Chapter 11

Chapter 11

Leadership Development Strategy

Tacy M. Byham and William C. Byham

In This Chapter

- Why only a small fraction of leaders take action on their assessment feedback.

- Five practices that define an effective leadership development strategy.

- The roles of the individual leader and his or her supervisor in planning and successfully completing development activities.

- The development activities most appropriate for leaders at different organizational levels.

Successful leadership development is driven by actionable information and individual accountability, but there is often a disconnect between these two requirements. In many organizations, individual leaders are assessed and receive feedback on the basis of their strengths and development areas. Yet surprisingly few leaders act on the feedback they receive by actually pursuing their further development.

This chapter examines the reasons why leaders fail to act on the basis of assessment feedback. In addition, five practices are identified that constitute an effective leadership development strategy whereby individual leaders receive the support they need and are held accountable for their own development.

A talent crisis is looming around the world. Global companies are aware that they need to grow leadership capability—and they need to do it soon—or face being hamstrung in executing their business strategy. Yet awareness of the problem is not translating into progress toward resolving it. Consider these facts:

- 55 percent of CEOs and senior leaders (globally) expect business performance to suffer in the near future due to a lack of leadership capability (DDI and Economist Intelligence Unit 2008).

- 46 percent of leaders around the world did not get the support they needed to be successful in their most recent promotion (transition) (DDI 2008a).

- Leaders report that their most difficult challenge is the need to understand the hurdles at the next level and how to prepare for them (DDI 2008b).

Clearly, organizations need to develop global leadership capability, and they are doing too little. But what should they be doing to be successful? We believe that their actions should be marked by two indispensable requirements: better information and greater accountability. From our work with leading organizations around the world, we have seen firsthand how the use of accurate, predictive information helps drive decision making about who has the talent to succeed in key leadership positions, how to develop leaders faster, and where to deploy these leaders when they are ready to step up. Better information also helps organizations reduce risk and ensure success throughout their entire global leadership pipelines.

But high-quality information is of little value if the use of this information for development is not accompanied by accountability. Strategically, we view the accountability for development on two levels: (1) the organization’s leadership development strategy and (2) the individual leader’s personal commitment to leadership development activities. The successful development of leaders demands processes on both levels that are well planned and properly executed.

Most high-performing organizations today purport to have a sound process for organizational leadership development in place. However, with respect to individual leadership development, we believe that while millions of leaders at all organizational levels may make plans to improve their leadership and management skills, relatively few (probably less than 10 percent) actually act to change their behavior, develop skills, overcome personality derailers, or acquire new knowledge and experience to optimize their current performance and prepare for higher-level positions. We believe this poor record is attributable to

- inaccurate determination of development needs—individuals either don’t know or don’t fully accept their leadership strengths and weaknesses relative to their current or future jobs

- inappropriate prioritization of development needs—leaders don’t consider the organizational importance of their development targets

- poor selection of development activities—the most effective development tools are not applied

- poorly conceived and implemented development plans—individuals don’t have opportunities to practice their newly developed skills in a timely manner

- lack of emphasis on measuring progress toward, and the achievement of, development goals.

In this chapter, we propose an individual leadership development strategy, defined by five strategic practices, that is, in some regards, radically different from the common strategy used by most organizations. In proposing this strategy, we assume that two common human resources (HR) practices or tools are in place.

The first practice or tool is success profiles—well-defined job profiles that describe what is needed to be a successful leader at each organizational level. Organizational leadership development strategists should begin by identifying the three to five business drivers that are most relevant to the organization’s strategy and future success. Creating alignment and accountability and forging strategic alliances are examples of business drivers that may resonate with senior leaders. The choice of business drivers will determine the success profiles upon which subsequent assessment measures and development activities will be based. The success profiles, in turn, include job challenges (preparatory experiences) and organization knowledge needed, along with behaviorally defined competencies and important personal attributes (personality factors) that can enable leaders to succeed or cause them to derail.

A success profile represents a complete picture of what’s required for an individual to succeed in the target job or role. Unfortunately, most organizations don’t take such a holistic view of development targets. In their leadership development programs, they focus only on assessing and developing competencies and a few personal attributes, although they may informally consider the experience and organizational knowledge required for promotions or development.

The second practice or tool is performance management—a system that includes evaluations of the competencies important at each organizational level and that accurately measures job performance. As a requirement for the effective use of a performance management system, managers should have been trained to communicate strengths and weaknesses, give explicit examples illustrating both positive and negative behavior, and do so in a timely manner throughout the year.

Strategic Practice 1: Help Individuals Understand and Buy into the Strengths and Weaknesses Revealed in 360-Degree or Assessment Center Feedback

An organization can have sound organizational development approaches and programs, but if individual leaders don’t recognize and accept their development needs, then these approaches and programs are wasted. This is why the first thing most organizations do to effectively demonstrate strengths and weaknesses in relation to the full success profile is supplement feedback from the individual leader’s immediate manager with feedback from other sources. Assessment measures most used to illuminate elements of the success profile are multi-rater (360-degree) surveys and assessment centers (simulation-based assessments), which often include personality tests.

Multi-Rater (360-Degree) Surveys

Many organizations rely heavily on 360-degree feedback to provide insights into positive and negative areas of current job performance and to convince people of their need to develop. Feedback from a 360-degree survey is a wonderful way for an individual leader to learn how others see him or her on the job, as the individual’s manager, peers, and subordinates complete a rating of competencies. As part of this process, the individual also provides a self-rating.

However, less than 10 percent of the people receiving 360-degree feedback actively change their behavior in a positive way and sustain that change for several years (Byham and Weaver 2005). Why? We believe that some are confused by the definitions of the competencies being rated, and they may wonder if the competencies are truly related to important measures of organizational success. Others see their feedback as a report card rather than as a road map for development. Most important, many have difficulty accepting the need for taking action on their 360-degree feedback. Those who hold this view frequently make comments such as

- “All my ratings are in the favorable range. I am just dealing with different degrees of goodness.”

- “All my ratings are above average or above the norms presented with the feedback.”

- “My average rating is favorable, even if some competencies are low.”

- “I’ve made it to where I am without being proficient in all these competencies, so I don’t need to change now.”

Or they dismiss the results due to what they perceive as shortcomings in the 360-degree process:

- “I had the wrong raters.”

- “The raters don’t understand why I do things.”

- “I’ve changed since they rated me.” n “These ratings were influenced by poor morale or other factors outside of my control.”

Whether or not 360-degree feedback is accepted depends upon how the output of the survey is communicated. Even the most comprehensive assessment is meaningless unless the person being assessed acknowledges the accuracy and value of the data and willingly recognizes the diagnosed development needs. To work toward making this happen, after the 360-degree evaluation is complete, the subjects (that is, the individual leaders who have been rated) should meet with a skilled person who can explain why the competencies were chosen and why the results are important. (What shouldn’t happen is that the subject receives the results, with little or no explanation. Yet even though this can have an adverse impact on the individual’s acceptance of the feedback, it’s common practice in most organizations today.)

In a well-conducted feedback discussion, the individual leaders are asked to draw connections between the insights from peers and their supervisor and additional feedback they have received on or off the job. These discussions often elicit comments such as “I’ve heard this before from others” or “My spouse tells me that all the time.” These comments amount to the individual’s confirmation and acceptance of the 360-degree feedback.

When 360-degree feedback is communicated properly and supported with meaningful discussion, the result is a significant increase in the process’s return on investment.

Assessment Center Experience and Personality Inventories

Although a 360-dgree assessment allows leaders to hold a mirror of self-insight up to their performance in their current jobs or roles, an assessment center experience foreshadows capabilities for future jobs. A typical assessment center for leaders involves component parts such as role-play interactions, email-based judgment items, the development of a strategic plan, an oral presentation, and a personality test. The experience is job-relevant, realistic, and covers a broad range of leadership challenges so that leaders can be observed using their entire repertoire of skills.

Today’s assessment centers employ state-of-the-art technology and world-class facilities, ensuring that participants encounter an engaging process that is challenging and developmental from the outset. This degree of process realism contributes to assessment centers producing significantly richer information on candidate strengths and development needs than do 360-degree assessments. Another benefit of this realism is that subjects are more likely to accept feedback from an assessment center than from other assessment methods.

A personality assessment is typically included in a full assessment center experience. Personality characteristics play an important role in enabling those concerned to understand why leaders succeed and why they sometimes fail, despite having strong skills. Traditionally, personality assessments have been seen as a window into the bright side of personality, the dark side of personality, and the values and other factors that motivate individuals. Together, these assessments provide a rich picture of the personal attributes that underlie leadership performance. For example, they can reveal early indicators of whether confidence may veer toward arrogance, whether passion may slide into volatility, or whether highly sociable individuals may become self-promoting. These personality derailers can have significant consequences.

Assessment center feedback must be delivered to the individual leader by a highly skilled internal or external consultant trained in the holistic integration of assessment data. This is because assessment centers are usually designed to evaluate individuals relative to higher-level, future-focused jobs, and also because of the large quantity of information gathered during assessment. The vast majority of the leaders who participate in assessment centers agree that the assessment experience provides personal insights into knowledge, skills, and abilities (95 percent), and serves as a catalyst for change (81 percent; DDI 2003).

A Combination of Data Points Produces the Most Accurate Diagnosis

Generally, the more sources of job-related data (360-degree feedback, assessment center feedback, and so on), the better the accuracy and the higher the likelihood that the individual leader will accept the feedback. Consistent findings across various methodologies lead to increased believability and acceptance. Table 11-1 shows the quantity and quality of information that can be gleaned from common options.

Once the assessment data is effectively communicated and the individual has acknowledged that the feedback is both valid and actionable, he or she should be encouraged to focus development efforts on one strength area to build on and one weakness to shed. After those are completed, two more can be selected.

Table 11-1. Quantity and Quality of Assessment Information Provided by Assessment Methodologies

| Assessment Tool | Competencies | Experiences | Knowledge | Personal Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulations | XXX | X | ||

| Multi-rater (360°) surveys | XX | X | ||

| Personality inventories | X | X | ||

| Behavior-based interviews | XX | XX | XX |

Note: The Xs denote the quantity and quality of information; the more Xs, the greater the quantity and quality.

Strategic Practice 2: Ensure that Development Goals Have an Impact on Current Job Performance

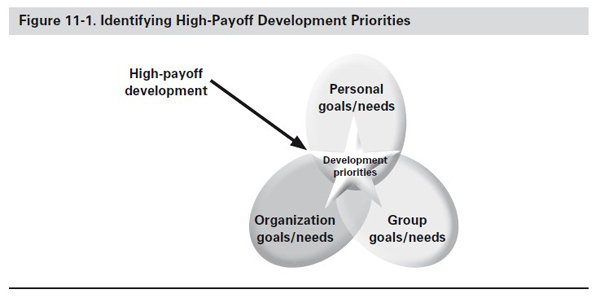

Research and experience show that strong manager support is the key driver of sustainable leadership development at all levels. This support is critical because most leaders, especially those with high potential, have more on their plates than they can easily handle. As a result, time pressures often make development difficult. If the support of their managers is lacking, the majority of leaders will put off their development activities to the following year—a delay that greatly lessens the likelihood that the development will be completed at all. Considering organizational and group needs when prioritizing development needs is the key to an individual obtaining the support of his or her manager.

When left to their own devices, individual leaders can choose inappropriate development priorities. For example, they may select development targets that are

- too easily achievable, convenient to correct (they know there is a training program available), or socially acceptable (for example, looking to be placed on a project team that includes several peers)

- of particular interest to them but that are not the development targets that would have the greatest impact on their own, their team’s, or the organization’s performance

- undoable because of competing job demands (they likely will later claim that “work got in the way of my development”) or because resources or cooperation from other parts of the organization probably will not be forthcoming.

Managers can remedy these challenges by helping leaders properly view their strengths and weaknesses with respect to the needs of their unit or of the organization (figure 11-1). Such a view leads to more accurate insights into the relative payoffs possible from achieving alternative development goals. Having goals directly related to areas of positive unit or organizational impact will increase the likelihood that more people will have a vested interest in the individual’s success. For example, a manager will be less likely to pull a person from a training program or cut off a development opportunity. Hence, rather than work getting in the way of development, good development priorities ensure that work is the way to development.

An example would be an individual who has been put in charge of an important company-wide task force, the success of which is an objective on the individual’s manager’s performance plan (group goal/need). For instance, originally, the individual had chosen to learn French (personal goal/need) as a development priority because the company is French owned. He rightfully thought that knowing how to speak French would be important for his advancement in the company (organizational goal/need). But his manager, knowing the importance of the task force and having a vested interest in it succeeding, instead suggested that the individual focus on meeting leadership, a competency identified as a deficiency when the individual went through an assessment center. Because improving meeting leadership skills is critical to the success of the task force, and this success means that the manager will meet his own performance goals, the manager will clear the deck for the individual to get trained in meeting leadership and will point out individuals who are particularly good in this area and assure that the individual will have the time to observe them.

The time available for development will always be limited, so the individual leader’s efforts must support those goals that represent the highest payoff for him or her, the group, and the larger organization, and that can ideally be integrated into normal job responsibilities.

Now let’s shift the level of our conversation up from the individual’s commitment to development to the organization’s leadership development strategy. From up here, we see that too often individuals who receive assessment center or 360-degree feedback use the person delivering the feedback (usually an HR professional or someone from outside the organization) as a sounding board for determining development priorities. Though the person communicating the feedback may be extremely competent and willing to help, we believe the best sounding board is the individual leader’s manager and that the individual and his or her manager should make development priority decisions together.

The manager’s involvement in setting development priorities is critical because the manager is able to

- assist the individual in targeting the competencies, knowledge, experience, and personal attributes that will have the greatest immediate and long-term impact on the individual’s career, and the success of his or her group and the organization

- provide growth opportunities (for example, job assignments, membership on a team)

- arrange access to organizational experts, training, or other support

- help the individual execute on his or her development plan n deliver ongoing feedback on the individual’s development and provide coaching as needed

- provide ideas on possible measurements for tracking progress.

Having an HR or training specialist discuss priorities and development plans is certainly better than the individual leader not discussing them with anybody, but it is not an optimal solution.

Strategic Practice 3: Help Leaders Select the Most Efficient and Highest-Impact Development Solutions

Leaders can develop competencies in many different ways, with a combination of methods often proving the most effective approach. Surveys of successful leaders from all organizational levels have shown the value in a combination of development options— a 70/20/10 development mix—for achieving development goals (see figure 11-2; the specific competency or other area of the success profile being developed will dictate a method’s appropriateness):

- Seventy percent of development should entail learning from experience—new job assignments, in-place developmental assignments, off-the-job experiences, cross-functional assignments, stretch assignments, and job rotations. Leaders learn most from experience when they have a chance to understand a skill or knowledge area in depth, when it is critical to demonstrate a skill, and when they can practice the skill in a real-world setting.

- Twenty percent of development should include opportunities to learn from others—feedback from mentors, leaders, peers; 360-degree feedback; ongoing, real-time observation and coaching; shared experiences; job shadowing; and networking. Leaders get the most from learning from others when the skill is new or unique and risk of failure is moderate to high. This approach is also beneficial when a person has low confidence and needs encouragement from a more skilled person.

- Ten percent of development should be devoted to attending training sessions— online, web-based, instructor-led, self-study, reading, seminar, or industry-related conferences. Leaders get the most from training sessions when creating or enhancing basic skills or knowledge, or when they are trying to gain cognitive knowledge or a framework from which learning and skill building will occur.

It’s also important to consider two other factors when planning high-impact development activities. First, consider the individual leader’s preferred learning styles (learning by experiencing, reflecting, thinking, or doing) and his or her motivation to make positive change in a competency or some other target. Second, consider the individual’s level within the organization (table 11-2). Formal training is most important for first- to middle-level leaders when they are trying to gain cognitive knowledge or a framework from which learning and skill building will occur on the job. Coaching and key stretch assignments or experiences will need to play a predominant role at senior levels in the organization.

After development goals are prioritized, the logical next step for a leader is to seek help in determining how development will be accomplished. As in prioritizing development goals, usually the best guidance comes from the individual’s manager, because the manager is familiar with the individual’s job and therefore understands the opportunities to acquire and practice skills. In addition, when the manager is involved, he or she will have even more ownership of the individual’s development plan. Thus, for instance, when the individual needs to miss some work to accomplish a development objective, the manager will likely understand the situation (maybe the manager even suggested the learning experience) and agree that the development action must take priority.

Table 11-2. Decreasing Rank Orders of Learning Activities by Leader Level

| Overall | First/ Middle | Higher/ Senior | Source of Learning |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | Supervisors at my company |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | Trial and error |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | Special work assignments |

| 4 | 6 | 2 | Co-workers (not including your supervisor) at my company |

| 5 | 3 | 5 | Observing others |

| 6 | 7 | 7 | Formal educational experiences |

| 7 | 8 | 6 | Reading |

| 8 | 5 | 9 | Formal on-the-job training |

| 9 | 9 | 8 | Formal training experiences |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | Professional colleagues at other organizations |

| 11 | 11 | 11 | Family and friends |

| 12 | 12 | 12 | Internet or online resources |

Note: A rating of 1 = most-valuable experience.

Source: DDI (2007).

If an educational effort is involved, such as selecting an appropriate training program, then representatives from HR should also be involved in the discussions. This is because HR, as the entity that designs and implements most leadership development programs, will have specific insights and information about the knowledge or skills that will be imparted by a training program.

In many cases, the prioritization of development objectives and the planning for accomplishing the objectives are handled in the same meeting between the individual leader and his or her manager. But sometimes a second meeting is required. Development planning forms are an invaluable tool for facilitating these meetings and for helping to decide how development will be accomplished.

Strategic Practice 4: Have Individuals Complete a Development Planning Form After Discussion with Their Managers

A story that we’ve heard told at professional development conferences goes something like this: In the mid-1950s, researchers surveyed graduating students at Yale University and found that only 3 percent had written down clearly defined goals. Twenty years later, the members of that particular class were polled again, and researchers found that the 3 percent who’d had the written goals had accumulated wealth worth more than the other 97 percent combined. As it so happens, this story is untrue (Tabak 2007), but it has become the stuff of urban legend.

Within the realm of what is true, we have actual data suggesting that leaders who craft wellthought-out written development plans are more likely to accomplish their development goals. In 2002 and 2003, Tacy Byham interviewed 79 midlevel leaders from a manufacturing organization a year after they had received development feedback based on several assessment instruments, including an assessment center, personality tests, and a 360-degree survey. Though, anecdotally, most of these leaders reported that the assessment and feedback had been the “most rewarding development experience of their careers,” few had made ongoing efforts to correct deficiencies and build on strengths.

Tacy was curious as to whether these individuals completed the recommended individual development plan (IDP) for each goal that was provided as part of their assessment feedback and if that plan made any difference in their development. The results were not encouraging: Only 11 percent of the leaders actually created a written development plan, although the organization expected that they would do so. Most of the others (42 percent) favored a “mental plan” with no actions put in writing. The rest (47 percent) did not follow up on their development at all. Those who completed an IDP were significantly more likely to take development actions and view their development efforts as a success (Byham 2005). This data is amazingly close to a survey by Bersin & Associates (2009), which indicated that 52 percent of managers have development plans but only 8 percent have high-quality plans.

What constitutes a high-quality development plan? Effective plans deal with three issues:

- How the skills, knowledge, and competencies will be acquired (if necessary). What training or coaching will be needed before the individuals can practice or apply the target skills, competencies, and the like? Also, it is important to anticipate and articulate barriers or challenges to success that may arise (for example, not being able to attend a training program, getting pulled out of training due to job demands, not having the time or travel funds to pursue a task force opportunity). Anticipating barriers or challenges prepares the individual leader to discuss with his or her manager what support or resources will be needed to avoid them.

- How the skills or knowledge will be practiced (or applied). Leaders should enlist the help of their managers in coming up with creative application opportunities. For example, if a leader needs exposure to the organization’s international operations but is unable to take a long-term assignment abroad, the individual’s manager may provide support by organizing a short-term role in a global initiative, such as the international rollout of a new product.

- How learning will be measured. Progress and outcome measures capture the degree to which leaders are developing new skills. We discuss these below.

An IDP should be completed for each development goal. The best practice is for the manager and the individual to talk through each section of the form during the development planning meeting. The role of the HR person is to facilitate the process with actions such as suggesting how two needs can be grouped under one goal or recommending measurement options. HR’s role is not to create or dictate the plan. Instead, the IDP should be a mutually agreed-to plan between the individual and the manager.

Strategic Step 5: Insist That Leaders Set Measurable Development Goals and Review Progress

The last part of an IDP is an agreement on how the plan’s progress will be monitored and how it will be determined if the development objectives have been met. This agreement is especially critical if the plan will take months (or even years) to complete. Tentative decisions on how progress will be tracked should be made when the development plan is discussed and agreed to. Often, identifying measurable objectives will serve to firm up the plan and improve its focus on key objectives.

Measurement should occur on both the individual and organizational levels. For the individual, three forms of measurement are important:

- Measurement associated with competency or knowledge acquisition (progress measures). Progress measures capture the degree to which development targets are achieved. They provide quick feedback that aids the individual leader in honing skills or changing behavior. They can cover a wide range of measurement options that fall across two categories: measures of perceptions (for example, feedback from the people who can observe behavior or decisions made by the leader) and short-term operating data (for example, weekly or monthly statistics on business performance that are tied to the individual leader’s performance).

- Measurements associated with the application of what is developed (outcome measures). The best outcome measure of the use of a competency or knowledge is the successful completion of a relevant project or assignment. For instance, to develop skills in project management, one might have been given a task demanding the coordination of the work of several groups. Success in carrying out this task would offer clear evidence of the individual’s successful application of project management skills.

- Measurements associated with continued application of what is developed. The function of these measurements, which capture the impact on the organization of the individual’s ongoing use of a competency or knowledge, is to help maintain focus and motivation to continue applying the new skills or knowledge. These measures will reveal if the individual is slipping back to old, less-effective ways.

For example, some areas to measure that would indicate continued application could include

- the number of leaders promoted internally (measured against status quo)

- the retention of key leaders and/or those with high potential

- time to mastery for defined leadership capabilities at each level.

Key metrics should be defined up front to truly drive the leader and the manager to be accountable for development. Defining key metrics in advance provides assurance that individual leaders will maintain their focus on their development and that their managers will remain committed to helping them.

As illustrated in figure 11-3, research shows that a measurement focus significantly affects the quality of a leadership development strategy.

Conclusion

Today’s global organizations need more leadership capabilities, and the key to satisfying this need is doing a better job of developing leaders. Toward this end, both organizations and individual leaders must quit fooling themselves that quick fixes or easy cures will produce results.

Developing leadership and management skills takes time and effort. Too often, people choose training programs that promise a change in attitude or increased personal awareness. But these programs don’t build new leadership skills and don’t provide opportunities to practice or apply new skills or knowledge. It’s like watching a yoga video but never practicing the movements—there is little chance of successfully acquiring the needed development.

To improve, leaders need an accurate diagnosis of their development needs, the opportunity to acquire needed skills or knowledge through training or other means, and on-the-job experiences that offer opportunities to not only apply new skills and knowledge to ensure success, but to also continue to build on them. They need to work with their managers to attain buy-in and ensure they get the support they need to make development happen.

Organizations also need to realize that development is not the job of the HR or training department. Those responsible for these functions can only act as catalysts and coaches. The responsibility for development must rest with the learner and his or her manager to build the knowledge, competencies, and personal attributes needed for success—for the leader, the manager, and the organization.

Further Reading

Ann Barrett and John Beeson, Developing Business Leaders for 2010. New York: Conference Board, 2002.

William Byham, What Now? The Little Guide to Using Your Assessment Center Results to Make Big Things Happen. Pittsburgh: DDI Press, 2005.

William Byham, Audrey Smith, and Matthew Paese, Grow Your Own Leaders. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times / Prentice Hall, 2002.

Richard Lepsinger and Antoinette D. Lucia, The Art and Science of 360-Degree Feedback. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

References

Bersin & Associates. 2009. 2009 Talent Management Fact Book: Best Practices and Benchmarks in Talent Management. Oakland: Bersin & Associates.

Byham, W., and P. Weaver. 2005. Multisource (360) Feedback That Effects Changes in Leaders’ Behavior. Pittsburgh: Development Dimensions International.

DDI (Development Dimensions International). 2003. The Impact of DDI Assessment Centers. Pittsburgh: DDI. (Revised 2007.)

———. 2008a. Leadership Forecast 2007–2008. Pittsburgh: DDI.

———. 2008b. Leaders in Transition: Stepping Up, Not Off. Pittsburgh: DDI.

———. 2009. Global Leadership Forecast 2008–2009. Pittsburgh: DDI. http://www.ddiworld.com /pdf /globalleadershipforecast2008-2009 _globalreport_ddi.pdf.

DDI (Development Dimensions International) and Economist Intelligence Unit. 2008. Growing Global Executive Talent: High Priority, Limited Progress. Pittsburgh: DDI and Economist Intelligence Unit.

Tabak, Lawrence. 2007. If Your Goal Is a Success, Don’t Consult These Gurus. http://www .fastcompany.com/ magazine/ 06/cdu.html.

About the Authors

Tacy Byham, PhD, is a manager in Development Dimensions International’s Executive Solutions Group. She provides consulting across organizational strategic talent needs, including talent strategy, talent management, talent assessment, development planning, and executive development. She is currently managing the launch of Business Impact Leadership, a new development system for midlevel leaders that ensures the action-oriented alignment of leaders relative to organizational business imperatives. Her research received the national ASTD Dissertation Award at the International Conference and Expo in 2007.

William C. Byham, PhD, is chairman and CEO of Development Dimensions International. He founded the company 40 years ago to help organizations make better hiring, promotion, and management decisions, and the firm continues to be internationally renowned in human resources consulting. He has forged important innovations in HR that have had an impact on organizations worldwide. As a best-selling author, he continues to write books and articles and deliver speeches on important management advancements and how they are affecting businesses.