10

Implementing Systems

In this chapter, we focus on monitoring growth and impact as you implement your strategic plan. Given the foundational work you put into the needs assessment and planning process, it is critical to ensure that strategic initiatives lead you toward your instructional vision. Creating robust feedback loops and being transparent about growth will ensure that you will continue to shift your systems to ensure that your district is truly in support of all students. The chapter concludes with a case study of a district that was able to make considerable growth toward its vision as a result of their commitment to MTSS.

Avoiding the Fate of Sisyphus

There is an old adage, “practice makes perfect.” We have heard that from countless teachers and coaches, and you know what? They were lying. Neither of us has achieved perfection in anything, regardless of how much we persisted. It is probably more accurate to say that practice makes progress, and we believe that wholeheartedly. But we want to add something to the mix. It's not enough to practice and persist. You also have to monitor progress; otherwise it can feel a little like you're working way too hard and not getting results. And there is nothing more frustrating than that.

As former English/language arts teachers, we are both reminded of the Greek myth of Sisyphus. As the myth goes, Sisyphus ticked off Zeus, and his punishment was to roll a boulder up a hill for all eternity. Regardless of how much he practiced and pushed, that boulder rolled back down. We hear from too many educators and leaders that they feel the same way—they are practicing, pushing, and persisting but aren't making a considerable impact on student outcomes. This is why implementing practices and programs with fidelity and creating a culture that monitors progress is critical. Both of these components are absolutely essential, but too often, the concepts have a negative connotation in schools and districts.

You walk into a meeting of educators and start using the words fidelity, integrity, and data‐based decision‐making, and you may observe some awkward body language. We know this work is about kids, not numbers, but the evidence is clear. If we want to positively impact the outcomes of all students, there are known practices, programs, and interventions that give educators and students the best chance of success. Using words like fidelity and data helps to support educators because, let's face it, a lot of the work about what works has been done for us!

When we lean into fidelity and integrity, we provide a recipe for success. The reason we monitor progress is simply that we do not want teachers to push a boulder up a mountain all year to find out after 180 days that they are right back where they started. Punishments from Zeus are no joke, and our educators deserve better.

Unpacking Fidelity

Implementation fidelity is the degree to which a program, practice, or intervention (from herein, we will refer to all as intervention) is delivered as intended. Fidelity checks should create open communication and productive feedback by providing educators and leaders with opportunities to learn and collaborate (Dane and Schneider, 1998; Gresham et al., 2000; Sanetti and Kratochwill, 2009). Often, implementation fidelity is used to discuss what happens in classrooms, but in our work implementation fidelity also relates to district and school improvement efforts on a larger scale. First, let's unpack why monitoring implementation fidelity in classrooms is critical.

If implementation fidelity is not consistently monitored, researchers caution that teachers and students are stuck in a black box and may struggle to understand why students aren't making progress. As Smith, Finney, and Fulcher (2017) noted, “Inside this black box could be the intervention as it was designed or intended or an intervention that deviated from what was intended.” Leaders can help to paint a picture of intervention fidelity by working with teams of educators to co‐create implementation fidelity data. Evaluators and coaches must examine five components of implementation fidelity data on an ongoing basis related to teacher practice (Smith, Finney, and Fulcher, 2017):

- Specific features and components of the program

- Whether each feature or component was actually implemented (i.e., adherence)

- Quality with which features and components of the intervention were implemented

- Perceived student responsiveness during implementation

- Duration of implementation (i.e., the amount of instruction provided, which typically includes the number of sessions and the length of each session)

We love the work of researchers Erica Mason from the University of Missouri and Dr. R. Alex Smith from the University of Southern Mississippi. In their article Tracking Intervention Dosage to Inform Instructional Decision Making (Mason and Smith, 2020), they share an anecdote about the importance of monitoring quality and duration:

Consider how the different causes of the student's unresponsiveness would warrant different instructional responses. If it were determined incorrectly that the intervention was not successful, a teacher might needlessly make significant modifications to the intervention materials, practices, or content or select a different intervention altogether. On the contrary, if it were determined that the student was missing intervention time, a teacher might conference with the student's family or seek the support of colleagues in getting the student to intervention on time and minimize disruptions (p. 94).

Once individual teachers understand implementation fidelity data, leaders can use the data in their own professional learning communities (PLCs) to drive instructional improvement. Note how evaluators and coaches can use the questions that follow as they support educators in implementing evidence‐based interventions.

- What are the features and components of the intervention that all teachers need to implement?

- How will we know if they are implementing all features and components with quality?

- How will we respond when teachers are not implementing all features and components with quality?

- How will we collaborate with teachers who use all features and components with fidelity to scale the intervention throughout the school or district?

These examples are focused on classroom‐specific implementation, but we also need to monitor the implementation fidelity of our MTSS efforts. When focusing on building a multi‐tiered system, there are three basic types of fidelity. These three types of fidelity are generated from the categorized fidelity work in Table 10.1:

Table 10.1 Fidelity categories.

| What Is Fidelity? | What Are the Fidelity Categories? |

|---|---|

| Fidelity is the degree to which the program is implemented as intended by the program developer, including the quality of implementation. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from NIRN https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/module-1/usable-innovations/definitions-fidelity last accessed January 10, 2023.

- Context: Fidelity of implementing the critical components of a multi‐tiered system of supports (MTSS)

- Consistency: Fidelity of using the problem‐solving process across all three tiers

- Competency: Fidelity of implementing evidence‐based instruction and interventions matched to specific need(s)

To determine adherence, we need to select multiple sources of data. For example, to answer the question “How will we know?” we may examine classroom observation data, student outcome data, and staff self‐assessment data. Table 10.2 provides examples of each of the fidelity categories and the kinds of products that can help determine fidelity.

We can monitor the fidelity of implementing the critical components of equitable MTSS by continually returning to the needs assessment work, the self‐assessment, our logic model, and our action plan. The self‐assessment (shared in Chapter 7) was designed to allow teams to look at their readiness for MTSS grounded in deeper learning. Although it is encouraged to use this tool in the exploration stage to inform the planning stage, teams may wish to use it to monitor their progress throughout implementation.

Table 10.2 Fidelity categories and associated artifacts.

| CONTEXT Fidelity of implementing the plan | CONSISTENCY Fidelity of using problem‐solving processes and structures | COMPETENCY Fidelity of implementing evidence‐based instruction |

|---|---|---|

| Reviewing Policy and Procedures Procedural review protocols and the fiscal review protocols are designed to help teams regularly review policies, procedures, or practices to assess how well aligned they are to plans. | Assessing Educator Evaluation Establish a SMART goal protocol to vet educator evaluation goals so that they are actively working to support student outcomes identified in your plan. | Using Content‐Based Observation Tools For example, create English/language arts Look‐For Guides for observing classroom content and practice. |

| Reviewing Systems These are resources that can be used on an annual basis to assess systems related to your plan and are content‐specific and systems driven. This may be a literacy system assessment or an equity review. | Assessing Data‐Based Decision‐Making Create a data use self‐assessment tool to assess the overall programmatic use of data, or a data dashboard checklist to be used to assess specific data practices. | Program Review Tools Adopt features of a structured Foundational Skills Checklist to evaluate classroom/school/district's approach to foundational reading skills. |

| Reviewing Materials Create materials to help you review the fidelity of key areas articulated in your action plan. For example, develop a protocol for assessing bias in your instructional materials or use defined databases to assess the effectiveness of existing assessment screening tools for the specific students you serve. | Assessing Professional Learning Utilize a UDL PD rubric to assess professional development implementation against the UDL framework. | Planning Review Tools Create an instructional planning guide with tools such as a UDL Lesson Plan Review Template to assess individual lessons or a UDL Course Assessment to assess full courses for alignment with UDL. |

| Reviewing Turnaround Practices Use level‐specific rubrics to assess the implementation of turnaround practices related to your current plan. | Assessing Student Schedules to Create a Master Schedule Review tool that includes a series of reflective questions about the master schedule to support leaders in evaluating schedules with an inclusive lens. | Using Instructionally Based Observation Tools Use the UDL Look‐Fors (Appendix A) or design a set of Inclusive Practice Look‐Fors to assess planning materials or conduct classroom observations to give feedback to staff. |

The fidelity of using the problem‐solving process across all three tiers requires an ongoing data culture. The following considerations can be helpful as you identify implementation data points to monitor improvement efforts.

- Determine the data needed to monitor and evaluate key aspects of the implementation process, such as communication and feedback loops and professional development activities (outputs).

- Determine data needed to evaluate intervention effectiveness, including performance assessment, fidelity, and the emergence of desired outcomes.

- Determine the data needed by teams, trainers, coaches, practitioners, and any other individuals for decision‐making.

- Determine the capacity of the current data system and make additions and improvements.

Fidelity Checks in Practice

Often, schools deliver professional development to staff but then do not have systems in place to follow up on whether all staff are utilizing the practices effectively. It is important to predetermine and regularly apply fidelity checks to ensure that evidence‐based practices are integrated and sustain the system of support. Regularly assess that:

- Evidenced‐based curriculum and instructional systems exist.

- A valid and reliable assessment system (screening and progress) operates throughout the year and clear data‐based decision‐making rules are implemented.

Table 10.3 provides a sample throughline of a SMART goal and its fidelity measures: By June, the school will develop a comprehensive assessment map and calendar, define a data tracking system, and use monthly data meetings to support written intervention plans for all students scoring below the 35th percentile on i‐Ready, as measured by a completed map, student data, data meeting minutes, and meeting artifacts.

Feedback Loops

Feedback loops are the practices and procedures that monitor your progress to ensure that you're moving toward your vision. Feedback loops are cycles designed to provide school leadership teams with information about implementation barriers and successes so that a more aligned system can be developed to meet the goals outlined in an action plan. Feedback loops aren't just about data. While the data will help measure progress toward student outcomes, it is also critical to have feedback systems to find ways to improve professional development and the organization as a whole.

In many cases, the feedback loops are how you will become aware that some people are resistant to the change and will need additional support and information to feel more secure moving forward. Too often, the measures we use to assess our progress are not construct relevant. Simply, we do not measure what we intend to. If you use the logic model and action planning templates in Chapter 9 and you continue to monitor progress and report status updates, you can avoid this common mistake.

Table 10.3 Excerpt of a sample action plan for SMART goal with identified fidelity steps and measures.

| Strategy/Action | Personnel Responsible | Measurement | Inputs/ Resources | Timeline | Fidelity Steps and Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regularly scheduled grade‐level data meetings | ELA supervisor, principal | Meeting agenda, notes, and intervention plans that result in increased student outcomes in all literacy measures | Provide professional development on creating a data culture. Schedule time for data meetings. | Monthly | Conduct a periodic review of meeting minutes and intervention plans and review against assessment data. |

| Create literacy data tracking systems for all students | ELA Supervisor | Completed and updated data tracking systems | Student assessment database. Time for ELA supervisor to enter all available data. | Updated two times a year (BOY and EOY) | Assess the data dashboard against tiered support models to ensure appropriate staffing and scheduling are available to meet student needs. |

The purpose of teacher professional development is to increase teacher efficacy and improve teacher practice with the ultimate goal of increasing all learners' outcomes, particularly those historically marginalized. Therefore, true measures of professional development are teachers' increased feelings of efficacy, changes in instructional practice, and increased student outcomes. Too often, however, the quality of professional learning is measured by a simple survey asking teachers if they were engaged and if they would recommend the presenter.

This is not to say that these are not important questions, but they do not provide schools and districts with the data and feedback they need to determine if the PD is doing exactly what it is meant to do. Robust feedback loops, therefore, begin with clear targets and ongoing reflection on progress toward those targets so you can share meaningful status updates with your school community.

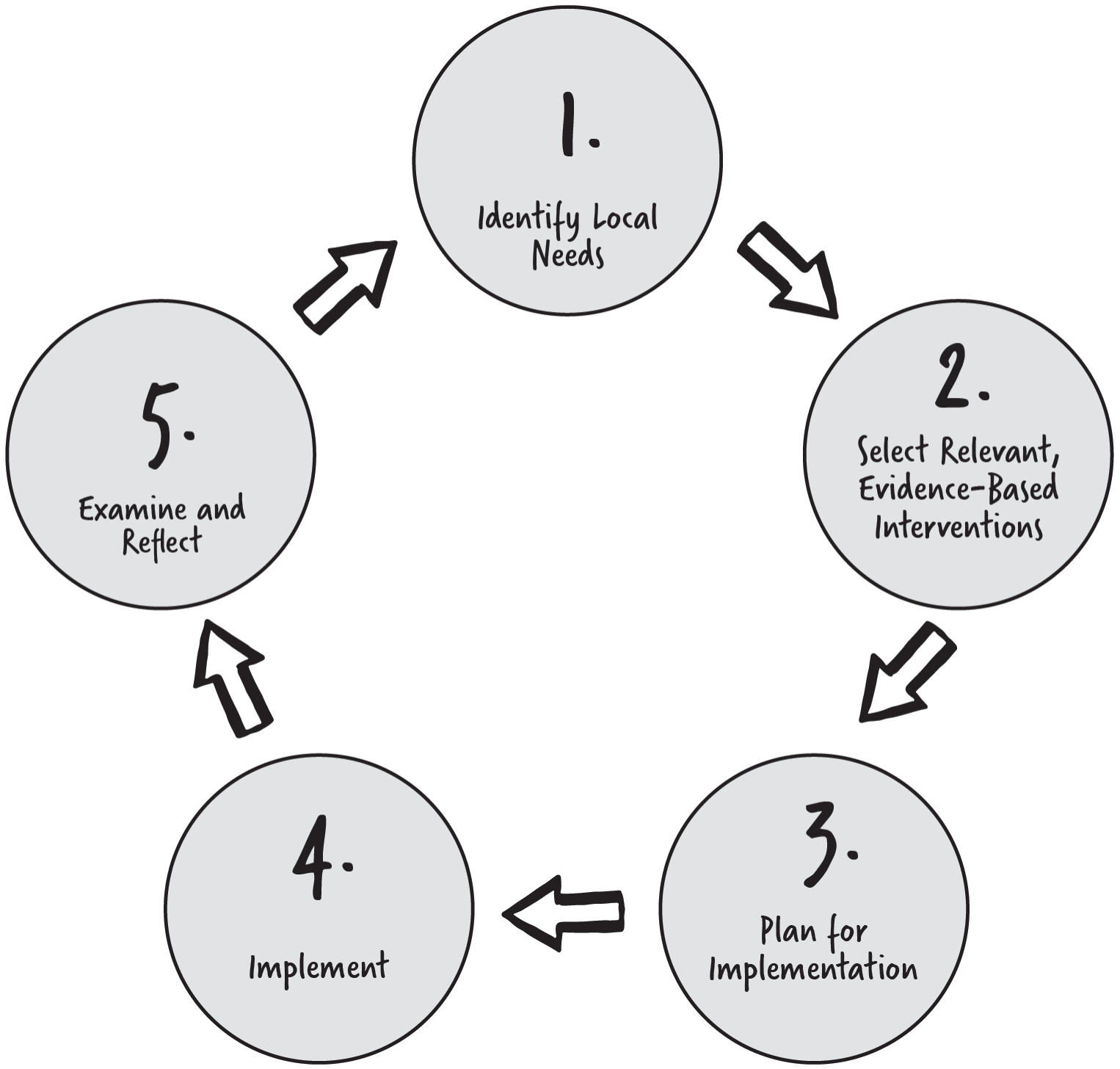

This process is outlined in the guidance for the Every Student Succeeds Act. Figure 10.1 presents a visual for feedback loops, shared in a publication from the US Department of Education (2016). The steps in the process for continuous improvement, when taken together, can support better outcomes for students.

As you continue your MTSS journey, be sure to continually review multiple forms of data in a cycle of feedback to enhance program effectiveness and meet/exceed the outcomes of all students. In each cycle, the feedback loop can be likened to the research process, commencing with the formulation of a research question, “Is our action plan effective in increasing the outcomes of all students?” and moving through the iterative phases of data collection, analysis, and reflection. This process is ongoing and is reiterated many times (Venning and Buisman‐Pijlman, 2013). To simplify, feedback loops consistently answer the following questions:

- What are our goals?

- Where are we now? (What are your barriers and successes?)

- What do we need to do next to eliminate barriers and optimize success?

Once you determine which sources of feedback you will collect on a regular basis, begin to incorporate feedback loops into your meeting agendas. Having these questions at the beginning and the end of the meeting (or protocol) ensures that the feedback loops are on the agenda.

Figure 10.1 Feedback loop cycle.

At the beginning of every planning team meeting, ask:

- Is there any follow‐up communication from the previous meeting we have made of others?

- What new sources of feedback do we need to review? (Data meeting minutes? PD surveys?)

- Have any stakeholders requested our input, support, or problem‐solving?

At the end of each agenda, ask:

- Is there information we need to communicate to others who have requested our input, support, or problem‐solving?

- Is there any more information we need to provide input or support?

- How will we share our analysis of feedback and how will that impact our next steps?

The most important part of a feedback loop is where it often falls short. Sharing any insights or findings with your entire school community is critical to keeping the cycle of feedback moving. Determine how you will communicate the analysis of feedback.

- Meet monthly with your MTSS advisory group?

- Will you have a planning team newsletter?

- Present at each faculty meeting?

- Have representatives on the core team met with stakeholder groups?

Having effective feedback loops keeps all stakeholders engaged and invested in their work by making them feel valued by the team. As you build your MTSS, you will invest time and energy in collaboration with multiple stakeholders. Don't lose the connection and the energy once your plan is done. The collective effort of creating the plan is just the beginning. As you continue to work toward your vision, you must go through this process again and again until you realize that vision for every single student.

We do this work because we believe, without exception, that every single student can learn at high levels and access deeper learning when we get the conditions right. Those conditions require us to change our mindsets, our skill sets, and above all, our systems. We have to commit to changing classroom instruction, our tiered supports, and our systems. This work is possible. We want to end this book with a story of a district we worked with, partnering with them throughout their initial MTSS process. Know that this growth is not only possible but probable if you commit to this journey.

A Case Study: Integrating MTSS

This case examines how a regional district in Massachusetts integrated MTSS by addressing instructional methods, tiered systems, and systems and structures. A core team made up of central office administration, building‐based administration, coaches, and teacher leaders began this work in 2016.

The team contracted with us to receive training on inclusive practice and UDL. In addition, the team conducted a book study of our book Universally Designed Leadership (Novak and Rodriguez, 2016). Throughout our work, we supported them to complete a document review, data analysis, and root‐cause analysis.

In their approach, one key finding was that Tier 1 instruction was not inclusive of all learners in terms of placement, access to instruction, and outcomes. In response, the team created a focused multiyear professional development plan aligned to the goals in the district's strategic plan to increase inclusive opportunities and outcomes for all learners within an equitable MTSS.

Multiple layers of offerings were created to support early adopters and those with previous experience with the implementation of inclusive practices. Scaling the work was also prioritized to consistently increase the baseline and implement a plan for supporting new teachers. Differentiated opportunities were provided for professional development that was designed for all educators (paraprofessionals, specialists, teachers, administrators) based on clearly defined goals. In addition to required professional development, supplemental professional development was flexibly designed based on educator interest, availability, and capacity.

Professional development included keynote presentations on inclusive practices for opening day, full‐day workshops, instructional rounds, presentation of information at faculty meetings, book studies, provision of resources to include webinars and written materials, mini‐institutes, lab classroom opportunities, and a graduate course series in UDL. All offerings were based on the vision and goals of increasing the inclusivity of instruction to improve student outcomes.

To fund the coaching model, the district prioritized coaching as a high‐leverage structure. Decisions were based upon the prioritization of the model. The district aligned the high school and middle school schedules to increase the ability to share staff, resulting in the ability to reduce positions through retirements. In addition to the funds reallocated from these reductions, Tier 1 access for all learners in content areas was prioritized with co‐teaching models. This shift to inclusive instruction through co‐teaching resulted in a reduction of paraprofessionals. The district did an analysis of all staffing ratios to ensure they were adequate to support rigorous instruction but also foster independence and access to Tier 1. The coaching model in the beginning stages included a full‐time coach in K–8 and a part‐time coach in K–12 science.

The district used data to allocate these resources, given they were limited in relation to need. Purposeful, data‐based feedback loops resulted in making changes midyear to reallocate coaching supports to areas of need. Additionally, two building‐based principals who had previously been identified as “teaching principals” were restructured to be coaching principals. As teaching principals, they were focused specifically on providing Tier 2 instruction to a small group of students relative to the overall population. As coaching principals, they were able to impact all learners through coaching in classrooms using coaching cycles with the goal of strengthening Tier 1 instruction to reduce the need for remediation in Tier 2.

Following the first year of implementation, growth was evident in the data where coaching had been implemented. The administration used this data to propose the addition of a full‐time instructional coach at the elementary level, and a coaching vice principal of teaching and learning at the middle school level. The district also reallocated staff to create a coaching position at the high school. The science coaching was reassigned to the elementary instructional coach, increasing the time available to the high school. The two coaching principals remained, rounding out the team. The coaching team meets regularly to look at data, engage in professional development, and receive support from the assistant superintendent of teaching and learning.

In 2019, three years into their strategic MTSS plan, all five schools increased their accountability and criterion‐referenced score on state assessments. The district's middle school, the only school in the district that was identified as being a “turnaround” school by the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, exited turnaround status within one year. Specifically, the school increased the percentage of targets met from 8% in 2018 to 77% in 2019.

Take a moment and consider the strategic moves this district made as it built a robust MTSS. Table 10.4 outlines their actions based on the MTSS model for deeper learning.

Table 10.4 MTSS strategic moves of case study district using equitable MTSS practices.

| Component | Strategic moves |

|---|---|

| Tiered Systems: Data‐Driven |

|

| Systems and Structures: Staff Development and Competency |

|

Summary

Creating an equitable MTSS rooted in deeper learning is an extensive process that is evidence‐based, reflective, and cyclical. Ultimately, the work is grounded in a vision of equity for all learners. For too long, our systems were designed for the mythical average learner and did not embrace learner diversity or variability. Instructional strategies, tiered systems, and structures did not serve many learners, including our students of color, students with disabilities, students from economic disadvantage, and our multilingual learners. Every one of these learners is capable of greatness, but it requires our systems to shift priorities and make the complex changes necessary to shift the outcomes and experiences of our learners. Throughout this text, we have shared a process for better seeing your current system and recognizing what needs to change in order to achieve both equity and inclusion. Now that you have a plan, you must continue this process, continually looping back to determine how your system and structures provide a pathway for every learner to be exactly who they are, and successful in deeper learning experiences that allow them to work toward mastery, identity, and creativity.

Reflection Questions

- What does it look like to successfully lead an inclusive and equitable school district? What measurements are you using in your district to monitor your progress?

- As a team, you will determine what systems you have in place to record and track the data metrics you have chosen for district/school improvement. Where will you record the data and how will you share it? What systems (such as your existing student information system) do you have to house this data? Is it robust enough? If not, what next steps are necessary?

- As you reflect on your journey in this text, answer the following question: What is equitable MTSS and how does it support all students?