CHAPTER 6

Preparing for Delivery

We were in San Francisco on the top floor of our corporate headquarters in the boardroom, admiring the breathtaking view of the bridge and the bay. It was late afternoon. Our executive team was there to rehearse our division’s annual business review presentation for the CEO and his direct reports early the next morning. We all felt somewhat intimidated by the surroundings—a deep plush carpet, a walnut conference table big enough to serve as an airplane runway, and a hushed silence in the hallways. The digital projector was state-of-the-art for the time, mounted in the ceiling, and focused on a giant wall-screen. However, when we hooked up our laptop and projected our PowerPoint deck, something was wrong—the colors didn’t translate properly; greens turned a funny yellow, and reds looked muddy brown.

None of us being techies, we fussed with our laptop settings for a while to no avail; one of our team even took his shoes off and climbed on the massive table to punch a few buttons on the ceiling projector, but again without success. We asked one of the administrative assistants in the reception area to contact tech support, but everyone had gone home. We began to feel a little panicked. Finally, after much commotion, we were able to borrow a portable projector that worked with our laptop and some extra long extension cords from the training department. The cords on the table disturbed the ambiance, but at least we were able to complete the rehearsal and deliver a respectable presentation the next day.

The experience in San Francisco was another important lesson for me regarding the presentation process. I was part of the executive team and spent countless hours working with others on content design, developing visual support, and rehearsing for a flawless presentation. However, I was reminded once again that all that work could be for naught if you do not pay attention to the logistical details, which must be an integral part of the delivery preparation. I was the one who insisted that we arrange for rehearsal in the actual boardroom, but I did not think to schedule someone from the technical staff to be present to help us navigate the computer issues and other aspects of the environment such as lighting. So, this chapter will be devoted to reminding you of things you need to think about and do as you prepare for the presentation itself—checking logistics, conducting rehearsals, and managing your nerves.

Checking Logistics

By logistics, I mean co-ordinating all the complex elements, including people, facilities, and materials that must come together to support your presentation.

We take too much for granted. We tend to assume that computers will not crash, the PowerPoint version I have on my laptop will work on your laptop, and we will never forget our power cord. Based on my own experience, here is a checklist to help you avoid a crisis when the stakes are high.

Tips from the Experts:

Do preventive and contingent planning—then you’ll always be able to present with confidence.

Claydyne Wilder

Point, Click, & Wow

![]() Backup your presentation.

Backup your presentation.

Create multiple backups. Port your presentation to a second laptop. Copy the file to a universal serial bus (USB) drive. Upload to the “cloud.” E-mail the final presentation to yourself. Be sure that video and other files used in the presentation are in the same folder. Avoid, as much as possible, requiring an Internet connection as part of your presentation—it is just too uncertain. Use screenshots instead. Rehearse using each of the backup presentation files to make sure all the files work. Finally, print a hard copy of your slides.

![]() Tune up your laptop.

Tune up your laptop.

Make sure virus and malware applications are up-to-date and your laptop battery will hold at least a 2-hour charge. Yes, sometimes, electrical outlets do not work. Buy an extra power cord and keep it in your computer case. Turn off the screensaver function, power-saving mode, automatic updates, and any other “pop-ups” that may disrupt your presentation.

![]() Carry a portable digital projector.

Carry a portable digital projector.

Even if your destination venue is providing a projector, as in my San Francisco experience, there may be technical issues. Today’s portable projectors are small, lightweight, and powerful. Either carry one with you or arrange to have access to one at your destination. Double-check to make sure you have all the cables and cords in the case along with a spare projector bulb.

![]() Replace the battery in your remote.

Replace the battery in your remote.

The remote is an essential tool, especially if you are using slide animation, allowing you to seamlessly and unobtrusively advance to the next image without losing connection with your audience. You do not want to be fumbling with the remote in the middle of your presentation if the battery dies. Keep a couple of batteries in your computer case, and put in a fresh battery before any important presentation.

![]() Become familiar with the room where you will present.

Become familiar with the room where you will present.

If you are not familiar with the scheduled room, if possible, rehearse in the room the day before. Arrange for a person from the technical staff to meet you to help with projection issues and lighting controls. In some cases, you may be able to make some minor adjustments to the room layout to better support your presentation style, such as the positioning of the podium. If the room does not have a whiteboard, ask for a flip chart to be available.

![]() Prepare an “emergency” presenter’s kit.

Prepare an “emergency” presenter’s kit.

Carry a small bag with a variety of resources, such as fresh whiteboard markers, water-based flip chart markers, duct tape, painter’s tape, a small screwdriver, an extension cord, a video graphics array (VGA) adaptor, and a three-prong plug. You will be surprised at how handy these resources can be in an emergency.

![]() Seek to be the first on the meeting agenda.

Seek to be the first on the meeting agenda.

Presenting first is a big advantage. You can arrive early, make sure all the equipment is up and ready, visit with the audience members as they arrive, and present while everyone is fresh and alert. Use your “social capital” and persuasive skills on this one to persuade whoever controls the meeting agenda to give you this favor.

I am sure you can add to the preparation checklist from your own experience. Of course, even with all the preplanning, “Murphy’s Law” can be in play. If the unexpected happens and you are not able to use your visuals, get out your markers, hand out the flip-books, use the whiteboard or flip chart, and engage with the audience. Remember, a major element of persuasion is trust and authenticity. The audience will be observing how you handle the crisis. Keeping a cool head and a positive attitude, perhaps with a dash of humor, will keep the audience on your side.

Now, with your logistics under control, let’s discuss the rehearsal process.

Conducting Rehearsals

You may have heard of the TED conferences, where interesting speakers from all walks of life deliver short presentations on “ideas worth spreading.” If you are not familiar with TED, I highly recommend you visit their website, click on the “Talks” section and the link “New to TED.”1 There you can sample some of the classic TED talks and observe how the speakers frame their stories, use visuals in a selective, creative manner to support their messages, and deliver in an authentic manner that engages the audience. According to Chris Anderson, the curator of TED, speakers begin their preparation six months (or more) in advance and within a month of the presentation are practicing the final version daily. Every speaker invests many hours in rehearsing the final product.2

Tips from the Experts:

It’s just a matter of rehearsing enough times that the flow of words becomes second nature. Then you can focus on delivering the talk with meaning and authenticity. Don’t worry—you’ll get there.

Chris Anderson

How to Give a Killer Presentation

Although few of us will become TED speakers or require six months of preparation time, I share the anecdote to reinforce the key idea in this section: practice, practice, practice. We tend to spend so much time in the content creation that we shortchange our rehearsal time. If you are not well prepared for the actual delivery, you will be less confident. If you are not confident during your delivery, you will not be persuasive. If the presentation is important to your business and your career, it deserves the necessary investment of your time.

The key, in my experience, is to follow a structured and progressive rehearsal process. Following are the steps that have worked best for me. You can adapt them to fit your own learning style, but the time investment is not optional. The goal is to “road test” the material and get to the point where you can speak comfortably without word-for-word memorization and without notes, cued by your slides and other prompts in your presentation flow. You want to be free to connect with and engage your audience.

1. Draft a script of your remarks

Some of the script writing occurs as you develop and frame your content. For example, in the opening, we identified a three-step process: gain attention, clarify your purpose, and provide an overview. Your oral remarks should require only a few well-crafted sentences under each of these steps. Read your remarks aloud to check for clarity and speak ability.

Carson Rodrequez’s opening for his tuition reimbursement presentation, which raised the issue of cost of turnover, is an example of how this works. If you recall from Chapter 5, Carson chose to use an image of an employee leaving through a revolving door. His script for his opening remarks to accompany the slide looked like this:

Have you ever thought about what the revolving door of employee turnover is costing our company? (Pause.) I think you will be surprised when you hear the answer. My purpose today ….

After your slides are close to final design, you can use the “notes pages function” in your presentation software to script your remarks under each slide. Remember to include transitions. Write for the ear, using shorter sentences and a conversational tone. When finished with your initial draft, print it in notes page view.

2. Conduct an oral “talk-through” using the script (alone or with your team).

This step is analogous to stage actors reading the script aloud on stage in the early stages of rehearsal. Project your slides and read the scripted remarks. Test for clarity and flow. Make edits as necessary. If you are presenting with others, the team needs to do this work together, providing feedback and helping each other. Keep repeating the process until you are comfortable with the content.

3. Conduct an oral “talk-through” using the script before an audience.

Now it is time to refine your script and slides in front of a small audience. The idea is to have some fresh eyes on the slides and some fresh ears on the narration. The trick here is to get the right people in the room, experienced presenters with some knowledge of the topic and capable of giving constructive feedback.3 In some cases, you may need to complete this step with your boss first, before you involve others. You will need to provide your audience with a background briefing drawn from your strategy analysis. At this stage, the focus continues to be on content, not delivery.

4. Reduce your script to bullet points and key words.

Make the necessary edits to your slides and boil your narration down to short bullet points and key words in notes page view. Print for further use.

5. Conduct stand-up rehearsals (alone or with your team).

Mimicking the presentation situation as much as possible, practice your talk with the bullet points as prompts. Each time, your narration will be a little different, which is good. Do not try to memorize word for word. With the slide as a cue, you want to communicate the main points without trying to remember the exact phrases. Practice the transitions also. Do everything you would do in front of the audience. This practice includes speaking at full volume and normal pace. Continue rehearsing until the flow of words becomes second nature. Then, you can concentrate on delivering the presentation with meaning and authenticity while focusing on the audience.

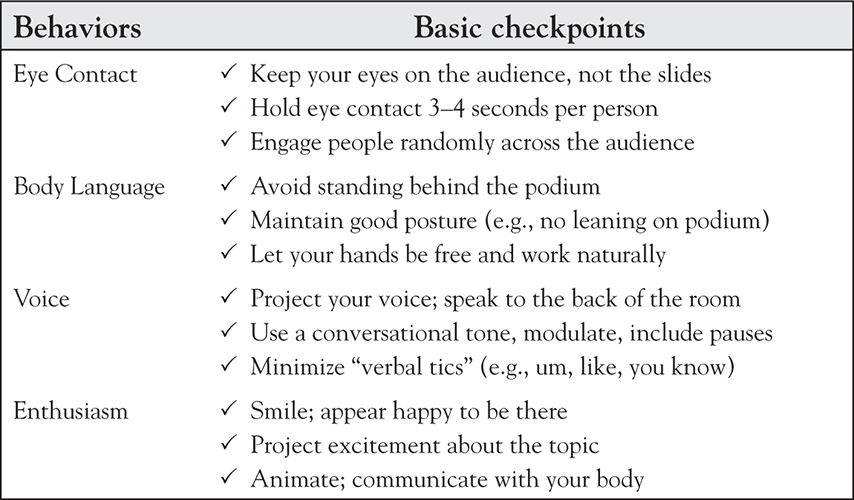

Although I don’t like to put too much emphasis on delivery mechanics (believing that passion, energy, and attention to your audience trump mechanics), the stand-up rehearsal is a good time to refine your delivery basics with regard to eye contact, body language, voice, and enthusiasm. Figure 6.1 provides checkpoints for behaviors you should consider. If any of these behaviors are an enduring problem for you, asking for help from a professional presentation coach may be appropriate. If you are well prepared and engaged with your audience, most of these behavioral issues will take care of themselves.

Figure 6.1. Checkpoints for delivery behaviors.

It is a good idea at this stage, if you can, to video record yourself. You will see opportunities for additional refinement.

6. Conduct a final stand-up rehearsal (with audience).

This step is comparable to a dress rehearsal, again with your carefully selected audience from the original script rehearsal. At the conclusion of the rehearsal, ask the audience to help you brainstorm questions you might receive from your target audience.

7. Create a one-page outline.

Finally, reduce your bullet points to a one-page key-word outline. This outline is your “security blanket” that you can place on the podium or table for quick reference if necessary. A full-page version of my flow diagram for a persuasive presentation, filled in with key words, also provides a great at-a-glance reference in the context of the presentation flow (Figure 6.2).4

Please avoid carrying note cards or a holding a piece of paper with notes in your hand. These behaviors are distracting and suggest you do not know your material. Remember, you have done the research, you believe in your topic, and you know what you want to say. Concentrate now on making a connection with your audience, not your notes or your slides.

I know these suggestions sound like overkill, but spending time in systematic and purposeful practice will make a huge difference in your confidence and the quality of your delivery. Relate the time you invest to the importance of the presentation to your company and your career.

Managing Nerves

I have included the discussion on managing nerves in this chapter because the best thing you can do if you are nervous about your presentation is to prepare in the manner we just discussed, making sure the logistics are covered and rehearsing until you are confident with your material.

Tips from the Experts:

Just before the talk, focus on the audience. Really look at them, their hair, eyes, chin, makeup—everything about them. If you do this with enough concentration, you will forget about being nervous, and you will have begun the all-important task of connecting with your audience.

Nick Morgan

Give Your Speech, Change the World

Feeling nervous is normal and necessary. You need the nervous energy to help you deliver your best effort. Part of the issue is psychological. Relabel your nervous feeling. Instead of saying, “I’m nervous,” say, “My adrenaline is up.” Adrenaline has a positive connotation, something necessary for peak performance. You can also use positive visualization. Run a little movie in your mind of you making a brilliant presentation and the audience responding with enthusiasm. Remember, the audience wants you to succeed. No one comes to a meeting hoping you will deliver a bad presentation.

To calm your nerves just before the presentation, here are some practical actions you can take.

The morning of the presentation:

• Use only the amount of caffeine you normally use.

• Avoid a heavy breakfast.

• Pump yourself up. Most professional speakers do some light exercise prior to speaking. I have found that even walking a few flights of stairs to get the heart rate up is very helpful.

• Do a quick walk-through of your opening and closing.

• Arrive early, recheck your equipment and materials, and then visit with the audience.

Just before the presentation:

• Consciously contract and then relax your muscles, starting with your feet and calves and working up to your shoulders, arms, and neck.

• Take several deep breaths from your diaphragm.

• Take a swallow of water to lubricate your vocal cords.

If speaking before others is truly a stressful issue for you, experience is the best anecdote. I strongly recommend participation in the Toastmasters organization.5 There are a number of clear benefits. Meetings are local and usually held during the lunch hour or in the evening. You will regularly deliver short presentations to a live audience in a low-pressure environment, receiving constructive feedback. You will see many speakers (fellow members) perform, some good, some bad, and you can learn a lot from both. Best of all, you will quickly accumulate hours of practice and experience to boost your confidence.

With the preparation in place, we are ready to talk about the actual delivery of the presentation in our final chapter.

Preparing for Delivery

• Manage the logistics in advance by co-ordinating all the elements that must come together to support your presentation: These include the following:

º Back up your presentation in multiple ways.

º Tune up your laptop.

º Arrange for a portable digital projector as backup.

º Replace batteries.

º Become familiar with the room where you will present.

º Ensure technical support people are available.

º Prepare an emergency presenter’s kit.

º Seek to be first on the agenda.

• Practice, practice, practice. Follow a structured rehearsal plan:

º Draft a complete script of your remarks; include transitions and key to your slides.

º Conduct an oral reading of the script in tandem with your slides, edit for clarity and flow, and tune for eyes and ears.

º Conduct a second oral reading with a selected audience new to the material, again focusing on content and slide design, not delivery.

º Reduce the script to short bullet points, key words, and symbols.

º Conduct repeated stand-up oral rehearsals until the flow of words becomes second nature; then concentrate on using eye contact, body language, and voice to connect with the audience.

º Conduct a final “dress” rehearsal with your selected audience.

º Construct a one-page outline of key points or create a flow diagram of key words to have on the podium for reference.

• Be proactive about managing your nerves:

º Accept nervousness as a good thing—a source of energy.

º Change the input to your mind by describing your feelings with positive words, for example, adrenalin; visualize success.

º Physically pump yourself up just before the presentation.

º Mingle with and concentrate on the audience, not yourself.