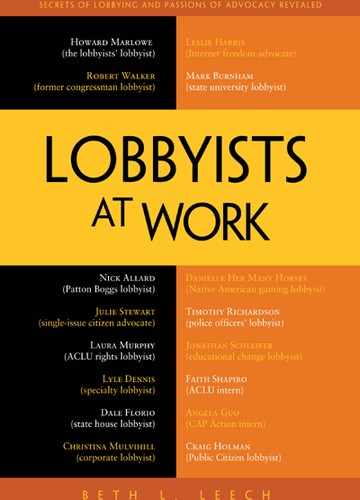

Leslie Harris

President and CEO

Center for Democracy and Technology

Leslie Harrisis the president and CEO of the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT), a nonprofit organization that advocates on behalf of Internet freedom. CDT was part of the 2012 efforts to derail the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA)and the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA), which CDT argued would have chilled online innovation and expression. CDT educates and speaks out on issues related to online freedom of expression, online privacy and security, intellectual property, and Internet architecture and openness.

Harris has been named one of Washington’s “Tech Titans” by The Washingtonian and was listed as one of “10 Female Tech CEOs to Watch” by The Huffington Post. She is a senior fellow at the University of Colorado’s Silicon Flatiron Center for Law, Technology and Entrepreneurship.

Before joining CDT in 2005, Harris ran her own public interest consulting firm, Leslie Harris & Associates, which represented nonprofits, foundations, and tech companies on issues related to the Internet. She was chief legislative counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union and public policy director at People For the American Way. She has a bachelor’s degree in sociology from the University of North Carolina and a law degree from the Georgetown University Law Center.

Beth Leech: This book is called Lobbyists at Work. Do you even consider yourself a lobbyist?

Leslie Harris: Well, not as the public understands that term. It’s unfortunate that the term has become a pejorative label, used principally to refer to people who make lots of money representing large corporate interests seeking tax breaks or earmarks. “Bridges to nowhere” and the like.

I’m also not a lobbyist as defined by current law, although I have been at various points in my career. I’m a lawyer and an advocate for policy issues that I care about. As a result, I have spent much of my career testifying in front of Congress, drafting bills or amendments, commenting on rules, and supporting or opposing bills and amendments. So how I would describe myself is as a public interest lawyer and a civil liberties and Internet freedom advocate.

Leech: Earlier in your career, you were officially a lobbyist. How did you start your career? Did you start off wanting to be a policy advocate?

Harris: No, I started out wanting to be a lawyer, probably a civil rights lawyer. I grew up in the South. I was a child in Atlanta during much of the most visible civil rights movement activity. My synagogue was bombed when I was a small child because of the civil rights activities of our rabbi. Later, I was inspired by books like To Kill a Mockingbird and activities that the ACLU was involved in, including a lot of the landmark voting rights cases. I saw myself in that work and could imagine my career path emulating that work, but it was a pretty inchoate desire. There weren’t many lawyers that I knew, and none who were women.

My high school counselors also were very discouraging about the idea of my becoming a lawyer. They believed that nobody would hire me. And as far as wanting to be a policy advocate when I grew up—that didn’t occur to me because I didn’t know any policy advocates. Today’s high schools have a lot of organized advocacy groups for high school activists, but that simply wasn’t the case back then, at least in the South.

Leech: So in high school you thought you wanted to be a lawyer but you were discouraged from it. Did you go ahead with that plan anyway?

Harris: I didn’t see that path forward. I don’t come from a professional family. I was encouraged to go to college—that was the big goal. But that was about it. I didn’t start moving into advocacy work until after college, when I came back to Atlanta from North Carolina. Atlanta had elected its first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, and Jimmy Carter was still governor and both of them were aiming to make progressive change.

As I look back, I didn’t have a plan, just a set of issues I cared about, with civil rights and women’s rights at the top of the list. I know people with master plans. I was not one of those people.

I got a job with the Corrections Department out of college. Governor Carter had brought in a reformer to lead the department. They were developing drug and alcohol intervention programs and programs dealing with sexual abuse in the women’s prison. I was a junior person working within these programs. It wasn’t advocacy, but it was reform from the inside.

After that, I went to work for the city council when Mayor Maynard Jackson was first elected. Again I was an inside person, not an outside advocate. I was a very junior person working on issues like police brutality. I started to meet people and get involved in local organizations. The National Organization for Women [NOW] was still a young organization, and I got very involved in the local chapter. I was part of the effort to set up the first battered women’s shelter in Atlanta. We were advocating for the Equal Rights Amendment before the Georgia Legislature.

Leech: That was a hard haul, I’ll bet.

Harris: I didn’t know what I didn’t know. We would invite these legislators to lunch and talk about whether they would support the ERA. They would address me as “little lady.” I find it kind of laughable now. You have a lot of courage when you don’t know anything.

Leech: That’s actually pretty inspiring.

Harris: Kind of goofy.

Leech: That’s why we like young people, right?

Harris: It’s why I love young people. But back then, I wasn’t the slightest bit sophisticated.

I really found my voice through NOW. I discovered that I could speak, that I had a voice, and that people listened. I was shaped by the injustice I saw around me as a child. I had no outlet for that, and suddenly I found myself making speeches. And I was good at it.

I became thoroughly involved in the emerging civic life of the local community, which was very vibrant. It was the beginning of what we believed would be the New South. It was in the couple of years leading up to Carter’s election as president, and it was the beginning of a new black-white coalition in the South, and Atlanta was where that was all happening. And so I was at meetings and events with John Lewis, Julian Bond, and all these people who had been my heroes.

Most of my early experiences as an advocate were around women’s rights. I started to feel empowered and I started to see a path forward, although at that point, it was not very specific. It did eventually lead me to law school. But first, I was the associate director of a rape crisis center.

Leech: You were involved in a lot in those early years.

Harris: The rape crisis center was one of the first in the country. We did training for other rape crisis centers in the South. I was doing the traditional rape counseling, training, and management. But I was also the person responsible for policy, working with the city council and the state legislature to try to reform rape laws.

Leech: So you were already working as a policy advocate.

Harris: I was doing it then and I was doing it in my work for NOW. I was doing policy on the other side of the table in all of my just-out-of-college jobs. I was just starting to see the place that might work for me. So I came to Georgetown University to go to law school.

Leech: How many years was it before you headed to law school?

Harris: I was twenty-six when I went to law school. I picked Georgetown because it was in Washington, DC, with lots of interesting work. I worked my way through law school. It was very difficult. I should have opted for the four-year evening program. But at the time, I believed I needed to “catch up” with my peers who went to law school right out of college. I didn’t want to spend an extra year. But I did have some interesting jobs.

I worked for the Justice Department for a long time. I also worked for Chuck Morgan, who had been the head of the ACLU in the South during its halcyon civil rights days. He had a small firm in DC and I worked for him for a year on a big case. I learned a lot.

I had a lot of fire in the belly for the issues that I cared about. At that point, women’s issues were number one. And I suppose if you’d asked me what I was going to do when I went to law school, I fully expected to join one of the emerging small law firms that were mostly women who were doing a lot of the early litigation and representation around employment and emerging women’s issues. That’s what I would have predicted. One lesson here is—don’t predict.

Leech: Well, even if the prediction is accurate, by the end of your career, you may be someplace different.

Harris: My favorite quote has always been, “To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive.” It’s Robert Louis Stevenson.

Leech: You went to law school, and after you graduated what happened?

Harris: I had this terrific offer to stay in the Justice Department in the Honors Program, and I had an offer from a terrific law firm. The law firm—Wald, Harkrader and Ross—was known for its commitment to pro bono work and its stellar leadership. I chose the law firm. My entering class at the firm was the first one with an equal number of women and men.

I discovered fairly early on that even though these were some of the most extraordinarily interesting, and bright, and wonderful people in Washington, that I just couldn’t make myself care about a lot of the work. For me, my legal skills had to be placed in a context of something I cared deeply about. I really struggled with it. I was not sure what I was going to do, and I saw a job posting for the ACLU and I applied. I didn’t expect to hear from them. I was two years out of law school. But I did.

There are moments when roads diverge and you have to make a choice. The ACLU offered me the job and, frankly, I panicked. People just didn’t leave a prestigious law firm after two years. I persuaded myself that I needed to stay at the firm. I wasn’t sure I was ready for risk, so I turned down the offer. The board member who called me, the late Jim Heller, actually got quite angry and said to me, “Fine, go have a nice, safe life.” I was stunned, but I thought about his words all night, and called back early the next morning and accepted. I remember saying, “You know, Jim, I don’t want a nice, safe life.” So that’s how I joined the ACLU. I am forever grateful to him.

I had a great career at the ACLU for thirteen years. Most of that time was spent in the Washington office, which is basically the legislative and policy arm of the national ACLU, and I did a lot of good, old-fashioned lobbying. But it was at a time where Congress was less partisan, more productive, more open to working across the aisle. I worked on several important civil rights bills. I led our efforts against the nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court and against the constitutional amendment on burning the flag. I worked on a range of reproductive rights issues, the death penalty, habeas corpus, free expression, religious liberty, and more.

Leech: I had initially thought that you were in the litigating arm of the ACLU.

Harris: I was never a litigator. I worked on cases in the law firm and when I worked for the Justice Department, but I was not a litigator for the ACLU.

I worked on critically important issues, learning how to navigate Congress, develop bipartisan support, and bring together coalitions. Being a good lawyer and a trusted source for members and staff mattered. But being a good strategist was equally important. I was lucky to have wonderful mentors, including Morton Halperin, whom I still rely on for advice all these years later.

Leech: The way you describe your interactions with Congress suggests that perhaps things are different now.

Harris: It is different now. It’s much more driven by party politics. Pre-9/11, it also was a more open environment. Back then, if it was late at night and something you were working on was being debated on the Senate floor, you and other lobbyists would be right there, standing in the Senate antechamber or at the door to the House floor, places I haven’t been in years. At a key moment, the senator, or staff, or both would come out to discuss what was happening and how to respond to possible amendments or other developments. I had to understand strategy as well as the substance of the issue. I had to know how to create coalitions around issues and powerful messages. It took inside knowledge about how Congress worked and the rules for floor debate. Today, almost every bill that comes to the Senate faces a filibuster and there need to be sixty votes to get the issue on the floor to start the discussion.

In those early days, a filibuster meant that the senator stayed on the Senate floor and talked. I can no longer remember the issue, but I recall bringing a civil rights casebook to the late Senator Paul Wellstone to read on the floor during a filibuster. He stayed all night and so did we.

Leech: That’s interesting.

Harris: I was lobbying on the Hill at a time when there were a lot of important civil rights and civil liberties issues. I had an opportunity to contribute to a lot of them and learn an enormous amount about how to be an advocate—how to be a principled advocate. By that I mean advocacy grounded in intellectual rigor, deep expertise, and a respect for the facts, not just the message. And I’m very grateful for those years. They were really important and fun.

I also had a lot of opportunity to appear before the media. I am not sure young people have the same opportunity to learn media skills as I did. They learn to blog and tweet, but there are fewer opportunities to be in front of a camera and make your point. But when you are called on to debate Rudy Giuliani on a crime bill on Crossfire when you are three years out of law school, as I was, you have to learn to do it. Broadcast and cable media today rely less on substantive expertise and more on political partisans.

Leech: Interesting. Where are we in your story? You’ve been at the ACLU. Why did you decide to leave?

Harris: First, the Clinton administration came in and I worked in the Clinton Justice Department transition. It seemed like the right time for my own transition and I had an offer from People For the American Way to head their public policy shop. I was there about three years. Again, I had great experiences. I played a lead role in drafting the law that protects women’s access to abortion clinics. I was part of the leadership of the Campaign for Military Service, which was the coalition fighting against Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. And I was part of the leadership of the coalition fighting against the Communications Decency Act.

At the same time, I became fascinated by the Internet and its capacity for free speech and democracy-building, as well as its potential power as an advocacy tool. There were seminal questions about whether the Internet would be available to low income and rural communities, which led me to play a leadership role in a coalition that successfully advocated for a new universal service program that subsidized Internet access in schools and libraries. It was an early program to address the digital divide.

I also saw that many of the questions and many of the issues that I had worked on for a number of years were going to get played out again over this new technology. It was too early to understand that it was going to be a platform for everything. We thought it would be a platform for democracy and for equal opportunity. We didn’t know it was going to be a global platform for human rights. I became intrigued and discovered my inner geek. I was already an early adopter of technology—largely because the guys I worked with at the ACLU all had computers.

Leech: They were there.

Harris: And I knew then that computers were one more thing the guys were going to get that the girls weren’t, and so I joined in to see what it was about.

So my interest goes back a long way. In the mid-1990s, we were starting to see that the new technology raised equality issues and access issues as well as free expression issues. We did not yet fully realize how important privacy and government surveillance issues would be in this new space. No one at the time completely understood what the Web would be. Once again, I took a risk and left People For the American Way to set up my own firm.

It was one of the first consulting groups to focus on the Internet and new technologies, and probably one of the first founded by a woman. We were mission-driven—our mission being to harness the power of the new digital age for social good. We did some lobbying, for example, on free expression issues for the American Library Association—including Patriot Act issues, new content-filtering laws, and new questions coming up about intellectual property. We also represented groups like the National Center for Accessible Media at WGBH on disability and technology issues and educational technology groups on emerging issues and funding.

But Congress was not the only place that these new issues were emerging. For example, the question of how to make the Internet accessible to people with disabilities was facing companies as well. My firm worked with America Online to create a disability advisory council to look at new products and services. We also helped forge a partnership between the company and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights to build their technology capacity and to explore the potential value of the new technologies to the mission of member organizations.

Leech: So your advocacy, in part, was between and among organizations, not necessarily organizations-to-government?

Harris: Yes, I helped foundations learn and develop programs in the area. I did some direct coalition building and management for foundations as people started to work in this space. And I built partnerships between industry and nonprofit groups. I also began to represent clients before agencies like the Federal Communications Commission.

Leech: How does one go about building these coalitions?

Harris: I had no idea where to begin, but many people I had worked with over the years either became clients or opened the door to them. For example, one of my colleagues at People For the American Way went on to join AOL, eventually leading its Washington office. She reached out to me on a specific policy project and introduced me to the AOL Foundation, which was looking to build partnerships with communities I had worked with for years.

I realized that I had this enormous network and it was gratifying to discover that my firm had something valuable to offer them. It was an incredibly diverse portfolio, but the thread that tied it together was technology and the public interest.

What I resisted doing during those years, and what I think I needed a break from, was being a very visible public advocate. I really enjoyed the break from that. It takes its toll. But the firm thrived for about ten years and had ten employees at its peak.

Leech: So when you did leave your firm, you came to CDT?

Harris: Yes. CDT was created by people who also came out of the ACLU.

Leech: I did not realize that.

Harris: Yes. CDT’s founder, Jerry Berman, was one of those guys at the ACLU who were already into the policy implications of technology when the rest of the world didn’t know what a desktop computer was. I was always close to the organization. I headed CDT’s public interest advisory group back when I was still at People For the American Way. I ran that group with John Podesta, who later created CAP [Center for American Progress], and who earlier was Clinton’s chief of staff.

And so I was very close to the organization as an advisor and consultant. My firm did a couple projects here and there for CDT. And when Jerry retired, CDT approached me about the job and I was ready to get back in the game.

When you’re an advocate in Washington you’re always putting yourself out there, and that was true even before people were 24/7 on Twitter and Facebook. But being an advocate is always being in the public eye, with testimony, media, speeches, debates, and constant meetings.

At my lobbying firm, even though we were very active and I had ten employees, I actually backed away from public visibility so that I had some flexibility in my schedule. It was a strategy for how to deal with life during ten years when my children were growing up.

Leech: A nanny can’t do it all, right? Nannies can’t go to ballgames.

Harris: Well, they can—and mine sometimes did. But I didn’t really want to have someone else do that for me. Some people do, and that’s fine. I just know what worked for me. But when my children were older, I was ready again for a big challenge in taking a very good organization to its next level. There were nine people at CDT when I joined. We’re now around twenty-five. We have offices in California and Brussels. And the issues are really interesting and compelling.

Leech: So, could you explain in a nutshell the mission of CDT?

Harris: The mission is to keep the Internet open, innovative, and free. That’s the world’s shortest mission statement to be sure. But what that means in practice is that we aim to ensure that the technical, legal, and policy framework for the Internet continues to provide for an open platform for free expression, democracy building, and innovation. To do that, we have a team of lawyers, policy professionals, and technologists.

Leech: What sorts of things do you do to try to fulfill that mission?

Harris: We support measures to increase online privacy and believe the United States needs to enact a comprehensive privacy law. Having said that, it is hard to get it right in an environment where innovation is fast outpacing law. That is why we also work with companies to ensure that privacy is built into the design of products and consumers have more tools to control the use of their own data. At the same time, we are fighting against surveillance and increased data collection that violates privacy and security.

We work on intellectual property and we were a very major part of the big uprising that happened last winter against SOPA, a bill that would have imposed a variety of obligations, including blocking and filtering content—something that we just don’t do in the United States. Of course, we work on traditional free expression issues. We also work on Fourth Amendment privacy issues related to surveillance, cybersecurity, and national security. The Patriot Act years were very busy and I have to say not as successful as I would have liked. We bring a lot of expertise to the table. We’re asked to testify a lot. We draft analyses and reports and participate in agency proceedings. We’re called by congressional offices, the FCC, the FTC, the Departments of Commerce and Homeland Security, and other agencies to come talk to them about issues. We convene diverse parties around issues to find consensus. We are often asked to serve on agency advisory committees. We don’t do that much lobbying.

Leech: Because if they ask you, then it’s not lobbying.

Harris: Well, it’s more complicated than that. But we keep our hours very carefully to determine whether we have reached the threshold for lobby registration.

Leech: Where does your concern about not getting to the point where you’d have to register as a lobbyist come from?

Harris: Part of the concern comes from the limits on the amount of lobbying that 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofits can do, and part of it comes from the complications and restrictions associated with being a registered lobbyist, owing to the many scandals involving corporate lobbyists over the last decade—think Jack Abramoff.

It’s become a very difficult situation to navigate. The public interest advocacy community has been hurt by being herded into the same cattle pen with the enormous corporate interests. The work public interest advocates of all political stripes do is constitutionally protected. We are supporting citizens’ rights to petition the government. I worry that has been lost in the debate.

Leech: In the case of the Stop Online Piracy Act, how did CDT first become involved?

Harris: We first became involved at least a year and a half before it became a big public issue, when there was a similar but more narrowly written bill introduced in the Senate. One of the first things we did was to meet with Judiciary Committee staff about what our concerns were in the bill language.

Leech: And how had you heard about the issue in the first place?

Harris: In this case, I am pretty sure that Senator Patrick Leahy’s office had asked us to look at the bill. But it’s a big community. Long before that bill was introduced, drafts of the bill were circulating among the advocates and companies who work on intellectual property and Internet policy. It’s really hard for me to say how we first knew about it.

In this case, we were in strong disagreement with Senator Leahy. We have worked with the senator on many civil liberties and Internet matters over the years, so it would not be surprising for his staff to reach out and get our views early. And we had enormous problems with the early drafts of that bill.

CDT is known as an organization that has a lot of expertise. And so our first action is not to go to the press. Our first action is to write a short, understandable, serious memo on what’s wrong with the bill and try to make sure that a lot of people see that memo quickly, including the office involved. So we wrote a memo and shared it broadly with other organizations, companies, and congressional offices that were interested in the bill.

Looking at that bill, and especially its treatment of domain policy, we saw concerns about security. We saw concerns about free expression. We saw concerns for the rest of the world in terms of how global content would be treated in the United States and what kind of precedent it would set, particularly in the developing world that hasn’t really established policy around the Internet.

So then we did a lot of outreach. We reached out to the top technologists and security experts who we thought would share our concerns about how the bill planned to block domain names. We reached out to human rights groups. We reached out to intellectual property advocates, to domain name registrars and experts, and to Internet companies. There are a lot of different communities, and we weren’t the only people at that point to sound the alarm. But our involvement began very early on.

At that point, there wasn’t really a lot of grassroots involved in it but there was a very active coalition in Washington that was working on the bill. It seemed unlikely that we would be able to stop the bill, so one of the strategies was proposing lots of amendments to try to narrow it. But members of our coalition also were talking to other members of Congress to try to get somebody to object. And that somebody turned out to be Senator Ron Wyden. So there were lots and lots of meetings with other members of the Judiciary Committee to express concerns, and then with other members of the Senate who were known for caring about civil liberties on the Internet.

Leech: How often do you end up working in coalition with other organizations in the work that you do at CDT?

Harris: An enormous amount of our work is in coalitions, both formal coalitions and informal working groups. We facilitate several ongoing working groups at CDT focusing on consumer privacy, freedom of expression, and government national security/civil liberties issues in which advocates, academics, and companies participate. Those groups are one of the places that our work gets shared and discussed. But on this issue in particular, another organization, Public Knowledge, coordinated the loose coalition around intellectual property.

Leech: And so when a coalition like this comes together, how often do you meet?

Harris: At least weekly, and as things heated up, much more. There was a lot of thinking about who else needed to be involved to slow the bill down. The first iteration of the bill didn’t move at all in the Senate. It came back in a slightly different form and moved out of committee without a hearing involving any civil liberties or Internet advocates.

CDT held a press briefing early on, which lead to a few editorials, articles, and analyses, and some of the key bloggers picked up the story and started writing about it. This is a full year before SOPA and PIPA became national news and lots and lots of people became involved.

When the bill came to the House Judiciary Committee, the circle began to widen. There were efforts in New York and in Silicon Valley to start bringing the venture capital community together and getting more technology companies involved in the bill. And that was when the important online campaign began to come together.

So the circle started getting wider and there started to be venture capitalists who came into town to meet with members of Congress about their concerns with the bill. People from our coalition went to the White House quite a few times over the course of a year and a half to meet with different people about our concerns. Because the administration did not have a position on the bill at the beginning, the White House was an important target for advocacy—particularly regarding cybersecurity concerns.

There were a lot of meetings and discussion about what the bill might potentially look like, but it took the House a very, very long time to come up with the bill. We didn’t like the bill in the Senate, but at least Senator Leahy was open to talking to us about our concerns and making changes. In the House, they wrote a bill but would not show it to people or get any kind of feedback from outside. I think the House bill was so bad that it finally started a drumbeat that developed over time as more and more influential bloggers talking about the bill and writing about the bill. Then people started talking about it or reading about it on Reddit and other social media spaces, building strong interest outside of Washington. And it was at that point that grassroots groups and DC advocates began to join together in the effort that led to the online campaign and the Internet blackout.

Leech: Oh, very interesting. And during this time, what was CDT doing?

Harris: It was no-holds-barred at that point. CDT was writing and working with the online activists as well as the DC-based opponents. We were building resources for the grassroots who were developing their own campaign, putting together an online resource that mapped the growing opposition to the campaign, and participating in endless meetings on the Hill, including regular strategy meetings with key Congressional opponents. There were meetings in the White House, as well. CDT was also working with technologists on an influential report, taking them around the Hill and encouraging companies to get involved.

Leech: That’s interesting that you needed to encourage them. Historically, computer and Internet companies were known for not being politically involved and not really being super-savvy about Washington. They assumed that if there were an issue that affected them, they would be asked by the committee for their opinion. That assumption seems to have changed.

Harris: Obviously, the big companies have a presence in Washington now, but a lot of companies still tend to work through their trade associations so that they don’t have to visibly take aggressive positions in Washington. That’s partly the culture, but it’s also good politics. Nobody wants to be in an aggressive position opposing the chairman of the committee. But soon there was a deluge of opposition from engineers, entrepreneurs, companies, and activists.

Leech: So CDT was essentially acting as a think-tank and as a resource?

Harris: I would not say think-tank. We were certainly lobbying and participating in the development of the strategy. But CDT has a particular voice and that voice comes not just from the advocacy position that we believe in, but from our expertise. That’s kind of our brand. We were the expert resource for a lot of what was going on in the grassroots at that point.

Public Knowledge did a great job of being the resource on the policy process itself: “Here’s what happens in committee. And here’s what it means when amendments are offered.” What CDT would add is expertise on how the technology works and how particular legal obligations would play out in practice. We talked about what the implications would be for Internet users and for companies.

In November 2011, the first grassroots call-in day was organized, where constituents would call their members of Congress to express opposition to the bill. CDT’s basic memo explaining what the bill would do was downloaded thousands of times that day.

Leech: Wow. Was your server ready for that?

Harris: No, but it survived. And on then the big Internet blackout day—January 18, 2012—a number of sites, including Google, had links to some of our key resources. I was very afraid that the amount of traffic was going to bring our site down entirely.

There are people who spend a lot time arguing about which role is most important: grassroots, inside strategy, or outside strategy. I just don’t see things divided like that. I see them as highly integrated and, if they’re done right, each part of the advocacy campaign plays a role that strengthens every other part of the campaign. Full credit needs to go to a whole set of people who ran that online campaign, who did a completely brilliant job. And it built from the initial work that was done for the previous year and half here. I would never pick any one piece of the big campaign and say it was because of this piece or that piece that the legislation was defeated. I don’t believe that’s ever true.

Leech: Including the Internet blackout.

Harris: Oh, the blackout was critically important. But it didn’t happen in a vacuum. It happened in conjunction with a set of senators who had already said they were going to filibuster the bill. It happened in the climate of a press that was, by now, highly educated about and hostile to the bill. It happened in the context of analysis that was widespread and heavily read about what the implications of the bill were, and a technologists’ report that set out the security dangers. But the blackout was critically important. Do I think that’s why the White House took the position it did against the bill? I know it wasn’t, but I also know the blackout forced them to finally act.

Leech: Why do you think the White House took the position they did?

Harris: They were very, very worried about cybersecurity implications, but I think their number-two concern was global Internet freedom. And there were hundreds of thousands of people around the world protesting this bill, because they knew that if the United States were to start blocking and filtering Internet content, something we have never done, that it would be “game over” for the rest of the world. We would have no moral authority to fight for global Internet freedom.

And so the administration had a lot of crosscurrents. It is an administration that has strong beliefs in protecting intellectual property and with strong ties to Hollywood—so they certainly didn’t do it for political reasons. Whoever they made happy, they also made a lot of people unhappy. And I was pleasantly surprised to see that at the end of the day, traditional politics didn’t block them from saying what they believed to be true. They came out with their position over the weekend before the blackout.

Leech: Before the blackout.

Harris: Yes, but everyone knew that there was going to be a tsunami unleashed the next day. There are many different pieces to a successful campaign. And in an Internet environment, there is no command and control: there’s only consultation. There were so many different elements. There was a very high-level meeting at the White House that brought in CEOs and top-level people from industry, which I participated in. That was very important in terms of White House thinking. So there were just too many pieces, all happening at once, to be able to claim which moment in a series of moments was the one that somehow won it. The blackout was critically important, that is clear. And I think the blackout also has created an opportunity for a much broader set of individual organizations and companies to work together on these issues. That’s probably the best thing that’s come out of it.

Leech: I’d like to have you walk me through what your average day looks like. And given that I’m guessing there is no truly average day, maybe you could pick a day last week and tell me how it went.

Harris: Well, I tend to come in the office early because I don’t like to stay as late as a lot of my staff. Remember, I run this organization, so there are a lot of things I have to commit my time to every day that are not terribly fun: fundraising and management take up a fair amount of time. I check my e-mail every minute, so I can’t say there’s a time to check my e-mail.

Leech: Got it.

Harris: I would love not to do that, but I do. I also usually run upstairs pretty regularly, because we’re on two floors. I call it “making rounds.” CDT has grown dramatically over the last five years, so we have to work to remain cohesive and keep the culture of a small organization.

There is no such thing as an average day, so let me look at my calendar and tell you some of the things that happened last week. On Monday, CDT held a press briefing in our office on Internet governance related to an upcoming treaty renegotiation at the International Telecommunications Union. We are playing a lead role in organizing several groups around the world in understanding and reaching out to their own governments on this issue.

So fairly early in the day, we had a press briefing. Since it was Monday, we also had a staff meeting, which gives us a chance to catch up with each other and try to figure out if there’s an issue that we ought to be discussing—either on the Hill, in a regulatory proceeding, or something in the news about what a company or a country is doing. It’s not unusual for us to pull together internal meetings to discuss what our position might be on an issue that’s arising. On Fridays, we reserve lunchtime so that people can get together to try to do that kind of meeting.

Then last week, the Senate cybersecurity bill was about to come out, so we had a pretty long meeting to discuss the substance of the amendments that were being offered to address the privacy concerns that we had, and the complicated question about what our position should be on the bill. We were successful in getting a lot of important changes. So did we still oppose the bill? What were we going to say to the grassroots groups? What were we going to say to the sponsors of the bill?

Later in the afternoon, I had a fundraising meeting. If I wasn’t running the organization, I might be lucky enough to be purely an advocate and not have fundraising meetings. But I have lots of fundraising meetings with funders and potential funders.

I went out to a State Department meeting where they wanted some advice about an Internet conference, and who should attend and what issues they might suggest to the country that was hosting the conference for countries from all over the world. My schedule is going to disappoint you because I haven’t been on the Hill in the last few weeks.

Leech: Well, that’s good to know. Sometimes advocacy is not only about the Hill.

Harris: Actually, I don’t go up there very much.

I spent a couple of hours writing a keynote speech that I was going to be giving at a conference. We’re hiring a CDT director in Brussels, and I spent about forty-five minutes to an hour talking about candidates and résumés for that job. Then I had another meeting at the State Department. This is not all in one day. I’m just trying to give you some ideas.

Harris: There’s not a lot that’s moving in Congress because it’s an election year and things tend to shut down. So, except for the cybersecurity bill that’s moving ahead, there’s not a lot of legislative activity. Agencies continue to have proceedings, but by summer in an election year, it does slow down here.

Another day, I had a meeting at a company where they wanted to get our view on a new product they were rolling out and how they were trying to protect privacy. They wanted our feedback and suggestions as to whether or not we thought they were doing the right thing. We actually do a lot of that.

Leech: What sorts of products would you be asked to consult on?

Harris: In this case, it had to do with the collection of people’s personal data and what kind of protections they’re putting on that data. Are they going to hold on to that data? Are they going to share it with third parties? The fact that the Internet is driven by an advertising model makes this a constant and very big issue.

Leech: That’s interesting that you consult with these companies. Is that something you do as part of your advocacy, or is that also a moneymaker for the organization?

Harris: It’s part of our advocacy. We advocate with companies because what they do in this space has a lot of implications for people’s privacy and rights to free expression. I should be clear here that we are funded in part by companies who participate in our working groups. We believe in consultation and dialogue, and working toward consensus where possible.

The other thing that would happen in the course of a week is that one of our working groups would meet. For example, we have a Digital Privacy and Security Working Group, so our director of that project and the people who participate in that working group—advocates, companies, technologists, and academics—might get together around something specific—like the cybersecurity bill—or around a longer-term goal. For example, a major priority is reform of government access laws because the government has much easier access to your personal information online than it does offline. What you store in your desk requires a warrant. What you store online in your social media, or e-mail, or search browsers often does not.

So we have put together a very big coalition to try to amend the law, which includes advocates from across the political spectrum and a growing number of companies. The senior lawyers here who are project directors are focused all day every day on whatever issue is in front of them. They’ll be on the Hill. They’ll be meeting with other groups. They’ll be drafting memos. They’ll be drafting amendments. That’s basically what I did for a very long time. But it’s not necessarily what I do when I’m running an organization.

I spend a lot of time going back and forth among my projects, checking in, offering advice, seeing where work that’s being done on one issue overlaps or has a potential to conflict with work that’s going on in another issue. And there’s a lot of staff management, hand-holding, and conflict resolution.

Leading the organization has a different set of activities and a fair amount of high-level luncheons and meetings with government officials and people who lead other organizations and people in companies. It’s about relationship-building and looking for opportunities to work together. And raising money.

Leech: Your day would wrap up usually about when?

Harris: It really depends. I’d say six thirty is average for me, but that doesn’t mean I don’t go home and just start up again. I’d say almost every night I’m working, and I tend to work most Sundays, although not all day. But it really depends. This time of year, it’s a lot slower. And people tend to have different biorhythms. If I have a lot to do, I’ll start working at six in the morning. The younger staff will work at twelve at night.

Leech: Are most of your younger staff lawyers?

Harris: There are a lot of lawyers. We have technologists—mostly people with master’s degrees or PhDs in computer science from the information schools. Some people have a lot of experience doing policy, but are not lawyers. We also have a communications team, including a person who is managing social media, and a director for campaigns.

Leech: Let’s focus in particular on the people who do policy. If you’re hiring someone like that, what are you looking for in that person?

Harris: We don’t have the opportunity to train people who don’t know anything about this area, so almost everybody who comes into CDT is either going to have a strong civil liberties background or, if they’re coming out of law school, they’ve already taken lots of courses and shown a strong interest in the issues that arise from the Internet. They’re going to have to be really, really good writers and thinkers.

Leech: And why in particular is good writing important?

Harris: Because it’s part of our brand that we are producing understandable memos, issue briefs, and blogs that people in positions of authority can take and use and have trust in when they’re making policy decisions. Part of our brand is making sure that when people look at our work, they say: “This is serious work done by serious people and we can rely on it.” So, writing skills are important.

Leech: What else are you looking for in that person?

Harris: The person needs to be highly creative because there isn’t one reliable way that the policy process always operates. There isn’t a beginning, middle, and end that always happens.

A passion for the work is really important. You can’t do this kind of work without caring about it and having a reason for doing it. You really have to care about how technology intersects with civil liberties. It’s not the kind of job you just come into to produce documents. You have to be excited. You have to care. And, of course, almost everyone comes in to CDT with a strong grounding in technology.

Leech: What advice do you have for someone who would like to be a policy advocate?

Harris: Get a good education and start with what you care about. Volunteer or do internships in relevant organizations. If you are in college, look at ways to be involved in the organizations that exist on campus. For people who are interested in coming to Washington, a lot of people start on the Hill.

I never did spend time on the Hill. Also, Washington is not the world. It is an interesting place to work, but there are real trade-offs between trying to work in an advocacy organization here versus one in a city. I started my career working in a city. In a city, you know everybody, and you get to see the fruits of your labor a very direct way. I think it’s much harder when you work in the national level.

There is a difference between wanting to do politics and wanting to do issue advocacy, and Washington is as much about politics as issue advocacy. So if you can’t stand the politics going on all around you, this is probably not the place to do advocacy.

The most important thing is to know what you care about. There’s no such thing as “I want to be a generic advocate.” I think that’s meaningless. What do you have passion for? What do you want to achieve in the world?

So I think people should think really broadly about what they care about, what their skill set is, and what the different venues are to work on the issues they care about. Washington is a really interesting place to be, but it’s not the world.