6

Make 1+1=11

Creating Partnerships with Synergies and Multiplier Effects

If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

—African proverb

In an emergency, when people need to get pails of water to a fire or sandbags to stop a flood, they may create “bucket brigades,” lines of people passing heavy items. It’s much faster than everyone hauling a single bucket, and it’s a classic example of partnership yielding nonlinear returns. Our shorthand for the multiplier effects from collaboration is “one plus one equals eleven.”

To fight the battle against our environmental and social challenges, we need the rapid expansion of productivity that comes from partnership. No company can make a serious dent in the problems that a whole industry, or the world, faces. Only together can a sector or region shift the standard practices or cost structure of, for example, building efficiency technologies, renewable energy, or sustainable palm oil. Some of a net positive company’s goals will be impossible to reach without help. Making facilities zero waste, for instance, could be difficult for some materials. You may get to half the solution on your own, but then need to find companies that can use the material, or value chain partners to share the burden of building recycling infrastructure.

When Unilever’s former manufacturing sustainability director, Tony Dunnage, was tasked with moving the company’s two hundred–plus factories to zero waste, his boss asked him, “What budget do you need? How many people and how many consultants?” Dunnage says he shocked his boss when he answered, “I don’t need any people or budget … what I need is partnerships.”1

Nowhere is this need for collaboration more urgent than in battling climate change. Large companies are almost all working to cut their direct and indirect (from the electric grid) carbon emissions—called Scope 1 and Scope 2 by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. But the real breakthroughs come from assuming responsibility for, and teaming up to tackle, supplier and customer emissions, called Scope 3. In most industries, Scope 3 makes up the large majority of value chain emissions.

A net positive company, because it uses a multistakeholder model, will inherently look for alliances within an ecosystem of players that share interests. This network should grow to include peers, suppliers, NGOs, and governments. It’s not just that some issues are hard to solve alone; it’s that our challenges are so intertwined, it’s impossible to work on one problem at a time. Partnerships will inevitably overlap, forcing systems thinking. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with their seventeen areas for action, are deliberately designed to interact, in systems, and reinforce one another. Without partnering, which is the seventeenth SDG, achieving the other sixteen goals will be impossible.

The SDGs are a partnership for humanity; they’re multigenerational, with purpose at the core, and aim to ensure that nobody is left behind. The companies that embrace the opportunity from meeting the SDGs—an estimated $12 trillion and 380 million jobs globally, by 2030, in only four sectors—will thrive.2 It’s the biggest business opportunity in history, waiting to be unlocked.

As someone wise once said (likely Einstein), we can’t solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them. The time for higher-level, transformative partnerships has arrived.

Two Core Types of Partnerships

This chapter and the next explore collaborations in two big categories (see table 6-1). We draw a distinction between problems that can be solved with a subset of stakeholders, and optimize results within our current system, and those that require all the players (and in particular governments) to change systems.

TABLE 6-1

Two scales of partnership

|

Chapter 6: 1+1=11 Creating Partnerships with Synergies and Multiplier Effects |

Chapter 7: It Takes Three to Tango Systems-Level Reset and Net Positive Advocacy |

|---|---|

|

Scaling with the system |

Changing the system |

|

May need competitors to get more done |

Need more players (policy, finance) |

|

Solving shared industry risk |

Building the greater common good |

|

Localized regions or supply chains |

Full systems |

|

Some civil society partners |

All participants in the system |

|

Action (More “do”) |

Action and advocacy (More “say”) |

Think of competitors working with their shared suppliers to innovate around new materials for recyclable packaging. The effort would benefit everyone in the sector. That’s the first category, and what we’re calling a 1+1=11 partnership, since it creates multiplier effects. Companies can make progress on issues like this without much government support, but it doesn’t mean only business coming together; you may need technical perspective from academia or NGOs. These partnerships often address opportunities or risks that competitors share—for example, a human rights issue in the sector’s supply chain is everyone’s problem. Broadly speaking, this kind of collaboration is focused on action to scale up solutions.

In contrast, a systemic partnership works to change underlying dynamics. Taking the issue of packaging again, a net positive company would go beyond working with peers on new materials. It would advocate for, and help design with governments, better policies to create a circular economy, change consumer habits, eliminate plastics from certain uses, and support public-private financing to fund new recycling infrastructure. These are the kinds of structural and business model changes that address the packaging issue in the longer term. A systems-level partnership needs all three societal players at the table: the private sector, governments, and civil society. We call that It Takes Three to Tango. Efforts to reset systems fall more into advocacy—not entirely, as sometimes action demonstrates what’s needed in terms of policy, but mainly.

Making the “tango” partnerships happen depends on first showing success with 1+1=11 alliances. Until you demonstrate positive, measurable change for the sector or value chain, it’s hard to be taken seriously in larger conversations with all stakeholders.

No categorization is perfectly clean. The real world is messy, and approaches can blur into each other. You can start with a sector project and expand it to work on a bigger system. But before diving into partnerships, we want to explore quickly the mix of initiatives a company embarks on and provide a sense of what a net positive company’s portfolio of efforts will look like.

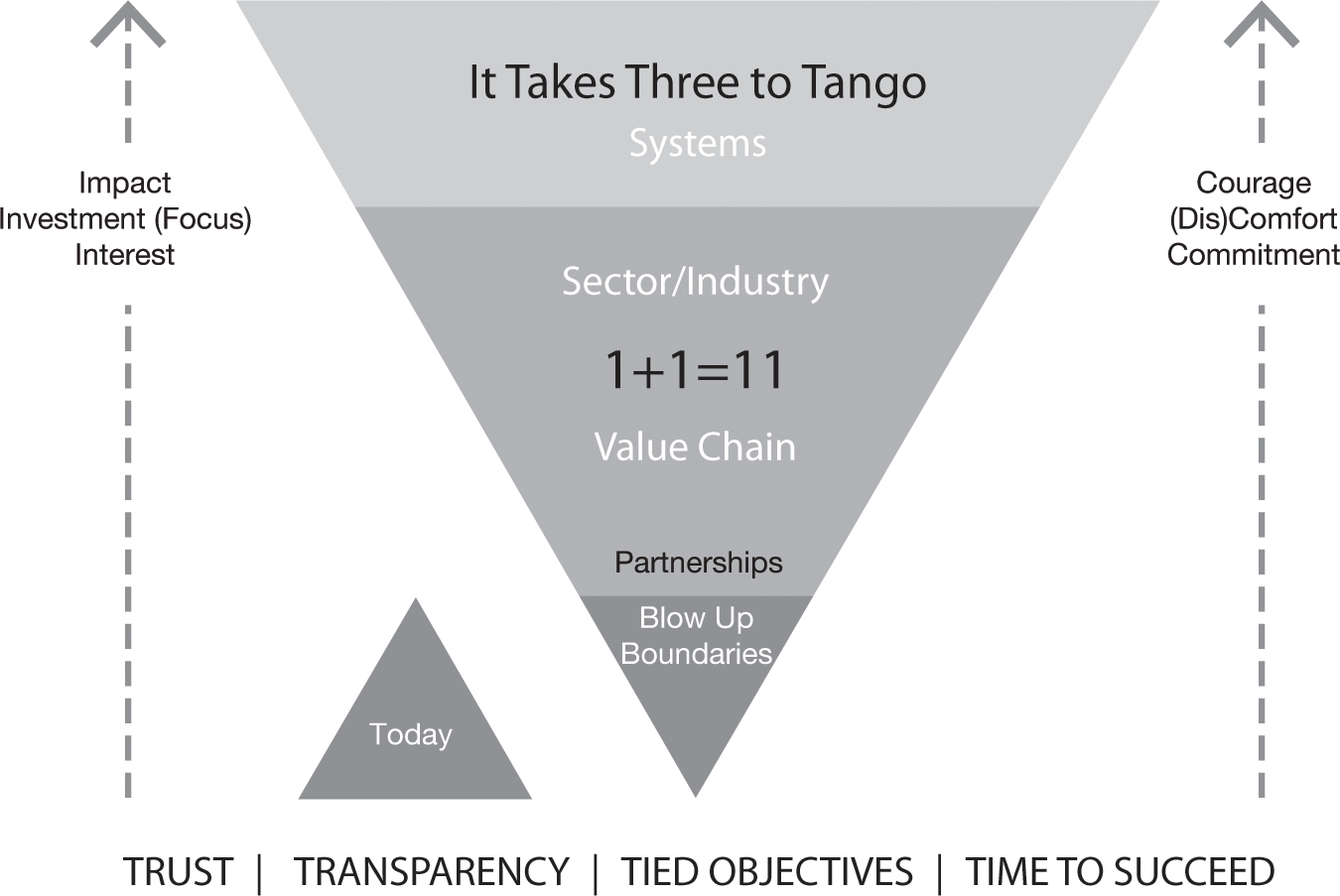

The Mix of Initiatives Today and Tomorrow

Consider the programs or initiatives a company works on under the banner of sustainability. In total, those initiatives will create some impact—a reduction in negative outcomes or an improvement in positive ones. Think of the total effect you have across initiatives as a pyramid (see figure 6-1).

The first efforts, shown at the bottom, generally start internally, working on one’s own footprint within the four walls of the business. You may cut carbon emissions through reductions in energy use, for example. Even with targets such as zero waste, which force you to think bigger and blow up boundaries (chapter 4), the impact is limited by the company’s own footprint. This is critical work, and net positive companies understand that the problem starts at home. You have to earn a seat at the table by getting your own house in order.

Above that base we show partnerships that extend the work beyond the company, starting with the value chain. For most sectors, the environmental and social impacts of the business fall largely in those Scope 3 emissions, so the potential for impact is bigger. Moving up the pyramid, the work ventures further out to sector-level projects, and potential positive impact grows. The reality of these sector partnerships, however, can fall short of expectations. Too many companies are unwilling to assume responsibility beyond their own operations. Or the value chain partnerships remain transactional and focused on extracting the lowest cost for everyone. Net positive companies take broader ownership and look for greater wins—they understand the vast power of partnership.

FIGURE 6-1

Mix and impact of initiatives (today)

The top of the pyramid is where the full systems change collaborations come in (those we take up in chapter 7). We draw the pyramid with this shape to indicate, directionally, that most of the work today is at the bottom, with internal efforts. A single, well-run sector partnership to reduce impacts across the industry could dwarf the individual work, but there are still few of those broader collaborations. Companies are also somewhat wary of venturing out of their comfort zone into these partnerships. The mix of initiatives today, then, is weighted to the easier-to-manage, smaller-impact ideas—the pyramid is bottom heavy.

A net positive company’s mix, however, will look radically different (see figure 6-2). Driven by purpose and an understanding of the imperative, the company’s efforts will shift dramatically upward. They will unlock bigger value by building strong alliances that involve the value chain, sector, or full systems. In this future scenario, today’s four walls efforts (shown in the small shaded triangle next to the big pyramid) are still science-based and comprehensive—such as going to 100 percent renewable energy—but the total impact is tiny in comparison to what value chain, sector, and systems partnerships achieve.

FIGURE 6-2

Mix and impact of initiatives (tomorrow)

As you move up the scale, there’s more impact and interest from all stakeholders, but it takes more courage, commitment, and investment of energy and focus. Success breeds success, and the bigger thinking comes from having solid 1+1=11 partnerships operating successfully.

Partnership Challenges

The potential for net positive outcomes is large and worth the effort, but partnerships are challenging, especially as the mix of players expands. The larger the scope, the more complicated it is and the more points of failure you can run into. The number of corporate alliances grows every year, but an estimated 60 to 70 percent fail.3 A prodigious collaborator like Unilever has seen many fall short. Partnerships can underperform for many reasons.

Misaligned visions and objectives. Even with consensus that there’s a problem, organizations have different motives for being in the room. Steve Miles, the former global brand EVP for Dove, says, “You need an intersection of interests, but don’t expect the Venn diagram to perfectly overlap—that can’t happen with an NGO.”4 Unilever may focus on sustainable sourcing for a commodity, covering multiple environmental and social dimensions, whereas an NGO, such as Oxfam, might zero in on livelihoods and decent wages. It’s not incompatible, but it’s not exactly the same either.

No clear understanding or agreement on what each brings to the table. In the United States, a promising partnership that Unilever had with energy company NRG didn’t go as planned. The goal was to set up a new kind of business relationship to provide a strategic portfolio of clean energy projects across multiple facilities in North America. But neither company was organized to execute on that goal, and each thought the other party had capabilities it didn’t. So they fell back into one-off renewable energy projects, negotiated at each site separately. Similarly, in another partnership, Unilever and the NGO Acumen were aligned in principle, but found that their scales were not in sync. Acumen worked with smallholder farmers and co-ops, while Unilever needed to find solutions for sustainable sourcing an order of magnitude larger.

Ill-defined or lacking metrics on business value. Partnerships, especially the full systems ones, are hard to put a value on (in the traditional, short-term, shareholder maximization mindset). A food company might spend money today to meet healthier food guidelines by reducing salt, fat, and sugar. A short-term view would say it’s not worth it. But the investment can pay off in growing markets for healthier food. There’s a “greater good” argument as well—unhealthy societies don’t thrive. Also, without good metrics, collaborations can lack the frequent feedback loops they need to adjust course.

Cultural challenges. Business executives can find it difficult to deal with competitors, NGOs, and governments around the same table. Leaders need new skills—listening, finding common ground, and convincing people to commit time and resources. Chief sustainability officers are often well prepared for this work, having had to “matrix” in their companies to get anything done.

Unilever, even with all its successes, has had failures that demonstrate all of these hurdles. In one large collaboration, Unilever, Mondelez, DSM, the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, and the World Food Programme came together for a five-year initiative to tackle child undernutrition. The program, part of a larger multistakeholder platform called Project Laser Beam, was well funded—$25 million each from the companies—and the partners were experienced. But it didn’t result in long-lasting improvements. The project was designed top down and globally without enough focus and coordination at the local community level. There weren’t solid metrics and output measures, so they lacked a feedback loop. But mostly, a misalignment of objectives weakened the effort.

Partnerships can become talk-fests, lacking scale and impact. A net positive company, however, unlocks the power of these partnerships; it does fewer, but bigger ones to increase impact. Less is more, if done well. Robust and lasting partnerships also have a long-term commitment—they are embedded in the company, and not subject to support from individual executives.

With hurdles out of the way, let’s move to the pathways to greater performance. We can jump these hurdles, and there are excellent examples to learn from—not as many as we need yet, but real successes.

Making 1+1=11

We won’t focus here on the general elements of a good partnership, which are, in theory, not too hard to figure out (they’re the flip side of the challenges). The difference in these collaborations, then, is not how to manage them, but the overall purpose and approach. They are intended to serve the larger good as much as help the partners themselves, and have impact, scale, and staying power.

We will run through examples from six approaches to net positive partnerships with varying and expanding partners:

- Within your value chain

- Within your industry

- Across sectors

- With civil society

- With governments (nonsystems)

- In multistakeholder groups (nonsystems)

The lines here aren’t set in stone, and a given partnership can run through multiple approaches in its lifetime. But it’s helpful to start by identifying the shared problem you’re trying to solve and who needs to be at the table. The goals here are working at a deeper level than just “cut emissions” or “reduce human rights problems with my suppliers.”

We try to use examples with a track record and outcomes to point to, which shows commitment and consistency over time. Let’s look at the six approaches.

Partnering within Your Value Chain

The first step out of the safety of your own operations is to reach out, in genuine partnership, to your direct value chain. It’s the start of expanding your sense of ownership—net positive companies don’t outsource their lifecycle responsibilities. This is the biggest immediate unlock in value, given the much larger total footprint in the value chain. There are often enormous savings or higher revenues if you work better, in trust and cooperation, with suppliers and customers.

If you take the short-term, profit-maximizing view on business, you see suppliers in purely functional terms—they’re just companies that serve you at the lowest possible cost (so you can keep margins high and please investors). This is a somewhat exaggerated description, and few companies are that coldly removed from suppliers they’ve been doing business with for years. But it is the prevailing model in many sectors—fashion companies, for example, will change suppliers on a dime for a penny in savings. For a long time, Unilever suppliers felt like the relationship was purely transactional, which was true—the company’s buyers had a traditional cost-cutting mindset. Unilever saved money, but lost out on greater value.

Flipping the script and serving suppliers will help you both, ultimately, serve the customers or citizens at the end of the value chain. That’s the real change needed to create a net positive effect. You build the pie together instead of splitting the pie differently. Early in the development of the USLP, Unilever set uncomfortable goals and made it clear that it could not reach them alone. It made partnership a deliberate cornerstone and launched a new program called Partner to Win to create a stronger bond with suppliers.

Marc Engel, Unilever’s chief supply chain officer, says, “We wanted suppliers to be excited about the journey and join us.”5 Unilever also needed significant product innovation to shrink its footprint and hit the USLP targets. Like all CPG companies, Unilever takes credit for innovations, but most of the time, suppliers create new ingredients and invent new product benefits. Unilever can implement and scale those new ideas, but it gets the bulk of its innovation from supplier R&D.

Before the USLP launched, Unilever’s suppliers did not view the company as a place for innovation. The suppliers were not bringing them new ideas. It was a huge lost opportunity. When you’re a big customer, Engel says, “you’re partly paying for the supplier’s R&D, so the question is, are you getting the benefit, or is someone else?”6

The goal of Partner to Win was to become the trusted customer of choice and the preferred innovation partner for major suppliers. Engel admits it was an odd fit for him at first. But Paul took Engel on a trip to meet four major suppliers and experience how nonstrategic the relationships were. The new program asked the top 100 suppliers, which provided a significant percentage of the company’s inputs, to develop joint business plans with a five-year horizon. Unilever gave accountability for key supplier relationships to each of the top 50 executives in the company—all executives, not just buyers. Paul was responsible for two relationships (including top supplier BASF); the chief R&D officer owned two; the head of deodorants, three; and so on.

Through Partner to Win, Unilever built strong bridges, which paid off as suppliers increasingly brought them new ideas. The list of joint innovations that use suppliers’ best technologies to solve a societal need is now long. In just one category, products that help people in water-stressed regions, Unilever launched soaps that kill bacteria faster, one-rinse softeners, and waterless shampoo. The company also worked with sustainability leader Novozymes to replace some chemicals in detergents with enzymes. The new formulations cleaned clothes as well, but at lower temperatures, a major win for reducing carbon emissions in the use phase of the product.

Deeper relationships pay off in paradoxical ways: if you only look at price, you won’t get the lowest price. It sounds ridiculous, but it’s only when you work with suppliers to coordinate innovation investments and improve overall cost structures—without obsessing about the price per unit—that you really get better prices. So, don’t focus on the number, but on joint value creation. Don’t focus on the transaction, but on the customer you both serve. As always, there’s no way to work this closely, and share savings, without a deep well of trust.

Marc Benioff, the CEO of Salesforce, tells a story about meaningful connections between customers and suppliers. In his book Trailblazer, he describes a visit with David MacLennan, the CEO of Cargill, the largest privately held company in the United States and a big Salesforce customer. They walked out of Benioff’s office and saw a dozen people wearing Salesforce “trailblazer” T-shirts. MacLennan asked him, “Are those your employees?” Benioff said, “No, they are your employees … but they use our technology so they have become part of our family.”7

Net positive companies partner with innovative suppliers to develop and test new technologies that slash footprint or improve lives. While Apple was becoming essentially carbon-free in its own operations, it also looked for carbon-reduction solutions across its value chain. In a fascinating move, the company partnered with mining giants Alcoa and Rio Tinto to cut emissions in aluminum smelting. The metal is one of the most recycled materials in the world, but new aluminum production is incredibly energy intensive, creating about 1 percent of total global carbon emissions (and one-quarter of Apple’s product manufacturing footprint).8

The joint venture the three companies created, ELYSIS, developed a carbon-free smelting technology that emits only oxygen. At scale, they expect it to reduce operating costs by 15 percent with higher productivity. Apple invested $13 million in the venture, provided technical support, and then bought the first batch of ELYSIS aluminum at the end of 2019.9 Apple’s VP of environment, policy, and social initiatives, Lisa Jackson, said that “for more than 130 years, aluminum has been produced the same way … that’s about to change.”10 Apple doesn’t make a dent in global aluminum use (think: cars, cans, and construction). But it’s plenty big enough to lend its brand and demonstrate proof of concept, which helps attract other aluminum buyers. That’s already happened—Audi is using ELYSIS zero-carbon aluminum in the wheels of its new electric sports car.11 With more momentum, the joint venture can shift the industry toward massive carbon reductions, making it a large net positive play for Apple, and a tipping point for the world.

As you take on more responsibility for impacts and find ways to increase your handprint along the value chain, you’ll need more of these relationships. They unlock tremendous value, build resilience, and increase transparency, traceability, and trust. Unilever invested in trust during the initial Covid lockdowns by, as we said earlier, setting aside €500 million to support its suppliers and extend credit to customers.12 That’s net positive financing.

What Net Positive Companies Do to Maximize Value Chain Impact

- Take responsibility for their total value chain impacts and assess areas with the biggest potential for collaboration

- Treat suppliers as partners and family, not as low-cost providers of commodities, and look for joint value creation versus value transfer

- Build trust and transparency with their suppliers and customers through aligned objectives and incentives and, in some cases, open books

- Identify large challenges holding back the industry, and large opportunities to improve lives, or test new technologies together

- Start and end with the citizens they serve in mind

Partnering within Your Industry

As you expand your horizon and your view of responsibility, it becomes clear that you and your peers share many challenges that would benefit from cooperation. These issues may be impossible to solve alone, too costly, or need to be attacked at an industry level because they drag everybody down. With issues such as slave labor in apparel or e-waste for tech, for example, if one competitor looks bad, they all look bad (and the reverse holds as well). Net positive companies work actively with peers to change industry norms, reduce combined impacts, and greatly improve outcomes and the sector’s image.

Companies shouldn’t be one-upping their competitors on shared challenges and opportunities. What good does it do if, say, only one food company tackles child labor problems in West African cocoa production? The issue is better solved collectively, in a “precompetitive” way. Likewise, when Merck helped J&J produce its Covid-19 vaccine to speed access, it put the world and its sector ahead of itself, helping a much-criticized industry garner praise.13 Net positive companies understand that despite the pressures to perform, we should not compete on the future of humanity.

Bringing major peers together reduces risks and costs of the whole endeavor (it’s not completely new for sectors to work on general cost-cutting, so why not on sustainability programs also?). The expense will end up less per company, and the system will be more robust. A net positive company is happy to take the lead and invest in better solutions if peers quickly follow. But it helps to create a sense of urgency and movement, and an understanding that it’s not optional. Get enough companies in one room and, as Dow’s former CEO Andrew Liveris says, “you gain speed and mass.”

The number of industry collaborations is picking up, and they have diverse aims. Let’s look at a few of the goals that sector-wide collaborations can pursue. These efforts can have broad impact and prepare companies for larger systems and net positive work down the road:

Implementing industry-wide operational improvements. Industry alliances can find ways to greatly improve how the sector operates at a tactical level—there are plenty of opportunities down in the trenches. The Consumer Goods Forum (CGF), which Paul helped found in 2009, brings together four hundred consumer goods retailers and manufacturers with $4 trillion in combined revenue. The industry worked together at times before CGF, but in a less focused way. They continue to collaborate on issues such as food waste, human rights and forced labor, health and wellness, packaging, and avoided deforestation. The group hasn’t always lived up to its potential, as some members play it too safe or stall on tough issues—with an unwieldy fifty-five-member board, talking about human rights or other complex issues can feel like pulling teeth.

But when there’s a clear connection to efficiency and cost savings, the conversation goes more smoothly. The sector has had a number of solid successes in improving operations across companies. For example, the partners standardized the size of shipping pallets globally. For context, there are more pallets in the world, about ten billion, than people.14 When billions of stacks of products move in and out of trucks, warehouses, and stores, inefficiencies add up. With a small number of standard pallet sizes, fulfillment is quicker and companies can pack trucks up to 58 percent tighter, saving significant fuel and carbon emissions.15 CGF members developed, agreed to, and implemented these standards, together. The benefits accrue to both individual companies and the collective.

Tackling the highest impact sectors. The Mission Possible Partnership, led by the Energy Transitions Commission, RMI, We Mean Business, and the World Economic Forum, is assembling companies from high-energy-intensity sectors: aluminum, aviation, cement and concrete, chemicals, shipping, steel, and trucking. The goal is technological disruption and developing sector roadmaps for the transition to a low-carbon world.

Sharing best practices. The food and agriculture sector covers 40 percent of the world’s land surface, uses 70 percent of freshwater, and produces up to one-third of greenhouse gas emissions.16 CGF launched a coalition to tackle food waste, which Denis Machuel, CEO of Sodexo, calls “the food sectors’ single most important climate action.”17 Our future depends on this sector—which will have to feed many more people—getting it right. The World Business Council on Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and its chairman, Sunny Verghese, CEO of the Singapore based agribusiness Olam International, created the Global Agribusiness Alliance (GAA) for food suppliers. Their goal is to share best practices for reducing operational impacts, managing soil and land use (which could lead to carbon sequestration), enhancing livelihoods, protecting water resources, and cutting out food waste. The focus is on developing more specific action pathways because what business does well, Verghese says, is not theorizing and modeling, but executing.

The big players are on board because the motivation is both carrot (collective work is more effective) and stick; they avoid, as Verghese says, “the rap of big, bad agribusiness … just like big, bad pharma or big, bad energy.” Verghese is clear-eyed on the challenges. “We are an intensely competitive industry, so we will never come together unless the world is literally burning down,” which he points out is happening. (It gives new meaning to the phrase “burning platform for change.”)

Getting to tipping points. To catalyze more sector partnerships, Paul cofounded IMAGINE, a foundation and for-benefit company, with former Unilever execs Jeff Seabright and Kees Kruythoff, and with transformational leadership expert Valerie Keller. They focus on transforming sectors by bringing together a critical mass—at least 25 percent of the total value chain—to reach tipping points. One initial target is the fashion sector, a $2.5 trillion behemoth with an enormous environmental footprint in water and material waste (73 percent of clothes end up in landfills or incinerators), and a serious problem with over-consumption (the growth of fast fashion).18

IMAGINE has helped the Fashion Pact, led by Kering CEO François-Henri Pinault, design a pathway to manage their shared impacts on three major challenges: climate, biodiversity, and oceans. The members agreed to science-based carbon reductions in keeping with the global 1.5°C goals (cut emissions in half by 2030 and to net zero by 2050), including a move to 100 percent renewable energy by 2030. The biodiversity plan includes commitments to regenerative approaches for cotton, and the oceans work focuses on eliminating single-use plastics and microfiber pollution. None of these companies could do this work alone.

Committing to codes of conduct and standards of practice. Standards are not sexy, but better standards and data can greatly improve environmental and social outcomes. A decade ago, the Sustainable Apparel Coalition created the Higg Index, a tool to help brands and retailers consistently measure a company or product’s sustainability performance. Similarly, the information and communication technology (ICT) industry’s Responsible Business Coalition commits members to imposing a shared code of conduct (tied to multiple standards, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) on themselves and tier one suppliers.19 A coalition of large mobile providers has also committed to joint science-based targets for greenhouse gas reductions.20 These commitments can drive a sector toward net positive. Obviously, intentions and standards are not outcomes. But when standards drive substantial changes in company operations, they result in sizeable reductions in footprint across a sector. Most standards are not targeting net positive outcomes, yet, but they engage sectors and open companies up for bigger thinking later.

Solving new problems before they get big. As the use of clean technologies grows exponentially, these industries are getting larger, with their own environmental or social problems. For example, as wind power advances, older turbines get retired. There are few options for handling these used football field–length blades—they’re not easily recycled. Owens Corning, which makes materials that allow the blades to grow longer and stronger, estimates there will be a quarter million metric tons of blades needing an end-of-life solution within two years. The company is taking responsibility for the life cycle and collaborating with peers in the American Composite Manufacturers Association to find solutions such as extending the life of the blades or stripping metals and turning them into pellets for packaging and other uses. They’re working together to find solutions they can scale.

Testing or accelerating new business models. In an innovative test that’s challenging norms, the Loop program, led by TerraCycle, is working with CPG giants, including Body Shop, Honest Company, Nestlé, P&G, RB, and Unilever, as well as retailers Carrefour, Kroger, and Walgreens. The program gives consumers their favorite brands in reusable containers. When people are done with the shampoo, ice cream, or other products, Loop picks up the box, cleans the empty bottles and cans, and refills them. It may or may not work, but it’s worth the experiment.

What Net Positive Companies Do to Shift Their Own Industry

- Lead sector partnerships to address the biggest shared hurdles and opportunities to help the world thrive

- Gather a critical mass, roughly 25 percent of sector production or more, to work together and create tipping points

- Worry less about who gets the credit, or how to compete on issues, and focus on broader solutions

- Identify operational shifts that save everyone money, resources, and footprint

- Develop joint standards, such as how to best measure sustainability performance, or science-based goals that members individually, and the whole sector, can shoot for

Partnership across Sectors

Once sector players are comfortable working together, they can expand their efforts and work with other sectors that face similar issues—they may share parts of a supply chain, for example. These are some of the largest and most impactful 1+1=11 partnerships. They help companies get past inefficiencies of scale.

The stresses of a volatile world are bringing strange bedfellows together. The pandemic drove companies across sectors to jointly solve problems. During the initial rise of the virus, it was clear the world needed more medical equipment, and fast. Unilever joined the Ventilator Challenge UK consortium to combine resources and quickly make more ventilators. Partners included Airbus, Ford, multiple Formula 1 race teams, Rolls-Royce, and Siemens (and Microsoft for IT support). This was a short-term partnership, but others like it may work out over many years.

One of the longest-standing and successful joint efforts brings cross-sector peers together with suppliers (with a critical assist from an NGO convener) to work on new cooling technologies. The refrigerants that have dominated the industry for more than a century, chemicals in the fluorocarbon class (CFCs and HFCs), do enormous damage to the climate. They have high global warming potential, meaning they trap more heat than a similar amount of carbon dioxide—up to eleven thousand times more over a twenty-year period. Some damage the ozone layer as well.21

In the 1990s, a few companies started working on better solutions. The group, Refrigerants, Naturally!, was founded in 2004 by Greenpeace with Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, and Unilever (PepsiCo and Red Bull are now core partners as well). The group has focused largely on refrigerated cases and vending machines, working with chemical suppliers to create sufficient market demand for substitutes. The new options include, ironically, hydrocarbons and CO2 itself, which has zero impact on ozone and, by definition, a global warming potential of 1.22 After scaling up for a decade (these things take time), the partners stopped procuring machines with fluorocarbons in 2017. Coca-Cola hit its one-millionth unit with new technology in 2014, and in total, the group has put more than seven million units into service.23

Looking back on what has made this partnership effective, Amy Larkin, formerly of Greenpeace, comments that her global NGO worked with a few leadership companies first. They moved the technology forward, “and then, together, we moved a multitrillion dollar industry” (they also had the clout to pressure governments to change global regulatory standards, venturing into Three to Tango territory).24 This multiplier effect is what makes 1+1=11, and together, Larkin says, they will cut an impressive 1.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions over twenty years. The progression from an NGO with an idea to implementing a new technology at scale came from having the right cross-sector mix in the room.

This successful example of a multiplayer partnership helped define what precompetitive looks like (see the box “Don’t Worry about What’s Precompetitive”). At the time, nobody was pitching soda or ice cream on how it was refrigerated. Consumers are much more aware of the environmental and social aspects of what they buy now, so there’s more pressure to solve shared challenges. In particular, packaging and plastic are pressing issues. A couple of innovative partnerships are searching for new models.

DON’T WORRY ABOUT WHAT’S PRECOMPETITIVE

To solve problems at scale, competitors need to work together. But it’s hard to say which issues are precompetitive and which could give you an advantage. When the refrigerants coalition came together, nobody was competing on how they cooled their machines. But times have changed. Some consumers may, in fact, buy something based on the complete story of how it’s manufactured or distributed. But either way, working together should be the default option. Step back and ask yourself, is this a problem that makes everyone in the sector look bad? Is it something that we can’t solve alone? Or on social issues, like racial equality, consider how unhelpful it is for just one brand to be a champion. Embrace transparency. You should rarely hold back proprietary information about a shared challenge. If you do, you may see some short-term advantage, but you’ll never get the 1+1=11 benefits that solve the problem for all. Start with trust, do what’s right for the community and the sector, and then worry about how to take advantage of it. Once you’ve reduced shared hurdles, you’ll find that companies are not equally prepared to act quickly. If you’ve built a net positive business that’s aligned around purpose, with people who have a mission, your company will move quicker and reap the benefits faster.

Spirits giant Diageo recently created a new beverage sector partnership, along with a small sustainable packaging company, Pulpex Limited.25 They invited PepsiCo and Unilever to test out a nonplastic, paper-based container. It’s a smart collaboration since the companies mostly operate in different spaces—alcoholic beverages, nonalcoholic drinks, and consumer packaged goods. It allows some scale without direct competition.

Retailers and CPG companies are experimenting with ways to greatly reduce packaging, or even eliminate it. British retailers Asda (owned by Walmart), Morrison, and thirty others teamed up to offer packaging-free options in stores.26 Consumers fill their own bags and jars from bins holding grains and nuts, detergent, shampoo, and many other products. In Indonesia, Unilever partnered with a packaging-free store to offer eleven brands from what look like soda machines, but dispense TRESemmé shampoo, or Lifebuoy and Dove soaps, instead.27 The shape and look of packaging has long been part of a brand’s image, but in the end, it’s not the purpose of the product. And, unique packaging that can’t be reused creates pollution, a net negative.

It’s possible that all of these efforts will be failures, or they may not reduce total impacts as hoped. Is it better to ship reusable bottles and then clean them, or would a more robust recycling infrastructure with 100 percent recyclable packaging achieve lower impact? There’s only one real way to find out: real-world testing, measurement, and sharing of outcomes. These partnerships are invaluable learning experiences, even if they stumble, as long as we fail fast, fail forward, and move on.

What Net Positive Companies Do to Solve Problems across Sectors

- Identify key challenges that cross industries and form broader coalitions to solve them—issues such as education, joint energy buying, human rights, labor laws, and climate change are some of the many that offer fertile ground

- Develop new business models by putting unlikely industries together

- View their responsibility to stakeholders extending beyond their own industry footprint

Partnering with Civil Society

Most large companies have some basic partnerships with civil society organizations—an annual United Way fundraising effort, or supporting a cause in developing markets, or a pet project from the CEO. Many are CSR-style initiatives—essentially cause-related marketing. They are little more than donations, and not real collaborations. A company can sprinkle some money around with limited effort, since it doesn’t require much in the way of people resources or planning. At best, the program is linked to a brand, but far removed from the overall company strategy.

Companies often shy away from deeper partnerships with stakeholders outside the private sector, such as academics, NGOs, or philanthropies. But net positive companies seek out civil society partners to make their businesses more effective and resilient. They embrace partners for their knowledge, passion, ability to solve problems, and close relationships with communities. In these richer collaborations, the stakeholders are more than just places to donate money to, or conveners of meetings; they are major actors in executing a program.

Unilever, like all companies, started with more standard, somewhat shallower CSR-style work. The company had a history of a “100,000 flowers blooming” approach to NGO engagement. They were spreading the philanthropy fertilizer around, with little coordination. All of it was well intended, but not necessarily impactful. Around the time Paul arrived at Unilever, Rebecca Marmot (now the chief sustainability officer) came to the company to take a global role working on advocacy, policy, and partnerships. She collected information on Unilever’s philanthropic and brand-related partnerships and was shocked at the volume. “We lost count when we got to four thousand different partnerships,” she says.28

Part of her job, with Paul’s urging, was to make sense of it all. They quickly centralized efforts from all over the world and across hundreds of brands, focusing on key themes, such as health and hygiene, food and nutrition, and livelihoods. Then, they moved into deeper, more strategic relationships with only five global NGOs: Oxfam, PSI, Save the Children, UNICEF, and the World Food Programme. Once there was centralization, then they could decentralize, but do it strategically, letting local markets customize and leverage the larger relationships. The big efforts were handled globally for maximum impact, but they reserved 25 percent of the partnerships budget for local initiatives.

This focused partnership model helped Unilever work on larger, more coordinated efforts, which ensured that the global and local efforts reinforced one another and tied into the business. One program, dubbed Perfect Villages, worked with NGOs to help local communities develop more holistically. They partnered with schools to improve education, helped local businesses get microfinance, worked to improve local infrastructure, and more.

Unilever and UNICEF have collaborated productively for a decade, on WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) issues and through multiple major initiatives with key brands, such as Lifebuoy’s hand-washing campaign and Domestos’s efforts to provide safe sanitation (which has brought access to toilets to thirty million people). Charlie Beevor, now Unilever’s VP of homecare, worked on the Domestos brand early in the collaboration with UNICEF. The program, he says, was directly tied to the brand’s purpose, connecting it “to an intractable societal problem affecting 2.3 billion people.”29 The story of fighting for improved sanitation has been integral to the product; Beevor says the mission has been proudly and prominently displayed on roughly 270 million Domestos packages. Marmot also makes it clear how important this connection is, saying, “If you really want to change the way business operates, then surely you need to mainstream this way of thinking into the absolute core of the business, not keep [partnerships] as a separate thing.”30

When NGOs and companies have respect for one another as teammates, they can up one another’s game. NGOs often go to shareholder meetings to apply pressure on management on issues of concern. When NGOs came to Unilever’s annual meetings, Paul liked to show, when he could, that the company was already planning to go further on an issue than the NGO was advocating for. The game was to push the NGO to then use its leverage over other companies in the sector, making everyone go faster. Having good relationships with NGOs is critical. In ten years at the helm, no NGO seriously attacked Paul or Unilever—not Greenpeace, Amnesty International, or Transparency International. It wasn’t because Unilever was perfect; it was about relationships, partnerships, trust, and a desire to continuously push the boundaries.

NGOs give a business credibility on the ground, but a net positive company has to build deeper, direct community relationships as well. That often means working with the true power holders in most developing country communities, the women. Unilever Vietnam ran a local program to teach kids about dental hygiene. They partnered with the ministries of education and health, bringing dental trucks to schools for free checkups. But to get kids and families to participate, they also needed the support of local women’s associations, the largest of which had one million members. With their support, the initiative was wildly successful. Over ten years, the program reached seven million children. The incidence of tooth decay in kids under age ten plummeted from 60 to 12 percent.

The Shakti initiative is another of Unilever’s successful programs that enhance communities by working with women. The program operates in many countries (under multiple names), but it is largest in India. In more rural communities, Unilever partners with local women, focusing on those in disadvantaged situations. The company teaches them how to set up shop and sell small amounts of Unilever products. The program obviously has commercial benefits as well—it’s a distribution channel to remote villages. Shakti has gotten to scale—tripling in a decade—and is now part of the mainstream business, making a sizeable contribution to Hindustan Unilever’s revenues. But the economic and social impact for the 136,000 Indian women in the program is even more significant. As Hindustan Unilever chairman Sanjiv Mehta says, “Their status in the village and family rises, and they increase their family income by about 25 percent.”31 It’s hard to imagine a better net positive win-win than that.

Even without a direct connection to sales, Unilever helps enrich the communities it operates in. In Assam, India, where it had plantations (it has since sold them), the company ran the only school in the region for the disabled, placing it right by the factory. Most companies would feature that story in an annual report as a big deal. Net positive companies think it’s just a normal way of doing business.

What Net Positive Companies Do to Build Successful Partnerships with Civil Society

- Work with NGOs and communities strategically, not solely in philanthropic CSR initiatives, and make these partnerships an integral part of their longer-term strategy

- Embed these efforts in their businesses by focusing their NGO and community work where they can best improve well-being through their business and brands

- Treat civil society organizations as equal partners and cherish their advocacy for the voice of the people

Partnering with Government (Nonsystems)

The most challenging partnerships are often the ones with governments, but given their reach and scale, these collaborations can have the highest impact. We’re not talking yet about real systems-level change (see chapter 7), but focusing for now on opportunities to help communities develop and make the business operating environment better for all.

Companies bring a range of skills and capacities that help governments be more effective, especially in developing countries. Adopting a collaborative attitude toward government, instead of the normal adversarial tone, can lead a net positive company to work on surprising issues. Unilever helped the Vietnamese government develop pension systems and stock ownership plans so the company could offer employees the same benefits everywhere. Unilever has helped many governments build capacity and knowledge to fight the blight of counterfeit products (which sucks revenue away from businesses and communities). The company has even trained tax inspectors in Colombia, Nigeria, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and elsewhere. They help these countries create, enforce, and mechanize a better tax system—one that is efficient, broadens the tax base, collects more of what’s owed (so the country can invest in development), and creates a level, predictable playing field for multinationals.

People from other companies often ask Unilever why it does this kind of nitty-gritty government work. The benefits are many. Being a good partner on taxes builds trust with authorities, which makes all government partnerships more productive. It opens up discussions around other regulatory issues, such as building recycling systems to help with packaging and waste goals, or creating incentives for nutrition and micronutrient programs. Unilever found it could work effectively with these governments on many strategic issues because of their ongoing relationships on tactical issues, such as taxes.

Net positive companies bring their best practices from other countries to solve shared problems. For example, multinationals in the consumer products industry have largely abandoned the practice of animal testing, with the painful exception of products sold in China and Russia where they require it. Unilever worked in both countries to change policies, but brought in alternative testing technologies, which have now saved millions of animals. The work has turned one powerful critic, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), into an ally. Consider how difficult it is for PETA to have a productive conversation with the Chinese or Russian government. A company with significant operations in these countries can broach tough subjects that PETA can’t. The NGO now allows Unilever to use its cruelty-free label, which attracts customers, on brands such as Dove, Simple, and St. Ives. This is what value from values looks like.

It can be challenging to hold on to your ethics in some situations. Many countries are rife with corruption, and some leaders and governments are doing horrible things to their own citizens. Working with administrations with troubled policies is complicated, but in essence, some things are nonpolitical. When President Narendra Modi in India launched the Swachh Bharat Mission (which means “Clean India”), one key goal was to get a toilet into every household. This was an opportunity for Unilever and UNICEF to expand their sanitation programs. Giving every Indian a toilet is not political. Multinationals see leaders come and go, and a net positive company finds a way to move things in the right direction no matter who is in power.

Did Unilever always succeed? Not exactly. In 2017, when the last US president was about to take the country out of the Paris climate accord, Paul and the chief sustainability officer at the time, Jeff Seabright, pitched the administration on staying in the global agreement. They got in to see the president’s daughter and son-in-law. We know how that one ended. Sometimes you succeed, and sometimes you don’t.

What Net Positive Companies Do to Work Productively with Governments

- Use their knowledge and skills to help governments develop capacity, improving the business operating environment for all

- Seek areas where the playing field needs to be leveled and governments are willing to actively engage

- Don’t walk away from governments they don’t agree with, but try to partner and improve the well-being of citizens

- Understand what’s short-term and political versus what needs to be focused on for the long term

Partnering with Multistakeholder Groups (Nonsystems)

The most sprawling and complicated 1+1=11 partnerships bring everyone to the table—peers, suppliers and customers, governments, NGOs, academics, and finance. This is when magic can happen, but it’s also where too many ingredients can spoil the soup. It’s a tough balance. The collaborations we look at here are improving and scaling what works within the current system … but are not yet resetting whole systems.

Unilever has found multistakeholder work to be highly effective in the tea industry. It’s a big business, but the sector is anchored by more than nine million smallholder farmers around the world.32 Eastern Africa is a major source, with 500,000 farmers in Kenya and 40,000 in Rwanda (the country’s third-largest employer).33 As a big buyer, Unilever has had a significant presence in the region for a century. Whether these communities thrive reflects directly on the company. Moving to more sustainable practices in farming—managing soil health or reducing pesticides, for example—enhances livelihoods, productivity, and the quality of the tea. But that takes years. Farmers need financial support or guarantees from buyers to shift to better practices.

In Rwanda, Unilever partnered with the national government, the Wood Foundation, IDH (a Dutch NGO), and the UK Department for International Development to develop a new tea plantation. Unilever committed $30 million over four years—what the Wood Foundation referred to as “patient capital”—to develop the farms and a tea processing center in one of Rwanda’s poorest areas, the Nyaruguru district.34

The collaboration provided tens of thousands of people with livelihoods—farmers, factory workers, and people in support structures, such as schools. It also offered technical assistance and training on the efficient use of resources and how to develop resilience to drought and climate change. Unilever built clean water infrastructure for worker households as well. The program created a virtuous circle of economic, environmental, and social development in one supply chain and region. That’s the 1+1=11 outcome. To make it happen, Unilever needed the partnership of NGOs and local governments, but in this case, could do it without peers. Creating both new producers and consumers in Rwanda is a good example of “bottom of the pyramid” market development, a strategy that adviser C.K. Prahalad brought to Unilever.

Creative multistakeholder partnerships can fill big gaps in a community’s development. A lack of safely managed sanitation systems, for example, keeps billions of people from thriving. In many communities, if there’s sanitation at all, they treat the sewage and put it back in waterways. They miss out on capturing the nutrients, which can be a feedstock for fertilizer, fuel, and energy (anaerobic digestion turns waste into valuable biogas).

The Toilet Board Coalition (TBC), with founders Firmenich, Kimberly-Clark, LIXIL, Tata Trusts, Unilever, and Veolia—plus fifty stakeholder partners, including UN agencies and the World Bank—is trying to solve this problem by creating a for-profit market for sanitation solutions. The theory of a “sanitation economy” is this: if they unlock previously unvalued assets in the waste system, they’ll build more sanitation infrastructure than governments would on their own. As the former TBC executive director, Cheryl Hicks, says, “to reach sanitation for all, we should focus on the value the systems can generate, not just the cost to deliver services.”35

The TBC is an accelerator of innovative, early-stage companies with waste-to-value technologies, such as smart toilets that capture data on resource flows. The multinationals in the partnership operate as advisers, customers, investors, and partners that can help the new companies ramp up. It may seem wrong to treat a human right as a business proposition, but it’s pragmatic: governments and communities lack the resources to fill the gap for billions of people. The fastest way to get sanitation technologies to scale is to turn waste into something valuable, and then leverage the power of business and markets. These approaches do not take value from poorer communities in the way extraction industries often do; they build permanent infrastructure that profoundly improves health and quality of life. It’s net positive in all dimensions.

The number of multistakeholder collaborations hoping to solve our largest problems is growing rapidly. Consider a few examples, especially in water, which is impossible to do right without all players in a watershed. These collaborations are worth keeping an eye on and learning from (whether they succeed or fail):

- The World Bank hosts the 2030 Water Resources Group, bringing big beverage companies such as AB InBev, Coca-Cola, Nestlé, PepsiCo, and Unilever together with civil society partners to develop regional and local water resource management strategies.

- Doug Baker, the executive chairman of Ecolab, started the Water Coalition to accelerate the UN-sponsored CEO Water Mandate. Members commit to water stewardship, transparency, and new goals that, Baker says, “mirror the science-based 1.5°C carbon goals.” In stressed watersheds, they will target a 50 percent reduction of water use by 2030 and a 100 percent reduction, or “renewal,” by 2050. Ecolab’s existing work with The Nature Conservancy proves, Baker says, that in watershed protection “you can make a huge difference without huge money.”36

- The Global Battery Alliance assembles seventy organizations across business, governments, UN agencies, NGOs, and knowledge partners to ensure that the massive carbon reductions the world needs from electric vehicles actually happen.

- The Getting to Zero Coalition connects big maritime shippers (such as Maersk), commodity and product manufacturers, banks, ports, and NGOs to reduce greenhouse gases from shipping by 50 percent by 2050.

What Net Positive Companies Do with Multistakeholder Groups

- Lead multistakeholder collaborations, inviting all the players that are needed, no matter how complicated it gets

- Look holistically at their operations and communities to find gaps and opportunities to improve well-being

- Explore innovative business and financing models to solve societal problems in new ways

Strength and Resilience in Numbers

There are more partnerships to choose from than ever before. It’s hard to know where to begin. We can say with confidence that a few key organizations are involved in the majority of efforts that have scale. Look to WBCSD, We Mean Business (or one of its member organizations, such as Ceres or the Climate Group), UN agencies like the UN Global Compact, or other multilateral organizations, such as the World Bank. It’s not a big risk to join multiple partnerships. It’s important not to spread yourself too thin, but you will know quickly if a group is action-oriented enough for you—or moving too quickly if you’re not ready yet.

These groups allow for leadership in a safer environment. Being half a step ahead of the parade, calling the cadence, can create advantage, but you don’t want to get too far ahead, or you might take all the heat for what doesn’t work perfectly. You can push boundaries more by working together. When you gather groups, people are braver, creating what Paul’s firm IMAGINE calls “courageous collectives.”

That’s one of the many benefits of these partnerships. In total, they create resilience for the members. Nothing can protect a company from all possible outcomes—after all, a pandemic was technically foreseeable, but was impossible for sectors like hospitality to fully prepare for. But working together means having allies, the proverbial boats to lash together to ride out the storms. And when seas are calm enough, the group can move fast toward net positive.