed to support the general operations of enterprise infrastructures. As a result, more complex incidents will require much more documentation than is possible in these systems. Due to this, they are often reserved for minor incidents, such as isolated malware infections or other such minor incidents that are disposed of quickly.

- Security Orchestration and Automation (SOAR) platforms: Some organizations have seen the need for a dedicated incident response platform and have come up with applications and other types of infrastructure that support incident response teams. These incident response orchestration platforms allow analysts to input data, attach evidence files, and collaborate with other team members as well as pull in outside resources, such as malware reverse engineering and threat intelligence feeds.

There are several of these platforms available both commercially and as freeware. The main advantage of these platforms is that they automate the capture of information, such as the date, time, and analyst’s actions.

Another distinct advantage is that they can limit who is able to see the information to a select group. With ticketing systems, there is the possibility that someone without authorization will observe details that the organization may want to keep confidential. Having an orchestration system can provide a certain level of confidentiality. Another key advantage is the ability for team members to see what actions are taken and what information is obtained. This cuts down the number of calls made and the possibility of miscommunication.

- Written reports: Even with automated platforms in use, some incidents require extensive written reporting. In general, these written reports can be divided into three main types. Each of the following types will be expanded on later in this chapter:

- Executive summary: The executive summary is a one- to two-page report that is meant to outline the high-level bullet points of the incident for the senior management. A brief synopsis of the events, a root cause, if it can be determined, and remediation recommendations are often sufficient for this list.

- Incident investigation report: This is the detailed report that is seen by a variety of individuals within the organization. This report includes the details of the investigation, a detailed root cause analysis, and thorough recommendations on preventing the incident from occurring again.

- Forensic report: The most detailed report that is created is the technical report. This report is generated when a forensic examination is conducted against the log files, captured memory, or disk images. These reports can be very technical, as they are often reviewed by other forensic personnel. These reports can be lengthy as outputs from tools and portions of evidence, such as log files, are often included.

Understanding the various categories that comprise an incident report allows responders to properly organize their material. Even smaller incidents create documentation, meaning that responders can become overwhelmed. Coupled with the high number of data sources, the reporting process can become a chore. To make the process flow better, responders should be prepared to address the various categories at the onset of an incident and organize their documentation accordingly.

Sources

When preparing reports, there are several sources of data that are included within the documentation, whether the incident is small, requiring only a single entry into a ticketing system, all the way to a complex data breach that requires extensive incident and forensic reporting. Some sources include the following:

- Personal observations: Users may have some information that is pertinent to the case. For example, they might have clicked on a file in an email that appeared to come from a legitimate address. Other times, analysts may observe behavior in a system and make a note of it.

- Applications: Some applications produce log files or other data that may be necessary to include in a report.

- Network/host devices: A great deal of this book deals with acquiring and analyzing evidence from a host of systems in an enterprise environment. Many of these systems also allow outputting reports that can be included with the overall incident or forensic reporting.

- Forensic tools: Forensic tools often have automated reporting functions. This can be as simple as an overview of some of the actions, as was addressed in the previous chapters, or the actual outputs, such as file hashes, that can be included within a forensic report.

Wherever the material comes from, a good rule to follow is to capture and include as much as possible in the report. It is better to have more information than less.

Audience

One final consideration to bear in mind when preparing your documentation is who will read an incident report versus a detailed forensic report. In general, the following are some of the personnel, both internal and external to an organization, that may read the reports associated with an incident:

- Executives: High-profile incidents may be brought to the attention of the CEO or CFO, especially if they involve the media. The executive summary may suffice, but do not be surprised if the senior leadership requires a more detailed report and briefing during and at the conclusion of an incident.

- Information technology personnel: These individuals may be the most interested in what the incident response analysts have found. Most likely, they will review the root cause analysis and remediation recommendations very seriously.

- Legal: If a lawsuit or other legal action is anticipated, the legal department will examine the incident report to determine whether there are any gaps in security or the relevant procedures for clarification. Do not be surprised if revisions must be made.

- Marketing: Marketing may need to review either the executive summary or the incident report to craft a message to customers in the event of an external data breach.

- Regulators: In regulated industries, such as healthcare and financial institutions, regulators will often review an incident report to determine whether there is a potential liability on the part of the organization. Fines may be assessed based upon the number of confidential records that have been breached, or if it appears that the organization was negligent.

- Cyber insurers: Cyber insurance is a recent development, largely in response to the explosion in ransomware. Cyber insurance companies may want to examine any written reports by analysts or responders in conjunction with claims filed by their customers.

- Law enforcement: Some incidents require law enforcement to become involved. In other instances, law enforcement may want to capture any IOCs or other data points associated with the investigation as it may help with potential future incidents. In these cases, law enforcement agencies may require copies of incident and forensics reports for review.

- Outside support: There are instances where an outside forensics or incident response support firm becomes necessary. In these cases, the existing reports would go a long way in bringing these individuals up to speed.

Understanding the audience gives incident response analysts an idea of who will be reading their reports. Understand that the report needs to be clear and concise. In addition to this, technical details may require some clarification for those in the audience that do not have the requisite knowledge or experience.

Executive summary

Executives need to know key details of an incident without all the technical or investigative material. This section will examine how to prepare an effective executive summary that captures the needed details and recommendations for executives and other key stakeholders.

As was previously discussed, the executive summary captures the macro-level view of the incident. This includes a summary of the events, a description of the root cause, and what recommendations are being made to remediate and prevent such an occurrence from happening again. In regulated industries, such as financial institutions or hospitals that have mandatory reporting requirements, it is good practice to state whether the notification was necessary, and, if it was necessary, how many confidential records were exposed. This allows senior management to understand the depth of the incident and ensure that the appropriate legal and customer communication steps are addressed.

The name of this report can be a bit misleading. The assumption is that this report is only for C-suite executives. While that is one of the target audiences, there are others that will often ask to be read in on an executive summary. Legal and marketing may need to have at least a cursory overview of the pertinent facts so that communications to customers or third parties can be accurately crafted. Other such external regulators may need a summary of the incident before a complete incident and technical analysis report has been crafted.

Let’s expand on the previous discussion on what the executive summary should contain. There is no hard and fast rule when it comes to content, but the following is a good foundation for the summary:

- Summary of the events: This is a brief, maybe half-page summary of the key events that took place during the incident. It is not meant to be a complete hour-by-hour account, but rather the key events that took place such as the initial detection, when the incident was contained, when the threat was completely removed from the environment, and, finally, when operations were back up and running.

- Graphic timeline: A graphic timeline helps in placing the key events on the appropriate day and time. Keep this graphic to about 8-12 specific entries that capture the high-level events.

- Root cause overview: The root cause of the incident will be captured in the incident investigation report, but a short summary is helpful to the executive level to understand the nature of the incident. This can be a short statement, a few sentences, or a paragraph. For example, the following is sufficient for a root cause statement:

The incident investigation determined that a still unknown adversary exploited a vulnerable web server using a specially crafted exploit. From here, the adversary was able to pivot into the enterprise network due to a network misconfiguration and execute ransomware on systems.

- High-level recommendations: A table with strategic and tactical recommendations should be included with a tie to the incident investigation report.

- Additional reporting: A brief statement concerning any additional documentation that will be prepared. For example, the author may want to include a statement indicating that the incident and associated forensics reports are being prepared and should be available within two weeks. This lets the readers know that if they need additional context or details, that is forthcoming.

From a workflow perspective, the executive summary can often be crafted as the first written documentation concerning the incident. For example, a major incident that takes two weeks to analyze and remediate will produce extensive documentation. An executive summary can be leveraged as a stop-gap measure for the time it takes to prepare the full report. This allows the leadership and other stakeholders to craft messaging, make immediate changes to the environment, and make other decisions without having to wait.

There are a few guidelines to follow when preparing an executive summary. First, keep the language at a high level of simplicity. Specific technical terms may confuse some readers so keep the language as non-technical as possible. Second, keep it short with an opening to follow on documentation. Third, keep the discussion high level with a focus on a macro level impact on the organization. Two pages are usually the maximum. In certain circumstances, it may be beneficial to use a PowerPoint presentation in place of a written summary.

Incident investigation report

A comprehensive incident investigation involves a wide variety of actions performed by various personnel. These actions are captured in the narrative report that details the sequence of the investigation along with providing a timeline of events.

The incident report has perhaps the widest audience within, and external to, the organization. Even though there are individuals with limited technical skills who will be reviewing this report, it is important to have the proper terminology and associated data. There will always be time to explain technical details to those that may be confused.

The following are some of the key pieces of data that should be captured and incorporated into the report:

- Background: The background is the overview of the incident from detection to final disposition. A background of the incident should include how the CSIRT first became aware of the incident and what initial information was made available. Next, it should draw conclusions about the type and extent of the incident. The report should also include the impact on systems and what confidential information may have been compromised. Finally, it should include an overview of what containment strategy was utilized and how the systems were brought back to normal operation.

- Events timeline: As the report moves from the background section to the events timeline, there is an increased focus on detail. The events timeline is best configured in a table format. For each action performed, an entry should be made in the timeline. The following table shows the level of detail that should be included:

|

Date |

Time (UTC) |

Description |

Performed by |

|

6/17/22 |

19:08 |

Firewall IPS sensor alerted to possible C2 activity. Escalated by the SOC to the CSIRT for analysis and response. |

Bryan Davis |

|

6/17/22 |

19:10 |

Examined firewall log and determined that host 10.25.4.5 had connected to a known malware C2 server. |

John Q. Examiner |

|

6/17/22 |

19:14 |

Used Carbon Black EDR to isolate the endpoint 10.25.4.5 from further network communication. |

John Q. Examiner |

|

6/17/22 |

19:16 |

Retrieved Prefetch files from 10.25.4.5 via Velociraptor for analysis. |

John Q. Examiner |

Table 13.1 – Events timeline log

A key facet of the timeline to keep in mind is that entries will be put in place before those that indicate actions by the CSIRT. In the previous table, the Prefetch files will be analyzed with the intent of showing the execution of malware. These entries will obviously predate the CSIRT activity.

This log may include several pages of entries, but it is critical to understand the sequence of events and how long it took to perform certain actions. This information can be utilized to recreate the sequence of events, but it can also be utilized to improve the incident response process by examining response and process times.

- Network infrastructure overview: If an incident has occurred that involves multiple systems across a network, it is good practice to include both a network diagram of the impacted systems and an overview of how systems are connected and how they communicate with each other. Other information, such as firewall rules that have a direct bearing on the incident, should also be included.

- Forensic analysis overview: Incidents that include the forensic analysis of logs, memory, or disk drives, an overview of the process, and the results should be included in the incident report. This allows stakeholders to understand what types of analyses were performed, as well as the results of that analysis, without having to navigate the very technical aspects of digital forensics. Analysts should ensure that conclusions reached via forensic analysis are included within this section. If the incident response team made extensive use of forensic techniques, these can be recorded in a separate report covered later in this chapter.

- Containment actions: One of the key tasks of an incident response team is to limit the amount of damage to other systems when an incident has been detected. This portion of the report will state what types of containment actions were undertaken, such as powering off a system, removing its connectivity to the network, or limiting its access to the internet. Analysts should also ensure that the effectiveness of these measures is incorporated into the report. If, for example, it was difficult to administratively remove network access via accessing the switch, and a manual process had to be undertaken, knowledge of this fact will help the CSIRT create new processes that streamline this action and limit the ability of a compromised host accessing the other portions of the network.

- Findings/root cause analysis: The meat of the report that is of most use to senior leadership and information technology personnel is the findings and, if it has been discovered, the root cause. This portion of the report should be comprehensive and incorporate elements of the timeline of events. Specific factors within hosts, software, hardware, and users that contributed to either a negative or positive outcome within the incident should be called out. If the specific exploit used by the attacker, or a vulnerability that was exploited, has been determined, then this should also be included. The overall goal of this portion of the report is to describe how the threat was able to compromise the infrastructure and lend credence to the remediation and recommendations that follow.

- Remediation: If steps were taken during the incident to remediate vulnerabilities or other deficiencies, they should be included. This allows the CSIRT to fully brief other IT personnel on the changes that were made to limit damage to the rest of the network so that they can then be placed into the normal change control procedures and vetted. This ensures that these changes do not have an adverse impact on other systems in the future.

- Final recommendations: Any recommendations for improvements to the infrastructure, patching of vulnerabilities, or additional controls should be included in this section of the report. However, any recommendations should be based upon observations and a thorough analysis of the root cause.

- Definitions: Any specific definitions that would aid technical personnel in understanding the incident should be included within the report. Technical terms, such as Server Message Block (SMB), should be included if an exploit was made against vulnerabilities within the SMB protocol on a specific system.

It is critical to understand that this report is the most likely to make its way to various entities within, and external to, the organization. The report should also make its way through at least one quality control review to make sure that it is free of errors and omissions and can be read by the target audience.

Forensic report

The examination of digital evidence produces a good deal of technical details. Observations and conclusions that are reached as part of the investigation report need to be backed up by data. A technical report captures the pertinent details concerning the analysis of digital evidence that serves as the backbone of the overall incident report.

Forensic reports are the most technically complex of the three main report types. Analysts should be free to be as technically accurate as possible and not simplify the reporting for those that may be nontechnical. Analysts should also be aware that the forensic report will be critical to the overall incident reporting if it was able to determine a specific individual, such as a malicious insider.

In cases where a perpetrator has been identified, or where the incident may incur legal ramifications, the forensic report will undergo a great deal of scrutiny. It, therefore, behooves the analyst to take great pains to complete it accurately and thoroughly, as follows:

- Examiner bio/background: For audience members such as legal or external auditors, it is critical to have an idea of the background and qualifications of the forensic analysts. This background should include formal education, training, experience, and an overview of an analyst’s courtroom experience, which should include whether they were identified as an expert witness. A complete CV can be attached to the forensic report, especially if it is anticipated that the report will be used as part of a court case.

- Tools utilized: The report should include a complete list of hardware and software tools that were utilized in the analysis of evidence. This information should include the make, model, and serial number of hardware, such as a physical write blocker, or the software name and version utilized for any software used. A further detail that can be included in the report is that all tools were up to date prior to use.

- Evidence items: A comprehensive list of the evidence items should include any disk images, memory captures, or log files that were acquired by the analysts during the incident. The date, time, location, and analyst who acquired the evidence should also be included. It may be necessary to include as an attachment the chain of custody forms for physical pieces of evidence. If there are a number of evidence items, this portion of the report can be included as an addendum to allow for a better flow of reading for the reader.

- Forensic analysis: This is where analysts will be very specific with the actions that were taken during the investigation. Details such as dates and times are critical, as well as detailed descriptions of the types of actions that were taken.

- Tool output: In the previous chapters, there have been a great many tools that have been leveraged for investigating an incident. Some of these tools, such as Volatility or Rekall, do not have the ability to generate reports. It is, therefore, incumbent upon the analyst to capture the output of these tools. Analysts can include screen captures or text output from these command-line tools and should incorporate them within the report. This is critical if these tools produce an output that is pertinent to the incident.

Incident report template

There is no clear and concise guidance on how to write up an incident report. While the main information is uniform, there are no specifics on how to craft a report and what it looks like. For those that are just getting started, a good template to use is one that Lenny Zelster provides at https://zeltser.com/media/docs/cyber-threat-intel-and-ir-report-template.pdf. This can provide a good starting point.

Other tools, such as Autopsy, can output reports for inclusion in the forensic analysis report. For example, to run the report from the analysis conducted in the previous chapter, perform the following steps:

- Open the case in Autopsy.

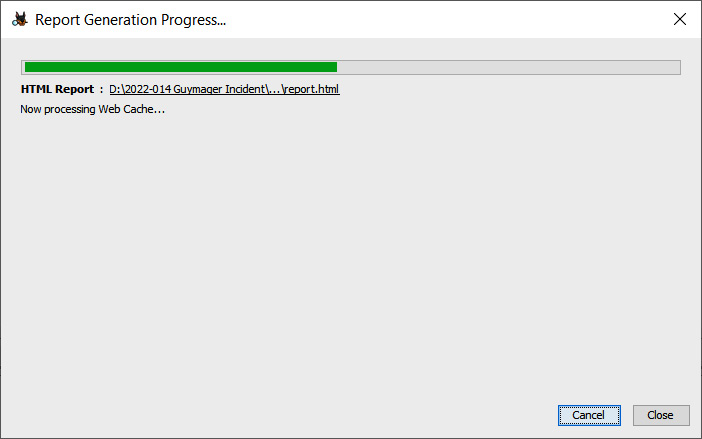

- At the top bar, click on Generate Report. This opens the following window:

Figure 13.1 – Autopsy report generation

Depending on the type of report, some information needs to be entered. In this case, an HTML Report is selected, and the Header and Footer values need to be set.

- Once the information is entered, click Next. Set the Data Source you would like to include as part of the report. In this case, we will select that Laptop1Final.E01 file that was used in Chapter 11:

Figure 13.2 – Autopsy report generation data source selection

- On the next screen, the analyst can select what types of results are to be included in the report. For example, if the analyst wants to report only on tagged results, they can select that data set. In this case, all data will be included, and then click Finish:

Figure 13.3 – Autopsy Generate Report results selection

This will start the process of outputting the analysis:

Figure 13.4 – Autopsy Report Generation Progress

Once the output has completed, it will be contained in the Reports directory for the associated case file. From here, the analyst can review the information. Other techniques, such as printing to a PDF file, allow analysts to attach the output directly to the report. Analysts should become familiar with their toolset as having the ability to export a report directly from the tool will reduce errors and can stand up better under scrutiny. The following are three important aspects of a report:

- Conclusions: Conclusions that are derived from the evidence can be included in the report. For example, if an analyst determines that a specific executable is malware by matching the hash with a known strain, and that this malware steals credentials, they are well within their bounds to make that conclusion. However, analysts should be cautious about supposition and making conclusions without the proper evidence to support them. Responders should be careful to never make assumptions or include opinions in the report.

- Definitions: As the forensic report is very technical, it is important to include the necessary definitions. Internal stakeholders, such as legal representatives, will often review the report if legal action is anticipated. They may need further clarification on some of the technical details.

- Exhibits: Output from tools that are too long to include within the body of the report can be included as an addendum. For example, if the output of a Volatility command is several pages long, but the most pertinent data is a single line; the analyst can pull that single line out and include it in the forensic analysis portion while making it clear that the entire output is located as an addendum. It is important to include the entire output of a tool as part of this report to ensure that it will stand up to scrutiny.

One of the key factors of the forensic report is to have a peer-review process before it is issued as part of the incident documentation. This is to ensure that the actions that have been performed, the analysis, and the conclusions match the evidence. This is one of the reasons that analysts should include as much data as possible from the output of tools or through the review. If a forensic report does go to court, understand that an equally or even more qualified forensic analyst may be reviewing the report and critiquing the work. Another responder or analyst should be able to review the report, review the descriptions of the responder’s work, and come to the same conclusion. Knowing this may make analysts more focused on preparing their reports.

Whether or not an organization chooses to separate the documentation or prepare a master report, there is certain data that should be captured within the report. Having an idea of what this data is comprised of allows incident response personnel to ensure that they take the proper notes and record their observations while the incident investigation is in progress. Failure to do so may mean that any actions taken, or observations made, are not captured in the report. Furthermore, if the case is going to see the inside of a courtroom, evidence may be excluded. It is better to over-document than under-document.

Preparing the incident and forensic report

The contents for reporting can come from a variety of sources and forms. Putting this all together along with preparing contemporaneous note-taking goes a long way to ensuring all the pertinent facts are captured and reported.

To round out the discussion on reporting, there are two additional subjects that impact the overall reporting process. These two topics, note-taking, and how to ensure the proper language is included in the report. Analysts should pay particular attention to these two topics as they have a direct bearing on the quality of the report and how it can be used.

Note-taking

Often overlooked, note-taking is a critical part of the analysis and reporting process. Failing to take proper notes contemporaneously with the analysis will make reconstructing the events with sufficient detail impossible or in some circumstances, analysts will need to repeat a process to capture the necessary data and artifacts.

Proper notes contain the specifics that were covered in the What to document section. For example, an analyst is conducting an examination of the Prefetch files of a suspect system. The following is a sample note entry:

At 20220617T19:13 UTC, discovered prefetch entry from system DS_453.local with prefetch parser, that indicated on 20220617T02:31 UTC, executable 7dbvghty.exe was run from the C: directory.

The previous entry contains all the necessary data to make a detailed portion of the report. In fact, anyone else who reads the note entry would be able to reconstruct what the analyst did. The following incident or forensic report entry can be crafted using that note:

At 20220617T19:13 UTC, G. Johansen conducted an analysis of the system DS_453.local Prefetch file, utilizing Prefetch parser to determine what, if any, potentially malicious programs were executed. The analysis indicated that at 20220617T02:31 UTC, an executable with the file name 7dbvghty.exe was executed from the system C: directory.

The importance of note-taking during the investigation should not be understated. Analysts could be conducting analysis on many systems and uncovering evidence from a variety of sources. Imagine conducting a log review of 20-30 systems over the course of twelve hours. It is impossible to keep track of all the key data points and actions that took place.

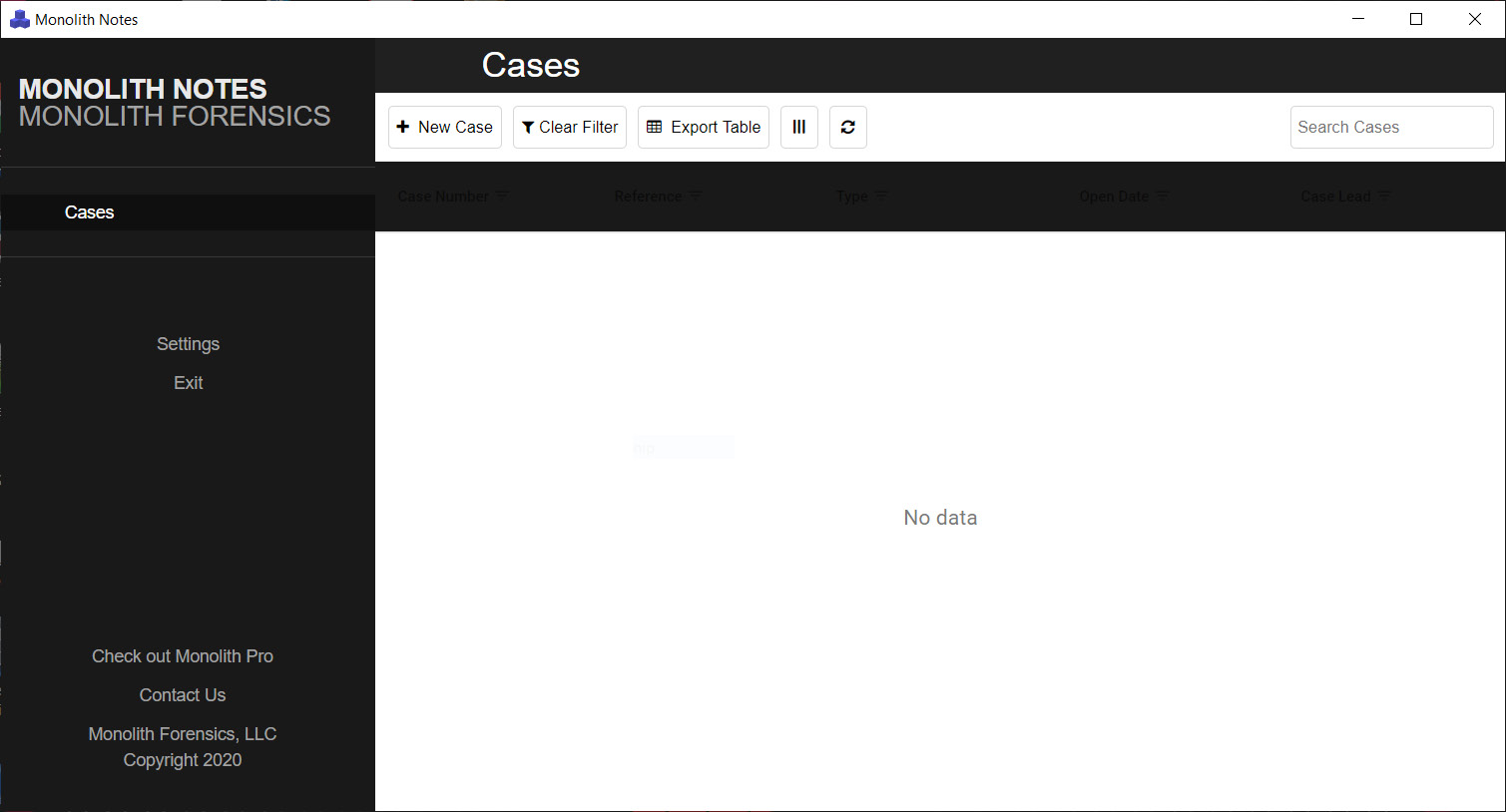

There are several options when it comes to note-taking during an incident. There are simple cloud solutions such as Google Docs that can be leveraged, with the caveat that proper security should be maintained. A simple Word document or text editor can also be used. Additionally, there are purpose-designed platforms for note-taking. In this case, we will look at Monolith Forensics’ Monolith Notes. This application can be run locally on an analysis machine, or if a team needs to have a collaborative environment, there is a professional version that can be deployed either in a cloud environment or on-premises. In this case, we will look at the open source version of the tool available at https://monolithforensics.com/case-notes/.

The download has a simple setup for the Windows or macOS operating systems. Download the file and execute it. Once installed, open the application and the following screen will appear:

Figure 13.5 – Monolith Notes’ main screen

As an example, we are going to go ahead and use the application to aggregate notes along with showing how they can be exported:

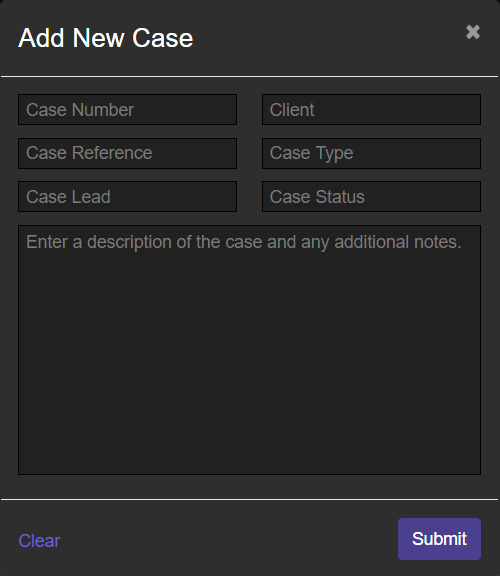

- Click on New Case and the following window will open:

Figure 13.6 – New Case information

- Enter the pertinent details concerning the case. Monolith Notes can handle multiple cases at a time. In this instance, the following information is entered, and once completed, click the Submit button:

Figure 13.7 – New Case information

- To add a note from the main screen, click the Add Note button, which opens the following free text field:

Figure 13.8 – Free text note field

- On the preceding screen, the analyst can add free text notes along with screen captures. In this case, a screen capture of the Prefetch entries of a suspect laptop is entered with a short note. After completing, click Submit and the note is captured:

Figure 13.9 – Completed note

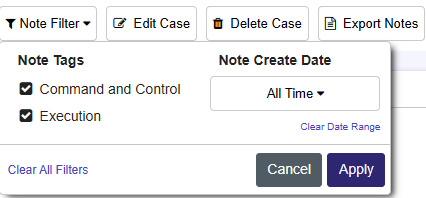

One handy feature that is included with Monolith Notes is the ability to apply specific tags to each note entry. For example, in the previous screenshot, the tag applied was Execution, which is related to a technique of the MITRE ATT&CK framework (the MITRE ATT&CK framework will be discussed in detail in Chapter 15). The tags can be applied when adding a new note. The advantage to this tagging is when the analyst needs to go back and look at all evidence items associated with the execution of an application:

Figure 13.10 – Monolith Notes filter

Finally, Monolith Notes can export the notes into a Microsoft Word document. This makes it much easier to move screen captures around as well as cut and paste specific data such as timestamps, code blocks, or other tool outputs.

Report language

To round out the discussion on reporting, it is important to specifically address how to structure the language of the reporting, specifically the forensic report. The executive summary and incident reports will often use a narrative tone. Specifically, outlining the steps and sequence of events that took place over the course of the incident. It is only really the root cause analysis that will proffer a conclusion based on the evidence.

Technical report statements can be divided into three categories that describe how the data and ultimately the conclusions are presented:

- Technical statements: This is an objective description of the findings related to a specific data point. For example, a technical statement concerning the location of malicious code execution in the Prefetch file would look like the following: A Prefetch entry for the executable sample.exe was found within the system’s C:WindowsPrefetch directory.

- Investigative statements: In this case, the analyst is expressing possible meanings or outcomes related to the specific data point. In this case, the previous statement about the Prefetch entry will be expanded on as follows: A Prefetch entry for the executable sample.exe was found within the system’s C:WindowsPrefetch directory. Entries in the Prefetch directory indicate that an executable was executed.

- Evaluative statement: In the previous two examples, there was a lack of any evaluation concerning the evidence or the likelihood of an event. In an evaluative statement, the analysts are expressing their opinion concerning the strength of the evidence indicative of the likelihood of an event. In this case, the statement concerning the Prefetch entry will look like the following: A Prefetch entry for the executable sample.exe was found within the system’s C:WindowsPrefetch directory. Entries in the Prefetch directory indicate that an executable was executed. This indicates that there is a high degree of certainty that at 20220617T1913 UTC, the file sample.exe was executed.

In addition to the language that is used, the analysts should ensure that they follow some additional guidelines when preparing the report:

- Conclusions with data: It is fine for an analyst to have conclusions as we saw in crafting evaluative statements. This must be backed up with data. Any conclusion reached during the analysis and subsequent reporting needs to have firm data to back it up.

- Don’t guess: It is fine for an analyst to provide an expert-based opinion on a scenario that most likely happened if it is backed up by data. If evidence is missing, which does occur often, be honest and indicate that in the report. For example, an analyst may be investigating a ransomware incident and lack specific visibility into lateral movement techniques. They may indicate that they know from an analysis of ransomware threat actors that they utilize tools such as PSEXEC.exe or Remote Desktop Protocol along with compromised credentials, but due to the lack of logging, they are unable to determine the exact method of lateral movement.

- Repeatability: A comprehensive and well-written technical report should be one where, given the same evidence, an analyst with no prior knowledge of the incident should be able to reconstruct your findings. This is especially true for law enforcement or analysts that may have to testify as the report and associated evidence will be provided to the other party.

The language used in the report is often just as important as all the analysis work that goes into it. A poorly written report with bad conclusions and improper language can have a negative impression on the readers. In cases where the evidence will be included as part of a civil or criminal proceeding, it is likely that all the work put in cannot be admitted. Analysts should develop good note-taking and writing along with their technical skills.

Summary

Incident response teams put a great deal of effort into preparing for and executing the tasks necessary to properly handle an incident. Of equal importance is properly documenting the incident so that decision-makers and the incident response team itself have a clear understanding of the actions taken and how the incident occurred. It is by using this documentation and analyzing a root cause that organizations can improve their security and reduce the risk of similar events taking place in the future. One area of major concern to incident responders and forensic analysts is the role that malware plays in incidents.

Questions

Answer the following to test your knowledge of this chapter:

- What is not part of a forensic report?

- The tools utilized

- Examiner biography / CV

- Notes

- Exhibit list

- When preparing an incident report, it is necessary to take into account the audience that will read it.

- True

- False

- Which of these is a data source that can be leveraged in preparing an incident report?

- Applications

- Network/host devices

- Forensic tools

- All of the above

- Incident responders should never include a root cause analysis as part of the incident report.

- True

- False

Further reading

Refer to the following for more information about the topics covered in this chapter:

- Intro to Report Writing for Digital Forensics: https://digital-forensics.sans.org/blog/2010/08/25/intro-report-writing-digital-forensics/

- Understanding a Digital Forensics Report: http://www.legalexecutiveinstitute.com/understanding-digital-forensics-report/

- Digital Forensics Report, Ryan Nye: http://rnyte-cyber.com/uploads/9/8/5/9/ 98595764/exampledigiforensicsrprt_by_ryan_nye.pdf

- Magnet Forensics Guide on Technical Level Findings: https://www.magnetforensics.com/resources/reporting-findings-at-a-technical-level-in-digital-forensics-a-guide-to-reporting/