Selecting a Potential Target Company for Acquisition

As was discussed in Chapter 4, the search for and screening of a potential target candidate require applying a set of criteria such as the industry of the target firm and size of the deal. Of course, the size of the transaction is determined by the price of the target company.

Specifically, selecting a target company for mergers and acquisitions (M&As) involves implementing the following tasks.

Identifying and Understanding the Industry of Target Company

In goal-oriented acquisitions, which seek to fulfill the strategic plan of the acquiring firm, identification of the industry for acquisition has already taken place by formulating the strategy.

To understand an industry, however, one should have knowledge of the competitors and degree of competition in the market. A popular method of measuring degree of concentration in industries is Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI).

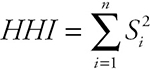

HHI measures the degree of competition in an industry and is the sum of squares of market shares of the firms in an industry. Formally, we express HHI as follows:

where Si denotes the market share of the ith firm in the industry, and n is the number of firms in the industry.

We use an example to illustrate the meaning of HHI. Suppose an industry is dominated by a single seller, that is, the company is a monopoly. This implies that the monopoly has 100 percent of the industry’s sales. Using the HHI formula we have ![]() This means that degree of concentration in the industry is 100 percent, or there is no competition in the industry.

This means that degree of concentration in the industry is 100 percent, or there is no competition in the industry.

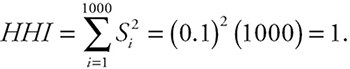

Now suppose the industry consists of 100 firms and each firm has 1 percent of the total sales of the market. Again using the HHI formula we have

This number is the lower bound of concentration measure in this example and implies no concentration. Therefore, the value of HHI in this example falls in the interval 100 ≤ HHI ≤ 10,000. Note that in an industry with 1000 firms where each firm has one tenth of the market share,

This implies that the maximum upper bound for the index cannot exceed 10,000, the lower bound does not assume a fixed number and varieties according to the market shares and number of the firms in the industry. In general, the higher the value of HHI, the higher the degree of concentration in the industry.

Assessing the Market Size and Growth Potential

Market share refers to the company’s total sales as a percentage of total sales by all companies in the industry. One could purchase market share data from vendors such as Market Share Reporter, Global Market Information Database, and Mintel Market Research Reports.

Of course, having some measure of concentration in an industry is useful in knowing the competitors in the industry and assessing the potential for growth based on reality of the market. For example, an acquirer might merge with a target to achieve economies of scale and increase its market power in an industry with a large number of competitors and firms with little market power.1

Appraising the Technological Changes and Trends in the Industry

Appraising technological changes requires an intimate knowledge of the prevailing technologies in the industry. The task must be performed by employees with technical expertise in the technological fields. It is argued that one reason for the development of research and development (R&D) departments by large companies is monitoring technological opportunities and threats faced by them (Mowery 1990).

Identifying Barriers to Entry in the Industry

Barriers to entry into an industry could be formidable in industries with low competition. Barriers to entry include economies of scale, patents, copyrights, licenses, control of inputs, brand royalties, and high cost for consumers to change their supplier. The barriers to entry should be identified during the selection process.

After the selection of an industry based on the aforementioned factors, a preliminary research for identification of a target company in the industry must be conducted. This task requires that the acquiring company develop the acquisition candidate pool.

Developing the Acquisition Candidate Pool

This step of the process should be based on the following:

•Assessing competitive position of the firms within the selected industry:

As discussed previously, one could use HHI in assessing degree of competition in the industry of the target firm.

•Estimation of revenue and size of the firms:

One could use annual revenues, asset value, or number of employees of the target in determining the size of the firm.

•Market capitalization:

Market capitalization refers to the total value of a company’s outstanding shares. Of course, the value varies according to the price of the stocks.

•Location of operations:

Location of operations especially in cross-border acquisitions should be identified.

Target Screening Process

The target screening process involves developing target profiles, defining screening criteria, and prioritizing targets. We discuss these tasks next.

Developing Target Profiles

In developing profiles of the target companies, one should keep the following considerations in mind:

•Business strategy (What is the target company’s business strategy?)

•List of products sold by the target

•Major news about the firm

•Customer data

•Target firm’s consolidated financial data

•Regional and international performance data of the target firm

•Cultural assessment

•Organizational assessment

•Integration options: absorb, maintain separate identity or operations, and partially absorb

•List of subsidiaries, affiliates, properties, directors, and executives

•Based on these considerations, select a number of target candidates from the larger list of target companies.

Defining Screening Criteria

The criteria used for screening should be based on the M&A strategic plan, financial plan, budget, and resource requirements, and should include the following items:

•Affordable price range (how much the acquirer can afford to invest in purchasing the target)

•Target size preference (determine the size of the potential target by market capitalization, revenues, net asset value, and so on)

•Profitability requirements (estimate earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization [EBITDA or EBIT], net margin, and free cash flow requirements)

•Determine the desired level of control over the target

•State preference for transaction structure (acquisition of shares vs. assets and acquisition vehicle inside or outside of acquiring company’s home country)

•Management requirements (decide on leadership style, expertise needs, receptivity to change, compatibility of culture, and model of postmerger management)

•Define marketing factors such as product lines, customer base, brand reputation, geographic presence, and distribution channels

•Identify R&D requirements such as licenses, patents, R&D centers, and investment

•Examine production requirements such as facilities, labor supply, production methods, and capacity

Prioritizing the Targets

After screening the targets they should be ranked so that the highest ranked firm is approached for acquisition or merger talks.

Financial Assessment of the Acquiring Company

After identification of a target industry or firm, the acquiring company should evaluate its own value before further pursuit of the target. The self-financial assessment enables the acquiring firm to determine its own financial strength and learn whether it has the capacity to absorb another entity. The acquiring company should assess its working capital and capital investment requirements through cash flow projection.

The following important questions must be answered.

1.What is the total financing requirement of acquiring the target and continuing future operations?

2.Will the cash flow generated by the company pay interest and principal of loan for financing the acquisition?

To answer these questions, we first need to define several terms.

Cash Flow Statement

A statement of cash flows is a financial statement that shows how changes in balance sheet accounts and income affect cash and cash equivalents, and breaks the analysis down to operating, investing, and financing activities (Wikipedia 2014).

Operating Activities Cash Flow

Operating activities cash flow emerges from payment of expenses relating to production, sales, and delivery of products to customer activities as well as collection of payments from the customers.

Investing Activities Cash Flow

Cash flow from investing activities emerges from purchase or sale of a real or financial asset, for example, land, building, machinery, and financial securities.

Financing Activities Cash Flow

Financing activities cash flow emerges from inflow of cash from investors, banks, shareholders, and outflow of cash to shareholders, and interest payment.

Example: A company acquires a target firm. The postmerger financial statements show the following cash flows:

•Sales revenues: $25,000

•Cost of goods sold: $12,000

•Net interest payment: $2,000

•Dividends: $500

•Cost of assets acquired: $8,000

•Wages and salaries: $7,000

A cash flow statement for this company is given in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Statement of cash flow: January 1, 2012–December 30, 2012

|

Cash flow from operations |

25,000 - (12,000 + 7,000) = $6,000 |

|

Cash flow from investing activities |

($8,000) |

|

Cash flow from financing activities |

($2,000+500) |

|

Net cash flow |

($4,500) |

Problem 5.1

Company XYZ has the following cash flow activities during 2012:

Net cash flow from operating Activities: $194,000

Investing activities:

Land purchase: $70,000

Building purchase: $200,000

Equipment purchase: $68,000

Financing activities:

Dividend payment to shareholders: $18,000

Issuance of bonds payable: $150,000

Prepare a cash flow statement for the company.

Due Diligence

After identification of the target firm, due diligence activities should take place. As discussed before, due diligence refers to processes in M&As with the aim of assessing the potential risks of proposed transactions by close examination of the past, present, and future (so long as the prediction of future is possible) of the target enterprise. The objectives of comprehensive due diligence are said to be “…an objective examination of the target company’s financial stability and adequacy of its cash flow, its products and services, the way that the company makes and losses money, the future market, its competitive position, and management’s ability to meet strategic objectives. Due diligence should be a comprehensive analysis of the target company’s business—its strengths and weaknesses—its strategic and competitive position within its industry” (Angwin 2001, 35).

It is a useful to start due diligence activities by preparing a preliminary information request list. A preliminary information request list follows:

•What are the issues identified in a preliminary assessment of the target?

•What is the financial position of the target enterprise?

•What is known about the background of the potential target firm’s management team?

•What is the reputation of the potential target company?

•Are the financial conditions and track record of the potential target firm consistent with the acquiring company’s tolerance for risk?

•What is the impact of the regulatory environment on the target firm’s future operations?

Often, certain issues arise in due diligence information gathering processes. Some of the typical issues are listed as follows:

•Potential targets are unwilling to supply the requested information for due diligence review.

•Financial statements may be ambiguous or inaccurate due to different accounting principles used in preparing them.

•Much of due diligence information may not exist or may not be available.

•Differences in valuation methods could pose difficulties.

•Nontransferable assets such as licenses may be held by the target company.

Types of Due Diligence

As stated previously, the aim of due diligence processes is to gain an understanding of strength and weaknesses of the target enterprise. In general, due diligence involves two stages: the preliminary stage and the full stage. Full diligence is conducted only after preliminary due diligence warrants further exploration in the processes of acquiring the target firm. Full diligence, sometimes called confirmatory due diligence, is often outsourced to professional firms such as consulting companies or law firms specializing in M&As after the terms of acquisition have been agreed upon. Due to its specialized activities, full due diligence may be divided into financial, legal, market, technology, and personnel categories. We discuss each of these due diligences next.

Financial Due Diligence

In financial due diligence, accountants take the responsibility of compiling and analyzing the financial data that are supplied by the target firm. The analyses of the data enable the acquiring firm to gain an understanding of the financial conditions of the target company. Furthermore, the accounting analyses would reveal the customer base of the target firm, the main suppliers of the materials to the target, the time frame of the accounts receivable and payable, the risks associated with acquiring the target, the turnover rate of staff, and tax liabilities. Financial due diligence takes the financial data provided by the target to be true, and does not make any statements about the validity of the report it produces, which is based on the data provided by the target firm. The task of validating the data supplied by the target firm is in the purview of an audit firm. However, auditing the target firm is substantially costlier than financial due diligence and takes a much longer time to perform compared to financial due diligence.2

Legal Due Diligence

Legal due diligence involves verification of the legal status of the target, validation of licenses held by the target, enumeration and verification of the target’s liabilities and assets, and identification of owners of target company’s assets. Furthermore, the entity or team conducting legal due diligence advises the acquiring company the legal and business risks of the liabilities of the target. Legal due diligence is often performed by professional law firms or attorneys. To illustrate the potential costs associated with inadequate legal due diligence, we examine the case of Ralls Corporation, a Chinese enterprise, which acquired a wind farms company in the state of Oregon, United States, next.

Case Study: Ralls Corporation and Acquisition of Terna Corporation

In March 2012, Ralls Corporation, a subsidiary of Sany Group, a Chinese company that manufactures wind energy conversion turbines, acquired four wind farms called Butter Creek Projects from Terna Energy USA Holding Corporation (Terna), a Greek company, in the state of Oregon.

In September 2012, U.S. President Barack Obama ordered the Ralls Corporation to divest the wind farm investment, located 200 miles from U.S. Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Oregon, which Ralls Corporation had acquired in March of the same year (Schlossberg and Laciak 2013).

President Obama’s order of divestiture was based on Exon-Florio amendment to the Defense Production Act of 1950 (DPA), which gives the president of the United States the authority to manage domestic industry in the interest of national defense. Title VII, subsection (d) states that “…the President may take such action for such time as the President considers appropriate to suspend or prohibit any covered transaction that threatens to impair the national security of the United States.” Furthermore, subsection (e) of the DPA reads “the actions of the President under paragraph (1) of subsection (d) and the findings of the President under paragraph (4) of subsection (d) shall not be subject to judicial review.” Subsection (f) of the law gives the President the authority to review the national security implications of foreign direct investments or foreign acquisitions of firms inside the United States by stating that “Factors to be considered for purposes of this section, the President or the President’s designee may, taking into account the requirements of national security, consider—….the control of domestic industries and commercial activity by foreign citizens as it affects the capability and capacity of the United States to meet the requirements of national security” (The Defense Production Act of 1950, as Amended 2009, 44–45).

Additionally, the DPA stipulates that “The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), established pursuant to Executive Order No. 11858, shall be a multi-agency committee to carry out this section and such other assignments as the President may designate” (The Defense Production Act of 1950, as Amended 2009, 48). The CFIUS is a multiagency committee and is chaired by the U.S. Secretary of Treasury.

The legal problems of Ralls Corporation started with inadequate legal due diligence before its acquisition in Oregon. Having observed the operations of similar foreign-owned green energy companies in the same areas, Ralls and Terna did not notify the U.S. government authorities about the acquisition, believing that they have met all the national security concerns of the U.S. Naval Air Station regarding the restricted airspace of the naval station.

After closing the deal, and 2 months after start of the construction activities, Ralls was notified by the CFIUS, a government agency that oversees foreign investment in the United States, that they should stop construction activities until completion of the investigation of the Ralls energy project. Ralls, however, ignored the notification, having confidence that they have met all the necessary national security requirements of the U.S. government, and further knowing that Sino-American cooperation on green energy development was agreed upon by President Barack Obama and the president of China at the time, Hu Jintao.

On July 25, 2012, CFIUS ordered Ralls to cease all construction and operation activities at the wind farms. Furthermore, CFIUS prohibited all access to the project sites with the exception of those U.S. citizens who were authorized to enter the site by the committee. Ralls Corporation complied and stopped all activities at the sites.

On August 2, 2012, the July order was amended by CFIUS prohibiting Ralls from selling or transferring any products manufactured by Sany to any third party for use at the project sites. Moreover the August order instructed Ralls to avoid selling the acquired company without first obtaining permission from CFIUS to do so.

President Obama’s September order of divestiture stated that because of existence of “credible evidence,” Ralls “through exercising control might take action that threatens to impair the national security of the United States” (Feldman and Burke 2013). The order gave Ralls 90 days to divest and 14 days to remove all structures and objects from the sites.

On September 12, 2012, Ralls Corporation filed a lawsuit against CFIUS and Timothy Geithner, the then secretary of Treasury, and subsequently amended the lawsuit to include President Obama’s order for “unconstitutionally taking property” without due process of law stating that “CFIUS’s powers under Section 721 and related executive orders and regulations are limited. It may only review certain ‘covered transactions’ that could result in foreign control of a person engaged in interstate commerce in the United States. It may not bar a covered transaction from taking place. And, like all agencies, it may not arbitrarily or capriciously render determinations absent any evidence or explanation or by unexpectedly and inexplicably abandoning a prior position or policy, and it may not engage in the unconstitutional deprivation of property absent due process.” Moreover the lawsuit claimed that “CFIUS violated the foregoing principles and well-established law when it issued an order subjecting plaintiff Ralls Corporation to draconian obligations in connection with Ralls’s acquisition of four small Oregon companies, whose assets consisted solely of windfarm development rights, including land rights to construct the windfarms, power purchase agreements, and necessary government permits. Without identifying any evidence or providing any explanation, CFIUS concluded that the acquisition was a ‘covered transaction’ subject to its authority and that ‘there are national security risks to the United States that arise as a result of’ the acquisition. Moreover, rather than propose measures that would have mitigated the purported (yet unidentified) national security risks, CFIUS—again without any evidence or explanation—instead required Ralls immediately to cease all construction and operations and remove all items from the relevant properties; prohibited Ralls from having any access to the properties; and forbade Ralls from selling the properties until all items had been removed, CFIUS was notified of the buyer, and CFIUS did not object to the buyer. CFIUS asserted that these obligations were enforceable via injunctive relief, civil penalties, and criminal penalties” (Ralls Corporation v. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States Document 1 2012, 2).

On February 26, 2013, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, where the Ralls Corporation lawsuit was filed, issued a ruling dismissing Ralls’s claims pertaining to the presidential statutory authority to order divestitures, but allowing further judicial review of the claim of unconstitutional violation of property rights of the plaintiffs without due process of law. Citing the defendants’ argument that the courts have no jurisdiction to hear cases involving a presidential order according to DPA of 1950, the district court ruled that “The statute is not the least bit ambiguous about the role of the courts: ‘The actions of the President... and the findings of the President... shall not be subject to judicial review’ 50 U.S.C. app. § 2170(e). Nonetheless, Ralls asks the Court to find that the President exceeded his statutory authority in imposing the conditions in the order, and that he acted in violation of the Constitution by treating these foreign owners of wind farms differently than foreign owners of other wind farms. This artful legal packaging cannot alter the fact that what plaintiff is urging the Court to do is assess the President’s findings on the merits, and that it cannot do. Since the finality provision bars review of the ultra vires and equal protection challenges to the President’s order, the Court will dismiss those claims for lack of jurisdiction. But plaintiff has also brought a due process claim that raises purely legal questions about the process that was followed in implementing the statute, and that claim will stand. The Court notes that it is not ruling that the due process claim has merit—simply that it is bound to go on to decide the claim on its merits. The Court will reach that question after further briefing by the parties” (Ralls Corporation v. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States Document 48 2013, 2).

On October 10, 2013, the U.S. District Court Judge ruled on the plaintiffs’ claim of failure of the president to follow due process of law in issuing the order to divest, by stating that “Defendants have now filed a motion to dismiss the remaining claim, and that motion has been fully briefed by the parties. Because Ralls has not alleged that it was deprived of a protected interest and because, even if the Court were to find a protected interest, Ralls received sufficient process before the deprivation took place, the Court will grant defendants’ motion to dismiss” (Ralls Corporation v. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States Document 58 2013, 2). The ruling was very specific in its reasoning for rejection of Ralls’s claim, by stating that “Ralls had the ability to obtain a determination about whether the transaction would have been prohibited before it acquired the property rights allegedly at stake, but it chose not to avail itself of that opportunity, Ralls cannot predicate a due process claim now on the state law rights it acquired when it went ahead and assumed that risk” (Ralls Corporation v. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States Document 58 2013, 8).

Ralls Corporation has appealed both the February and October decisions.

This case is an excellent example that illustrates the dire financial consequences of inadequate legal due diligence, especially in cross-border M&A transactions.

Market Due Diligence

By market due diligence activities, the acquiring company aims to understand the market position, market share, and marketing capability of the target company. The marketing due diligence team usually comprises members from sales, R&D, procurement, and technology areas of the acquiring firm.

Technical Due Diligence

Technical due diligence assumes importance for acquisition of the target company with advanced technology such as information technology, advanced manufacturing, engineering, and emerging technologies. If the acquiring company has expertise in the same technological areas of the target firm an in-house team can conduct due diligence. In cases where the target and acquiring companies have vastly different technologies and operate in different technological fields, outsourcing of technological due diligence and hiring a technology consulting firm are required.

Personnel Due Diligence

The acquiring company aims to gain an understanding of how the key managers and major shareholders of the target company arrived at their current standing through personnel due diligence. The issues of interest in personnel due diligence are determining the educational backgrounds, criminal backgrounds, family relationships, and civil litigation involvements of top executives of the target company. Personnel due diligence is often outsourced and professional background check organizations are employed for preparation of the personnel due diligence report.

Cultural Due Diligence

Culture is an important determinant of organizational effectiveness, especially during organizational transitions that are associated with M&A. Organizational culture plays a pivotal role in acquisition by exercising profound influence on coordination and control functions during postacquisition integration (Pablo 1994). Reducing cultural differences, both organizational, in cases of domestic acquisitions, and societal in cross-border ones can enhance organizational stability. Accordingly, cultural due diligence in the early stages of acquisitions has dramatic effects on their outcome.

It should be noted that before conduct of due diligence, a term sheet be prepared.3 A term sheet is a memorandum of understanding between the parties that are engaged in cross-border M&A discussions. It stipulates major terms such as valuation of the target, financing mechanism, and other related issues of the business transaction that is to take place. The absence of such a memorandum of understanding between the target and the acquiring firm could result in wasteful expenditure of a large sum of money and substantial time in due diligence and other negotiation activities that are doomed to fail in reaching an agreement.

A term sheet is different than a legal agreement for investment or a sale agreement. The term sheet differs from the latter two agreements for three reasons. First, a term sheet is legally nonbinding. The terms of the initial agreement are subject to change during the negotiation processes as more information becomes available to both parties. Second, a term sheet is written by the financial adviser or the negotiation team in simple language and not by a lawyer in a technical legal format. Third, a term sheet is valid for a specific period, for example, a few weeks, a month, or two months. After expiration of the term sheet, the parties are allowed to negotiate with other interested parties or agree on a new set of terms.

It should be noted that poor planning and inadequate due diligence of governmental policies of the host country, particularly inadequate due diligence in environmental policies and labor market conditions of the host country, could pose major obstacles for successful integration.

To illustrate potential challenges inadequate cross-border acquisitions of enterprises may pose, we cite the example of the China International Trust and Investment Company (CITIC) acquisition of Sino Iron, a multibillion dollar company in the business of extraction of magnetite iron ore in Western Australia.

Case Study: CITIC Group and Investment in Australian Mines

In 2007, CITIC Pacific, a subsidiary of CITIC Group, which is a state-owned financial services enterprise, purchased a mining license to extract two billion tons of magnetite iron ores for 25 years in an isolated region in Western Australia. The mining project was the largest cross-border mining investment of its kind by a Chinese enterprise with 100 percent Chinese ownership.

In October 2008, CITIC Pacific announced a loss of 14.7 billion Hong Kong dollars (roughly $1.9 billion) due to investment in forward contracts to hedge against currency fluctuation. In addition to 1.6 billion Australian dollar initial investment, the operations required an annual investment of at least 1 billion Australian dollars for 25 years of the mining operations.

Initially, CITIC Pacific was to invest $4.2 billion with the starting date of mining operations in the first half of 2009. However, due to a number of setbacks the required investment increased to $5.2 billion and its operations were postponed to early 2011. To prevent CITIC Pacific from bankruptcy, CITIC, the parent company, had to inject $1.5 billion into CITIC Pacific.

What factors contributed to the ill-planned Chinese greenfield investment project in Australia? There were many factors that contributed to the unpleasant situation for CITIC Pacific. These included labor issues; Australian nationalism; a hostile attitude toward Chinese investment in Australia; global oligopolistic control of the iron mining industry by two large mining firms—namely BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto; government regulations pertaining to environmental protection and tax policies; as well as the required large investment in infrastructure such as investment in construction of piers, ports, water and electricity plants, telecommunications, and roads in the barren region where the mines were located.

As an example of labor issues, which emerged because of cultural differences between Chinese and Australians, we note Chinese executives’ complaint about the work habits of CITIC Pacific’s Australian employees. The Chinese executives of Sino Iron found that “Despite the urgent situation…the local managers still left work at the regular time, took vacations, and expected a bonus at the end of the year. Sometimes engineers would be in the middle of processing concrete when it was time for them to leave, without worrying whether this would cause problems. When there were problems, employees would try to blame each other, and the sense of belonging and loyalty from Chinese firms was nowhere to be found” (Sun et al. 2013, 316).

CITIC Pacific problems were not confined to Australian workers’ attitude toward work. Australian nationalism created resentment among many Australian employees of the company. Some workers reasoned that since the company’s money belonged to the Chinese government, they need not care for the welfare of the company that has employed them. Moreover, the Australian government had also increased taxes and began regulation of cross-border M&A in Australia. For example, the Australian government announced a 40 percent resource tax on mining firms starting in July 2012.

The Australian environmental protection regulations were costly, and they were stumbling blocks too. For example, per Australian environmental laws the CITIC Pacific “…had monitored the underground water, animals in caves, sea turtles and birds on land, and audited the environmental performance of its contractors in order to ensure the protection of the natural environment” (Sun et al. 2013, 320).

In addition to labor relations, labor costs were also issues. Because of the remote location of mining operations, many mine workers had to come from big Australian cities. High demand and limited supply of labor had pushed the annual salary of an average mine worker to over 100,000 Australian dollars, a sum that is twice as large as the average annual income in Australia or at a level of annual income earned by professors in Australia. Moreover, some workers could take 1 week off for every 3 weeks of work or some workers took 2 weeks off. The workers required the company to pay their airfare so that during their break, they could fly to their homes.

To deal with the high labor cost, the CITIC Pacific management decided to bring in Chinese workers who would perform the same kinds of labor at substantially lower wages to Australia. However, the Australian government refused to issue visa for Chinese workers, requiring that the applicants for work visa to Australia must have a certificate showing their high proficiency in English language (Sun et al. 2013).

This case study clearly demonstrates that without foresight and adequate planning, cross-border investment, either in greenfield form, as was the aforementioned case, or in M&A transaction could face major obstacles in achieving the goals of the acquisition.

Summary

This chapter dealt with target selection processes for M&A. It discussed steps involved in acquisition of candidates and developing target profiles, and defined screening criteria and examined varieties of due diligence: financial, legal, market, technical, personnel, and cultural. As part of target selection, the cash flow statement analysis of a target firm was discussed. Moreover, to illustrate the detrimental effects of inadequate due diligence, two case studies involving a Chinese acquisition in the United States and a greenfield investment in Australia were presented.