Target Valuation in Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions

So far we have discussed target company valuation methods within a country with value expressed in local currency units. However, cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As) involve foreign currencies and exchange rates. In this chapter, we will discuss exchange rates, cross-border valuation of cash flows, cross-border valuation of target companies, exchange rate determination, and related concepts and theories.

The Nominal Exchange Rate and Currency Transactions

A nominal exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another one. Foreign exchange or foreign currency transactions take place in foreign exchange markets. The foreign exchange market is an over-the-counter market, implying that there is no single physical location, such as the New York Stock Exchange, where traders meet to conduct business. The over-the-counter markets operate by means of electronic communication networks that link the participants, that is, the buyers and sellers of currencies. An overwhelming majority of foreign exchange transactions consist of the electronic transfer of funds from one account into another.

The Exchange Rate Quotation

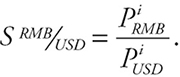

In the previous section, we defined a foreign exchange rate as the rate at which one currency is exchanged for another one. Accordingly, foreign exchange rates in various countries are defined in terms of the currency of the countries, just as the prices of different products are expressed in terms of monetary units of nations. In China, for example, the prices of commodities, services, and foreign currencies, with the latter as a special class of commodities, are set in Renminbi (RMB). Hence, an automobile may be priced at RMB200,000.00, a shirt may be worth RMB100, or a U.S. dollar is priced RMB6.25. When we price a foreign currency in terms of yuan, such as RMB6.25 = USD1, the quotation is given in Chinese term. If we quote the exchange rate between dollar and yuan such as USD0.16 = RMB1, we are quoting the currency in American term, that is, we are stating the dollar price of one unit of RMB.

When each unit of a foreign currency is quoted in terms of domestic currency, such as USD0.16 = RMB1, it is a direct quotation. When each unit of the domestic currency is expressed in terms of a foreign currency, that is, RMB6.25 = USD1, then it is an indirect quotation.

Indirect quotations are reciprocals of direct quotations. For an example of the yuan–dollar rate, we have

The currency exchange rates are quoted to four decimal places. The fourth decimal (0.001) is called a point. If a finer quotation is required, then the currency is quoted to the fifth decimal place (0.00001). The fifth decimal point is called pip.

Real Exchange Rate

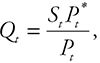

The definition of exchange rate provided thus far is nominal rate: It does not consider prices in the countries involved. The exchange rate that considers price levels is called the real exchange rate. Real exchange rate compares the value of the home country’s goods with the value of the same set of goods of another country. Stating it differently, it is the home currency’s purchasing power of foreign goods at the prevailing nominal exchange rate. The real exchange rate is different than the nominal exchange rate, with the latter being the home country’s nominal prices of foreign money. The real exchange rate for a currency, Qt, is calculated by the following formula:

(11.1)

(11.1)

where St is the number of home or domestic currency for a unit of foreign currency at time t,![]() is the foreign price index at time t, and Pt is the domestic price index at time t. Note that Qt expresses price of the domestic goods in terms of foreign goods. For example, we might say a basket of goods in Madison, Wisconsin is worth 250 yuans. Moreover, when one multiplies the nominal exchange rate, which is expressed as the number of domestic currency per unit of foreign currency, by a term that is expressed in units of foreign currency, the result is in units of domestic currency. Accordingly, the right-hand side of (11.1) implies the ratio of average foreign prices that is expressed in the domestic currency unit and the average price level, which is also based on domestic currency, making the average price levels in both countries directly comparable.

is the foreign price index at time t, and Pt is the domestic price index at time t. Note that Qt expresses price of the domestic goods in terms of foreign goods. For example, we might say a basket of goods in Madison, Wisconsin is worth 250 yuans. Moreover, when one multiplies the nominal exchange rate, which is expressed as the number of domestic currency per unit of foreign currency, by a term that is expressed in units of foreign currency, the result is in units of domestic currency. Accordingly, the right-hand side of (11.1) implies the ratio of average foreign prices that is expressed in the domestic currency unit and the average price level, which is also based on domestic currency, making the average price levels in both countries directly comparable.

Furthermore, note that, to make such a direct comparison of the price levels in the two countries meaningful, one should take care by including the same items in the construction of both indexes. For example, suppose we want to construct a true real exchange rate for RMB and dollar. Also, for simplicity, suppose we have only two items in our composite: MacDonald Value Meal and DVD. So, we would construct a price index for MacDonald hamburger, fries, soft drink, and DVD in China, and we do the same for these goods in America and then use the spot exchange rate to compute the real RMB–dollar exchange rate.

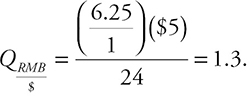

An example would clarify the concept of real exchange rate. Suppose we have three items in the basket: hamburger, French fries, and a soft drink. Furthermore, let the average price of the items in the basket in Beijing be RMB24, and in Madison, Wisconsin be USD5. Moreover, let the nominal RMB–dollar rate be RMB6.25 = USD1. Then using Formula (11.1) the real dollar–RMB exchange rate is calculated as follows:

and the real yuan–dollar exchange rate is calculated by:

How should these numbers be interpreted? According to the first equation, 0.768 U.S. basket is the equivalent of 1 Chinese basket, and according to the second number, 1.30 Chinese basket is equivalent to 1 U.S. basket.

Note that the real exchange rate is a measure of competitiveness of a country. If ![]() then foreign prices on average are higher than average domestic prices, making the domestic economy more competitive with respect to the foreign country. On the other hand, if

then foreign prices on average are higher than average domestic prices, making the domestic economy more competitive with respect to the foreign country. On the other hand, if ![]() then foreign prices are, on average, less than average domestic prices, making the foreign country more competitive. In the previous example of the basket of hamburger, fries, and soda, the U.S. price is lower than the Chinese price for the goods, giving the United States a competitive edge with respect to China in the supply of these products.

then foreign prices are, on average, less than average domestic prices, making the foreign country more competitive. In the previous example of the basket of hamburger, fries, and soda, the U.S. price is lower than the Chinese price for the goods, giving the United States a competitive edge with respect to China in the supply of these products.

The Law of One Price and Purchasing Power

The law of one price states that in the absence of transportation costs and tariffs or other restrictions on international trade, identical goods sold in different countries must have the same price when the prices are expressed in the same currency. Formally, this law can be expressed as follows:

![]() (11.2)

(11.2)

where ![]() is the yuan price of the i th item,

is the yuan price of the i th item, ![]() is the number of yuan per dollar, and

is the number of yuan per dollar, and ![]() is the dollar price of the ith item.

is the dollar price of the ith item.

For example, given RMB6.25 = $1, an item that sells for $20 in the United States should sell for RMB125 in China, if the law of one price prevails.

Using the formula for the law of one price we can rewrite the relationship as follows:

This equation says that the RMB–dollar exchange rate is determined by the ratio of the price of the item in China and the price of the item in the United States. Of course, this should not come as a surprise to anyone, since if the law of one price holds, this relationship must be valid. However, empirical verification of the law is a totally different, albeit challenging story.

The theory of purchasing power parity (PPP) is directly derived from the law of one price, and states that the exchange rate between two currencies equals the ratio of price levels in the countries. Note that the price level of a country reflects the domestic purchasing power of the currency and is the weighted average of a basket of goods and services. Accordingly, the theory predicts that a fall in the domestic currency’s purchasing power (a rise in the inflation rate, which is the same as an increase in the price level) leads to a proportional decline in the value of the currency in the country where price level has increased. Accordingly, domestic inflation and value of the national currency are inversely related: When the domestic price level increases, the number of foreign currency required to obtain the domestic currency decreases, which means foreign currency appreciates and domestic currency depreciates. Note that the percentages of appreciation and depreciation of the currencies differ.

Symbolically, therefore, we can express the absolute version of the PPP theory as follows:

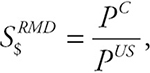

(11.3)

(11.3)

where PC is the RMB price of a basket of goods and services sold in China, and PUS is the dollar price of the same basket of the goods and services that are sold in the United States. For example, assuming we have a basket of identical goods in both United States and China, suppose that the RMB cost of the goods in China is RMB1000 and the cost of the same goods sold in the United States is $250; then PPP predicts that the RMB–dollar exchange rate is RMB4 = $1.

Note that the law of one price applies to the price of an individual item, while PPP involves the general price level, which is the weighted average of prices of all items in the basket.

Another formulation of PPP theory, known as relative PPP, states that the percentage change in the nominal exchange rate equals the difference between the inflation rates in the two countries. Symbolically, if we take the natural log of the formula for the absolute PPP, we come up with the relative PPP theory, that is:

![]() (11.4)

(11.4)

where the term on the left-hand side refers to the percentage change in the RMB–dollar rate, %∆P c is the inflation rate in China, and %∆PUS is the inflation rate in the United States.

As an example, suppose the inflation rate in China and the United States is 4 percent and 2 percent, respectively. Then the relative PPP model predicts that the yuan price of dollar will increase by 2 percent, that is, yuan depreciates 2 percent.

Exchange Rate Fluctuations

Exchange rates, especially floating rates tend to fluctuate minute by minute, hourly, and daily. The rate of change in exchange rates is called currency appreciation and currency depreciation. When more units of a domestic currency are needed to purchase one unit of a foreign currency, the domestic currency is said to have depreciated, and the foreign currency has appreciated. The latter implies that it takes fewer units of the foreign currency to purchase a unit of domestic currency.

The formula to calculate appreciation and depreciation of a foreign currency is given by:

(11.5)

(11.5)

where St is the nominal (spot) rate in the current period t, and St−1 is the spot rate in the previous period.

Example 11.1

Suppose that St and St−1 stand for RMB–dollar rate in the current period and the last period, respectively. Given St = 6.25 and St−1 = 6.5, then

This implies that RMB has appreci-

This implies that RMB has appreci-

ated 3.84 percent with respect to the dollar.

Example 11.2

Calculate the rate of dollar depreciation in the previous Example 11.1.

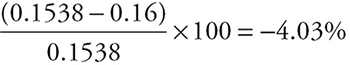

Note that the rates of appreciation and depreciation are not equal. To calculate the dollar depreciation, we must first express the dollar price of RMB, that is, we must express the exchange rate in American term. To do so, take the inverse of 6.25 and 6.5, that is,

This means that the

This means that the

dollar price of one RMB last period was $0.1538, and the price of one RMB this period is $0.16. Therefore, the rate of depreciation of dollar is

.

.

Spot, Forward, and Swap Currency Transactions

The preceding discussions that differentiate different concepts of the exchange rate are analytical concepts and have important policy applications; however, currency transactions never take place in terms of real or PPP rates. The actual currency transactions involve trading one currency for another one. Next, we will discuss how currencies are exchanged in reality.

Currency transactions take place in four ways: spot market transactions, forward transactions, futures transactions, and swap transactions. The spot transaction of a currency takes place when the deal is settled in two business days. The agreed date of payment is called the value date.

The forward contracts are private agreements between buyers and sellers relating to the exchange of a specific amount of one currency with another one at a specified exchange rate and a specific value date more than two business days. No money changes hands until the value date. The settlement date of a forward contract could be a few days, a week, several months, or even several years. The futures currency transactions are similar to the forward contracts; however, they are standardized contracts that are traded on an exchange. Futures currency contracts are settled daily by the exchanges. Finally, the currency swap transaction involves a related spot and forward transaction, where the forward transaction is to reverse the spot transaction.

Note that currency swap transaction as defined in previous paragraph is analogous to spot–forward transaction, which does not involve payment of interest. There exists another kind of currency swap, which involves interest payments on the outstanding currencies exchanged. The second type of currency swap is defined as “…a contractual agreement to exchange a principle amount of two currencies and, after a prearranged length of time, to give back the original principles. Interest payments in each currency also typically are swapped during the life of the agreement” (Butler 2004, 217). Often currency swaps are long-term agreements, the duration for which forward contracts do not exist. We provide the following example of currency swap.

Example 11.3: Currency Spot Transaction

A U.S.-based multinational company purchases $10 million RMB at the exchange rate of USD1 = RMB6.25. This implies that the multinational will deposit $10 million in the bank account of the seller of RMB and the buyer of the dollar will deposit RMB62,500,000 in the multinational’s bank account within two business days.

Example 11.4: Forward Contract Currency Transaction

On June 1, 2013, the foreign currency transaction desk of a multinational bank enters into a forward contract with German exporters of manufactured goods to sell ∈100,000 in exchange for Mexican pesos 1,622,847on September 1, 2013.

Example 11.5: Spot–Forward (Swap) Currency Transaction

The Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) requires 10 billion euros today. It contacts the European Union (EU) Central Bank for a swap transaction. The EU Central Bank agrees with the transaction.

The Fed buys 10 billion euros from the EU Central bank in the spot market, and locks in a specific exchange rate by signing a forward contract to sell 10 billion euros in one year.

Example 11.6: Currency Swap Transaction

We illustrate a currency swap with a fixed–fixed rate interest next.

Suppose Company A, a Chinese state owned enterprise, plans to acquire Company B in the state of Wisconsin, United States for $100 million. Even though it could borrow from a government-owned bank in China and covert the fund to dollars for investment in the United States, it prefers to swap currencies (RMB for dollar) with the Citigroup bank in Shanghai. Company A swaps RMB625,000,000 for $100,000,000 with Citi, that is, it deposits RMB625,000,000 in a Citi branch in Shanghai and Citi deposits $100,000,000 in Company A’s account in Chicago for 6 months. The swap agreement calls for 6-month London Interbank Rate (LIBOR) + 1.5 points variable rate on $100,000,000 to be paid by Company A to Citi and a fixed rate of 7 percent on RMB to be paid to Company A by Citi in Shanghai. This swap transaction is shown in the following chart:

The interest payments for the swap transaction appear in the next flowchart:

At the end of the swap agreement in 6 months, the swap transaction is reversed by Citigroup paying Company A, RMB625 million in Shanghai and Company A paying Citigroup $100 million in the United States.

The Relation Between Forward and Spot Rates

The relationship between the spot rate and the forward rate is defined by

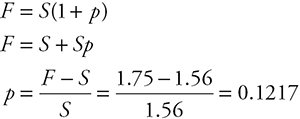

F = S(1 + p),(11.6)

Where F is the forward rate, S is the spot rate, and p is the forward premium.

Example 11.7

The spot dollar–euro rate is $1.56, and euro’s 180-day forward premium is 3 percent. Calculate the forward rate.

F = 1.56(1 + 0.03) = 1.6068.

Example 11.8

The dollar–pound spot and forward rates are $1.56 and $1.75, respectively. Calculate the forward premium.

Example 11.9

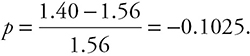

The dollar–pound spot and forward rates are $1.56 and $1.40, respectively. Calculate the discount rate.

Negative premium is called discount rate.

Cross-Border Valuation

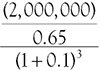

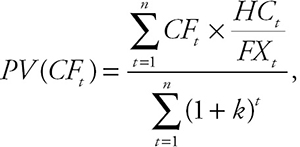

In the evaluation of target firms in cross-border M&As, the cash flow denominated in a foreign currency must be converted to the currency of the country of the acquiring enterprise. Therefore, exchange rate plays a prominent role in the valuations. This implies that the discounted value of future cash flows must be converted to the domestic currency units as follows:

(11.7)

(11.7)

where CFt is free cash flow in foreign currency units and  is the

is the

number of home currency HCt per unit of the foreign currency FXt, at time t, k is the discount rate, and t stands for time.

Example 11.10

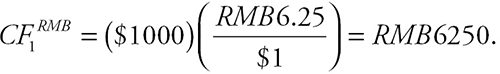

Suppose the cash flow from the first year of operation of a target company is CF1 = $1000. Suppose also that the exchange rate between RMB and U.S. dollar is USD1 = RMB6.25. What is the target’s cash flow in yuan for the year?

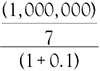

Example 11.11

A China-based multinational enterprise has operations in the United States, which are expected to last 3 years. It is expected that the cost of capital remains unchanged for the duration of the operations. The RMB–dollar exchange rates, the cost of capital, and the expected annual cash flows appear in the following table. Calculate the discounted cash flows in RMB units.

|

Year |

Cash flow in $ |

Exchange rate |

Cost of capital |

|

1 |

1,000,000 |

RMB6 = $1 |

0.1 |

|

2 |

1,500,000 |

RMB5 = $1 |

0.1 |

|

3 |

3,000,000 |

RMB4 = $1 |

0.1 |

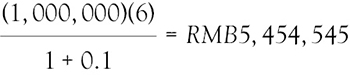

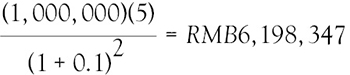

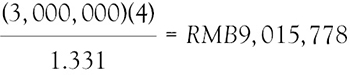

The ensuing table shows how the present value of discounted cash flows in RMB is calculated.

|

Year |

Discounted cash flow |

|

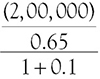

1 |

|

|

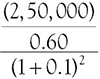

2 |

|

|

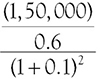

3 |

|

|

Sum of present values of cash flows in RMB |

RMB20,668,670 |

Note that in this example, because of the depreciating dollar, the value of annual cash flows in RMB would have been higher if the dollar was not depreciating.

Cash Flow Calculation in Multinational Operations in Multiple Currencies

The generalization of the prior discussion in converting cash flows denominated in a foreign currency to cash flows in multiple currencies is straightforward. To calculate the present value of discounted cash flows in multiple currencies, we use the following formula:

(11.8)

(11.8)

Example 11.12

A U.S.-based multinational corporation (MNC) has operations in three countries, which are expected to last 3 years. It is expected that the discount rate remains unchanged during the next 3 years. The values of the parameters and the excepted annual cash flows relating to operations appear in the following table. Calculate the value of the MNC’s cash flows in U.S. dollars.

|

Year |

China |

European Union |

United Kingdom |

||||||

|

|

Cash flow in RMB |

Exchange rate |

Cost of capital k |

Cash flow in euros |

Exchange rate |

k |

Cash flow in pounds |

Exchange rate |

k |

|

1 |

1,000,000 |

7 RMB/$ |

0.1 |

20,000 |

0.65/$ |

0.1 |

10,000 |

0.51/$ |

0.1 |

|

2 |

1,500,000 |

6 RMB/$ |

0.1 |

250,000 |

0.60/$ |

0.1 |

150,000 |

0.60/$ |

0.1 |

|

3 |

2,000,000 |

5 RMB/$ |

0.1 |

300,000 |

0.50/$ |

0.1 |

200,000 |

0.65/$ |

0.1 |

Solution

|

Year |

China |

European Union |

United Kingdom |

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

3

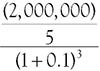

|

|

|

|

|

Sum |

USD637,007.61. |

USD1,074,861.76 |

USD619,603.53 |

|

Valuation: USD2.331,472.9 |

|

|

|

The last two examples demonstrate the effect of exchange rate variation on cash flows of a multinational enterprise. This is called exchange rate risk exposure. In the next section, we discuss different types of exchange rate exposure and review some remedies to mitigate such risks.

Foreign Exchange Risk Exposure and Mitigation

Foreign exchange or currency risk refers to the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on the performance of an enterprise. There are three kinds of exchange rate risk exposure: transaction exposure, economic exposure, and translation exposure. We discuss these risks in turn.

Transaction Exposure

Transaction exposure refers to the impacts of exchange rate fluctuations on a firm’s contractual transactions such as accounts payable and accounts receivable.

Economic Exposure

Economic exposure refers to potential changes in future cash flows resulting from unexpected changes in the exchange rate. For example, foreign currency depreciation impacts exports of an exporting company. Foreign currency appreciation affects imports of an importing company. When a foreign currency depreciates with respect to an exporting company’s home currency, the foreign buyers must pay a higher sum of the local currency to import from the exporting company. This tends to reduce the demand for exporters’ products. On the other hand, if the foreign currency appreciates (home currency depreciates), the exporting firm must pay a higher sum for its imports and it will have a negative impact on its cash flows.

Translation Exposure

Translational companies consolidate their subsidiaries’ financial statements for accounting and tax purposes. Subsidiaries in different countries keep their accounting books in local currency. In the process of consolidation, all accounts denominated in foreign currencies must be converted into the currency unit of the parent company. Because of currency fluctuation, these translations of accounts could adversely impact the cash flows.

A number of methods are used in hedging against foreign exchange risk exposure. These methods include entering into currency forward contract, using currency options, using money market, and swap agreement. Detailed discussions of these methods are beyond the scope of this book. We refer the interested reader to Chapters 11 and 12 of Madura (2008).

Summary

This chapter dealt with the valuation of target companies in cross-border M&As. The discussions dealt with nominal and real exchange rates as well as types of currency transactions such as spot, forward (futures), and swap. Moreover, both absolute and relative PPP theorems were discussed. Also, the relationship between forward and spot exchanged rates was examined. Additionally, cross-border valuation formula and cash flow calculation in multinational operations were used in example data. Finally, different exchange rate risk exposures were reviewed.