CHAPTER 4

MAKING IDEAS EVERYONE’S JOB

In 1880, the Scottish shipbuilder William Denny set up the world’s first industrial suggestion system. Since that time, the suggestion box has become the method of choice for seeking employee ideas. Despite modern touches—such as collecting ideas by e-mail, Web-based applications, or special hot lines—the underlying process is the same as it was in the nineteenth century. The strange thing is that everyone knows that suggestion boxes don’t work. Even cartoonists such as Scott Adams and Gary Larson poke fun at them.

Yet the suggestion box paradigm endures. In 2002, we received a call from a desperate executive at one of the largest insurance companies in the United States.

“My CEO just bought hundreds of suggestion boxes and ordered them put up throughout the company. He assigned me to make them work. What do I do? Every suggestion box system I have ever seen has been a total disaster.”94

Getting employee ideas involves a lot more than simply putting boxes on the wall. The suggestion box has fundamental limitations. It is a cumbersome and inefficient process that fails to engage employees and managers. It is premised on an archaic view of how organizations should be run, one in which employees check their brains at the door. (Some companies, as a French colleague pointed out to us, don’t even think their employees have anything to check at the door!) The box is there on the off chance that one of them might actually have a worthwhile thought.

Our advice to that distraught insurance company executive was this: Change the rules. What we mean by this, and how to do it, is the subject of this chapter. It is where the idea revolution begins.

“IT’S NOT YOUR JOB TO THINK”

At the beginning of the twentieth century, when Frederick Taylor introduced “science” into the practice of management, generally speaking he did the world a huge favor. In the first three decades after scientific management was introduced, it dramatically improved productivity almost wherever it was applied and thereby raised the standard of living around the globe. Unfortunately, Taylor saddled his new management method with a serious limitation, one that organizations still struggle with today.

This limitation was not something he overlooked; it was a concept he actively advocated as an essential component of his new approach to management:

95All of the planning which under the old system was done by the workman, as a result of his personal experience, must of necessity under the new system be done by the management in accordance with the laws of the science.… It is also clear that in most cases one type of man is needed to plan ahead and an entirely different type to execute the work.1

In other words, there are those whose job is to think and those whose job is to do. Well-managed companies take control away from the front lines, even the right to question procedures.

In our scheme, we do not ask for the initiative of our men. We do not want any initiative. All we want of them is to obey the orders we give them, do what we say, and do it quick.2

If Taylor were alive now and saying such things, he would be viewed as an embarrassment, a relic of a bygone era. One wonders how he would react if he were able to visit companies today that do not separate thinking from doing. Imagine him, for example, talking to employees at Wainwright Industries, a company in an industry that he knew well and that got sixty-five ideas per person in 2002. Taylor would recognize the lathes, the grinders, the milling and drilling machines, and the presses. But what would he be thinking as these employees showed him all the ideas they had implemented to save money and to improve productivity, quality, and safety? Wainwright has reached levels of efficiency that Taylor never even dreamed about, by doing exactly the opposite of what he advised.96

Unfortunately, in most organizations the division between thinking and doing is “hard-wired” into policies, structures, and operating practices, although it is rarely made explicit or even recognized for what it is. To overcome a century of ingrained bad habits, something radical is clearly needed. Instead of taking thinking out of the job expectations for employees, why not put it explicitly in? And why not manage our organizations for ideas, instead of simply for conformance and control. That is, make getting ideas part of every manager’s job—for supervisors, middle managers, and senior leaders. And design our policies, structures, and operating practices to smooth the way for ideas, rather than to obstruct them.

MAKING IDEAS PART OF EMPLOYEES’ WORK

In 1992, Martin Edelston, CEO of Boardroom Inc., invited management guru Peter Drucker for a day of consulting. Edelston had no specific goals in mind for the day; he simply thought that Drucker might give him some interesting insights. And indeed he did. At the end of the day, Drucker reported to Edelston that many employees had told him they were frustrated by the amount of time they were wasting in unproductive meetings. Drucker made a simple suggestion. Have everyone who comes to a meeting be prepared to give an idea for making his or her work more productive or enhancing the company as a whole in some way.3

Edelston liked the suggestion and decided to try it. Several years later, the policy was formalized and incorporated into the weekly departmental meetings. Today, employees who fail to give in an average of at least two ideas each week, however small, lose their quarterly bonuses. We asked Edelston how often people missed these bonuses because they couldn’t come up with enough ideas. “It hasn’t happened yet,” he told us.

Subsequent interviews with employees confirmed this. We were naturally a bit skeptical that for seven years every employee had produced two ideas per week without fail. With a little more digging the fuller story emerged. A lively black market had sprung up for ideas. A person who was short for a particular week would go to a coworker and borrow an idea, to be paid back at a later date. When we confronted Edelston with this discovery, we did not expect his reply. “Of course I know about this, but I think it’s great. We have succeeded in creating a culture that values ideas and gets people to share and communicate them. Wasn’t that the goal in the first place?”

Instead of taking thinking out of the job expectations for employees, why not put it explicitly in? And why not manage our organizations for ideas, instead of simply for conformance and control? That is, make getting ideas part of every manager’s job—for supervisors, middle managers, and senior leaders. And design policies, structures, and operating practices to smooth the way for ideas, rather than to obstruct them.

At first encounter, Boardroom’s approach seems a bold, even brassy experiment. It certainly makes ideas central to everyone’s work. But is the expectation of two ideas per week unreasonably high? We asked a number of veteran Boardroom employees this question, and not one thought the requirement unduly harsh. In fact, they appreciated the collaborative atmosphere it created and were challenged by it. In the meetings we attended, it was obvious that people were enjoying the process of sharing and discussing ideas, as well as solving problems that affected them. Ultimately, Drucker taught Edelston something much more important than how to run effective meetings. He showed him that he could raise his expectations of his workforce.98

Other organizations have made ideas part of the job in different ways. In 1991, Southwood “Woody” Morcott, CEO of Dana at the time, set a new corporate policy. From now on, every person in the company would be expected to come up with two ideas per month. According to Morcott:

We had to make it clear that innovation and

creativity—embodied in concrete ideas—would

not only be welcomed but expected.4

Dana, a highly decentralized company with more than sixty thousand employees in thirty-four countries, doing everything from professional services to manufacturing, left the details of how to implement the new policy to management at the operating unit level. Each Dana unit takes its own approach. Dana’s leasing operation, for example, with its salaried professional workforce, decided to begin each person’s annual performance review by going over the ideas that he or she had submitted that year. The Dana Spicer Axle Division in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, opted to offer monthly bonuses to people who give in their two ideas—with the size of the bonus depending on the aggregate effect of everyone’s ideas.

Milliken’s expectation of 110 ideas per person per year isn’t always an individual requirement but is sometimes written into the annual performance objectives of a work group. This requirement may sound stiff, but the ideas don’t have to be big. For example, in the guesthouse at company headquarters, one idea was to lower the wattage of a light bulb in a supply closet. Another was to put a special hook in each room for guests to hang their garment bags on, a simple convenience that most luxury hotels lack.99

Even if there is no organization-wide expectation for ideas, most managers and supervisors can create this expectation for their own employees. It can be as simple as saying, “I want you to bring an idea to each of our weekly department meetings.” Most people are grateful for the chance to contribute their suggestions on how to run the organization better. And as long as the proposed changes are within the manager’s domain, top management support is not an issue.

The real bottleneck to ideas is not usually front-line employees but the poor reception the ideas get from the organization. Changing this situation involves two things. First, getting employee ideas must become part of the work of every manager. Second, the organization itself must be aligned to support, rather than resist, ideas.

MAKING IDEAS PART OF THE WORK OF SUPERVISORS

In the mid-1960s, as the Vietnam War was intensifying, a lieutenant colonel put an idea into one of the Pentagon’s suggestion boxes.

His office produced a constant stream of reports for senior officers, all with the same format—an executive summary, a table of contents, and thick divider sheets with protruding alphabetically ordered tabs to identify the various sections. The divider sheets came in standard packets of twenty-six, one for each letter in the alphabet. What bothered the lieutenant colonel was that because most reports had only five or six sections, only the first five or six dividers in each packet were used. The rest were thrown away. Why not simply make the first section of each report be the letter after the one where the previous report left off, he suggested. That is, if one report used A through F, begin the next one with section G. The generals and senior officials for whom the reports were prepared would still have no trouble finding what they needed. The lieutenant colonel calculated that his idea would save the office several thousand dollars every year. He dropped it in the suggestion box and waited to see what would be done with it.

A few days later, he was brusquely summoned to the office of his commanding officer—a major general. He had no idea why he had been called in, but his boss was obviously furious. The younger officer stood stiffly at attention.

“Is this yours?” the general snapped, holding up a piece of paper that the lieutenant colonel recognized as his suggestion.

“Yes, sir.”

“Eat it,” the general said.

“Excuse me, sir?”

“Eat it. Now!” the general ordered. The lieutenant colonel stepped forward, took the paper from his superior, put it in his mouth, chewed it up, and swallowed it. He was abruptly dismissed and nothing more was ever said about it.

A supervisor has three important roles to play in managing ideas. The first is to create an environment that encourages them. Decades later, after that lieutenant colonel retired as one of the army’s top generals, he still remembered the way his former superior had humiliated him that day. It was the last time that the lieutenant colonel proposed any improvements while he worked for that officer.101

The second role of the supervisor is to help employees develop their knowledge and improve their problem-solving skills, in order to increase the quality and impact of their ideas. Strangely enough, the best learning opportunities often come from the worst ideas. Think about the lieutenant colonel’s idea. Was it actually a good one? Clearly, he had identified a problem—his office was throwing out huge numbers of unused dividers. But had he come up with a good solution? Of course not. Starting reports with section K or S would seem strange. People would wonder where the missing sections were. The general could see immediately that the idea would make his command look eccentric. And rightly or wrongly, if reports didn’t look professional, superiors would have less respect for their contents and would give them less weight in their decision making.

But when he rejected the suggestion in such an angry fashion, the general missed a chance to mentor his subordinate. A bad idea, given in good faith, reveals a lack of understanding on the part of the suggester. No matter how bad the idea was, the general should have seen it as a teaching opportunity. The lieutenant colonel was only trying to do his job. Had the general taken a minute or two to explain the proposal’s drawbacks, the lieutenant colonel might have learned something and have become a more effective (and loyal) subordinate for it. A great many organizations spend thousands of dollars—maybe millions in the case of the Defense Department—on consultants or internal studies to determine training needs. But here, for no cost, the general was handed a good training opportunity.

He also lost the chance to eliminate some significant waste. The lieutenant colonel had identified a problem, but perhaps not a workable solution to it. Once he was shown why it was unworkable, he might have been able to come up with a different way to address the problem. Or perhaps the general could have brainstormed a bit with his aide to come up with a workable solution. Maybe the office could purchase blank dividers and type the section letters in as needed. Or perhaps section dividers could be bought packaged individually by letter, so the office could buy more A’s than Z’s.

But worst of all, the general’s poor handling of the idea caused his subordinate to lose respect for him.

A supervisor has three important roles to play in managing ideas:

- To create an environment that encourages ideas;

- To help employees develop their knowledge and improve their problem solving skills, in order to increase the quality and impact of their ideas; and

- To champion ideas and look for possible larger implications in them.

The third role a supervisor plays is to champion ideas to superiors and the rest of the organization and to look for the larger implications that can underlie even the smallest idea. Once the lieutenant colonel’s idea was made workable, maybe it, or something similar, could have been used throughout the Defense Department. Or perhaps he could have thought of other supplies that were only being partly used. The two men might even have modified the idea and used it creatively as a visible reminder of the need to conserve resources in wartime. In short, supervisors can play an important part in unlocking the full potential in employee ideas.103

Incorporating these roles into supervisors’ jobs involves three things. The first is to make certain they understand why ideas are important. Many supervisors are surprised to learn of the potential for performance improvement that lies in employee ideas. Whenever we have found organizations with good idea systems tracking the sources of their performance improvement, most of it comes from employee ideas. For example, only a few years after a Johnson Controls facility in Kentucky started its idea system, the management team was already budgeting half the annual cost reductions it needed to come from employee ideas. At Dana, a company with a more mature system, one manager told us that his data showed 80 percent of newly identified cost savings coming from employee ideas. Supervisors who are able to get large numbers of employee ideas find their jobs becoming much less stressful, as many problems take care of themselves and their groups become increasingly able to do more with less.

The second thing needed to make ideas central to supervisors’ work is to give them training in how to manage ideas. Many of the necessary skills—such as listening, communicating, instructing, coaching, and helping people develop—are already part of an effective supervisor’s repertoire. But additional training will be needed in idea-specific areas, such as how to handle bad ideas, how to get an initially reluctant employee to give in an idea, how to help employees come up with more and better ideas, how to help employees build on their ideas and develop them further, and how to ferret out the larger implications of seemingly small ideas.104

The third ingredient needed to make ideas part of supervisors’ jobs is to hold them accountable for how well they manage ideas, just as they are held accountable for other important aspects of their performance. This means monitoring a few statistics, such as the number of ideas each supervisor is getting from his or her employees, the participation rate, the implementation rate, and the speed of implementation. These numbers can be used in different ways to hold supervisors accountable. They might be integrated into the supervisor’s normal performance reviews (as Dana does), publicized (relying on peer pressure and natural competitive instincts, as parts of Air France and Volkswagen do), made part of the criteria for promotion (as Sumitomo Electric and Toyota do), or used to recognize, celebrate, or even reward those supervisors who do well at encouraging ideas (as DUBAL does).

MAKING IDEAS PART OF THE WORK OF MIDDLE MANAGERS

From time to time, we come across idea systems in which middle managers are quietly resisting, or even outright sabotaging, perfectly good ideas. When we first encountered such behavior, we were quite puzzled by it. Why, we wondered, couldn’t middle managers see the value in these ideas? And how did they attain and keep their positions of responsibility unless they cared about being effective at their jobs and moving the company forward? For a while, we simply chalked each instance up to a bad egg—a person who was uncomfortable with change and was obstructing the process. But the more we were able to identify and talk with middle managers who behaved this way, the more we began to see the issue from their perspective. The problem was not them; it was the conflicted positions their organizations put them in. It sometimes made sense for them to stonewall, simply to get their jobs done.

Consider what happened at a utility company in the northeastern United States. In the late 1990s, the industry was deregulating, and the company needed to increase its efficiency quickly to survive. A new CEO was hired to bring about the necessary change. When he took over, to familiarize himself with the company, he spent several weeks visiting its front-line operations and talking with employees. He was astonished at the number of ideas they gave him to save money and work more productively. He ordered a system to be established as a way to capture their ideas. Although plenty of ideas came in, and managers knew the CEO wanted them acted on quickly, the effort soon ran into trouble. Even the best ideas took an inordinate amount of time and effort to implement. At one point, it was taking more than a year and a half to implement the average idea.

Middle managers play a vital role in the idea process. They make sure the necessary resources are available to evaluate, test, and implement the ideas and provide the necessary training. They must also oversee the process in their units and get personally involved with the more significant ideas.

The problem turned out to be with middle managers—behind the scenes they were obstructing implementation. From their point of view, it was the safest course of action, because of a flawed policy. As soon as an idea was implemented, the projected cost savings were immediately deducted from the affected manager’s budget. The CEO’s thinking was that he or she would no longer need the funds. But managers told us privately that this policy often made it dangerous for them to approve and implement ideas. No matter how carefully the projected cost savings were calculated, they were often overestimated, sometimes grossly so. There was a natural tendency for those advocating an idea to exaggerate its value. Suggesters, who received 10 percent of the value of their ideas, would naturally give optimistic assessments of their worth; the idea system manager was anxious to show results from his program; and top management was under pressure from the board of directors to demonstrate that it was reducing costs. Also, many ideas had unanticipated complications. They cost more to implement than projected, the inevitable adjustments and minor changes needed to make them work took more time than planned, or they created unanticipated problems. Middle managers, who had to live with the difference between the stated value of ideas and their actual results, found themselves surrounded by people whose self-interest was to inflate the estimated cost savings. And even if the projected cost savings were realistic, they often did not show up until the next budget cycle. Unwittingly, the tight budgeting policy of that utility company made it difficult for middle managers to support employee ideas. The only way out for them was to find some excuse to turn down ideas, scale them back, or slow their implementation.

Middle managers play a vital role in the idea process. They make sure the necessary resources are available to evaluate, test, and implement ideas and to provide the necessary training. They must also oversee the process in their units and get personally involved with the more significant ideas. Yet middle managers are frequently overlooked in the way organizations set up and run their idea systems, and they get squeezed between the well-intentioned policies of top management and the day-today realities they face.107

Once such misalignments are identified and people are made aware of them, they are often straightforward to remove. Take, for example, the problem at the New England utility. Had the CEO known about it, he could easily have set up a win-win situation. He wanted cost savings to flow more quickly to the bottom line. Middle managers are always glad to get more discretionary funds in their budgets. Why not let middle managers keep in their budgets all the savings realized from an idea for the first six months after its approval? Instead of resisting ideas, they would rush to get them in place as fast as possible. His middle managers would have become big fans of employee ideas.

Middle managers are in positions that are already tough enough. The last thing they need is an idea system that adds to their problems. They have to be given input into the way the idea system is run and perhaps even some autonomy to modify it so it works for their units. Once they are convinced of the value of employee ideas and given training in how to encourage, process, and implement ideas, they, too, should be held accountable for their idea-managing performance.

MAKING IDEAS PART OF THE WORK OF SENIOR LEADERS

Bruce Hertzke, CEO of Winnebago Industries, almost never travels on Fridays. Friday mornings are reserved for a special morning coffee gathering of all those who have had an idea implemented during the previous week, together with their managers. As the suggesters arrive, they are photographed with Hertzke. These photographs are published in the next issue of the company newsletter along with a brief description of each idea.

When the meeting starts, each suggester is asked to describe his or her idea and its expected results. Hertzke comments on each idea and thanks the suggester. After all the ideas have been heard, the rest of the meeting is dedicated to an open discussion of any issues that the employees or their managers want to talk about.

Leaders who are serious about promoting employee ideas have to design a role for themselves in the process. The role need not take much time, but it should keep them informed about the idea system’s performance and put them in regular and personal contact with suggesters and their ideas. The leader’s personal involvement has two purposes. First is the obvious need for overseeing the process and showing support for it from the top. If ideas are important to the company, the CEO has to ensure that everyone knows this and that ideas are being managed effectively. With just one hour per week, Hertzke makes it clear to both employees and managers that ideas are important to him and the company.

The second reason for the CEO’s involvement is to increase his or her effectiveness. Hertzke is rare among CEOs in that he started at Winnebago as a teenager working on the assembly line. There he saw how he and his fellow workers were not listened to, though they had all kinds of ideas for improving products and processes. As a result, he is keenly aware that the nature of his job distances him from the issues and concerns of those on the front lines. For Hertzke, the Friday idea meetings are a priceless chance to stay in touch. Many leaders find it very difficult to know what is really happening in their organizations. For example, at a roundtable of business leaders we once presented to, the CEO of one of the world’s largest drug companies commented that the most challenging part of his job was getting good information about what was really going on in the organization. “People tend to tell me what they think I want to hear,” he said. “Sometimes I feel very out of touch.”109

By hearing ideas, questions, and concerns directly from his employees every week, Hertzke stays in close touch with what is going on in his company and is regularly reminded that his people are a tremendous resource—they care about the company, are thoughtful and observant, and often see opportunities their managers do not. Many executives are quick to lay off employees to improve financial performance. But every company we are familiar with that operates a high-performing idea system is different. All have designed a significant role for senior managers into their systems. The experience these managers derive from interacting with employees teaches them to view these employees not as a cost to eliminate but as a source of help in times of financial difficulty.

Leaders who are serious about promoting employee ideas have to design a role for themselves into the process. This role should keep them informed about the idea system’s performance and put them in frequent personal contact with suggesters and their ideas. This continuously reminds them that their people are a tremendous resource—they care about the company, are thoughtful and observant, and often see opportunities their managers do not.

Take what happened at Toyota, for example, a company with a long-standing active idea system. During the 1973 oil crisis, Japan’s economy was hit severely, because the country imported almost all its oil. In less than a year, wholesale prices rose 31 percent, and consumer prices 25 percent. The automotive industry found itself in serious trouble. Gasoline prices went up by 60 percent, and the cost of some of its major raw materials rose by as much as 50 percent. Automakers were forced to raise the price of their vehicles substantially. At Toyota, sales plummeted by 37 percent.5 Many companies faced with such a crisis would have laid people off without hesitation. Instead, Toyota asked its employees for all the cost-cutting ideas they could think of that did not require major investment. The response was immediate. Prior to the crisis, employees had been averaging two or three ideas per person per year. In 1973 this jumped to twelve per person—a total of 247,000 ideas corporate-wide—and it is worth noting that the call for ideas didn’t go out until October, when the crisis began. Since 1950, Toyota has not laid a single employee off, worldwide.

Effective top management involvement in an idea system can take many different forms. At Milliken & Company, CEO Roger Milliken and President Tom Malone host quarterly idea “sharing rallies,” at which the employees with the best ideas in that quarter present them to top management. Don Wainwright holds weekly recognition breakfasts for employees who have given in ideas. Every March, DUBAL, the aluminum company in Dubai, holds an annual celebration of its idea system. The one we attended in 2001 included more than two thousand company employees as well as guests from government and private sector companies. Over a hundred employees received awards for different achievements, such as “Best Supervisor” (in each of eighteen areas); “Best Suggester” (in each of eighteen areas); “Best Suggestion” (in each of eighteen areas); and first, second, and third places in a number of categories of suggestion, including energy conservation, quality, safety, and environmental.111

Although CEO John Boardman personally presents each award, his main involvement occurs during the previous three months, when he leads the CEO’s adjudication team, which visits all the finalists for “Best Suggestion” in their workplaces. Boardman and his team of the company’s general managers listen to each suggester explain his or her idea in detail and they see it in operation.

In the course of our research and work, we have noticed a marked pattern with CEOs. When asked to share some of their favorite employee ideas, some CEOs have plenty of specific examples, but many do not. The response to this request has proven a good indicator of whether a CEO is personally involved in the idea system. If the CEO hedges, perhaps by talking vaguely about how hard it is to single out any particular idea, and quickly changes the subject, we invariably find that top-level involvement is minimal—and so are the benefits from the idea system.

MAKING IDEAS PART OF THE ORGANIZATION’S WORK

So far, we have been discussing how to make ideas a regular part of everyone’s work. But doing this will have little impact unless the way the organization governs how work is done is aligned to promote ideas, too. Consider the following example.

In 2003, we helped a unit of a large medical products company to launch a new idea system. The vice president in charge of the unit had formed a team to design the process. Members of the team had worked hard, done their jobs well, and even proposed ways to make ideas part of everyone’s work. Unfortunately, the organization itself was not ready for employee ideas.

One problem was that front-line supervisors were spread very thin. In some cases, a single supervisor had fifty direct reports. Moreover, many supervisors had to spend literally half of their time in meetings and were constantly blindsided by urgent tasks from above. A number of supervisors estimated that they were able to spend at most 20 percent of their time actually supervising. At the same time, front-line employees complained that it was extremely difficult for them to get any attention from their supervisors. No matter what the team designing the process added to supervisors’ job descriptions, how could supervisors really be expected to fit anything more into their hectic schedules?

Making ideas a regular part of everyone’s work will have little impact unless the way the organization governs how work is done is aligned to promote ideas, too. The best idea systems are so completely integrated into the way the organization operates that they are indistinguishable from other systems and processes.

Front-line employees had a similar problem. The accounting system was set up to allocate their time to the production of specific products. There was no way to allocate time for them to meet and talk about ideas, let alone help implement them.

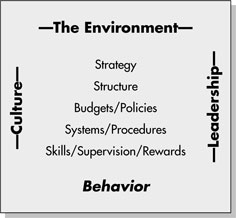

Figure 4.1 The alignment ladder

Many additional misalignments were identified. Supervisors and managers faced conflicting performance metrics; budgets were so tightly controlled that it would be difficult to get the resources to implement many ideas; everyone complained of poor vertical communication and communication between shifts. Even ideas with no impact on product integrity had to go through engineering review. It was clear to us that in order to make the new idea system a success, managers were going to have to realign the organization to handle employee ideas.114

A handy conceptual tool for thinking about alignment is the ladder shown in figure 4.1. Its logic is as follows. An organization faces a certain external environment. The strategy it follows must successfully draw needed resources from that environment. The organization’s structure should be designed to support the strategy, as should the policies it follows and the way it budgets its resources. The systems and procedures it deploys, in turn, should be consistent with its strategy, structure, budgets, and policies. Smoothly meshing with all of this are the way people are rewarded, the skills they are given through training, and the way they are supervised. The ultimate goal is to assure that throughout the organization, individual behavior—in this case submitting and managing ideas—is in line with the organization’s strategic direction. The role played by the organization’s culture and its leadership is to keep all these elements aligned. Resistance to ideas will arise when any of these elements are out of step with managing employee ideas, and mixed messages will be sent to people who have been told that generating and working with ideas are critical parts of their jobs.

Misalignments manifest themselves in many ways. Earlier, in the section about middle managers, we discussed how an electric utility put its managers in a difficult position when company policies inadvertently conflicted with implementing ideas. This was a fairly obvious example of misalignment because it resulted in already-approved ideas being blocked. In most cases, poor alignment is more subtle. It merely causes some aspect of the idea system to underperform—people may not step forward with as many ideas, processing might take longer, and some areas of the organization could resist ideas from other areas. However misalignments happen, they make it more difficult for people truly to embrace working with ideas as a normal part of their job.

The best idea systems are so completely integrated into the way the organization operates that they are indistinguishable from other systems and processes. Working with ideas is simply part of the way everything is done.

115KEY POINTS

- Traditional management practice is to take thinking out of the jobs of front-line employees. Best-practice companies put it explicitly in. Employees are expected to come up with ideas as part of their normal work.

- A supervisor has three important roles to play when it comes to managing ideas: (1) to create a supportive environment; (2) to coach, mentor, and develop subordinates’ skills in coming up with ideas (the best learning opportunities often come from the worst ideas); and (3) to help flesh out and properly develop employee ideas, champion them, and look for their larger implications.

- The middle manager’s job is to promote ideas in his or her area, assure resources are available for training and implementation, and become personally involved with more substantial ideas that require his or her attention. To assure that middle managers are not put in conflicted positions, top management has to eliminate any misalignments in policies or practices that send inconsistent messages.

- Leaders should be personally involved in the idea system for two reasons: to champion it and oversee its performance and to increase their personal effectiveness. Regular contact with front-line employees reminds them that employees are a tremendous resource—thoughtful and observant people who often see things their managers don’t.116

- The way the organization governs how work is done should be aligned to promote ideas. The best idea systems are extremely well integrated into the way the organization operates.

GUERRILLA TACTICS

Five actions you can take today (without the boss’s permission)

- Make ideas a priority for everyone. Make consideration and discussion of ideas the first item in your regular department meetings. Incorporate ideas into the annual performance review process. Assess how well each person does at coming up with or encouraging ideas. Talk about how he or she might improve, and identify training and development opportunities.

- Publicize results. Track the number of ideas people are submitting. For supervisors and managers, track the number of ideas they are getting. Post the results.

- Address bottlenecks. If it takes too long to process ideas, find out why. Are people sitting on ideas for good reasons? Is the problem caused by a misalignment? Ask people about unintended consequences of policies or practices that are getting in the way of dealing with ideas.

- Exploit learning opportunities. When someone suggests a bad idea, treat it as a learning opportunity. Why did that person think it made sense? What information, knowledge, or training do you need to provide to that person?

(continued)

118 - Recruit your boss. Life will be a lot easier if your boss is supportive. Start a campaign to regularly bring great ideas to his or her attention. It may require subtlety, but when constantly confronted with ideas that your people have offered and that have helped achieve goals and have improved performance, he or she should eventually come around.