Chapter 2

Getting Through to the Inner Core

We all clearly have the ability to hear something being said but not let the message reach into the central core of where we reside. One way of referring to this special inner core might be the command from center of our brains. Through some yet‐to‐be‐fully‐understood series of mechanisms, incoming messages can be totally blocked and are DOA: dead on arrival. Alternatively, some can be partially blocked, such that we hear only what we want to hear, and others can be allowed inside fully intact, as is.

The point is that nearly everyone in our life wants access to our inner command center because that means they have the opportunity to influence the decisions we make. The innermost you is sought after by parents, teachers, coaches, religious leaders, politicians, employers, family members, TV advertisers, and on and on. Entry into your command center means the door to changing your thoughts, your behavior, and your choices is open.

Here are some examples of blocked messages:

- A father tries to convince his son not to use recreational drugs, but the son subconsciously blocks the messages from reaching his inner core. As the father is speaking, he realizes his words are having little or no impact on his son.

- A mother constantly tells her older children to attend church on Sunday. They hear her words, but the words are blocked from reaching their inner core.

- A wife continually conveys, verbally and nonverbally, that the lack of emotional safety she feels in the relationship is eroding her trust, and the marriage. Her message is dismissed and ignored.

- A couple agrees to a free trip in Las Vegas in return for attending a time‐share sales class. Both hear the persuasive presentation but both prevent the information from penetrating their inner command center. They do not purchase a time‐share unit.

- A high school teacher persistently sells her political ideology in her classes. Some students are able to completely prevent her political persuasions from entering their inner control center.

- A husband attempts to convince his wife that she needs to be more sympathetic and encouraging with their two boys in competitive sports. His message falls on deaf ears.

- A best friend tries to convince his buddy to exercise more regularly to lose weight. The friend is 100 pounds overweight. The heartfelt words go nowhere.

- It's time to buy a new car but upon arriving at the dealership, you are confronted by a very pushy, overly dramatic salesperson. You hear all of his words but nothing he says connects with you. You leave the dealership and vow never to return.

Here are some examples of being granted open access to someone's command center:

- For whatever reason, I fell hook, line, and sinker for everything she said. I ended up making some terrible choices.

- I instantly liked the salesperson at the dealership. I found myself really trusting almost everything he recommended. I ended up buying a car that was too expensive and the wrong color. I have deep buyer's remorse.

- I've always trusted my friend so when she encouraged me to try some drugs, I agreed. I have so many regrets about that first decision.

- Most of my friends find ways to cheat on tests. They convinced me to do the same and now I'm cheating too.

- I went on a week‐long Outward Bound trip with my dad. For the first time in years, I started hearing what he was saying to me. I really was headed in the wrong direction.

- I get the same feedback from my colleagues at work every year. For some reason, this year's survey results really got to me. I'm sincerely trying to make changes.

- I love and trust my coach. I do everything he tells me without hesitation.

The Gatekeeper

Here are a couple of important questions: First, what is the connection between decision‐making and one's command center and, second, what is the process by which access to our inner command center is granted or denied? The answer to the first question is that one's command center represents the location where decisions are actually made in the brain.

The answer to the second question is more complicated. Clearly there are some criteria, whether conscious or not, for determining which messages are let through and which are blocked. With that in mind, let me reintroduce you to Y.O.D.A. This is not the YODA of Star Wars but there are some similarities. As we learned in Chapter 1, this Y.O.D.A. stands for Your Own Decision Advisor.

Here are some wise decision insights:

- Y.O.D.A. is the senior resident in charge of our command center. We all possess a Y.O.D.A., but there are vast differences in effectiveness and good counsel.

- Y.O.D.A. represents our inner resident coach and master decision maker.

- Y.O.D.A. is an acquired competency that continues to evolve throughout life, a skill that can be intentionally built and strengthened, just like any other muscle.

- Y.O.D.A. can be a blessing or a curse, depending on the advice given.

- To be your best advisor possible, Y.O.D.A. should be preloaded with critical life coordinates such as core values, beliefs, and core purpose in life.

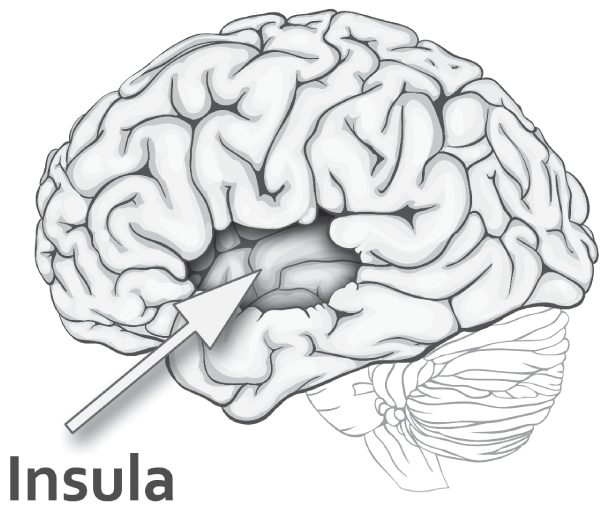

- The exact neurological location of Y.O.D.A. is still in question but the human insula appears to be a major contributor. (See Figure 2.1.) Hidden deep within the sulcus of the brain, the insula subserves a wide variety of functions, ranging from sensory and emotional processing to high‐level cognition. The insula processes visceral sensations, autonomic reactions, somatic and auditory processing, decision‐making, attention control, cognitive functions, and speech. Although neuroscience has not found a single place where decisions and self‐awareness are located in the brain, the insula clearly plays a central role.

- Y.O.D.A. is highly trainable and is the primary target of this book. Your own resident advisor holds the keys to extraordinary decision‐making.

Figure 2.1 The insula.

The Blocking and Tackling of Decision‐Making

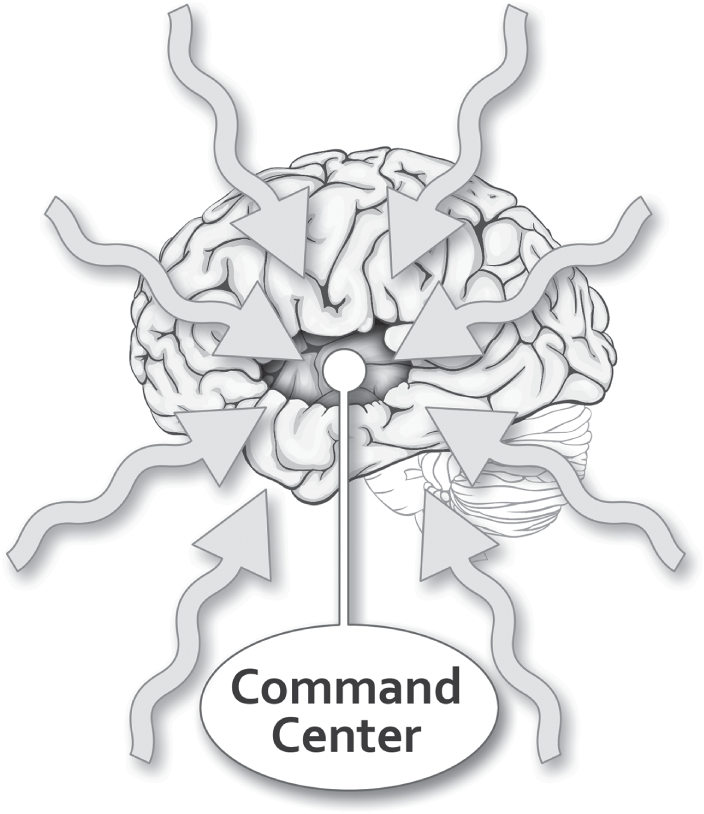

Whether you are blocking information from getting through to your brain's central command center (holding your defensive line) or are tackling a difficult decision and trying to get it right, the neuro‐processor between your ears is receiving neural signals from multiple areas of your brain. (See Figure 2.2.)

The neurological footprint of every decision is different and entirely unique. Even your effort to block information from getting through to your inner core represents a decision, whether conscious or subconscious. Prior to every decision, neurons send coded messages through sudden bursts of electrical signals. We make decisions based on the cumulative sum of all related neurological inputs, both positive and negative. Most decisions, both blocking and tackling, are made quickly and subconsciously based on previously acquired habits.

So the big question is: Where did the acquired habits come from and how were they formed? Were they intentionally acquired and do they actually support responsible and wise choices? Most people report little understanding about how or when habits were formed, habits that play such a pivotal role in the day‐to‐day choices we make. An important objective of this book is to change that. Rather than allowing the process of habit formation to occur automatically without reflection, a consciously determined vetting process for decision‐making will be detailed in Chapter 5. Once the vetting process guidelines are clearly established, the next step is to automate that process itself. Converting that process into a habit occurs with regular, intentional practice. Once habituated, all decision‐making will automatically be screened through a predetermined set of lenses you put in place.

Figure 2.2 The command center.

To better illustrate how the fine‐tuning of the habit acquisition process occurs, let's use the example of shooting a basketball. The decision to take the right shot occurs in milliseconds, but the learning process occurs gradually over time. An important element of coaching basketball is teaching players good decision‐making habits around shooting. Helping players learn when to take a shot and when not to represents an important aspect of successful coaching. When players first start playing, the decision to shoot is haphazard and undisciplined. Gradually, players begin learning what constitutes a good versus a bad shot‐making decision. Considerations such as distance from the basket, the position of the defender, time remaining on the clock, the player's shot‐making competency from different distances, and their mental and emotional state are intentionally and consciously used to improve shot‐making decisions. With repeated practice and feedback from the coach, the entire process eventually becomes automatic and instinctive. Taking the right shot at the right time, regardless of whether it is successful, becomes an instantaneous decision requiring little or no conscious deliberation.

Some decision‐making lends itself to being completely automated, occurring without conscious deliberation, while others do not. Things like shooting free‐throws in basketball, eating healthy foods, exercising regularly, or always being 10 minutes early for appointments can, with training, be converted into habits. Other decisions, however, require measured consideration. Momentous decisions fall into this category. Examples might include: Should I get a divorce? Should I have a complete shoulder replacement? Should I get a second vaccine booster shot? Should I put my daughter on anti‐anxiety medication? Some decisions require days and even months of vetting to get to the right decision.

An interesting decision‐making scenario is deciding what to order from a restaurant. Some people scan the menu and can decide very quickly, whereas others struggle to decide what to choose. They often wait for everyone to order and may even ask others what they think the best choice for them would be. If vetting habits around food selection have already been acquired, deciding what to order from the menu is vastly easier. Qualifiers might include considerations like low‐fat, small portion size, dairy‐free, vegan, gluten‐free, and the like. Once the vetting process is acquired, making the right choice can occur nearly instantaneously.

Here are some wise decision insights:

- Every person possesses an inner core where decisions are processed. For the purposes of this book, this will be referred to as the central command center.

- The command center is capable of receiving a vast array of neurological signals from geographically dispersed regions of the brain in decision‐making. Such inputs are critical in making sound decisions.

- Cutting‐edge neuroscience suggests that the human insula plays a central role in the command center's operation.

- Everyone wants access to the inner core of a person, because that opens the door to influencing a person’s choices.

- Human beings are capable of consciously or subconsciously granting or denying access to the command center of their brains.

- Some decisions are completely under the control of habit and require little or no deliberation. Others (such as which member of your family should be chosen to act as executor of your will) require thoughtful and careful consideration.

- Whether conscious or not, our brains are referencing something in granting or denying access to our command center as well as in making the right decision. An important objective of this book is equipping Y.O.D.A. with a consciously designed vetting process for both.

- Converting the vetting process to a well‐established habit that automatically surfaces whenever important decisions are to be made represents the final step in ensuring better and more responsible decisions.

Sources

- Banas, J., and S. Rains. “A Meta‐Analysis of Research on Inoculation Theory.” Communication Monographs 77, no. 3 (2010): 281–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751003758193

- Beutler, L. E., C. Moleiro, and H. Talebi. “Resistance in Psychotherapy: What Conclusions Are Supported by Research.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 58 (2002): 207–217.

- Bonetto, E., J. Trian, F. Varet, G. L. Monaco, and F. Girandola. “Priming Resistance to Persuasion Decreases Adherence to Conspiracy Theories.” Social Influence 13, no. 3 (2018): 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1080

- Cautilli, J. D., T. C. Riley‐Tillman, S. Axelrod, and P. N. Hineline. “Current Behavioral Models of Client and Consultee Resistance: A Critical Review.” International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy 1 (2005): 147–154.

- Cautilli, J. D., and L. Santilli‐Connor. “Assisting the Client/Consultee to Do What Is Needed.” A Functional Analysis of Resistance and Other Forms of Avoidance.” Behavior Analyst Today 1 (2000): 37–42.

- Conway, K. “Encoding/Decoding as Translation.” International Journal of Communication 11 (2017): 18.

- Craig, A. D. “How Do You Feel—Now? The Anterior Insula and Human Awareness.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10 (2009): 59–70.

- Ecker, U. K. H., S. Lewandowsky, B. Swire, and D. Chang. “Misinformation in Memory: Effects of the Encoding Strength and Strength of Retraction.” Manuscript submitted for publication, 2010.

- Fein, S., A. L. McCloskey, and T. M. Tomlinson. “Can the Jury Disregard that Information? The Use of Suspicion to Reduce the Prejudicial Effects of Pretrial Publicity and Inadmissible Testimony.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 23 (1997): 1215–1226.

- Frederick, S. “Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19, no. 4 (2005): 25–42.

- Gilbert, D. T., D. S. Krull, and P. S. Malone. “Unbelieving the Unbelievable: Some Problems in the Rejection of False Information.” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 59 (1990): 601–613.

- Gilbert, D. T., R. W. Tafarodi, and P. S. Malone. “You Can't Not Believe Everything You Read.” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 65 (1993): 221–233.

- Greene, E., M. S. Flynn, and E. F. Loftus. “Inducing Resistance to Misleading Information.” Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior 21 (1982): 207–219.

- Luntz, F. Words That Work: It's Not What You Say, It's What People Hear. New York: Hyperion, 2007.

- McCabe, D. P., and A. D. Smith. “The Effect of Warnings on False Memories in Young and Older Adults.” Memory & Cognition 30 (2002): 1065–1077.

- McDermott, K. B. “The Persistence of False Memories in List Recall.” Journal of Memory & Language 35 (1996): 212–230.

- Messer, S. B. “A Psychodynamic Perspective on Resistance in Psychotherapy: Vive la Resistance.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 58 (2002): 157–163.

- Patterson, G. R., and P. Chamberlain. “A Functional Analysis of Resistance During Parent Training.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 1 (1994): 53–70.

- Rohini, A. “Examination of Psychological Processes Underlying Resistance to Persuasion.” Journal of Consumer Research 27, no. 2 (2000): 217–232.

- Saywitz, K. J., and S. Moan‐Hardie. “Reducing the Potential for Distortion of Childhood Memories.” Consciousness & Cognition 3 (1994): 408–425.

- Seamon, J. G., C. R. Luo, J. J. Kopecky, C. A. Price, L. Rothschild, N. S. Fung, and M. A. Schwartz. “Are False Memories More Difficult to Forget than Accurate Memories? The Effect of Retention Interval on Recall and Recognition.” Memory & Cognition 30 (2002): 1054–1064.

- Uddin, L. Q., J. S. Nomi, B. Hebert‐Seropian, J. Ghazi, and O. Boucher. “Structure and Function of the Human Insula.” Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 34, no. 4 (2017): 300–306.

- Van Denburg, T. F., and D. J. Kiesler. “An Interpersonal Communication Perspective on Resistance in Psychotherapy.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 58 (2002): 195–205.

- Warren, A., K. Hulse‐Trotter, and E. C. Tubbs. “Inducing Resistance to Suggestibility in Children.” Law & Human Behavior 15 (1991): 273–285.

- Watson, J. M., K. B. McDermott, and D. A. Balota. (2004). “Attempting to Avoid False Memories in the Deese/Roediger–McDermott Paradigm: Assessing the Combined Influence of Practice and Warnings in Young and Old Adults.” Memory & Cognition 32 (2004): 135–141.

- Westerberg, C. E., and C. J. Marsolek. “Do Instructional Warnings Reduce False Recognition?” Applied Cognitive Psychology 20 (2006): 97–114.