Chapter 3

The Queen's Gambit: Translating strategy into tactics

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.”

– Sun Tzu

The room is silent. You could hear a pin drop and there's a collective hush. In the centre of the space in a pool of light, two men sit at either side of a chessboard. All the perfectly carved black and white pieces are lined up neatly on the chequered board.

One of them is Magnus Carlsen, a Norwegian chess grandmaster who holds the record for the longest unbeaten run in classical chess and who is currently unbeaten in over two years of competitive play. His opponent is the relatively young Polish grandmaster Jan-Krzystof Duda.

The game begins with both men staring intently at the board and occasionally making notes as the game progresses. Each player takes pieces from his opponent, with both deliberating over their moves. As the number of pieces on the board decreases and the game edges closer to a conclusion, you can feel the tension in the air. Eventually, Duda has it and Carlsen faces his first defeat in 125 games.

Even with all of his experience, knowledge, and foresight, Carlsen was beaten by a relatively junior chess player in professional terms. This just goes to show that, despite being masterful at turning strategy into tactics, things can come out of left field and surprise even the most seasoned and experienced of us.

Chess grandmasters can hold more than 20 potential future moves in their head, but they don't ever consider more than four to six moves ahead because they don't know what their opponent is going to do. They know that there's no point in thinking 24 moves ahead because their opponent's response is going to change what they do. They always have to respond to the opposition.

Within chess there are already many, many options; and each of those options comes with more options. When you factor in what your opponent does, this adds a further layer of complexity to those variations.

However, a regular chessboard is two-dimensional, which means that you can see everything that's happening. You have a view of the whole board and can begin to map out your strategy, even if you know that might need to be altered based on what your opponent does. For businesses, the reality is more like the game of three-dimensional chess that appears in Star Trek.

This board has multiple levels, some of which are moveable. If you look at it from above, it looks very similar to a standard chessboard, but you can't plan your strategy in this game by only looking down on it. You are playing across different levels; you can move certain platforms depending on the strategy you're following, and so can your opponent. You have to look at the board from multiple angles; a piece on level one can still take a piece on level three, for instance. Adding this third dimension brings yet more complexity to the game, even though you are fundamentally still following the rules of chess.

Playing three-dimensional chess is therefore closer to how businesses operate in the modern world. There is an element of unknown, you might not be able to see everything at once and you may have to test the waters at times to make sure you're covering all bases.

Thirty or 40 years ago, being in business was more akin to playing traditional chess. Many businesses were fairly one dimensional in that they would set out a strategy and follow it. In the modern world, with new technology, and customer habits and preferences evolving, businesses need multiple strategies. Those strategies need to be tested simultaneously, which we talk more about in Chapter 4, and you need to be in a position to rapidly course correct when necessary.

In business, you are playing chess in multiple dimensions and you can't afford to play from the top any more. You'll have multiple strategies and be making decisions that have short-, medium-, and long-term effects, so it becomes harder and harder to know what to do next.

If you're going to do something, do the right thing

In the previous two chapters we've talked about the importance of having that big vision and purpose for an organisation, and how measuring the right metrics can ensure everyone is aligned on how to achieve that vision. In this chapter we're going to look at the importance of doing the right thing and not jumping to conclusions about what that right thing is.

But what is the right thing? There isn't a single answer to this question, but as Jeff Bezos says, a good place to start is customer obsession. Making the shift from positioning products in the minds of customers to being relevant in the lives of customers is the key.

Focusing on outcomes over outputs

Many businesses focus on outputs rather than outcomes. Outputs are deliverables that don't necessarily add inherent value, such as a presentation or a piece of functionality on your website. Outcomes are tangible results that have a measurable effect on a business goal. The problem with focusing on outputs is that it doesn't necessarily move you any closer to achieving your vision. You're back to sitting on your rocking horse thinking that you're going somewhere because there is motion when, in reality, you're still in the same spot.

When you're trying to solve any problem, it's therefore important to focus on the outcome rather than the output you see. This involves considering multiple strategies with multiple outcomes to find the right one in any given situation. There are multiple routes to your outcome, the key is in deciding and prioritising which you are going to take.

Think of this journey a little bit like the challenge from the game show Takeshi's Castle where you have to run to the top of the hill while dodging boulders. Just like in business, you have your North Star (in this case the top of the hill), and just like in business, there are multiple ways to get there.

Where you hide, how you climb the hill, and the route you take might vary, but your ultimate aim will be to reach the top of the hill. You have to be agile and flexible when it comes to choosing your route: Some of the routes will be shorter; some will be longer, but result in fewer hits from boulders rolling down the hill; however, whichever route you take you are still moving in the same direction and orienting yourself by your North Star.

In Takeshi's Castle, there is another game where contestants have to run through a series of doors to reach the end of the course. Some of the doors will be blocked, some of them will be clear, and some of them will have people behind them who then chase you. Contestants have to make very quick decisions or they will end up off the course and in the water. In business, it is really no different.

You need to be able to run through doors quickly, taking advantage of the ones that are clear, but course correcting rapidly when you face an obstacle. Agility is key when it comes to making those decisions, which means moving away from a linear approach to decision making and being prepared to quickly change direction if you go through the wrong door.

Yesterday's tactics aren't tomorrow's strategy

In the past, there was more focus on personal selling, that is one-to-one between a customer and sales representative, and it was focused on the customer's need. Today, selling has become much more focused on personalisation. However, this isn't focused on customer need; instead it is about selling to people at every available opportunity and selling to people via channels rather than one-to-one. We see the future strategy for businesses being more personal as the battleground for customer experience grows.

There is an evolution happening here, which starts with what we call next best offer (NBO). This is where, as a business, you create a range of offers you think your customers want, based on what you know about them, and the next time you encounter them on a particular channel, you present them with that offer, irrespective of what that customer actually wants. In this instance, the business is doing something to the customer.

The next step in this evolution is next best action (NBA). Rather than simply selling, this involves a business thinking about what action a customer might take next. You create a range of customer journeys, drop your customer into one of those journeys based on what they're doing, and try to nudge them along that path towards what you want them to do. This is also an example of doing something to the customer.

Finally, we have next best experience (NBX). This is where, as a business, you see a customer has a need, you try to understand what that need is, and you curate what that moment needs to look like to meet that need. When you do this as a business, you are creating experiences based on what each customer needs at a specific moment in time.

However, many businesses still base their decision making around selling, which leads to what we consider a very one-dimensional approach. There is a significant focus on being personal and the commoditisation of data, which is all centred on selling and giving customers the next best offer, rather than the next best experience.

Experience is the next battleground for businesses, but we're not talking about experience simply in terms of how an app performs or how someone serves a customer. We are talking about the entire experience a customer has with an organisation or brand. Next best offer is just one subset of that experience. The whole experience battleground is considerably broader, and includes the three main stages we previously talked about, the first of which is next best offer.

This is an evolution, with each step increasing in complexity as you go.

Next best offer (NBO): We would equate the next best offer to a Rubik's cube. From any starting position, the cube can be solved in a maximum of 20 moves. There are a limited number of ways it can be mixed to give you a starting position, and a limited number of ways to solve it.

A step up from next best offer is next best action, which is where you start thinking about the next action you want your customer to take, which isn't necessarily limited to just buying a product or service.

Next best action (NBA): To continue our gaming analogy, we equate next best action to a game of chess, where there are 400 possible options after the first two moves have been taken. While this is still a finite number, it is considerably more than 20 and introduces greater complexity to the decision-making process.

However, what leading businesses are starting to lean towards is delivering the next best experience. This is where you ask, “What is the next experience I think this customer wants?” It results in a much more personal experience for each customer, which is tailored around emotional intelligence (EQ) and understanding that customer's need.

Next best experience (NBX): Within games, this is the equivalent of playing Go, a Chinese strategy game that has been in existence for more than 2,500 years. After the first two moves in Go there are 130,000 options. While still finite, this is a much closer comparison to the unlimited nature of human experiences than chess or a Rubik's cube.

Experiences are created from many moments where customers interact with brands. These moments don't all neatly connect into the customer journeys that we expect them to take. We can't plan for every eventuality because the journeys are complex and we don't always know what customers will want next.

Not everything is in your control

If you think about the game Go and how many options open up after those first two moves, you can see how the complexity of the environment you're operating in increases significantly. You can't control what moves your opponent will make, and you therefore can't completely control the direction the game takes, although you can steer it through your own moves.

When you start thinking about NBX, the options are vast. There will also be a number of factors that come into play that set outside of what you know about your customers. It's no longer as simple as looking at their browsing and purchasing history on your site to present them with similar products.

To develop a better understanding of what NBX could be for any given customer, it helps to consider the three ways in which you interact with customers: outbound, inbound, and unbound.

Outbound interactions are the ones you're fully in control of. These are communications you send out to the customer, so you're in control of the timing of that communication as well as what it contains.

Inbound interactions are the ones you receive from your customers. These are on the customers' terms and therefore can sometimes present a challenge because you won't always know when you're going to receive these or what they will contain. Sometimes it's possible to force an inbound interaction by asking customers to respond, at other times it will be a case of your business responding to whatever customers send to you. These are the interactions that significantly increase the complexity of next best experience.

Unbound interactions are the trickiest to manage because they are the elements that you as a business are unaware of and generally not in control of, but that may still have an impact on your journey with customers and their overall experience.

A good example of this is when a customer applies for a mortgage with a bank. The bank can only control so much of that customer's experience, because a customer will also be working with a mortgage broker, a solicitor, an estate agent, a surveyor, and possibly others. There are many different factors that aren't necessarily part of your journey as a brand, but that can still affect the overall experience that customer has.

What can you, as a business, do to handle all these possible permutations of a situation and still provide the next best experience for your customers? The best way to deal with this is to create a framework that is able to flex according to the myriad customer reactions you may encounter as well as those unbound interactions. Adaptability needs to be baked into every aspect of your business.

Immersive versus invisible experiences

We think of two categories of customer experiences that you, as a business, need to be aware of: immersive experiences and invisible experiences. Immersive experiences are the ones everyone sees. We all know when a brand does things to delight its customers and we're aware of them happening to us when we are a customer.

Invisible experiences, on the other hand, are the parts of a brand's offering that simply have to work, and as a customer we shouldn't necessarily be conscious of them. There is often limited measurable benefit to getting an invisible experience right, but it can come with a very costly consequence when you get it wrong. A great example is broadband – the only time you notice it is when it's not working. However, it is important to understand what the customer needs regardless of whether you are delivering an immersive or an invisible experience.

Many organisations fall into the trap of doing something cool and glossy because it is cool and glossy, rather than considering whether that particular activity meets a customer need. The key is to begin by identifying the need among your customers, and then deliver an immersive or invisible experience accordingly. You should be able to draw a line back from every experience you offer to the customer's needs that it meets.

Just like every single component of a winning Formula 1 team is deliberately designed for maximum performance, everything you design in your customer experience needs to be deliberately designed to match up with the customer's needs. Paying attention to these intricate details is what is going to produce memorable moments that add up to experiences that your customer values.

There are also nuances around the definition of a personal experience. Amazon is a company that provides its customers with a very personalised experience, but it does so in a very impersonal way with no emotional attachment. These subtle nuances in how you can approach the concept of NBX can make it very challenging to know where to begin as a brand.

“The answer is 42”

If you've read The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, you'll know that 42 is the answer at the end of the book to “the ultimate question of life, the universe, and everything.” However, in the book the question wasn't defined and therefore those seeking it needed to build an even more advanced supercomputer (the Earth) to find the question. The irony, of course, is that Earth is destroyed just before it is about to reveal the question.

If your plan is to turn motion into progress, it's a good idea to start with the question. Many businesses start with the answer and work backwards to find the question or the root of the problem. If we look at Amazon, it starts with the question: “How do I make a customer happy?” so it always starts at this point and works towards the answer. Because this is so ingrained in the business, certain things, such as refunds when a customer complains, happen automatically. This brand value drives certain behaviours and outcomes.

Finding clarity through classification

We started the first chapter by talking about the peppered moth, and we're going to return to a zoological example now. If you look at the fields of zoology and botany, there are millions of species of plants and animals on this planet. Yet every single one of them can be put into a complicated classification system through simple diagnosis.

This classification system has many layers, so you can move from a species to a family to a class to a kingdom. As a business, you have to find a way to classify the needs of your consumers to make that information more digestible. When you can do this, you're suddenly not trying to make a decision based on a million possibilities. You are classifying the challenges, and in doing so you're able to determine the ones that are irreversible from the ones that can be changed through a similar classification framework.

Having this clarity reduces the risk of making the wrong decision because you better understand the challenge and you know the solution you are working towards. You have a defined direction of travel.

Of course, having a defined direction of travel can reduce your room to manoeuvre, and this is particularly the case when you carve out a niche in a very specific area. The challenge in this instance is how do you diversify and change your trajectory without unwinding much of what you've already done? The key lies in this classification system.

How do classification systems aid decision making?

The classification system you have at your business will empower (or if you get it wrong, disempower) people to deal with your customers in an intelligent way. To illustrate how this works, we're going to look at how a stealth bomber manages to stay in the air because according to the laws of aviation, it shouldn't.

We've even heard these planes described as having the aerodynamics of a shoe being thrown across the room. So, how do they stay in the air? The answer is the computer systems that carry out a multitude of micro adjustments every second. The pilot of a stealth bomber therefore doesn't actually fly the plane because a human isn't capable of responding to that number of decisions so quickly.

The pilot is still steering the plane and managing the weapons and communications systems, but if that plane gets into trouble then it ejects the pilot to preserve his or her life and self-destructs to protect its secrets from falling into enemy hands.

Working in a customer-facing role these days is a lot like piloting a stealth bomber, except you aren't in a position to eject and self-destruct if you get into trouble. Every customer interaction could lead to myriad situations and that means people are faced with making myriad decisions every day.

If there aren't enough, or the right, systems in place to empower the people in those customer-facing roles to make the right decisions, they're trapped in a restrictive process, much like a pilot would be in a stealth bomber if they didn't have the option of ejecting. Having a classification system can help your employees in customer-facing roles to digest and distill the millions of options in terms of how they could react and guide them towards a response that meets a particular customer's need.

This is moving towards augmented intelligence, where a business uses machine learning to provide insights to its team, which can then make informed decisions to deliver better services to customers.

When we're dealing with people, we have to respond in an emotionally intelligent way. Having a clearly defined classification system within your business allows your customer-facing people to do just that.

Although the leader of an organisation won't necessarily be involved in creating these classification systems, they will set the principles that overlay the classification hierarchy. These principles will encompass what the company thinks about its customers as well as what it does and doesn't want to do for its customers. A business' principles have to be deeply embedded within its DNA so that everyone who works for that company understands them and can act on them.

Now compare that to another experience Az had where the principle to make the customer happy was not nearly as deeply ingrained as the principle to make the business money or save time and costs.

It is also why it's so important to clearly define your brand values and then use them to drive every interaction with a customer. Don't jump to conclusions about what the answer is, instead you start with identifying your problem and work to find the right solution to solve it.

The Moment Builder

To effectively provide an experience, we've discussed that you need to be able to adapt at speed. The actions that you take are underpinned by everyone in the organisation making the right decisions that make a difference to your customer at the right time. This means that you need to shift from curating experiences and waiting for the right time to deliver them, to having a system through which to curate an appropriate response to any moment. Curating moments will give brands the opportunity to better respond to their customers' needs and build meaningful experiences as a result. To do this requires a classification system.

A system is made up of a hierarchy of layers, which can evaluate any customer moment to produce the right response, even if it's just a one-of-a-kind situation.

These layers can be multifaceted and very complex, and what we have illustrated in the preceding diagram is a simple representation of what this might look like in our Moment Builder. Let's step through it and see how it is used to understand moments that matter to your customer.

Each step seeks to understand the context of whatever moment is in question and quickly curate an appropriate response.

In this version of the Moment Builder, the first step would establish if the moment is initiated by your brand or your customer. This first step is important because there may be a material difference when responding to a proactive brand intervention versus an incoming customer engagement.

Now you can add the level of emotional intensity that might be experienced by the customer as a result of this interaction (step two). This allows you to lay out the degree of empathy that may be required to deal with this interaction in the most meaningful way possible, which in turn affects your response.

You can then step into level three, urgency. Here you can assess how real-time the need of this customer is. In other words, is there a time-dependent need? If it is a highly emotive, inbound interaction, based on a time-based need, the nature of the response, the level of empathy, and the timing of it will be fundamentally different to a non-emotive, non-time-dependent moment.

For example, a car rental company responding to a phone call of a customer who has broken down in one of its vehicles is going to elicit a very different level of response compared to an email from a potential customer.

These types of (illustrative) dimensions begin to underpin what you know about the state of this given moment.

The last two layers in this example then start to define how you curate an appropriate experience for that moment, using what you know about your customers, what they value, what they care about, and their experience with the brand. These are human-centric insights that you can use to contextually frame the right response. For example:

- What values does the brand want to be known for? Do you want to be seen as caring, sustainable, customer-first, or honest, for example?

- What do you think your customer values? What do you think or know that your customer cares about? Convenience, price, or loyalty, for instance?

- What state do you think your customer is in? What need do you think your customer is trying to satisfy and how can you use what you think you know about this customer to shape how you personalise that moment for him or her?

- What is the value of the customer to you? There are some customers who bring more value to a business than others. In some cases, it may be that you as a brand need to step away from a particular customer, but you have to consider how to do this in a sensitive way, especially if one of the values you want to be known for is customer-first.

- What do you know about your customer? What information have you consolidated? What is your customer's motivation and do you understand his or her emotional state?

Each of these parameters can impact how you respond to a given moment. In terms of the preceding point 4, let's take an online footwear and clothing retailer as an example. There could be two customers who order 30 pairs of shoes each, so on the face of it they both look like valuable customers. However, customer A returns 29 of his 30 pairs of shoes, whereas customer B returns 5 of her orders. With this added perspective, customer B is a lot more valuable to the business than customer A.

This retailer might reach a point where it needs to politely decline customer A, and it would use its values as a parameter to do that in the most diplomatic way possible so that it doesn't damage the brand or the business and still maintains a memorable customer experience. This is also where EQ would come into play.

As a business, you have to set the variables and parameters that make up the framework of customer experiences. The experiences you offer customers need to be based on responses to those rules, which then also allows you to factor in those unbound interactions that you as a brand don't have control over.

A good analogy to demonstrate how introducing these rules helps your business comes from tennis. Think of the umpire in a tennis match as the brand, and the players as the customers. In the past, when a ball was hit close to the line, the umpire would have the final say on whether it was in or out. The players would often argue and there might be a debate on court, but ultimately what the umpire said stood and there was no definitive answer in those marginal calls.

In more recent years, Hawk-Eye has been introduced to the professional game and this has removed all the subjectivity over whether a shot is in or out of the court. In addition, there are rules relating to how often a player can use Hawk-Eye to challenge a call by a line judge or the umpire in order to prevent players from abusing the system.

In a business, these rules give everyone who works for you a definitive guide on how to deal with different situations, so customers will get the same level of experience regardless of who they are in contact with in your business. Introducing additional layers of rules (such as how often tennis players can use Hawk-Eye) enables the business to quantify the experience and use it to guide the response to customers.

These principles have to be considered alongside a customer's value, however. If we go back to tennis, John McEnroe was famous for his shouting matches with umpires over their decisions, and he might seem like the kind of difficult customer you want to manage out of your business. However, at the peak of his career, the sport would have lost more by letting him go than it would have gained.

Much like the example of a footwear and clothing retailer we gave earlier, it's important to look at the value a customer brings to your business and discern whether he or she is worth hanging on to or whether this customer needs to be managed out of your customer base in a sensitive way.

Do you remember the example Rich shared earlier about his experiences with the razor and shaving company Harry's? This was one step up from the fresh meal subscription in that the customer service rep at Harry's not only refunded the money immediately, but provided that human engagement that made the customer (in this case Rich) feel valued.

Another similar example came our way through a colleague, who placed an order with Beauty Kitchen, a sustainable and natural beauty products company. She ordered one of its sample sets to try out the products in its range before committing to buying larger pots of its products. When the sample set arrived, one of the samples was missing.

She emailed Beauty Kitchen and received a reply the same day apologising and promising to post the missing item immediately. Two days later, she received the missing product, along with some free samples and a voucher for 10% off her next purchase. Two years later, she tells us she is still ordering from the company because it responded with EQ to the issue she had with her first order.

Every sale matters

We have talked a lot about businesses that rely on repeat custom, but what about if purchases are more likely to be one-off transactions? In this case, it's even more important to get everything right because if you're just making one sale and having that one series of interactions with a customer, a bad experience really stands out. By contrast, if someone makes 300 purchases from you and only one of those goes wrong, the bad experience is offset by all the good ones.

Kat, a friend of ours, shared a good example of how to get this right recently. Around her birthday, her sister-in-law told her to expect a delivery by 1 p.m. the following day. Kat didn't know this, but it was a box of cupcakes. She stayed in all morning and by about 2 p.m. nothing had arrived, so she sent her sister-in-law a text just to let her know.

Her sister-in-law had received a notification that the order had been delivered, so she got in touch with the company to ask what had happened. The company immediately apologised and said it would send a new box of cupcakes for delivery the following day.

The second box of cupcakes arrived to Kat as promised, and it was all sorted. But this isn't where the story ends. A couple of days later, Kat's sister-in-law received an email from the cupcake company. It explained that, after she had contacted them about the missing cupcakes, the company received an email from a woman who said, “I think you delivered some cupcakes to me by mistake. I'm really sorry because I ate them but I felt guilty because I have no idea who Kat is and I thought you should know.”

Even though the company solved the problem of the missing order quickly, it still had the EQ to realise that Kat and her sister-in-law might like to know what happened and why the cupcakes hadn't arrived. The company made it personal, which makes the customer feel valued and shows a human touch that is often missing when the blanket response to any issue is simply to provide a refund.

Making transactions personal isn't the only way to make customers feel valued when they are making a one-off purchase with you. How your business responds to any issues is just as important, even if they aren't your fault. Applying EQ in such situations can help you deliver an exceptional customer experience. It all comes back to thinking about what customers need in a given scenario and working out how best to deliver that for them and your business.

From automation to augmented intelligence

The number of touchpoints between a business and its customers has increased significantly, while the range of technology to help organisations manage those customer interactions has also expanded and developed. As a result, businesses are seeking ways to make their interactions with customers smoother and more efficient, which is why automation is such a hot topic.

This technology undoubtedly has a place in the modern customer experience environment; however, it's essential that EQ is considered alongside automation, otherwise it can have the opposite outcome to the one you are intending.

We see many businesses turning to automation as one of their strategies to help solve problems along the customer journey and to try to improve the customer experience. However, it doesn't always work because it lacks that all-important component of EQ.

What businesses need to move towards is more augmented intelligence rather than automation alone. This involves interlacing the human element into automation to ensure that EQ is applied when it's required to not only provide a better customer experience, but to ensure that you don't inadvertently provide a poor customer experience as a result of your automations.

This example also comes back to the disconnection between departments that we discussed in Chapter 2. It is particularly common in larger, legacy businesses like banks. Each department isn't considering the whole customer experience, it is only considering the part of the experience that it is responsible for (and sometimes not even doing that very well).

When a business starts to automate, and to do so at scale, it has to put classification systems in place for those automations to work. However, as we have explained, you can't automate for every situation and every customer. A one-size-fits-all approach doesn't work.

What we are seeing emerge is the need for a framework, based around your brand values, that allows for flexibility in how every person in your business deals with customers. In having this framework, you're encouraging each person within your business to ask: “What am I trying to say to this customer? What do they mean to me? What are my values?” And then each person applies the answers to those questions in a way that aligns with your brand values.

The point with this is that every message that reaches a customer will have gone through the same system, the same framework, to ensure it aligns with those brand values and that it brings value to the customer, whether it comes from the marketing department, the finance department, the sales department, or the customer service department, any interaction with the customer will echo those brand values.

Although small businesses typically have fewer silos than large organisations, they can still fall into the trap of taking a blanket approach with their automations. Even if small businesses are able to avoid this initially, once they reach a certain critical mass the same problem is likely to appear. If you don't set out these frameworks as a foundation, at some point any business will run into the challenge of automating and scaling this.

Small businesses should consider these pitfalls in the early stages of their development because having this framework and rules in place will make it easier for them to send more tailored communications and have personal interactions with their customers not only now, but also as they grow.

Look at Amazon; it doesn't care about what particular type of customer you are when you make a complaint. It simply refunds because its core brand value is “happy customers.”

It's never just one dimension

Automation is just one strategy that businesses can use, just as segmentation is a subset of one of the main dimensions each business needs to consider to deliver NBX. Think back to the example we shared at the beginning of this chapter about the three-dimensional chess game in Star Trek. When you are playing in three dimensions, traditional moves aren't as relevant and you need to consider the board and game from multiple angles. You can't afford to only take a top-down view or you risk missing important facts and information that will inform and improve your strategies.

In a similar way, for every customer interaction, businesses need to consider:

- What do we know about you? This helps curate the message specifically for that customer.

- What do you value? What the customer values in a brand further tailors this message.

- What is your need? We have to know what each customer needs to ensure what we're offering is relevant.

- What is the urgency of your need? This is particularly important because in some circumstances urgency will be the highest priority. If you're stuck at the side of the road trying to find out whether your insurance policy gives you breakdown coverage, the urgency of that situation is significantly greater than what segment you fall into.

- What part of the situation drives the emotion? Will the solution you're offering the customer calm their emotion? Think back to the meal subscription service example Rich shared earlier; if someone is trying to cook dinner one evening and he doesn't have all the ingredients he needs, being given some money back might be nice, but it's unlikely to calm his emotion.

Many businesses dive straight into finding a solution, which comes back to the concept of outputs versus outcomes. There's a physical deliverable from an automation programme (output), at the end of the segmentation process you are left with a segmentation model (output).

If you haven't taken the time to think about your brand values and prioritise which you need to implement and how you need to execute them, you will keep coming up with outputs rather than outcomes. It's outcomes that deliver business value.

It can also lead to a misplaced focus because sometimes the solution isn't always what you immediately think it will be.

The solution to that problem wasn't as simple as the school initially thought, in terms of putting up a sign just telling people not to leave their rubbish there. By providing a sign explaining where the dump is, they gave people clear direction and steered them to the NBA.

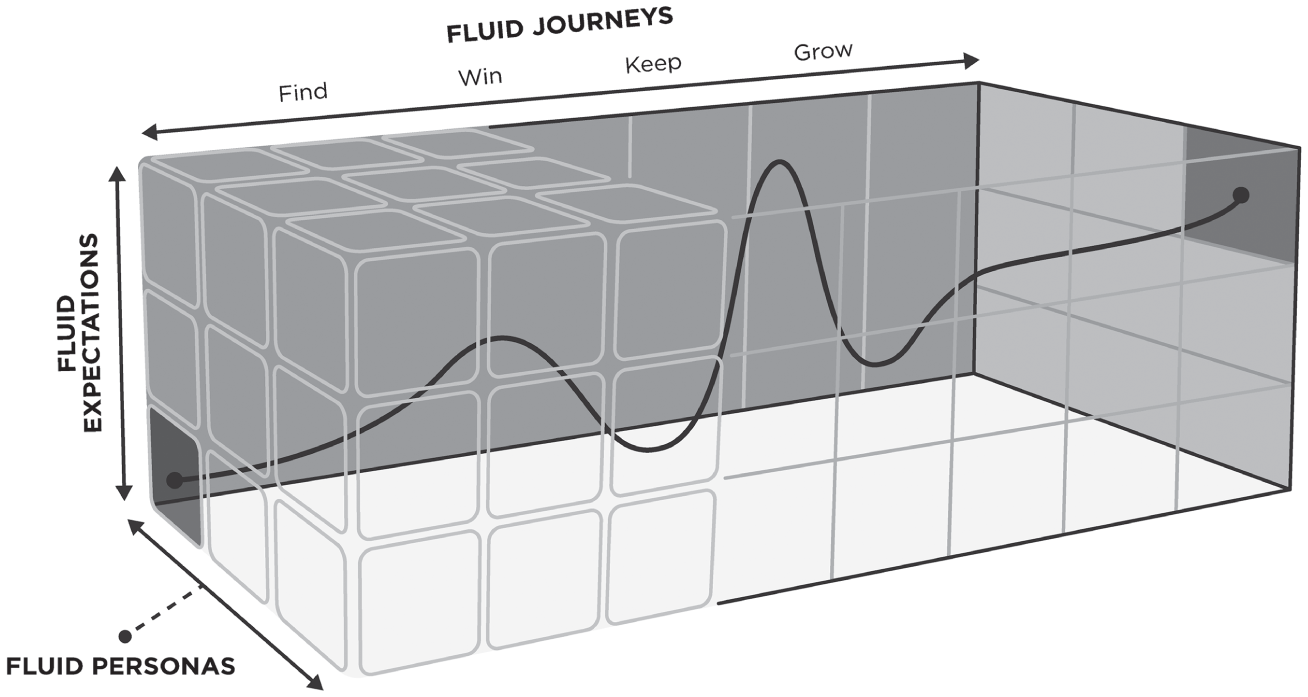

The Fluid Cube

If experience is the next battleground, businesses need to think carefully about how they can deliver the best possible experience for their customers.

Consumers are not just one dimensional, and as a brand it's important to consider the many dimensions of each consumer and to be aware that those dimensions can change during an interaction. To help explain this concept, we've come up with the Fluid Cube.

Picture a Rubik's cube and imagine that this is the consumer. The various combinations and permutations you can arrive at when you mix that cube represent the consumer at any given moment in time. There are three different dimensions in terms of the fluidity in which consumers behave.

Fluid personas

People can move between personas or, in fact, be multiple personas at once. This means the traditional concept of personas and segmentation is often outdated. For example, Az and his son both play ice hockey. When he's shopping for gear for his son, he's looking for products that are going to protect him on the ice. The focus is on safety and health. When Az is shopping for gear for himself, he's looking for the glossy, shiny, sexy gear that's going to make him look good when he steps out onto the ice. He's still the same person, but the context changes.

Fluid journeys

This is about understanding the triggers that will let you know what the intent is for an individual customer. For example, if you look at a motoring website, how does that brand know whether you're looking for a second car or you want to book a service for your current car? Sometimes businesses can make the wrong assumptions about a customer's intent and that sends them down the wrong route.

If we go back to the motoring website, most of those businesses know that using a car configurator is one of the highest converters for booking a test drive (at least it was pre-COVID). As a result, most of those websites will push you towards their car configurator, but that doesn't account for an existing customer whose intent is to book a service. This could see that customer being pushed down the wrong route on the website.

Just like with personas, a customer can flip between journeys at any given moment in time and brands have to consider how they can start to mix that accordingly.

Fluid expectations

This involves thinking about each customer's expectations and intent, as well as their state of happiness. Think about the difference between NBO, NBA, and NBX. If a customer isn't happy with the service currently being offered, don't try to sell something else. Instead think about what the NBA is for the right level of service or experience that the customer should have next. In some cases, that might be nothing at all, such as a cooling off period.

The point is you have to account for whatever that next action is in some shape or form, instead of just trying to sell. Factor in the level of emotion and the emotional state of each customer in comparison to all the other dimensions as well and remember that this is a fluid process. Each customer will always be shifting and changing. This is why we developed the Moment Builder. You can't pre-create every combination of the fluid cube because it's fluid. You have to curate the experiences in the moment.

Highlights

As we noted at the beginning of this chapter, doing something isn't the same as doing the right thing. All three of the chapters in the Principal part of this book are fundamentally about alignment, and ensuring that every piece of your brand and business is moving in the same direction, that you're all part of the same metaphorical race and share a common purpose.

Establishing a culture that is open to change is a key component in your work to become an adaptive organisation. As we move into the next part of the book, Crew, we're going to focus on autonomy and making sure that everyone in your organisation is empowered to be able to do the right thing. This is about creating a culture that enables change, ensuring that your organisation is not getting in the way of your opportunities.

We've started to touch on this topic already with discussions around frameworks that enable people to act with EQ and make decisions that meet the customer's need while aligning with the brand's values.

Let's come back to our Formula 1 team principal. They will start any race weekend by setting a clear vision for the team so that all know exactly what they are aiming for. The principal is making sure that everyone's focus is in the right place and that this is the right thing to be doing. And the principal will evolve their strategy over the course of a race weekend as it progresses to make sure that the team is still doing the right thing and making the right calls.

Then the principal will oversee what is happening with their car, their team, and their competitors to inform and evolve their strategy. Measuring the right metrics allows them to make alterations in the right places, and this is what gives them the edge.

Finally, the principal knows that there are many variables that can affect the outcome on race day, not all of these will be within their control and they aren't necessarily going to be available to make every tiny decision that's required to progress towards that vision. The principal will introduce processes and frameworks that every member of their team can work within to give them the greatest chance of success.

In Formula 1, this is complex enough; in the world of modern business, there are infinitely more variables and moving parts.

Understanding the complexity of the modern business environment is key. If you try to do everything at once, you won't progress. You have to make sure you are really good at one thing and if you focus on excelling in that area, you will see progress.

The key is working on your strengths as well as your weaknesses. Look at the difference in the quality of tennis players between the UK and the US in the 1990s. Each country took a very different approach to player development, and it was clear which produced a higher volume of top-ranked players. In the UK, players with a strong forehand but a weak backhand would be encouraged to focus on their weaker shot and bring it up to the same level as their strongest shot.

In the US, players would focus on making their strongest shot even stronger. In doing so, US players were able to excel far beyond their competitors. This brings us full circle to the peppered moth. When an evolution works, focus on what's working. Adapt or die, but if you adapt from a place of strength, you put yourself on a much stronger footing to not only survive, but to potentially thrive.

Regardless of how well you performed last year, without constant measuring, refining, and adapting, keeping up in a rapidly changing world is going to be an impossible task. The Formula 1 team principal understands this and inspires his crew members to improve their chance of success year after year.

The same applies to the world of business too if we are prepared to understand the need for change, can define measures that track our progress, and pivot according to the fluid movement of the marketplace.