Relational Characteristics in Social Media

Brand Experiences, Exposure, Relevance of the Message, and Relevance of the Group

Relational characteristics serve as mediators between brand characteristics and community characteristics. The first step is creating a brand that is well promoted and perceived as high quality, competent, and reputable online. Next, brand managers should spend time enriching brand experiences, through social media exposure and relevant messages. This chapter defines each of these relational factors and discusses how they are interrelated, affect consumers, and are influenced by the brand manager online.

Brand Experiences

First and foremost, consumers must have experience with the brand initially before forming a desire to interact with a brand online.1 The binding factor in relationships between people and brands is emotion. Consumers connect with a brand if the feel affect associated with the brand. When consumers identify with a brand, they desire experiences with the brand and with other users of that brand. This is where social media becomes an ideal forum for building this interaction, which ultimately leads to brand community. Consumer identities can be tied with brands, in that brands contribute to an individual’s sense of self (and the identity they portray in various situations). Brand identification discussed in the next section leads one to take on the emotional process of developing identity through consumption experiences.2 In turn, these experiences drive consumers to seek relevant online reference groups and the brand becomes even more salient to the consumer, leading down the path of a stronger and more durable bond between consumer and brand.3 The following sections identify how brands foster these experiences and incrementally strengthen relationships with consumers.

Types of Social Media Exposure

Exposure can occur in forms varying from the standard status update on Facebook to a six-second video vignette on the social network Vine. The original goal of social media was for consumers to connect and communicate with friends and family. Social media includes advertising that is akin to traditional online advertising, brand interactions with consumers, and consumer-to-consumer endorsement of brands. There are key types of social media exposure brands can undertake in the hopes of fostering positive brand-to-consumer, consumer-to-brand, and consumer-to-consumer interactions on various social channels. These different types include: content sharing, implied endorsement, customer service interactions, video vignettes, location updates, and paid advertising. For the greatest generalizability of these concepts, the exposure types are grouped by type of communication, not by the specific social network.

Content Sharing

The most common exposure in social media is content shared by a brand on social media. With over 1.4 billion active users, Facebook currently has the greatest reach of any social media network. Content shared by brands on Facebook can include status updates, images, videos, and links to content on other social networks. Content with images or video can gain great traction, and the image below serves as an example. Samsung Mobile USA posted an image (Figure 3.1) demonstrating how to use its Galaxy Gear smart watch with the simple caption of “Behold the many faces of Galaxy Gear.”4

Figure 3.1 Galaxy Gear shares images of its smart watch

Figure 3.2 Coca-Cola responds to Mashable on Twitter

Even a simple execution such as this resulted in over 29,000 likes and over 1,600 shares. While Samsung Mobile USA has over 26 million fans on Facebook,5 the sharing of this post had extensive reach. This strategy is also prevalent on Twitter. Recent updates have allowed content such as images and videos to play in the browser or app window for more effective content. For example, Coca-Cola responded to new media blog Mashable about a recent article and included a visual image branded Coca-Cola, as shown in Figure 3.2.6

In addition, visual images are shared regularly via Instagram and Pinterest, and this content can be easily reshared to a network member’s audience. Icons for each of the major social networks typically appear below a participant’s post, and this mechanism is the ubiquitous method for syndicating content to a person’s other social networks. In 2015, Pinterest announced the launch of functionality to allow participants to buy products directly from the site, with 2 million products available at launch.7 This initiative allows consumers to easily buy products they like through consumer recommendation, and it augments Pinterest’s advertising revenue strategy.

Implied Endorsement

For each person who shares, likes, or comments on content shared by a brand, each member of his or her network has an opportunity to see this brand interaction through the Facebook Newsfeed. Additionally, in the right pane of Facebook, a live feed of friend activity (such as page likes, page interaction, music consumed, etc.) scrolls constantly, increasing the chance that a person’s network will see interactions with a brand page’s content. Potential reach of specific content is calculated using: (1) the number of social media users who like the page and (2) the total number of friends in network by users interacting with that content. Actual reach includes the actual number of brand fans who saw the content and the total number of friends of brand fans who saw their brand interaction through the newsfeed or other means. In Figure 3.3, the reach number of interactions includes likes, comments, and shares (respectively) on Facebook, but does not include the incidental exposure that comes from members of each of those participants’ networks.

A market maven is a thought leader related to product categories and marketplaces who shares product purchase and use advice.8 If a Facebook user is considered to be influential (i.e., a market maven), that user is likely to influence his or her network so that the network develops a more positive evaluation of the brand. Therefore, content shared can have a snowball effect, much like the sharing from the Galaxy Gear image. Brands want influential consumers to like and share the brand’s content so that they gain exposure to friends of their brand fans. Therefore, finding the best content and proper execution is critical. Creating compelling content that mavens want to share helps diffuse the brand message to a wider audience.

![]()

Figure 3.3 Social media platforms communicate message reach

Customer Service Interactions

Customer service exchanges between customers and service providers are a key type of social media interaction. As mentioned in the discussion on competence, consumers expect that brands will respond in social media channels. This is particularly true for customer service exchanges. Social media has a wide reach, including the consumer engaging with the brand, other consumers who access the brand’s social media page, and those customers’ networks. Effective, prompt, and positive customer service handling is critical in today’s world with social media exposure. Prior to the widespread adoption of social media, customer complaining was largely a private affair. The consumer would interact with the company via the call center, e-mail, website form, or slow mail. The complaining consumer might share complaints with others through traditional word-of-mouth communication; however, service interaction was typically between the consumer and the brand. Social media has shifted power from the firm to the consumer. When a consumer complains via social media by tweeting about a problem or posting dissatisfaction on a brand’s Facebook wall, the customer service interaction becomes a public exchange. Others’ opinions may be influenced by incidental exposure to social media interactions between the brand and another consumer. This voyeurism has the potential to change both opinions and preferences for these secondary consumers. Brands can benefit from the positive word of mouth on social media. Therefore, brands are wise to invest in ways to service social media complainers.

When brands interact with consumers and proactively try to resolve problems for the consumer, they signal to other social media users that all complaints will be handled in the same manner. Conversely, ignoring a social media complaint signals that the company would extend that same apathy to other consumers. In many cases, brands attempt to push the discussion off the social channel into another servicing method. In Figure 3.4, American Express’s @AskAmex Twitter account “follows” the customer so the communication can be conducted via private direct message. The representative invites the consumer to chat via AmericanExpress.com, which requires the consumer to log in and authenticate himself or herself. Pulling the consumer into the authenticated signed-in site allows the service agent to see account information, customer spending, and history with the brand.

Figure 3.4 Ask Amex communicates with consumers via direct message (DM)

This method for handling customer problems makes intuitive sense. The brand expresses concern and a desire to resolve the issue in the open channel, and then the conversation is taken offline. Another effective technique for pushing the discussion offline is to provide a contact for the service team handling social media, as opposed to the general customer service group. The public communication is that the social media team will handle the issue if the customer e-mails them. This signals to the consumer that the team he or she tweeted or posted to will investigate or handle the issue. Avis uses this approach with a dedicated e-mail to the service members of the social media team when a consumer complains via social media.9

A less effective method is to ask consumers to call the brand’s call center. If a consumer has previously not received resolution through other channels, then prompting him or her to use a previously unsuccessful channel will alienate the consumer. Often, if a consumer is tweeting the brand, he or she is in this exact scenario, having already attempted other channels without satisfactory resolution. Even a fast response can make the situation worse, particularly when the consumer is asked to call in.

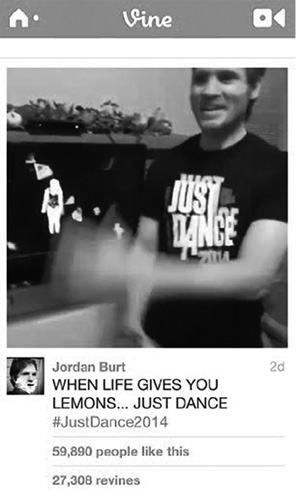

Video Vignettes

Gaining rapid adoption among social media users, Twitter’s owned Vine tool gained 12 million users in the first four months.10 Videos shot from mobile devices, either continuously or in stop motion, are shared on the Vine network and syndicated by users onto other networks such as Twitter and Facebook. Brands have found success in recruiting popular video contributors to create content that is likely to be shared and liked, such as the Just Dance video game promotion in Figure 3.5.11 In a mere six seconds, creative social media participants can create content that costs a fraction of the cost of traditional media and can gain significant sharing. Popular Vine contributors have earned up to $10,000 for their six-second videos and now have access to a talent agency that will broker out the Vine contributors’ services.12 Vine has quickly become an important element in social media.13

To compete with Twitter’s Vine offering, Facebook launched a similar feature on its visual network Instagram in 2013. The primary difference between Vine and the Instagram version is the length of the videos. In Instagram, videos may be up to 15 seconds.14 While these networks currently have limited reach, the ubiquitous share to Facebook and Twitter helps brands extend their reach (and any investment in content creation they make). Additionally, brands are exploring how to reach younger, mobile consumers via Snapchat, a social network that allows participants to share short videos or images that are finite in duration (or disappear after viewing). Brands exploring this platform include CNN, ESPN, People, Buzzfeed, and iHeartRadio. This service lists 60 percent of mobile users between 13 and 34 years of age as being Snapchat users, and over 4 billion video views consumed daily.15

Figure 3.5 Consumer-created video content

Location Updates

As recent as a decade ago, marketing scholars declared that the “place” component of the four Ps marketing mix was dead. These critics proclaimed that the global reach of the Internet made location irrelevant to marketing.16 With widespread adoption of mobile technology and deep integration of global positioning satellite functionality, location has regained significance.17 Today, status updates on most social media platforms can be tagged with locations, including Facebook statuses and tweets. Two closely related location-based social networks, Swarm and Foursquare, have integrated social updates with a person’s physical location. While at a store or restaurant location, participants can share their location with both users on both sites and their wider network (via Facebook, Twitter, or both). This content can be in the form of a “check-in,” which is essentially a status update showing where the person is located. Consumers can also share tips with their networks concerning what to do, what to buy, or what to expect so that other users may use the experience in their information search. Location-based social media platforms use crowdsourced information databases created by its users. Users create and update the locations on the social media platform. Rather than keep the database as a proprietary asset, Foursquare licenses its database to other apps, including Vine and Foodspotting. This allows the users to add to the content and share their experience with their network. Location sharing is available on mobile as well as on web-based updates made on a desktop or notebook computer. As of 2014, Swarm serves as the location check-in feature, and Foursquare serves as a source of location reviews, tips, and images. Users of either app are able to navigate seamlessly from one app to the other from check-in to consumption of reviews.

As with implied endorsement, location updates can signal user’s networks as to feelings toward a store or restaurant. Furthermore, this signal can influence the network, particularly when the user is influential within that network. If the participant is seen as influential in a product category, his or her tips or insights may be more powerful at influencing the network (as with the traditional market maven concept). Business owners can “claim” their Swarm page. This allows proprietors insight into the frequency of visitors, the most frequent visitor, and how visitors might be influencing others. Managers can access Foursquare’s business “dashboard,” where they can learn participants’ social media account information. Having the participants’ social media account information allows the business to recognize loyal customers with rewards and welcome first time visitors with specials and promotions. As brands seek to promote community formation, this type of two-way communication becomes essential. As network participants contribute tips and visual content, they further contribute to the online and mobile reputation discussed in Chapter 1.

Paid Advertising and Sponsored Content

Social media platforms have continuously sought ways to capitalize on the active user base, and a key element of this monetization has been advertising. On Facebook, primary forms of paid advertising include display ads (shown on the right side of the computer interface platform) and sponsored content or suggested pages. Display ads can be easily created using the online tools for page administrators. Ads may display on Facebook pages (to generate a like by nonfans), on a specific status update or content element (such as images or links to a brand’s website), or on event invites. One tactic Facebook leverages is showing a sampling of a participant’s network who likes a page to encourage others to join in “liking” the page. This tactic is related to the use of reference groups, examined in the next section. In Figure 3.6, Netflix shows a participant’s friend who likes the brand and presents a call to action leading to a website landing page promoting exclusive streaming video content.18

Sponsored content takes the form of a regular brand update on a person’s social network feed; however, sponsored content does not come from brands subscribed for by the user. In this case, the brand paid the social media platform for its content to appear in the feed. This approach is used by both Twitter (denoted as Promoted) and Facebook (denoted as Sponsored), as can be seen in Figures 3.6 and 3.7.

Figure 3.6 A member of your network “likes Netflix”

Figure 3.7 Twitter marks paid tweets as “promoted”

On Twitter, sponsored tweets appear toward the top of the Twitter stream and indicate sponsored content with an orange arrow, like this update from e-mail administrator Mailchimp.19

Twitter also allows sponsored user suggestions, which prompt participants to follow an account that has paid to be suggested, and Twitter sells access to its trending keywords.

Relevance of the Message

Research in traditional advertising has established the need to create and communicate a relevant message to the target consumer base. Social media communication requires the same level of relevance and consistency. As previously mentioned, brand messages and endorsements shared by reference groups (a group that an individual perceives to be similar to himself or herself) are also important in social media. Types of social media exposure that consumers encounter vary greatly and include status updates, paid advertising units, sponsored stories (advertising), implied endorsements, and location check-ins. In visual networks, such as Pinterest and Instagram, exposures include image sharing by users or resharing of another user’s images.

As with all forms of marketing communication, messages must be relevant to the intended audience. This tenet holds true in social media, where the goal is to foster a long-term relationship and ongoing two-way communication. If a brand’s message, including images, web links, consumer testimonials, and video content, is not relevant to consumers, then brand community cannot be fostered. Consumers can unsubscribe from a brand as easily as they originally followed the brand. It is critical for brands to closely monitor key social media metrics, such as new followers, unsubcribes, and (if available) the number of followers who muted or hid the brand from their feed. These measures provide a critical barometer for whether the message is on target and which posts generate the most activity. Engagement with posts, including sharing and endorsements (such as likes on Facebook or retweets on Twitter), provides further corroboration that the content created and shared by a brand is on target.

When a message is relevant and the delivery is passionate, that relevance leads to resonance, which can create mass influence. Social media tools offer new ways for brands to increase perceived relevance for consumers. The relevance of social media is the degree to which the media is perceived as identity relevant. Simply put, psychological research has shown that consumers foster and maintain a number of situational-specific identities, and media consumed can be shown to positively contribute to a person’s identity. A history of consuming identity-relevant media enables the consumer’s identity and provides behavioral evidence that informs self-attributions about identity importance. In the brand social network, live and authentic messages are important, and these messages must resonate with the target audience.

Relevance of the Reference Group

A reference group is any group of people that an individual identifies with and uses to form attitudes and guide behaviors. For college students, fellow students within the same major may serve as a reference group. For professionals, people in the same discipline, such as nursing, can serve as a reference group. In all cases, individuals look to their reference group for signals about appropriate behavior, attitudes, and values. The relevance of the reference group is an important factor when considering how social media interactions influence identification with other brand fans and the importance of the brand relationship to the consumer’s identity. In the social network, ties can range from weak to strong, and reference groups must be relevant in order to significantly influence behavior. If a social media exposure occurs with a friend or a member of a relevant reference group, the rate of identification will be higher than if the reference group is not relevant.20 This concept has been demonstrated with research showing that when consumers are shown rapid images with brand logos discreetly placed in context of the photo, brand choice was influenced by the logos presented. Half of the participants were shown images of individuals wearing clothing with brand logos likely to prime the participants for the reference group (college logo of their school). The other half were shown images of individuals wearing clothing with logos not likely to prime the reference group (college logo from a different school). Participants were more likely to choose brands shown when the images primed the participant’s reference group.21 When users of social media encounter a brand interaction, such as someone liking a page, commenting positively about a brand, or checking into a location and sharing this update, the observer is likely to judge the brand more favorably when they perceive the endorsers to be part of their reference group. Consumers are typically more favorable toward content endorsed by their perceived reference group.

While Facebook uses the nomenclature of “Friend,” the composition of an online social network, in reality, is a continuum that spans from strangers to acquaintances to lifelong friends to family. Early in Facebook’s history of display advertising, the newsfeed would show a brand’s ad with a list of friends who liked the brand. What Facebook did not consider was whether or not the user actually considered the endorsers part of their social network. In this scenario, if the user did not consider the network members chosen by Facebook to be part of his or her reference group, the user would not look as favorably upon the brand message as he or she would if the endorsers had been friends. This puts Facebook at risk for the undesirable consequences of negative brand associations.

Facebook has taken steps to improve its ability to predict the nature of the relationship between the individuals in the network and, thus, how endorsements of sponsored content and display ads affect others. When a Facebook member adds a new friend or accepts a friend request, Facebook now asks whether the member knows this person offline. This information contributes to Facebook’s repository on the relationship of the member for better online ad targeting. Also, Facebook tracks which members of a participant’s network are frequently engaged online with the participant (or conversely has muted or hidden). This information is appended to Facebook’s database of member relations, called Facebook Graph. Understanding the complex nature of online friendships allows Facebook to know who would qualify as a “frenemy” versus a “friend” and monitor weak ties versus strong ties. Facebook is able to present better brand-sponsored ads when the reference group is better defined.

The mobile social network Foursquare also uses the concept of the reference group when making location suggestions to users (Figure 3.8). Foursquare does not appear to maintain knowledge of the interactions between participants. This is most likely because as a location-sharing platform, it is highly unlikely that a user would allow frenemies, acquaintances, and strangers to know his or her location. A suggestion on Foursquare shows a thumbnail of a person in the user’s network that has visited a location and the frequency of visits. In Figure 3.8, five thumbnails are shown that indicate who in the network has visited that location. Hovering over a thumbnail on the web version of Foursquare shows the frequency.22

Consumers make judgments based on knowledge of congruency between their own preferences and those of their network. When users perceive parallels between their own tastes and those of contacts shown, a favorable evaluation is likely to occur. Further, recent academic research has found that relevance of the reference group impacts a consumer’s judgment of that brand on Facebook.23 This research indicates that hiding or revealing the demographic characteristics of a brand’s fans can positively or negatively influence evaluations of the brand by others. Thus, consumers are likely to make positive judgments when content is relevant and when the person generating the content is someone the user identifies with.

Figure 3.8 Foursquare’s use of the reference group

Case Study: Neiman Marcus

For a unique look into the strategic execution of social media, we look to upscale retailer Neiman Marcus.24 The retailer has pages for its main brand and individual pages for its specific stores, with the highest number of social media followers being on the Facebook page. Neiman Marcus’s main Facebook page had over 850,000 active users in 2015.25 However, primary interaction takes place on other networks. For example, the brand has earned over 82,000 followers on Pinterest,26 and each piece of visual content actually gets more engagement than posts on Facebook. Pinterest users can both endorse a visual image or “repin” it to their own profile’s boards. The brand curates a number of boards with the theme “The Art of.” Topics within this theme include “The Art of Giving,” “The Art of Words,” and “The Art of Black and White.” These boards highlight topics related to various categories of Neiman Marcus products.

With over 300,000 followers, the brand enjoys high per post engagement on Instagram.27 While the number of total followers is a fraction of that of Neiman Marcus’s Facebook followers, the total engagement per post is the highest of all of the networks on which the brand participates. Figure 3.9 contains a post featuring a merchandise window for the holiday season. This post received over 3,000 endorsements from Instagram users, which is far more successful than the fewer than 100 endorsements per Facebook post the brand receives.28

Figure 3.9 Neiman Marcus enjoys high interaction from consumers

Note that while the execution of the social media content may look seamless to the observer, creating social media content is quite multifaceted for a brand as complex as Neiman Marcus. With many locations throughout the United States, regional tastes and variations must be taken into account. The public relations group that directs social media activities for the brand has designed a well-planned strategy that allows various stores to create and contribute content for use across social media channels. Regular training on topics such as brand tone and appealing photos is provided to key contacts at stores so that consistency is possible. The result is a mix of text content and images that reflect the diverse fashions and trends available through the retail chain. The firm also takes a “test and learn” approach to the ever-changing social media landscape. Neiman Marcus was an early pioneer in mobile social networks, running early promotions with location network SCVNGR. They were also an early adopter of Vine, featuring six-second “sizzle” reels from New York Fashion Week. While Neiman Marcus is a massive operation with a niche, upscale audience, the retailer’s willingness to test and learn in an effort to find the optimal social media footprint (while sourcing content from each of its regions) is best practice. Had the brand stuck with social media exemplars Facebook and Twitter, they would have missed opportunities to exploit smaller social media platforms (i.e., Pinterest and Instagram) where they have engaged more consumers per post.

Figure 3.10 Neiman Marcus appeals to consumers via Pinterest

Key Takeaways

- Many types of brand exposure opportunities exist; some are generated by the brand, but the most powerful exposures come from peer-to-peer brand discussions.

- Consumers make judgments on both the relevance of the message about the brand and the people who associate themselves with the brand in social media, known as a reference group.

- Consumers weigh whether or not consumer-generated content comes from people like them or from someone not like them.

- Research shows that when advertising messages, including social media, show a reference group relevant to the observer, a more favorable judgment is likely to be elicited in the observer.

- While image- and video-based social networks such as Instagram, Vine, and Pinterest may be smaller than Facebook, their content can be spread through the larger networks. Brands must decide on an optimal social media footprint.

- Visual networks, like Instagram, Pinterest, and Vine, may result in higher referral traffic to e-commerce sites. While Facebook is a mandatory due to its critical mass of active users, more effort may be warranted on smaller networks.

- Monitoring return on investment through metrics such as referral traffic, sales conversions, and e-mail signups should serve as a barometer for where to focus efforts.

- Social media customer service is a mandatory; consumers expect that you will respond to them, and consumers observing the actions of a brand (or inaction) assume the brand will treat them the same in the future.

- Resolving a customer service issue in social media is more than asking them to call the call center; most likely they tried and gave up. Find ways to push them into a chat conversation, like @askamex does in their Card Center section of the website.

- Resolved issues can result in raving fans. Good word of mouth from resolved issues reinforces the brand’s story online.

- Test and learn. There is no one size fits all solution in social media. Try new content across various networks to see what engages brand fans effectively.

- Snapchat is a growing way to reach younger mobile users through video.